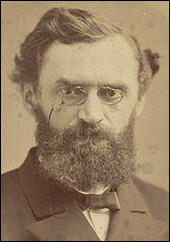

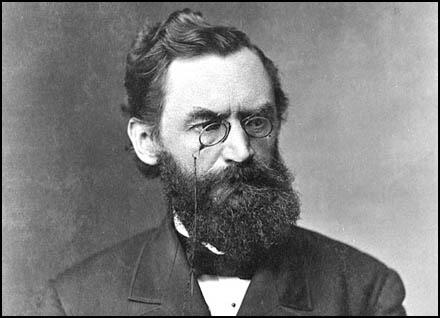

Carl Schurz

Carl Schurz was born in Cologne, Germany, on 2nd March, 1829. While studying at the University of Bonn he became involved in radical politics. Schurz took part in the 1848 German Revolution and was afterwards forced to flee to Switzerland.

Schurz spent time in France and England before emigrating to the United States in 1852. Schurz and his wife lived in New York for a while before buying a farm in Watertown, Wisconsin. In 1856 Margarethe Schurz founded the first kindergarten in America. A strong supporter of universal suffrage, Schurz once wrote: "Our ideals resemble the stars, which illuminate the night. No one will ever be able to touch them. But the men who, like the sailors on the ocean, take them for guides, will undoubtedly reach their goal."

A leading member of the Republican Party, in 1860 Schurz campaigned for Abraham Lincoln in Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. After the election, President Lincoln appointed Schurz as U.S. envoy to Spain.

Schurz was an active campaigner against slavery and on the outbreak of the American Civil War joined the forces of the Union Army. He helped recuit Germans living in New York before being asked to negotiate with European governments on behalf of Abraham Lincoln.

On his return to the United States, Schurz served under General John Fremont, the commander of the Department of the West. Soon afterwards he was given the rank of brigadier general and placed in command of the 3rd Division of the Army of Virginia (26th June, 1862 to 12th September, 1862).

Schurz also commanded the 3rd Division of the Army of Potomac (12th September, 1862 to 2nd April, 1863) and took part in the battles at Bull Run (July, 1862) and Fredericksburg (December, 1862). After the battle he was promoted to the rank of major general, replacing his friend and fellow German, Franz Sigel. Schurz also took part in the battle at Chancellorsville (May, 1863) and Gettysburg (July, 1863) before being given command of the 3rd Division of the Army of the Cumberland (25th September, 1863 to 21st January, 1864).

After the war Schurz worked as the Washington correspondent of the New York Tribune. This was followed by a period as editor-in-chief of the Detroit Post. In 1867 he became editor of the German language newspaper, the Westliche Post, in St. Louis, Missouri.

Schurz remained active in the Republican Party and in 1869 was elected to the Senate. In 1872 he, like many Radical Republicans, supported Horace Greeley against Ulysses S. Grant, the official Republican candidate. Despite the efforts of Schurz and his close friend in Missouri, Joseph Pulitzer, Grant won the presidential election by 286 electoral votes to 66.

In 1877 President Rutherford Hayes appointed Schurz as his secretary of the interior. Over the next four years Schurz introduced civil service reforms and made improvements to the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

After leaving office in 1881 Schurz returned to journalism and became managing editor of the New York Evening Post. He also wrote for Harper's Weekly, The Nation and had several books published including The Life of Henry Clay (1887) and Abraham Lincoln (1891). Carl Schurz died on 14th May, 1906.

Primary Sources

(1) Carl Schurz arrived in the United States in 1852. Soon afterwards he visited Washington. He described the city in his autobiography published in 1906.

My first impressions of the political capital of the great American Republic were rather dismal. Washington looked at that period like a big, sprawling village, consisting of scattered groups of houses which were overtopped by a few public buildings - the Capitol, only what is now the central part was occupied, as the two great wings in which the Senate and the House of Representatives now sit were still in the process of construction; the Treasury, the two wings of which were still lacking; the White House; and the Patent Office, which also harbored the Department of the Interior. The departments of State, of War, and of the Navy were quartered in small, very insignificant looking houses which might have been the dwelling of some well-to-do shopkeepers. There was not one solidly built-up street in the whole city - scarcely a block without gaps of dreary emptiness.

(2) Carl Schurz, speech to members of the Republican Party in Massachusetts (18th April, 1859)

I wish the words of the Declaration of Independence, "that all men are created free and equal, and are endowed with certain inalienable rights," were inscribed upon every gatepost within the limits of this republic. From this principle the revolutionary fathers derived their claim to independence; upon this they founded the institutions of this country; and the whole structure was to be the living incarnation of this idea.

Shall I point out to you the consequences of a deviation from this principle? Look at the slave states. This is a class of men who are deprived of their natural rights. But this is not the only deplorable feature of that peculiar organization of society. Equally deplorable is it that there is another class of men who keep the former in subjection. That there are slaves is bad; but almost worse is that there are masters.

