Richard Carlile

Richard Carlile, the son of a shoemaker from Ashburton, was born on 8th December, 1790. Richard's father abandoned the family in 1794 and it was a struggle for his mother to look after her three children from the profits of the small shop that she ran in the town. Richard received six years free education from the local Church of England school and learnt to read and write. (1)

At the age of twelve Carlile left school and was apprenticed as a tinplateman in Plymouth. In 1813 he married a local woman and soon afterwards the couple moved to London. Over the next few years Jane Carlile gave birth to five children, three of whom survived.

Richard found work as a tinsmith but in the winter of 1816, Carlile had his hours reduced by his employer. Short-time work created serious economic problems for the Carlile family. For the first time in his life, Carlile began attending political meetings. At these meetings Carlile heard speakers like Henry Hunt complain bitterly about a parliamentary system that only allowed three men in every hundred to vote. (2)

Carlile later wrote that as a young man he had the ambition to get my living by the pen, as more respectable and less laborious than working fourteen, sixteen and eighteen hours per day for a very humble living... I shared in the general distress of 1816, and it was this that opened my eyes. Having my attention drawn to politics, I began to read everything I could get at upon the subject with avidity, and I soon saw what was the importance of a free press." (3)

Carlile found the arguments for reform convincing and began to wonder why it had taken him so long to realize that the system was unfair. As a young boy, Carlile remembered taking part in ceremonies where an effigy of Tom Paine was burnt at the stake. Carlile, like the rest of the people living in his village had believed the local vicar when he told them that Paine was an evil man for suggesting the need for parliamentary reform.

In 1817 he became a hawker of pamphlets and journals. The same year he met William Sherwin, who had just started Sherwin's Political Register, and they entered into a business arrangement whereby he became the journal's publisher. He also became the author of several pamphlets. Carlile tried to earn a living by selling the writings of parliamentary reformers on the streets of London. Later Carlile was to comment that he often walked "thirty miles for a profit of eighteen pence".

Richard Carlile: Newspaper Publisher

Carlile decided to rent a shop in Fleet Street and become a publisher. Instead of publishing works such as Paine's The Rights of Man and the Principles of Government in book form, Carlile divided them into sections and then sold them as small pamphlets. In August 1817, he reprinted the political parodies of William Hone and was imprisoned awaiting trial on charges of seditious libel and blasphemy. He remained there for four months until the charges were dropped on Hone's famous acquittal. (4)

Carlile was convinced that the printing press had the power to change society. "The printing press has become the Universal Monarch and the Republic of Letters will go to abolish all minor monarchies, and give freedom to the whole human race by making it as one nation and one family." He thought this was so important that he was willing to go to prison for his beliefs. (5)

During this period he developed the reputation as the most successful popularizer of Paine since the 1790s. This included the publication of Age of Reason, a book that was extremely critical of the Church of England and had been immediately banned when it initially appeared in 1797. Under the seditious libel laws, it was offence to publish material that might encourage people to hate the government and he was the subject of several prosecutions, throughout which he continued to publish despite intermittent spells in prison.

Peterloo Massacre

In March 1819, Joseph Johnson, John Knight and James Wroe formed the Manchester Patriotic Union Society. All the leading radicals in Manchester joined the organisation. Johnson was appointed secretary and Wroe became treasurer. The main objective of this new organisation was to obtain parliamentary reform and during the summer of 1819 it was decided to invite Richard Carlile, Major John Cartwright, and Henry Orator Hunt to speak at a public meeting in Manchester. The men were told that this was to be "a meeting of the county of Lancashire, than of Manchester alone. I think by good management the largest assembly may be procured that was ever seen in this country." Cartwright was unable to attend but Hunt and Carlile agreed and the meeting was arranged to take place at St. Peter's Field on 16th August. (6)

