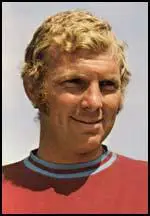

Bobby Moore

Robert "Bobby" Moore, the only son of Robert (Bob) and Doris Moore, was born in Upney Hospital on 12th April 1941, during the Blitz. His aunt, Ena Herbert, recalled: "Little Robert was delivered in Upney hospital... Doris stayed in the hospital that night and came home to Waverley Gardens the next day... That night there was a very heavy German bombing raid and an explosion in the neighbourhood blasted ceilings down and blew windows in... Bob's mother and Bob laid across the baby and Doris to protect them from injury. The raid was so bad they had to evacuate Doris and little Robert from Waverley Gardens, which was near the industrial area, close to the power station on the river, which was a target for the German bombs."

The Moore family lived at 43 Waverley Gardens in Barking and Bobby attended Westbury Primary School. His parents supported Barking Football Club and attended all their home and away games. Moore passed his 11-plus and went to Tom Hood Technical High School in Leyton. Moore later recalled: "The first two months were murder. I was the only boy from my district. Up at seven a.m., on my own on the bus from home to Barking station, train to Wanstead, trolleybus to Leyton, long walk to the school. I was sick with it. I went to the doctor pining for any sort of school in Barking and got a certificate for a transfer on the grounds of travel sickness." However, Moore decided to continue at the school.

School Football

Joan Wright, one of his teachers at Tom Hood Technical High School later recalled: "At school he was a prefect... He was very popular. It was a technical and commercial school and Bobby passed the equivalent of nearly half a dozen 'O' levels in one go. whenever there were pupils who wanted to become footballers and thought they didn't have to try at academic work. I'd point out Bobby Moore as an example to show it is possible to do both."

While at secondary school Moore played for Leyton District Under-13s. During one game he was seen by a West Ham United scout and he was invited to train at Upton Park. Moore found the experience difficult: "I was ordinary. I was lucky to be there. and every time I looked at one of the other lads I knew it. Every one of them had played for Essex or London, and at least been for trials with England Schoolboys. I had nothing. All around me were players with unbelievable ability. They were the same age as me and I was looking up at them and wishing I was that good, that skillful."

Moore later pointed out: "The first time I got a representative game I played for Essex over-15s because they needed a makeshift centre forward. I kept lumbering down the middle until our keeper hit a big up-and-under clearance which their keeper caught as I bundled him into the net... The referee was weak and gave the goal for Essex. Everyone knew it was a joke. Most of all, the lads who knew they were better than me." During this period Moore suffered from an inferiority complex. "The best quality I had was wanting to succeed."

Influence of Malcolm Allison

Moore was invited to train with the West Ham Colts. His ability was noticed by Malcolm Allison, the West Ham United defender who had been asked by Ted Fenton, the club manager, to coach the young players. "Fenton used to pay me £3 extra for training the schoolboys at night. It was then that I found I had a bit of a gift for spotting the boys most likely to make it as professionals.... After a fortnight of training the boys Fenton called me into his office to ask my opinion of the intake." Fenton asked him about Georgie Fenn, who had scored nine goals in one match for England Schoolboys: "I said that I didn't give him much of a chance. I didn't like his attitude, he wasn't interested enough. There didn't seem much of a commitment... At the same time I said that Bobby Moore was going to be a very big player indeed. Everything about his approach was right. He was ready to listen. You could see that already he was seeking perfection."

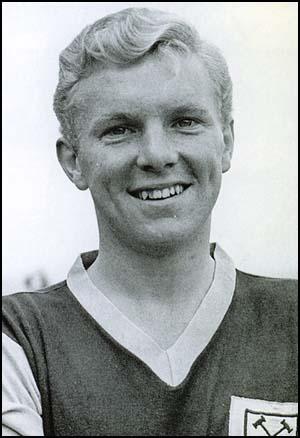

In August 1950, Bobby Moore signed amateur forms for West Ham United. He joined the club full-time after leaving school on 19th July, 1957. Ron Greenwood, was with Fulham when he first saw Bobby Moore play: "I saw Bobby play for London Schoolboys against Glasgow at Stamford Bridge. Even at 16 he had stature, a certain appearance, an awareness of the game others did not possess." When Greenwood became manager of the England Youth team he selected Moore as his captain: "He was thirsty for knowledge and I spent hours talking to him about the game, whenever there was a free moment. When we had trips away he almost raided you for knowledge."

Malcolm Allison also noticed his leadership qualities. "He was very inquisitive. Even then I had spotted his awareness for the game, his ability to recognise things so easily. He had a clever memory and he was very bright. Allison told Moore: "You can read the game, you know what to do... Be in control of yourself. Take control of everything around you. Look big. Think big. Tell people what to do. Be in command." Noel Cantwell was one of the senior players at the club at the time: "Bobby didn't have exceptional ability as an apprentice, although he was always immaculate. He never said very much but was a great listener and a dedicated trainer, always very curious, inquisitive guy who wanted answers. He fastened on to Malcolm Allison and myself because we talked football all the time."

Bobby Moore recalled in his autobiography: "When Malcolm was coaching schoolboys he took a liking to me when I don't think anyone else at West Ham saw anything special in me... I looked up to the man. It's not too strong to say I loved him." Eddie Lewis was a member of the West Ham squad during this period. He observed the help that Allison gave to Moore: "The man deserves a great deal of credit for bringing on the likes of Bobby Moore. As a kid, Bobby was slow, he couldn't head a ball and he couldn't tackle, but such was Malcolm's dedication he was able to help Bobby to become the player he was." Harry Redknapp claims that Allison valued Moore so much that "Malcolm would bring him to training and drive him home."

West Ham Youth Team

Moore put a lot of effort into his training. Geoff Hurst recalled: "I remember how impressed I'd been with this blond-haired youngster from Barking when I first started training at West Ham. When we were doing exercises to strengthen the stomach muscles we had to lie on our backs, raise our legs in the air and hold them there. Try it yourself. If you are not used to it you will quickly discover how painful this can be. Of the 50 or so players doing this exercise the last to lower his legs was Bobby Moore. Always." Frank Lampard agreed: "You could see how some trained better than others, some were good runners, some were bad, but every time you looked over at the first team training, Bobby was the one training hard." John Bond was another player who was impressed with Bobby Moore: "Bobby's ability to intake information was tremendous, he wanted to learn and allowed nothing to interfere with his football. People used to tell him things and he would learn very quickly."

Moore played in a youth match against Chelsea where he marked the highly talented Barry Bridges: "I marked Bridges and followed him all over the field, wherever he went. We drew 0-0 and I was really pleased with myself and I thought Malcolm would give me a pat on the back at the end of the game." Instead Malcolm Allison came into the dressing-room and shouted: "If I ever see you play like that again, I'll never talk to you again. You just followed Bridges all over the field. When your goalkeeper got the ball, you never dropped back and made the goalkeeper roll it out so you could start attacks from the back, did you? When your left-back got it, you didn't drop inside so he could pass it square, so you could chip the ball up to the centre-forward, did you? I want to see you do those things and if you can't, don't talk to me. I'm not giving you any more lifts home."

Moore told Harry Redknapp that this outburst completely changed the way he played the game: "If you look at Bobby's game, he would come and get it off the goalie and play it out, starting attacks, and he would drop off, get the ball from the left-back and chip it into Hurstie's chest. That was an essential part of his game."

On 16th September, 1957, Malcolm Allison was taken ill after a game against Sheffield United. Moore later recalled: "I'd even seen him the day he got the news of his illness. I was a groundstaff boy and I'd gone to Upton Park to collect my wages. I saw Malcolm standing on his own on the balcony at the back of the stand. Tears in his eyes. Big Mal actually crying. He'd been coaching me and coaching me and coaching me but I still didn't feel I knew him well enough to go up and ask what was wrong. When I came out of the office I looked up again and Noel Cantwell was standing with his arm round Malcolm. He'd just been told he'd got T.B."

Allison was suffering from tuberculosis and he had to have a lung removed. Noel Cantwell became the new captain. That season West Ham United won the Second Division championship. The authors of The Essential History of West Ham United point out that Allison was the main reason the club had won promotion: "A footballing visionary who in six short years would revolutionise the club's archaic regime and transform training, coaching techniques and tactics to secure promotion to the first division in 1958".

