On this day on 14th January

On this day in 1862 George Julian makes important speech in the Senate on slavery. Julian was elected to the 37th Congress in 1860 and along with his father-in-law, Joshua Giddings, became a leading figure in the group that became known as the Radical Republicans.

"This rebellion is a bloody and frightful demonstration of the fact that slavery and freedom cannot dwell together in peace. Why is it, that in the great centres of slavery treason is rampant, while, as we recede into regions in which the slaves are few and scattered, as in Western Virginia, Delaware, and other border States, we find the people loyally disposed toward the Union? I know it was not the purpose of this administration, at first, to abolish slavery, but only to save the Union, and maintain the old order of things. Neither was it the purpose of our fathers, in the beginning of the Revolution, to insist on independence. The policy of emancipation has been born of the circumstances of the rebellion, which every hour more and more plead for it. I believe the popular demand now is, or soon will be, the total extirpation of slavery as the righteous purpose of the war, and the only means of a lasting peace."

During the American Civil War Julian argued that the Union Army should not only free the slaves but to reconstruct Southern society. Julian strongly supported the Freeman's Bureau, the Civil Rights Bill and the Reconstruction Acts. After the war Julian clashed with President Andrew Johnson and voted for his impeachment in 1868.

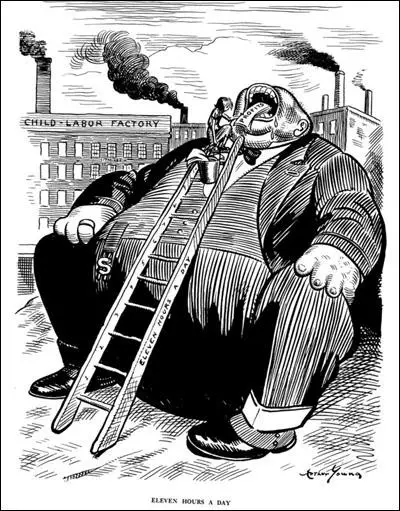

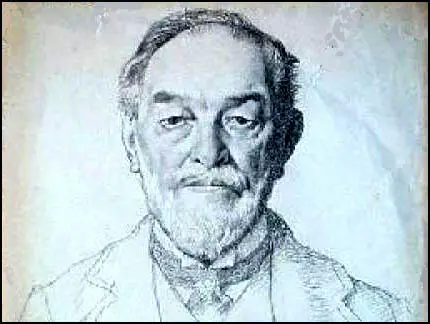

On this day in 1866 Art Young was born in Stephenson County, Illinois. His family moved to Monroe, Wisconsin, when he was a child to run a general store and a twenty-acre farm. When he was a boy Young borrowed a book from the local library that had been illustrated by Gustave Dore. Young was so impressed with these drawings that he decided to become an illustrator.

Young sent his drawings to journals in Chicago and at the age of seventeen had his first work accepted by the Judge Magazine. Soon after the publication of his first drawing, Young moved to the city where he studied at its Academy of Design. He paid for the course by illustrating news stories in the Chicago Evening Mail. Young soon developed a reputation as a talented artist and was offered work with the Chicago Daily News and the Chicago Inter-Ocean. In 1885 he married Elizabeth North and three years later they moved to New York City and Young became a student at the Arts Students League.

Young also had his cartoons published in Life and Puck and provided drawings to illustrate news stories for the Evening Journal. One of these assignments included a speech given by Keir Hardie, the British trade union leader and the first socialist member of the House of Commons. Later, Young recalled how listening to Hardie encouraged him to start questioning his previously held, conservative views.

In March 1902 Young was commissioned to draw an anti-immigration picture for Life. After it was published he sent back the $100 cheque and vowed that in future he would only draw pictures that reflected his own political beliefs. By this time Young's work was so highly valued that newspapers and magazines were willing to accept his drawings attacking inequality and supporting causes he believed in such as women's rights.

When Piet Vlag decided to start a new socialist magazine, The Masses, in 1910, he asked Young to join him. Other early members of the team included Louis Untermeyer and John Sloan. Organised like a co-operative, artists and writers who contributed to the journal shared in its management. According to Barbara Gelb: "After about a year and a half the Masses floundered and its tiny staff of contributors, which included the artist, John Sloan, the cartoonist, Art Young, and the poet, Louis Untermeyer, held an emergency session to rescue it. It was Young's idea to ask Max Eastman, a twenty-nine-year-old Columbia professor who had recently been dismissed for his radical views, to take over the editorship of the Masses."

In 1912 Max Eastman, a Marxist, agreed to become editor of the journal. In his first editorial, Eastman argued: "This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine: a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable: frank, arrogant, impertinent, searching for true causes: a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found: printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press: a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers."

