On this day on 24th April

On this day in 1731 Daniel Defoe died. Defoe, the son of a butcher, was born in London in 1660. He attended Morton's Academy, a school for Dissenters at Newington Green with the intention of becoming a minister, but he changed his mind and became a hosiery merchant instead.

In 1685 Defoe took part in the Monmouth Rebellion and joined William III and his advancing army. Defoe became popular with the king after the publication of his poem, The True Born Englishman (1701). The poem attacked those who were prejudiced against having a king of foreign birth.

The publication of Defoe's The Shortest Way with the Dissenters (1702) upset a large number of powerful people. In the pamphlet, Defoe, a Dissenter, ironically demanded the savage suppression of dissent. The pamphlet was judged to be critical of the Anglican Church and Defoe was fined, put in the Charing Cross Pillory and then sent to Newgate Prison.

In 1703 Robert Harley, Earl of Oxford, a Tory government official, employed Defoe as a spy. With the support of the government, Defoe started the newspaper, The Review. Published between 1704 and 1713, the newspaper appeared three times a week. As well as carrying commercial advertising the newspaper reported on political and social issues. Defoe also wrote several pamphlets for Harley attacking the political opposition. The Whigs took Defoe court and this resulted in him serving another prison sentence.

In 1719 Defoe turned to writing fiction. His novels include: Robinson Crusoe (1719), Captain Singleton (1720), Journal of the Plague Year (1722), Captain Jack (1722), Moll Flanders (1722) and Roxanda (1724).

Defoe also wrote a three volume travel book, Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724-27) that provided a vivid first-hand account of the state of the country. Other non-fiction books include The Complete English Tradesman (1726) and London the Most Flourishing City in the Universe (1728). Defoe published over 560 books and pamphlets and is considered to be the founder of British journalism.

On this day in 1743 Edmund Cartwright, the son of a large landowner from Marnham, Nottingham. His brother, John Cartwright, was later to become one of the leaders of the parliamentary reform movement. After being educated at University College, Oxford, Cartwright became rector of the church at Goadby Marwood in Leicestershire.

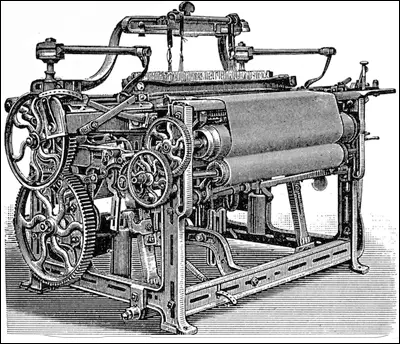

In 1784 Cartwright visited a factory owned by Richard Arkwright. Inspired by what he saw, he began working on a machine that would improve the speed and quality of weaving. Employing a blacksmith and a carpenter to help him, Cartwright managed to produce what he called a power loom. He took out a patent for his machine in 1785, but at this stage it performed poorly.

In 1787 Cartwright opened a weaving mill in Doncaster and two years later began using steam engines produced by James Watt and Matthew Boulton, to drive his looms. All operations that had been previously been done by the weaver's hands and feet, could now be performed mechanically. The main task of the weavers employed by Cartwright was repairing broken threads on the machine. Although these power looms were now performing well, Cartwright was a poor businessman and he eventually went bankrupt.

Cartwright now turned his attentions to over projects and took out a patent for a wool-combing machine (1790) and an alcohol engine (1797).

In 1799 a Manchester company purchased 400 of Cartwright's power looms but soon afterwards their factory was burnt to the ground, probably by workers who feared they would lose their jobs. This incident influenced other manufacturers from not buying Cartwright's machines.

By the early part of the 19th century a large number of factory owners were using a modified version of Cartwright's power loom. When Cartwright discovered what was happening he applied to the House of Commons for compensation. Some MPs such as Robert Peel, who had been one of those who had made a great deal of money from the modified power loom, supported his claim and in 1809 Parliament voted him a lump sum of £10,000.

Edmund Cartwright retired to a farm in Kent where he died on 30th October 1823.

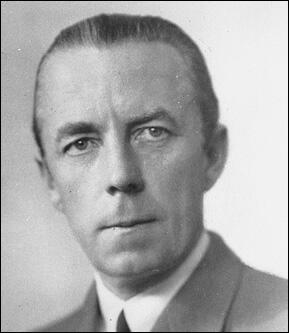

On this day in 1882 Air Marshal Hugh Dowding, the son of a schoolmaster, was born in Moffat, Scotland. He was educated at Winchester School and the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich. He joined the Royal Artillery Garrison he served as a subaltern at Gibraltar, Ceylon and Hong Kong before spending six years in India with mountain artillery troops.

On his return to Britain he learnt to fly. After obtaining his pilot's licence in December 1913, he joined the Royal Flying Corps. He was sent to France and in 1915 was promoted to commander of 16 Squadron.

After the Battle of the Somme, Dowding clashed with General Hugh Trenchard, the commander of the RFC, over the need to rest pilots exhausted by non-stop duty. As a result Dowding was sent back to Britain and although promoted to the rank of brigadier general, saw no more active service during the First World War.

Dowding now joined the recently created Royal Air Force and in 1929 was promoted to air vice marshal and the following year joined the Air Council.

In 1933 Dowding was promoted to air marshal and was knighted the following year. As a member of the Air Council for Supply and Research, he concentrated on research and development and helped prepare the RAF for war. This included a design competition that led to the production of the Hawker Hurricane and the Supermarine Spitfire. He was also responsible for encouraging the development of radar that became operational in 1937.

Dowding took command of Fighter Command where he argued that the Air Ministry should concentrate on development of aircraft for the defence of Britain rather than producing a fleet of bombers. Aware that the RAF would struggle against the Luftwaffe, Dowding advised Neville Chamberlain to appease Adolf Hitler in an attempt to gain time to prepare the country for war.

In 1940 Dowding worked closely with Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park, the commander of No. 11 Fighter Group, in covering the evacuation at Dunkirk. Although Dowding only had 200 planes at his disposal he managed to gain air superiority over the Luftwaffe. However, he was unwilling to sacrifice his pilots in what he considered to be a futile attempt to help Allied troops during the Western Offensive.

During the Battle of Britain Dowding was criticized by Air Vice-Marshal William Sholto Douglas, assistant chief of air staff, and Air Vice-Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, for not being aggressive enough. Douglas took the view that RAF fighters should be sent out to meet the German planes before they reached Britain. Dowding rejected this strategy as being too dangerous and argued it would increase the number of pilots being killed.

Dowding was credited with winning the Battle of Britain and was awarded the Knight Grand Cross. His old adversary, Hugh Trenchard, also told him that he had been guilty of gravely underestimating him for 26 years.

However, Air Chief-Marshal Charles Portal, the new chief of the air staff, had agreed with William Sholto Douglas in the dispute over tactics and in November 1941, and Dowding was encouraged to retire from his post. Douglas had the added satisfaction of taking over from Dowding as head of Fighter Command.

Dowding was now sent on special duty in the United States for the Ministry of Aircraft Production before retiring from the Royal Air Force in July, 1942. The following year he was honoured with a baronetcy.

In his retirement he published Many Mansions (1943), Lynchgate (1945), Twelve Legions of Angels (1946), God's Magic (1946) and The Dark Star (1951).

Hugh Dowding died on 15th February, 1970.

