Georges Kopp

Georges Kopp, the son of Alexander Kopp and Henrietta Neuman, was born in St Petersburg in 1902. The family fled to Switzerland on the outbreak of the Russian Revolution. Later they moved to Belgium where Kopp developed socialist views.

Kopp became an officer in the Belgian Army. On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Kopp travelled to Spain. Over the next few months he developed strong links with the Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), an organisation established by Andres Nin and Joaquin Maurin. This revolutionary anti-Stalinist Communist party was strongly influenced by the political ideas of Leon Trotsky.

As Kopp had military experience he was appointed as commander of the POUM section of the International Brigades. Kopp arrived on the Aragón Front in 1936. Other members of the group included George Orwell, Bob Edwards and Bob Smillie. Kopp later commented: "We have had a complete success, which is largely due to the courage and discipline of the English comrades who were in charge of assaulting the principal of the enemy's parapets. Among them I feel it my duty to give a particular mention to the splendid actions of Eric Blair (George Orwell), Bob Smillie and Paddy Donovon."

At the end of April 1937 the Independent Labour Party contingent travelled to Barcelona for a period of leave. Bob Smillie was then given a permission document from a POUM official allowing him to go to a International Bureau meeting in Paris and a speaking tour of Scotland. When he got to Figueras he was arrested by police under the control of the Spanish Communist Party (PCE).

David Murray, the Independent Labour Party representative in Spain, later recalled: "Unfortunately, young Smillie was arrested at the exact time of the crisis in the Valencia government, and no definite steps could be taken to have him released during the period of flux." As Daniel Gray, the author of Homage to Caledonia (2008), has pointed out: "It was clear that Smillie had become a victim of the government's POUM clampdown."

Bob Smillie was charged with carrying "materials of war" (two discharged grenades intended as war souvenirs). He was taken to a prison in Valencia where he talked himself into a further, more serious charge of "rebellion against the authorities". POUM lobbied for the release of Smillie. The authorities in Valencia refused to release Smillie. On 4th June 1937 Smillie began complaining of stomach pains. He was eventually diagnosed with appendicitis. He was taken to hospital but was not operated on because of "ward congestion". On 12th June he was finally examined by a doctor, who came to the conclusion that "owing to congestion in his lower abdomen, he could not be operated upon". Smillie died later that day from peritonitis.

Georges Kopp wrote to Smillie's parents when he heard the news: "He (Bob Smillie) was one of the most gallant soldiers in the regiment which I commanded. It is a duty and a privilege to express to you my sympathy, and to assure you that Bob always carried himself bravely and courageously in and out of the firing line. You can be proud of him." Kopp later argued that Smillie had been murdered: "The doctor states that Bob Smillie had the skin and the flesh of his skin perforated by a powerful kick delivered by a foot shod in the nailed boot; the intestines were partly hanging outside. Another blow had severed the left side connection between the jaw and the skull and the former was merely hanging on the right side. Bob died about 30 minutes after reaching the hospital."

On 6th May death squads assassinated a number of prominent anarchists in their homes. The following day over 6,000 Assault Guards arrived from Valencia and gradually took control of Barcelona. It is estimated that about 400 people were killed during what became known as the May Riots. During this crackdown Ethel MacDonald assisted the escape of anarchists wanted by the Communist secret police. As a result she became known as the "Scots Scarlet Pimpernel".

On 16th June 1937 POUM was outlawed. Kopp was one of those arrested. George Orwell visited him in prison: " Kopp elbowed his way through the crowd to meet us. His plump flesh-coloured face looked much as usual, and in that filthy place he had kept his uniform neat and had even contrived to shave.... It is a terrible thing to see your friend in jail and to know yourself impotent to help him. For there was nothing that one could do; useless even to appeal to the Belgian authorities, for Kopp had broken the law of his own country by coming here.... Kopp was telling us about the friends he had made among the other prisoners, about the guards, some of whom were good fellows, but some of whom abused and beat the more timid prisoners, and about the food, which was pig-wash. Fortunately we had thought to bring a packet of food, also cigarettes."

Kopp was interrogated by NKVD agents but was released after being kept in prison for 18 months and in 1939 managed to reach England, where he went to live with Orwell's relatives, Laurence and Gwen O'Shaughnessy.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Kopp went to France and volunteered for the French Foreign Legion. In June 1940 he was wounded and captured by the German Army. However, after a spell in a military hospital he escaped and lived in Marseilles. It was not long before he was working for British naval intelligence.

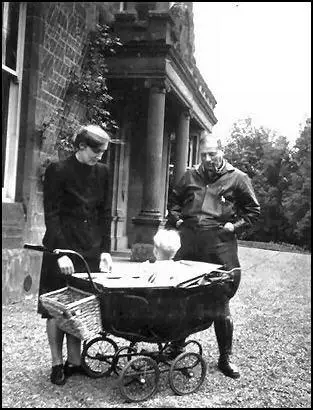

In September 1943 Kopp managed to get back to London. Soon afterwards he married Doreen Hunton, the younger sister of Gwen O'Shaughnessy. They moved to Scotland but in 1949 they settled in Whaley Bridge, Derbyshire.

Georges Kopp died in Marseilles on 15th July 1951.

