Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler was born in Deerfield, New Hampshire on 5th November, 1818. After graduating from Waterville College in 1838 he became a successful criminal lawyer in Lowell, Massachusetts. As a member of the Democratic Party, Butler served two terms in the state legislature, where he developed a reputation for being sympathetic to the plight of the poor.

Butler supported John Beckenridge against Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election but immediately gave his support to the Union on the outbreak of the American Civil War.

Butler was a brigadier general in the Massachusetts militia and during the Fort Sumter crisis rushed his unit to protect Washington. On 13th May, 1861, Butler used his troops to capture Baltimore. Impressed by his loyalty and initiative, Abraham Lincoln promoted Butler to the rank of major general and sent him to command Fort Monroe in Virginia. Soon afterwards, runaway slaves began to appear at the fort seeking protection. The slaveowners demanded that the runaways should be returned. Butler refused, issuing a statement that he considered the slaves to be "contraband of war".

In the autumn of 1861 Butler was given permission to organize six New England regiments. This led to a conflict with John Andrew, the governor of Massachusetts. As a member of the Republican Party, Andrew was concerned about the number of Democratic Party supporters who were being recruited as officers. Abraham Lincoln supported Butler in this as he was anxious to unite the two parties in defence of the Union.

Butler's army was sent to the Mississippi coast and in May, 1862, they captured New Orleans. Butler was accused of treating Rebels very harshly and after ordering the execution of a man who had torn down the United States flag, he was nicknamed the "beast". Alexander Walker, a pro-Confederate journalist who was one of those arrested, complained that the prisoners were: "closely confined in portable houses and furnished with the most wretched and unwholesome condemned soldiers' rations." He added that some were "compelled to wear a ball and chain, which is never removed."

President Jefferson Davis accused Butler of "inciting African slaves to insurrection" in New Orleans by arming them for war. Davis issued a statement ordering that Butler "no longer be considered or treated simply as a public enemy of the Confederate States of America, but as an outlaw and common enemy of mankind, and that, in the event of his capture, the officer in command of the captured force do cause him to be immediately executed by hanging."

In November, 1863, Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, sent Butler to New York City with 5,000 troops. Stanton feared that during the presidential elections the city might see a return to the Draft Riots that had taken place that summer. The move was successful and the city remained securely under the control of the Union Army.

Abraham Lincoln decided he wanted Butler as his running mate in the 1864 presidential election. It was argued that this would help Lincoln win the votes of the War Democrats. Simon Cameron was sent to talk to Butler about joining the campaign. However, Butler rejected the offer, jokingly saying that he would only accept if Lincoln promised "that within three months after his inauguration he would die".

The American Civil War radicalized Butler. He became a strong opponent of slavery and refused to return fugitive slaves. He was also one of the few military commanders who favoured the recruitment of black regiments. He established a unit of African American soldiers called the First Regiment Louisiana Native Guards. In December, 1864, he united thirty-seven black regiments to form the Twenty-Fifth Corps. He also arranged for these soldiers to be taught to read and write. These actions made him very popular with the Radical Republicans in Congress.

General Ulysses S. Grant had doubts about Butler's abilities as a military commander and was very disappointed with his unsuccessful operations against Richmond and Petersburg. When Butler failed to capture Wilmington, North Carolina, in December, 1864, Grant and Lincoln decided to relieve Butler of his command.

After the war Butler joined the Republican Party and was elected to the 40th Congress. Butler soon associated himself with the group that became known as the Radical Republicans. Butler opposed the policies of President Andrew Johnson and argued in Congress that Southern plantations should be taken from their owners and divided among the former slaves. He also attacked Johnson when he attempted to veto the extension of the Freeman's Bureau, the Civil Rights Bill and the Reconstruction Acts.

In 1867 Butler joined with Benjamin Loan and James Ashley in claiming that Andrew Johnson had been involved in the conspiracy to murder Abraham Lincoln. Butler asked the question: "Who it was that could profit by assassination (of Lincoln) who could not profit by capture and abduction? He followed this with: "Who it was expected by the conspirators would succeed to Lincoln, if the knife made a vacancy?" He also implied that Johnson had been involved in tampering with the diary of John Wilkes Booth. "Who spoliated that book? Who suppressed that evidence?"

In November, 1867, the Judiciary Committee voted 5-4 that Andrew Johnson be impeached by high crimes and misdemeanors. The majority report written by Thomas Williams contained a series of charges including pardoning traitors, profiting from the illegal disposal of railroads in Tennessee, defying Congress, denying the right to reconstruct the South and attempts to prevent the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment.