At about 11.00 a.m. on 16th August, 1819 William Hulton, the chairman, and nine other magistrates met at Mr. Buxton's house in Mount Street that overlooked St. Peter's Field. Although there was no trouble the magistrates became concerned by the growing size of the crowd. Estimations concerning the size of the crowd vary but Hulton came to the conclusion that there were at least 50,000 people in St. Peter's Field by midday. Hulton therefore took the decision to send Edward Clayton, the Boroughreeve and the special constables to clear a path through the crowd. The 400 special constables were therefore ordered to form two continuous lines between the hustings where the speeches were to take place, and Mr. Buxton's house where the magistrates were staying. (7)

The main speakers at the meeting arrived at 1.20 p.m. This included Richard Carlile, Henry 'Orator' Hunt, John Knight, Joseph Johnson and Mary Fildes. Several of the newspaper reporters, including John Tyas of The Times, Edward Baines of the Leeds Mercury, John Smith of the Liverpool Mercury and John Saxton of the Manchester Observer, joined the speakers on the hustings.

At 1.30 p.m. the magistrates came to the conclusion that "the town was in great danger". William Hulton therefore decided to instruct Joseph Nadin, Deputy Constable of Manchester, to arrest Richard Carlile and the other proposed speakers. Nadin replied that this could not be done without the help of the military. Hulton then wrote two letters and sent them to Lieutenant Colonel L'Estrange, the commander of the military forces in Manchester and Major Thomas Trafford, the commander of the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry.

When Captain Hugh Birley and his men reached the hustings they arrested most of the men. As well as the speakers and the organisers of the meeting, Birley also arrested the newspaper reporters on the hustings. John Edward Taylor reported: "A comparatively undisciplined body, led on by officers who had never had any experience in military affairs, and probably all under the influence both of personal fear and considerable political feeling of hostility, could not be expected to act either with coolness or discrimination; and accordingly, men, women, and children, constables, and Reformers, were equally exposed to their attacks." (8)

Samuel Bamford was another one in the crowd who witnessed the attack on the crowd: "The cavalry were in confusion; they evidently could not, with the weight of man and horse, penetrate that compact mass of human beings; and their sabres were plied to cut a way through naked held-up hands and defenceless heads... On the breaking of the crowd the yeomanry wheeled, and, dashing whenever there was an opening, they followed, pressing and wounding. Women and tender youths were indiscriminately sabred or trampled... A young married woman of our party, with her face all bloody, her hair streaming about her, her bonnet hanging by the string, and her apron weighed with stones, kept her assailant at bay until she fell backwards and was near being taken; but she got away covered with severe bruises. In ten minutes from the commencement of the havoc the field was an open and almost deserted space. The hustings remained, with a few broken and hewed flag-staves erect, and a torn and gashed banner or two dropping; whilst over the whole field were strewed caps, bonnets, hats, shawls, and shoes, and other parts of male and female dress, trampled, torn, and bloody. Several mounds of human flesh still remained where they had fallen, crushed down and smothered. Some of these still groaning, others with staring eyes, were gasping for breath, and others would never breathe again." (9)

Lieutenant Colonel L'Estrange reported to William Hulton at 1.50 p.m. When he asked Hulton what was happening he replied: "Good God, Sir, don't you see they are attacking the Yeomanry? Disperse them." L'Estrange now ordered Lieutenant Jolliffe and the 15th Hussars to rescue the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry. By 2.00 p.m. the soldiers had cleared most of the crowd from St. Peter's Field. In the process, 18 people were killed and about 500, including 100 women, were wounded. (10)

Richard Carlile managed to avoid being arrested and after being hidden by local radicals, he took the first mail coach to London. The following day placards for Sherwin's Political Register began appearing in London with the words: 'Horrid Massacres at Manchester'. A full report of the meeting appeared in the next edition of the newspaper. The authorities responded by raiding Carlile's shop in Fleet Street and confiscating his complete stock of newspapers and pamphlets. (11)

