Robert Blincoe

Robert Blincoe was born in 1792. At four years old Blincoe was placed in St. Pancras Workhouse, London. He was later told that his family name was Blincoe but he never discovered what happened to his parents. At the age of six Robert was sent to work as a chimney boy. As Nicholas Blincoe, his great-great-great-grandson, has pointed out: "As coal replaced wood-burning grates, chimneys became narrower to create a more intense draught. This was why small boys were needed, but the work was dangerous - the children risked injury, suffocation, lung disease and scrotal cancer as they climbed the chimney stacks. Robert was warned by older inmates not to put himself forward." However, Robert was not a success and after a few months he was returned to the workhouse.

In 1799, Lamberts recruited Robert and eighty other boys and girls from St. Pancras Workhouse. The boys were to be instructed in the trade of stocking weaving and the girls in lacemaking at Lowdam Mill, situated ten miles from Nottingham. Blincoe completed his apprenticeship in 1813, worked as an adult operative until 1817, when he set up his own small cotton-spinning business. Blincoe married a woman called Martha in 1819.

John Brown, a journalist from Bolton, met Robert Blincoe in 1822. He later explained: "It was in the spring of 1822, after having devoted a considerable time to the investigating of the effect of the manufacturing system, and factory establishments, on the health and morals of the manufacturing populace, that I first heard of the extraordinary sufferings of Robert Blincoe. At the same time, I was told of his earnest wish that those sufferings should, for the protection of the rising generation of parish children, be laid before the world. If this young man had not consigned to a cotton-factory, he would probably have been strong, healthy, and well grown; instead of which, he is diminutive as to statue, and his knees are grievously distorted."

Brown interviewed Blincoe for an article he was writing on child labour. Brown found the story so fascinating he decided to write Blincoe's biography. John Brown gave the biography to his friend Richard Carlile who was active in the campaign for factory legislation. Later that year John Brown committed suicide.

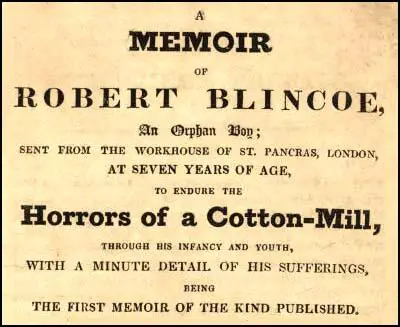

Robert Carlile eventually decided to publish Robert Blincoe's Memoir in his radical newspaper, The Lion. The story appeared in five weekly episodes from 25th January to 22nd February 1828. The story also appeared in Carlile's The Poor Man's Advocate. Five years later, John Doherty published Robert Blincoe's Memoir in pamphlet form.

As a result of a fire in 1828, Robert Blincoe's spinning machinery was destroyed. Unable to pay his debts, Blincoe was imprisoned in Lancaster Castle. After his release he became a cotton-waste dealer and his wife ran a grocer's shop.

Blincoe's business was successful and he was able to pay for his three children to be educated. One of his sons went on to graduate from Queens College, University of Cambridge to become a Church of England clergyman.

In January 1837, Richard Bentley, the owner of the journal, Bentley's Miscellany, agreed to publish Oliver Twist, a serial written by Charles Dickens. It has been argued by John Waller, the author of Oliver: The Real Oliver Twist (2005) argues that he took his story from the memoirs of Blincoe.

Robert Blincoe carried on the business of a cotton-waste dealer in Turner Street. Abel Heywood got to know him in Manchester during this period: "He was a little man in height, his legs being very crooked, the result of his early life in a cotton factory."

Robert Blincoe died of bronchitis at the home of his daughter in Gunco Lane, Macclesfield in 1860.

Primary Sources

(1) John Brown, A Memoir of Robert Blincoe (1828)

In the summer of 1799 a rumour circulated that there was going to be an agreement between the church wardens and the overseers of St. Pancras Workhouse and the owner of a great cotton mill, near Nottingham. The children were told that when they arrived at the cotton mill, they would be transformed into ladies and gentlemen: that they would be fed on roast beef and plum pudding, be allowed to ride their masters' horses, and have silver watches, and plenty of cash in their pockets. In August 1799, eighty boys and girls, who were seven years old, or were considered to be that age, became parish apprentices till they had acquired the age of twenty-one.

(2) John Brown, A Memoir of Robert Blincoe (1828)

The young strangers were conducted into a spacious room with long, narrow tables, and wooden benches. They were ordered to sit down at these tables - the boys and girls apart. The supper set before them consisted of milk-porridge, of a very blue complexion! The bread was partly made of rye, very black, and so soft, they could scarcely swallow it, as it stuck to their teeth. Where is our roast beef and plum-pudding, he said to himself.

