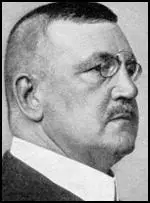

Wolfgang Kapp

Wolfgang Kapp was born in New York City on 24th July, 1858. His father, Friedrich Kapp, had been involved in the failed 1848 German Revolution and had emigrated to the United States in 1849.

His father joined the law firm of Zitz, Kapp and Froebel. However, in 1852, he became a journalist and worked as a foreign correspondent for the Kölnische Zeitung, a newspaper in Cologne. He also contributed to The Nation. A strong opponent of slavery he joined the Republican Party and in 1860 campaigned for Abraham Lincoln. It is claimed that except for Carl Schurz, no one did more to win German-Americans over to supporting the Union Army during the American Civil War.

In 1870, Friedrich Kapp decided to return to Germany with his twelve year-old son. The family settled in Berlin and Wolfgang was educated at the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Gymnasium. He studied law at the University of Tübingen but before he graduated he married Margarete Rosenow. She came from a conservative family and he gradually left behind the radicalism of his father. After leaving university Kapp worked in the Finance Ministry and later managed an estate in East Prussia. Kapp became the founder of the Agricultural Credit Institute which achieved great success in promoting the needs of landowners and farmers in that province.

During the First World War he developed right-wing views and was one of the leading critics of Chancellor Theobold von Bethmann-Hollweg. In 1917 he joined forces with Alfred von Tirpitz to establish the German Fatherland Party. By the summer of 1918 it had around 1,250,000 members. The party was dissolved after the German Revolution at the end of the war. The following year he was elected to the Reichstag where he campaigned for the restoration of Kaiser Wilhelm II. In August 1919 he helped General Erich Ludendorff and Waldemar Pabst to establish the Nationale Vereinigung (National Union), which campaigned for a counter-revolution to install a form of conservative militaristic government.

In March 1920, according to the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, the Germans were obliged to dismiss between 50,000 and 60,000 men from the armed forces. Among the units to be disbanded was a naval brigade commanded by Captain Herman Ehrhardt, a leader of a unit of Freikorps. The brigade had played a role in crushing the Bavarian Socialist Republic in May, 1919.

On the evening of 12th March, 1920, the Ehrhardt brigade went into action. He marched 5,000 of his men twelve miles from their military barracks to Berlin. The Minister of Defence, Gustav Noske, had only 2,000 men to oppose the rebels. However, the leaders of the German Army refused to put down the rebellion. General Hans von Seeckt informed him "Reichswehr does not fire on Reichswehr." Noske contacted the police and security officers but they had joined the coup themselves. He commented: "Everyone has deserted me. Nothing remains but suicide." However, Noske did not kill himself and instead fled to Dresden with Friedrich Ebert. However, the local military commander, General George Maercker refused to protect them and they were forced to travel to Stuttgart.

Captain Herman Ehrhardt met no resistance as they took over the ministries and proclaimed a new government headed by Wolfgang Kapp. Berlin had been seized from the German Social Democrat government. However, the trade union leaders refused to flee and Carl Legien called for a general strike to take place. As Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982), has pointed out: "The appeal had an immediate impact. It went out at 11am on the day of the coup, Saturday 13 March. By midday the strike had already started. Its effects could be felt everywhere in the capital within 24 hours, despite it being a Sunday. There were no trains running, no electricity and no gas. Kapp issued a decree threatening to shoot strikers. It had no effect. By the Monday the strike was spreading throughout the country - the Ruhr, Saxony, Hamburg, Bremen, Bavaria, the industrial villages of Thuringia, even to the landed estates of rural Prussia."

Louis L. Snyder has argued: "The strike was effective because without water, gas, electricity, and transportation, Berlin was paralyzed." A member of the German Communist Party (KPD) argued: "The middle-ranking railway, post, prison and judicial employees are not Communist and they will not quickly become so. But for the first time they fought on the side of the working class." Five days after the putsch began, Wolfgang Kapp announced his resignation and fled to Sweden.

Wolfgang Kapp returned to Germany in 1922 to stand trial for treason, but died of cancer in prison on 12th June, 1922.