On this day in 1889 Jacob Golos was born into a Jewish family in Dnipropetrovsk, Russia, on 24th April, 1889. Kathryn S. Olmsted has argued: "He (Jacob Golos) had been born an outsider, a Jew in the anti-Semitic Russian empire. His family was rather wealthy, but, like many Jews in Russia, they were attracted by the Communist promise to overthrow the bloody Russian dictatorship. At the age of eight, he braved the secret police by distributing illegal Communist literature. When he was a teenager, the police threw him in prison for his Bolshevik activities."

As a young man he joined the Social Democratic Labour Party and in 1904 became active in the Bolsheviks. Golos took part in the 1905 Russian Revolution and helped to establish a Soviet in his local area. He also organized an illegal revolutionary printing. press.

In 1907 Golos was arrested "for operating a clandestine Bolshevik printing house". He was found guilty and sentenced to eight years hard labour. He was later exiled to Yakutia in Siberia. However, he managed to escape and was able to reach San Francisco in 1910. Soon afterwards he found employment as a printer. Over the next few years his sisters and parents also came to America.

Golos moved to New York City in 1912. He was active in both the Russian Socialist Federation and the Socialist Party of America. Golos also raised funds for the Bolshevik Party and after the Russian Revolution he returned to California and obtained employment as a fruit picker.

In September 1919, Jacob Golos joined Jay Lovestone, Earl Browder, John Reed, James Cannon, Bertram Wolfe, William Bross Lloyd, Benjamin Gitlow, Charles Ruthenberg, Mikhail Borodin, William Dunne, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Louis Fraina, Ella Reeve Bloor, Rose Pastor Stokes, Claude McKay, Max Shachtman, Martin Abern, Michael Gold and Robert Minor, in forming the Communist Party of the United States (CPUS). Within a few weeks it had 60,000 members whereas the Socialist Party of America had only 40,000.

In 1921 Golos began working as an organizer at the Communist Party in Chicago. Over the next few years he held a series of posts within the party. Kathryn S. Olmsted has pointed out: "The stocky, sandy-haired ideologue was deeply involved in Party factional disputes and organizational efforts. By the early 1920s he was helping to organize workers and to write, edit, publish, and distribute Communist newspapers. The fledgling Bureau of Investigation began to follow his activities as early as 1922."

In 1926 he returned to the Soviet Union. Two years later, Jay Lovestone, the General Secretary of the CPUS, requested the return of Jacob Golos: "Comrade Golos has considerable influence among Russian laboring masses in the United States." Golos also became involved in intelligence work and by 1933 he was working for Gaik Ovakimyan, the NKVD station chief in New York City. Secret Soviet intelligence cables from Golos as "our reliable man in the U.S."

According to Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999): "Through bribes, Golos developed a network of foreign consular officials and U.S. passport agency workers who supplied him not only with passports but also naturalization documents and birth certificates belonging to persons who had died or had permanently left the United States."

In 1934 Golos became the head of its Central Control Commission. It was his job to make sure that all members of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUS) followed party policy that was being directed by Joseph Stalin. The historian, Anthony Cave Brown, compared the commission in his book, On a Field of Red: The Communist Internationaland the Coming of World War One (1981) to the Spanish Inquisition: "As with Tomas de Torquemada and Isabella I of Spain, so with Golos and Stalin."

Jacob Golos met Elizabeth Bentley for the first time on 15th October, 1938. Kathryn S. Olmsted described their first meeting in her book, Red Spy Queen (2002) with the spy who told her his name was Timmy: "Like any good spy, Golos did not stand out in a crowd. A heavy-set, rather nondescript man in a bad suit and scuffed shoes, he did not make a favorable first impression on Elizabeth. At five feet two inches, he was seven inches shorter than the strapping young woman he hoped to use as a source. She eyed with disapproval his tattered felt hat and shabby car." However, she gradually changed her mind about Golos: "He seemed intelligent and thoughtful. Soon she found herself telling him the story of her life, including her disappointing earlier contacts with the Soviet underground. As she warmed to him, Timmy seemed to grow better looking. He was no longer short and squat but 'powerfully built'; he was not colorless but had 'startlingly blue' eyes that stared straight into hers... Though she was intimidated, she felt flattered by the attention that this powerful Communist was giving her."

Elizabeth Bentley agreed to become a Soviet spy. He told her. "You are no longer an ordinary Communist but a member of the underground. You must cut yourself off completely from all your old Communist friends." Instead she was to mix with fascists in New York City. Her friends might regard her as a traitor, but "the Party would not ask this sacrifice of you if it were not vitally important."

In September 1939, Major Pavel Fitin, now the head of NKVD's foreign intelligence unit, reported to Lavrenty Beria, the Commissioner of Internal Affairs, that: "The American Trotskyite organization is the strongest in membership and financing among all the Trotskyite groupings." A memorandum was circulated that suggested that one of the most important Soviet spies in America, Jacob Golos, was not to be trusted: "since he knows a great deal about the station's work, I would consider it expedient to bring him to the Soviet Union and arrest him." Later that month Fitin wrote to Beria proposing the recall of two agents that had been "exposed to the agent Golos, who is strongly suspected of Trotskyite activities". However, Golos was an American citizen and refused offers to visit Moscow.

Jacob Golos ran a travel agency, World Tourists in New York City. It was a front for Soviet clandestine work. Soon after he recruited Bentley as a spy, his office was raided by officials of the Justice Department. Some of these documents showed that Earl Browder, the leader of the Communist Party of the United States, had travelled on a false passport. Browder was arrested and Golos told Bentley: "Earl is my friend. It is my carelessness that is going to send him to jail." Bentley later recalled that the incident took its toll on Golos: "His red hair was becoming grayer and sparser, his blue eyes seemed to have no more fire in them, his face became habitually white and taut."

According to Bentley, United States officials agreed to drop the whole investigation, if Golos pleaded guilty. He told her that Moscow insisted that he went along with the deal. "I never thought that I would live to see the day when I would have to plead guilty in a bourgeois court." He complained that they had forced him to become a "sacrificial goat". On 15th March, 1940, Golos received a $500 fine and placed on four months probation.

The FBI continued to follow Golos and on 18th January, 1941, they saw him exchange documents with Gaik Ovakimyan. The FBI also observed Golos meeting Elizabeth Bentley at the offices of the of the U.S. Service and Shipping Corporation. The agents wondered if she might be a Soviet spy as well and she was followed. On 23rd May, 1941, Ovakimyan was arrested and deported. Bentley was followed until surveillance was stopped on 20th August, 1941.

Moscow instructed Golos to be far more careful with his contacts with his network. John Hazard Reynolds was selected to take over the running of the U.S. Service and Shipping Corporation. Reynolds was a millionaire who put up $5,000 in capital. The Communist Party of the United States also donated $15,000 to help run the company. Reynolds employed Bentley as vice president of the company as a cover for her spying operations. However, she did not get on well with Reynolds: "His slightly arrogant manner and his accent said loudly Park Avenue, the Racket Club, and the Plaza."

Golos health began to deteriorate and so Elizabeth Bentley began to take over some of his duties. This included visiting Washington to pick up documents from Nathan Silvermaster who lived in a flat with his wife and another spy, Ludwig Ullman. Helen Silvermaster was highly suspicious of Bentley and she told Golos that she was convinced that she was an undercover agent for the FBI. Golos told her that she was being ridiculous and that she had no choice but to work with her. The Silvermasters reluctantly accepted Bentley as their new contact."

