On this day on 13th February

On this day in 1542 Catherine Howard, the fifth wife of Henry VIII, is executed for adultery. Henry married Catherine on 8th August 1540 at Hampton Court. The historian David Starkey, has attempted to explain the reasons for the marriage: "Physically repelled by Anne of Cleves, and humiliated by his sexual failure with her, he sought and found consolation from Catherine. We can also guess that sex, which had been impossible with Anne, was easy with her. And it was easy because she made it easy. Henry, lost in pleasure, never seems to have asked himself how she obtained such skill. Instead, he attributed it all to love and his own recovered youth."

Henry VIII showered her with "magnificent jewels, gold beads decorated with black enamel, emeralds lozenged with gold, brooches, crosses, pomanders, clocks, whatever could be most splendidly encrusted in her honour". Soon after the wedding he gave her a habiliment containing "eight diamonds and seven rubies" and a necklace of "six fine table diamonds and five very fair rubies with pearls in-between" and a muffler of black velvet with thirty pearls on a chain of gold.

Historians have only been able to identify one portrait, painted by Hans Holbein, that is definitely of Catherine of Howard. "Dispute has raged as to whether its subject really is Catherine. But the identification of the jewels settles the issue once and for all. It also establishes, for the first time, her exact appearance. She had auburn hair, pale skin, dark eyes and brows, the rather fetching beginnings of a double chin, and an expression that was at once quizzical and come-hither."

Richard Hilles saw Catherine in the summer of 1540. He described her as "a very little girl". Alison Weir has suggested that this may refer to her diminutive stature, it could also refer to her age, as it conveys a distinct impression of extreme youth." Catherine was over a foot smaller than Henry. The French ambassador, Charles de Marillac, rated her beauty as only "middling" but did praise her gracefulness, and found "much sweetness in her expression". Antonia Fraser points out that as she immediately attracted Henry "she must have considerable prettiness and obvious sex appeal"

On 17th January, 1541, Henry ordered the arrest of Thomas Wyatt and Ralph Sadler. Both men had been close friends of Thomas Cromwell and were seen as religious reformers. The following month, Sir John Wallop, the conservative former ambassador to France, was also arrested. Charles de Marillac predicted a civil war in England: "There could be no worse war than the English carry on against each other... For after Cromwell had brought down the greatest of the realm... now others have arisen who will never rest till they have done as much to all Cromwell's adherents."

All three men were eventually released. Eustace Chapuys claims "the Queen took courage to beg and entreat the King for the release of Mr. Wyatt, a prisoner of the Tower." David Starkey provides evidence that Catherine was involved in obtaining the release of all three men. "Catherine, like many teenagers, certainly showed herself to be wilful and sensual. But she also displayed leadership, resourcefulness and independence, which are qualities less commonly found in headstrong young girls... True, she was a good-time girl. But, like many good-time girls, she was also warm, loving and good-natured. She wanted to have a good time. But she wanted other people to have a good time, too. And she was prepared to make some effort to see that they did... Catherine, in short, had begun rather well. She had a good heart, and a less bad head than most of her chroniclers have assumed."

However, Queen Catherine was unable to save the life of Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury. Henry VIII had ordered her arrest in May 1539. She had been considered one of the leading Roman Catholics in England. However, the only evidence against her was that she had forbidden her servants to read the English Bible, and had once been seen burning a letter. Margaret was the daughter of George, Duke of Clarence, who was the brother of Edward IV and Richard III. She therefore had a valid claim to the throne.

On 28th May, 1541, Henry gave orders for the 68-year-old Countess to be executed. It has been called one of the worst atrocities of Henry's reign. "The executioner was not the usual one employed on such occasions and was young and inexperienced. Faced with such a prisoner, he panicked, and struck out blindly, hacking at his victim's head, neck and shoulders, until he had finally butchered her to death."

During this period Catherine appointed her former lover, Francis Dereham, as her secretary and usher of the chamber. She later insisted that this appointment was on the urging of her step-grandmother, Duchess Agnes Howard. However, according to Retha M. Warnicke, it was possible she was being blackmailed: "It was probably intended to silence him, too, about their former relationship. She could reasonably hope for success in this, for Dereham later confessed that on two occasions she bribed him to hold his tongue."

In June 1541 Henry VIII took Queen Catherine on a tour of the Northern counties. Although he had been power for 32 years he had not visited this part of England that made up a third of his kingdom. He took with him an army of 5,000 men. Progress was slow as it was a very wet summer. Charles de Marillac reported that "the roads leading to the North... have been flooded and the carts and baggage could not proceed without great difficulty." (45) The Court lingered in Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire for most of July.

They did not reach Lincoln until 9th August. The royal couple stayed at the Bishop of Lincoln's little manor house at Lyddington. On 11th August, Catherine committed the first of her indiscretions. She knew Thomas Culpeper, was in the area and she wrote him a letter: "Master Culpeper, I heartily recommend me unto you... I never longed so much for thing as I do to see you and to speak with you... It makes my heart to die to think what fortune I have that I cannot be always in your company... Come when my Lady Rochford is here, for that I shall be best at leisure to be at your commandment... Yours as long as life endures."

Catherine's biographer, Retha M. Warnicke, has argued: "It is possible, however, to put a different interpretation upon Catherine's letter, that its emotional tone was fuelled less by sexual ardour than by the desperation of a young woman who was seeking to placate an aggressive, dangerous suitor, one who, moreover, as a member of the privy chamber had close contact with the king. The promise she mentioned could have concerned the Dereham affair. Culpeper, it may be suggested, had established some form of threatening control over the queen's life, and although he - as he admitted - was seeking sexual satisfaction with her, Catherine was trying to ensure his silence through a misguided attempt at appeasement." Jasper Ridley claims that Catherine met Culpeper in Lady Rochford's room in the middle of the night, while Henry was sleeping off the effects of his usual large supper.

The route of the Royal Progress turned inland towards Yorkshire the scene of the Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion a few years previously. Henry spent a few days hunting at Hatfield Chase. It contained ponds and marshes as well as scrub and woodland. Men in boats went on to the water where others hunted in the woods. It is estimated that over 200 stags and deer were killed as well as "a great quantity of young swans, two boats of river birds and as much of great pikes and other fish."

Henry VIII then moved to Pontefract Castle. According to the French ambassador who accompanied Henry, the castle was visited by the nobility and gentry who lived in Yorkshire: "Those who in the rebellion remained faithful were ranked apart and graciously received by the King and praised for their fidelity. The others who were of the conspiracy, among whom appeared the Archbishop of York, were a little further off on their knees... One of them, speaking for all, made a long harangue confessing their treason in marching against the sovereign and his Council, thanking him for pardoning so great an offence and begging that if any relics of indignation remained he would dismiss them. They then delivered several bulky submissions in writing."