The apprentices from the mill arrived. The boys had nothing on but a shirt and trousers. Their coarse shirts were entirely open at the neck, and their hair looked as if a comb had seldom, if ever, been applied! The girls, like the boys, destitute of shoes and stockings. On their first entrance, some of the old apprentices took a view of the strangers; but the great bulk first looked for their supper, which consisted of new potatoes, distributed at a hatch door, that opened into the common room from the kitchen.

There was no cloth laid on the tables, to which the newcomers had been accustomed in the workhouse - no plates, nor knives, nor forks. At a signal given, the apprentices rushed to this door, and each, as he made way, received his portion, and withdrew to his place at the table. Blincoe was startled, seeing the boys pull out the fore-part of their shirts, and holding it up with both hands, received the hot boiled potatoes allotted for their supper. The girls, less indecently, held up their dirty, greasy aprons, that were saturated with grease and dirt, and having received their allowance, scampered off as hard as they could, to their respective places, where, with a keen appetite, each apprentice devoured her allowance, and seemed anxiously to look about for more. Next, the hungry crew ran to the tables of the newcomers, and voraciously devoured every crust of bread and every drop of porridge they had left.

(3) John Brown, A Memoir of Robert Blincoe (1828)

The room in which Blincoe and several of the boys were deposited, was up two pair of stairs. The bed places were a sort of cribs, built in a double tier all round the chamber. The apprentices slept two in a bed. The governor called the strangers to him and allocated to each his bed-place and bed-fellow, not allowing any two of the newly arrived inmates to sleep together. The boy whom Blincoe was to chum, sprang nimbly into his birth, and without saying a prayer, or anything else, fell asleep before Blincoe could undress himself. When he crept into bed, the stench of the oily clothes and greasy hide of his sleepy comrade, almost turned his stomach.

(4) John Brown, A Memoir of Robert Blincoe (1828)

Blincoe was assigned to a room, over which a man name Smith presided. The task first allotted to him was to pick up the lose cotton, that fell upon the floor. Apparently, nothing could be easier, and he set to with diligence, although much terrified by the whirling motion and noise of the machinery, and not a little affected by the dust and flue which he was half suffocated. Unused to the stench, he soon felt sick, and by constantly stooping, his back ached. Blincoe, therefore, took the liberty to sit down; but this attitude, he soon found, was strictly forbidden in cotton mills. Smith, his task-master, told him he must keep on his legs. He did so, till twelve o'clock, being six hours and a half, without the least intermission.

After Blincoe had been employed in the way described, he was promoted to the more important employment of a roving winder. Being too short of statue, to reach to his work, standing on the floor, he was placed on a block. He was not able by any possible exertion, to keep pace with the machinery. In vain, the poor child declared he was not in his power to move quicker. He was beaten by the overlooker, with great severity. In common, with his fellow apprentices, Blincoe was wholly dependent upon the mercy of the overlookers, whom he found, generally speaking, a set of brutal, ferocious, illiterate ruffians. Blincoe complained to Mr. Baker, the manager, and all he said to him was: "do your work well, and you'll not be beaten." The overlooker, who was in charge of him, had a certain quantity of work to perform in a given time. If every child did not perform his allotted task, the overlooker, and was discharged.

A blacksmith named William Palfrey, who resided in Litton, worked in a room under that where Blincoe was employed. He used to be much disturbed by the shrieks and cries of the boys. According to Blincoe, human blood has often run from an upper to a lower floor. Unable to bear the shrieks of the children, Palfrey used to knock against the floor, so violently, as to force the boards up, and call out "for shame! for shame! are you murdering the children?" By this sort of conduct, the humane blacksmith was a check on the cruelty of the brutal overlookers, as long as he continued in his shop; but he went home at seven o'clock and as soon as Woodward, Merrick and Charnock knew that Palfrey was gone, they beat and knock the apprentices about without moderation.

(5) John Brown, A Memoir of Robert Blincoe (1828)

A girl named Mary Richards, who was thought remarkably handsome when she left the workhouse, and, who was not quite ten years of age, attended a drawing frame, below which, and about a foot from the floor, was a horizontal shaft, by which the frames above were turned. It happened one evening, when her apron was caught by the shaft. In an instant the poor girl was drawn by an irresistible force and dashed on the floor. She uttered the most heart-rending shrieks! Blincoe ran towards her, an agonized and helpless beholder of a scene of horror. He saw her whirled round and round with the shaft - he heard the bones of her arms, legs, thighs, etc. successively snap asunder, crushed, seemingly, to atoms, as the machinery whirled her round, and drew tighter and tighter her body within the works, her blood was scattered over the frame and streamed upon the floor, her head appeared dashed to pieces - at last, her mangled body was jammed in so fast, between the shafts and the floor, that the water being low and the wheels off the gear, it stopped the main shaft. When she was extricated, every bone was found broken - her head dreadfully crushed. She was carried off quite lifeless.