Silvermaster and Ullman became an important source of material: As Kathryn S. Olmsted, the author of Red Spy Queen (2002), points out: "Every two weeks, Elizabeth would travel to Washington to pick up documents from the Silvermasters, collect their Party dues, and deliver Communist literature. Soon the flow of documents grew so large that Ullmann, an amateur photographer, set up a darkroom in their basement. Elizabeth usually collected at least two or three rolls of microfilmed secret documents, and one time received as many as forty. She would stuff all the film and documents into a knitting bag or other innocent feminine accessory, then take it back to New York on the train. The knitting bag soon bulged with critical documents from the U.S. government."

Another important spy was William Remington. An economist, he also worked for the National Resources Planning Board and the Office of Price Administration of the Office for Emergency Management. In February 1942 he joined the War Production Board. It has been claimed that: "Remington and his wife, Ann, longed to reestablish contact with the Party in Washington, but they knew that open membership would hurt Bill's career. As a solution some Party friends introduced them to a mysterious, redheaded man with an Eastern European accent." The man's real name was Jacob Golos and he passed him onto Bentley.

Over the next two years, Bentley met Remington on a regular basis. She later recalled that he gave her classified information on aircraft production and testing. She claimed that "he was one of the most frightened people with whom I have ever had to deal". Eventually, he refused to meet Bentley and openly joined pro-Communist organizations in the hope that he would lessen his value as a spy. Bentley dismissed Remington as "a small boy trying to avoid moving the lawn or cleaning out the furnace when he would much rather go fishing." Bentley advised Golos that they should drop him but he insisted that they remained in contact as other powerful members of the network might be able to "push him into a really good position."

Elizabeth Bentley knew that Jacob Golos was a dying man: "I knew now that Yasha was a dying man and that the end might come at any moment - it was only by some miracle of will power he was still alive." Golos also began to question the policies of Joseph Stalin. Bentley later said that "he said he fought for Communism and now he was beginning to wonder."

Bentley woke up on 27th November, 1943, hearing "horrible choking sounds" coming from her lover. She tried frantically to wake him from what appeared to be a heart attack. Bentley called an ambulance but the doctors were unable to revive him. When the police arrived she pretended that she worked with the man and had just called in to see how he was because she knew he had been ill. Bentley then travelled to his office and destroyed all the documents in the safe.

On this day in 1889 Richard Stafford Cripps was born in London. His mother, Theresa Cripps, was the sister of Beatrice Webb. After an education at Winchester and New College, one of the 39 constituent colleges of Oxford University, he became a research chemist. He also carried on studying law and was called to the bar in 1913.

Cripps was a pacifist and during the First World War served with the Red Cross in France. In 1918 Cripps returned to his work as a barrister. Specializing in company law, Cripps made a fortune in patent and compensation cases.

A Christian Socialist and member of the Labour Party, Cripps was elected to the House of Commons in 1931 at a by-election in East Bristol. The following year Ramsay MacDonald appointed Cripps as his solicitor-general. However, like most members of the party, Cripps refused to serve in MacDonald's National Government formed in 1931.

Stafford Cripps was converted to Marxism and became the leader of the left-wing of the Labour Party. Other members of this group included Aneurin Bevan, William Mellor, Ellen Wilkinson, Barbara Betts, Frank Wise, Jennie Lee, Harold Laski, Frank Horrabin, Barbara Betts and G. D. H. Cole. In 1932 the group established the Socialist League. Other members included Charles Trevelyan, Stafford Cripps, D. N. Pritt, R. H. Tawney, David Kirkwood, Clement Attlee, Neil Maclean, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Alfred Salter, Jennie Lee, Gilbert Mitchison, Ellen Wilkinson, Ernest Bevin, Arthur Pugh and Michael Foot. Margaret Cole admitted that they got some of the members from the Guild Socialism movement: "Douglas and I recruited personally its first list drawing upon comrades from all stages of our political lives." The first pamphlet published by the SSIP was The Crisis (1931) was written by Cole and Bevin.

According to Ben Pimlott, the author of Labour and the Left (1977): "The Socialist League... set up branches, undertook to promote and carry out research, propaganda and discussion, issue pamphlets, reports and books, and organise conferences, meetings, lectures and schools. To this extent it was strongly in the Fabian tradition, and it worked in close conjunction with Cole's other group, the New Fabian Research Bureau." The main objective was to persuade a future Labour government to implement socialist policies.

G.D.H. Cole arranged for Ernest Bevin to be elected chairman of the Socialist League. However, the following year, the Independent Labour Party members insisted on Frank Wise becoming chairman. Cole wrote later, "as the outstanding Trade Union figure capable of rallying Trade Union opinion behind it I voted against... but I was outvoted and agreed to go with the majority". Cole attempted to persuade Bevin to join the Socialist League Executive, but he refused: "I do not believe the Socialist League will change very much from the old ILP attitude, whoever is in the Executive."

In April 1933 G.D.H. Cole, R. H. Tawney and Frank Wise, signed a letter urging the Labour Party to form a United Front against fascism, with political groups such as the Communist Party of Great Britain. However, the idea was rejected at that year's party conference.

With the rise of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany, Stafford Cripps became convinced that the Labour Party should establish a United Front against fascism with the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Independent Labour Party. In April 1934 William Mellor had a meeting with Fenner Brockway and Jimmy Maxton, two leaders of the ILP, "to talk over ways and means of securing working-class unity". He also had meetings with Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

In 1936 the Conservative government in Britain feared the spread of communism from the Soviet Union to the rest of Europe. Stanley Baldwin, the British prime minister, shared this concern and was fairly sympathetic to the military uprising in Spain against the left-wing Popular Front government. Leon Blum, the prime minister of the Popular Front government in France, initially agreed to send aircraft and artillery to help the Republican Army in Spain. However, after coming under pressure from Baldwin and Anthony Eden in Britain, and more right-wing members of his own cabinet, he changed his mind.

In the House of Commons on 29th October 1936, Clement Attlee, Philip Noel-Baker and Arthur Greenwood argued against the government policy of Non-Intervention. As Noel-Baker pointed out: "We protest with all our power against the sham, the hypocritical sham, that it now appears to be." Cole and Jack Murphy, the General Secretary of the Socialist League also called for help to be given to the Popular Front government.

Stafford Cripps was another advocate for an United Front: "Up till recent times it was the avowed object of the Communist Party to discredit and destroy the social democratic parties such as the British Labour Party, and so long as that policy remained in force, it was impossible to contemplate any real unity... The Communists had... disavowed any intention, for the present, of acting in opposition to the Labour Movement in the country, and certainly their action in many constituences during the last election gives earnest of their disavowal." Aneurin Bevan added: "It is of paramount importance that our immediate efforts and energies should be directed to organising a United Front and a definite programme of action."

In 1936 the Socialist League joined forces with the Communist Party of Great Britain, the Independent Labour Party and various trades councils and trade union brances to organize a large-scale Hunger March. Aneurin Bevan argued: "Why should a first-class piece of work like the Hunger March have been left to the initiative of unofficial members of the Party, and to the Communists and the ILP... Consider what a mighty response the workers would have made if the whole machinery of the Labour Movement had been mobilised for the Hunger March and its attendant activities."