Art Young later recalled: "I think we have the true religion. If only the crusade would take on more converts. But faith, like the faith they talk about in the churches, is ours and the goal is not unlike theirs, in that we want the same objectives but want it here on earth and not in the sky when we die."

Over the next few years The Masses published articles and poems written by people such as John Reed, Sherwood Anderson, Crystal Eastman, Hubert Harrison, Inez Milholland, Mary Heaton Vorse, Louis Untermeyer, Randolf Bourne, Dorothy Day, Helen Keller, William Walling, Carl Sandburg, Upton Sinclair, Amy Lowell, Mabel Dodge, Floyd Dell and Louise Bryant.

The Masses also published the work of important artists including John Sloan, Robert Henri, Alice Beach Winter, Mary Ellen Sigsbee, Cornelia Barns, Reginald Marsh, Rockwell Kent, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, Lydia Gibson, K. R. Chamberlain, Stuart Davis, George Bellows and Maurice Becker.

In 1913 Art Young and Max Eastman were charged with criminal libel after the publication of a cartoon, Poisoned at the Source. Floyd Dell later explained what happened: "The Masses decided to look into the case (a strike in West Virginia). It decided that if this thing were true, it ought to be stated without delicacy. The result was a paragraph warmly charging the Associated Press with having suppressed and colored the news of the strike in favour of the employers. Accompanying the paragraph was a cartoon presenting the same charge in a graphic form. Upon the basis of this cartoon and paragraph, William Rand, an attorney for the Associated Press, brought John Doe proceedings against the Masses." After the case was dismissed in the Municipal Court of New York City, Rand successfully approached the District Attorney and both men were arrested. Associated Press eventually dropped the case. However, after a year, the company decided to drop the law suit.

William L. O'Neill, the author of Echoes of Revolt: The Masses 1911-1917 (1966) has pointed out: "Art Young had that singular contempt for the pretensions of the press which only long and intimate associations produces. As a professional cartoonist he knew whereof he drew, and the scorn he lavished on the Associated Press was only part, as this drawing indicated, of the utter distaste he felt for the brothel economics of the industry as a whole."

At The Masses Young sometimes clashed with its art editor, John Sloan. Young believed that Sloan was more interested in art than socialism. When Sloan left in 1916 after a dispute with the more politically committed members of the co-operative, Young commented: "To me this magazine exists for socialism. That's why I give my drawings to it, anybody who doesn't believe in a socialist policy, as far as I go, can get out."

Although Young was his cartoons always had a political objective, they were often difficult to interpret. The dominant theme in his cartoons was to attack hypocrisy and show the real truth behind the official image. One cartoon for example, Respectability, published in August 1915, shows a well-dressed man, closing some curtains in his house. The critic, Richard Fitzgerald, in his book, Art and Politics (1973), argues that the man "who could be a railroad magnate, a pillar of society, is shown in a private moment of desperate anxiety and fear symbolically concealing objects that no doubt represent the various deviant tendencies behind the facade of respectability."

Young, like most of the people working for The Masses, believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and that the USA should remain neutral. This was reflected in Young's cartoons that attacked the behaviour of both sides in the conflict.

After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, The Masses came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges. In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and H. J. Glintenkamp and articles by Max Eastman and Floyd Dell had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort.

Floyd Dell argued in court: "There are some laws that the individual feels he cannot obey, and he will suffer any punishment, even that of death, rather than recognize them as having authority over him. This fundamental stubbornness of the free soul, against which all the powers of the state are helpless, constitutes a conscious objection, whatever its sources may be in political or social opinion." The legal action that followed forced The Masses to cease publication. In April, 1918, after three days of deliberation, the jury failed to agree on the guilt of the defendants.

The second trial was held in January 1919. John Reed, who had recently returned from Russia, was also arrested and charged with the original defendants. Floyd Dell wrote in his autobiography, Homecoming (1933): "While we waited, I began to ponder for myself the question which the jury had retired to decide. Were we innocent or guilty? We certainly hadn't conspired to do anything. But what had we tried to do? Defiantly tell the truth. For what purpose? To keep some truth alive in a world full of lies. And what was the good of that? I don't know. But I was glad I had taken part in that act of defiant truth-telling." This time eight of the twelve jurors voted for acquittal. As the First World War was now over, it was decided not to take them to court for a third time.

Over the next few years Young had cartoons published in two radical journals he had helped to establish, The Liberator (1918-24) and Good Morning (1919-21). He also provided material for the Saturday Evening Post, The Nation, New Masses, Appeal to Reason, The Call, and the New Leader.

In 1934 Young was in poor health and close and close to bankruptcy and so a group of friends organised a testimonial benefit in New York City. Young was too ill to attend but he sent a message to the event. "I'm a little worse for wear. But I will try to express myself hereafter with bigger and better bitterness. I don't know the meaning of dialectical materialism. All I know is that the cause of the workers is right and the rule of capitalism is wrong, and right will win."