(6) John Brown, A Memoir of Robert Blincoe (1828)

Blincoe hired a warehouse and lived in lodgings. In the year 1819, on Sunday, the 27th June, he happened to be, with several other persons, at the christening of a neighbour's child, where several females were present. An acquaintance of Robert Blincoe's, a jolly butcher, began to jest and jeer him, as to his being single. There was a particular female friend present, whose years, though not approaching old age, out-numbered Blincoe's, and the guests ran their jokes upon her, and some of the company said, Blincoe, get married tomorrow, and then we'll have a good wedding. Upon which, Blincoe, leering a little sideways at the lady, said, "Well, if Martha will have me, I'll take her and marry her tomorrow." She demurely, said "Yes". The next morning they went in a coach from his lodgings in Bank Top and were married in the Old Church.

(7) John Brown described Robert Blincoe aged 30 in 1822.

It was in the spring of 1822, after having devoted a considerable time to the investigating of the effect of the manufacturing system, and factory establishments, on the health and morals of the manufacturing populace, that I first heard of the extraordinary sufferings of Robert Blincoe. At the same time, I was told of his earnest wish that those sufferings should, for the protection of the rising generation of parish children, be laid before the world. If this young man had not consigned to a cotton-factory, he would probably have been strong, healthy, and well grown; instead of which, he is diminutive as to statue, and his knees are grievously distorted.

(8) Robert Blincoe was interviewed by the Employment of Children in Manufactories Committee in 1832.

Question: Have you any children?

Robert Blincoe: Three.

Question: Do you send them to factories?

Robert Blincoe: No; I would rather have them transported to Australia. In the first place, they are standing upon one leg, lifting upon one leg, lifting up one knee; a great part of the day, keeping the ends up from the spindle; I consider that this employment makes many cripples. Then there is the heat and the dust; then there are so many different forms of cruelty used upon them. I would not have a child of mine there because there is not good morals; there is such a lot of them together that they learn mischief.

(9) Abel Heywood of Manchester described Robert Blincoe in 1888.

Robert Blincoe carried on the business of a cotton-waste dealer in Turner Street. He was a little man in height, his legs being very crooked, the result of his early life in a cotton factory.

(10) Nicholas Blincoe, The Guardian (28th September 2005)

The idea that Charles Dickens based Twist on a Blincoe is expounded by John Waller in The Real Oliver Twist, a compelling history of the lives of workhouse children in the industrial revolution. Robert Blincoe, my great-great-great-grandfather, was a workhouse orphan and illegitimate. His life story was serialised in the Lion, a radical newspaper, in 1828 and republished in book form as The Memoirs of Robert Blincoe in 1832. The memoir became a cause célèbre when it was quoted in parliament (where Dickens worked as a reporter), and the focus of a political campaign. Robert, who had been disabled by his upbringing, even appeared on political posters of the 1830s, beneath a slogan borrowed from the abolitionist movement: "Am I Not a Man and a Brother?" Dickens would have known of The Memoirs of Robert Blincoe, but the identification of Oliver with Robert rests chiefly upon the opening chapters of the two books.

Robert Blincoe entered the workhouse in Camden Town (on the site of today's tube station) in 1796, aged about four. He had no recollection of an earlier life. Oliver Twist was born in the workhouse but was immediately packed off to the workhouse farm. In Polanski's uncharacteristically soft-centred film, the farm provokes images of meadowlands and dairies. In fact, the workhouse farm was a euphemism for a baby farm for abandoned children; Dickens' novel paints a grotesque picture of gin-soaked nurses and hungry kids.

In his memoirs, Robert tells how the desire to escape led him to volunteer as an apprentice chimney sweep, though he was only six years old. As coal replaced wood-burning grates, chimneys became narrower to create a more intense draught. This was why small boys were needed, but the work was dangerous - the children risked injury, suffocation, lung disease and scrotal cancer as they climbed the chimney stacks. Robert was warned by older inmates not to put himself forward. In one of the few comic episodes in the memoirs, Robert is pictured grinning enthusiastically in a line of dejected boys, all old enough to know how dangerous a sweep's life could be.