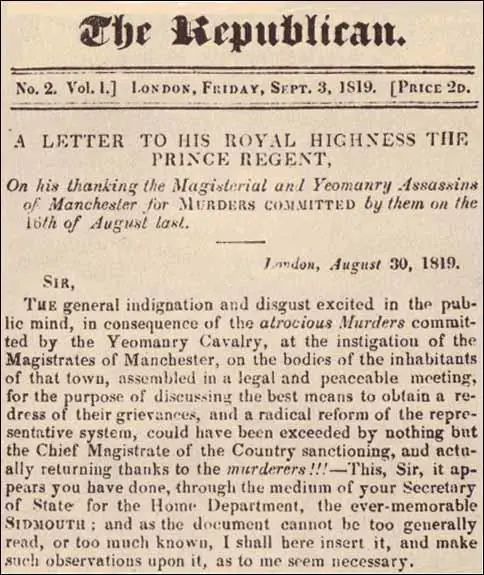

The Republican

Carlile now decided to change his newspaper's name to The Republican. In the first edition he wrote about the Peterloo Massacre: "The massacre of the unoffending inhabitants of Manchester, on the 16th of August, by the Yeomanry Cavalry and Police at the instigation of the Magistrates, should be the daily theme of the Press until the murderers are brought to justice. Captain Nadin and his banditti of police, are hourly engaged to plunder and ill-use the peaceable inhabitants; whilst every appeal from those repeated assaults to the Magistrates for redress, is treated by them with derision and insult. Every man in Manchester who avows his opinions on the necessity of reform, should never go unarmed - retaliation has become a duty, and revenge an act of justice." (12)

Carlile not only described how the military had charged the crowd but also criticised the government for its role in the incident. Under the seditious libel laws, it was offence to publish material that might encourage people to hate the government. The authorities also disapproved of Carlile publishing books by Tom Paine, including Age of Reason, a book that was extremely critical of the Church of England. In October 1819, Carlile was found guilty of blasphemy and seditious libel and was sentenced to six years in Dorchester Gaol. (13)

Carlile was also fined £1,500 and when he refused to pay, his Fleet Street offices were raided and his stock was confiscated. Carlile was determined not to be silenced. While he was in prison he continued to write material for The Republican, which was now being published by his wife. Due to the publicity created by Carlile's trial, the circulation of the newspaper increased dramatically and was now outselling pro-government newspapers such as The Times. (14)

The government was greatly concerned by the dangers of the parliamentary reform movement and Lord Sidmouth, the Home Secretary, wrote a letter to Lord Liverpool, the Prime Minister, arguing that the government needed to take firm action. This was supported by John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon, the Lord Chancellor, who was of the clear opinion that the Peterloo meeting "was an overt act of treason". (15)

As Terry Eagleton has pointed out the "liberal state is neutral between capitalism and its critics until the critics look like they're winning." (16) When Parliament reassembled on 23rd November, 1819, Sidmouth announced details of what later became known as the Six Acts. The main objective of this legislation was the "curbing radical journals and meeting as well as the danger of armed insurrection". (17)

This included: (v) The Basphemous and Seditious Libels Act: A measure which provided much stronger punishments, including banishment for publications judged to be blasphemous or seditious. (vi) Newspaper and Stamp Duties Act: A measure which subjected certain radical publications which had previously avoided stamp duty by publishing opinion and not news, to such duty. The government imposed a 4d. tax on cheap newspapers and stipulating that they could not be sold for less than 7d. As most working people were earning less than 10 shillings a week, this severely reduced the number of people who could afford to buy radical newspapers.

A Stamp Tax had been first imposed on British newspapers in 1712. The tax was gradually increased until in 1815 it had reached 4d. a copy. As few people could afford to pay 6d. or 7d. for a newspaper, the tax restricted the circulation of most of these journals to people with fairly high incomes. During this period most working people were earning less than 10 shillings a week and this therefore severely reduced the number of people who could afford to buy radical newspapers.