Art Young published two autobiographies, On My Way (1928) and Art Young: His Life and Times (1939) and a book of his cartoons, The Best of Art Young (1936). Art Young continued to produce politically committed cartoons until his death on 29th December 1943.

On this day in 1885 Rudolf Olden, the son of the author, Hans Olden, was born in Stettin on 14th January, 1885. His brother, Balder Olden, later wrote: "At the age of fifteen he was the complete gentleman. No speck of dust was to be found on his always perfectly pressed suit, his immaculate manners could become decidely frosty, he was slim, tall, aristocratic in every gesture."

After completing his education he joined German Army in Darmstadt. During the First World War he served on both the Western Front and the Eastern Front. He was wounded twice and by the end of the war he reached the rank of First Lieutenant.

Sickened by the slaughter of the war he became a pacifist and moved to Vienna where he edited the anti-war periodical Der Friede (Peace). In 1920 he married the psychoanalyst Marie-Christine Fournier, the daughter of the historian August Fournier. After working as a journalist for Der Neue Tag, he founded a magazine Er und Sie (He and She). Volkmar Zühlsdorff has argued: "Rudolf Olden was an impressive personality - one of the 200 figures who really counted for something in Berlin, as Kurt Tucholsky once observed. For all his sympathetic, selfless readiness to stick up for other people, he was also capable of ruthless attacks and cutting judgements when he considered them appropriate." It was claimed that whenever somebody said something foolish he had the habit of inserting his monocle and fixing his gaze on his opponent and would say two words: "You reckon?"

In 1926 Olden moved to Berlin where he was employed by Theodor Wolff, the owner of the liberal Berliner Tageblatt newspaper, as political editor. Wolff was Jewish and the newspaper became a forum for those willing to criticize the policies of the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). Olden was also a member of the managing board of the German League for Human Rights.

Rudolf Olden also worked as a lawyer and successfully defended Carl von Ossietzky, the editor of Die Weltbühne, after it had published evidence that Germany was in violation of its agreements under the Treaty of Versailles. As Volkmar Zühlsdorff, the author of Hitler's Exiles (2005), has pointed out: "Olden built up a reputation throughout Germany and even abroad as defence counsel. He favoured cases which offended his pronounced sense of justice and humanity, irrespective of the status of those involved, the party they belonged to or to the political repercussions."

In January 1933 Adolf Hitler obtained power in Germany. Olden immediately helped to organize a congress Das Freie Wort, where over 1,500 artists, authors, scientists and politicians pledge their support for artistic, journalistic and academic freedoms. Warned that he was about to be arrested, Olden fled to Prague, where he continued his campaign against fascism. In 1934 he was invited by Gilbert Murray to move to London where he gave lectures on Nazi Germany and became secretary of PEN International.

In 1936 Olden published Hitler the Pawn. The book rejected the idea that Hitler won power through his own efforts. He took the view that he was presented with the opportunity by powerful figures such as Paul von Hindenburg and Franz von Papen. The book included interviews with people such as Reinhold Hanisch who knew Hitler in Vienna before the First World War. On the publication of the book Olden's German citizenship was revoked. In 1939, at the outbreak of war, Olden was interned. He was released when he was invited to lecture at the New School of Social Research in New York City.

On boarding the City of Benares, his passport was stamped with the words "No Return". It was carrying 406 passengers and crew, of whom 100 were children being evacuated to Canada and the US, most of them as part of a government scheme organized by the Children's Overseas Reception Board. On 18th September 1940, the ship was torpedoed by the German submarine U-48. As a result 258 people died, including Rudolf Olden and his wife Marie-Christine Olden. Nazi German propaganda later claimed Olden was on a mission to persuade the then-neutral United States to enter the war.

On this day in 1892 Martin Niemöller, the son of a pastor, was born in Lippstadt, Germany. At the age of eighteen Niemöller became an officer-cadet in the German Navy. Niemöller was assigned to the training vessel Hertha and eventually graduated to the battleship Thuringen.

By the time the First World War began in 1914, Niemöller had reached the rank of Sub-Lieutenant. It was decided that the Thuringen was too old and was retired from active service. Niemöller was now assigned to a mine-laying submarine (U73). This was followed by spells as an officer on the U39 and the U151. In 1918 Niemöller took command of the UC67. Later that year he was responsible for laying mines off Marseilles. This operation resulted in sinking three enemy ships totalling 17,000 tons. By the end of the war Niemöller was seen as one of Germany's most successful U-boat captains and was awarded the Iron Cross (first class).

After the war Niemöller became active in German politics. Senior officers in the German Army began raising private armies called Freikorps. These were used to defend the German borders against the possibility of invasion from the Red Army. Niemöller joined this group and took part in the attempt to stop a socialist revolution taking place in Germany.