On 30th March, 1868, Johnson's impeachment trial began. Johnson was the first and only president of the United States to be impeached. The trial, held in the Senate in March, was presided over by Chief Justice Salmon Chase. During the trial Butler was one of Johnson's fiercest critics.

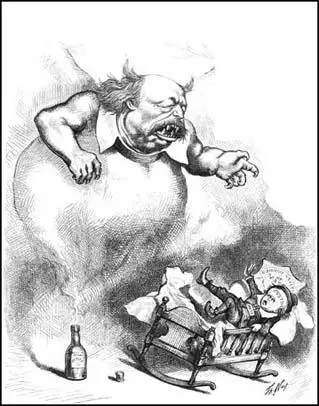

Danger, Harper's Weekly (11th April, 1872)

Although a large number of senators believed that Johnson was guilty of the charges, they disliked the idea of Benjamin Wade becoming the next president. Wade, who believed in women's suffrage and trade union rights, was considered by many members of the Republican Party as being an extreme radical. James Garfield warned that Wade was "a man of violent passions, extreme opinions and narrow views who was surrounded by the worst and most violent elements in the Republican Party." Others Republicans such as James Grimes argued that Johnson had less than a year left in office and that they were willing to vote against impeachment if Johnson was willing to provide some guarantees that he would not continue to interfere with Reconstruction.

When the vote was taken all members of the Democratic Party voted against impeachment. So also did those Republicans such as Lyman Trumbull, William Fessenden and James Grimes, who disliked the idea of Benjamin Wade becoming president. The result was 35 to 19, one vote short of the required two-thirds majority for conviction. A further vote on 26th May, also failed to get the necessary majority needed to impeach Johnson. The Radical Republicans were angry that not all the Republican Party voted for a conviction and Butler claimed that Johnson had bribed two of the senators who switched their votes at the last moment.

Butler became very concerned about the activities of the Ku Klux Klan in the Deep South. He urged President Ulysses S. Grant to take action and in 1870 he instigated an investigation into the organization and the following year a Grand Jury reported that: "There has existed since 1868, in many counties of the state, an organization known as the Ku Klux Klan, or Invisible Empire of the South, which embraces in its membership a large proportion of the white population of every profession and class. The Klan has a constitution and bylaws, which provides, among other things, that each member shall furnish himself with a pistol, a Ku Klux gown and a signal instrument. The operations of the Klan are executed in the night and are invariably directed against members of the Republican Party. The Klan is inflicting summary vengeance on the colored citizens of these citizens by breaking into their houses at the dead of night, dragging them from their beds, torturing them in the most inhuman manner, and in many instances murdering."

Congress passed the Ku Klux Act and became law on 20th April, 1871. This gave the president the power to intervene in troubled states with the authority to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in countries where disturbances occurred. Although Ulysses S. Grant used this legislation several times, the Ku Klux Klan was not destroyed.

Butler was reelected to Congress four times and served from March, 1867 to March, 1875 and March, 1877 to March, 1879. Chairman of the Committee on Revision of the Laws, Butler played a leading role in the passing of the Civil Rights Act (1875).

Disillusioned with the Republican Party Butler rejoined the Democratic Party and in 1882 he was elected as Governor of Massachusetts. Two years later he became the presidential candidate of the Greenback-Labor Party and the Anti-Monopoly Party. His program included plans for graduated income tax, the direct election of Senators, the establishment of a Department of Labor, and financial assistance to farmers. However, at the polls he was easily defeated by Grover Cleveland.

Butler's memoirs, Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences, was published in 1892. Benjamin Franklin Butler died in Washington on 11th January, 1893. Butler's grand daughter, Blanche Ames, was a leading activist in the struggle for woman's suffrage.

Primary Sources

(1) Benjamin F. Butler, report published on 30th July, 1861.

In the village of Hampton there were a large number of Negroes, composed in a great measure of women and children of the men who had fled thither within my lines for protection, who had escaped from marauding parties of rebels who had been gathering up able-bodied blacks to aid them in constructing their batteries on the James and York rivers. I have employed the men in Hampton in throwing up entrenchments, and they were working zealously and efficiently at that duty, saving our soldiers from the labor under the gleam of the midday sun.

