On this day on 18th June

On this day in 1854 Edward Willis Scripps, the son of James Mogg Scripps, was born at Rushville, Illinois. His half-brother, James Edmund Scripps (1835-1906) started his own newspaper, The Detroit News in 1873. Scripps and his sister, Ellen Browning Scripps, were both employed on the newspaper.

In 1878 E. W. Scripps borrowed money from his brother and sister in order to produce The Penny Press in Cleveland. This newspaper was highly successful and by 1887 he also owned newspapers in St. Louis and Cincinnati.

Scripps' newspapers were aimed at a mass audience. In his autobiography, Damned Old Crank he argued: "I am one of the few newspapermen who happen to know that this country is populated by ninety-five per cent of plain people, and that the patronage of even plain and poor people is worth more to a newspaper owner than the patronage of the wealthy five per cent." His newspapers were low-priced and tended to support progressive causes and the trade union movement. He once wrote: "I have only one principle, and that is represented by an effort to make it harder for the rich to grow richer and easier for the poor to keep from growing poorer."

In one interview Scripps claimed that he viewed his newspapers as "the only schoolroom the working people had". He added "I am the advocate of that large majority of people who are not so rich in worldly goods and native intelligence as to make them equal, man for man, in the struggle with individuals of the wealthier and more intellectual class".

In 1894 Scripps joined with his half-brother, James Edmund Scripps, and Milton Alexander McRae, to form the Scripps-McRae League of Newspapers. Scripps now had a controlling interest in 34 newspapers in 15 different states.

Scripps founded the Newspaper Enterprise Association in 1902. This was the first syndicate to supply feature stories, illustrations and cartoons to newspapers. Five years later Scripps joined with others to form the news service, United Press International (UPI). Scripps later said "I regard my life's greatest service to the people of this country to be the creation of the United Press." Scripps' main objective was to provide competition to the Associated Press.

E. W. Scripps continued to work with his sister, Ellen Browning Scripps and in 1903 they joined together to found the Marine Biological Station in San Diego. She later established the Scripps College for Women in Claremont, California. E. W. Scripps also gave a lot of his money away: "The possessor of great wealth may be, and frequently is, corrupted. No matter how good and moral a man may be, the possession of great wealth must have a certain amount of corrupting influence upon him. The possession of great wealth isolates a man to a great extent from his fellows. This isolation results in a constantly diminishing sympathy for mankind."

Lincoln Steffens and Clarence Darrow met E. W. Scripps when he was 57 years old. Steffens later recalled "His (E. W. Scripps) hulking body, in big boots and rough clothes, carried a large grey head with a wide grey face which did not always express, like Darrow's, the constant activity of the man's brain. He was a hard student, whether he was working on newspaper make-up or some inquiry in biology. That mind was not to be satisfied. It read books and fed on the conversation of scientists, not to quench an inquiry with the latest information, but to excite and make intelligent the questions implied."

Throughout his career E. W. Scripps found that advertisers continually put him under pressure to drop his radical causes. He later recalled: "A newspaper fairly and honestly conducted in the interests of the great masses of the public must at all times antagonize the selfish interests of that very class (the advertisers) which furnishes the larger part of a newspaper's income. It must occasionally so antagonize this class as to cause it not only to cease patronage, to a greater or lesser extent, but to make actually offensive warfare against the newspaper."

In 1911 he decided to publish a newspaper that was completely free of advertising. The tabloid-sized newspaper was called The Day Book, and at a penny a copy, it aimed for a working-class market, crusading for higher wages, more unions, safer factories, lower streetcar fares, and women’s right to vote. It also tackled the important stories ignored by most other dailies. According to Duane C. S. Stoltzfus, the author of Freedom from Advertising (2007): "The Day Book served as an important ally of workers, a keen watchdog on advertisers, and it redefined news by providing an example of a paper that treated its readers first as citizens with rights rather than simply as consumers."

Carl Sandburg was one of the journalists employed on the newspaper. Dorothy Day was one of those who read the newspaper and later admitted that it informed her about people like Eugene Debs and organisations such as the Industrial Workers of the World: " Through the paper I learned of Eugene Debs, a great and noble labor leader of inspired utterance. There were also accounts of the leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World who had been organizing in their one great union so that there were a quarter of a million members throughout the wheatfields, mines, and woods of the Northwest, as well as in the textile factories in the East." Though the Day Book’s financial losses steadily declined over the years, it never became profitable, and publication ended in 1917.

E. W. Scripps told Lincoln Steffens: "I'm a rich man, and that's dangerous, you know. But it isn't just the money that's the risk; it's the living around with other rich men. They get to thinking all alike, and their money not only talks, their money does their thinking, too. I come off here (his San Diego ranch) on these wide acres of high miles to get away from - my sort; to get away from the rich. So I don't think like a rich man. They talk about the owner of newspapers holding back his editors. It's the other way with me. I get me boys, bright boys, from the classes that read my papers; I give them the editorship and the management, with a part interest in the property, and, say, in a year or so, as soon as the profits begin to come in, they become conservative and I have to boot them back into their class." In 1922 Scripps transferred his business interests to his son, Robert Paine Scripps (1895-1938), who three years later joined forces with Roy W. Howard (1883-1964), to form the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain.

Just before his death E. W. Scripps wrote: "To grow old sensibly, one should always keep one's eyes turned from the past to the future, and continue to strive with all his might to serve those who are coming even more efficiently than those he has served shoulder to shoulder with in the past."

Edward Willis Scripps died on 12th March, 1926. A collection of his unpublished writings, Damned Old Crank: A Self-Portrait of E.W. Scripps, was published in 1951.

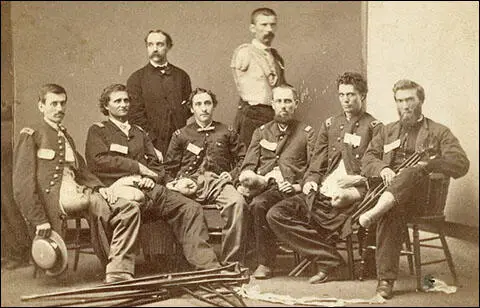

On this day in 1863 Walt Whitman writes in his diary about nursing wounded soldiers in the American Civil War.

In one of the hospitals I find Thomas Haley, company M, 4th New York cavalry. A regular Irish boy, a fine specimen of youthful physical manliness, shot through the legs, inevitably dying. Came over to this country from Ireland to enlist. Is sleeping soundly at this moment (but it is the sleep of death). Has a bullet-hole through the lung. I saw Tom when first brought here, three days since, and didn't suppose he could live twelve hours. Much of the time he sleeps, or half sleeps. I often come and sit by him in perfect silence; he will breathe for ten minutes as softly and evenly as a young babe asleep. Poor youth, so handsome, athletic, with profuse beautiful shining hair. One time as I sat looking at him while he lay asleep, he suddenly, without the least start, awakened, opened his eyes, gave me a long steady look, turning his face very slightly to gaze easier, one long, clear, silent look, a slight sigh, then turned back and went into his doze again.

In one bed a young man, Marcus Small, company K, 7th Maine. Sick with dysentery and typhoid fever. Pretty critical case, I talk with him often. He thinks he will die, looks like it indeed. I write a letter for him to East Livermore, Maine. I let him talk to me a little, but not much, advise him to keep very quiet. Do most of the talking myself, stay quite a while with him, as he holds on to my hand.

Opposite, an old Quaker lady sits by the side of her son, Amer Moore, 2nd U.S. Artillery. Shot in the head two weeks since, very low, quite rational, from hips down paralyzed, he will surely die. I speak a very words to him every day and evening. He answers pleasantly, wants nothing. He told me soon after he came about his home affairs, his mother had been an invalid, and he feared to let her know his condition. He died soon after she came.

On this day in 1877 Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh in court for publishing book on birth control. They were prosecuted by the Solicitor-General of the Conservative government, Hardinge Giffard, for publishing "a certain indecent, lewd, filthy, bawdy, and obscene book". They were to be charged under the 1857 Obscene Publications Act that stated that "the test of obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall."