In March, 1919, General Franz Epp led 30,000 soldiers to crush the Bavarian Socialist Republic. It is estimated that Epp's men killed over 600 communists and socialists over the next few weeks. The following year Herman Ehrhardt, a former naval commander and Wolfgang Kapp, a right-wing journalist, led a group of soldiers to take control of Berlin. Niemöller supported this Kapp Putsch and commanded a battalion of Freikorps in Munster. The right-wing coup was eventually defeated by a general strike of trade unionists.

After the establishment of the Weimar Republic Niemöller decided to study theology. He remained interested in politics and became a supporter Adolf Hitler and in the 1924 elections voted for the Nazi Party. Even after he was ordained in 1929 and became pastor of the Church of Jesus Christ at Dahlem he remained an ardent supporter of Hitler. In 1931 Niemöller made speeches where he argued that Germany needed a Führer.

In his sermons he also espoused Hitler's views on race and nationality. In 1933 he described the programme of the Nazi Party as a "renewal movement based on a Christian moral foundation". The following year Niemöller published his autobiography From U-Boat to Pulpit. This right-wing nationalist view of the war and its aftermath made it a popular book with party members and sold 90,000 copies in the first few weeks after it was published.

In 1933 Niemöller complained about the decision by Adolf Hitler to appoint Ludwig Muller, as the country's Reich Bishop of the Protestant Church. With the support of Karl Barth, a professor of theology at Bonn University, in May, 1934, a group of rebel pastors formed what became known as the Confessional Church.

When the Nazi government continued with this policy Niemöller joined with Dietrich Bonhoffer to form the Pastors' Emergency League and published a major document opposing the religious policies of Adolf Hitler. Niemöller was particularly concerned by Hitler's decision that Jews should be expelled from the Church. He argued that once Jews had been converted to Christianity they should be allowed to remain in the Church. As Bonhoffer pointed out at the time, although Niemöller was critical of Hitler he remained a committed supporter of the Nazi Party. Niemöller was later to admit that his group "acted as if we had only to sustain the church" and did not accept that they had a "responsibility for the whole nation".

Niemöller therefore did not criticize the Nazi Party for putting its political opponents into concentration camps. However, he spoke out when members of the Protestant Church were arrested. In his sermon on Sunday 27th June 1937, Niemöller pointed out that on: "On Wednesday the secret police penetrated the closed church of Friedrich Werder and arrested at the altar eight members of the Council of Brethren."

The following month Niemöller was himself arrested. He was held eight months without trial and when his case eventually took place he was found guilty of "abusing the pulpit" and was fined 2,000 marks. As he left the court he was arrested by the Gestapo and sent to Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp to be "re-educated". Niemöller refused to change his views and was later transferred to Dachau.

George Bell, the Bishop of Chichester, took up Niemöller's case. He had a series of letters published in the British press about the arrest and imprisonment of Niemöller. Bell argued that Hitler's treatment of Niemöller illustrated the attitude of the German state to Christianity. Bell's campaign helped to save Niemöller's life. It was later discovered that in 1938 Joseph Goebbels urged Adolf Hitler to have Niemöller executed. Alfred Rosenberg argued against the idea as he believed it would provide an opportunity of people like Bishop Bell to attack the German government. Hitler agreed and Niemöller was allowed to live.

Niemöller remained a German nationalist and on the outbreak of the Second World War he wrote to Admiral Erich Raeder offering to serve in the German Navy. The letter was passed to Joseph Goebbels who dismissed the idea as he believed it was an attempt by Niemöller to save his life. Goebbels now leaked the latter to undermine Niemöller's credibility. Niemöller's supporters retaliated by claiming the letter was a forgery. This version was believed and Niemöller became a symbol in Britain of resistance in Nazi Germany.

While he was in Dachau his youngest daughter Jutta died of diphtheria. On 28th February his eldest son was killed in battle in Pomerania. Another son was captured by the Red Army while fighting on the Eastern Front.

In 1945, with the Allies moving in on Germany, Niemöller, Alexander von Falkenhausen, Kurt von Schuschnigg, Leon Blum, and other political prisoners were transferred to Tirol in Austria by the SS. The original plan was to execute them but they were rescued by the Allies just before the end of the Second World War.

On 5th June 1945 Martin Niemöller gave a press conference in Naples. He admitted that he had offered to join the German Navy in 1939. He also confessed that he had "never quarrelled with Hitler over political matters, but purely on religious grounds". This resulted in a savage attack on Niemöller from those newspapers that had presented him as a symbol of resistance to Hitler's government. It was now pointed out that Niemöller had never opposed the Nazi racial theories, but merely the suppression of the Church in Germany.