Bobby Moore's Debut

Allison returned to the club and played several games for the reserves but with only one lung he struggled with his fitness. West Ham had an injury crisis for its home game against Manchester United on 8th September 1958. Malcolm Pyke, Bill Lansdowne and Andy Nelson were all injured. The manager, Ted Fenton asked Noel Cantwell who he should select for the game. Cantwell told Brian Belton, the author of Days of Iron: The Story of West Ham United in the Fifties (1999): "The game against Manchester United was on a Monday night. Fenton called me into the office asking who should play left-half, Allison or Moore. He didn't really want the burden of the decision."

Cantwell added in another interview for the book, Moore than a Legend (1997): "Malcolm came out of hospital and trained while Bobby was cruising along in the reserves. Malcolm was ready for the United game but the vacancy was for a left-half. Malcolm was more of a stopper and it needed someone more mobile. When Ted asked me who to pick, it was a hard decision. The sorcerer or his apprentice?" Cantwell eventually selected Moore over Allison.

Bobby Moore later talked about this decision to Jeff Powell for this book, Bobby Moore: The Life and Times of a Sporting Hero (1997): "The Allison connection could only be dredged up from the bottom of a long, long glass. Even then, Moore probed gingerly at the memory". Eventually Moore told him: " After three or four matches they were top of the First Division, due to play Manchester United on the Monday night, and they had run out of left halves. Billy Lansdowne, Andy Nelson, all of them were unfit. It's got to be me or Malcolm. I'd been a professional for two and a half months and Malcolm had taught me everything I knew. For all the money in the world I wanted to play. For all the money in the world I wanted Malcolm to play because he'd worked like a bastard for this one game in the First Division."

Moore added: "It somehow had to be that when I walked into the dressing room and found out I was playing, Malcolm was the first person I saw. I was embarrassed to look at him. He said Well done. I hope you do well. I knew he meant it but I knew how he felt. For a moment I wanted to push the shirt at him and say Go on, Malcolm. It's yours. Have your game. I can't stop you. Go on, Malcolm. My time will come. But he walked out and I thought maybe my time wouldn't come again. Maybe this would be my only chance. I thought: you've got to be lucky to get the chance, and when the chance comes you've got to be good enough to take it. I went out and played the way Malcolm had always told me to play."

Malcolm Musgrove was a member of the West Ham side that played against Manchester United: "He played in the game as though he'd been in the side for years. I was a lot older than Bobby at the time and I was still a novice, nervous as hell. At the kickoff Bobby stood in the left-half position just looking round. He had an unbelievable temperament. Lots of players have ability, but they haven't got the temperament to make them go even further, as far as they might want to go - Bobby had that temperament."

Moore did a good job marking Ernie Taylor and West Ham won the game 3-2. After the game Malcolm Allison stormed into the dressing-room and confronted Noel Cantwell about the advice he had given Ted Fenton. Cantwell later commented: "How he got to know I had influenced Ted's decision for Bobby to play, I'll never know. I didn't say any more. It was an embarrassing position for me and it soured the night, although I had answered Ted's question with the right choice for the particular match. Later, Malcolm admitted I was right to choose Bobby."

The next game was against Nottingham Forest at home. Moore was dropped from the team after West Ham United lost 4-0. He played only three more games that season as John Smith became the regular left-half. Moore had the same problem in the 1960-61 season. Moore later told Jeff Powell that he "doubted he would ever have broken through had West Ham not sold John Smith to Tottenham". Moore added: "You've got to be lucky even if you know you're good enough to take the chance if it comes. If John hadn't gone to Spurs I might have been a reserve footballer who threw in the towel, gave up the game."

West Ham United Regular

Moore was nearly 20 when he became a regular member of the first-team. He did not approve of the tactics employed by Ted Fenton: "He wanted us to hit long through balls from the half way line. We became the world's best hitters of long through balls to nobody from the half way line. We seemed to lose every match 4-0."

Tom Finney, the veteran winger, spotted Moore's ability as a defender when he was just still a teenager. He pointed out in My Autobiography (2003): "It was an outstanding display from the 19-year-old. Perfect of temperament, he (Moore) always seemed to have so much time on the ball - the sign of a great player. He was strong in the challenge and was never hassled or harried out of his easy stride. He read the game brilliantly and had undisputed star quality."

When Ron Greenwood became manager of the England Under-23 side, he made Moore his captain. Greenwood, was assistant manager at Arsenal at the time, advised Jack Crayston to buy him. According to Moore: “One of Ron’s pet journalists come on my ear about getting away from West Ham to Arsenal… If the chance had come I would have loved to have gone to Arsenal for the same reason that Spurs appealed… a big club. But I suppose when they made the official approaches West Ham knocked them back.”

Moore played in 38 games in the 1960-61 season but the club finished in 16th position. However, his own form was very good. Peter Brabrook, who was playing at Chelsea at the time, found him a very difficult opponent. "When we played West Ham, I always roasted Noel Cantwell, the left-back, who was probably the best left-back in the country. But I could never seem to get past Bobby. He was nowhere near as quick as Noel or me but he never let you get in a position to beat him - he led you into a trap and caught you by the byline or the corner flag."

Ken Brown played alongside Moore during this period: "We were centre-halves for West Ham. I was the stopper and Bobby was the play-maker. My strength was heading and safety first, his strength was control and weighted passing. He could volley or one-touch a pass without looking and you wouldn't struggle to reach it, it would drop at your feet... My natural instinct was to cover him in case he missed a ball but I can't remember him ever bloody missing it. He was so consistent."

On 16th March 1961 the chairman of the club stated: "For some time, Mr Fenton had been working under quite a strain and it was agreed that he should go on sick leave. For the time being, we shall carry on by making certain adjustments in our internal administration." The Ilford Recorder added that: "The Upton Park club are proud of their tradition of never having sacked a manager." This was untrue as Syd King had been dismissed in 1933. Fenton had also been sacked and was replaced by Ron Greenwood.

Malcolm Allison later claimed that "Ted Fenton got the sack. They were rebuilding the stand and he was pinching some bricks and paint. Putting it in the back of the car. One of the directors caught him." Ken Tucker thought he had been dismissed because he had negotiated a reduction in the price of equipment, but was only passing on a percentage of the savings to the club. However, Andy Smillie believes that Fenton was a victim of "player power".

Ron Greenwood and Bobby Moore

Charles Korr, the author of West Ham United: The Making of a Football Club (1986) has argued that the appointment of Greenwood was a break with the past: "When supporters think of managers it is usually in terms of the success of the club. There is little else upon which to judge them. West Ham had been different in this respect because its pre-greenwood managers had been with the club for so long in some capacity that supporters could identify with them. The manager at West Ham was something much more than a transitory employee. Greenwood's employment changed all those perceptions. He was not 'an old boy', and he made no attempt to add affections that would give the impressions that he was part of West Ham tradition."

It is not generally known but Greenwood, who was assistant manager of Arsenal, initially rejected the job. He told one journalist that he was not interested in the job because "If they can get rid of one manager they can get rid of another." He changed his mind when he discovered that Ted Fenton was only the third manager in over 60 years. The other attraction was the quality of West Ham's young players. In fact, Greenwood's first trophy came when West Ham United beat Liverpool 6-5 in the 1963 Youth Cup. The score-line reflects the success and problems of the tactics used by Greenwood.

Bobby Moore, who had played under Ron Greenwood for the England Youth team, was pleased with the appointment. He told Geoff Hurst: "I've played under Ron at England Under-23 level. Things are going to change around here, this chap is incredible on the game." Moore informed his close friend, Jeff Powell: "Ron told me one of his major reasons for coming to West Ham was that he knew he had me there to start building his team around." Greenwood rated Moore very highly: "He was exceptional on the training ground, a coach's dream. Whatever you asked him to do, he could do it. Football came easy to him. It wasn't a question of teaching him, merely a question of honing his considerable abilities... I used him at West Ham as a sweeper, which was then an unknown position. He played loose behind the defence and he thrived there." John Cartwright agreed: "Bobby played it superbly and it was his spot forever more. There have probably been players physically and technically better than Bobby but few tackled as astutely as he did."