Henry VIII and his party visited York before retuning to London. He arrived back at Hampton Court on 29th October. While the King had been away Archbishop Thomas Cranmer had been contacted by John Lascelles. He told him a story that came from his sister, Mary Hall, who had worked as a maid at Chesworth House. She claimed that while in her early teens Catherine had "fornicated" with Henry Manox, Francis Dereham and Thomas Culpeper.

Cranmer had never approved Henry's marriage to Catherine. He did not personally dislike her but he was a strong opponent of her grandfather, Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk. If Lascelles's story was true, it gave him the opportunity to discredit her supporters, the powerful Catholic faction. With her out of the way Cranmer would be able to put forward the name of a bride who like Anne Boleyn favoured religious reform.

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer had a meeting with Mary Hall. She told him that when she heard about Catherine's relationship with Manox in 1536 she went to see him and warned him of his behaviour. Manox replied: "Hold thy peace, woman! I know her well enough. My designs are of a dishonest kind, and from the liberties the young lady has allowed me, I doubt not of being able to effect my purpose. She hath said to me that I shall have her maidenhead, though it be painful to her, not doubting but I will be good to her hereafter." Hall then told of Catherine's relationship with Dereham. She claimed that for "a hundred nights or more" he had "crept into the ladies dormitory and climbed, dressed in doublet and hose" into Catherine's bed.

On 2nd November, 1541, Archbishop Cranmer, presented a written statement of the allegations to Henry VIII. Cranmer wrote that Queen Catherine had been accused by Hall of "dissolute living before her marriage with Francis Dereham, and that was not secret, but many knew it." Henry reacted with disbelief and told Cranmer that he did not think there was any foundation in these malicious accusations; nevertheless, Cranmer was to investigate the matter more thoroughly. "You are not to desist until you have got to the bottom of the pot." (55) Henry told Thomas Wriothesley that "he could not believe it to be true, and yet, the accusation having once been made, he could be satisfied till the certainty hereof was known; but he could not, in any wise, that in the inquisition any spark of scandal should arise against the Queen."

Henry also gave orders that Catherine Howard was to be confined to her apartments with just Jane Boleyn (Lady Rochford) in attendance. Eustace Chapuys told Charles de Marillac that she was refusing to eat or drink anything, and that she did not cease from weeping and crying "like a madwoman, so that they must take away things by which she might hasten her death". It was also reported that Lady Rochford was guilty of aiding and abetting Catherine to commit high treason.

Sir Richard Rich and Sir John Gage were given the task of questioning Thomas Culpeper, Francis Dereham and Henry Manox. According to Alison Weir, the author of The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007) Rich and Gage "had supervised the torturing, with instructions to proceed to the execution of the prisoners, if they felt that no more was to be gained from them by further interrogation."

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer visited the Queen in her apartments on 6th November. His main objective was to obtain a confession that she had committed adultery. Without it, no one could proceed against her, for pre-marital fornication was neither a crime nor acceptable grounds for annulling a marriage. He found the Queen "in such lamentation and heaviness as I never saw no creature, so that it would have pitied any man's heart in the world to have looked upon".

Unable to get much sense out of the Queen he returned the following day. Cranmer told her that if she made a full confession the King would probably show mercy. She eventually confessed that Francis Dereham called her "wife" and she used the term "husband" and that it was common gossip in the household that they would marry. He had "many times moved me unto the question of matrimony" but she refused all his proposals. Catherine made a serious mistake with this confession. Under the law of the time, if she had made a pre-contract of marriage with Dereham, her marriage to Henry was invalid and therefore she could not be convicted of adultery.

Queen Catherine admitted that she had on many occasions gone to bed with Dereham. "He hath lain with me, sometimes in his doublet and hose, and two or three times naked, but not so naked that he had nothing upon him, for he had always at the least his doublet, and as I do think his hose also; but I mean naked, when his hose was put down." Catherine claimed that she had not willingly had sexual intercourse with Dereham and that he had raped her with "importunate force". Catherine admitted that the last time she saw Dereham was in 1539. He said he had heard a rumour that she was romantically involved with Thomas Culpeper and the couple were about to marry. She replied: "What should you trouble me thereabouts, for you know I will not have you; and if you heard such report, you know more than I." This was the first time that Thomas Culpeper's name had been mentioned. Archbishop Cranmer knew that Culpeper was a highly favoured gentleman of the King's Privy Chamber. Cranmer was searching for someone who had committed adultery with the Queen. Cranmer now had another candidate and he ordered the arrest and questioning of Culpeper.

Catherine Howard also confessed about her relationship with Henry Manox. "My sorrow I can by no writing express, nevertheless I trust your most benign nature will have some respect unto my youth, my ignorance, my frailness, my humble confession of my faults and plain declaration of the same, referring me wholly unto your Grace's pity and mercy. First at the flattering and fair persuasions of Manox, being but a young girl I suffered him at sundry times to handle and touch the secret parts of my body, which neither became me with honesty to permit, nor him to require."

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer thought this confession would please Henry VIII as he could now see his marriage to Catherine was invalid and he would be free to marry again. However, Henry wanted more time to think about the situation. He therefore ordered Catherine to be sent to the former Abbey of Syon at Brentford. He also told Cranmer to arrange for all those who were involved in the affair to be sent to the Tower of London to await questioning.

Manox was the first to be cross-examined. He told them he had been employed by the Duchess Agnes Howard to teach Catherine music and singing and admitted having tried to seduce her. When the Duchess discovered them kissing she had beaten them both and commanded that they should never to be alone together again. This had not deterred Manox, and on another occasion she had agreed he might caress her private parts. In his words he had "felt more than was convenient". However, he told his interrogators: "Upon his damnation and most extreme punishment of his body, he never knew her carnally". The Privy Council, seeing that he had committed no crime, released him.

As Kelly Hart has pointed out, Catherine was highly unlikely to have become too involved with Manox. She knew that to marry a man of his background would have been to cause her serious problems: "They (Catherine and Manox) could only have married if they had eloped, to lead an impoverished life. In an age where a woman might starve to death if she married a man of little means, Catherine was understandably aiming for someone who could keep her future children in luxury."

Thomas Wriothesley interviewed the Queen's servants. Katherine Tylney and Margaret Morton both gave evidence that Thomas Culpeper met the Queen in Lady Rochford's chamber. Morton testified that while at Pontefract Castle in August 1541, Lady Rochford locked the room from inside after both Catherine and Culpeper went inside. Morton also said that she "never mistrusted the Queen until at Hatfield I saw her look out of her chamber window on Master Culpeper, after such sort that I thought there was love between them". On another occasion the Queen was in her closet with Culpeper for five or six hours, and Morton thought "for certain they had passed out" (a Tudor euphemism for orgasm).