When it was suggested that Niemöller wanted to visit Britain there was a campaign to keep him out of the country. Tom O'Brien of the TUC General Council wrote: "I sincerely hope he will not be allowed to come. If he is, it will be the first overt move of the Germans to "organise sympathy", as they did so successfully and so hypocritically after the last war. Niemöller commanded a U-boat in the last war and, with his brother commanders, was responsible for the drowning of many unarmed British merchant seamen. In this war he volunteered to serve under Hitler. He was (and may now be) as nationalistic as any of his congregation at the fashionable Berlin church to which he ministered."

The Archdeacon of Lancaster claimed that "the pastor's visit at this time can do nothing but harm". The Daily Telegraph pointed out that Niemöller should be denied entry as there was "no record that he ever denounced Hitler's crimes against humanity or condemned the war". The Home Secretary agreed and announced that Niemöller would not be allowed to visit Britain.

After the war Niemöller became one of the leaders of the Evangelical Church in Germany. After visiting the Soviet Union Niemöller joined the World Peace Movement. On his return to Germany he pointed out: "I cannot accept communism, but I must admit that its ideals are very different from ours, which are all tangled up with the most sordid materialism." Niemöller wrote to his friend Karl Barth explaining that he was gradually being converted to the idea of socialism: "The corner-stone of my thinking is that the root of every evil development is money." Later he wrote that " the rich must be smashed in order to build human brotherhood."

Niemöller also spoke out against the development of the Cold War. In a speech he made in New York he argued: "I am... against the often-heard statement that a war against bolshevism is necessary to save the Christian churches and Christianity. But it is unchristian to conduct a war for the saving of the Christian church, for the Christian church does not need to be saved. The church is not afraid of bolshevism. It was not afraid of Nazism. The church has to serve the communists as well as all human beings. While the church rejects communism as a creed, just as it rejects all other creeds, communism must and can only be fought and defeated with spiritual weapons. All other powers will fail."

Niemöller was a strong opponent of nuclear weapons. He thought the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was immoral. He upset the American government when he stated that after Adolf Hitler, he thought that Harry S. Truman "was the greatest murderer in the world."

In June 1954 Niemöller met Otto Hahn. The two men discussed the latest nuclear developments. Niemöller was shocked when Hahn told him that it was now possible to produce an atomic device that "would end not only all human life on earth, but also the life of every higher organism." That night he re-read the Sermon on the Mount and decided he could no longer justify the use of military force for political ends and became a pacifist.

Niemöller praised the new Japanese Constitution: "The renunciation of war as expressed in the Japanese Constitution has given a first ray of hope to a world in darkness and despair." In April 1958 he travelled to England and took part in the march to Aldermaston that had been organized by the recently formed Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. He also campaigned against military alliances such as NATO.

On 7th August, 1961 Niemöller was involved in a car crash. His wife, Else Niemöller was killed but as soon as he recovered from his injuries he returned to his campaign for world peace. He became an active member of the World Peace Committee and was for seven years president of the World Council of Churches. He also published a book on his political views entitled One World or No World (1964).

In 1965 Niemöller upset the United States by visiting North Vietnam and meeting Ho Chi Minh. Afterwards he commented: "One thing is clear, the president of North Vietnam is not a fanatic. He is a very strong and determined man, but capable of listening, something that is very rare in a person of his position." Niemöller won several awards for his work for world peace including the Lenin Peace Prize (1967) and the Grand Cross of Merit (1971). He married his second wife, Sybil von Sell, in 1971.

On his 90th birthday in 1982 Niemöller stated that he had started his political career as "an ultra-conservative who wanted the Kaiser to come back; and now I am a revolutionary. I really mean that. If I live to be a hundred I shall maybe be an anarchist." Martin Niemöller died in Wiesbaden, Germany, on 6th March, 1984.

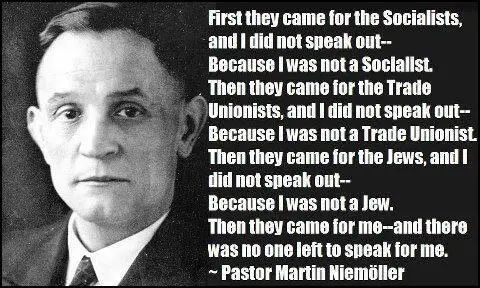

Since his death Martin Niemöller has achieved a great deal of fame for a poem entitled First they Came for the Communists. However, there is some dispute about when Niemöller wrote the poem and whether it has been altered by others over the years.

Niemöller's biographers, Dietmar Schmidt (1959) and James Bentley (1984) do not mention the poem. When it appears in books the origins of the poem are rarely given. A couple of sources claim that according to Niemöller’s wife, Sybil Niemöller, the poem dates back to a meeting with a group of students in 1946. One student asked: “How could it happen?” The story claims that Niemöller answered the question with the poem. The fact that Sybil Niemöller is quoted as the source of the story suggests that the poem emerged after the death of Martin Niemöller. This also helps to explain why it is not included in the books by Schmidt and Bentley.

