George McClellan

George McClellan, the son of a surgeon, he was born in Philadelphia on 3rd December, 1826. He was educated at the University of Pennsylvania and the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where in 1846 he graduated second in his class.

McClellan was appointed to the staff of General Winfield Scott during the Mexican War (1846-48) and won three brevets for gallant conduct. He taught military engineering at West Point (1848-51) and in 1855 was sent to observe the Crimean War in order to obtain the latest information on European warfare.

McClellan left the United States Army in 1857 to become chief of engineering for the Illinois Central Railroad where he became acquainted with Abraham Lincoln, the company's attorney. In 1860 McClellan became president of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad.

Although McClellan was a member of the Democratic Party he offered his services to President Abraham Lincoln on the outbreak of the American Civil War. He was placed in command of the Department of the Ohio with responsibility for holding the western area of Virginia. He did this successfully and after the Union Army was defeated by the Confederate Army at Bull Run, Lincoln appointed McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac. McClellan insisted that his army should undertake any new offensives until his new troops were fully trained.

In November, 1861 McClellan, who was only 34 years old, was made commander in chief of the Union Army. He developed a strategy to defeat the Confederate Army that included an army of 273,000 men. His plan was to invade Virginia from the sea and to seize Richmond and the other major cities in the South. McClellan believed that to keep resistance to a minimum, it should be made clear that the Union forces would not interfere with slavery and would help put down any slave insurrections.

McClellan appointed Allan Pinkerton to employ his agents to spy on the Confederate Army. His reports exaggerated the size of the enemy and McClellan was unwilling to launch an attack until he had more soldiers available. Under pressure from Radical Republicans in Congress, Abraham Lincoln decided in January, 1862, to appoint Edwin M. Stanton as his new Secretary of War.

Soon after this appointment Abraham Lincoln ordered McClellan to appear before a committee investigating the way the war was being fought. On 15th January, 1862, McClellan had to face the hostile questioning of Benjamin Wade and Zachariah Chandler. Wade asked McClellan why he was refusing to attack the Confederate Army. He replied that he had to prepare the proper routes of retreat. Chandler then said: "General McClellan, if I understand you correctly, before you strike at the rebels you want to be sure of plenty of room so that you can run in case they strike back." Wade added "Or in case you get scared". After McClellan left the room, Wade and Chandler came to the conclusion that McClellan was guilty of "infernal, unmitigated cowardice".

As a result of this meeting Abraham Lincoln decided he must find a way to force McClellan into action. On 31st January he issued General War Order Number One. This ordered McClellan to begin the offensive against the enemy before the 22nd February. Lincoln also insisted on being consulted about McClellan's military plans. Lincoln disagreed with McClellan's desire to attack Richmond from the east. Lincoln only gave in when the division commanders voted 8 to 4 in favour of McClellan's strategy. However, Lincoln no longer had confidence in McClellan and removed him from supreme command of the Union Army. He also insisted that McClellan left 30,000 men behind to defend Washington.

During the summer of 1862, McClellan and the Army of the Potomac, took part in what became known as the Peninsular Campaign. The main objective was to capture Richmond, the base of the Confederate government. McClellan and his 115,000 troops encountered the Confederate Army at Williamsburg on 5th May. After a brief battle the Confederate forces retreated South.

McClellan moved his troops into the Shenandoah Valley and along with John C. Fremont, Irvin McDowell and Nathaniel Banks surrounded Thomas Stonewall Jackson and his 17,000 man army. First Jackson attacked John C. Fremont at Cross Keys before turning on Irvin McDowell at Port Republic. Jackson then rushed his troops east to join up with Joseph E. Johnston and the Confederate forces fighting McClellan in the suburbs the city.

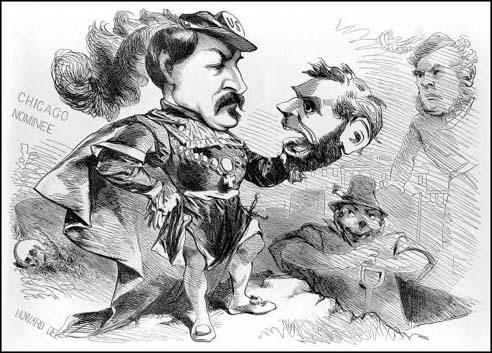

published in the New York World during the presidential campaign of 1864.