Jane Boleyn (Lady Rochford) was interviewed in some depth. She had previously given evidence against her husband, George Boleyn, and sister-in-law, Anne Boleyn. She claimed that at first Catherine rejected the advances of Culpeper. She quoted her as saying: "Will this never end?" and asking Lady Rochford to "bid him desire no more to trouble me, or send to me." But Culpeper had been persistent, and eventually the Queen had admitted him into her chamber in private. Lady Rochford was asked to stand guard in case the King came. Rochford added that she was convinced that Culpeper had been sexually intimate "considering all things that she hath heard and seen between them".

Antonia Fraser, the author of The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1992), is highly critical of the evidence provided by Lady Rochford: "Lady Rochford attempted to paint herself as an innocent bystander who had somehow been at the other end of the room where the Queen was meeting Culpeper, without knowing what was going on. Catherine on the other hand reversed the image and described a woman, like Eve, who had persistently tempted her with seductive notions of dalliance; while Culpeper too took the line that Lady Rochford had 'provoked' him into a clandestine relationship with the Queen... Once again, as with the technicalities of the Queen's adultery, absolute truth - and thus relative blame - is impossible to establish."

Mary Hall testified that she saw Catherine and Culpeper "kiss and hang by their bills (lips) together and as if they were two sparrows". Alice Restwood said that there was "such puffing and blowing between (Catherine and Dereham) that she was weary of the same". Margaret Benet admitted that "she looked out at a hole of a door and there saw Dereham pluck up (Catherine's) clothes above her navel so that he might well discern her body". Benet went on to say she heard the couple talk about the dangers of her becoming pregnant. She heard "Dereham say that although he used the company of a woman... yet he would get no child". Catherine replied that she also knew how to prevent having children. She told Dereham that she knew "how women might meddle with a man and yet conceive no child unless she would herself". David Starkey has asked the question: "Was this confident contraceptive knowledge? Or merely old-wives' tales? In either case, it explains why Catherine was prepared to have frequent sex with no apparent heed to the risks of pregnancy."

Thomas Culpeper appeared before the Privy Council to give evidence in his defence. He claimed that although Lady Rochford had "provoked him much to love the Queen, and he intended to do ill with her and likewise the Queen so minded to do with him, he had not passed beyond words". Edward Seymour told Culpeper that his intensions towards Queen Catherine were "so loathsome and dishonest" that in themselves they would be said to constitute high treason and so therefore he deserved to die.

The trial of Culpeper and Dereham began on 1st December, 1541 in Westminster Hall. Dereham was charged with "presumptive treason" and of having led the Queen into "an abominable, base, carnal, voluptuous and licentious life". He was accused of joining the Queen's service with "ill intent". It was claimed that Dereham once told William Damport that he was sure he might still marry the Queen if the King were dead. Under the 1534 Treason Act, it was illegal to predict the death of the King.

Culpeper was accused of having criminal intercourse with the Queen on 29th August 1541 at Pontefract, and at other times, before and after that date. During the trial Culpeper changed his plea to guilty. Dereham continued to plead his innocence but both men were found guilty. Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, sentenced them to be drawn on hurdles to Tyburn "and there hanged, cut down alive, disembowelled, and, they still living, their bowels burnt; the bodies then to be beheaded and quartered".

Charles de Marillac reported that Culpeper especially deserved to die, even though he did not admit to having full intercourse with Catherine, "for he confessed his intention to do so, and his confessed conversations, being held by a subject to a queen, deserved death". Marillac explained that Henry had "changed his love for the Queen into hatred, and taken such grief at being deceived, that of late it was thought he had gone mad". Henry also suggested that she was such a "wicked woman" that she "should have torture in her death".

Francis Dereham was tortured on 6th December. According to Thomas Wriothesley he admitted that he had said that he might "still marry the Queen if the King were dead". He also admitted having sexual intercourse with Catherine Howard in 1538 but he vehemently denied committing adultery with the Queen. Later that day, the King was asked if he would change the sentence to beheading. He agreed for Culpeper but stated that Dereham "deserved no mercy". The decision was one based on the background of the two men. Men of the higher class were rarely "hung, drawn and quartered".

Culpeper were executed on 10th December 1541. Culpeper asked the crowd to pray for him. No block had been provided. He knelt on the ground by the gallows, and was decapitated with one stroke of the axe. Dereham then suffered the full horror of being hanged, castrated, disembowelled, beheaded and quartered. Both heads were set up on pikes above London Bridge.

Henry VIII now asked Parliament to pass a new law that would enable him to order the execution of Catherine Howard. Members were told that Catherine had led "an abominable, base, carnal, voluptuous and vicious life" and had acted "like a common harlot with divers (many) persons... maintaining however the outward appearance of chastity and honesty".

The proposed new law stated that "an unchaste woman marrying the King should be guilty of high treason". Anyone concealing this information was also guilty of high treason. The proposed law also stated that any woman who presumed to marry the King without admitting she had been unchaste would merit death. The Act was passed on 16th January 1542. As David Starkey has pointed out the "key clauses of the Act were flagrantly retrospective".

Catherine Howard was told on 25th January that she could go to "the Parliament chamber to defend herself". She declined the offer and submitted herself to the King's mercy. She was visited by a deputation of members of the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Catherine told them that she deserved to die and her only care was to have a good death. She asked to have the block brought to her in advance so "that she might know how to place herself".

Eustace Chapuys reported that the "Queen is very cheerful, and more plump and pretty than ever; she is as careful about her dress and as imperious and wilful as at the time she was with the King, notwithstanding that she expects to be put to death, that she confesses she has deserved it, and asks for no favour except that the execution shall be secret and not under the eyes of the world."

On 29th January 1542, Henry gave a banquet attended by sixty-one young women. It was claimed that the women had been chosen as candidates to become the next Queen of England. Chapuys reported that "the common voice is that this King will not be long without a wife, because of the great desire he has to have further issue." It was claimed that Henry was particularly attentive to the 20-year-old Anne Bassett. It was rumoured that she had been his mistress for several years.

The Act of Attainder was passed by Parliament on 6th February 1542. Catherine Howard and Jane Boleyn (Lady Rochford) were both sentenced to death and loss of goods and lands. Henry went into the House of Commons and thanked them "for that they took his sorrow to be theirs". Chapuys told Charles V that Henry had "never been so merry since first hearing of the Queen's misconduct.

On 10th February 1542, officials arrived at the Abbey of Syon to take Catherine to the Tower of London. As soon as she learned what they had come for, she became hysterical and had to be dragged to the waiting barge. On her journey to the Tower she passed under London Bridge, where the rotting heads of Thomas Culpeper and Francis Dereham were still being displayed. The Constable of the Tower, Sir John Gage, reported that over the next couple of days Catherine "weeps, cries and torments herself miserably without ceasing".

At seven o'clock on Monday, 13th February, 1542, Catherine Howard was taken to Tower Green. Gage reported that she was so weak with crying that she could hardly stand or speak. Before her execution she said she merited a hundred deaths and prayed for her husband. According to one witness Catherine said she "desired all Christian people to take regard unto her worthy and just punishment". The executioner severed her head in a single blow.