On 31st October, 1936 the Socialist League called an anti-fascist conference in Whitechapel and discussed the best ways of dealing with Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists. Over the next few months meetings were held. The Socialist League was represented by Stafford Cripps and William Mellor, the Communist Party of Great Britain by Harry Pollitt and Palme Dutt and the Independent Labour Party by James Maxton and Fenner Brockway.

Stafford Cripps was the main supporter of a United Front in the Socialist League: "The Communist Party and the ILP may not represent very large numbers, but all of us who have knowledge of militant working-class activities throughout the country are bound to admit that Communists and ILPers have played and are playing a very fine part in such activities... Just as unity has wrought wonders in Spain, inspiring and encouraging the Spanish workers with a heroism past all praise, so in our, as yet, less arduous struggle it can give new life and vitality."

Richard Crossman disagreed with Cripps and his followers: "The Socialist League... dilate on the need for Communist affiliation and a strong policy with regard to Spain, as though these items were of the slightest interest to any save the minority of politically conscious electors. Such critics frame their propaganda to satisfy their own tastes and neglect the simple fact that it is not they but the Tory voters who must be converted. Their busy activity is self-intoxicating, but millions of people still read the racing page, because, on the whole, conditions are not bad enough to drive them to politics, and they have not seen a Labour canvasser for five years, far less seen any signs of practical activity by the local Labour Party."

After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Cripps campaigned for the formation of a Popular Front with other left-wing groups in Europe to prevent the spread of fascism. In January 1937 Stafford Cripps and George Strauss decided to launch a radical weekly, The Tribune, to "advocate a vigorous socialism and demand active resistance to Fascism at home and abroad." William Mellor was appointed editor and others such as Barbara Betts, Aneurin Bevan, Ellen Wilkinson, Barbara Castle, Harold Laski, Michael Foot and Noel Brailsford agreed to write for the paper.

William Mellor wrote in the first issue: "It is capitalism that has caused the world depression. It is capitalism that has created the vast army of the unemployed. It is capitalism that has created the distressed areas... It is capitalism that divides our people into the two nations of rich and poor. Either we must defeat capitalism or we shall be destroyed by it." Stafford Cripps wrote encouragingly after the first issue: "I have read the Tribune, every line of it (including the advertisements!) as objectively as I can and I must congratulate you upon a very first-rate production.''

Richard Stafford Cripps declared that the mission of the Socialist League and The Tribune was to recreate the Labour Party as a truly socialist organization. This soon brought them into conflict with Clement Attlee and the leadership of the party. Hugh Dalton declared that "Cripps Chronicle" was "a rich man's toy".

The United Front agreement won only narrow majority at a Socialist League delegate conference in January, 1937 - 56 in favour, 38 against, with 23 abstentions. The United Front campaign opened officially with a large meeting at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester on 24th January. Three days later the Executive of the Labour Party decided to disaffiliated the Socialist League. They also began considering expelling members of the League. Cole and George Lansbury responded by urging the party not to start a "heresy hunt".

Arthur Greenwood was one of those who argued that Stafford Cripps should be immediately expelled. Ernest Bevin agreed: "I saw Mosley come into the Labour Movement and I see no difference in the tactics of Mosley and Cripps." On 24th March, 1937, the National Executive Committee declared that members of the Socialist League would be ineligible for Labour Party membership from 1st June. Over the next few weeks membership fell from 3,000 to 1,600. In May, G.D.H. Cole and other leading members decided to dissolve the Socialist League.

By 1938 Stafford Cripps and George Strauss had lost £20,000 in publishing The Tribune. The successful publisher, Victor Gollancz, agreed to help support the newspaper as long as it dropped the United Front campaign. When William Mellor refused to change the editorial line, Cripps sacked him and invited Michael Foot to take his place. However, as Mervyn Jones has pointed out: "It was a tempting opportunity for a 25-year-old, but Foot declined to succeed an editor who had been treated unfairly."

Cripps and Aneurin Bevan were also involved in the campaign against appeasement. This included speaking on the same platform with members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. In his autobiography, Very Little Luggage, his friend, Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, explained what happened: "The result was that Cripps, Bevan and myself (midget though I was beside such men) received a letter of anathema from the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party. We were told that we would be expelled from the Labour Party if we continued to appear on platforms that included Communists.... So I found myself sitting in an office in Chancery Lane with Cripps and Bevan while Cripps held up the letter to re-read the National Executive's terms for our rehabilitation. Cripps treated it as though it were a document replete with indecent details in a carnal knowledge case. Bevan said something about preferring to be out than in. The way things were going, so he said, it was no time to be mealy-mouthed. So they refused to assure the National Executive that they would in future keep more right-wing company."

Richard Stafford Cripps, Aneurin Bevan, George Strauss and Charles Trevelyan were readmitted in November 1939 after agreeing "to refrain from conducting or taking part in campaigns in opposition to the declared policy of the Party."

For the first two years of the Second World War Cripps and Bevan provided the main opposition to Britain's coalition government. In a survey carried out in 1941, the public was asked who should be prime minister if anything should happen to Winston Churchill. Of those who replied, 37% said Anthony Eden and a surprising 34% selected Cripps.

Churchill now became concerned about having one of his main critics so high in the polls. In 1942 Churchill appointed Cripps as Lord Privy Seal in his government and put him in the War Cabinet. However, Cripps continued to question Churchill's war strategy and in October 1942 he was removed from the War Cabinet. He remained in the government and now became Minister of Aircraft Production.

On Cripps removal from the War Cabinet, Hugh Dalton recorded in his diary: "He has, I think, been very skilfully played by the P.M. He may, of course, be quite good at the Ministry of Aircraft Production, but seldom has anyone's political stock, having been so outrageously and unjustifiably overvalued, fallen so fast and so far."

In 1945 Cripps published his book Towards a Christian Democracy and his readmittance to the Labour Party. Following the 1945 General Election, the new Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, appointed Cripps as Minister of Trade. Two years later Cripps replaced Hugh Dalton as Chancellor of the Exchequer. His policy of high taxation, tight public spending and a voluntary wage freeze, helped to keep inflation in Britain under control.

In October 1950 poor health forced him to resign from the government. The following year was elected as President of the Fabian Society.

Richard Stafford Cripps died ion 21st April 1952.

On this day in 1906 William Joyce, the first of three sons of Michael Francis Joyce and his wife, Gertrude Emily Brooke, was born in New York City. His mother was English and his father was a naturalized Irishman who worked as a builder and contractor. According to his biographer, Siân Nicholas: "The family returned to Ireland in 1909, where Joyce was educated in Roman Catholic schools, including the Jesuit St Ignatius Loyola College. The Joyces were, however, ardent loyalists, and Joyce later claimed to have fought as a boy alongside the Black and Tans."

In 1922 he emigrated to England with his family. He attended the University of London where he graduated with a first class honours degree. While he was at university William Joyce became heavily involved in extreme right-wing politics. In 1923 Joyce joined the British Fascisti (BF). Its leader, Miss Rotha Lintorn-Orman later said: "I saw the need for an organization of disinterested patriots, composed of all classes and all Christian creeds, who would be ready to serve their country in any emergency." Members of the British Fascists had been horrified by the Russian Revolution. However, they had gained inspiration from what Benito Mussolini had done it Italy.