The impression is given that his wife was at the meeting. This may have been true but that would have been Else Niemöller, his first wife. Else was killed in a car crash in 1961. Martin Niemöller did not marry Sybil von Sell until 1971. She was only a child at the time and was obviously not at the meeting she refers to in 1946. Research carried out by Harold Marcuse suggests that the poem was indeed written in 1946.

On this day in 1896 John Dos Passos, the illegitimate son of a prominent American attorney, John Randolph Dos Passos Jr., was born in Chicago. His mother was Lucy Addison Sprigg Madison. Alan Wald has argued: "Dos Passos spent his early years traveling semi-clandestinely about the United States and abroad with his mother. It was to these unusual circumstances of his birth and childhood that he would later attribute his lifelong sense of rootlessness."

Eventually the family settled in Virginia. His father paid for his education and he was sent to The Choate School in Wallingford, Connecticut in 1907. He also traveled with a private tutor on a six-month tour of France, England, Italy, Greece, and the Middle East to study classical art, architecture, and literature.

John Randolph Dos Passos Jr., married Lucy Addison Sprigg Madison in 1910. It was another two years before he acknowledge him until two years later. In 1912 he attended Harvard University. Dos Passos was keen to take part in the First World War and in July 1917 he joined the Norton-Harjes Ambulance Corps. Over the next few months he worked as a driver in France and Italy.

Afterwards he drew upon these experiences in his novels, One Man's Initiation (1920) and Three Soldiers (1921). This established the "pre-dominant anti-war and semi-anarchist themes of his radical period." In 1922 Dos Passos published a collection of essays, Rosinante to the Road Again, and a volume of poems, A Pushcart at the Curb. However, his literary reputation was established with his well-received novel Manhattan Transfer (1925).

As well as writing plays such as The Garbage Man (1926), Airways (1928) and Fortune Heights (1934), Dos Passos contributed articles for left-wing journals such as the New Masses, that was under the control of the American Communist Party.

In 1927 he joined with other artists such as Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Ben Shahn, Floyd Dell in the campaign against the proposed execution of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. This included the writing of Facing the Chair: Sacco and Vanzetti (1927).

Dos Passos traveled to Harland County with a Communist-initiated delegation to investigate the condition of striking miners. While in Kentucky he was arrested and charged with "criminal syndicalism". In the 1932 Presidential Election he publicly endorsed William Z. Foster, the American Communist Party candidate.

The 1930s saw the publication of his USA trilogy: The 42nd Parallel (1930), 1919 (1932) and The Big Money (1936). Dos Passos developed the experimental literary device where the narratives intersect and continue from one novel to the next. The USA trilogy also included what became known as newsreels (impressionistic collections of slogans, popular song lyrics, newspaper headlines and extracts from political speeches).

Dos Passos was active in the campaign against the growth of fascism in Europe. He joined other literary figures such as Dashiell Hammett, Clifford Odets, Lillian Hellman and Ernest Hemingway in supporting the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War. He went to Madrid where he met Marion Merriman. Later she recalled: " I was fascinated by Dos Passes, whom I had always thought was a better writer than Hemingway. John Dos Passes was, without question, a seasoned writer of the prose of war. But as a man, he didn't impress me. I thought he was wishy-washy. I couldn't make out everything he was saying, but his message was clear - for whatever reasons, he wanted out of there, out of Hemingway's room, out of bomb-shaken Madrid."

Dos Passos was disillusioned by what he saw in Spain and in 1938 he commented: "I have come to think, especially since my trip to Spain, that civil liberties must be protected at every stage. In Spain I am sure that the introduction of GPU methods by the Communists did as much harm as their tank men, pilots and experienced military men did good. The trouble with an all powerful secret police in the hands of fanatics, or of anybody, is that once it gets started there's no stopping it until it has corrupted the whole body politic. I am afraid that's what's happening in Russia."

His new political views were reflected in his novels, The Adventures of a Young Man (1939) and Number One (1943). He now moved steadily to the right, becoming an associate of The National Review and the Young Americans for Freedom. He also campaigned for Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon.

Other books by Dos Passos include the novels, The Grand Design (1949), Chosen Country (1951) and Midcentury (1961), a biography, The Head and Heart of Thomas Jefferson (1954) and an autobiography, The Best of Times: An Informal Memoir (1966). John Dos Passos died in Baltimore, Maryland, on 28th September, 1970.

