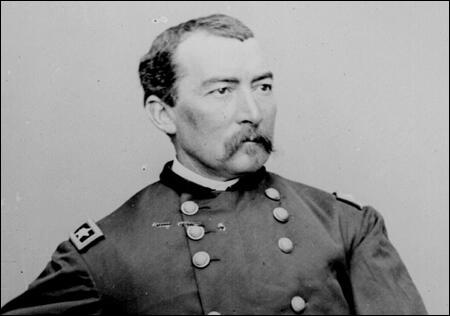

Philip Sheridan

Philip Sheridan was born in Albany, New York, on 6th March, 1831. He studied at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point but was involved in a serious breach of discipline after attacking another soldier with a bayonet. He graduated in 1853 and after joining the United States Army spent most of the next nine years defending frontier posts.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War Sheridan was given an administrative post in St. Louis. Accused of corruption, Sheridan was saved from being court-martialed by General Henry Halleck who appointed him colonel of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry. In July he led a highly successful attack on the Confederate Army at Booneville, Mississippi.

As a result of this action Sheridan was made a brigadier general. He served with distinction at Perryville (October, 1862) and Stones River (December, 1862) and Chickamauga (September, 1863).

In March, 1864, Ulysses S. Grant was named lieutenant general and the commander of the Union Army. He joined the Army of the Potomac and appointed Sheridan as head of the Cavalry Corps. They crossed the Rapidan and entered the Wilderness. When Robert E. Lee heard the news he sent in his troops, hoping that the Union's superior artillery and cavalry would be offset by the heavy underbrush of the Wilderness. Fighting began on the 5th May and two days later smoldering paper cartridges set fire to dry leaves and around 200 wounded men were either suffocated or burned to death. Of the 88,892 men that Grant took into the Wilderness, 14,283 were casualties and 3,383 were reported missing. Lee lost 7,750 men during the fighting.

After the battle Ulysses S. Grant moved south and on May 26th sent Sheridan and his cavalry ahead to capture Cold Harbor from the Confederate Army. Lee was forced to abandon Cold Harbor and his whole army well dug in by the time the rest of the Union Army arrived. Grant's ordered a direct assault but afterwards admitted this was a mistake losing 12,000 men "without benefit to compensate".

In May 1864 Sheridan led the attacks on Richmond. During one of these battles at Yellow Tavern, his legendary opponent, Jeb Stuart was killed. Ulysses S. Grant rated Sheridan very highly and in August , 1864 he gave him the command of the Shenandoah Valley campaign. Sheridan and 40,000 soldiers entered the valley and soon encountered troops led by Jubal Early who had just returned from Washington. After a series of minor defeats Sheridan eventually gained the upper hand. His men now burnt and destroyed anything of value in the area and after defeating Early in another large-scale battle on 19th October, the Union Army took control of the Shenandoah Valley.

On 1st April Sheridan attacked at Five Forks. The Confederates, led by Major General George Pickett, were overwhelmed and lost 5,200 men. On hearing the news, Robert E. Lee decided to abandon Richmond and President Jefferson Davis, his family and government officials, was forced to flee from the city.

After the war Sheridan was military governor of Louisiana and Texas, but his Reconstruction measures made him unpopular with President Andrew Johnson and he was removed from office. He remained in the United States Army and in 1884 he succeeded William T. Sherman as commander in chief. His autobiography, Personal Memoirs was published in the year of his death.

Primary Sources

(1) Ulysses Grant, Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant (1885)

The Shenandoah Valley was very important to the Confederates, because it was the principal storehouse they now had for feeding their armies about Richmond. It was well known that they would make a desperate struggle to maintain it. It had been the source of a great deal of trouble to us heretofore to guard that outlet to the north, partly because of the incompetency of some of the commanders, but chiefly because of the interference from Washington. It seemed to be the policy of General Halleck nd Secretary Stanton to keep any force sent there, in pursuit of the invading army, moving right and left so as to keep between the enemy and our capital; and, generally speaking, they pursued this policy until all knowledge of the whereabouts of the enemy was lost. They were left, therefore, free to supply themselves with horses, beef cattle, and such provisions as they could carry away from Western Maryland and Pennsylvania. I was determined to put a stop to this.

I had previously asked to have Sheridan assigned to that command but Mr. Stanton objected, on the ground that he was too young for such an important a command. On 1st August, 1864, I sent the following orders to Major-General Halleck: "I am sending General Sheridan for temporary duty whilst the enemy is being expelled from the border. Unless General Hunter is in the field in person, I want Sheridan put in command of all the troops in the field with instructions to put himself south of the enemy and follow him to death. Wherever the enemy goes let our troops go also."

(2) John Singleton Mosby, letter to Philip Sheridan (11th November, 1864)

Some time in the month of September, during my absence from my command, six of my men who had been captured by your forces, were hung and shot in the streets of Front Royal, by order and in the immediate presence of Brigadier-General Custer. Since then another (captured by a Colonel Powell on a plundering expedition into Rappahannock) shared a similar fate. A label affixed to the coat of one of the murdered men declared "that this would be the fate of Mosby and all his men."

Since the murder of my men, not less than seven hundred prisoners, including many officers of high rank, captured from your army by this command have been forwarded to Richmond; but the execution of my purpose of retaliation was deferred, in order, as far as possible, to confine its operation to the men of Custer and Powell. Accordingly, on the 6th instant, seven of your men were, by my order, executed on the Valley Pike - your highway of travel.

Hereafter, any prisoners falling into my hands will be treated with the kindness due to their condition, unless some new act of barbarity shall compel me, reluctantly, to adopt a line of policy repugnant to humanity.