Lady Rochford followed her to the block. Eustace Chapuys reported that she was "in a frenzy" brought on by the sight of Catherine's "blood-soaked remains being wrapped in a black blanket by her sobbing ladies". It was reported that she made an speech where she called for the preservation of the King before she placed her head "on a block still wet and slippery with her mistress's blood."

David Loades, the author of The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007) claims that Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley was unhappy with the decision to execute Catherine Howard: "Lord Chancellor Audley seems to have some qualms about it, fearing that justice might not be seen to be done, but perhaps it was felt that the spectacle of another queen on trial for substantially the same offence might have brought ridicle upon the English Crown."

On this day in 1638 John Lilburne is found guilty of publishing illegal books, and sentenced to be fined £500, whipped, pilloried and imprisoned. The following month he was whipped from Fleet Prison to Old Palace Yard. It is estimated that Lilburne received 500 lashes along the way, making 1,500 stripes to his back during the two-mile walk. An eyewitness account claimed that his badly bruised shoulders "swelled almost as big as a penny loaf" and the wheals on his back were larger than "tobacco-pipes."

When he was placed in the pillory he tried to make a speech praising John Bastwick and was gagged. Lilburne's punishment turned into an anti-government demonstration, with cheering crowds encouraging and supporting him. While in prison Lilburne wrote about his punishments, in his pamphlet, The Work of the Beast (1638). He reported on how he was tied to the back of a cart and whipped with a knotted rope.

In March 1640, Charles I was forced to recall Parliament for the first time in eleven years. Oliver Cromwell, a Puritan member of the House of Commons, made a speech about Lilburne's case. "Cromwell spoke with a great passion, thumping the table before him, the blood rising to the face as he did so. To some he appeared to be magnifying the case beyond all proportion. But to Cromwell this was the essence of what he had come to put right: religious persecution by an arbitrary court."

After a debate on the issue in November, Parliament voted to release him from prison. He was now a famous figure and his portrait was engraved by George Glover. Lilburne's supporters continued to protest about the way he had been treated and on 4th May 1641, Parliament resolved that the Star Chamber sentence against him had been "bloody, wicked, cruel, barbarous, and tyrannical", and voted him monetary reparations. Four months later he married Elizabeth Dewell.

John Lilburne continued to lead the attacks against the monarchy and the established church and on 27th December 1641 he was wounded in the New Palace Yard by musket fire when demonstrating (as he admitted) "with my sword in my hand" against bishops and "popish lords".

front-cover of a Leveller pamphlet published in 1646.

On this day in 1877 William Anderson, the son of Francis Anderson, a blacksmith, and Barbara (née Cruikshank), was born in Findon, Banffshire, Scotland. His biographer, Joseph Melling has claimed: "His mother was an intelligent and widely read woman of strong, radical, Presbyterian views who encouraged William to read extensively and passed on a love of literature which stayed with him long after he was converted to free-thinking atheism."

Educated at elementary school he was apprenticed to a manufacturing chemist. He joined the Shop Assistants' Union and in 1903 became one of its organizers. During this period he fell in love with Mary Macarthur, the secretary of the Ayr branch. Both were committed socialists and joined the Independent Labour Party. During this period he worked closely with other socialists in Glasgow including David Kirkwood, John Wheatley, Emanuel Shinwell, James Maxton, William Gallacher, John Muir, Tom Johnston, Jimmie Stewart, Neil Maclean, George Hardie, George Buchanan and James Welsh.

In 1907 Anderson moved to London. The following year he was elected to the national administration council of the Independent Labour Party in 1908, and served as its chairman (1911-14). Anderson earned his living as a journalist and in 1912 he joined forces with Ramsay MacDonald to launch The Daily Citizen.

William Anderson married Mary Macarthur on 21st September 1911. Their first child died at birth in 1913 but two years later a daughter, Anne Elizabeth, was born. Anderson was elected to the House of Commons to represent Sheffied Attercliffe in 1914. The historian, Joseph Melling, has argued: "A handsome, charming, and engaging personality, Anderson was able to attract support from different sections of the Labour Party and to avoid bitter factional disputes. He was an effective and persuasive debater, whose warmth of manner gave him an advantage over Ramsay MacDonald."

On the outbreak of the First World War, Anderson and Macarthur opposed military conflict. Anderson also supported the Clyde Workers' Committee and organisation that had been formed to campaign against the Munitions Act, which forbade engineers from leaving the works where they were employed. David Lloyd George and Arthur Henderson met the Clyde Workers' Committee in Glasgow on 25th December 1915 but they were unwilling to back down on the issue.

On 25th March 1916, David Kirkwood and other members of the Clyde Workers' Committee were arrested by the authorities under the Defence of the Realm Act. Then men were court-martialled and sentenced to be deported from Glasgow. Anderson severely criticised this decision in the House of Commons.

Anderson, like most anti-war candidates, was defeated in in the 1918 General Election. Anderson died of influenza on 25th February 1919.

On this day in 1906 Robert Sherriffs was born in Arbroath. After studying at the Edinburgh College of Arts he began having his cartoons published in The Bystander, The Strand Magazine and The Sketch. In 1934 he drew a weekly cartoon for the Radio Times. In 1944 he published the comic novel, Salute If You Must.

After the Second World War Sherriffs was expected to become staff cartoonist on the Daily Herald but this went to his friend, George Whitelaw, instead. In 1948 he succeeded James Dowd as film caricaturist on Punch Magazine. He claimed "I regarded caricatures as designs and the expressions on faces merely as changes in a basic pattern."

Robert Sherriffs died on 26th December 1960.

On this day in 1907 the Women's Social & Political Union (WSPU) organized the first Women's Parliament at Caxton Hall. The women were confronted by mounted police. Fifty-eight women appeared in court as a result of the conflict. Most of those arrested received seven to fourteen days in Holloway Prison, though Sylvia Pankhurst and Charlotte Despard got three weeks.

Nellie Martel, Emmeline Pankhurst and Charlotte Despard.

On this day in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established a secret "special intelligence unit" under John Franklin Carter. The historian, Joseph E. Persico, the author of Roosevelt's Secret War (2001), claims that President Roosevelt arranged for plausible deniability. Carter later admitted: "The overall condition was attached to the operation by President Roosevelt that it should be entirely secret and would be promptly disavowed in the event of publicity... That year's military appropriations act included an Emergency Fund for the President, from which FDR transferred $10,000 to the State Department... to finance Carter, ostensibly by buying from him surveys on conditions in various countries, with Germany leading the list.... By the end of 1941 Carter... was operating with $54,000 from the President's emergency funds."

Adolf Berle was placed in charge of distributing the funds. On 20th February, Berle recorded: "Jay Franklin (J.F. Carter) came in to see me today. He stated as a result of his conversation with the President and with you, and preparatory to the work he had been asked to do, he had spent some seven hundred dollars, and that he would be broke by the end of this week... He wanted an advance of some kind against the compensation which he would eventually receive for his work. Accordingly I lent him seven hundred dollars... I am not, of course, familiar with what the President has asked him to do, nor do I wish to be."