On this day in 1909 Clara Mordan presented Emmeline Pankhurst with a necklace on her release from prison. Clara Mordan, the daughter of a prosperous manufacturer of propelling pencils, was born in South Kensington on 28th September 1844. She became a supporter of women's suffrage after hearing John Stuart Mill make a speech on the subject in 1866. Mordan attended several public meetings on the enfranchisement of women before joining the Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage in 1888. In 1900 Clara Mordan became a member of the executive committee of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage. Her father died in 1901, leaving an estate that was worth £117,864.

Mordan had been a loyal supporter of the policies of the National Union of Suffrage Societies but in 1906, after hearing a speech by Annie Kenney, she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). She later told Mary Blathwayt that she was convinced by "the beautiful and simple way in which Annie Kenney laid the case before her."

In her autobiography, Memories of a Militant (1924), Annie Kenney confirms that "Miss Mordan attended the first WSPU meeting held in Caxton Hall... and afterwards sent £20 towards expenses... I went to see her and she became one of our most loyal members and most generous subscribers." According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "By February 1907 Clara Mordan had given at least £172 to the WSPU; in July 1907 she gave a further £10; in 1908-09 a total of £577; in April 1909 a further £100 to be towards the cost of the Prince's Rink Exhibition; £60 in October 1909, and a further £100 in December, specifically for the General Election Fund, a further £100 in March 1910, and £200 in June 1912 to support the renewal of militancy."Mordan also made several speeches on behalf of the WSPU. This included public meetings in Bristol and Plymouth in 1908.

Clara Mordan stayed at Eagle House at Batheaston, the home of Mary Blathwayt. Others who spent time at Blathwayt's house included Christabel Pankhurst, Jessie Kenney, Annie Kenney, Clara Codd, Helen Watts, Elsie Howey, Constance Lytton and Vera Wentworth. Colonel Blathwayt photographed the women. These were then signed and sold at WSPU bazaars. He also invited them to plant a tree to commemorate their prison sentences and hunger strikes.

Clara Mordan was suffering from tuberculosis and was unable to do anything that meant she was sent to prison. On 21st October 1910 she had a letter published in Votes for Women in which she wrote that "I have impressed upon my doctor that she really must keep me alive till I can have a reasonable prospect of feeling that my last bed will be a coffin some woman has earned her living by making."

Other organisations that Mordan supported included New Constitutional Society, Tax Resistance League, National Political League and the Church League for Women's Suffrage. She also contributed towards the expenses of George Lansbury when in October 1912 he resigned his seat in the House of Commons and fighting a by-election in favour of votes for women. Lansbury discovered that a large number of males were still opposed to equal rights for women and he was defeated by 731 votes.

Clara Mordan, who never married, died on 22nd January 1915 at 18 Marine Mansions, Bexhill, East Sussex. She left most of her money to the woman she lived with, Mary Gray Allen.

On this day in 1909 war hero Peter Churchill, the son of a consular officer, was born in Amsterdam. He attended Cambridge University where he was an outstanding athlete and played for his country at hockey.

During the Second World War he became an intelligence officer and eventually joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE). In January 1942 he was sent to occupied France where he supplied money to the Maquis and assessed the potential for helping the French Resistance. After returning to England he was promoted to captain.

Churchill returned to France in August 1942 where he helped Andre Girard establish the Spindle Network. Odette Sansom was recruited as the group's radio operator. The main object of this network was to help direct aerial delivery of arms and ammunition for the Maquis.

The Spindle Network was infiltrated by spies and on 16th April, 1943, Churchill and Sansom were arrested by Hugo Bleicher of Abwehr. They claimed they were husband and wife and related to Winston Churchill. They hoped that this story would help them receive better treatment while in prison.

Both Churchill and Sansom were tortured by the Gestapo before being sent to concentration camps. However, they were not executed and they were both still alive when liberated by the Allies at the end of the war.

Churchill and Odette Sansom were married in 1947 but divorced in 1955. Churchill wrote several books about his wartime experiences including Of Their Own Choice (1952), Duel of Wits (1953), The Spirit of the Cage (1954) and By Moonlight (1958). Peter Churchill died in 1972.

On this day in 1923 Frederic Harrison died. Harrison, the son of a prosperous stockbroker, was born in London on 18th October 1831. After being educated at King's College School and Wadham College, Oxford, where he obtained a first-class degree. In 1855 he read law at Lincoln's Inn and in 1858 was called to the Bar.

Harrison developed radical political views after reading the work of John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle. He was also influenced by the the ideas of the Christian Socialists and in 1859 began lecturing at the Working Men's College. Harrison gave support to George Potter and his building workers during their industrial disputes in the early 1860s. He began a regular contributor to trade union and radical journals. In these articles he argued that trade unions represented working-class democracy in action.