Giffard argued: "The truth is, those who publish this book must have known perfectly well that an unlimited publication of this sort, put into the hands of everybody, whatever their age, whatever their condition in life, whatever their modes of life, whatever their means, put into the hands of any person who may think proper to pay sixpence for it - the thesis is this: if you do not desire to have children, and wish to gratify your sensual passions, and not undergo the responsibility of marriage... It is sought to be justified upon the ground that it is only a recommendation to married people, who under the cares of their married life are unable to bear the burden of too many children. I should be prepared to argue before you that if confined to that object alone it would be most mischievous.... I deny this, and I deny that it is the purport and intention of this book."

Annie Besant replied:

It is not as defendant that I plead to you today - not simply as defending myself do I stand here but I speak as counsel for hundreds of the poor, and it is they for whom I defend this case. My clients are scattered up and down through the length and breadth of the land; I find them amongst the poor, amongst whom I have been so much; I find my clients amongst the fathers, who see their wage ever reducing, and prices ever rising; I find my clients amongst the mothers worn out with over-frequent child-bearing, and with two or three little ones around too young to guard themselves, while they have no time to guard them. It is enough for a woman at home to have the care, the clothing, the training of a large family of young children to look to; but it is a harder task when oftentimes the mother, who should be at home with her little ones, has to go out and work in the fields for wage to feed them when her presence is needed in the house.

I find my clients among the little children. Gentlemen, do you know the fate of so many of these children? The little ones half starved because there is food enough for two but not enough for twelve; half clothed because the mother, no matter what her skill and care, cannot clothe them with the money brought home by the breadwinner of the family; brought up in ignorance, and ignorance means pauperism and crime - gentlemen, your happier circumstances have raised you above this suffering but on you also this question presses; for these overlarge families mean also increased poor rates, which are growing heavier year by year. These poor are my clients... mothers who beg me to persist in the course on which I have entered - and at any hazard to myself, at any cost and any risk - they plead to me to save their daughters from the misery they have themselves passed through during the course of their married lives...

I will only put it to you now, that you have got before you a great social question which is becoming more and more pressing as every year goes by.... It is a fact that the object of this pamphlet, so far from destroying marriage and so far from approving any kind of illicit connection between the sexes - it is a fact that the pamphlet is written by Dr Knowlton, and circulated by us today, for the purpose which the learned judge suggested was a question of great importance, that of making early marriage possible to a very large number of young men today. Our object is not to destroy marriage but to make it more widely prevalent; not to encourage prostitution, but to destroy that which is a very prolific source of prostitution, the shrinking of young men from marriage because of the terrible responsibility that marriage often brings with it. That is the object of my co-defendant and myself...

I put it to you that there is nothing wrong in a natural desire rightly and properly gratified. There is no harm in feeling thirsty because people get drunk; there is no harm in feeling hungry because people over-eat themselves, and there is no harm in gratifying the sexual instinct if it can be gratified without injury to anyone else, and without harm to the morals of society, and with due regard to the health of those whom nature has given us the power of summoning into the world. I put it to you gravely, that it is only a false and spurious kind of modesty, which sees harm in the gratification of one of the highest instincts of human nature - an instinct which goes through all the world, not only in the animal but in the vegetable kingdom; if you are to blame Dr Knowlton because he recognises a great natural fact, then it is your duty to blame the constitution of the world, and the arrangements of nature, because you find that the reproductive instinct is attended with pleasure in its due gratification...

And I may say here, too, that Dr Knowlton remarks that "mankind will not so abstain"; as a simple matter of fact, I must put it to you that men and women, but more especially men, will not lead a celibate life, whether they are married or unmarried, and that what you have got to deal with is, that which we advocate early marriage with restraint upon the numbers of the family or else a simple mass of unlicensed prostitution, which is the ruin of both men and women when once they fall into it.

On this day in 1882 Georgi Dimitrov was born in Kovachevtsi, Bulgaria. His father, a Macedonian, forced to flee from his home at the time of the Turkish massacres.

At the age of 12 he became a compositor in the printing industry and four years later helped form the Printers Union. Dimitrov joined the Bulgarian Social Democratic Party and soon became one of its leading left-wing members. In 1913 he was elected to the Bulgarian Parliament as a socialist.

Dimitrov campaigned against the country's involvement in the First World War. This led to him being imprisoned for sedition and he was held in captivity without trial for over two years.

In 1919 Dimitrov helped form the Bulgarian Communist Party. However, after the general election in October, 1919, Aleksandar Stamboliyski, the leader of the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union, became prime minister. His election was unpopular with the ruling class and was murdered during a military coup on 9th June, 1923. Stamboliyski was replaced by Aleksandar Tsankov, who attempted to crush left-wing political groups. In 1924 Dimitrov managed to escape to the Soviet Union and received a death sentence in absentia.

After the Russian Revolution leading members of the Communist Party founded the Communist International (later known as Comintern). The aim of the organization was to fight "by all available means, including armed force, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie and for the creation of an international Soviet republic as a transition stage to the complete abolition of the State". Lenin believed that to create the "foundations of the international Communist movement" was more important "than to conquer just Russia for the Revolution".

Gregory Zinoviev, was elected chairman of the Comintern and one of his recruits was Georgi Dimitrov. Over the next few years he used various pseudonyms to travel around Europe helping to promote communist revolution. This included Vienna and in 1929 Dimitrov moved to Berlin. His main task was to support the German Communist Party (KPD). According to Roy A. Medvedev, this involved undermining other left-wing, non-revolutionary groups, such as the Social Democratic Party (SDP).

In the General Election of November 1932, the KPD won 100 seats in the Reichstag. The SDP did slightly better with 121 seats but it was the Nazi Party with 196, that had the greatest success. However, when Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor, in January 1933, the Nazis only had a third of the seats in Parliament.

On 27th February, 1933, the Reichstag building caught fire. It was reported at ten o'clock when a Berlin resident telephoned the police and said: "The dome of the Reichstag building is burning in brilliant flames." The Berlin Fire Department arrived minutes later and although the main structure was fireproof, the wood-paneled halls and rooms were already burning.

Hermann Göring, who had been at work in the nearby Prussian Ministry of the Interior, was quickly on the scene. Hitler and Joseph Goebbels arrived soon after. So also did Rudolf Diels, who was later to become the head of the Gestapo: "Shortly after my arrival in the burning Reichstag, the National Socialist elite had arrived. On a balcony jutting out of the chamber, Hitler and his trusty followers were assembled." Göring told him: "This is the beginning of the Communist Revolt, they will start their attack now! Not a moment must be lost. There will be no mercy now. Anyone who stands in our way will be cut down. The German people will not tolerate leniency. Every communist official will be shot where he is found. Everybody in league with the Communists must be arrested. There will also no longer be leniency for social democrats."

Hitler gave orders that all leaders of the German Communist Party (KPD) should "be hanged that very night." Paul von Hindenburg vetoed this decision but did agree that Hitler should take "dictatorial powers". Orders were given for all KPD members of the Reichstag to be arrested. This included Ernst Torgler, the chairman of the KPD. Göring commented that "the record of Communist crimes was already so long and their offence so atrocious that I was in any case resolved to use all the powers at my disposal in order ruthlessly to wipe out this plague".

Marinus van der Lubbe had been arrested in the building. He was a 24 year-old vagrant. He was born in Leiden, on 13th January, 1909. His father was a heavy drinker who left the family when he was seven years old. His mother died five years later. He was then raised by an older sister and was brought up in extreme poverty. After leaving school Lubbe worked as a bricklayer but after an industrial accident in 1925 he spent five months in hospital. He never fully recovered from his injuries and was now unable to work and had to live on a small invalidity pension. He joined the Communist Party of the Netherlands and in 1933 moved to Germany.

Van der Lubbe denied that he was part of a Communist conspiracy and had no connections with the SDP or the KPD. He insisted that he acted alone and the burning of the Reichstag was his own idea. He went on to claim, "I do nothing for other people, all for myself. No one was for setting the fire." However, he hoped that his act of arson would lead the revolution. "The workers should rebel against the state order. The workers should think that it is a symbol for a common uprising against the state order." Hermann Göring, who was in control of the investigation, ignored what van der Lubbe had said and on 28th February, he made a statement stating that he had prevented a communist uprising.