One of Carter's first tasks was to deal with Charles Lindbergh, one of the leaders of the American First Committee. Roosevelt was furious with Lindbergh after a speech he made on 23rd April, which included the following: "It is not only our right but it is our obligation as American citizens to look at this war objectively and to weigh our chances for success if we should enter it. I have attempted to do this, especially from the standpoint of aviation; and I have been forced to the conclusion that we cannot win this war for England, regardless of how much assistance we extend. I ask you to look at the map of Europe today and see if you can suggest any way in which we could win this war if we entered it. Suppose we had a large army in America, trained and equipped. Where would we send it to fight? The campaigns of the war. show only too clearly how difficult it is to force a landing, or to maintain an army, on a hostile coast."

President Roosevelt told Henry Morgenthau, "If I should die tomorrow, I want you to know this. I am absolutely convinced that Lindbergh is a Nazi." He wrote to Henry Stimson and claimed that: "When I read Lindbergh's speech, I felt that it could not have been better put if it had been written by Goebbels himself. What a pity that this youngster has completely abandoned his belief in our form of government and has accepted Nazi methods because apparently they are efficient." Roosevelt asked J. Edgar Hoover to keep a watch on him. He willingly did so for he had been upset by Lindbergh's critical comments about the failures of the FBI investigation into the kidnapping and murder of his infant son.

On 16th May 1941, Carter sent Roosevelt a report from a Swedish member of parliament "who has a record of being 60% right ... on all developments since Munich." The informant reported that millions of German troops were massing on the Soviet border, and "maps of Russia were being printed in huge quantities." Carter's source also predicted the invasion toward the end of June. "The Germans are reported confident that they can beat Russia in one or two months."

British intelligence had also received similar information from other sources and Richard Stafford Cripps, Britain's ambassador to Moscow, had held a press conference and declared that Germany would attack Russia before the end of June. The Soviet spy, the German journalist Richard Sorge, cabled his Moscow controllers that the invasion would begin on 22nd June, 1941.

Joseph E. Persico has argued: "The Soviet dictator was convinced that the capitalists would spread any canard to drive a wedge between him and his new ally, Germany. This partnership, he believed would keep his country safe from attack while Hitler went about swallowing up the rest of Europe.... On the night of June 21, a German soldier deserted to the Russian army and told his interrogators that an attack would take place at 3 a.m. the next morning. Within three hours Stalin had the report, but rejected it and supposedly ordered the bearer of the news shot. The invasion that FDR had known about for over five months began when the deserter said it would. Like the husband who is the last to know that his wife is faithless, Stalin was stunned by the invasion. As the depth of Hitler's deceit and his country's debacle sank in, Stalin went into a depression approaching a nervous breakdown."

On this day in 1945 RAF sent 773 Avro Lancasters to bomb Dresden. During the next two days the USAAF sent over 527 heavy bombers to follow up the RAF attack. Dresden was nearly totally destroyed. As a result of the firestorm it was afterwards impossible to count the number of victims. Recent research suggest that 35,000 were killed but some German sources have argued that it was over 100,000.

In 1941 Charles Portal of the British Air Staff advocated that entire cities and towns should be bombed. Portal claimed that this would quickly bring about the collapse of civilian morale in Germany. Air Marshall Arthur Harris agreed and when he became head of RAF Bomber Command in February 1942, he introduced a policy of area bombing (known in Germany as terror bombing) where entire cities and towns were targeted.

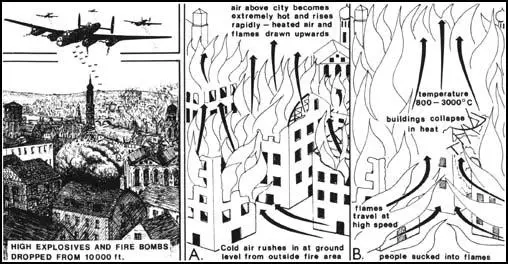

One tactic used by the Royal Air Force and the United States Army Air Force was the creation of firestorms. This was achieved by dropping incendiary bombs, filled with highly combustible chemicals such as magnesium, phosphorus or petroleum jelly (napalm), in clusters over a specific target. After the area caught fire, the air above the bombed area, become extremely hot and rose rapidly. Cold air then rushed in at ground level from the outside and people were sucked into the fire.

In 1945, Arthur Harris decided to create a firestorm in the medieval city of Dresden. He considered it a good target as it had not been attacked during the war and was virtually undefended by anti-aircraft guns. The population of the city was now far greater than the normal 650,000 due to the large numbers of refugees fleeing from the advancing Red Army.

On this day in 1958 Christabel Pankhurst died. Christabel, the eldest daughter of Richard Pankhurst and Emmeline Pankhurst, was born at Drayton Terrace, Old Trafford, Manchester on 22nd September, 1880. Over the next five years Emmeline gave birth to Sylvia Pankhurst (1882), Frank (1884) and Adela Pankhurst (1885). According to her biographer, June Purvis, "Christabel was her mother's favourite".

Christabel's father was a committed socialist and a strong advocate of women's suffrage. Richard had been responsible for drafting an amendment to the Municipal Franchise Act of 1869 that had resulted in unmarried women householders being allowed to vote in local elections. Richard had served on the Married Women's Property Committee (1868-1870) and was the main person responsible for the drafting of the women's property bill that was passed by Parliament in 1870.

Christabel remembers attending a meeting chaired by her father: "Dr Pankhurst, as Chairman, said in his speech that if the suffrage was not given to women the result would be terrible. If a body was half of it bound, how was it to be expected that it would grow and develop properly?" She also copied out articles on "serious subjects" written by her father.

In 1886 the family moved to London where their home in Russell Square became a centre for gatherings of socialists and suffragists. Richard and Emmeline Pankhurst were also both members of the Fabian Society. At a young age, their children were encouraged to attend these meetings. This had a major impact on their political views. "Such experiences had a decisive effect on Christabel. Nothing she learned from the inadequate education offered by governesses or, when the family moved back to the north in 1893, at the high schools she attended - first in Southport and then in Manchester - compared with the political education she received at home."

In 1893 Richard and Emmeline returned to Manchester where they formed a branch of the new Independent Labour Party (ILP). This new party was more supportive of women's rights than older Socialist organizations. The Social Democratic Federation "viewed female aspirations essentially as an expression of bourgeois individualism" and although the Fabian Society "allowed female participation it remained indifferent towards votes for women".

Women were allowed to be candidates to join the Poor Law Board of Guardians. However, because of property qualifications most women were ineligible and only a handful were elected. However, these qualifications were abolished by William Gladstone and his Liberal government in 1894 and later that year, Emmeline, with the support of the ILP, became a candidate for the Chorlton Board of Guardians. "Throwing herself into the new cause" she came top of the poll with 1,276 votes.