Are not the masters freemen? No, sir! Where is their liberty of the press? Where is their liberty of speech? Where is the man among them who dares to advocate openly principles not in strict accordance with the ruling system? They speak of a republican form of government, they speak of democracy; but the despotic spirit of slavery and mastership combined pervades their whole political life like a liquid poison. They do not dare to be free lest the spirit of liberty become contagious.

The system of slavery has enslaved them all, master as well as slave. What is the cause of all this? It is that you cannot deny one class of society the full measure of their natural rights without imposing restraints upon your own liberty. If you want to be free, there is but one way - it is to guarantee an equally full measure of liberty to all your neighbors.

(3) On the outbreak of the American Civil War Carl Schurz asked Abraham Lincoln for permission to form a regiment in New York.

I promptly received the desired authority for raising the regiment, and departed for the City of New York. i found the people of New York in the full blaze of the patriotic emotions excited by the firing upon Fort Sumner and the President's call for volunteers. There were recruiting stations in all parts of the town. The formation of regiments proceeded rapidly. Wealthy merchants were vying with each other in lavish contributions of money for the fitting out of troops, and numberless women of all classes of society were busy stitching garments or bandages for the soldiers, or embroidering standards.

In New York, I found that many of the German cavalrymen I had counted upon had already enlisted in the infantry regiments then forming. But there were enough of them left to enable me to organize several companies in a very short time, and I should certainly have completed my regiment in season for the summer campaign, had I not been cut short in my work by another call from the government. I received a letter from the Secretary of State informing me that circumstances had rendered my departure for my place at Madrid eminently desirable, and that he wished me to report myself to him at Washington as soon as possible.

(4) Carl Schurz served as an officer under General John Fremont during the American Civil War.

I joined General Fremont's army at Harrisonburg, Virginia, on June 10th, 1862, and reported myself for duty. At the beginning of the Civil War I heard him spoken of in Washington as one of the coming heroes of the conflict, in most extravagant terms. I remember especially Mr. Montgomery Blair, the Postmaster General in Mr. Lincoln's administration, insisting that Mr. Fremont must at once be given large and important military command, and predicting that the genius and energy of this remarkable man would soon astonish the country. Fremont was, indeed, promptly made a major general in the regular army, and entrusted with the command of the Department of the West, including the State of Illinois and all the country from the Mississippi to the Rocky Mountains, with headquarters at St. Louis. But he sorely disappointed the sanguine expectations of his friends. He displayed no genius for organization. Fremont's headquarters seemed to have a marked attraction for rascally speculators of all sorts, and there was much scandal caused by the awarding of profitable contracts of persons of bad repute.

(5) Carl Schurz served under General Ambrose Burnside during the American Civil War. He wrote about the battle of Fredericksburg in December, 1862.

When McClellan at last had crossed the Potomac and Richmond, the President removed him from his command and put General Burnside in his place. The selection of Burnside for so great a responsibility was not a happy one. He was a very patriotic man whose heart was in his work, and his sincerity, frankness, and amiability of manner made everybody like him. But he was not a great general, and he felt, himself, that the task to which he had been assigned was too heavy for his shoulders. The complaint against McClellan having been his slowness to act. Burnside resolved to act at once. The plan of campaign he conceived was to cross the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg, and thence to operate upon Richmond.

The battle began on December 13th, 1862, soon after sunrise, under a gray wintry sky. Standing inactive in reserve, we eagerly listened to the booming of the guns, hoping that we should hear the main attack move forward. At eleven o'clock Burnside ordered the assault from Fredericksburg upon Marye's Heights, Lee's fortified position. Our men advanced with enthusiasm. A fearful fire of artillery and musketry greeted them. Now they would stop a moment, then plunger forward again.

Through our glasses we saw them fall by hundreds, and their bodies dot the ground. As they approached Lee's entrenched position, sheet after sheet of flame shot forth from the heights, tearing fearful gaps in our lines. There was no running back of our men. They would sometimes stop or recoil only a little distance, but then doggedly resume the advance. A column rushing forward with charged bayonets almost seemed to reach the enemy's ramparts, but then to melt away.

Here and there large numbers of our men, within easy range of the enemy's musketry, would suddenly drop like tall grass swept down with a scythe. They had thrown themselves upon the ground to let the leaden hail pass over them, and under it to advance, crawling. It was all in vain. The enemy's line was so well posted and protected by a canal and a sunken road and stone walls and entrenchments skillfully thrown up, and so well defended, that it could not be carried by a front assault.

The early coming of night was most welcome. A longer day would have been only a prolonged butchery. And we, of the reserve, stood there while daylight lasted, seeing it all, burning to go to the aid of our brave comrades, but knowing also that it would be useless. Hot tears of rage and of pitying sympathy ran down many a weather-beaten cheek. No more horrible and torturing spectacle could have been imagined.

General Burnside bore himself like an honorable man. During the battle he had proposed to put himself personally at the head of his old corps, the Ninth, and to lead it in the assault. Reluctantly he desisted, yielding to the earnest protests of his generals. After the defeat he unhesitatingly shouldered the whole responsibility for the disaster. He not only did not accuse the troops of any shortcomings, but in the highest terms he praised their courage and extreme gallantry. He blamed only himself.