The BF were unpopular in some areas and during the 1924 General Election, on 22nd October, William Joyce took part in a scuffle with members of the Communist Party of Great Britain in Lambeth and received a razor cut from the corner of his mouth to behind his right ear.

In 1925 Maxwell Knight, the Director of Intelligence of the British Fascisti, was recruited by MI5. He was placed in charge of B5b, a unit that conducted the monitoring of political subversion. Knight recruited a large number of his agents from right-wing political organizations. It was later discovered that Joyce was one of MI5's agents. Over the next few years Joyce provided Knight with information he had about the activities of the Communist Party and other left-wing groups.

Like other members of the British Fascisti, Joyce had a deep hatred of Jews and Communists. He claimed that his facial wound had been caused by a "Jewish Communist". He also blamed his failure to complete his MA on a Jewish woman tutor. On 30th April 1927 he married Hazel Katherine Barr at Chelsea register office. The couple had two daughters. This seemed to settle Joyce down and in 1928 he joined the Conservative Party.

In early 1933 William Joyce joined the British Union of Fascists (BUF) led by Oswald Mosley. The BUF was strongly anti-communist and argued for a programme of economic revival based on government spending and protectionism. Mary Richardson later commented: "I was first attracted to the Blackshirts because I saw in them the courage, the action, the loyalty, the gift of service, and the ability to serve which I had known in the suffrage movement". Mosley appointed Joyce as the party full-time Propaganda Director and deputy leader of BUF.

Charles Bentinck Budd was elected to the Worthing Town Council as a member of the BUF in October 1933. The national press reported that Worthing was the first town in the country to elect a Fascist councillor. Worthing was now described as the "Munich of the South". Oswald Mosley announced that Budd was the BUF Administration Officer for Sussex . On Friday 1st December 1933, the BUF held its first public meeting in Worthing in the Old Town Hall. According to the author of Storm Tide: Worthing 1933-1939 (2008): "It was crowded to capacity, with the several rows of seats normally reserved for municipal dignitaries and magistrates now occupied by forbidding, youthful men arrived in black Fascist uniforms, in company with several equally young women dressed in black blouses and grey skirts."

On 4th January, 1934, Budd reported that over 150 people in Worthing had joined the British Union of Fascists. He claimed that the greatest intake had come from increasingly disaffected Conservatives. The Weekly Fascist News described the growth in membership as "phenomenal". Budd also announced that local communists had broken into his offices at 27 Marine Parade and stolen 96 BUF badges, together with cigarettes and £2.2s.8d in cash. However, soon afterwards the police arrested Cyril Mitchell of 16 Leigh Road, Broadwater. Mitchell, who admitted the offence, was in fact a young Blackshirt, who had broken into the offices after a night out in the pub. He told the police, "something came over me… I had too much beer".

The mayor of Worthing, Harry Duffield, the leader of the Conservative Party in the town, was most favourably impressed with the Blackshirts and congratulated them on the disciplined way they had marched through the streets of Worthing. He reported that employers in the town had written to him giving their support for the British Union of Fascists. They had "no objection to their employees wearing the black shirt even at work; and such public spirited action on their part was much appreciated."

On 26th January, 1934, William Joyce addressed a public meeting at the Pier Pavilion. Over 900 people turned up to hear Joyce speak. In his speech he pledged to free British industry from foreigners, "be they Hebrew or any other form of alien." Joyce ended his two-hour speech with: "Reclaim what is your own in the fullness of Fascist victory!"

The London Evening News, another newspaper owned by Lord Rothermere, found a more popular and subtle way of supporting the Blackshirts. It obtained 500 seats for a BUF rally at the Royal Albert Hall and offered them as prizes to readers who sent in the most convincing reasons why they liked the Blackshirts. Another title owned by Rothermere, The Sunday Dispatch, even sponsored a Blackshirt beauty competition to find the most attractive BUF supporter. Not enough attractive women entered and the contest was declared void.

By 1934 the British Union of Fascists had 40,000 members and was able to establish its own drinking clubs and football teams. The BUF also gained the support of Lord Rothermere and the Daily Mail. On 7th June, 1934, the BUF held a large rally at Olympia. About 500 anti-fascists including Vera Brittain, Richard Sheppard and Aldous Huxley, managed to get inside the hall. When they began heckling Oswald Mosley they were attacked by 1,000 black-shirted stewards. Several of the protesters were badly beaten by the fascists.

Margaret Storm Jameson pointed out in The Daily Telegraph: "A young woman carried past me by five Blackshirts, her clothes half torn off and her mouth and nose closed by the large hand of one; her head was forced back by the pressure and she must have been in considerable pain. I mention her especially since I have seen a reference to the delicacy with which women interrupters were left to women Blackshirts. This is merely untrue... Why train decent young men to indulge in such peculiarly nasty brutality?"

The Daily Mail continued to give its support to the fascists. George Ward Price wrote about anti-fascist demonstrators at a meeting of the National Union of Fascists on 8th June, 1934: "If the Blackshirts movement had any need of justification, the Red Hooligans who savagely and systematically tried to wreck Sir Oswald Mosley's huge and magnificently successful meeting at Olympia last night would have supplied it. They got what they deserved. Olympia has been the scene of many assemblies and many great fights, but never had it offered the spectacle of so many fights mixed up with a meeting."

Collin Brooks, was a journalist who worked for Lord Rothermere at the The Sunday Dispatch. He also attended the the rally at Olympia. Brooks wrote in his diary: "He mounted to the high platform and gave the salute - a figure so high and so remote in that huge place that he looked like a doll from Marks and Spencer's penny bazaar. He then began - and alas the speakers hadn't properly tuned in and every word was mangled. Not that it mattered - for then began the Roman circus. The first interrupter raised his voice to shout some interjection.The mob of storm troopers hurled itself at him. He was battered and biffed and hashed and dragged out - while the tentative sympathisers all about him, many of whom were rolled down and trodden on, grew sick and began to think of escape. From that moment it was a shambles. Free fights all over the show. The Fascist technique is really the most brutal thing I have ever seen, which is saving something. There is no pause to hear what the interrupter is saying: there is no tap on the shoulder and a request to leave quietly: there is only the mass assault. Once a man's arms are pinioned his face is common property to all adjacent punchers." Brooks also commented that one of his "party had gone there very sympathetic to the fascists and very anti-Red". As they left the meeting he said "My God, if ifs to be a choice between the Reds and these toughs, I'm all for the Reds".

MI5 also reported to the Home Office that the rally would have a negative impact on the future of the National Union of Fascists: "It is becoming increasingly clear that at Olympia Mosley suffered a check which is likely to prove decisive. He suffered it, not at the hands of the Communists who staged the provocations and now claim the victory; but at the hands of Conservative MPs, the Conservative press and all those organs of public opinion which made him abandon the policy of using his Defence Force to overwhelm interrupters."

It was announced that Charles Bentinck Budd had arranged for Sir Oswald Mosley and William Joyce to address a meeting at the Pavilion on 9th October, 1934. The venue was packed with fascist supporters. The meeting was disrupted when a few hecklers were ejected by hefty East End bouncers. Mosley, however, continued his speech undaunted, telling his audience that Britain's enemies would have to be deported: "We were assaulted by the vilest mob you ever saw in the streets of London - little East End Jews, straight from Poland. Are you really going to blame us for throwing them out?"