Greenwood sold Noel Cantwell to Manchester United and made Phil Woosnam captain. He also purchased the extremely talented Johnny Byrne for £65,000. He played him alongside Geoff Hurst. As Bobby Moore pointed out: "Greenwood turned Geoff Hurst from a bit of a cart-horse at wing-half into a truly great forward. None of us thought Geoff was going to make the switch... Playing up alongside Budgie must have helped. That man was magic." Greenwood also gave Martin Peters his debut. Moore claimed that: "He was virtually a complete player. In addition to all his talent he had vision and awareness and a perfect sense of timing."

In Greenwood's first full season, West Ham United finished in 8th place. At the beginning of the 1962-63 season Greenwood sold Woosnam to Aston Villa and made Moore captain. Greenwood argued: "I made him captain because he was such a natural leader and had everyone's respect... He was desperate to succeed and was a good captain because he didn't ask anybody to do anything he couldn't do."

Ronnie Boyce was one of those who played under Bobby Moore at West Ham: "He was quiet when he was playing. He would never yell... He was forceful when he suggested ideas, without shouting. He spoke quietly and you couldn't do anything but admire him and do what he suggested. He had immense discipline and he expected it from others. I think inwardly it disappointed him that others didn't have the same level of discipline. He knew if you didn't show that sort of discipline off the field, you wouldn't show it on it." Martin Peters recalled: "Ability doesn't happen overnight. I noticed his dedication as the years went on because he would stay after our training at Grange Farm, Chigwell, to do extra work - I was the same: first to arrive and last to leave."

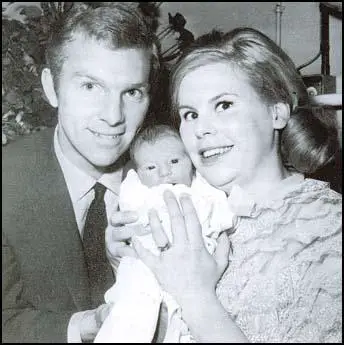

Bobby Moore married Tina in 1962: "I met Bobby just before my 16th birthday. He asked me to dance at the Ilford Palais... I went out with him. From then on, we saw each other more or less six times a week... At that age, he was shy and unsure of himself, but he was a very determined man. He showed that in all aspects of his life... He always put a lot into whatever he did - like our relationship. Every hour he wasn't at football was devoted to us going out. He was wonderful. Very generous, thoughtful and considerate.... At that time Bobby earned about £8 a week and the most you could get was £16 a week, so I wasn't terribly impressed by the fact he was a footballer."

Moore continued to make rapid improvement. Jeff Powell, the author of Bobby Moore: The Life and Times of a Sporting Hero (1997), points out: "Knowing his left foot to be comparatively weak, he spent countless hours perfecting a curved pass with the outside of the right foot to achieve the same effect as a pass with his left. Knowing that he lacked a sharp change of pace, he painstakingly programmed into his make-up a positional sense which made it impossible for opponents to exploit that flaw.... That intense concentration, that search for perfection, was just one of the investments which matured Moore into the best defender in world football."

In his autobiography, Bobby Moore argued: "I look on tackling as a skill. Any time I see a defender just whacking through the back of a forward's legs to get at a ball, that to me is ignorance. You can't win the ball if you've got a body in front of you. You don't have to go around kicking people up in the air to be a good tackler. The art is to deny a forward space and force him to knock the ball away."

1962 World Cup

Ron Greenwood alerted Walter Winterbottom, the England manager, to the rapid progress of his protégé. Winterbottom decided to take Moore to the 1962 World Cup in Chile. The football journalist, Ken Jones, who worked for the Daily Mirror wrote: "'Uncapped, pedestrian, not up to much in the air, suspect stamina. How could England select the 21-year-old Moore for the 1962 World Cup finals?" Moore made his début on 20th May 1962 in England's final pre-tournament friendly against Peru in Lima. England won 4-0 and as Moore pointed out: "Walter was pleased with the defensive performance and kept virtually the same team for all four matches in that World Cup."

The England team got through the group stage but was defeated 3-1 by Brazil in the quarter finals at Viña del Mar. Moore commented: "We came home. Didn't stop to see them win it. I knew they's win it. Stuck four past Chile in the semi and three more past Czechoslovakia in the Final, always having plenty in hand to turn on the magic when they went for the kill in the second-half."

Bobby Moore liked Walter Winterbottom: "He was a warm, outgoing man who loved talking about techniques, tactics, skills, attitudes. You could bet your life he knew every good player in every country by his Christian name, knew every individual's strengths and weaknesses. The man was a walking education on football. But he was at the end of his reign." After Winterbottom resigned after the 1962 World Cup and Alf Ramsey became the new manager.

West Ham finished in a disappointing 12th place in the 1962-63 season. However, Moore continued to impress for England and when Jimmy Armfield was injured, Ramsay made him captain against Czechoslovakia in Bratislava on 29th May 1963. Johnny Haynes was convinced it was the right decision: "He was the obvious choice and nobody else even came close. He was a great user of the ball, which became far more important than it had ever done before. It's important for a captain to be in the right sort of position on the field and he was perfect being in the middle at the back. He was never too loud, but, nevertheless, there was a lot of authority about him."

Ray Wilson later recalled: "I was six years older than him and I wouldn't have wanted the captain's job. Alf made him skipper at 23 and there was no objection, because when Alf made a decision it was usually pretty sound." Moore enjoyed being captain: "I loved that first experience of leading England out. The atmosphere was magic. The crowd are fanatical in Bratislava... The Czechs were still a great side. It had taken Brazil to beat them in the World Cup Final the previous summer and the stars were all there, Popluhar, Novak, the magical man Masopust." England won 4-2 but Armfield returned to the role of captain after recovering from his injury.

Captain of West Ham

Ron Greenwood was slowly building a good team round Bobby Moore. This included Jim Standen, John Bond, Jack Burkett, Ken Brown, Eddie Bovington, Ronnie Boyce, Peter Brabrook, Johnny Byrne, Geoff Hurst, Martin Peters and John Sissons. Greenwood explained: "When I first went to West Ham they employed inside-forwards and wing-halves, but eventually we changed our system to a flat back four to encourage Bobby to play - he was the lynchpin. We set standards because we had players capable of it.... Our full-backs would push up and get forward. In fact, they were more attacking than some present-day wingers... At the back, Bobby could read along the line and cover the whole area. Everyone was tight going forward and Bobby played loose, free, behind everyone else, and the team could go forward with the confidence Bobby was always behind them, reading anything coming through, mopping up. It was a joy to watch him play."

Despite this, West Ham again struggled in the Football League in the 1963-64 season, finishing in 14th place. However, they were much better in the FA Cup and beat Charlton Athletic (3-0), Leyton Orient (3-0), Swindon Town (3-1), Burnley (3-2) and Manchester United (3-1) to get to the final at Wembley Stadium against Preston North End. Moore later recalled: "We were playing against Preston North End, a Second Division side. We'd been magic in the semi-final against Manchester United. Wembley should have belonged to West Ham. We won and it was good to win the first major honour. Apart from that it was a wash-out. We played badly. We spluttered. We didn't fulfill anything we had promised ourselves. Most of us felt let down. We were lucky to beat Preston, and bloody lucky Preston were no better than they were."

The score was 2-2 as the game approached the 90th minute. John Bond pointed out that both sides were extremely tired: "Tiredness and cramp was creeping in for some of the players on the lush Wembley turf. Extra time looked on when Geoff Hurst took the Preston defence on again, stumbled and recovered before sweeping the ball to Peter Brabrook on the right wing. Peter floated a great ball over the Preston defence; and then it all went into slow motion. As the ball floated across, everyone seemed to stop and watch it. Everyone except Ronnie Boyce that is, who came racing in unmarked to head past Kelly."

European Cup Winners' Cup

Bobby Moore had won his first trophy and he was determined that it would be the first of many. As winners of the FA Cup West Ham entered the European Cup Winners' Cup. Played over two legs, victories against La Gantoise (2-1), Sparta Prague (3-2), Lausanne (6-4), Real Zaragoza (3-2) resulted in a final against TSV 1860 München at Wembley Stadium on 19th March, 1965.

West Ham won 2-0 with Alan Sealey scoring both goals. Ron Greenwood, later recalled: "Everything we believed in came true in that match." He added that it was Moore's greatest game under his management. Bobby Moore commented: "We benefited from the experience of the previous year and took part in what many people believe was one of the best matches ever played at the old stadium. There was a lot of good football and we played really well against a good side with a lot of good players."