On 3rd March, Lubbe made a full confession: "I myself am a Leftist, and was a member of the Communist Party until 1929. I had heard that a Communist demonstration was disbanded by the leaders on the approach of the police. In my opinion something absolutely had to be done in protest against this system. Since the workers would do nothing, I had to do something myself. I considered arson a suitable method. I did not wish to harm private people but something belonging to the system itself. I decided on the Reichstag. As to the question of whether I acted alone, I declare emphatically that this was the case."

Göring refused to believe this story and urged Detective-Inspector Walter Zirpins, who was leading the investigation, to find evidence that the Reichstag Fire was the result of a communist conspiracy. After the government promised a 20,000 marks to anyone who provided information that led to a conviction in the case, Zirpins received a call from a waiter, Johannes Helmer, who worked at the Bayernhof Restaurant. Helmer claimed that he had seen Van der Lubbe with three foreigners in the restaurant.

The other eight waiters at the restaurant disagreed with Helmer but he continued to insist he was right: "In my opinion this man (Marinus van der Lubbe) is certainly one of the guests who repeatedly came into the cafe with the Russians. All of them struck me as suspicious characters, because they spoke in a foreign language, and because they all dropped their voices whenever anyone went past their table."

Helmer was told to contact the police the next time the three men returned to the restaurant. This happened on 9th March and the three men, Georgi Dimitrov, Blagoi Popov and Vassili Tanev, were arrested. A journalist, Ernst Fischer, was also in the restaurant at the time: "Round the table sat a big, broad-shouldered man (Dimitrov) with a dark, lion's mane, and two younger men, slighter in build and less striking in appearance. The detective asked them to come along. The big, broad-shouldered man produced his papers."

The men were carrying false papers but the police soon discovered that the documents had been produced at a shop linked to the KPD. When they went to their lodgings they found communist leaflets. After further questioning the men admitted that they were Bulgarians rather than Russians. However, the police still not realise that Dimitrov was the head of the Central European section of Comintern and one of the most important figures in the "international Communist movement".

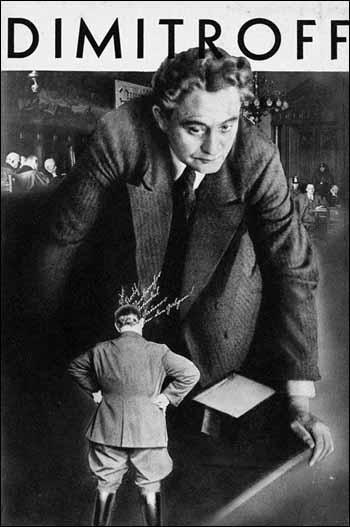

Georgi Dimitrov, Marinus van der Lubbe, Ernst Torgler, Blagoi Popov and Vassili Tanev were indicted on charges of setting the Reichstag on fire. The trial began on 21st September, 1933. The presiding judge was Judge Dr. Wilhelm Bürger of the Supreme Court. The accused were charged with arson and with attempting to overthrow the government.

Douglas Reed, a journalist working for The Times, described the defendants in court. "A being (Marinus van der Lubbe) of almost imbecile appearance, with a shock of tousled hair hanging far over his eyes, clad in the hideous dungarees of the convicted criminal, with chains around his waist and wrists, shambling with sunken head between his custodians - the incendiary taken in the act. Four men in decent civilian clothes, with intelligence written on every line of their features, who gazed somberly but levelly at their fellow men across the wooden railing which symbolized the great gulf fixed between captivity and freedom.... Torgler, last seen by many of those present railing at the Nazis from the tribune of the Reichstag, bore the marks of great suffering on his fine and sensitive face. Dimitrov, whose quality the Court had yet to learn, took his place as a free man among free men; there was nothing downcast in his bold and even defiant air. Little Tanev had not long since attempted suicide, and his appearance still showed what he had been through, Popov, as ever, was quiet and introspective."

Georgi Dimitrov constantly passed comments on proceedings. Fritz Tobias has commented: "The great pomp with which the trial was conducted did not impress Dimitrov for a single moment. His intelligence was razor-sharp and, unlike his two compatriots, he had a good command of the German language, and was therefore able to expose the prosecution's case for the sham it was."

Dimitrov was first expelled for the first time on 6th October 1933. According to foreign press, he was ejected for "quite inexplicable reasons" or "on a ridiculous pretext". He was actually removed for accusing the Gestapo for adding a cross over the Reichstag on a map he had purchased. The judge ruled that he had been taken from the court "for disobeying repeated admonitions to desist from insulting police officers".

Dimitrov persistently refused to allow his Government-nominated counsel, Dr Teichert, to act on his behalf. On 12th October he was expelled from the court once again. In a letter to Judge Dr. Wilhelm Bürger he pointed out that the German Supreme Court had rejected every one of the eight lawyers he had selected. Therefore, he argued: "I had no option but to defend myself as best I could. As a result I have been compelled to appear in Court in a double capacity: first as Dimitrov, the accused, and second as the defender of the accused Dimitrov."

At this time, the German government, had not taken full control of the court system. Judge Bürger held conservative views and was a member of the right-wing, German National People's Party (DNVP), "for all his political prejudices, was a lawyer of the old school, and stuck to the rules." Bürger was so impressed with Dimitrov's letter he gave permission for him to represent himself in court. Something he did with "ingenuity and skill".

Dimitrov became the "hero" of the trial. "Dimitrov... was always polite and courteous, but the attacks on the Nazis and his comments on the judges and the manner in which they were conducting the trial were sharp, bitter and ironic. On one occasion he would declare that the verdict of the trial was already fixed, and not by the court. On another occasion, he accused the Nazis themselves of setting the Reichstag on fire."

The indictment against Dimitrov read: "Although Dimitrov was not caught red-handed at the scene of the crime, he nevertheless tock part in the preparations for the burning of the Reichstag. He went to Munich in order to supply himself with an alibi. The Communist pamphlets found in Dimitrov's possession prove that he took part in the Communist movement in Germany...The charge rests on the basis that this criminal outrage was to be a signal, a beacon for the enemies of the State who were then to launch their attack on the German Reich, to destroy it and to set up in its place a dictatorship of the proletariat, a Soviet State, at the orders of the Third International."

Professor Emile Josse, lecturer on thermodynamics at the Berlin Technical College, argued in court that van der Lubbe could not have set fire to the Reichstag on his own. Dimitrov, commented: "I am glad that the experts too are of the opinion that van der Lubbe could not have acted all by himself. This is the only point in the indictment with which I am in complete accord... I wish once more and for the last time to ask van der Lubbe. As was already said, he was not alone. His conduct, his silence makes it possible for innocent people to be accused along with him. I would not ask van der Lubbe about his accomplices, had his act been revolutionary, but it is counter-revolutionary." Van der Lubbe refused to answer.

Van der Lubbe admitted that he had made three failed attempts at arson on 25th February in different buildings in Berlin. Dimitrov asked van der Lubbe: "Why were you unable to set fire to the small charity institution, yet managed to set fire to the large stone building of the Reichstag, and in just a quarter of an hour at that?... The Communist International demands full clarity on the question of the Reichstag fire. Millions are waiting for an answer!"

Georgi Dimitrov was also allowed to cross-examine Hermann Göring in court. Göring kept his expectant audience waiting and arrived over an hour late: "Göring entered the room in the brown uniform, leather belt and top boots of an S.A. leader. Everyone jumped up as if electrified, and all Germans, including the judges, raised their arms to give the Hitler salute."

Dimitrov's first question concerned an interview on 28th February, 1933, where he claimed that when van der Lubbe was arrested, he had a German Communist Party membership card in his pocket. He asked Göring how he knew this? He replied: "I do not run about or search the pockets of people. If this should still be unknown to you, let me tell you: the police examines all great criminals and informs me of its findings". Dimitrov then shocked the court by claiming: "The three officials of the criminal police who arrested and first interrogated van der Lubbe unanimously declared that no membership card was found on Lubbe. From where has the information about the card come then, I should like to know?"

