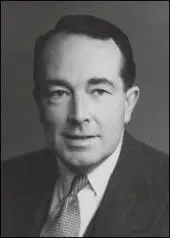

Hartley Shawcross

Hartley Shawcross was born in Germany on 4th February, 1902. His father, John Shawcross, was professor of English at Frankfurt University. His mother was related to the politician John Bright.

Soon after his birth John and Hilda Shawcross brought their son back to England. Shawcross took an early interest in politics and by the age of 16 he had joined the Labour Party and was ward secretary in Wandsworth. He was also involved in the party's campaign during the 1918 General Election.

A brilliant student, Shawcross decided to study French in Switzerland. While there he became translator to the British delegation at the Socialist International held in Geneva. He met Ramsay MacDonald and Herbert Morrison, who suggested that Shawcross should become a lawyer.

After obtaining a first class honours degree in law he moved to Liverpool. As well as working as a lawyer in the city he also lectured at the University of Liverpool (1927-34). Despite his left-wing views he was willing to work for the coal-owners during the court-case that followed the 1934 Gresford Colliery Disaster. Richard Stafford Cripps represented the miners.

During the Second World War Shawcross chaired the Enemy Aliens Tribunal (1939-41) and Deputy Regional Commissioner for the South-East (1941-42) and Commissioner for the North-West (1942-45).

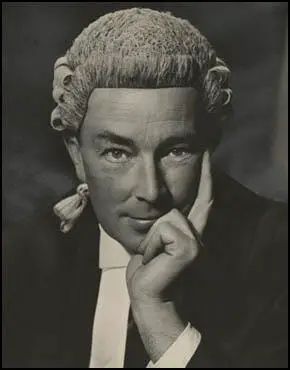

In the 1945 General Election Shawcross won with a large majority at St. Helens. The new prime minister, Clement Attlee, immediately appointed Shawcross as Britain's Attorney General. In this role he led the British prosecution at Nuremberg.

Shawcross also prosecuted William Joyce for high treason in September, 1945. In court it was stated that although he was United States citizen he had held a British passport during the early stages of the war. It was therefore argued in court by Shawcross that Joyce had committed treason by broadcasting for Nazi Germany between September 1939 and July 1940, when he officially became a German citizen. Joyce was found guilty of treason and was executed on 3rd January 1946.

Other famous prosecutions included the traitor John Amery, the Acid Bath Murderer, John George Haigh and the Atom bomb spy, Klaus Fuchs.

In the House of Commons Shawcross promoted the Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Bill, redressing anti-union legislation (the 1927 Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act) that was passed by a Conservative government following the 1926 General Strike. During the debate on this legislation Shawcross remarked: "We are the masters at the moment, and not only at the moment but for a very long time." He was much attacked for this and later he admitted it "was the most stupid thing I ever said."

In April 1951 Shawcross was appointed President of the Board of Trade. However, he lost office when the Labour Party lost the 1951 General Election. After this he concentrated on his lucrative law career and eventually retired from the House of Commons in 1958. When he became a life peer later that year he sat on the crossbenches of the House of Lords, although in the 1980s he supported the Social Democratic Party.

In later life Shawcross sat on the boards of a wide variety of different companies including Hawker Siddeley, Shell, EMI, Rank-Hovis-McDougall, Times Newspapers, Dominion Continental Bankers and Thames Television.

Hartley Shawcross, Lord Shawcross of Friston, died on 10th July, 2003.

Primary Sources

(1) Hartley Shawcross, opening statement at Nuremberg (4th December, 1945)

The British Empire with its Allies has twice, within the space of 25 years, been victorious in wars which have been forced upon it, but it is precisely because we realize that victory is not enough, that might is not necessarily right, that lasting peace and the rule of international law is not to be secured by the strong arm alone, that the British nation is taking part in this Trial. There are those who would perhaps say that these wretched men should have been dealt with summarily without trial by "executive action"; that their power for evil broken, they should have been swept aside into oblivion without this elaborate and careful investigation into the part which they played in bringing this war about: Vae Victis! Let them pay the penalty of defeat. But that was not the view of the British Government. Not so would the rule of law be raised and strengthened on the international as well as upon the municipal plane; not so would future generations realize that right is not always on the side of the big battalions; not so would the world be made aware that the waging of aggressive war is not only a dangerous venture but a criminal one.