I have seen it stated that an order had been issued by General McDowell, in his department, substantially forbidding all fugitive slaves from coming within his lines or being harbored there. Is that order to be enforced in all military departments? If so, who are to be considered fugitive slaves? Is a slave to be considered fugitive whose master runs away and leaves him? Is it forbidden to the troops to aid or harbor within the lines the Negro children who are found therein, or is the soldier, when his march has destroyed their means of subsistence, to allow them to starve because he has driven off the Rebel masters?

In a loyal state, I would put down a service insurrection. In a state of rebellion. I would confiscate that which was used to oppose my arms, and take all the property which constituted the wealth of that state and furnished the means by which the war is prosecuted, besides being the cause of the war; and if, in so doing, it should be objected that human beings were bought to the free enjoyment of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, such objection might not require much consideration.

(2) Alexander Walker, a journalist, was arrested and sent to Ship Island, Mississippi, when he complained about Benjamin F. Butler after he occupied New Orleans (13th September, 1862)

Previous to my committal to Ship Island as a close prisoner, where I was consigned with seven other respectable citizens to a small hut, fifteen feet by twenty, exposed to rain and sun, without permission to leave except for a bath in the sea once or twice a week, I had prepared an elaborate statement of the outrages perpetrated by Butler upon our people.

A description of the causes and circumstances of the imprisonment of our citizens who are now held on this island will afford some of the mildest illustrations of Butler's brutality. There are about sixty prisoners here, all of whom are closely confined in portable houses and furnished with the most wretched and unwholesome condemned soldiers' rations. Some are kept at hard labor on the fort; several, in addition to labor, are compelled to wear a ball and chain, which is never removed.

(3) Benjamin F. Butler, statement about the occupation of New Orleans (24th December, 1862)

I saw that this Rebellion was a war of the aristocrats against the middling men, of the rich against the poor; a war of the land-owner against the laborer; that it was a struggle for the retention of power in the hands of the few against the many; and I found no conclusion to it, save in the subjugation of the few and the disenthrallment of the many. I therefore felt no hesitation in taking the substance of the wealthy, who had caused the war, to feed the innocent poor, who had suffered by the war.

(4) President Jefferson Davis, statement about the occupation of New Orleans (December, 1862)

Repeated pretexts have been sought or invented for plundering the inhabitants of a captured city, by fines levied and collected under threats of imprisoning recusants at hard labor with ball and chain. The entire population of New Orleans have been forced to elect between starvation by the confiscation of all their property and taking an oath against conscience to bear allegiance to the invader of their country.

The African slaves have not only been incited to insurrection by every license and encouragement, but numbers of them have actually been armed for a servile war - a war in its nature far exceeding the horrors and most merciless atrocities of savages. Officers under Benjamin F. Butler have been in many instances, active and zealous agents in the commission of these crimes, and no instance is known of the refusal of any one of them to participate in the outrages.

I, Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America, and in their name, do pronounce and declare the said Benjamin F. Butler to be a felon, deserving of capital punishment. I do order that he shall no longer be considered or treated simply as a public enemy of the Confederate States of America, but as an outlaw and common enemy of mankind, and that, in the event of his capture, the officer in command of the captured force do cause him to be immediately executed by hanging.

(5) Benjamin F. Butler, Autobiography and Reminiscences (1892)

In the spring of 1863, I had another conversation with President Lincoln upon the subject of the employment of negroes. The question was, whether all the negro troops then enlisted and organized should be collected together and made a part of the Army of the Potomac and thus reinforce it.

We then talked of a favourite project he had of getting rid of the negroes by colonization, and he asked me what I thought of it. I told him that it was simply impossible; that the negroes would not go away, for they loved their homes as much as the rest of us, and all efforts at colonization would not make a substantial impression upon the number of negroes in the country.

Reverting to the subject of arming the negroes, I said to him that it might be possible to start with a sufficient army of white troops, and, avoiding a march which might deplete their ranks by death and sickness, to take in ships and land them somewhere on the Southern coast. These troops could then come up through the Confederacy, gathering up negroes, who could be armed at first with arms that they could handle, so as to defend themselves and aid the rest of the army in case of rebel charges upon it. In this way we could establish ourselves down there with an army that would be a terror to the whole South.

Our conversation then turned upon another subject which had been frequently a source of discussion between us, and that was the effect of his clemency in not having deserters speedily and universally punished by death.

I called his attention to the fact that the great bounties then being offered were such a temptation for a man to desert in order to get home and enlist in another corps where he would be safe from punishment, that the army was being continually depleted at the front even if replenished at the rear.