West Ham's victory made them only the second British club to win a European trophy. Bobby Moore commented: "It was probably one of the greatest nights for a celebration the East End had known since VE Night. In West Ham, Plaistow, Bow, Ilford and Barking the pubs were packed and you could not travel very far without hearing people singing the West Ham national anthem. It was a night to remember all right... Everybody seemed to think it had been one of the finest games of football they had ever seen."

Captain of England

Bobby Moore eventually replaced Jimmy Armfield as England's full-time captain. Alf Ramsey explained: "He (Moore) was already in the England team when I took over as a manager and he was the first player I turned to for a breakdown of his England colleagues. We met in secret, talked our way through 20 players, and at the end of meeting I had decided that this was the man I would entrust with leading England to the glory I felt sure I could bring the country."

Roger Hunt was one of his international colleagues who thought his game had improved under Moore's leadership. "I was classed as an inside-right, but Alf Ramsay changed the formation from wingers to 4-3-3 and 4-4-2, reducing the front men to two, so I became an out and out striker... Basically it bolstered the midfield, you lost an attacker but gained an extra man in midfield and the emphasis was then on the midfield players to get forward. Another reason why it worked was because he (Alf Ramsay) had such good distributors of the ball, like Bobby, who could pick out Geoff Hurst or me at any given moment.... Usually play-makers who can pass like that are in midfield and rarely in the centre of defence. Bobby had been an attacking wing-half with West Ham before he moved into the centre of defence so his passing was as good as anyone's."

George Cohen played in the same English defence as Bobby Moore: "If one of us made a tackle, he was very quick to sweep up any loose ball. He was also very adept at choosing the right moment to close in on an opponent who had taken a poor touch. Winning balls is one thing, but Bob was particularly good at getting his body shape, balance and positioning right after making a tackle, to get himself out of any trouble. Although he might not have been a jumper like big Jack Charlton, he would always make it difficult for an opponent to get a clean head on the ball. If we were under attack, we would funnel the ball out wide, so the danger was not in front of our goal. we would attempt to channel wingers down the outside so we could pin them between the line and reduce their options."

Another member of defence was Nobby Stiles: "Bobby was only a year older than me, but he gave the impression he was much older, like later 20s, early 30s. It was this unique manner he had. You just felt at ease with him and yet, in some ways, you didn't know him. He had an aura, someone you could look up to... We had the best captain in the world. Bobby Moore was a most outstanding centre-back and a most outstanding person." Stiles played just in front of Moore and Jack Charlton, "because neither of them were that quick, my job was to hustle and intercept, but to enable any of the back four to go forward."

Alf Ramsey later argued: "He (Bobby Moore) was my captain and my right-hand man. Bobby was the heartbeat of the England team, the king of the castle, my representative on the field. He made things work on the pitch. I had the deepest trust in him as a man, as a captain, as a confidant.... I could easily overlook his indiscretions, his thirst for the good life, because he was the supreme professional, the best I ever worked with."

At the end of the 1965-66 season Don Revie, the manager of Leeds United, attempted to buy Moore, who wanted to leave the club. Moore, whose contract with West Ham came to an end on 30th June, 1966. Moore, who refused to sign a new contract, went to see Greenwood about the move: "There was no way we could negotiate. West Ham said they would not let me go in any circumstances. Ron and I had it out for hours. Finally we agreed to let it ride until after the World Cup."

1966 World Cup

The 1966 FIFA World Cup was held in Britain. Moore joined the England team for pre-tournament training at the beginning of July. However, under Football Association rules, a non-contracted player could not play for England. When Alf Ramsey heard about this, he ordered Moore back to Upton Park to sign a new contract with West Ham.

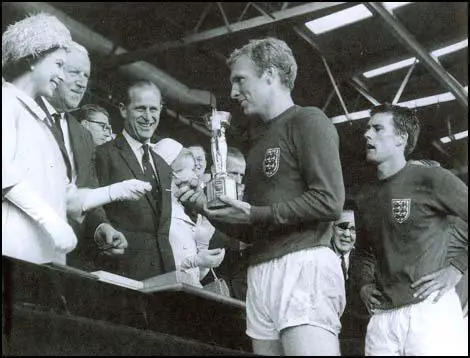

England, captained by Bobby Moore, drew the first game with Uruguay but qualified for the quarter-finals after 2-0 victories against Mexico and France. England played Argentina. According to Martin Peters: "In the quarter-final, Argentina were just hooligans. They didn't want to play, just kick and bite and fight." A headed goal by Geoff Hurst in the 78 minute won the game for England. In the semi-final, England defeated Portugal 2-1 with both goals being scored by Bobby Charlton.

It was feared that Moore would miss the World Cup Final. The England coach, Harold Shepherdson, later revealled: "On the 27th July 1966 he went down with tonsillitis, the day after the semi-final win over Portugal. we were worried it might develop into something worse, but the emergency proved the wisdom of having our own physician on the spot, Dr Alan Bass... It is imperative to get an instant diagnosis, especially in this case, when we had only two full days to get Bobby fit. Dr Bass got cracking right away but if we had left matters for a day, the tonsillitis would have got such a hold on Bobby it would have taken five days to clear up. That is how close Bobby was to missing the final."

Tom Finney, who had recently retired from playing football, was in the crowd for the final against West Germany that was played at Wembley Stadium on 30th July, 1966. "The atmosphere at Wembley that July afternoon was like no other. In the hours leading up to kick-off, long before the dramatic events infolded, the crowd seemed to sense that something special was about to take place."

For the third year in a row, Bobby Moore had the chance of winning a major trophy at the home of British football. Gordon Banks claimed that Moore was a very important figure in the dressing-room before the game going round to everyone, offering words of encouragement. Alf Ramsey told the team: "Gentlemen, you've worked hard for this, we've got this far, now let's get out there and get it won."

In an interview with Jeff Powell, Bobby Moore recalled that England got off to a very bad start: "Helmut Haller gets a goal for the Germans from a bad headed clearance by Ray Wilson. Pride stung because its the first time we've conceded a goal in open play." Nobby Stiles has argued: "We didn't start well and went 1-0 down... but it was Bobby Moore who got us back in the game... He was so far ahead of everyone else in his thinking." Geoff Hurst agreed: "Bobby, fouled by Overath out on the left, quickly took a long, accurate free kick. I knew where he'd put the ball and he knew that I'd be running into that space. It was the sort of thing we'd worked on dozens of times for West Ham. Sure enough, the pass from Bobby was perfection. I ran in from the right, met the ball with my head and steered it past Hans Tilkowski, the German goalkeeper."

It was Bobby Moore's West Ham team-mate, Martin Peters, who put England in the lead: "Geoff Hurst tries a shot from the edge of the box which is blocked and spins into the area. It falls perfect for us in oceans of space in the goalmouth. Martin Peters and Jack Charlton are tanking on to it and Martin wins the race to blast it past two full backs and a goalkeeper, all marooned on the line." Peters later recalled: "I got on the end of a deflection and volleyed it in. It was a tremendous feeling. When I was celebrating I was going back to the half-way line and my fingers were tingling. It was as though a bolt of lightning had gone through me."

England remained in the lead until the 89th minute. Bobby Moore described what happened next: "Out of the blue they get a free kick. Out of nothing, danger. You know the decision should have gone in favour of Jack (Charlton) because the other fellow's backed into him. But there's no percentage in arguing. Only a minute left. Get lined up right. Only a minute left. Deal with this and we're home. Crowded back here. Keep our heads. Here comes the free kick. Make it ours. Someone's trying to clear. Too frantic. The ball hits a body. Schnellinger handles. Come on, ref, bloody handball. No whistle. It spins across the goal. Like running too slow in a nightmare. Everyone heaving and scrambling to get there. Weber scores."

The game now went into extra-time. George Cohen recalled: "The ball comes off the Wembley turf two or three yards faster than a normal pitch because of its spongy nature. It's very wearing and the longer the game went on the more tired the Germans became." Ten minutes into extra-time Nobby Stiles played a long ball to Alan Ball: "I thought I'll never get that, but I managed to outpace Schnellinger and reach it. I knew Geoff liked it delivered early so I whipped it into the near-post space."