Dimitrov then went on to ask Göring why he immediately announced that it was Communists who had set the Reichstag on fire: "After you, as Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior, had declared that the incendiaries were Communists, that the German Communist Party had committed the crime with the aid of van der Lubbe as a foreign Communist, did this declaration on your part not serve to direct the police inquiry and afterwards - the Court investigations in a certain direction, excluding the possibility of looking for other ways and means of finding the true incendiaries of the Reichstag?"

Göring replied: "The criminal police will investigate all traces, be sure of it. I had only to establish: was this a crime beyond the political sphere or was it political in character. For me it was a political crime and I was also convinced that the criminals had to be looked for in your Party". He then shook his fists at Dimitrov and shouted. "Your Party is a Party of criminals, which must be destroyed! And if the hearing of the Court has been influenced in this sense, it has set out on the right track.... the German people know that here you are behaving insolently, that you have come here to set fire to the Reichstag. But I am not here to allow you to question me like a judge and to reprimand me! In my eyes you are a scoundrel who should be hanged." Dimitrov's questioning of Göring was considered so successful that he was expelled from the court for three days. (28)

Georgi Dimitrov returned on the 8th October and was now allowed to cross-examine Joseph Goebbels. He obviously agreed to this as he was confident that he was clever enough to deal with Dimitrov. He was asked: "Does the witness, both as head of the National Socialist Party propaganda and as Propaganda Reichsminister, know whether it is true that the setting on fire of the Reichstag was immediately used by the Government and the Propaganda Ministry as a pretext to stifle the electoral campaign of the Communist Party, the Socialist and other opposition parties?"

Goebbels replied: "I must explain the following: the necessary measures were taken by the police. We did not need to use any propaganda, because the Reichstag fire was actually only a confirmation of our struggle against the Communist Party and we could merely add the burning of the Reichstag to the collection of adequate proofs against the Communist Party as a new evidence, there being no need to launch a special propaganda campaign."

Dimitrov then asked the killer question: "Did not he himself deliver a speech broadcast over the radio, branding the Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party as authors of the Reichstag fire? Not only against the Communist Party but also against the Social Democratic Party?" Dimitrov's purpose in asking the question was quite clear. If Goebbels now admitted he had been wrong about the Social Democrats, might he not have been equally wrong about the Communists?

Goebbels replied: "When we accused the Communist Party of being the instigator of the Reichstag fire, the continuous line from the Communist Party to the Social Democratic Party was immediately apparent; because we do not share the bourgeois viewpoint that there is a fundamental difference between the Social Democratic and the Communist Party - something which is confirmed by the German politics of fourteen years. For us there was a difference between these two organizations only in tactics, only in the pace, but not in the principles, nor in the basic positions. When, therefore, we accused Marxism in general and its most acute form - Communism, of intellectual instigation, and maybe even of practical implementation of the Reichstag fire, then this attitude by itself meant that our national task was to destroy, to wipe off the face of the earth the Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party."

Dimitrov then suggested that the Nazi Party agreed with violence if it was used against left-wing activists. He mentioned the deaths of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht: "Is it true that the National Socialist Government has granted a pardon to all terrorist acts carried out to further the aims of the National Socialist movement?" Goebbels replied that: "The National Socialist Government could not leave in prisons people who, risking their lives and health, had fought against the Communist peril."

On 16th December, 1933, Georgi Dimitrov was allowed to make his final speech to the court. "I am defending myself, an accused Communist. I am defending my political honour, my honour as a revolutionary. I am defending my Communist ideology, my ideals. I am defending the content and significance of my whole life. For these reasons every ward which I say in this Court is a part of me, each phrase is the expression of my deep indignation against the unjust accusation, against the putting of this anti-Communist crime, the burning of the Reichstag, to the account of the Communists."

Dimitrov talked about previous attempts to use forged documents to accuse left-wing activists of attempting to cause revolutions. This included the case of the Zinoviev Letter. In September 1924 MI5 intercepted a letter signed by Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern in the Soviet Union, and Arthur McManus, the British representative on the committee. In the letter British communists were urged to promote revolution through acts of sedition. The publication of the letter in the Daily Mail helped to bring down Ramsay MacDonald, and the Labour government.

Dimitrov explained: "I should like also for a moment to refer to the question of forged documents. Numbers of such forgeries have been made use of against the working class. Their name is legion. There was, for example, the notorious Zinoviev letter, a letter which never emanated from Zinoviev, and which was a deliberate forgery. The British Conservative Party made effective use of the forgery against the working class."

Another aspect of his speech dealt with the funding of the Nazi Party. He claimed that industrialists such as Alfried Krupp and Fritz Thyssen, had provided money to Adolf Hitler in order to produce legislation that was hostile to trade unions. "This struggle taking place in the camp of the National Front was connected with the behind-the-scenes struggle in Germany's leading economic circles. On the one hand was the Krupp-Thyssen circle (the war industry), which for many years past has supported the National Socialists; on the other hand, being gradually pushed into the background, were their opponents. Thyssen and Krupp wished to establish the principle of absolutism, a political dictatorship under their own personal direction and to substantially depress the living standards of the working class; it was to this end that the crushing of the revolutionary working class was necessary."

Dimitrov also attacked his fellow defendant, Marinus van der Lubbe: "What is van der Lubbe? A Communist? Inconceivable. An Anarchist? No. He is a declassed worker, a rebellious member of the scum of society. He is a misused creature who has been played off against the working class. No, he is neither a Communist nor an Anarchist. No Communist, no Anarchist anywhere in the world would conduct himself in Court as van der Lubbe has done. Genuine Anarchists often do senseless things, but invariably when they are haled into Court they stand up like men and explain their aims. If a Communist had done anything of this sort, he would not remain silent knowing that four innocent men stood in the dock alongside him. No, van der Lubbe is no Communist. He is no Anarchist; he is the misused tool of fascism."

On 23rd December, 1933, Judge Wilhelm Bürger announced that Marinus van der Lubbe was guilty of "arson and with attempting to overthrow the government". Bürger concluded that the German Communist Party (KPD) had indeed planned the fire in order to start a revolution, but the evidence against Georgi Dimitrov, Ernst Torgler, Blagoi Popov and Vassili Tanev, was insufficient to justify a conviction.

After his release Georgi Dimitrov moved to Paris where he joined up with Willi Münzenberg, a leading figure in the KPD. Münzenberg had established the World Committee Against War and Fascism. The group, that included people such as Heinrich Mann, Charlotte Despard, Sylvia Pankhurst, Ellen Wilkinson, Vera Brittain, Storm Jameson, Ella Reeve Bloor, John Strachey, Norman Angell and Sherwood Anderson, established an investigation into the Reichstag Fire.

Münzenberg arranged for the publication of the book, The Brown Book of the Hitler Terror and the Burning of the Reichstag. With a cover designed by John Heartfield, the book argued that Hermann Göring was responsible for the Reichstag Fire. The historian A. J. P. Taylor, has pointed out: "Münzenberg and his collaborators were a jump ahead of the Nazis. Not only had they the evidence of the experts, demonstrating that van der Lubbe could not have done it alone and therefore implicating the Nazis; they also produced a mass of evidence to show how the Nazis had done it. The vital point here was an underground passage from Göring’s house to the Reichstag, which carried electric and telephone cables and pipes for central heating. Through this passage some S.A. men (Brown Shirts) were supposed to have entered the Reichstag."

Münzenberg became the key figure in propaganda campaign that attempted to show that Adolf Hitler was behind the burning of the Reichstag. "He (Münzenberg) organized the Reichstag Counter-Trial - the public hearings in Paris and London in 1933, which first called the attention of the world to the monstrous happenings in the Third Reich. Then came the series of Brown Books, a flood of pamphlets and newspapers which he financed and directed, though his name nowhere appeared."

The name of Otto Katz appeared on the cover of The Brown Book of the Hitler Terror and the Burning of the Reichstag. However, it was the work of a small group of communist journalists. Alfred Kantorowicz was one of those involved in producing the booklet: "The world at large learned of the history of this fire and of the true incendiaries from the Brown Book of the Hitler Terror and the Burning of the Reichstag, which contained a complete and irrefutable body of evidence."