In the 1895 General Election, her father stood as the ILP candidate for Gorton, an industrial suburb of the city. Christabel and Sylvia became involved in the campaign. Sylvia later recalled that many of the voters "added they would not vote for him this time, as he had no chance now; but next time he would get in... they seemed to regard the election as a sort of game, in which it was important to vote on the winning side". The Conservative Party candidate received 5,865 votes compared to Pankhurst's 4,261.

In June 1898, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst took a holiday in Europe. While they were in Geneva they received a telegram from Sylvia: "Dr Pankhurst ill. Come immediately." When they stepped off the train in Manchester, they saw newspaper placards announcing his death. Richard Pankhurst had died of a perforated ulcer. The funeral procession to Brookwood Cemetery was accompanied by an ILP deputation. The coffin was borne in an open carriage through streets lined with spectators.

"Faithful and True My Loving Comrade", a quote from Walt Whitman, were the words Emmeline Pankhurst choose for his gravestone. Without her husband's income, Emmeline had to sell their home and move to a cheaper residence at 62 Nelson Street, Manchester. She was also forced to accept the post of registrar of births and deaths in order to increase the family income.

Christabel Pankhurst attended lectures at Manchester University. While there she met Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, who were trying to persuade working class women in Manchester to join the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). The author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued that: "Christabel Pankhurst had formed a close friendship with Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, suffrage campaigners who lived together in Manchester. Her relationship with Eva, in particular, had become intense enough to excite a great deal of comment from her family."

Sylvia Pankhurst also made comments on this relationship: "Eva Gore-Booth had a personality of great charm... Christabel adored her, and when Eva suffered from neuralgia, as often happened, would sit with her for hours massaging her head. To all of us at home this seemed remarkable indeed, for Christabel had never been willing to act the nurse to any other human being. She detested sickness, and even left home when Adela had scarlet fever."

Christabel never had any romantic relationships with men. Martin Pugh has argued: "Christabel had been the kind of girl who was pretty enough to attract young men, but also sufficiently mature and self-possessed to intimidate them. She enjoyed being a leader and professed to consider her male contemporaries as rather foolish." Helena Swanwick recalled: "She seemed to me a lonely person with all her capacity for winning adorers... she was, unlike her sisters, cynical and cold at heart."

On 27th February 1900, representatives of all the socialist groups in Britain (the Independent Labour Party (ILP), the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and the Fabian Society, met with trade union leaders at the Congregational Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street. After a debate the 129 delegates decided to pass the motion proposed by Keir Hardie to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." To make this possible the Conference established a Labour Representation Committee (LRC).

Emmeline Pankhurst hoped the new Labour Party would support votes for women on the same terms as men. Although the party made it clear in its programme it favoured equal rights for men and women. Keir Hardie argued for "the vote for women on the same terms as it is or may be granted to men". However, others in the party, including Isabella Ford, thought that as large number of working-class males did not have the vote, they should be demanding "full adult suffrage". Philip Snowden pointed out that if only middle-class women got the vote it would favour the Conservative Party. This was also the view of left-wing members of the Liberal Party such as David Lloyd George.

In the 1902 Labour Party conference Emmeline Pankhurst created controversy when she proposed that "in order to improve the economic and social condition of women, it is necessary to take immediate steps to secure the granting of the suffrage to women on the same terms as it is, or may be, granted to men". This was not accepted and instead a resolution calling for "adult suffrage" became party policy.

Pankhurst's views on limited suffrage received a great deal of criticism. One of its leaders, John Bruce Glasier, had been a long-term supporter of universal suffrage, and like his wife, Katharine Glasier, was particularly opposed to Pankhurst's views. He recorded in his diary that he disapproved of her "individualist sexism". At a meeting with Emmeline and her daughter, Christabel Pankhurst, he claimed that the two women "were not seeking democratic freedom, but self-importance". Trade union leader, Henry Snell, agreed: "Mrs. Pankhurst was magnetic, courageous, audacious, and resolute. Mrs. Pankhurst was an autocrat masquerading as a democrat".

After her defeat at conference, Emmeline Pankhurst decided to leave the Labour Party and decided to establish the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Emmeline stated that the main aim of the organisation was to recruit working class women into the struggle for the vote. "We resolved to limit our membership exclusively to women, to keep ourselves absolutely free from ant party affiliation, and to be satisfied with nothing but action on our question. Deeds, not words, was to be our permanent motto."

The main objective was to gain, not universal suffrage, the vote for all women and men over a certain age, but votes for women, “on the same basis as men.” This meant winning the vote not for all women but for only the small stratum of women who could meet the property qualification. As one critic suggested, it was "not votes for women", but “votes for ladies.” As an early member of the WSPU, Dora Montefiore, pointed out: "The work of the Women’s Social and Political Union was begun by Mrs. Pankhurst in Manchester, and by a group of women in London who had revolted against the inertia and conventionalism which seemed to have fastened upon... the NUWSS."

The forming of the WSPU upset both the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and the Labour Party, the only party at the time that supported universal suffrage. They pointed out that in 1903 only a third of men had the vote in parliamentary elections. On the 16th December 1904, The Clarion published a letter from Ada Nield Chew, a leading figure in the Independent Labour Party, attacking WSPU policy: "The entire class of wealthy women would be enfranchised, that the great body of working women, married or single, would be voteless still, and that to give wealthy women a vote would mean that they, voting naturally in their own interests, would help to swamp the vote of the enlightened working man, who is trying to get Labour men into Parliament."

The following month Christabel Pankhurst replied to the points that Ada Nield Chew made: "Some of us are not at all so confident as is Mrs Chew of the average middle class man's anxiety to confer votes upon his female relatives." A week later Ada Nield Chew retorted that she still rejected the policies in favour of "the abolition of all existing anomalies... which would enable a man or woman to vote simply because they are man or woman, not because they are more fortunate financially than their fellow men and women".

As the authors of One Hand Tied Behind Us (1978) pointed out: "The fiery exchange ran on through the spring and into March. The two women both relished confrontation, and neither was prepared to concede an inch. They had no sympathy for the other's views, and shared no common experiences that might help to bridge the chasm... Christabel, daughter of a barrister... had little personal experience of working women's lives. Ada Nield Chew had known little else... her life had been a series of battles against women's low wages and appalling working conditions."

The WSPU was often accused of being an organisation that existed to serve the middle and upper classes. As Annie Kenney was one of the organizations few working class members, when the WSPU decided to open a branch in the East End of London, she was asked to leave the mill and become a full-time worker for the organisation. Annie joined Sylvia Pankhurst in London in an attempt to persuade working-class women to join the WSPU.

