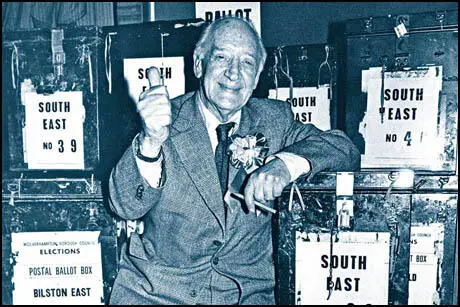

Bob Edwards

Robert (Bob) Edwards, the son of a docker, was born in Liverpool on 16th January 1906. He was educated at local schools and as a young man joined the Guild of Youth, an organisation founded by the Independent Labour Party. He was a member of the delegation that visited the Soviet Union that met Joseph Stalin, Vyacheslav Molotov and Leon Trotsky.

In 1932 he was elected to the Liverpool City Council. Two years later he helped organize the Lancashire Hunger Marchers. He remained in the ILP and in 1935 he unsuccessfully contested Chorley.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Edwards asked members of the Independent Labour Party to volunteer to join the International Brigades. Stafford Cottman was one of the men who offered his services: "I was asked to go along to their headquarters and I met Bob Edwards was its leader.... At headquarters we were all interviewed by Bob and a couple of others. They asked you simple things like why you wanted to go to Spain. The idea was to find out whether you did have a sort of principle or whether it was pure adventure."

Edwards arrived on the Aragón Front in 1936. Other members of the group included George Orwell and Bob Smillie. These men served alongside POUM forces and its leader, Georges Kopp later commented: "We have had a complete success, which is largely due to the courage and discipline of the English comrades who were in charge of assaulting the principal of the enemy's parapets."

Edwards was appointed as a captain in the battalion. He later recalled: "We spent much of our time training members of the Spanish Militia how to take cover and we were constantly trying to persuade them that to walk upright and bravely into an offensive was not necessarily the best method." He added: "The Spanish Civil War, if properly supported, would have been the first defeat of fascism and we very nearly won that war. In the early months of the war, we were winning easily. We attacked Saragossa and could have taken it, but we had a shortage of ammunition and supplies. We released prisoners from the heart of the town. We had the men but not the equipment, and that was true throughout the whole of the war."

Edwards served with Bob Smillie on the front. "His lilting Scottish melodies could often be heard enlivening many difficult and monotonous hours. I can hear his voice now as he shouted slogans in Spanish from our trenches in the Aragon mountains across to the enemy lines. Was it merely coincidence that at this period 100 Spanish workers deserted from Franco?"

According to Gordon Brown: "Bob Edwards was acting as an intermediary for the Spanish Government and managed to negotiate a deal with a British shipowner to arrange the shipment of food supplies. Edwards bought the boat, promising that the Spanish Government would pay up when it reached France."

At the end of April 1937 the Independent Labour Party contingent travelled to Barcelona for a period of leave. Bob Smillie was then given a permission document from a POUM official allowing him to go to a International Bureau meeting in Paris and a speaking tour of Scotland. When he got to Figueras he was arrested by police under the control of the Spanish Communist Party (PCE).

David Murray, the Independent Labour Party representative in Spain, later recalled: "Unfortunately, young Smillie was arrested at the exact time of the crisis in the Valencia government, and no definite steps could be taken to have him released during the period of flux." As Daniel Gray, the author of Homage to Caledonia (2008), has pointed out: "It was clear that Smillie had become a victim of the government's POUM clampdown." ob Smillie was charged with carrying "materials of war" (two discharged grenades intended as war souvenirs). He was taken to a prison in Valencia where he talked himself into a further, more serious charge of "rebellion against the authorities". POUM lobbied for the release of Smillie. So did Bob Edwards, James Maxton, Fenner Brockway, and other leaders of the Independent Labour Party.

The authorities in Valencia refused to release Smillie. On 4th June 1937 Smillie began complaining of stomach pains. He was eventually diagnosed with appendicitis. He was taken to hospital but was not operated on because of "ward congestion". On 12th June he was finally examined by a doctor, who came to the conclusion that "owing to congestion in his lower abdomen, he could not be operated upon". Bob Smillie died later that day from peritonitis.

Bob Edwards returned to England in 1938. He later recalled: "I saw enough blood in the Spanish Civil War to last me all my life. Millions died in three years... Returning to England, I thought a world war was inevitable. In 1939 I went to America to help the trade union movement... I came back to England because I could see war was coming. I linked up again with the Chemical Workers Union. I wasn't eligible to be called up because I had been an officer in a foreign army. They wouldn't have had me.''