The book included a document that became known as the Oberfohren Memorandum. Published in April 1933, it was claimed to have been written by Ernst Oberfohren, the Parliamentary leader of the German National People's Party (DNVP). The document stated that Hermann Göring and Edmund Heines, had organized the Reichstag fire. "The agents of Herr Göring, led by the Silesian S.A. leader, Reichstag-deputy Heines, entering the Reichstag through the heating-pipe passage leading from the palace of the President of the Reichstag, Göring. Every S.A. and S.S. leader was carefully selected and had a special station assigned to him. As soon as the outposts in the Reichstag signalled that the Communist deputies Torgler and Koenen had left the building, the S.A. troop set to work."Oberfohren was unable to confirm the authenticity of the document as he had committed suicide on 7th May, 1933.

Another document published in the book was a letter signed by Karl Ernst, a leading figure in the Sturmabteilung (SA). He confessed that on the orders of Göring and Wolf von Helldorf, he along with Edmund Heines, had helped to set fire to the Reichstag. "Helldorf told me that the idea was to find ways and means of smashing the Marxists once and for all". "We spent hours settling all the details. Heines, Helldorf and I would start the fire on the 25th February, eight days before the election. Göring promised to supply incendiary material of a kind that would be extremely effective yet take up very little space."

Ernst went on to point out: "A few days before the fixed date, Helldorf told us that a young fellow had turned up in Berlin of whom we should be able to make good use. This fellow was the Dutch Communist van der Lubbe. I did not meet him before the action. Helldorf and I fixed all the details. The Dutchman would climb into the Reichstag and blunder about conspicuously in the corridor. Meanwhile I and my men would set fire to the Session Chamber and part of the lobby. The Dutchman was supposed to start at 9 o'clock - half an hour later than we did.... Van der Lubbe was to be left in the belief that he was working by himself."

Karl Ernst said that he had signed this document on 3rd June, 1934, because he feared for his life. "I am doing so on the advice of friends who have told me that Göring and Goebbels are planning to betray me. If I am arrested, Göring and Goebbels must be told at once that this document has been sent abroad. The document itself may only be published on the orders of myself or of the two friends who are named in the enclosure, or if I die a violent death." Ernst was in fact executed on 30th June, 1934, as part of the Night of the Long Knives.

Georgi Dimitrov returned to the Soviet Union and Joseph Stalin, who had been very impressed with his performance at the Reichstag Fire, appointed him as head of the Comintern. In 1935, at the 7th Comintern Congress, Dimitrov spoke for Stalin when he advocated the Popular Front strategy. Up until then socialist and liberal parties were denounced as "social fascists". Now they were "proclaimed to be desirable allies, to be wooed and joined in common struggle against the fascist danger, against the threatening alliance of Germany, Japan, and Italy."

In his speech Dimitrov argued that with the rise of Adolf Hitler the "formation of a joint People's Front providing for joint action with social democratic parties is a necessity". He added that it was vital that "we endeavour to unite the communist, social democratic, Catholic and other workers". He compared the Popular Front movement with the ancient tale of the capture of Troy: "The attacking army was unable to achieve victory until, with the aid of the Trojan Horse, it penetrated to the very heart of the enemy camp. We, revolutionary workers, should not be shy of using the same tactics."

This strategy was employed during the Spanish Civil War. Dimitrov was in favour of the formation of International Brigades. These were volunteer international legions that would fight on the side of the Republican Army. One of these legions was named the Dimitrov Battalion. It was composed of Czech, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Rumanian and Yugo-Slavian troops". The battalion took part in several battles including the offensive at Jarama in February 1937. One of its commanders was Josip Tito, who later became ruler of Yugoslavia.

Stalin began to grow concerned about the supporters of Leon Trotsky fighting in the war against fascism in Spain. Alexander Orlov and his NKVD agents had the unofficial task of eliminating the Trotskyites fighting for the Republican Army and the International Brigades. This included the arrest and execution of leaders of the Worker's Party (POUM), National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI). Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996) has pointed out: "Stalin had a secret and extremely important aim in Spain: to eliminate the supporters of Trotsky who had gathered from all over the world to fight for the Spanish revolution. NKVD men, and Comintern agents loyal to Stalin, accused the Trotskyists of espionage and ruthlessly executed them."

Georgi Dimitrov, who for a long time had been an advocate of world revolution, was also investigated. The NKVD put together a special file against Dimitrov but he was never arrested. Stalin told him that "all of you in the Comintern are hand in glove with the enemy". However, many of his friends were put on trial during the Great Purge. "Scores of functionaries in its Executive Committee as well as its various departments were executed."

Dimitrov's two comrades, Blagoi Popov and Vassili Tanev, who had been charged with the Reichstag Fire, were also arrested. When he appealed on behalf of the two men, Stalin shrugged: "What can I do for them, Georgi? All my own relatives are in prison too."

In January, 1937, Yuri Piatakov, Karl Radek, Grigori Sokolnikov, and several other leading members of the Communist Party were put on trial. They were accused of working with Trotsky in an attempt to overthrow the Soviet government with the objective of restoring capitalism. Lion Feuchtwanger, the German writer, went to see Georgi Dimitrov and informed him "that people took a very hostile view of this trial, and that nobody would believe that fifteen high-principled revolutionaries, who had so often risked their lives by participating in conspiracies." It was said that "Dimitrov was very agitated when talking about this" but was unable to "convince him" that these men were guilty.

After the occupation of Bulgaria by the Red Army in September 1944, Georgi Dimitrov returned to his home land and took over the leadership of the Bulgarian Communist Party. A one-party state was established and Dimitrov was made Premier of Bulgaria on 6th November, 1946.

Dimitrov started negotiating with Josip Tito, the communist leader of Yugoslavia, about the creation of a Federation of the Southern Slavs. The idea eventually resulted in the Bled Accord, signed by Dimitrov and Tito on 1st August 1947. The agreement called for abandoning frontier travel barriers and arranging for a future customs union.

Joseph Stalin did not like the idea of the two communist leaders exerting their independence. It is believed that Stalin sent out agents to kill the two men. Tito sent a note to Stalin that said: "Stalin: stop sending people to kill me. We've already captured five of them, one of them with a bomb and another with a rifle... If you don't stop sending killers, I'll send one to Moscow, and I won't have to send a second."

Georgi Dimitrov died after a short illness on 2nd July, 1949, in a sanatorium near Moscow. Some historians have raised the issue that Dimitrov was poisoned. Simon Sebag Montefiore has pointed out that Stalin arranged for several of his opponents to die while being treated for different medical conditions.

Milovan Djilas has argued: Dimitrov.... belonged to that class of Bulgarians - the best of their race - in whom rebellion and self-confidence fuse in an indestructible essence. He must at least have suspected that the Soviet attack on Yugoslavia would entail the subjugation of Bulgaria, and that the realization of his youthful dream of unification with Serbia would be projected into the misty future, thereby reopening the yawning gulf of Balkan conflicts, and unleashing a tumultuous flood of Balkan claims. Today, after so many years, I still think that even though Dimitrov was ailing and diabetic, he did not die a natural death in the Borvilo clinic outside Moscow. Stalin was wary of self-confident personalities, especially if they were revolutionaries, and he was far more interested in Balkan hatreds than in Balkan reconciliations."

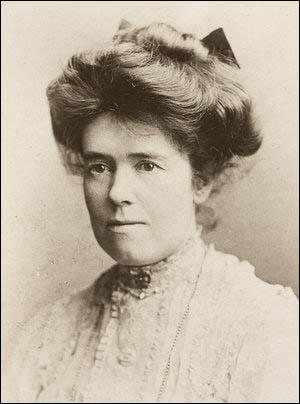

On this day in 1913 the Women's Pilgrimage begins. In 1913 the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) had nearly had 100,000 members. Katherine Harley, a senior figure in the NUWSS, suggested holding a "Woman's Suffrage Pilgrimage" in order to show Parliament how many women wanted the vote. According to Lisa Tickner, the author of The Spectacle of Women (1987) argued: "A pilgrimage refused the thrill attendant on women's militancy, no matter how strongly the militancy was denounced, but it also refused the glamour of an orchestrated spectacle."