General Joseph E. Johnston with some 41,800 men counter-attacked McClellan's slightly larger army at Fair Oaks. The Union Army lost 5,031 men and the Confederate Army 6,134. Johnson was badly wounded during the battle and General Robert E. Lee now took command of the Confederate forces.

Major General John Pope, the commander of the new Army of Virginia, was instructed to move east to Blue Ridge Mountains towards Charlottesville. It was hoped that this move would help McClellan by drawing Robert E. Lee away from defending Richmond. Lee's 80,000 troops were now faced with the prospect of fighting two large armies: McClellan (90,000) and Pope (50,000)

Joined by Thomas Stonewall Jackson, the Confederate troops constantly attacked McClellan and on 27th June they broke through at Gaines Mill. Convinced he was outnumbered, McClellan retreated to James River. Abraham Lincoln, frustrated by McClellan's lack of success, sent in Major General John Pope, but he was easily beaten back by Jackson.

McClellan wrote to Abraham Lincoln complaining that a lack of resources was making it impossible to defeat the Confederate forces. He also made it clear that he was unwilling to employ tactics that would result in heavy casualties. He claimed that "ever poor fellow that is killed or wounded almost haunts me!" On 1st July, 1862, McClellan and Lincoln met at Harrison Landing. McClellan once again insisted that the war should be waged against the Confederate Army and not slavery.

Salmon Chase (Secretary of the Treasury), Edwin M. Stanton (Secretary of War) and vice president Hannibal Hamlin, who were all strong opponents of slavery, led the campaign to have McClellan sacked. Unwilling to do this, Abraham Lincoln decided to put McClellan in charge of all forces in the Washington area.

After the second battle of Bull Run, General Robert E. Lee decided to invade Maryland and Pennsylvania. On 10th September, 1862, he sent Thomas Stonewall Jackson to capture the Union Army garrison at Harper's Ferry and moved the rest of his troops to Antietam Creek. When McClellan heard that the Confederate Army had been divided, he decided to attack Lee. However, the Harper's Ferry garrison surrendered on 15th September and some of the men were able to rejoin Lee.

On the morning of 17th September, 1862, McClellan and Major General Ambrose Burnside attacked Robert E. Lee at Antietam. The Union Army had over 75,300 troops against 37,330 Confederate soldiers. Lee held out until Ambrose Hill and reinforcements arrived from Harper's Ferry. The following day Lee and his army crossed the Potomac into Virginia unhindered.

It was the most costly day of the war with the Union Army having 2,108 killed, 9,549 wounded and 753 missing. The Confederate Army had 2,700 killed, 9,024 wounded and 2,000 missing. As a result of being unable to achieve a decisive victory at Antietam, Abraham Lincoln postponed the attempt to capture Richmond. Lincoln was also angry that McClellan with his superior forces had not pursued Robert E. Lee across the Potomac

Abraham Lincoln now wanted McClellan to go on the offensive against the Confederate Army. However, McClellan refused to move, complaining that he needed fresh horses. Radical Republicans now began to openly question McClellan's loyalty. "Could the commander be loyal who had opposed all previous forward movements, and only made this advance after the enemy had been evacuated" wrote George W. Julian. Whereas William P. Fessenden came to the conclusion that McClellan was "utterly unfit for his position".

Frustrated by McClellan unwillingness to attack, Abraham Lincoln recalled him to to Washington with the words: "My dear McClellan: If you don't want to use the Army I should like to borrow it for a while." On 7th November Lincoln removed McClellan from all commands and replaced him with Ambrose Burnside.

In 1864 stories began to circulate that McClellan was seeking the presidential nomination of the Democratic Party. Worried by the prospect of competing with the former head of the Union Army, it is claimed that Lincoln offered McClellan a new command in Virginia. McClellan refused and accepted the nomination. In an attempt to obtain unity, Lincoln named a Southern Democrat, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, as his running mate.

During the campaign McClellan declared the war a "failure" and urged "immediate efforts for a cessation of hostilities, with a view to an ultimate convention of the states, or other peaceable means, to the end that peace may be restored on the basis of the federal Union of the States". However, McClellan added that this could happen when "our adversaries are willing to negotiate upon the basis of reunion." McClellan made it clear that he disliked slavery because it weakened the country but he opposed "forcible abolition as an object of the war or a necessary condition of peace and reunion."

The victories of Ulysses S. Grant, William Sherman, George Meade, Philip Sheridan and George H. Thomas in the summer of 1864 reinforced the idea that the Union Army was close to bringing the war to an end. This helped Lincoln's presidential campaign and with 2,216,067 votes, comfortably beat McClellan (1,808,725) in the election. McClellan carried only Delaware, Kentucky and New Jersey.