At the close of the proceedings the main body of uniformed Fascists, led by Joyce, emerged from the Pavilion on to the Esplanade. It was estimated that there were 2,000 people waiting outside. The crowd surged forward and several fights began. A ninety-six-year-old woman, Doreen Hodgkins, was struck on the head by a Blackshirt before being escorted away. When the Blackshirts retreated inside, the crowd began to chant: "Poor old Mosley's got the wind up!"

The author of Storm Tide: Worthing 1933-1939 (2008) has pointed out: "By this time all nineteen available members of the Borough's police force had been called out, and through their combined efforts a lane through the crowd was forced open from the Pavilion steps across the Esplanade to Marine Parade. But as Joyce and his re-formed black-shirted cohort passed along it they were constantly barracked and jostled; while the sudden appearance of Sir Oswald himself, together with the bodyguards of his Defence Force, led to a further outbreak of scuffles on the Esplanade as large numbers of spectators eagerly closed in upon him. One Blackshirt was knocked to the ground and there were shouts for Sir Oswald to be thrown into the sea... Despite such imprecations, however, the mood of the majority remained largely good-natured: most people, prompted by curiosity and awe, simply wanting to get a closer, more proper, look at such a famous yet notorious figure. But Sir Oswald, clearly out of countenance and feeling menaced, at once ordered his tough, battle-hardened bodyguards - all of imposing physique and, like their leader, towering over the policemen on duty - to close ranks and adopt their fighting stance which, unsurprisingly, as all were trained boxers, had been modelled on, and closely resembled, that of a prize fighter."

Chris Hare, the author of Historic Worthing (2008) has argued: "Mosley, accompanied by William Joyce, left the Pavilion and, protected by a large body of blackshirts, crossed over the road to Barnes's cafe in the Arcade. Stones and rotten vegetables were soon crashing through the windows of the cafe. Boys were observed firing peashooters at the beleaguered Fascists, while some youths were taking aim with air rifles. Meanwhile a group of young men climbed onto the roof of the Arcade and dislodged a large piece of masonry, which plummeted to earth through the arcade, landing only feet away from the Fascist leader. Things were getting too hot for the Fascists, who made a run for it, up the Arcade into Montague Street, then into South Street. Their intention was presumably to reach either their headquarters in Ann Street, or The Fountain in South Street, known as a 'Fascist pub', but they were ambushed on the corner of Warwick Street by local youths. Hearing the row, more Fascists hurried down from the Fountain to go to Mosley's aid. Fights broke out, bodies were slung against shop windows, and startled residents threw open their windows to see a seething mass of entangled bodies desperately struggling for control of the junction between South Street and Warwick Street."

Superintendent Bristow later claimed that a crowd of about 400 people attempted to stop the Blackshirts from getting to their headquarters. A series of fights took place and several people were injured. Francis Skilton, a solicitor's clerk who had left his home at 30 Normandy Road to post a letter at the Central Post Office in Chapel Road, and got caught up in the fighting. A witness, John Birts, later told the police that Skilton had been "savagely attacked by at least three Blackshirts." It was not until 11.00 p.m. that the police managed to clear the area.

Under the influence of Joyce the BUP became increasingly anti-Semitic. The verbal attacks on the Jewish community led to violence at meetings and demonstrations. In November 1936 a serious riot took place when left-wing organisations successfully stopped Mosley marching through the Jewish areas of London.

The activities of the BUF was checked by the the passing of the 1936 Public Order Act. This gave the Home Secretary the power to ban marches in the London area and police chief constables could apply to him for bans elsewhere. This legislation also made it an offence to wear political uniforms and to use threatening and abusive words.

The BUP anti-Semitic policy was popular in certain inner-city areas and in 1937 Joyce came close to defeating the Labour Party candidate in the London County Council election in Shoreditch. Joyce argued that the BUP should take a more extreme position on racial issues. Mosley disagreed and began to feel that Joyce posed a threat to his leadership. He therefore decided to sack Joyce as Propaganda Director. In an attempt to save money another 142 staff members also lost their jobs.

William Joyce now decided to leave the organization and with the help of John Becket and A. K. Chesterton he founded the National Socialist League. In a pamplet, National Socialism Now, Joyce began to express views similar to those of Adolf Hitler. He wrote: "International Finance is controlled by great Jewish moneylenders and Communism is being propagated by Jewish agitators who are at one fundamentally with the powerful capitalists of their race in desiring an international world order, which would, of course, give universal sovereignty to the only international race in existence."

When Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of Czechoslovakia Joyce became convinced that war with Germany was inevitable. Unwilling to fight against Hitler's forces, Joyce began to consider leaving the country. This view was reinforced when he was warned by Maxwell Knight of MI5 that the British government was considering the possibility of interning fascist leaders.

On 26th August, 1939, Joyce left for Nazi Germany. Soon after arriving in Berlin he found work with the German Radio Corporation as an English language broadcaster. Joyce joined the 'German Calling' programme. On 14th September, 1939, a report in the Daily Express described the broadcaster as speaking the "English of the haw-haw, damit-get-out-of-my-way variety." It was not long before Joyce became known as Lord Haw-Haw.

Joyce continued to broadcast throughout the Second World War. In 1940 the Daily Mirror organized the Anti Haw Haw League of Loyal Britons and members pledged not to listen to these broadcasts. Other British subjects who took part in these broadcasts included John Amery, Railton Freeman, Norman Baillie-Stewart, Kenneth Lander and William Griffiths.

On 17th June, 1940, William Joyce broadcasted a message to the British public on Winston Churchill: "Mr Churchill said tonight that Britain now stands alone. Did he tell you that on 3rd September, 1939? On the contrary, then he said that Germany stood alone, to be throttled by the British blockade without even the sacrifice of a single British soldier. How many of the BEF, how many of the British Navy and the RAF have already been sacrificed only that your Prime Minister could tell you that you now stand alone? Was it worth it? Surely not. Surely the time has come to meet the bill, the bill that Mr Churchill and his accomplices ran up for you, and which you will be called upon to meet if you do not force your Government to meet it."

The BBC was asked to provide a report on William Joyce's broadcasts: "That picture is of an England where the people are misled by corrupt and irresponsible leaders, where the small wealthy class leaves the masses to misery, unemployment, hunger and exploitation; of an Empire built on brutality and rapacity, now as decadent and as divided as its Mother Country; of an England hated by the world for her selfishness and ruthlessness. The picture in outline resembles the Roman Empire in the Fourth Century AD - itself decrepit and superannuated, but striving to hold its place in the world by playing off one neighbour against another. From such a portrait it follows that in the present war, Germany - a fresh new power - is fighting to free herself and the world from the tyrannous shackles of Britain; or, with greater accuracy, to free herself, the world, and the British masses, from the tyrannous fetters of the British ruling class. Rarely, if ever, do the Hamburg broadcasts make their picture so clear-cut as it has been made here, but every separate news item is selected or twisted, every talk is designed, to take its place as a facet in such a general picture. As in half-tone block the picture is composed dot by dot. If this picture is accepted by the British people, the German aim is achieved."

Joyce was captured by the British Army at Flensburg on 28th May 1945. Three days later Joyce was interrogated by William Scardon, an MI5 officer. Joyce made a full confession but at first the Director of Prosecutions doubted whether he could be tried for treason as he had been born in the United States. However, his broadcasts during the war had made him a hate figure in Britain and the Attorney General, David Maxwell-Fyfe, decided to charge him with high treason.