Members of the NUWSS set off on 18th June, 1913. The North-Eastern Federation, the North and East Ridings Federation, the West Riding Federation, the East Midland Federation and the Eastern Counties Federation, travelled the Newcastle-upon-Tyne to London route. The North-Western Federation, the Manchester and District, the West Lancashire, West Cheshire and North Wales Federation, the West Midlands Federation, and the Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire Federation travelled on the Carlisle to the capital route. The South-Western Federation, the West of England Federation, the Surrey, Sussex and Hampshire Federation walked from Lands End to Hyde Park.

As Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), pointed out: "Pilgrims were urged to wear a uniform, a concept always close to Katherine Harley's heart. It was suggested that pilgrims should wear white, grey, black, or navy blue coats and skirts or dresses. Blouses were either to match the skirt or to be white. Hats were to be simple, and only black, white, grey, or navy blue. For 3d, headquarters supplied a compulsory raffia badge, a cockle shell, the traditional symbol of pilgrimage, to be worn pinned to the hat. Also available were a red, white and green shoulder sash, a haversack, made of bright red waterproof cloth edged with green with white lettering spelling out the route travelled, and umbrellas in green or white, or red cotton covers to co-ordinate civilian umbrellas."

Members of the NUWSS publicized the Women's Pilgrimage in local newspapers. Helen Hoare, for example, sent a letter to The East Grinstead Observer: "It is no doubt true that some men were formerly inclined to support it have been alienated by the doings of the militant party. The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society (that is the law-abiding, non-militant party), in order to show the world that it is alive, and to encourage its members in a long and disheartening struggle, has organised a great pilgrimage from all parts of England to London."

Lisa Tickner has pointed out: "Most women travelled on foot, though some rode horses or bicycles, and wealthy sympathisers lent cars, carriages, or pony traps for the luggage. The intention was not that each individual should cover the whole route but that the federations would do so collectively." One of the marchers, Margory Lees, claimed that the pilgrimage succeeded in "visiting the people of this country in their own homes and villages, to explain to them the real meaning of the movement." Another participant, Margaret Greg, recorded: "My verdict on the Pilgrimage is that it is going to do a very great deal of work - the sort of work that has hitherto only been done by towns or at election times is being spread all over the country." The pilgrims were accompanied by a lorry, containing their baggage. Margaret Ashton brought her car and picked up those suffering from exhaustion.

During the next six weeks held a series of meetings all over Britain where they sold The Common Cause and other NUWSS literature. The meetings held on the way were nearly all peaceful. However, the women had to endure a great deal of abuse. Harriet Blessley of Portsmouth recalled: "It is difficult to feel a holy pilgrim when one is called a brazen hussy."

A serious riot took place at a meeting organised by Marie Corbett of the East Grinstead Suffrage Society and Edward Steer of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage at East Grinstead three days before the end of the march. As the The East Grinstead Observer reported: "The procession was not an imposing one. It consisted of about ten ladies who were members of the Suffrage Society. Mrs. Marie Corbett led the way carrying a silken banner bearing the arms of East Grinstead. The reception, which the little band of ladies got, was no means friendly. Yells and hooting greeted them throughout most of the entire march, and they were the targets for occasional pieces of turf, especially when they passed through Queen’s Road. In the High Street they found a crowd of about 1,500 people awaiting them."

Edward Steer was the chairman and Laurence Housman was the main speaker. The local newspaper reported that both men were attacked by the crowd: "By this time pieces of turf and a few ripe tomatoes and highly seasoned eggs were flying about, and were not always received by the person they were intended for. The unsavoury odur of eggs was noticeable over a considerable area. Unhappily, Miss Helen Hoare of Charlwood Farm, was struck in the face with a missile and received a cut on the cheek and was taken away for treatment."

Despite this riot The Common Cause reported that overall the pilgrimage was a great success and "the result was nothing less than a revelation, to those who doubted it, of the almost universal sympathy given to the Non-militant Suffrage Cause once it is understood." The Daily News commented on the woman's brown skins on the march and added "never was so peaceful, so pleasant a raid of London - and rarely one more picturesque or more inspiring."

An estimated 50,000 women reached Hyde Park in London on 26th July. As The Times newspaper pointed out, the march was part of a campaign against the violent methods being used by the Women Social & Political Union: "On Saturday the pilgrimage of the law abiding advocates of votes for women ended in a great gathering in Hyde Park attended by some 50,000 persons. The proceedings were quite orderly and devoid of any untoward incident. The proceedings, indeed, were as much a demonstration against militancy as one in favour of women's suffrage. Many bitter things were said of the militant women."

On 29th July 1913, Millicent Fawcett wrote to Herbert Asquith "on behalf of the immense meetings which assembled in Hyde Park on Saturday and voted with practical unanimity in favour of a Government measure." Asquith replied that the demonstration had "a special claim" on his consideration and stood "upon another footing from similar demands proceeding from other quarters where a different method and spirit is predominant."

On this day in 1913 The Scotsman newspaper writes about the WSPU conspiracy trial. On 30th April 1913 the police raided the WSPU's office at Lincoln's Inn House. As a result of the documents found several people were arrested including Edwy Godwin Clayton, Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney, Rachel Barrett (editor of the The Suffragette), Harriet Kerr (office manager), Beatrice Sanders (financial secretary), Geraldine Lennox (sub-editor) and Agnes Lake (business manager).

When he was arrested Clayton said: "I think this is rather a high-handed action. I am an extreme sympathizer with the Suffragette causes. What evidence have you against me?" He confirmed he had written the letter but refused to comment on the contents. The letter read: "Dear Miss Kenney, I am sorry to say it will be several days yet before I can be ready with which you want. I have devoted all this evening and all of yesterday evening to the business without success. Evidently it is a difficult matter, but not impossible. I nearly succeeded once last night and then spoilt what I had done in trying to improve upon it. By next week I shall be able to manage the exact proportions, and I will let you have the results as soon as I can. Please burn this."

During the trial Matthias McDonnell Bodkin read extracts from a document headed "Votes for Women" and underneath "YHB". Bodkin claimed that YHB stood for Young Hot Bloods. The label was derived from a taunt thrown at Emmeline Pankhurst in one of the newspapers, which ran: "Mrs Pankhurst will, of course, be followed blindly by a number of the younger and more hot-blooded members of the union". As a result of them being single women one newspaper described the Young Hot Bloods as "a spinsters' secret sect".

Bodkin claimed that the police seized a great number of documents, that showed according to Bodkin that Clayton "put his knowledge and his brain at the Union's disposal for the purpose of carrying out crimes and of producing the reign of terror in London." Receipts for money he had been paid by the union were produced in court.

The most incriminating evidence was a letter sent by Clayton to Jessie Kenney in April 1913 that was found inside a book on the 1831 Bristol Reform Riots. Bodkin said: "We did not know until these documents were seized at their offices that they had an analytical chemist in their service – a man who, as we know, written a secret letter which the vain folly of Miss Kenney causes her to leave in her bedroom. the letter he tells her he had been experimenting, and was on the brink of success. Clayton ended his letter: "Burn this letter."

Bodkin provided other documents written by Clayton. One document in Clayton's writing was headed "Various Suggestions" and read "Scheme of simultaneously smashing a considerable number of street fire-alarms. This will cause tremendous confusion and excitement and should be as especially a good idea. It should be at once easier and less risky to execute than some other operations". Particulars as to timber yards and cotton mills also followed, as well as a plan for burning down the National Health Insurance Office.

Another witness Mrs Strange, the proprietress of the refreshment pavilion at Kew Gardens, estimated the amount of damage done to the pavilion by the fire which took place there some time ago. Lilian Lenton and Olive Wharry were arrested and when they appeared at Richmond Police Court, she saw Clayton with them.

In his summing up Justice Walter Phillimore, remarked that it was one of the saddest trials in his experience of nearly sixteen years as a Judge. "How in morals and how in good practical sense could such things, if they be true be justified? It was said that great causes had never been won without breaking the law. That might be true of some cases; it was very untrue of others. If every recorded act of anarchy, then, as history proceeded on its long course, the human race would reach a position of absolute savagery, and the only chance of salvation would be the obliteration of memory."