After the war McClellan he spent time in Europe before returning to serve as chief engineer of the New York Department of Docks (1870-72) and in 1872 became president of the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad. He also served as governor of New Jersey from 1878 to 1881. George McClellan died on 29th October, 1885, in Orange, New Jersey.

Primary Sources

(1) In July, 1861, Oliver Howard joined the Army of Potomac under the command of General George McClellan. Howard wrote about McClellan in his autobiography published in 1907.

My first sight of McClellan was in 1850, when I was a cadet at West Point. He had then but recently returned from Mexico, where he had gained two brevets of honor. He was popular and handsome and a captain of engineers, and if there was one commissioned officer more than another who had universal notice among the young gentlemen of the academy it was he, himself a young man, a staff officer of a scientific turn who had been in several battles and had played everywhere a distinguished part.

Eleven years later, after his arrival in Washington, July 23, 1861, an occasion brought me, while standing amid a vast multitude of other observers, a fresh glimpse of McClellan. He was now a major general and fittingly mounted. His record, from a brilliant campaign in West Virginia, and the urgent demand of the Administration for the ablest military man to lift us up from the valley of our existing humiliation, instantly brought this officer to the knowledge and scrutiny of the Government and the people.

(2) General George McClellan, letter sent to officers in the Army of Potomac (12th November, 1861)

As far as military necessity will permit, religiously respect the constitutional rights of all. Be careful so to treat the unarmed inhabitants as to contract, not widen, the breach existing between us and the rebels. It should be out constant aim to make it apparent to all that their property, their comfort, and their personal safety will be best preserved by adhering to the cause of the Union.

(3) In his autobiography General Oliver Howard commented on the way that Abraham Lincoln treated General George McClellan during the early months of 1862.

Mr. Lincoln evidently had begun to distrust McClellan. There was growing opposition to him everywhere for political reasons. Think of the antislavery views of Stanton and Chase; of the growing antislavery sentiments of the congressional committee on the conduct of war; think of the number of generals like Fremont, Butler, Banks, Hunter, and others in everyday correspondence with the Cabinet, whose convictions were already strong that the slaves should be set free; think, too, of the Republican press constantly becoming more and more of the same opinion and the masses of the people really leading the press. McClellan's friends in the army had often offended the Northern press. In his name radical antislavery correspondents had been expelled from the army.

(4) George McClellan, letter to Edwin M. Stanton after the battle at Gaines Mill (28th June, 1862)

I have lost this battle because my force was too small. I have seen too many dead and wounded comrades to feel otherwise than this government has not sustained this army. If you not do so now the game is lost. If I save this army now, I tell you plainly that I owe no thanks to you or any other person in Washington. You have done the best to sacrifice this army.

(5) George McClellan, letter to Abraham Lincoln (7th July, 1862)

The rebellion has assumed the character of a war; as such it should be regarded, and it should be conducted upon the highest principles known to Christian civilization. It should not be a war looking to the subjugation of the people of any state. It should not be a war upon population but against armed forces and political organization of states, or forcible abolition of slavery should be contemplated for a moment.

In carrying out any system of policy which you may form, you will require a commander in chief of the Army, one who possesses your confidence, understands your views, and who is competent to execute your orders by directing the military forces of the nation to the accomplishment of the objects by you proposed. I do not ask that place for myself. I am willing to serve you in such position as you may assign me, and I will do so as faithfully as ever subordinate served superior.

(6) Salmon Chase had severe doubts about the wisdom of appointing George McClellan as a senior commander. He wrote about his fears to Zachariah Chandler on 20th September, 1862.

Of course the action of the President in placing General McClellan in command was not prompted by me. I thought that there were brave, capable and loyal officers, such as Hooker, Sumner, Burnside and many more who might be named, to whom the command of armies might be more safely and much more properly entrusted. The President thought otherwise, and I must do all I can to make his decision useful to the country.

(7) Carl Schurz wrote about George McClellan and Antietam in his autobiography published in 1906.

On the 17th of September, the battle of Antietam was fought, in which McClellan might have made a victory of immense consequence, had he not, with his usual indecision and procrastination, let slip the moments when he could easily have beaten the divided enemy in detail. As it was, General Lee came near being justified in calling Antietam a "drawn battle". He withdrew almost unmolested from the presence of our army across the Potomac.