By 1905 the media had lost interest in the struggle for women's rights. Newspapers rarely reported meetings and usually refused to publish articles and letters written by supporters of women's suffrage. In 1905 the WSPU decided to use different methods to obtain the publicity they thought would be needed in order to obtain the vote. It seemed certain that the Liberal Party would form the next government. Therefore, the WSPU decided to target leading figures in the party.

On 13th October 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were both arrested.

Christabel Pankhurst was charged with assaulting the police and Annie Kenney with obstruction. In a deliberately aggressive courtroom speech, Christabel admitted that she has assaulted police officers and pointed out that "I am only sorry that one of them was not Sir Edward Grey... We cannot make any orderly protest because we have not the means whereby citizens may do such a thing: we have not a vote, and so long as we have not a vote we must be disorderly... When we have that, this will not see us in the police courts; but so long as we have not votes this will happen."

The following month Christabel Pankhurst replied to the points that Ada Nield Chew made: "Some of us are not at all so confident as is Mrs Chew of the average middle class man's anxiety to confer votes upon his female relatives." A week later Ada Nield Chew retorted that she still rejected the policies in favour of "the abolition of all existing anomalies... which would enable a man or woman to vote simply because they are man or woman, not because they are more fortunate financially than their fellow men and women".

As the authors of One Hand Tied Behind Us (1978) pointed out: "The fiery exchange ran on through the spring and into March. The two women both relished confrontation, and neither was prepared to concede an inch. They had no sympathy for the other's views, and shared no common experiences that might help to bridge the chasm... Christabel, daughter of a barrister... had little personal experience of working women's lives. Ada Nield Chew had known little else... her life had been a series of battles against women's low wages and appalling working conditions."

The WSPU was often accused of being an organisation that existed to serve the middle and upper classes. As Annie Kenney was one of the organizations few working class members, when the WSPU decided to open a branch in the East End of London, she was asked to leave the mill and become a full-time worker for the organisation. Annie joined Sylvia Pankhurst in London in an attempt to persuade working-class women to join the WSPU.

By 1905 the media had lost interest in the struggle for women's rights. Newspapers rarely reported meetings and usually refused to publish articles and letters written by supporters of women's suffrage. In 1905 the WSPU decided to use different methods to obtain the publicity they thought would be needed in order to obtain the vote. It seemed certain that the Liberal Party would form the next government. Therefore, the WSPU decided to target leading figures in the party.

On 13th October 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were both arrested.

Christabel Pankhurst was charged with assaulting the police and Annie Kenney with obstruction. In a deliberately aggressive courtroom speech, Christabel admitted that she has assaulted police officers and pointed out that "I am only sorry that one of them was not Sir Edward Grey... We cannot make any orderly protest because we have not the means whereby citizens may do such a thing: we have not a vote, and so long as we have not a vote we must be disorderly... When we have that, this will not see us in the police courts; but so long as we have not votes this will happen."

Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney were both found guilty. Pankhurst was fined ten shillings or a jail sentence of one week. Kenney was fined five shillings, with an alternative of three days in prison. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison. The case shocked the nation. For the first time in Britain women had used violence in an attempt to win the vote.

Emmeline Pankhurst was very pleased with the publicity achieved by the two women. "The comments of the press were almost unanimously bitter. Ignoring the perfectly well-established fact that men in every political meeting ask questions and demand answers of the speakers, the newspapers treated the action of the two girls as something quite unprecedented and outrageous... Newspapers which had heretofore ignored the whole subject now hinted that while they had formerly been in favour of women's suffrage, they could no longer countenance it."

In her autobiography, Annie Kenney described what it was like to be in prison with Christabel: "Being my first visit to jail, the newness of the life numbed me. I do remember the plank bed, the skilly, the prison clothes. I also remember going to church and sitting next to Christabel, who looked very coy and pretty in her prison cap ... I scarcely ate anything all the time I was in prison, and Christabel told me later that she was glad when she saw the back of me, it worried her to see me looking pale and vacant.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence argued that Kenney was a devoted follower of Christabel Pankhurst. "Annie's... devotion took the form of unquestioning faith and absolute obedience ... Just as no ordinary Christian can find that perfect freedom in complete surrender, so no ordinary individual could have given what Annie gave - the surrender of her whole personality to Christabel." Annie admitted that: "For the first few years the militant movement was more like a religious revival than a political movement. It stirred the emotions, it aroused passions, it awakened the human chord which responds to the battle-call of freedom ... the one thing demanded was loyalty to policy and unselfish devotion to the cause."

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued that Annie Kenney had a series of romantic attachments with other suffragettes: "The relationship (with Christabel Pankhurst) would be mirrored, though never matched in its intensity, by a number of later relationships between Annie and other suffragettes. The extent of their physical nature has never been revealed, but it is certain that in some sense these were romantic attachments". According to Sylvia Pankhurst, Christabel had a series of intimate relationships with women including Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth. Her relationship with Eva, in particular, had become intense enough to excite a great deal of comment from her family.

In the 1906 General Election the Liberal Party won 399 seats and gave them a large majority over the Conservative Party (156) and the Labour Party (29). Pankhurst hoped that Henry Campbell-Bannerman, the new prime minister, and his Liberal government, would give women the vote. However, several Liberal MPs were strongly against this. It was pointed out that there were a million more adult women than men in Britain. It was suggested that women would vote not as citizens but as women and would "swamp men with their votes".

Campbell-Bannerman gave his personal support to Emmeline Pankhurst and Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), though he warned them that he could not persuade his colleagues to support the legislation that would make their aspiration a reality. Despite the unwillingness of the Liberal government to introduce legislation, Fawcett remained committed to the use of constitutional methods to gain votes for women. However, Christabel Pankhurst took a very different view.

It has been estimated that over 400 members of parliament, belonging to all parties, were pledged to the principle of women's suffrage. Private members' bills were introduced, but without Government help they made no headway. According to John Grigg: "Christabel Pankhurst... dominated all around her, including her remarkable mother, and the tactics of W.S.P.U. militancy were pre-eminently hers... In her view the lobbying of backbenchers was a complete waste of time. She had a twofold aim - to make the Government's life a misery, and to capture the imagination of the people." Christabel's tactics was to target those members of the government, like David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill, on the left of the Liberal Party, who had made statements in favour of women having the vote as she regarded them as "traitors and backsliders for not insisting upon the introduction of a franchise bill under threat of resignation."

In April 1907 Mary Sheepshanks, the vice-principal of Morley College for Working Men and Women, invited Christabel Pankhurst to speak in a debate on women's suffrage. During the debate she argued: "We are absolutely determined to have our way, and to have our say in the government of affairs. We are going to develop on our own lines and listen to the pleadings of our inner nature. We shall think our own thoughts and strengthen our own intelligence. We want the abolition of sex in the choice of legislative power as well as privilege. For the present we want the woman to have what the men have."

Christabel obtained a first-class law degree in 1907 but her gender prevented her from developing a career as a barrister. Christabel decided to leave Manchester and join the suffragette campaign in London where she lived in the home of Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. Christabel was appointed as the WSPU's chief organizer on a salary of £2 10s. per week. Lady Constance Lytton who met her at this time commented on her "wonderful character" and her "brilliant intellect".