Geoff Hurst raced forward to meet Ball's centre: "I made my run a little too soon. This meant that instead of moving on to the ball it was falling slightly behind me. I needed to adjust my body and take a couple of touches to get the ball into a shooting position. To get the power required to strike it properly, I had to fall back. as it turned out I connected beautifully with the ball but, in doing so, toppled over. I therefore had probably the worst view in the ground when the ball struck the underside of the bar and bounced down on the line. My next clear memory is of Roger Hunt, to my left, suddenly halting his forward run and raising an arm in the air. Had there been any doubt about the validity of the goal in Roger's mind, he would have continued his run and supplied the finishing touch."

It has been argued by Chris Lightbown that Tofik Bakramhov, the Russian linesman, was always going to give the goal: "It was known round parts of Europe, but not in England, that Tofik Bakramhov, the linesman had fought the Germans in the war. Did anybody believe that a man who had seen the sort of things he would have seen on the Eastern Front was going to get the Germans off the hook? Once the referee started walking over to consult Bakramhov, the Germans might as well have packed up and gone home."

With England 3-2 up England was expected to play out time, but that was not the way that Moore played the game. As Jack Charlton pointed out: "I was brought up in the north, where defenders took no chances. Bobby Moore was different. In the last seconds of the final, he was in possession on the edge of the box and there were shouts the game was virtually over. Instead of punting it, Bobby had a look upfield... The Germans went to close him down, but Bobby played a casual one-two with little Ballie in the box. Two German players anticipated the move and Bobby ran between them. If he'd lost the ball, we were finished. He moved into the midfield with the ball and I'm still screaming at him to whack it out. It was agonising for me, but he checked, looked up, took all day about it, then delivered a curler of a ball to Geoff."

Alan Ball takes up the story: "When Bobby played that great ball to Geoff... I was running through the middle, square with Geoff, shouting at him to knock it to me. We were two against one and, if he'd passed to me. I could've walked it in." Geoff Hurst recalled in his autobiography, Geoff Hurst: 1966 and All That (2001): "It was the perfect ball. My first thought was not to give it away. We had to keep possession. I sensed that Overath was chasing me as I headed towards the German goal... By this time I was about ten yards outside their box. I can't imagine where I got the strength from to make that run. I was exhausted... I heard Ball calling me. He was chasing hard to support me. It was at this point that I decided to hit the ball with every last ounce of strength." Ball added: "I was about to curse him for being greedy when he hit it but the words stuck in my throat - then I was cartwheeling and yelling with everyone else."

Bobby Charlton believed that Moore's captaincy was a vital ingredient to England's victory: "He was an excellent skipper. He was genuine, a good leader and he linked everyone together. We won the World Cup in 1966 because we were a group, we got on well together and Bobby was our captain." Alf Ramsay went further: "We would not have won the World Cup if Bobby Moore had not been our captain."

West Ham United 1966-1970

Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters returned to West Ham United expecting to have a great season. As well as the three World Cup winners, the team included several talented individuals, Johnny Byrne, Peter Brabrook, Ken Brown, Ronnie Boyce, Harry Redknapp, John Sissons, Jim Standen, Dennis Burnett, Eddie Bovington, Jack Burkett and John Charles. The club also had a manager, Ron Greenwood, who was considered to be one of the best coaches in the country. However, West Ham could only finish in 16th place and were knocked out by Swindon Town in the 3rd Round of the FA Cup. Moore recalled that: "When we got back they had smashed in the windows of my sports shop opposite the ground. I couldn't be angry. It was as hard for us to understand how a team with three World Cup-winning players kept getting it wrong."

In an interview he gave to Jeff Powell, Moore admitted that if "you looked at a few of the individuals and felt there might have been room for improvement." Moore named Jim Standen, Ken Brown and Jack Burkett as players who fell into that category. "If you wanted to be really critical you could find better goalkeepers than Jim Standen... Ken Brown was far from being everyone's ideal at centre half... Jackie Burkett at left back was a very limited player."

Moore was also critical of John Sissons who never developed into the player he thought he could be: "He (Sissons) scored a goal in the FA Cup Final and was still only nineteen when he played in our European Final. At the time he would have been in my squad for the 1966 World Cup. But he never got any better... I'm sure there were many times in those five or six years when Ron made up his mind to leave John out of the side. Then you would see him Monday to Friday in training, up front in the road runs, fastest in the sprints, drilling them into the net with that left foot in five-a-sides, showing you ball skills which demanded a place in the team. Come the Saturday afternoon, nothing. John Sissons was non-existent. He was a thoroughbred who never matured."

Moore thought that a major problem was that Greenwood could not communicate his ideas to most of the West Ham players: "Ron talked about the game at such a high level that sometimes he went straight over the head of the average player... Some days I believe there were only a couple of us who understood a word he was on about. He never seemed to realise that he should have been talking down to more than half the team... Ron needed to work with the best, the elite players."

Ron Greenwood accused Moore of undermining his authority. Greenwood called Moore into his office and complained: "I know you take in what I'm saying, but will you please also look as if you're listening. How else can I make the rest pay attention." Moore told a friend: "Ron asked me why I didn't go to him any more, to ask about the game. He took it as a sign that I was turning against him... Although he respected me, he didn't like me."

Moore claimed that the main reason why he did not talk to Greenwood about the players was because he did not want his team-mates to think he was being disloyal to them: "Perhaps I should have been a go-between. Perhaps it would have helped when things started to go wrong. But I looked on myself as one of thirty professionals, one of the chaps. I didn't want the people I had to play with thinking I was picking the team. Budgie (Byrne) was much closer to Ron, always in and out of his office. But he had a bubbling personality and could get away with it. Nobody would accuse Budgie of getting them dropped."

In his autobiography, Moore argued that: "When we won the two cups Ron had a good team because he had a majority of good players. We could have gone on to dominate the game for a period, the way Leeds did later." Moore complained that Greenwood did not know how to motivate players: "The lads would come in the dressing room with their heads down and he would say we would talk about it on Monday. Why wait? Tell me what I did wrong. Tell another one he can't bloody play. Tell that player he bottled it. He knew, alright. No man never saw so much in a game as Ron Greenwood. But motivation was not his strength. Some games I would love to have done it. Perhaps he wanted me to. But I didn't see it as my job. Not even as captain. It wasn't up to me to slag another player, and God knows I played with enough who weren't good enough."

In 1967 Moore did go to see Greenwood about the team. He argued that the team needed more steel in defence. Moore suggested that the club should sign Maurice Setters: "I begged Ron to sign Maurice. He was tough and could play a bit and we needed to be harder at the back." Greenwood refused claiming that he was "too much of a rebel". Instead, he bought John Cushley from Celtic. Greenwood told Moore, "A nice boy. Been to college".

Cushley was also considered to be a hard player: "Ron knew in his heart that we needed someone to do some kicking... Ron tried to close his eyes to it. In John Cushley he was buying a compromise which satisfied his conscience. A nice lad who could get stuck in... He couldn't expect everyone to be like me and win by intelligence." However, soon after joining West Ham, Greenwood told Cushley after one game: "John, I've bought you to be tough but sometimes you've got to take it easy."Cushley told Moore: "I'm playing it too hard. The manager doesn't like me."

Bobby Moore argues that the same thing happened when Greenwood bought Alan Stephenson from Crystal Palace. Moore heard Greenwood saying to Stephenson: "Alan, you can't get stuck in like that all the time. Sometimes you've got to read it, hold off, use your brain." Moore commented that "Ron was looking for perfection, but it was another centre-half spoiled."

Jeff Powell has argued that Greenwood was right to try to maintain this approach to football: "Those principles guided Greenwood through his coaching and management and won him the respect and admiration of hundreds of people deeply involved in the game. The flowing, open football which Greenwood's beliefs demanded of West Ham also earned him the gratitude of tens of thousands of football-loving spectators who relished watching his team. At times West Ham stood alone against the violence, brutality and intimidation which, in the late Sixties and early Seventies, threatened to bludgeon all the enchantment out of English football."

Ivan Ponting agrees: "Greenwood had been a strong and positive influence on English football throughout his days as a coach and manager. An impeccable sportsman, he deplored the greed and hostility, the cynicism and win-at-all-costs attitude which had become increasingly pervasive. He was a deep thinker and skilled communicator who painted pictures with words on the training ground, believing simplicity was beauty and building his teams from that standpoint. He was no conventional hard man treating players as adults and expecting them to impose their own self-discipline."