(6) Carl Schurz served under General George Meade at the battle of Gettysburg in July, 1863.

To look after the wounded of my command, I visited the places where the surgeons were at work. At Bull Run, I had seen only a very small scale what I was now to behold. At Gettysburg the wounded - many thousands of them - were carried to the farmsteads behind our lines. The houses, the barns, the sheds, and the open barnyards were crowded with moaning and wailing human beings, and still an unceasing procession of stretchers and ambulances was coming in from all sides to augment the number of the sufferers.

A heavy rain set in during the day - the usual rain after a battle - and large numbers had to remain unprotected in the open, there being no room left under roof. I saw long rows of men lying under the eaves of the buildings, the water pouring down upon their bodies in streams.

Most of the operating tables were placed in the open where the light was best, some of them partially protected against the rain by tarpaulins or blankets stretched upon poles. There stood the surgeons, their sleeves rolled up to the elbows, their bare arms as well as their linen aprons smeared with blood, their knives not seldom held between their teeth, while they were helping a patient on or off the table, or had their hands otherwise occupied; around them pools of blood and amputated arms or legs in heaps, sometimes more than man-high.

Antiseptic methods were still unknown at that time. As a wounded man was lifted on the table, often shrieking with pain as the attendants handled him, the surgeon quickly examined the wound and resolved upon cutting off the injured limb. Some ether was administered and the body put in position in a moment. The surgeon snatched his knife from between his teeth, where it had been while his hands were busy, wiped it rapidly once or twice across his blood-stained apron, and the cutting began. The operation accomplished, the surgeon would look around with a deep sigh, and then - "Next!"

(7) After the American Civil War Carl Schurz wrote about a meeting with John S. Mosby and his Partisan Rangers.

Perhaps two hundred yards ahead of us, we observed a troop of ten or twelve of them, who advanced towards us. They looked rather ragged, and I took them for teamsters or similar folk. But one of the orderlies cried out: "There are the rebels!" And true enough, they were a band of Mosby's guerrillas. Now they came up at a gallop, and in a minute they were among us. While we whipped out our revolvers, I shouted to my bugler: "Sound the advance, double-quick!" which he did; and there was an instant "double-quick" signal in response from the infantry patrol close behind us. We had a lively, but, as to my party, harmless conversation with revolvers for a few seconds, whereupon the guerrillas, no doubt frightened by the shouts of the patrol coming at a run, hastily turned tail and galloped down the road, leaving in our hands one prisoner and two horses.

(8) Carl Schurz wrote about the relative merits of William Sherman, Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee in his autobiography published in 1906.

In the opinion of many competent persons, he was the ablest commander of them all. I remember a remarkable utterance of his when we were speaking of Grant's campaign. "There was a difference," Sherman said, "between Grant's and my way of looking at things. Grant never cared a damn about what was going on behind the enemy's lines, but it often scared me like the devil." He admitted, and justly so, that some of Grant's successes were owing to this very fact, but also some of his most conspicuous failures. Grant believed in hammering - Sherman in maneuvering. It had been the habit of the generals commanding the Army of the Potomac to cross the Rappahannock, to get their drubbing from Lee, and then promptly to retreat and recross the Rappahannock again in retreat. He sturdily went on, hammering and hammering, and, with his vastly superior resources, finally hammered Lee's army to pieces, but with a most dreadful sacrifice of life on his own part. Now, comparing Grant's campaign for the taking of Richmond with Sherman's campaign for the taking of Atlanta - without losing sight of any of the differences of their respective situations - we may well arrive at the conclusion that Sherman was the superior strategist and the greater general.

(9) Carl Schurz was with General William Sherman when he heard about the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

Sherman received a telegraphic message from Secretary Stanton, containing the announcement of the assassination of President Lincoln. The terrible news was kept secret from our troops, to be revealed to them by general order the next day. I well remember the effect the announcement had upon them. The camps, which for two days had been fairly resounding with jubilation over the advent of peace, suddenly fell into gloomy stillness. The soldiers admired their great generals, but their good "Father Abraham", they loved.

(10) Carl Schurz wrote about the differences between Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson in his autobiography published in 1906.

It was pretended at the time and it has since been asserted by historians and publicists that Mr. Johnson's Reconstruction policy was only a continuation of that of Mr. Lincoln. This is true only in a superficial sense, but not in reality. Mr. Lincoln had indeed put forth reconstruction plans which contemplated an early restoration of some of the rebel states. But he had done this while the Civil War was still going on, and for the evident purpose of encouraging loyal movements in those States and of weakening the Confederate State government there. Had he lived, he would have as ardently wished to stop bloodshed and to reunite as he ever did. But is it to be supposed for a moment that, seeing the late master class in the South intent upon subjecting the freedmen again to a system very much akin to slavery, Lincoln would have consented to abandon those freemen to the mercies of that master class?

(11) Carl Schurz, speech at Chicago's World Fair (1893)

I have always been in favor of a healthy Americanization, but that does not mean a complete disavowal of our German heritage. It means that our character should take on the best of that which is American, and combine it with the best of that which is German. By doing this, we can best serve the American people and their civilization.