Campaigners against the stamp tax such as William Cobbett and Leigh Hunt described it as a "tax on knowledge". As Richard Carlile pointed out: "Let us then endeavor to progress in knowledge, since knowledge is demonstrably proved to be power. It is the power knowledge that checks the crimes of cabinets and courts; it is the power of knowledge that must put a stop to bloody wars." (18)

Carlile spent most of his six years in prison in isolation. With the help of his family and friends Carlile was able to continue publishing The Republican. In 1820, to avoid Stamp Duty, Carlile put up the price of the newspaper to sixpence. (19) Despite this move, people were still prosecuted for being involved in the publication of the newspaper. This included in the imprisonment of his wife, Jane Carlile (February 1821) and his sister, Mary-Anne Carlile (June 1822) for two years each. Jane was actually imprisoned with her husband and she gave birth to a daughter, Hypatia in June 1822. (20)

These newspapers had no problems finding people willing to sell these newspapers. Joseph Swann had sold Carlile's pamphlets and newspapers in Macclesfield since 1819. He was arrested and in court he was asked if he had anything to say in his defence: "Well, sir, I have been out of employment for some time; neither can I obtain work; my family are all starving... And for another reason, the weightiest of all; I sell them for the good of my fellow countrymen; to let them see how they are misrepresented in parliament... I wish every man to read those publications." The judge responded by sentencing him to three months hard labour. (21)

It has been argued that the significance of Carlile's achievement lies in his contribution to the cause of free speech and a free press. "His publishing career and his championship of the oppressed, of no advantage to himself or his family, stand as testimony to the depth of commitment to be found in the artisan class of the early nineteenth century. Carlile never gave up, never became disaffected, and continuously sought to discover new opportunities of disseminating his conviction that freedom from the shackles of orthodoxy and oppression was essential for the future of his civilization". (22)

Susannah Wright was a Nottingham lace-mender, who sold Carlile's newspapers and pamphlets. She appeared in court in November 1822 with her six-month old baby. The New Times reported that "this wretched and shameless woman" was an "abandoned creature who has cast off all the distinctive shame and fear and decency of her sex" and was a "horrid example" of a woman who gave support to the publication of "gross, vulgar, horrid blasphemy." (23)

In court Susannah Wright argued that "a representative system of government would soon see the propriety of turning our churches and chapels into temples of science... cherishing the philosopher instead of the priest... As the blood of the Christian Martyrs become the seed of the Christian Church, so shall our sufferings become the seed of free discussion, and in those very sufferings we will triumph over you." (24) After her long speech she "was applauded and loudly cheered" before being sent to Newgate Prison. (25) It has been calculated that around 150 vendors and shopmen served over 200 years of imprisonment in the struggle for a free press. (26)

Richard Carlile believed strongly in the educative possibilities of prison. In his letters to other imprisoned radicals he urged them to use the opportunity presented by their prison sentences to further their education. (27) "We should have more philosophers in our gaols than debtors, smugglers or poachers". (28) George Holyoake later argued that Carlile did not trust any man unless he had been imprisoned for his beliefs. (29)

Birth Control and Child Labour

When Richard Carlile was released from prison in November 1825 he returned to publishing newspapers. In The Republican he argued: "My long confinement was, in fact, a sort of penal representation for the whole. I confess that I have touched extremes that many thought imprudent, and which I would only see to be useful with a view of habiting the Government and people to all extremes of discussion so as to remove all ideas of impropriety from the media which were most useful. If I find that I have done this I shall become a most happy man; if not, I have the same disposition unimpaired with which I began my present career-a disposition to suffer fines, imprisonment or banishment, rather than that any man shall hold the power and exercise the audacity to say, and to act upon it, that any kind of discussion is improper and publicly injurious." (30)

The people who worked in Carlile's shop were also persecuted. The authorities used agents to buy newspapers and pamphlets and then gave evidence against them in court. He therefore devised a system that became known as the "invisible shopman". Instead of a counter, the shop used a partition in the middle of which an indicator could be pointed to the names of works arranged around a dial. Customers turned the finger to the book they needed, put their money in a slot, and the book dropped to them along a chute." (31)

Carlile was now a strong supporter of women's rights. He argued that "equality between the sexes" should be the objective of all reformers. Carlile wrote articles in his newspapers suggesting that women should have the right to vote and be elected to Parliament. Carlile pointed out: "I do not like the doctrine of women keeping at home, and minding the house and the family. It is as much the proper business of the man as the woman; and the woman, who is so confined, is not the proper companion of the public useful man". (32)