Geoff Hurst has suggested that: "The style of play he developed may not have been conducive to the nine-month slog of the league championship race, some of the football West Ham played in his time was the most attractive and memorable in the world. The Upton Park loyalists appreciated the way we played and, most tellingly, came back year after year because they knew they would see a good game of football. West Ham had a well-deserved reputation for high-quality attacking football and Ron was responsible for that."

Hurst conceded that some critics, including Brian Clough, "felt that a West Ham team with Hurst, Moore and Peters should have had greater success." Hurst claims that: "What few understand outside West Ham was that Greenwood cared more about football's finer values than about winning for winning's sake. He was a man of principle and he cared about the sport in a way that many would not understand in the modern game."

In 1967 Greenwood purchased Billy Bonds from Charlton Athletic. Three of the talented local young players, Trevor Brooking, Frank Lampard and Brian Dear had also become regulars in the first team. However, West Ham could only finish in 12th place in the First Division and were knocked out of the FA Cup in the 4th Round against Sheffield United. Greenwood persevered with these youngsters and the following season they finished in 8th place.

It looked like Greenwood was building a team that might recapture the success of the mid-60s. However, the 1969-70 season was a disaster with West Ham only narrowly escaping relegation. They also lost in the 3rd Round of the FA Cup to Middlesbrough. Moore blamed Greenwood for not bringing in the right players. Geoff Hurst was more supportive of Greenwood: "He liked young players with open minds. He challenged them to learn. I took up the challenge them to learn. I took up the challenge. So did others. It was no coincidence that Bobby Moore, Martin Peters and I were among those who flourished in the environment he created at West Ham... Some, of course, ignored the opportunities he presented. There were other talented youngsters at the club, such as Johnny Sissons, Brian Dear and Trevor Dawkins who may have made it to the very top of the profession had they applied themselves more diligently."

By 1970 Martin Peters had given up of winning major honours with West Ham and was transferred to Tottenham Hotspur. As Trevor Brooking pointed out in his autobiography: "When Martin left West Ham in March 1970, the fee of £200,000, which included a valuation of £54,000 for Jimmy Greaves, was a British transfer record. Tottenham gained an international midfield player who was still in his prime whereas West Ham obtained the services of a once-great player who no longer had a zest for the game."

Bobby Moore and Alcohol

Another problem was that Greenwood was unaware of the drinking culture at the club. Bobby Moore, Johnny Byrne, John Cushley, John Charles, Harry Redknapp and Brian Dear were all heavy drinkers. The situation was made even worse with the arrival of Jimmy Greaves in 1970. Trevor Brooking believed that before he left the club, Byrne caused serious problems for Greenwood. "Johnny Byrne was a delightful fellow whom it was impossible to dislike... but he was very undisciplined, particularly when it came to drinking."

Bobby Moore, was one of Byrne's drinking companions. He admitted that Byrne damaged his career with his drinking. "If it hadn't been for the drink aggravating his weight problem Budgie would have been with us in the 1966 World Cup Final." However, Moore felt that his drinking never had an impact on his performance on the pitch. "When I first started out as a young professional I wouldn't dream of taking a drink after Thursday." This changed when Byrne arrived at the club. Moore claimed alcohol helped him unwind but admitted that some West Ham players drank too much: "Ron Greenwood said he felt we were getting a team of nice lads together. I sat and wondered who the hell had ever won anything in football with eleven nice people. But in the next room John Cushley and John Charles, two of the nice boys, were falling off their beds drunk at three in the afternoon."

The problem was that as captain, Bobby Moore was setting a terrible example to the young players at the club. Geoff Hurst pointed out: "He (Greenwood) wanted players to accept responsibility for themselves. But there are risks involved... Players let him down. Some let him down spectacularly, none more so than Bobby Moore." Harry Redknapp admitted much later about the drinking habits of the players: "Did we have some nights out or what? There's a few that I couldn't repeat." After one bad performance the players were banned from going out while in a Stoke hotel. "We used to like going out in Stoke because there were a couple of good clubs, so some of us sneaked out the window at the back of the hotel, ran across the motorway and found some cabs. We had a good time and came back about four in the morning. Climbing over a fence to sneak back in, Bobby slipped and a spike went into his leg... When we got home we had to report back in the afternoon and Bobby turned up saying he had tripped in the garden and landed on a fence. But Bobby was out for three weeks before he landed on a spike while out on the booze in Stoke."

1970 World Cup

The 1970 FIFA World Cup was held in Mexico. England's manager, Alf Ramsey, decided to take a pre-tournament tour of South America. While the English team was in Colombia, Moore was arrested for allegedly stealing a bracelet from a jeweller's shop in the Bogotá. The shop girl, Clara Padilla, claimed to have seen Bobby Moore, near the glass wall cabinet, where the gold bracelet studdied with emeralds, was on show. After the England players had left the shop, Padilla found the bracelet missing.

The prime minister, Harold Wilson, applied pressure on the Colombian authorities and on 29th May 1970, Judge Dorado offered conditional release, subject to Moore signing a declaration that he would make himself available for future questioning at Colombia's consulates in Mexico or London and return to Bogotá if requested. Many years later, The Sunday Times reported that declassified documents "most graded secret or confidential, also show that the embassy was informed almost immediately by the Colombian authorities that Moore had been deliberately set up with the objective of blackmailing him."

England's first game in the 1970 World Cup was against Romania. Despite his recent trouble, Moore had a good game and Geoff Hurst scored the only goal of the game. The next game was against Brazil. According to Jeff Powell, the author of Bobby Moore: The Life and Times of a Sporting Hero (1997):: "By common consent, Bobby Moore produced the paramount performance of his own career, his tackles being captured on film and relayed down the generations as classic examples of the defensive art." Pele claimed: "Bobby Moore is the best defender I have ever played against." However, Moore was unable to stop Jairzinho scoring in the 1-0 victory. At the end of the game Moore and Pele swapped shirts: "I like to think our admiration was mutual because I never resorted to foul tactics against him. It would have been an insult to myself. the way I was brought up to play the game was as a contest of skill and ability and thought."

England qualified for the next stage of the World Cup by beating Czechoslovakia. Their quarter-final opponents were West Germany. The game was played on 14th June. Geoff Hurst pointed out: "The match in prospect was a fascinating one. The Germans had outscored every other nation in the three qualifying matches, Gerd Muller scoring seven of their ten goals. But England had conceded just one goal in three matches and were generally acknowledged to possess the best defence in the world. A key component of the defence was Banks, probably the best goalkeeper in the world."

Gordon Banks, was suffering from gastroenteritis and was replaced at the last moment by Peter Bonetti. England took a 2-0 lead after goals from Alan Mullery and Martin Peters. Moore later commented: "We'd done everything right. The performance was almost as good as against Brazil, and this time we'd got the goals. They had been the only question mark against us until then. The game was won. Done with. Over. England 2-0 up with twenty minutes to go could not be beaten. We'd been proving for years that our defence was unbreakable. No one had put two or three goals past us since 1967."

With England 2-0 up and with the semi-final only three days away, Alf Ramsey decided to take off Bobby Charlton and Martin Peters and replace them with Norman Hunter and Colin Bell. It turned out to be a tragic mistake. Franz Beckenbauer, who had been marked out of the game by Charlton, began to have a strong influence on the game. Bonetti let in a soft shot from Beckenbauer. Moore complained that "when Franz struck the ball it was nothing special" and suggested the Bonetti should have saved it. Geoff Hurst agreed: "It was an unexceptional drive, but it seemed to surprise Peter Bonetti. He dived late and the ball squirmed under his body and into the net."

In the 73rd minute a tired Brian Labone miss-hit a clearance to Karl-Heinz Schnellinger. The West German drove the ball back into the middle and our defence failed to move quickly enough to catch Uwe Seeler offside. Moore believed that once again it was the fault of the England defence: "There was an iffy clearance and not everyone got out quickly enough and Seeler was left deep at the back but still onside. So they lobbed the ball back in. Only hopefully. Really it was too far. On any ordinary day any player in the world would have given it up. but not in a match like that. Uwe did a feat, straining to get his head to the ball. He admitted he had no intention of scoring. He was just trying to keep the ball in play. Yet it flopped over Bonetti into the net. Bonetti's concentration might have been adrift."