Human memory is very short. Apologists for defeated nations are sometimes able to play upon the sympathy and magnanimity of their Victors, so that the true facts, never authoritatively recorded, become obscured and forgotten. One has only to recall the circumstances following upon the last World War to see the dangers to which, in the absence of any authoritative judicial pronouncement a tolerant or a credulous people is exposed. With the passage of time the former tend to discount, perhaps because of their very horror, the stories of aggression and atrocity that may be handed down; and the latter, the credulous, misled by perhaps fanatical and perhaps dishonest propagandists, come to believe that it was not they but their opponents who were guilty of that which they would themselves condemn. And so we believe that this Tribunal, acting, as we know it will act notwithstanding its appointment by the victorious powers, with complete and judicial objectivity, will provide a contemporary touchstone and an authoritative and impartial record to which future historians may turn for truth, and future politicians for warning. From this record shall future generations know not only what our generation suffered, but also that our suffering was the result of crimes, crimes against the laws of peoples which the peoples of the world upheld and will continue in the future to uphold by international co-operation, not based merely on military alliances, but grounded, and firmly grounded, in the rule of law.

Nor, though this procedure and this Indictment of individuals may be novel, is there anything new in the principles which by this prosecution we seek to enforce. Ineffective though, alas, the sanctions proved and showed to be, the nations of the world had, as it will be my purpose in addressing the Tribunal to show, sought to make aggressive war an international crime, and although previous tradition has sought to punish states rather than individuals, it is both logical and right that, if the act of waging war is itself an offense against international law, those individuals who shared personal responsibility for bringing such wars about should answer personally for the course into which they led their states. Again, individual war crimes have long been recognized by international law as triable by the courts of those states whose nationals have been outraged, at least so long as a state of war persists. It would be illogical in the extreme if those who, although they may not with their own hands have committed individual crimes, were responsible for systematic breaches of the laws of war affecting the nationals of many states should escape for that reason. So also in regard to Crimes against Humanity. The rights of humanitarian intervention on behalf of the rights of man, trampled upon by a state in a manner shocking the sense of mankind, has long been considered to form part of the recognized law of nations. Here too the Charter merely develops a pre-existing principle. If murder rapine, and robbery are indictable under the ordinary municipal laws of our countries, shall those who differ from the common criminal only by the extent and systematic nature of their offenses escape accusation?

It is, as I shall show, the view of the British Government that in these matters, this Tribunal will be applying to individuals, not the law of the victor, but the accepted principles of international usage in a way which will, if anything can, promote and fortify the rule of international law and safeguard the future peace and security of this war-stricken world.

(2) Hartley Shawcross attended the trial of the men charged with killing Vera Leigh, Diana Rowden, Andrée Borrel and Sonya Olschanezky.

The fearful cremations at Natzweiler had their counterpart a thousand times at Auschwitz. Hoess told us, 'The foul and nauseating stench from the continuous burning of bodies permeated the entire area and all the people living in the surrounding communities knew that exterminations were going on at Auschwitz.'

I do not recall these grim matters of the past for mere morbidity. I mention them as a reminder that the men convicted of the murder of Miss Andree Borrell, F.A.N.Y.; Section Officer Diana Rowden, W.A.A.F.; Miss Vera Leigh, F.A.N.Y., and another gallant woman, were not isolated, exceptional killings. These crimes were not sporadic or isolated, depending on the brutality of some individual sadist. They were a part of that system which arises when the totalitarian state submerges the fundamental right and destroys the dignity of man. Month by month, day after day, killings like these went on by the thousand all over Europe.

But the mind which is lastingly impressed and shocked by a single crime staggers and reels at the contemplation of mass criminality: becomes almost impervious to horror, conditioned against shock. And as events recede into the past, those who did not themselves experience them begin to question whether these things could indeed have happened and wonder whether the stories about them are really more than the propaganda of enemies.

(3) Adam Bernstein, Washington Post (11th July, 2003)

At Nuremberg, he worked alongside American Robert H. Jackson, a U.S. Supreme Court justice, and jurists from France and Russia.

In his opening address, Mr. Shawcross set a somber tone that emphasized the individual responsibility of the accused. "There comes a point," he said, "when a man must refuse to answer to his leader if he is also to answer to his conscience."

Movie-star dapper, Mr. Shawcross was once seen as a potential choice for Labor prime minister. But his legal eloquence occasionally yielded to public gaffes, including impolitic statements about newspapermen and British housewives. He also became increasingly disenchanted with his party's nationalization policies.

Many Liberals nicknamed him "Sir Shortly Floorcross" because of his apparent conservative sympathies during the Cold War. He preferred to call himself a "right-wing socialist."

(4) BBC News (10th July, 2003)

Controversial in public, Sir Hartley suffered tragedy in private. His first wife killed herself after years of illness, and his second wife died after being kicked by a horse on the Sussex Downs in 1974.

Into his 10th decade, he surprised his family by marrying a third time. His memoirs written then revealed a lifetime of personal unhappiness and disillusionment, but his prominence in the worlds of law, business and politics reveals an idealist surely determined to leave his mark.