In 1826 Carlile published Every Woman's Book, a book "which argued for a rational approach to birth control, attacking the Christian demonization of sexual desire while denying the traditional chauvinist assumptions about women". It was "an important contribution to the nineteenth-century debate on birth control" but the book "damaged his support among radicals and the disaffected working class". (33)

The Republican, which ceased publication in December 1826 as a consequence of a dwindling circulation. In his writings Carlile abandoned his stance as a rationalist and began to call himself a "Christian atheist". In early 1827 Carlile embarked on the first of a series of lecture tours in the southern provinces, and in July he set off for six months in the north. Christina Parolin has argued: "Though prison had developed him as a scholar... Carlile was a poor public speaker and lacked the charisma, showmanship and oratorical skills to sustain audiences." (34)

Carlile was involved in the campaign against child labour in factories. In 1827 Carlile was given a copy of manuscript written by John Brown, a radical journalist from Bolton. Brown's manuscript was based on an interview with a former parish apprentice called Robert Blincoe. Carlile published Robert Blincoe's Memoir in his new newspaper, The Lion. Robert Blincoe's story appeared in five weekly episodes from 25th January to 22nd February, 1828.

In his introduction Carlile argued: "John Brown is now dead; he fell, about two or three years ago, by his own hand. He united, with a strong feeling for the injuries and sufferings of others. Hence his suicide. Had he not possessed a fine fellow-feeling with the child of misfortune, he would never have taken such pains to compile the Memoir of Robert Blincoe, and to collect all the wrongs on paper, on which he could gain information, about the various sufferers under the cotton-mill systems. The employment of children is bad for children - first, as their health - and second, as to their manners. The time should be devoted to a better education. The employment of infant children on the cotton-mills furnishes a bad means to dissolute parents, to live in idleness and all sorts of vice." (35)

Blackfriars Rotunda

In May 1830 Carlile opened the Blackfriars Rotunda. Several times a week Carlile and invited speakers would "deliver attacks on the superstitions of Christianity, which Carlile had now identified as the single most obdurate opposition to reform and liberation". The Rotunda became an important centre for working-class dissent and political reform. Speakers included William Cobbett, Henry 'Orator' Hunt, Robert Owen, Daniel O'Connell, Robert Taylor and John Gale Jones. It is reported that at one meeting calling for parliamentary reform, drew a crowd of over 2,000 people. (36)

Richard Carlile was pleased with what he had achieved at the Rotunda: "We have created the best school that was ever open to the human race. Oxford, Cambridge, the London University, the King's College are Folly's seats, contrasted to the Rotunda. There has been more expansion of mind generated at the Rotunda, in the last year, than in all the world beside." (37)

Richard Carlile joined forces with William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, James Watson, John Cleave and William Benbow to form the National Union of the Working Classes (NUWC). It proposed universal male suffrage, annual parliaments, votes by secret ballot and the removal of property qualifications for MPs. Iain McCalman has claimed that it became the "most effective working-class radical organisation in the early 1830s." (38)

Carlile published an article in his new newspaper, The Prompter, in support of agricultural labourers campaigning against wage cuts. Carlile's advice to the labourers was "to go on as you have done". (39) This was interpreted by the authorities as a seditious call to arms. Carlile was arrested and charged with seditious libel and appeared at the Old Bailey in January 1831. Carlile argued that "neither in deed, nor in word, nor in idea, did I ever encourage acts of arson or machine breaking". (40)

The court was not convinced by his arguments and Carlile was found guilty of seditious libel and received a sentence of two years' imprisonment and a large fine which he refused to pay, thereby extending the sentence by a further six months. While in prison he continued to write articles for radical newspapers and pamphlets such as New View of Insanity (1831). (41)

Elizabeth Sharples

While he was in prison he received a letter from Elizabeth Sharples, a 28 year-old woman from Bolton. After "a rapid exchange of correspondence in which admiration turned to ardent love, she determined to share his work". (42) Even before he had met Sharples in person, Carlile anticipated that she would become "my daughter, my sister, my friend, my companion, my wife, my sweetheart, my everything". (43)