He answered with a sorrowful face, which always came over him when he discussed this topic: "But I can't do that, General." "Well, then," I replied, "I would throw the responsibility upon the general-in-chief and relieve myself of of it personally."

With a still deeper shade of sorrow he answered: "The responsibility would be mine, all the same."

(6) Benjamin F. Butler met Ulysses S. Grant for the first time in April, 1864.

Lieutenant-General Grant visited Fortress Monroe on the 1st April. To him the state of the negotiations as to exchange of prisoners was communicated, and most emphatic verbal directions were received from the lieutenant-general not to take any steps by which another able-bodied man should be exchanged until further orders from him.

He then explained to me his views upon these matters. He said that I would agree with him that by the exchange of prisoners we get no men fit to go into our army, and every soldier we gave the Confederates went immediately into theirs, so that the exchange was virtually so much aid to them and none to us. For we gave them well men who went directly into their ranks and we had but few others, as the returns showed. Yet we received none from them substantially but disabled men, and by our laws and regulations they were to be allowed to go home and recuperate, which few of them did, and fewer still came back to our armies.

Now, the coming campaign was to be decided by the strength of the opposing forces, for the contest would all centre upon the Army of the Potomac and its immediate adjuncts. His proposition was to make an aggressive fight upon Lee, trusting to the superiority of numbers and to the practical impossibility of Lee getting any considerable reinforcements to keep up his army. We had twenty-six thousand Confederate prisoners, and if they were exchanged it would give the Confederates a corps, larger than any in Lee's army, of disciplined veterans better able to stand the hardships of a campaign and more capable than any other. To continue exchanging upon parole the prisoners captured on one side and the other, especially if we captured more prisoners than they did, would at least add from thirty to perhaps fifty per cent to Lee's capability for resistance.

(7) In 1864 Abraham Lincoln sent Simon Cameron to see Benjamin F. Butler at Fortress Monroe.

Simon Cameron, who stood very high in Mr. Lincoln's confidence, came to see me at Fortress Monroe. He spoke with directness. "The President, as you know, intends to be a candidate for re-election, and as his friends indicate that Mr. Hamlin should no longer be a candidate for Vice-President, and as he is from New England, the President thinks his place should be filled by someone from that section. Besides reasons of personal friendship which would be pleasant to have you with him, he believes that as you were the first prominent Democrat who volunteered for the war, your candidate would add strength to the ticket, especially with the War Democrats, and he hopes that you will allow your friends to co-operate with his to place you in that position."

"Please say to Mr. Lincoln," I replied, "that while I appreciate with the fullest sensibilities his act of friendship and the high compliment he pays me, yet I must decline. Tell him that I said laughingly that with the prospects of a campaign before me I would not quit the field to be Vice-President even with himself as President, unless he would give me bond in sureties in the full sum of his four years' salary that within three months after his inauguration he will die unresigned.

(8) Benjamin F. Butler, speech in Congress about the diary of John Wilkes Booth (1867)

That diary, as now produced, had eighteen pages cut out, the pages prior to the time when Abraham Lincoln was massacred, although the edges as yet show they had all been written over. Now, what I want to know, was that diary whole? Who spoliated that book?

(9) Benjamin Butler, Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences (1892)

Andrew Johnson had been suspected by many people of being concerned in the plans of Booth against the life of Lincoln or at least cognizant of them. A committee of which I was the head, felt it their duty to make a secret investigation of that matter, and we did our duty in that regard most thoroughly. Speaking for myself I think I ought to say that there was no reliable evidence at all to convince a prudent and responsible man that there was any ground for the suspicions entertained against Johnson.

(10) In his autobiography, Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences, Benjamin F. Butler wrote about the passing of legislation against the Ku Klux Klan in 1870.

There were numerous large bands of organized marauders called the Ku Klux Klan, who were dressed in fantastic uniforms, and who rode at night and inflicted unnumbered and horrible outrages upon the negro so that he could not dare to come to the polls. Indeed, the men of the South seemed to think themselves excused in these outrages because they wanted to insure a white man's government in their States.

I desired that Congress should pass laws, which, with their punishments and modes of execution, would be sufficiently severe under the circumstances to prevent those outrages entirely, or at least to punish them.

A bill was reported by that special committee. By the bill this murdering of negroes of Ku Klux riders at night was to be deemed conspiracy, and punished by fine and imprisonment. But the prisoner would first have to be convicted by a Southern jury, and upon these juries other members of the Ku Klux could serve if their own cases were not on trial. That bill was passed, and the government made great show of enforcing it.