West Germany were now the clear favourites to win the game. Moore recalled: "We were doing all we could to stop it but somehow you knew it would come." The German substitute, Juergen Grabowski, was causing terrible problems for the full-back, Terry Cooper. As Geoff Hurst pointed out, "Grabowski's mastery of the shattered Cooper proved decisive. Grabowski crossed, Johannes Loehr headed the ball back into the middle and Muller met it with a thunderous volley past Bonetti who was rooted to his goal line. That was it. England, the holders, were out of the World Cup."

1971 FA Cup Exit

Despite bringing in Jimmy Greaves and Tommy Taylor from Leyton Orient West Ham finished in 20th place in 1970-71 season. West Ham also lost 4-0 to Blackpool in the 3rd Round of the FA Cup. Bobby Moore later recalled: "We were totally outplayed... They were steamed up to have a go and West Ham were never in it. We were left once again with the feeling of utter disappointment at being beaten by a team from lower down the League. Our position in the First Division didn't mean much at the time and everything that season hinged on a good Cup run. But those results had become a regular occurrence."

On the Monday following the game, it was discovered that Bobby Moore, Jimmy Greaves and Brian Dear were out drinking the night before the game. Moore explained: "People will throw up their hands in horror at the thought of professional sportsman going for a drink the night before a game. But it was hardly a diabolical liberty. In fact we thought very little about it. We were in bed by one-thirty and got up about ten o'clock the next morning. That's a good night's sleep by anyone's standards.... The problem was not the drinking. It was the result."

Moore went to see Ron Greenwood about what had happened: "I've come to apologise. We know we did wrong but it wasn't done with any ill intent. All we can do now is apologise." Greenwood replied: "You've hurt me. Let me down. I don't want to talk about it any more. It will be dealt with in due course." The punishment was a two week suspension for Moore, Greaves and Dear, plus a fine of a week's wages, in Moore's case £200.

Moore, who suffered from insomnia, believed he played better after going out for a drink on Friday night than spending several hours tossing and turning in bed. "If you don't have trouble sleeping, you don't know what a hell it can be. Sometimes I'll go downstairs and fall asleep reading. So I'll stir and go back to bed. Then I can't get back to sleep again. There is no way having a drink is worse for me than all that nonsense."

He defended himself against the charge that he was a bad influence on the younger players: "I hope I didn't influence other players, particularly younger players, to drink. I always invited a young player into my company if he was feeling left out of things. If he didn't want to drink that was fine by me. Every individual knows what he's capable of and what's good for him."

Moore continued to try to get a transfer away from West Ham United. In the summer of 1973 Moore was told by Nigel Clarke, who worked for the Daily Mirror, that Brian Clough, the manager of Derby County, wanted to buy him. Moore spoke to Clough on the phone and told him that he was keen on a move to Derby. In September 1973, the West Ham directors agreed a £400,000 bid for Bobby Moore and Trevor Brooking. However, once again, Greenwood blocked the deal. Moore went to see Greenwood: “I had to accept a sort of compromise. If I stayed to help them through that season they would let me go on a free transfer at the end. So I would be able to negotiate a good deal for myself. Transfers are often about luck and timing. It wasn’t long before Cloughie left Derby and Ron was telling me about what a favour he’d done me by stopping me from going up there.”

Moore won his 108th and final cap in the gameagainst Italy on 14th November 1973. At the time he was England's most capped player, beating Bobby Charlton by two appearances, and equalled the record of 90 appearances as captain that Billy Wright had established between 1946 and 1959. Moore's club form also went into decline and he was replaced in the West Ham team by Mick McGiven.

Ron Greenwood was now willing to sell Moore. However, other First Division teams were unwilling to take him. Moore wanted to go to Crystal Palace where Malcolm Allison was the manager. "I believed Malcolm could give me the lift and the appreciation I needed to go on playing well, raise my game again. I wanted Malcolm to tell me where I went wrong and to pat me on the back when I did well. No matter how long you're in the game you need that just like you do when you're a schoolboy."

Signs for Fulham in 1974

However, Allison failed to make an offer and the only serious bid for his services came from Alec Stock, the manager of Fulham, who were in the Second Division. Alan Mullery told him: "Glad you're coming, Bob. You'll love it at Fulham. When I was leaving Tottenham I wanted another First Division club, just like you do. But when I got the opportunity to go back to Fulham I couldn't wait. The atmosphere's different class and all the lads are dying to learn from you. They'll do anything for you."

Moore, who cost £25,000, found it difficult to recapture his form in the Second Division. In his first game for the club, on 19th March, 1974, Fulham suffered a 4-0 home defeat. moore later commented: "We were hammered out of sight. Yet in a way it excited me. Middlesbrough exposed all Fulham's shortcomings in the first night and although the crowd were disappointed, I knew all the information would be invaluable if I was going to make a contribution. I started trying to help out a bit here and there. The lads were so eager to learn and it was lovely watching them mature."

A fre weeks later Fulham played Malcolm Allison's club, Crystal Palace, at Craven Cottage. Moore recalled: "It was Good Friday and Palace came to Fulham and gave us a good hiding, 3-1. I hated it because Malcolm was watching and I wanted to show him what he'd missed in not signing me. My pride was hurt so much that I went off up-field and scored one of my few goals."

Four days later Fulham went to Crystal Palace for the return Easter fixture. They won 2-0, virtually dooming Malcolm Allison to relegation to the Third Division. "There were 30,000 people in Selhurst Park and I always loved a big crowd. On top of that I had a score to settle. I played from the heart and felt great." At the end of the game Allison walked up to Moore and said, "Well done."

1975 FA Cup

Fulham had a much better season the following year. This included a good run in the FA Cup where the beat Hull City, Nottingham Forest, Everton and Carlisle United. In the semi-final Fulham beat Birmingham City with a goal from John Mitchell. Bobby Moore was going back to Wembley Stadium. The great irony was that their opponents were to be West Ham United.

The final took place on 3rd May, 1975. The first-half was goalless but in the 60th minute, Peter Mellor, the Fulham goalkeeper, failed to hold a shot from Billy Jennings and Alan Taylor knocked in the rebound. Five minutes later, Mellor dropped a shot from Graham Paddon and Taylor once again pounced and hit the ball into the roof of the net. Despite the best efforts of Bobby Moore, Fulham were unable to get back in the game.

Moore played for two more seasons for Fulham. His last game was against Blackburn Rovers on 14th May 1977. He then moved to the United States where he played for San Antonio Thunder and Seattle Sounders. In April 1978 he joined Danish side Herning Fremad. It was hoped that the larger crowds would pay for his high wages. This did not materalise and after playing ten games and being paid £24,000 he agreed to cancel his contract with the club.

When Don Revie resigned as manager of England, Bobby Moore wrote to the Football Association about the England managership: "I have gained considerable experience in assisting with coaching both with my clubs in England and abroad during the latter stages of my playing career. I know you are aware of ... how proud I was of my years with the England team." The FA did not even reply.

Football Manager

On 12th December, 1979, Moore was appointed manager of Oxford City in the Isthmian League. Once again he was put on a generous contract. The Oxford chairman, Tony Posser, the owner of a chain of local newspapers, commented: "If Mr. Moore is half as good a manager as he is a negotiator he will do extremely well." Moore failed to achieve success for the club and after being in post for less than a year his contract was cancelled.

In 1984 Moore was appointed manager of Southend United in the Third Division. The club had severe financial problems and was threatened with bankrupcy as well as relegation to the Fourth Division. Moore had some success in the 1985-86 season and were in the promotion race until a poor second-half of the campaign resulted in them finishing in 9th place. In May 1986 Moore resigned as manager.

Bobby Moore, who divorced Tina Moore in 1986, became involved with air-hostess, Stephanie Parlane Moore. The couple married on 4th December 1991. Moore admitted: "There are some things you can't disclose to acquaintances, some things you could never tell a friend... The only person who can do that is the one who cares for you and is deeply involved in the outcome. Stephanie became something deeper, more profound." Stephanie commented: "Bobby epitomised everything I could possibly have wanted. He was my soulmate. He had a tremendous thirst for life and new experiences and he treasured his family above all else."