During the trial, Rachel Barrett said: "When we hear of a bomb being thrown we say 'Thank God for that'. If we have any qualms of conscience, it is not because of things that happen, but because of things that have been left undone." Barrett was sentenced to six months in prison. She was described by one of the prosecuting barristers at the trial as "a pretty but misguided young woman".

After an absence of an hour the jury found all the prisoners guilty, with strong recommendations for leniency of sentence in the case of the three younger women, Rachel Barrett, Geraldine Lennox and Agnes Lake. The Judge said: "I agree with you, gentlemen of the jury, in the discrimination which you have made between the younger and elder men and women… which I propose to show in their sentences: As I have said, I assume you have been animated through out by the best motives. It is not merely that some of you have committed organized outrages, but I am more concerned with the incitement that has been given to young and irresponsible women, whose actions are not always balanced by their reason to do things which you are sure to regret."

Annie Kenney was sentenced to eighteen months but it was Edwy Godwin Clayton who was treated most harshly and got twenty-one months. He went on hunger strike and was released on license, however, he went on the run and managed to evade arrest and went to live in Europe.

Clayton wrote a letter that was published in Votes for Women. "We have received a letter, without address but bearing a foreign postmark from Mr Edwy Clayton, who it will be remembered was sentenced to twenty-one months' imprisonment last year in connection with the Conspiracy Trial of the WSPU officials, and was afterwards released on license under the Cat and Mouse Act and has not been re-arrested. He writes to say with reference to the House Secretary's recent allusions to 'paid' militant Suffragists, that the similar implications of the prosecution, in his own case at his own trial last year, while utterly unfounded." He added: "I neither received nor desired to receive payment for any assistance given by me to the women's movement. My sole reward has been the happiness derived from personal participation, as a volunteer helper, in this campaign against prejudice, ignorance, disease, and brutality."

Sylvia Pankhurst pointed out that the court case had a disastrous impact on his professional career: "He (Clayton) had been purely a voluntary worker for the Union, happy, as he wrote, to give his services to a cause he believed just. His business ruined, he was reduced to great poverty, and was eventually assisted by J. E. Francis of the Athenaeum Press, who paid him a small wage".

On this day in 1915 Olive Schreiner writes letter to Adela Smith about the First World War. "It is the thought of all these beautiful young lives cut down before they have even tasted of the cup of life that wrings my heart so. I have never met a human creature who hates war as I hate it. I can only fix my eyes on that far off time over thousands of years, when humanity will realise that all men are brothers; that it is finer to bring one noble human being into the world and rear it well for the broadest human ends, than to kill ten thousand. It's because of men like Paul Methuen and my nephew Oliver do and might mean so much to the world that I feel the risk of losing them so much, and I can't bear to think they're killing anyone."

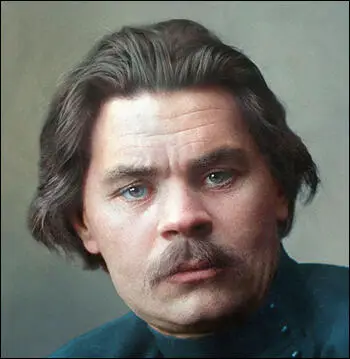

On this day in 1936 Maxim Gorky died of a heart attack on 18th June, 1936. Rumours began circulating that Stalin had arranged for him to be murdered. This story was given some support when Genrikh Yagoda, the head of the NKVD at the time of his death, was successfully convicted of Gorky's murder in 1938.

Alexander Peshkov (later known as Maxim Gorky was born in Nizhny Novgorod on 28th March, 1868. His father was a shipping agent but he died when Gorky was only five years old. His mother remarried and Gorky was brought up by his grandmother.

Gorky left home in 1879 and went to live in a small village in Kazan and worked as a baker. At this time radical groups such as the Land and Liberty group sent people into rural areas to educate the peasants. Gorky attended these meetings and it was during this period that Gorky read the works of Nikolai Chernyshevsky, Peter Lavrov , Alexander Herzen, Karl Marx and George Plekhanov. Gorky became a Marxist but he was later to say that was largely because of the teachings of the village baker, Vasilii Semenov.

In 1887 Gorky witnessed a Pogrom in Nizhny Novgorod. Deeply shocked by what he saw, Gorky became a life-long opponent of racism. Gorky worked with the Liberation of Labour group and in October, 1889 was arrested and accused of spreading revolutionary propaganda. He was later released because they did not have enough evidence to gain a conviction. However, the Okhrana decided to keep him under police surveillance.

Osip Volzhanin met Gorky in 1889: "He was tall, stooped, dressed in a coat-like jacket and high polished boots. His face was ordinary, plebeian, with a homely duck-like nose. By his appearance he could easily have been taken for a worker or a craftsman. The young man sat on the window sill, and swinging his long legs, spoke strongly emphasizing the letter 'O'. We listened with great delight to his stories, though Somov, an implacable 'political', disapproved of the stories and the behaviour of the young man. In his opinion, the latter occupied himself with trifles."

In 1891 Gorky moved to Tiflis where he found employment as a painter in a railway yard. The following year his first short-story, Makar Chudra, appeared in the Tiflis newspaper, Kavkaz. He story appeared under the name Maxim Gorky (Maxim the Bitter). The story was popular with the readers and soon others began appearing in other journals such as the successful Russian Wealth.

Gorky also began writing articles on politics and literature for newspapers. In 1895 he began writing a daily column under the heading, By the Way. In this articles he campaigned against the eviction of peasants from their land and the persecution of trade unionists in Russia. He also criticized the country's poor educational standards, the government's treatment of the Jewish community and the growth in foreign investment in Russia.

In his story Twenty-six Men and a Girl, one of his characters comment: “The poor are always rich in children, and in the dirt and ditches of this street there are groups of them from morning to night, hungry, naked and dirty. Children are the living flowers of the earth, but these had the appearance of flowers that have faded prematurely, because they grew in ground where there was no healthy nourishment.”

Gorky's short stories often showed Gorky's interest in social reform. In a letter to a friend, Gorky argued that "the aim of literature is to help man to understand himself, to strengthen the trust in himself, and to develop in him the striving toward truth; it is to fight meanness in people, to learn how to find the good in them, to awake in their souls shame, anger, courage; to do all in order that man should become nobly strong."

In 1898 Gorky published his first collection of short-stories. The book was a great success and he was now one of the country's most read and discussed writers. His choice of heroes and themes helped him emerge as the champion of the poor and the oppressed. The Okhrana became greatly concerned with Gorky's outspoken views, especially his articles and stories about the police, but his increasing popularity with the public made it difficult for them to take action against him.

Gorky secretly began helping illegal organizations such as the Socialist Revolutionaries and the Social Democratic Labour Party. He donated money to party funds and helped with the distribution of radical newspapers such as Iskra. One Bolsheviks later recalled that Gorky's contribution included "financial help systematically paid every month, technical assistance in the establishment of printing shops, organizing transport of illegal literature, arranging for meeting places, and supplying addresses of people who could be helpful."

On 4th March, 1901, Gorky witnessed a police attack on a student demonstration in Kazan. After publishing a statement attacking the way the police treated the demonstrators, Gorky was arrested and imprisoned. Gorky's health deteriorated and afraid he would die, the authorities released him after a month. He was put under house arrest, his correspondence was monitored and restrictions were placed on his movement around the country. When he was allowed to travel to the Crimea, he was greeted on the route by large crowds bearing banners with the words: "Long live Gorky, the bard of Freedom exiled without investigation or trial."

In 1902 Gorky was elected to the Imperial Academy of Literature. Nicholas II was furious when he heard the news and wrote to his Minister of Education: "Neither Gorky's age nor his works provide enough ground to warrant his election to such an honorary title. Much more serious is the circumstance that he is under police surveillance. And the Academy is allowing, in our troubled times, such a person to be elected! I am deeply dismayed by all this and entrust to you to announce that on my orders, the election of Gorky is to be cancelled."

When news that the Academy had followed the Tsar's orders and had overruled Gorky's election, several writers resigned in protest. Later that year the statutes of the Academy were changed, giving Nicholas II the power to approve the list of candidates before they came up for election.