In 1943 Edwards became National Chairman of the Independent Labour Party. In the 1945 he was defeated by Ronald Bell, the Conservative Party candidate, in the Newport by-election. After the publication of Chemicals: Servant or Master? he was elected as the General Secretary of the Chemical Workers Union in 1947.

Edwards became the Labour Party candidate for Bilston and won the seat in the 1955 General Election. In 1961 Edwards published A Study of a Master Spy, a book about Allen Dulles.

He was appointed as leader of Parliamentary Delegation North Atlantic Assembly 1968-70. In 1974 he became the MP for Wolverhampton South East. In 1983 he became the oldest member sitting in the House of Commons.

Bob Edwards, who stood down in 1987, died on 4th June, 1990.

Primary Sources

(1) Bob Edwards, Heroic Voices of the Spanish Civil War (2009)

The Spanish Civil War, if properly supported, would have been the first defeat of fascism and we very nearly won that war. In the early months of the war, we were winning easily. We attacked Saragossa and could have taken it, but we had a shortage of ammunition and supplies. We released prisoners from the heart of the town. We had the men but not the equipment, and that was true throughout the whole of the war.

The governments of the West concocted the principle of non-intervention, which Germany and Italy signed up to but then ignored. There were 70,000 Germans and 55,000 Italians fighting in Spain. Up in Aragon we were not fighting Spaniards; we were fighting Moors, Italians and Germans.

I saw enough blood in the Spanish Civil War to last me all my life. Millions died in three years. I went back to Spain in 1959 and was arrested by the secret police. It's a long story, but afterwards when I went back to the hotel the staff lined up to welcome me. They had photographs and asked me if I recognized any of those who had fought in Aragon. Half of the staff had relatives who had died in the Spanish Civil War.

Overwhelming masses of Spanish [people] were supporting us. The Spanish Civil War was a social revolution: no black market, prostitution was abolished, no bullfighting, the workers were put in control of factories and large estates were formed into collectives. But then they decided to halt the social revolution and concentrate on military means. We could not have won militarily but we could have won the social revolution. George Orwell came to the same conclusion.

Orwell was tall, quiet, suffered from bronchitis and developed TB. He suffered in the mountains where it was bitterly cold. He was very courageous. In one incident, I remember, he had been training Spaniards. We were being attacked and he was with a machine gun. The gun overheated and couldn't be used so the Spanish crew stood up, waiting to die. He stood up with them. I said, `Lay down you bloody fools'. He had such feeling for the Spaniards. We did have problems convincing them to take cover, though. Sometimes the war was a comic opera. We had no maps. I said you can't fight a war without maps.

Returning to England, I thought a world war was inevitable. In 1939 I went to America to help the trade union movement. We had withdrawn the International Brigades by then. None of the Germans or Italians (fascists) withdrew. I came back to England because I could see war was coming. I linked up again with the Chemical Workers Union. I wasn't eligible to be called up because I had been an officer in a foreign army. They wouldn't have had me.

(2) Gordon Brown, Maxton (1986)

From September 1936 a steady stream of British volunteers travelled in small groups over the Pyrenees into Spain. Bob Edwards was captain of the ILP contingent. During the first months of 1937, they did a twelve-week stint on the Aragon Front, taking part in the capture of Mount Aragon and Saragossa. "We spent much of our time training members of the Spanish Militia how to take cover and we were constantly trying to persuade them that to walk upright and bravely into an offensive was not necessarily the best method," Edwards recalled later.

Edwards was joined in his contingent by George Orwell, who had by then applied to join the ILP. Orwell too had been a pacifist and according to Bob Edwards, had, during 1935, submitted a manuscript on pacifism which was "long and absolutist in character" for the consideration of the ILP. The two met again in December 1936 on the Aragon Front during the Civil War. Homage to Catalonia, Orwell's best selling account of the Spanish Civil War, was to follow.

As ILP members fought alongside the Republicans, Maxton stepped up his propaganda effort on the Spanish people's behalf. Writing in January 1937, Maxton argued that the overt intervention of Germany and Italy required a British response. Five months ago, he wrote, it might have been argued that it did not matter to Great Britain which side won in Spain and that a policy of intervention was the one calculated to limit the extent of hostilities and to hasten the restoration of peace. Franco had practically unrestricted aid from the two Fascist powers, Germany and Italy, while Britain had done nothing to help the Republicans. Worse than that, the Government had in effect tacitly supported the Fascists. Their "class prejudices were with Franco".

Maxton followed this up with an assault on the Government in Parliament. Non-intervention had actually been an act of discrimination against the Spanish People's Government. If Spain had been ruled by a right-wing government, it would have been accorded all the rights normally accorded to foreign powers. Maxton's intervention in the debate dwarfed other contributions. The speech, the Guardian said, showed "perfection from the technical point of view. After this brilliant example of the art of debating the other speakers seemed to be amateurish."