In January 1832 Elizabeth Sharples moved to London and visited Carlile in prison. Carlile had always campaigned for women's rights and he invited her to speak at his Blackfriars Rotunda. Billed as "the first Englishwoman to speak publicly on matters of politics and religion" she gave her first talk on 29th January 1832. (44) The Times reported that she was "pretty, with a good figure and genteel manners" and dressed very well. (45)

Sharples pointed out in her speech: "I will set before my sex the example of asserting an equality for them with their present lords and masters, and strive to teach all, yes, all, that the undue submission, which constitutes slavery, is honourable to none; while the mutual submission, which leads to mutual good, is to all alike dignified and honourable." (46) "Cast in the role of the Egyptian goddess Isis, she stood on the stage of the theatre, the floor strewn with whitethorn and laurel, and delivered lectures on mystical religion and women's rights." (47)

Elizabeth Sharples was appointed as editor of a new radical weekly publication, Isis. She gave two lectures every Sunday (at sixpence for the pit and boxes, one shilling for the gallery), on Monday evenings (for half-price). She also gave a free lecture on Friday evenings to accommodate those unable to afford the entry charges. (48)

Not everybody enjoyed her speeches. One man wrote to a national newspaper attacking the idea of a woman speaking in public: "Elizabeth Sharples is a female who exhibits herself in so unfeminine a manner... So utterly illiterate is the poor creature, that she cannot yet read what is set down for her with any degree of intelligibility... with her ignorance and unconquerable brogue... her lecturing is almost as ludicrous as it is painful to witness." (49)

Richard Carlile supported Sharples in her campaign for women's rights: "I do not like the doctrine of women keeping at home, and minding the house and the family. It is as much the proper business of the man as the woman; and the woman, who is so confined, is not the proper companion of the public useful man." (50) It has been claimed that "this just about sums up the position of women in the radical movement". Even if a woman was emancipated she was expected to be the "proper companion of the public useful man". (51)

Elizabeth Sharples argued in her newspaper articles that Christianity was the chief barrier to the dissemination of knowledge; by denying the people education, priests were denying man's liberty. She suggested that passive and non-resistance was seen as the "doctrine of priesthood". (52)

Sharples was Carlile's greatest supporter while he was in prison. She used the Rotunda platform" to castigate the priesthood, expose religious superstition and denigrate established authority". She promised "sweet revenge" on those responsible for the "incarceration of Carlile". She visited him in prison and began a sexual relationship. (53)

In 1832 Jane Carlile moved out of the family home and started a bookshop of her own. In April 1833 Elizabeth Sharples gave birth to a son, Richard Sharples. Carlile realized that he would have to acknowledge their relationship, and thereupon declared that he and Eliza were joined in a "moral marriage". (54)

Elizabeth Sharples had the task of running the Blackfriars Rotunda while Carlile was in prison. In February 1832, she reported that £1,000 was needed to keep the venture open, to cover rent, taxes, lights and repairs. At the same time there had been a reduction in audiences. She admitted that she had lost the support of the radical community: "I believe I stand alone in the country, as a modern Eve, daring to pluck the fruit of the tree, and to give it to timid, sheepish man. I have received kindnesses and encouragements from a few ladies since my appearance in the metropolis, but how few." (55)

Final Years

On his release from prison in August the couple lived on the corner of Bouverie Street and Fleet Street. Richard Sharples died of smallpox in October 1833. Another son, Julian Hibbert, was born in September 1834. In November 1835 they took a seven-year lease on a cottage in Enfield Highway, where shortly afterwards a daughter, Hypatia, was born. A fourth child, Theophila, followed a year later. (56)

