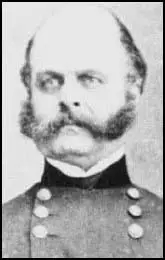

Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Burnside was born in Liberty on 23rd May, 1824. He graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1847. He served in the Mexican War but resigned his commission in 1853.

Burnside settled in Bristol, Rhode Island, where he became involved in the manufacture of firearms. In 1856 Burnside invented a highly successful breech-loading rifle.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War Burnside became a colonel in the Rhode Island Volunteers. After fighting successfully at Bull Run he was promoted to brigadier general in the Union Army. He served in North Carolina and developed a reputation as a dashing commander and during this period he is said to have popularized the fashion of side whiskers (later known as sideburns).

Burnside took part in the battle at Antietam (September, 1862) and afterwards President Abraham Lincoln asked him to replace George McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac. After the complaints that had been made by President Abraham Lincoln and the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, about the inaction of the Union Army, Burnside was determined to immediately launch an attack on the Confederate Army.

With a force of 122,000, Burnside, Joseph Hooker, Edwin Sumner, William Franklin attacked General Robert E. Lee and his army of 78,500, at Fredericksburg, Virginia, on 13th December. Sharpshooters based in the town initially delayed the Union Army from building a ponton bridge across the Rappahnnock River.

After clearing out the snipers the federal forces had the problem of mounting frontal assaults against troops commanded by James Longstreet. At the end of the day the Union Army had 12,700 men killed or wounded. The well protected Confederate Army suffered losses of 5,300. Ambrose Burnside wanted to renew the attack the following morning but was talked out of it by his commanders.

After the disastrous battle at Fredericksburg Burnside was replaced by Joseph Hooker. Burnside was put in charge of the Army of Ohio in March, 1863 and succeeded in capturing Morgan's Raiders and performed well at the siege of Knoxville.

Returning to the east he took part in the Wilderness campaign before organizing regiment of Pennsylvania coalminers to construct tunnels and place dynamite under the Confederate Army front lines at Petersburg. It was exploded on the 30th June and US Colored troops were sent forward to take control of the craters that had been formed. However, these troops were not given adequate support and the Confederate troops were soon able to recover its positions. Thousands of captured black soldiers were now murdered by angry Southerners.

After the war Burnside was successful in his engineering business and served as governor of Rhode Island (1866-69) and as a US Senator (1875-81). Ambrose Burnside died in Bristol, Rhode Island on 13th September, 1881.

Primary Sources

(1) Carl Schurz served under Ambrose Burnside during the American Civil War. He wrote about his commander and the battle of Fredericksburg in his autobiography published in 1906.

When McClellan at last had crossed the Potomac and Richmond, the President removed him from his command and put General Burnside in his place. The selection of Burnside for so great a responsibility was not a happy one. He was a very patriotic man whose heart was in his work, and his sincerity, frankness, and amiability of manner made everybody like him. But he was not a great general, and he felt, himself, that the task to which he had been assigned was too heavy for his shoulders. The complaint against McClellan having been his slowness to act. Burnside resolved to act at once. The plan of campaign he conceived was to cross the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg, and thence to operate upon Richmond.

The battle began on December 13th, 1862, soon after sunrise, under a gray wintry sky. Standing inactive in reserve, we eagerly listened to the booming of the guns, hoping that we should hear the main attack move forward. At eleven o'clock Burnside ordered the assault from Fredericksburg upon Marye's Heights, Lee's fortified position. Our men advanced with enthusiasm. A fearful fire of artillery and musketry greeted them. Now they would stop a moment, then plunger forward again.

Through our glasses we saw them fall by hundreds, and their bodies dot the ground. As they approached Lee's entrenched position, sheet after sheet of flame shot forth from the heights, tearing fearful gaps in our lines. There was no running back of our men. They would sometimes stop or recoil only a little distance, but then doggedly resume the advance. A column rushing forward with charged bayonets almost seemed to reach the enemy's ramparts, but then to melt away.

Here and there large numbers of our men, within easy range of the enemy's musketry, would suddenly drop like tall grass swept down with a scythe. They had thrown themselves upon the ground to let the leaden hail pass over them, and under it to advance, crawling. It was all in vain. The enemy's line was so well posted and protected by a canal and a sunken road and stone walls and entrenchments skillfully thrown up, and so well defended, that it could not be carried by a front assault.

The early coming of night was most welcome. A longer day would have been only a prolonged butchery. And we, of the reserve, stood there while daylight lasted, seeing it all, burning to go to the aid of our brave comrades, but knowing also that it would be useless. Hot tears of rage and of pitying sympathy ran down many a weather-beaten cheek. No more horrible and torturing spectacle could have been imagined.

General Burnside bore himself like an honorable man. During the battle he had proposed to put himself personally at the head of his old corps, the Ninth, and to lead it in the assault. Reluctantly he desisted, yielding to the earnest protests of his generals. After the defeat he unhesitatingly shouldered the whole responsibility for the disaster. He not only did not accuse the troops of any shortcomings, but in the highest terms he praised their courage and extreme gallantry. He blamed only himself.

(2) In 1862 Henry Villard met General Ambrose Burnside. He wrote about him in his Memoirs: Journalist and Financier (1904)

There was nothing in his exterior or in his conversation that indicated intellectual eminence or executive ability of a high order. He inspired confidence in his honesty of purpose and ardent loyalty, but it was not possible that any experienced judge of men should be impressed with him as a great man.