When the head of the Conservative government, Earl of Derby decided to set up a Royal Commission on Trade Unions in 1867, George Potter, writing for the Bee-Hive, called for a working man to be included or a "gentleman well known to the working classes as possessing a practical knowledge of the working of Trade Unions, and in whom they might feel confidence." The government rejected the idea of a working man but they did ask Frederic Harrison to serve on the commission. Harrison was a very useful member of the commission, preparing union witnesses by telling them in advance what questions would be asked and rescued the from difficult situations during their cross-examination.

Robert Applegarth, the general secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners was chosen as a union observer of the proceedings. Applegarth worked hard checking the various accusations of the employers and providing information to the two pro-union members of the Royal Commission, Harrison and Thomas Hughes. Applegarth also appeared as a witness and it was generally accepted that he was the most impressive of all the trade unionists who gave evidence before the commission.

Frederic Harrison, Thomas Hughes and the Earl of Lichfield refused to sign the Majority Report that was hostile to trade unions and instead produced a Minority Report where he argued that trade unions should be given privileged legal status. Harrison suggested several changes to the law: (1) Persons combining should not be liable for indictment for conspiracy unless their actions would be criminal if committed by a single person; (2) The common law doctrine of restraint of trade in its application to trade associations should be repealed; (3) That all legislation dealing with specifically with the activities of employers or workmen should be repealed; (4) That all trade unions should receive full and positive protection for their funds and other property.

The Trade Union Congress campaigned to have the Minority Report accepted by the new Liberal government headed by William Gladstone. This campaign was successful and the 1871 Trade Union Act was based largely on the Minority Report.

The trade union movement was very pleased with the work that Frederic Harrison had done on the Royal Commission and he was offered the editorship of the Bee-Hive. Harrison declined but over the years wrote thirty-two articles for the paper. He also continued to give legal advice to unions in dispute with the law. Harrison was also active in the Reform League where he argued for adult suffrage.

In 1889 Frederic Harrison was appointed alderman of the new London County Council. Harrison sat with the ruling Progressive Party that included John Burns, John Benn, Sidney Webb, Harry Gosling and Ben Tillett. Harrison also served as chairman of the LCC's Improvements Committee.

Harrison wrote a large number of books during his life including: William Cromwell (1888), Studies in Early Literature (1895), John Ruskin (1902), Autobiographic Memoirs (1911), The Positive Evolution of Religion (1913), The Meaning of War for Labour (1914) and Jurisprudence and the Conflict of Laws (1919).

On this day in 1925 cartoonist Harry Furniss died in Hastings. Harry Furniss, the son of an English engineer, was born in County Wexford, Ireland, on 26th March 1854. His mother was the miniaturist painter Isabella Mackenzie. After leaving school he worked as a clerk to a wood-engraver, who taught him the trade.

Furniss worked as an artist in Ireland but in 1876 he moved to England and found work with the Illustrated London News. Over the next eight years he developed a reputation as an outstanding draughtsman. He also contributed to The Pall Mall Gazette, The Daily News, The Sketch, Vanity Fair, and The Graphic.

In October 1880, Francis Burnand, the editor of Punch Magazine, invited Furniss to contribute to the magazine. Several of his cartoons were published and in 1884 he became a member of the staff at the magazine. For the next ten years he illustrated the "Essence of Parliament". He also supplied articles, jokes, illustrations and dramatic criticisms for other sections of the magazine. It is estimated that over the years he contributed more than 2600 drawings to the magazine.

Harry Furniss always drew William Gladstone with a large collar, and although he never wore collars like this, the public become convinced that he did. Furniss was a staunch Unionist and he was especially harsh on Irish Nationalists. One MP, Swift MacNeill, who was portrayed as a gorilla, was so angry with that he physically assaulted Furniss. Another group of MPs threatened him with a beating unless he ended his campaign against them.

Harry Furniss work became extremely popular with the British public and this enabled him to tour the country giving lectures on subjects such as "The Frightfulness of Humour" and "Humours of Parliament". Furniss also illustrated a great number of books including those by Lewis Carroll, Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray.

Mark Bryant has pointed out: "He rarely used an easel but preferred to work standing up at a waist-high desk. He drew in pen and ink but also worked in chalk and painted in watercolours and oils." R.G.G. Price, the author of A History of Punch (1957) has argued that Furniss was "not a great draughtsman... but a very experienced pictorial journalist who could work fast and get a likeness easily. It is said that he would chat to a man and caricature him on a pad held in his pocket".

Harry Furniss left Punch Magazine in 1894 after a discovered that the magazine had sold the copyright of one of his drawings to Pears Soap for advertising. Furniss had for a long time wanted his own business and that year he started his own cartoon magazine, Like Joka. It sold 140,000 copies on its first day. However, the magazine was not a long-term financial success and he moved to the USA where he worked in the film industry with Thomas Edison. Furniss helped pioneer the animated cartoon films with War Cartoons (1914) and Peace and Pencillings (1914).