Joyce's trial for high treason began at the Old Bailey on 17th September, 1945. In court it was stated that although he was United States citizen he had held a British passport during the early stages of the war. It was therefore argued in court by Hartley Shawcross that Joyce had committed treason by broadcasting for Germany between September 1939 and July 1940, when he officially became a German citizen.

William Joyce was found guilty of treason and was executed on 3rd January 1946.

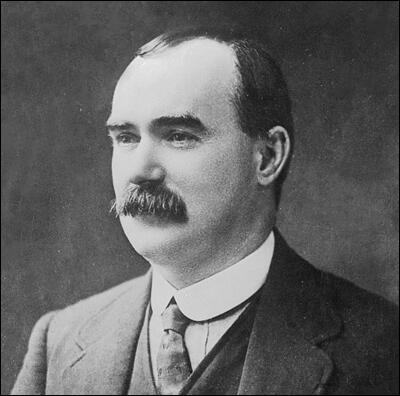

On this day in 1916 James Connolly takes part in the Easter Rising. Connolly was born in Edinburgh in 1868. He joined the British Army and served in Ireland. However, he deserted in 1889 and returned to Scotland where he did a variety of different jobs.

Connolly became a socialist and in 1896 moved to Dublin as an organizer of the Dublin Socialist Society. Later he founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party and established The Workers' Republic in 1898. Books by Connolly during this period included Erin's Hope (1897) and The New Evangel (1901).

In 1902 Connolly returned to Edinburgh and helped launch the journal, Socialist, in Edinburgh. Connolly was influenced by the writings of the American radical Daniel DeLeon and published several articles by him in his journal.

Connolly emigrated to the United States in 1903. He established the Irish Socialist Federation and the newspaper, The Harp. In 1905 Connolly joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and worked hard at building up the movement in Newark, New Jersey. He also published several books including Socialism Made Easy (1909), Labour in Irish History (1910) and Labour, Nationality and Religion (1910).

In 1910 Connolly returned to Dublin where he joined the Socialist Party of Ireland. The following year William O'Brien arranged for Connolly to become organizer of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union in Belfast. In 1912 Connolly and James Larkin established the Irish Labour Party.

By 1913 the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union had 10,000 members and had secured wage increases for most of its members. Attempts to prevent workers from joining the ITGWU in 1913 led to a lock-out. Connolly returned to Dublin to help the union in its struggle with the employers. This included the formation of the Irish Citizen Army. Despite Larkin raising funds in England and the United States, the union eventually ran out of money and the men were forced to return to work on their employer's terms.

Connolly took control of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union when James Larkin left for a lecture tour of the United States in October 1914. He also revived his socialist journal, The Workers' Republic, but it was suppressed in February 1915. Later that year he published The Re-Conquest of Ireland (1915).

During the Easter Rising, Connolly's Irish Citizen Army fought alongside the Irish Volunteers under Patrick Pease. Connolly served in the General Post Office during the fighting and was severely wounded.

James Connolly was executed on the 12th of May 1916

On this day in 1945 Folke Bernadotte was asked by Heinrich Himmler to arrange peace talks with the Allies. Bernadotte, grandson of King Oscar II of Sweden, was born in Stockholm on 2nd January, 1895. After graduating from the military school of Karlberg, Bernadotte became a cavalry officer in the Royal Horse Guards.

Bernadotte became head of the Severiges Scoutforbund (Swedish Boy Scouts) and during the Second World War he integrated that organization into Sweden's defence system. He also served as vice chairman of the Swedish Red Cross and was responsible for arranging the exchange British and German soldiers during the war.

Bernadotte was fluent in six languages and carried out a great deal of important diplomatic work during the war. In early 1945 Bernadotte was asked to visit Heinrich Himmler, head of the Gestapo. The two men met in Lubeck on 24th April. Himmler asked Bernadotte to arrange a surrender that would allow Germany to continue fighting the Soviet Union. Bernadotte passed this information onto Winston Churchill and Harry S. Truman but the rejected the idea, insisting on unconditional surrender.

On 20th May, 1948, the United Nations Security Council appointed Bernadotte as mediator in the Arab-Jewish conflict in Palestine. After meeting Arab and Jewish leaders he succeeded in obtaining a 30-day truce that began on 11th June. In then developed his own plan for peace. This included the proposal that Israel should relinquish the Negev and Jerusalem to Transjordan. The plan was rejected by both sides and fighting resumed on 8th July, 1948.

On 17th September, 1948, Count Folke Bernadotte was assassinated by members of the Stern Group, a Jewish terrorist organization. His book, Instead of Arms, was published posthumously.

On this day in 1951 Elizabeth Bentley is criticised for glorifying treason and espionage. In 1944 Bentley left the Communist Party and the following year she considered telling the authorities about her spying activities. In August 1945 she was on holiday to Old Lyme. While in Connecticut she visited the FBI in New Haven. She was interviewed by Special Agent Edward Coady but she was reluctant to give any details of her fellow spies but did tell them that they she was vice-president of the U.S. Service and Shipping Corporation and the company was being used to send information to the Soviet Union. Coady sent a memo to the New York City office suggesting that Bentley could be used as an informant.

On 11th October 1945, Louis Budenz, the editor of the Daily Worker, announced that he was leaving the Communist Party of the United State and had rejoined "the faith of my fathers" because Communism "aims to establish tyranny over the human spirit". He also said that he intended to expose the "Communist menace". (38) Budenz knew that Bentley was a spy and four days later showed up at the FBI's New York office. Vsevolod Merkulov later wrote in a memo to Joseph Stalin that "Bentley's betrayal might have been caused by her fear of being unmasked by the renegade Budenz." (39) At this meeting she only gave the names of Jacob Golos and Earl Browder as spies.

Another meeting was held on the 7th November 1945. This time she gave the FBI a 107 page statement that named Victor Perlo, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Silvermaster, Abraham George Silverman, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Julian Wadleigh, William Remington, Harold Glasser, Charles Kramer, Duncan Chaplin Lee, Joseph Katz, William Ludwig Ullmann, Henry Hill Collins, Frank Coe, Abraham Brothman, Mary Price, Cedric Belfrage and Lauchlin Currie as Soviet spies. The following day J. Edgar Hoover, sent a message to Harry S. Truman confirming that an espionage ring was operating in the United States government. Some of these people, including White, Currie, Bachrach, Witt and Wadleigh, had been named by Whittaker Chambers in 1939.

There is no doubt that the FBI was taking her information very seriously. As G. Edward White, has pointed out: "Among her networks were two in the Washington area: one centered in the War Production Board, the other in the Treasury Department. The networks included two of the most highly placed Soviet agents in the government, Harry Dexter White in Treasury and Laughlin Currie, an administrative assistant in the White House." Amy W. Knight, the author of How the Cold War Began: The Ignor Gouzenko Affair and the Hunt for Soviet Spies (2005) has suggested that it had added significance because it followed the defection of Ignor Gouzenko.