(8) James Garfield, like many officers in the Army of the Potomac, was highly critical of his commander, General George McClellan (13th October, 1862)

All my former opinions of McClellan are confirmed. His late campaign in Maryland has been most shameful. He has lain perfectly idle 27 days since the last battle with a force almost twice the number of the rebel army and has been constantly been asking for reinforcements. All three (Edwin Stanton, Abraham Lincoln, Henry Halleck) desire to get rid of McClellan and two or three times have been at the point of removing him, but have lacked the courage. Stanton would have done it but was not allowed - the President would have done it, but feared the Border States and the army - Halleck would have done it, but claimed the responsibility should not be placed on his shoulders. It is still being agitated and I think it is to be done soon, but I believe they are waiting for the elections to be over - lest it may strengthen the Peace Democrats who will praise McClellan to the skies.

(9) Henry Villard worked for the New York Tribune during the American Civil War. In his memoirs he wrote about why McClellan was sacked.

The President's proclamation of the abolition of slavery of September 22 had met with strong opposition in the border States and among the Democrats of the free States, especially in New York, Ohio, and Indiana. It was known that McClellan, and the generals nearest to him, were also opposed to this portentous act. It was proclaimed by the Democratic press that his relief from active command was due to his hostility to it, and a concession to the Abolitionists, who then, as I could personally confirm, still seemed to many Union generals no better than rebels. General McClellan did nothing to disclaim this pseudo-political martyrdom, which was certainly a convenient cloak for the real cause of his dismissal - his military shortcomings.

(10) In 1867 John Singleton Mosby, was interviewed in the Philadelphia Post about the merits of the different generals in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Whom do you consider the ablest General on the Federal side?" "McClellan, by all odds. I think he is the only man on the Federal side who could have organized the army as it was. Grant had, of course, more successes in the field in the latter part of the war, but Grant only came in to reap the benefits of McClellan's previous efforts. At the same time, I do not wish to disparage General Grant, for he has many abilities, but if Grant had commanded during the first years of the war, we would have gained our independence. Grant's policy of attacking would have been a blessing to us, for we lost more by inaction than we would have lost in battle. After the first Manassas the army took a sort of 'dry rot', and we lost more men by camp diseases than we would have by fighting."

(11) George McClellan, McClellan's Own Story (1887)

Had I been successful in my first campaign, the rebellion would perhaps have been terminated without the immediate abolition of slavery. I believe that the leaders of the radical branch of the Republican Party preferred political control of one section of a divided country to being in the minority in a restored Union. Not only did these people desire the abolition of slavery, but its abolition in such a manner and under such circumstances that the slaves would at once be endowed with the electoral franchise and permanent control thus be secured through the votes of the ignorant slaves.

(12) George McClellan, McClellan's Own Story (1887)

Of all the men whom I have encountered in high position Halleck was the most hopelessly stupid. It was more difficult to get an idea through his head than can be conceived by any one who never made the attempt. I do not think he ever had a correct military idea from beginning to end.

A day or two before Halleck arrived in Washington Stanton came to caution me against trusting Halleck, who was, he said, probably the greatest scoundrel and most barefaced villain in America; he said that he was totally destitute of principle, and that in the Almaden Quicksilver case he had convicted Halleck of perjury in open court. When Halleck arrived he came to caution me against Stanton, repeating almost precisely the same words that Stanton had employed.

(13) After the American Civil War, the journalist, Noah Brooks, claimed that in an interview in April, 1863, Abraham Lincoln, explained why he was reluctant to sack General George McClellan.

I kept McClellan in command after I had expected that he would win victories, simply because I knew that his dismissal would provoke popular indignation and shake the faith of the people in the final success of the war.

(14) Abraham Lincoln, in discussion with journalists about General George McClellan (March, 1863)

I do not, as some do, regard McClellan either as a traitor or an officer without capacity. He sometimes has bad counselors, but he is loyal, and he has some fine military qualities. I adhered to him after nearly all my constitutional advisers lost faith in him. But do you want to know when I gave him up? It was after the battle of Antietam. The Blue Ridge was then between our army and Lee's. I directed McClellan peremptorily to move on Richmond. It was eleven days before he crossed his first man over the Potomac; it was eleven days after that before he crossed the last man. Thus he was twenty-two days in passing the river at a much easier and more practicable ford than that where Lee crossed his entire army between dark one night and daylight the next morning. That was the last grain of sand which broke the camel's back. I relieved McClellan at once.