Primary Sources

(1) Don Bateman, Georges Kopp and the POUM Militia (undated)

Spain was a gigantic melting pot at a time when Socialists were being hounded out of their own countries by Fascist and near-Fascist regimes. Stateless men went to Spain in the hope of adding their own twopennyworth to the anti-Fascist struggle, but their own political ideology was often undeveloped. It matured under Fascist and Stalinist repression.

One such character was Georges Kopp, a Belgian Socialist born in 1902. He was too young for service during the First World War but had lived under the German occupation. His track record included service as an officer in the Belgian army, as a volunteer officer in the POUM militia, as a member of the French army and French Resistance, and as a field operator for British Intelligence before taking up postwar residence in Scotland. He died when still a comparatively young man. His service is unrecorded. Hugh Thomas, in his standard work on the Civil War, like most similar books, does not even mention him.

Kopp was somewhat unusual inasmuch as he was a professionally qualified engineer, and very few left wingers have come from these ranks. He was a committed Socialist with some military experience from his conscription period. He had been commissioned and was still a member of the Officer Reserve. At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War he helped to organise the buying of arms and gun-running for the Republic in Western Europe. He also formed a small engineering firm producing cartridges and bullets which were shipped out to Spain. Complementing this he bought the ingredients for explosives and exported them so that live ammunition could then be manufactured in Spain itself. Once the Non-Intervention agreement was signed this became illegal, and the western powers became gamekeepers for Franco, who got all the arms he needed, to start with from Mussolini and later from Hitler. It did not take the intelligence services long to trace arms supplies back to Kopp, and the Belgian government began nosing around his blockade busting activities. He then realised that his usefulness in that field was over. He left in a hurry for Spain, arrived in Barcelona and volunteered for the POUM militia.

(2) George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (1938)

My wife and I visited Kopp that afternoon. You were allowed to visit prisoners who were not incommunicado, though it was not safe to do so more than once or twice. The police watched the people who came and went, and if you visited the jails too often you stamped yourself as a friend of "Trotskyists" and probably ended in jail yourself. This had already happened to a number of people.

Kopp was not incommunicado and we got a permit to see him without difficulty. As they led us through the steel doors into the jail, a Spanish militiaman whom I had known at the front was being led out between two Civil Guards. His eye met mine; again the ghostly wink. And the first person we saw inside was an American militiaman who had left for home a few days earlier; his papers were in good order, but they had arrested him at the frontier all the same, probably because he was still wearing corduroy breeches and was therefore identifiable as a militiaman. We walked past one another as though we had been total strangers. That was dreadful. I had known him for months, had shared a dug-out with him, he had helped to carry me down the line when I was wounded; but it was the only thing one could do. The blue-clad guards were snooping everywhere. It would be fatal to recognize too many people.

The so-called jail was really the ground floor of a shop. Into two rooms each measuring about twenty feet square, close on a hundred people were penned. The place had the real eighteenth-century Newgate Calendar appearance, with its frowsy dirt, its huddle of human bodies, its lack of furniture - just the bare stone floor, one bench and a few ragged blankets - and its murky light, for the corrugated steel shutters had been drawn over the windows. On the grim walls revolutionary slogans -"Visca P.O.U.M.!" "'Viva la Revolution" and so forth - had been scrawled. The place had been used as a dump for political prisoners for months past. There was a deafening racket of voices. 'This was the visiting hour, and the place was so packed with people that it was difficult to move. Nearly all of them were of the poorest of the working-class population. You saw women undoing pitiful packets of food which they had brought for then, imprisoned men-folk. There were several of the wounded men from the Sanatorium Maurin among the prisoners. Two of them had amputated legs; one of them had been brought to prison without his crutch and was hopping about on one foot. There was also a boy of not more than twelve; they were even arresting children, apparently. The place had the beastly stench that you always get when crowds of people are penned together without proper sanitary arrangements.

Kopp elbowed his way through the crowd to meet us. His plump flesh-coloured face looked much as usual, and in that filthy place he had kept his uniform neat and had even contrived to shave. There was another officer in the uniform of the Popular Army among the prisoners. He and Kopp saluted as they struggled past one another; the gesture was pathetic, somehow. Kopp seemed in excellent spirits. "Well, I suppose we shall all be shot," he said cheerfully. The word "shot" gave me a sort of inward shudder. A bullet had entered my own body recently and the feeling of it was fresh in my memory; it is not nice to think of that happening to anyone you know well. At that time I took it for granted that all the principal people in the P.O.U.M., and Kopp among them, would be shot. The first rumour of Nin's death had just filtered through, and we knew that the P.O.U.M. were being accused of treachery and espionage.

Everything pointed to a huge frame-up trial followed by a massacre of leading "Trotskyists". It is a terrible thing to see your friend in jail and to know yourself impotent to help him. For there was nothing that one could do; useless even to appeal to the Belgian authorities, for Kopp had broken the law of his own country by coming here. I had to leave most of the talking to my wife; with my squeaking voice I could not make myself heard in the din. Kopp was telling us about the friends he had made among the other prisoners, about the guards, some of whom were good fellows, but some of whom abused and beat the more timid prisoners, and about the food, which was "pig-wash". Fortunately we had thought to bring a packet of food, also cigarettes.