Maxim Gorky gave his support to Father George Gapon and his planned march to the Winter Palace. He attended the march on the 22nd January, 1905, and that night Gapon stayed in his house. After Blood Sunday Gorky changed his mind about the moral right for revolutionaries to use violence. He wrote to a friend: "Two hundred black eyes will not paint Russian history over in a brighter colour; for that, blood is needed, much blood. Life has been built on cruelty and force. For its reconstruction, it demands cold calculated cruelty - that is all! They kill? It is necessary to do so! Otherwise what will you do? Will you go to Count Tolstoy and wait with him?"

After Blood Sunday Gorky was arrested and charged with inciting the people to revolt. Following a wide-world protest at Gorky's imprisonment in the Peter and Paul Fortress, Nicholas II agreed for him to be deported from Russia. Gorky now spent his time attempting to gain support for the overthrow of the Russian autocracy. This included raising money to buy arms for the Socialist Revolutionaries and the Social Democratic Labour Party. He also helped to fund the new Bolsheviks newspaper Novaya Zhizn.

In 1906 Gorky toured Europe and the United States. He arrived in New York on 28th March, 1906 and the New York Times reported that "the reception given to Gorky revealed with that of Kossuth and Garibaldi." His campaign tour was organized by a group of writers that included Ernest Poole, William Dean Howells, Jack London, Mark Twain, Charles Beard and Upton Sinclair.

The New York World newspaper decided to run a smear campaign against Gorky. The American public were shocked to hear that Gorky was staying in his hotel with a woman who was not his wife. The newspaper printed that the "so-called Mme Gorky who is not Mme Gorky at all, but a Russian actress Andreeva, with whom he has been living since his separation from his wife a few years ago." As a result of the story Gorky was evicted from his hotel and William Dean Howells and Mark Twain changed their mind about supporting his campaign. President Theodore Roosevelt also withdrew his invitation for Gorky to meet him in the White House.

Others such as H. G. Wells continued to help Gorky and issued a statement that included the comment: "I do not know what motive actuated a certain section of the American press to initiate the pelting of Maxim Gorky. A passion for moral purity ever before begot so brazen and abundant torrent of lies." Frank Giddings, a sociologist, compared the attack on Gorky to the lynching of three African Americans in Missouri. "Maxim Gorky came to this country not for the purpose of putting himself on exhibition, as many literary characters have done at one time or another, not for the purpose of lining his pockets with American gold, but for the purpose of obtaining sympathy and financial assistance for a people struggling against terrific odds, as the American people once struggled, for political and individual liberty. All was assertion, accusation, hysteria, impertinence in the way the papers have tried to instruct Gorky in morality."

Gorky also upset other supporters by sending a telegram of support to William Haywood, the leader of the Industrial Workers of the World, who was in prison waiting to be tried for the murder of the politician, Frank Steunenberg. Later Gorky published a book American Sketches, where he criticized the gross inequalities in American society. In one article he wrote that if anyone "wanted to become a socialist in a hurry, he should come to the United States."

In 1907 Gorky attended the Fifth Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party. While there he met Lenin, Julius Martov, George Plekhanov, Leon Trotsky and other leaders of the party. Gorky preferred Martov and the Mensheviks and was highly critical of Lenin's attempts to create a small party of professional revolutionaries. Gorky commented that he was not impressed with Lenin: "I did not expect Lenin to be like that. Something was lacking in him. He rolled his r's gutturally, and had a jaunty way of standing with his hands somehow poked up under his armpits. He was somehow too ordinary and did not give the impression of being a leader."

Gorky was later to write about Lenin: "Squat and solid, with a skull like Socrates and the all-seeing eyes of a great deceiver, he often liked to assume a strange and somewhat ludicrous posture: throw his head backwards, then incline it to the shoulder, put his hands under his armpits, behind the vest. There was in this posture something delightfully comical, something triumphantly cocky. At such moments his whole being radiated happiness. His movements were lithe and supple and his sparing but forceful gestures harmonized well with his words, also sparing but abounding in significance. From his face of Mongolian cast gleamed and flashed the eyes of a tireless hunter of falsehood and of the woes of life - eyes that squinted, blinked, sparkled sardonically, or glowered with rage. The glare of those eyes rendered his words more burning and more poignantly clear.... A passion for gambling was part of Lenin's character. But this was not the gambling of a self-centred fortune seeker. In Lenin it expressed that extraordinary power of faith which is found in a man firmly believing in his calling, one who is deeply and fully conscious of his bond with the world outside and has thoroughly understood his role in the chaos of the world, the role of an enemy of chaos."

Gorky continued to write and his most successful novels include Three of Them (1900), Mother (1906), A Confession (1908), Okurov City (1909) and the Life of Matvey Kozhemyakin (1910). Gorky argued: "The aim of literature is to help man to understand himself, to strengthen the trust in himself, and to develop in him the striving toward truth; it is to fight meanness in people, to learn how to find the good in them, to awake in their souls shame, anger, courage; to do all in order that man should become nobly strong."

Gorky was strongly opposed the First World War and he was attacked in the Russian press as being unpatriotic. In 1915 he established the political-literary journal, Letopis (Chronicle) and helped establish the Russian Society of the Life of the Jews, an organization that protested against the persecution of the Jewish community in Russia.

In March, 1917, Gorky welcomed the abdication of Nicholas II and supported the Provisional Government. Gorky wrote to his son: "We won not because we are strong, but because the government was weak. We have made a political revolution and have to reinforce our conquest. I am a social democrat, but I am saying and will continue to say, that the time has not come for socialist-style reforms."

With the support of the Mensheviks, Gorky started a newspaper, New Life, in 1917, and used it to attack the idea that the Bolsheviks were planning to overthrow the government of Alexander Kerensky. On 16th October, 1917, he called on Lenin to deny these rumours and show he was "capable of leading the masses, and not a weapon in the hands of shameless adventurers of fanatics gone mad."

After the October Revolution the new government got Joseph Stalin to lead the attack on Gorky. In the newspaper Workers' Road, Stalin wrote: "A whole list of such great names was discarded by the Russian Revolution. Plekhanov, Kropotkin, Breshkovskaia, Zasulich and all those revolutionaries who are distinguished only because they are old. We fear that Gorky is drawn towards them, into the archives. Well, to each his own. The Revolution neither pities nor buries its dead."

Gorky retaliated by writing in the New Life in 7th November, 1917. "Lenin and Trotsky and their followers already have been poisoned by the rotten venom of power. The proof of this is their attitude toward freedom of speech and of person and toward all the ideals for which democracy was fighting." Three days later Gorky called Lenin and Leon Trotsky the "Napoleons of socialism" who were involved in a "cruel experiment with the Russian people."

Victor Serge met Gorky during this period: "His apartment at the Kronversky Prospect, full of books, seemed as warm as a greenhouse. He himself was chilly even under his thick grey sweater, and coughed terribly, the result of his thirty years' struggle against tuberculosis. Tall, lean and bony, broad-shouldered and hollow-chested, he stooped a little as he walked. His frame, sturdily-built but anaemic, appeared essentially as a support for his head. An ordinary, Russian man in the street's head, bony and pitted, really almost ugly with its jutting cheek-bones, great thin-lipped mouth and professional smeller's nose, broad and peaked."

In January, 1918, Gorky led the attack on Lenin's decision to close down the Constituent Assembly. Gorky wrote in the New Life that the Bolsheviks had betrayed the ideals of generations of reformers: "For a hundred years the best people of Russia lived with the hope of a Constituent Assembly. In this struggle for this idea thousands of the intelligentsia perished along with tens of thousands of workers and peasants."

The Bolshevik government controlled the distribution of newsprint and in July, 1918, it cut off supplies to New Life and Gorky was forced to close his newspaper. The government also took action making it impossible for Gorky to get his work published in Russia.

During the Civil War Gorky agreed to give his support to the Bolsheviks against the White Army. In return Lenin gave him permission to establish the publishing company, World Literature. This enabled Gorky to give employment to people such as Victor Serge and other critics of the Soviet government. Privately, Gorky remained an opponent of the government. In September, 1919, he wrote to Lenin: "for me it became clear that the "reds" are the enemies of the people just as the "whites". Personally, I of course would rather be destroyed by the "whites", but the "reds" are also no comrades of mine."