Journalist

In the 1990s Moore worked as a columinist for the tabloid newspaper, The Sunday Sport and as a football analyst and commentator for Capital Gold. His friend, Jonathan Pearce, who worked with Moore at the radio station, later recalled that he was a very successful interviewer: "Because of the respect Bobby had from everyone, he got some amazing interviews. Bobby did a very good one with Gary Lineker after he was substituted by Graham Taylor in the European Championship and he got the greatest interview I've ever seen with Paul Gascoigne. Gazza was so awe-struck with Mooro he told Bobby stuff he wouldn't tell anyone else."

Death of Bobby Moore

On 22 April 1991 Moore had an "emergency stomach operation" and it was discovered he was suffering from colon cancer. This was kept a secret but after media speculation it was decided on 15th February, 1993 to make a public statement admitting that Moore was suffering from bowel and liver cancer.

Moore commented on the England match against San Marino on 17th February, 1993. The Observer reported: "Moore was a bigger story than what happened on the pitch. The previous day, the world had learnt that he had cancer. The press cameras were trained on Moore, the collar of his leather jacket turned up, his face gaunt and pallid."

Bobby Moore died at his home in Putney seven days later. His funeral was held on 2nd March 1993 at Putney Vale Crematorium, and his ashes were buried in a plot with his father Robert Edward Moore and his mother Doris Joyce Moore.

Primary Sources

(1) Malcolm Allison, Colours of my Life (1975)

Fenton used to pay me £3 extra for training the schoolboys at night. It was then that I found I had a bit of a gift for spotting the boys most likely to make it as professionals. There is one classic example. One intake of youngsters at Upton Park included Bobby Moore - and a boy called Georgie Fenn. Bobby looked a useful prospect. Fenn was considered a certainty to make a really spectacular name for himself. All the big London clubs had gone for him, but he came from an East End family and he chose West Ham. Georgie had scored nine goals in one match for, England boys, and he was also an English schools sprint champion.

After a fortnight of training the boys Fenton called me into his office to ask my opinion of the intake. I said I liked this boy and that, and when I finished he said: "But what about Georgie Fenn?" I said that I didn't give him much of a chance. I didn't like his attitude, he wasn't interested enough. There didn't seem much of a commitment. Fenton threw up his arms and said: "But the kid has so much talent." I said it was a pity but I just couldn't see the Fenn boy making it. At the same time I said that Bobby Moore was going to be a very big player indeed. Everything about his approach was right. He was ready to listen. You could see that already he was seeking perfection.

(2) Geoff Hurst, Geoff Hurst: 1966 and All That (2001)

I remember how impressed I'd been with this blond-haired youngster from Barking when I first started training at West Ham. When we were doing exercises to strengthen the stomach muscles we had to lie on our backs, raise our legs in the air and hold them there. Try it yourself. If you are not used to it you will quickly discover how painful this can be. Of the 50 or so players doing this exercise the last to lower his legs was Bobby Moore. Always.

(3) Noel Cantwell, Moore than a Legend (1997)

Malcolm came out of hospital and trained while Bobby was cruising along in the reserves. Malcolm was ready for the United game but the vacancy was for a left-half. Malcolm was more of a stopper and it needed someone more mobile. When Ted asked me who to pick, it was a hard decision. The sorcerer or his apprentice?

(4) Bobby Moore was interviewed by Jeff Powell, for his book, Bobby Moore: The Life and Times of a Sporting Hero (1993)

Malcolm had been battling for months to recover from tuberculosis. I'd even seen him the day he got the news of his illness. I was a groundstaff boy and I'd gone to Upton Park to collect my wages. I saw Malcolm standing on his own on the balcony at the back of the stand. Tears in his eyes. Big Mal actually crying. He'd been coaching me and coaching me and coaching me but I still didn't feel I knew him well enough to go up and ask what was wrong.

When I came out of the office I looked up again and Noel Cantwell was standing with his arm round Malcolm. He'd just been told he'd got T.B.

It wasn't like Malcolm to give up. By the start of that 1958 season we were battling away together in the reserves, Malcolm proving he could still play, me proving I might be able to play one day.

West Ham had just come up. They went to Portsmouth and won. They beat Wolves at home in their second game. After three or four matches they were top of the First Division, due to play Manchester United on the Monday night, and they had run out of left halves. Billy Lansdowne, Andy Nelson, all of them were unfit. It's got to be me or Malcolm.

I'd been a professional for two and a half months and Malcolm had taught me everything I knew. For all the money in the world I wanted to play. For all the money in the world I wanted Malcolm to play because he'd worked like a bastard for this one game in the First Division.

It would have meant the world to him. Just one more game, just one minute in that game. I knew that on the day Malcolm with all his experience would probably do a better job than me. But maybe I'm one for the future.

It somehow had to be that when I walked into the dressing room and found out I was playing, Malcolm was the first person I saw. I was embarrassed to look at him. He said "Well done. I hope you do well." I knew he meant it but I knew how he felt. For a moment I wanted to push the shirt at him and say "Go on, Malcolm. It's yours. Have your game. I can't stop you. Go on, Malcolm. My time will come."

But he walked out and I thought maybe my time wouldn't come again. Maybe this would be my only chance. I thought: you've got to be lucky to get the chance, and when the chance comes you've got to be good enough to take it.

I went out and played the way Malcolm had always told me to play. Afterwards I looked for him back in the dressing room. Couldn't find him.

(5) James Corbett, The Observer (7th August 2005)

Within six months of Ramsey's appointment, Moore had captained England; and the two east Londoners would form a formidable partnership. Captaining England to World Cup victory in 1966 is what Moore is best remembered for; but his walk to the royal box that July afternoon in 1966 was actually the third time he had collected silverware at Wembley. An FA Cup winner in 1964, and a European Cup-Winners' Cup winner a year later, he had also been named the Football Writers' Association's player of the year in 1964. Yet there is a sense that he under achieved in his domestic career.

He would never finish higher than sixth in the league with West Ham; and although he periodically agitated for a move to Spurs, the West Ham board always insisted on him staying. Finally, in March 1974, he was sold to Fulham. He played in the 1975 FA Cup final when Fulham were beaten 2-0 by his old club, West Ham. When he retired two years later, at the age of 36, he had won 108 England caps (a national record that stood until Peter Shilton broke it in 1989) and made exactly 900 appearances for his two clubs and his country. A distinguished post-playing career seemed inevitable. Only two months after the Watford job fell through, Moore wrote to the Football Association about the England managership, prematurely vacated by Don Revie: "I have gained considerable experience in assisting with coaching both with my clubs in England and abroad during the latter stages of my playing career. I know you are aware of ... how proud I was of my years with the England team." It would have been unprecedented for a newly retired player, no matter how distinguished, to become England manager, and Moore probably didn't expect more than an assistant coaching role. What must have hurt him was that the FA did not even reply.

Moore's first wife, Tina, who now lives in Florida, still expresses disbelief that no club came in with a managerial or coaching offer. 'How could anyone who had Bobby's knowledge and expertise be overlooked in that way?' she asks. 'Kids would have looked up to him and learnt things just by his presence. I can just never ever see to this day why it didn't happen.'

Moore left West Ham on bad terms and was never again fully welcome at the club. The dispute went back to 1966 when he had sought a move to Tottenham; he believed that, with Spurs, he would have a better chance of winning the title. West Ham refused to sell - as the club was entitled to do in the era before freedom of contract - and Moore's determination to go almost prevented him from playing in the World Cup.

When his contract expired on 30 June, he was not only unattached to a club, but unaffiliated to the FA and ineligible to play for the national team. Alf Ramsey had to summon Moore and the West Ham manager, Ron Greenwood, to the England squad's base at Hendon before the two sides agreed to resolve their differences.

The dispute simmered on and, when Greenwood vetoed another transfer to Spurs four years later - which Moore, then 29, saw as his last chance of a big move - the relationship between the two deteriorated further. Finally, Moore was told he could leave on a personally lucrative free transfer at the end of the 1973-74 season.

West Ham reneged even on that promise and sold him to Fulham for £25,000. Although he still held the affection of the fans, Moore never went back to Upton Park, except for work. A friend told me how, driving through east London, Moore gestured towards the ground and said "that's West Ham over there" as if it were somewhere he'd visited once, rather than the scene of so many of his triumphs.