As a result of Bentley's testimony the FBI returned to interview Whittaker Chambers: "From 1946 through 1948, special agents of the F.B.I., too, were frequent visitors. Usually, they were seeking information about specific individuals. For some time they were much interested in Victor Perlo, Harry Dexter White, Dr. Harold Glasser, Charles Kramer, John Abt and others. At that time, I had no way of knowing that they were checking a story much more timely than mine - that of Elizabeth Bentley. Most of these investigators went about their work in a kind of dogged frustration, overwhelmed by the vastness of the conspiracy, which they could see all around them, and depressed by the apathy of the country and the almost total absence in high places of any desire to root out Communism."

J. Edgar Hoover attempted to keep Bentley's defection a secret. The plan was for her to "burrow-back" into the Soviet underground in America in order to get evidence against dozens of spies. However, it was Hoover's decision to tell William Stephenson, the head of head of British Security Coordination about Bentley, that resulted in the Soviets becoming aware of her defection. Stephenson told Kim Philby and on 20th November, 1945, he informed NKVD of her betrayal. On 23rd November, Moscow sent a message to all station chiefs to "cease immediately their connection with all persons known to Bentley in our work and to warn the agents about Bentley's betrayal". The cable to Anatoly Gorsky told him to cease meeting with Donald Maclean, Victor Perlo, Charles Kramer and Lauchlin Currie. Another agent, Iskhak Akhmerov, was told not the meet with any sources connected to Bentley.

Attempts to establish connection with former Soviet agents ended in failure. Aware that they must know she was working with the FBI she began fearing that she would be murdered. After losing her job with the U.S. Service and Shipping Corporation she was desperately short of money. In August 1946, after what the FBI called "an exceptionally severe night of drinking" she took an overdose of phenobarbital. The FBI wanted her alive because she would be the major source against any future prosecutions. With the help of a FBI lawyer, Thomas J. Donegan, she was successfil in taking legal action against the U.S. Service and Shipping Corporation and she was awarded a year's salary in severance.

On 15th April, 1947, the FBI descended on the homes and businesses of twelve of the names provided by Bentley. Their properties were searched and they were interrogated by agents over several weeks. However, all of them refused to confess to their crimes. J. Edgar Hoover was eventually advised that the evidence provided by Elizabeth Bentley, Louis Budenz, Whittaker Chambers and Hede Massing was not enough to get convictions. Hoover's main concern now was to protect himself from charges that he had bungled the investigation.

On 30th July 1948, Elizabeth Bentley appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. The senators were relatively retrained in their questioning. They asked Bentley to mention only two names in public: William Remington and Mary Price. Apparently the reason for this was that Remington and Price had both been involved in Henry A. Wallace campaign. Bentley was also reluctant to give evidence against these people and made it clear that she was not sure if Remington knew his information was going to the Soviet Union. She also described spies such as Remington and Price as "misguided idealists".

The following day Bentley named several people she believed had been Soviet spies while working for the United States government. This included Victor Perlo, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Silvermaster, Duncan Chaplin Lee, Abraham George Silverman, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Donald Niven Wheeler, William Ludwig Ullmann, Julian Wadleigh, Harold Glasser, Henry Hill Collins, Frank Coe, Charles Kramer and Lauchlin Currie. One of the members of the HUAC, John Rankin, and well-known racist, pointed out the Jewish origins of these agents.

On 3rd August, 1948, Whittaker Chambers appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. He testified that he had been "a member of the Communist Party and a paid functionary of that party" but left after the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in August 1939. He explained how like Bentley he was involved in "the Communist infiltration of the American government." Chambers claimed his network of spies included several people named by Bentley. This included White, Currie, Silvermann, Witt, Collins and Kramer.

William Remington appeared before the Homer Ferguson Senate Committee. He admitted meeting Elizabeth Bentley but denied he helped her to spy. He claimed that Bentley had presented herself as a reporter for a liberal periodical. They had discussed the Second World War on about ten occasions but had never given her classified information. The committee did not find Remington's explanation persuasive, and neither did the regional loyalty board. The board soon recommended his dismissal from the government.

Elizabeth Bentley appeared before the NBC Radio's Meet the Press. One of the reporters asked her if William Remington was a member of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA)? She replied: "Certainly... I testified before the committee that William Remington was a communist." To preserve his credibility Remington sued both NBC and Bentley. On 15th December, 1948, Remington's lawyers served her with the libel papers. The libel suit was settled out of court shortly thereafter, with NBC paying Remington $10,000.

John Gilland Brunini, the foreman of the new grand jury investigating the charges made by Elizabeth Bentley, insisted that Ann Remington, who had divorced her husband, should appear before them. During interrogation by Bentley's lawyer, Thomas J. Donegan, Ann Remington admitted that William Remington was a member of the CPUSA and that he had provided Bentley with secret government documents. "Ann Remington was the first person from Elizabeth's espionage days who did not portray her as a fantasist and a psychopath." On 18th May, 1950, Elizabeth Bentley testified before the grand jury that Remington was a communist. When he stopped spying we "hated to let him go." The grand jury now decided to indict Remington for committing perjury.

William Remington's trial began in January 1951. Roy Cohn, joined the prosecution's legal team. He pointed out that the main witness against William Remington was his former wife, Ann Remington. She explained that her husband had joined the CP in 1937. Ann also testified that he had been in contact with both Elizabeth Bentley and Jacob Golos. "Elizabeth Bentley later supplied a wealth of detail about Remington's involvement with her and the espionage conspiracy. Remington's defense was that he had never handled any classified material, hence could not have given any to Miss Bentley. But she remembered all the facts about the rubber-from-garbage invention. We had searched through the archives and discovered the files on the process. We also found the aircraft schedules, which were set up exactly as she said, and inter office memos and tables of personnel which proved Remington had access to both these items. We also discovered Remington's application for a naval commission in which he specifically pointed out that he was, in his present position with the Commerce Department, entrusted with secret military information involving airplanes, armaments, radar, and the Manhattan Project (the atomic bomb)."

During the trial eleven witnesses claimed they knew Remington was a communist. This included Elizabeth Bentley, Ann Remington, Professor Howard Bridgeman of Tufts University, Kenneth McConnell, an Communist organizer in Knoxville, Rudolph Bertram and Christine Benson, who worked with him at the Tennessee Valley Authority and Paul Crouch who provided him with copies of the southern edition of the communist newspaper, the Daily Worker.

Remington was convicted after a seven-week trial. Judge Gregory E. Noonan handed down a sentence of five years - the maximum for perjury - noting that Remington's act of perjury had involved disloyalty to his country. One newspaper reported: "William W. Remington now joins the odiferous list of young Communist punks who wormed their way upward in the Government under the New Deal. He was sentenced to five years in prison, and he should serve every minute of it. In Russia, he would have been shot without trial."

Elizabeth Bentley decided to write her biography. She was aware that Louis Budenz had made a considerable amount of money of his book, This is My Story (1947), about his life as an uncover agent. Her book, Out of Bondage, was serialised in McCall's Magazine in June 1951. Some people objected to her making money from her crimes. Others complained that the articles glorified treason and espionage.

In the articles Bentley blamed her behaviour on Jacob Golos. She argued that she was under the dominant influence of her "husband". It has been argued by Kathryn S. Olmsted that "her self-constructed image helped to defect blame: she had, after all, done only what Yasha (Jacob Golos) had asked her to. How could she know it was wrong? She did certainly follow the lead of her lovers in political matters. Moreover, she had frequently allowed men to take advantage of her - though, ironically, Yasha treated her better than any of her other lovers."