In August 1836 he set off again on tour, lecturing first at Brighton and then to the north, returning home in December. His biographer, Philip W. Martin, pointed out: "Carlile's position was shifting radically. While it is clear that he never retreated to orthodoxy, his increasing use of Christian rhetoric and his own claims for himself as a Christian were a far cry from the radicalism of his early years. Carlile still propounded a sceptical, rational view of religion, but his allegorical readings had diminished to a single interpretation of Christianity in which he saw Christ and the resurrection as the rebirth of the soul of reason in humankind". (57)

Richard Carlile was still capable of drawing large crowds (1500 people in Leeds in 1839, and 3000 people in Stroud, in 1842), it was clear that most radicals rejected his religious views and were attracted to the political arguments of Chartism. He was also in poor health and he died of a bronchial infection on 10th February 1843. As he had dedicated his body to science it was taken to St Thomas's Hospital before his burial at Kensal Green Cemetery in London on 26th February.

Primary Sources

(1) Richard Carlile, who was one of the speakers at St. Peter's Field, wrote an account of what he witnessed in Sherwin's Weekly Political Register (18th August, 1819)

The meeting was one of the most calm and orderly that I have ever witnessed. No less than 300,000 people were assembled. Mr. Hunt started his speech when a cart was moved through the middle of the field to the great annoyance and danger of the assembled people, who quietly endeavoured to make way for its procedure. The cart had no sooner made its way through, when the Yeomanry Cavalry made their appearance from the same quarter as the cart had gone out. They galloped furiously round the field, going over every person who could not get out of their way.

The Yeomanry Cavalry made their charge with a most infuriate frenzy; they cut down men, women and children, indiscriminately, and appeared to have commenced a pre-meditated attack with the most insatiable thirst for blood and destruction. They merit a medallion, on one side of which should be inscribed 'The Slaughter Men of Manchester', and a reverse bearing a description of their slaughter of defenceless men, women and children, unprovoked and unnecessary. As a proof of meditated murder of the part of the magistrates, every stone was gathered from the ground on the Friday and Saturday previous to the meeting, by scavengers sent there by the express command of the magistrates, that the populace might be rendered more defenceless. The meeting was one of the most calm and orderly that I have ever witnessed. No less than 300,000 people were assembled. The Yeomanry Cavalry made their charge. They cut down men, women and children, and appeared to attack with a thirst for blood.

(2) Richard Carlile, The Republican (27th August, 1819)

The massacre of the unoffending inhabitants of Manchester, on the 16th of August, by the Yeomanry Cavalry and Police at the instigation of the Magistrates, should be the daily theme of the Press until the murderers are brought to justice.

Captain Nadin and his banditti of Police, are hourly engaged to plunder and ill-use the peaceable inhabitants; whilst every appeal from those repeated assaults to the Magistrates for redress, is treated by them with derision and insult.

Every man in Manchester who avows his opinions on the necessity of reform, should never go unarmed - retaliation has become a duty, and revenge an act of justice.

(3) In 1822 Susannah Wright was imprisoned for selling Richard Carlile's The Republican. During the trial she made the following comments.

As the blood of the Christian Martyrs become the seed of the Christian Church, so shall our sufferings become the seed of free discussion, and in those very sufferings we will triumph over you.

(4) Richard Carlile wrote an introduction to John Brown's Robert Blicoe's Memoir when it first appeared in The Lion newspaper on 25th January, 1828.

John Brown is now dead; he fell, about two or three years ago, by his own hand. He united, with a strong feeling for the injuries and sufferings of others. Hence his suicide. Had he not possessed a fine fellow-feeling with the child of misfortune, he would never have taken such pains to compile the Memoir of Robert Blincoe, and to collect all the wrongs on paper, on which he could gain information, about the various sufferers under the cotton-mill systems.

The employment of children is bad for children - first, as their health - and second, as to their manners. The time should be devoted to a better education. The employment of infant children on the cotton-mills furnishes a bad means to dissolute parents, to live in idleness and all sorts of vice.

(5) In 1835 Joseph Swann was sentenced to four and a half years for selling The Poor Man's Guardian. During the trial he explained his actions.

I have been unemployed for some time, neither can I obtain work, my family are starving. And for another reason, the most important of all, I sell them for the good of my countrymen.