Christabel disagreed with the way the campaign was being run. The initial strategy of the WSPU had been to recruit the support of working class women. Christabel advocated a campaign that would appeal to the more prosperous members of society. Whereas Sylvia Pankhurst and Charlotte Despard argued for the vote for all adults, Christabel favoured limited suffrage, a system that would only give the vote to women with money and property. Christabel pointed out that the WSPU relied heavily on the money supplied by wealthy women.

Emmeline Pankhurst supported her daughter in this stance but it was opposed by two of her daughters, Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst, who were both socialists and believed in universal suffrage rather than a limited franchise that favoured middle-class women. In September 1907 both Christabel and Emmeline resigned their membership of the Independent Labour Party, who had been arguing that votes for women on the same terms as men would only enfranchise middle-class women who would probably vote for the Conservative Party.

In 1907 some leading members of the Women's Social and Political Union began to question the leadership of Christabel and Emmeline Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were having too much influence over the organisation. In the autumn of 1907, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL).

On 25th June 1909, Marion Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. On 5th July, 1909 she petitioned the governor of Holloway Prison: “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.”

Christabel Pankhurst later claimed that this strategy had not been agreed by the organisation: "Miss Wallace Dunlop, taking counsel with no one and acting entirely on her own initiative, sent to the Home Secretary, Mr. Gladstone, as soon as she entered Holloway Prison, an application to be placed in the first division as befitted one charged with a political offence. She announced that she would eat no food until this right was conceded."

Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. When the doctor asked her what she was going to eat, she replied: "My determination". He answered: "Indigestible stuff, but tough no doubt." Herbert Gladstone, the Home Secretary, was consulted and he told the governor of the prison that "she should be allowed to die."

However, on reflection, they thought that if this happened, Dunlop might become a martyr and after ninety-one hours she was suddenly set free. According to Joseph Lennon: "She came to her prison cell as a militant suffragette, but also as a talented artist intent on challenging contemporary images of women. After she had fasted for ninety-one hours in London’s Holloway Prison, the Home Office ordered her unconditional release on July 8, 1909, as her health, already weak, began to fail".

On 22nd September 1909, Charlotte Marsh, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Leigh were arrested while disrupting a public meeting being held by Herbert Asquith. Marsh, Ainsworth and Leigh were all sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force.

Keir Hardie, the Labour MP, protested against the idea of force-feeding in the House of Commons. However, his comments were greeted with a chorus of laughter and jeers. One newspaper reported: "Most of us desire something or other which we have not got... but we do not therefore take hatchets and wreck people's houses, or even shriek hysterically because the whole course of government and society is not altered to give us what we seek. These notoriety-hunters have effectually discredited the movement they think to promote."

The authorities believed that force-feeding would act as a deterrent as well as a punishment. This was a serious miscalculation and in many ways it had the opposite effect. Militant members of the WSPU now had beliefs as strong as any religion and now they could argue that women were actually being tortured for their faith. "Suffragettes submitted to force-feeding as a way to express solidarity with their friends as well as to further the cause."

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, one of the early hunger-strikers pointed out that if the government was so naive as to think "the nasal tube or the stomach pump, the steel gag, the punishment cell, handcuffs and the straight jacket would break the spirit of women who were determined to win the enfranchisement of their sex, they were again woefully misled". The WSPU did get the support of two prominent journalists, Henry N. Brailsford and Henry Nevinson, who both resigned from The Daily News in protest against its refusal to condemn forcible feeding.

Christabel Pankhurst now used the WSPU newspaper, Votes for Women, to advocate the hunger-strike. "The spiritual force which they are exerting is so great that prison walls are rent, prison gates forced open, and they emerge free in body as they have never for an instant ceased to be.... Those who, in these latter days, are privileged to witness this triumph of the spiritual over the physical, understand the true meaning and manner of the miracles of old times."

Christabel was also responsible for persuading 116 doctors to sign a letter sent to Henry Asquith, the new prime minister, protesting against artificial feeding. "We submit to you, that this method of feeding when the patient resists is attending with the gravest risks, that unforeseen accidents are liable to occur, and that the subsequent health of the person may be seriously injured. In our opinion this action is unwise and inhumane. We therefore beg that you will interfere to prevent the continuance of this practice."

On 8th October, 1909, Christabel had a meeting with leading militants, Constance Lytton, Jane Brailsford, Emily Wilding Davison, Annie Kenney and Kitty Marion. who resolved to undertake acts of violence in order to protest against forcible feeding. "There were twelve women... all intending stone-throwers, and Christabel was there to hearten us up and go into details about the way in which we were to do it."

On 9th November 1909, Lady Lytton, was arrested in Newcastle. She was sent to prison for 30 days. "Mrs. Brailsford, who had struck at the barricade with an axe, was also given the option of being bound over, which she, of course, refused, with the alternative of a month's imprisonment in the second division. We were put again into a van, but had only a short way to drive. We were shown into a passage of the prison where the Governor came and spoke to us. He was very civil, and begged us not to go on the hunger-strike." She did but as she pointed out in Prisons and Prisoners (1914) after a couple of days "the wardress came in and announced that I was released, because of the state of my heart!"

Herbert Gladstone, who was in fact a supporter of votes for women, refused to back-down over forced-feeding. "My duty is unpleasant and distasteful enough, but that is no reason why I should shirk it. I admire the gallantry of many of these girls as strongly as I detest the unscrupulous use use which is being made of their qualities by older women who should know better. Women's franchise will come, but it will come not through violent actions and not through sentimental or cowardly surrender to them."

Christabel Pankhurst made it clear that the WSPU would not change their tactics and members in prison would continue to go on hunger-strike. "They (members of the Liberal government) shall not have peace. We have at last got up steam and tasted the joy of battle. Our blood is up... the more they ask for quarter the less they shall get. We will not betray the women in prison... For the weak to use their little strength against the huge forces of tyranny is divine." However, Christabel made sure she was not arrested during this period as she did not want to "undergo forcible feeding" and "intended to postpone this distasteful eventually for as long as possible".

In January 1910, Herbert Asquith called a general election in order to obtain a new mandate. However, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Henry Brailsford, a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage wrote to Millicent Fawcett, suggesting that he should attempt to establish a Conciliation Committee for Women's Suffrage. "My idea is that it should undertake the necessary diplomatic work of promoting an early settlement".

Emmeline Pankhurst and Millicent Fawcett both agreed to the idea and the WSPU declared a truce in which all militant activities would cease until the fate of the Conciliation Bill was clear. A Conciliation Committee, composed of 36 MPs (25 Liberals, 17 Conservatives, 6 Labour and 6 Irish Nationalists) all in favour of some sort of women's enfranchisement, was formed and drafted a Bill which would have enfranchised only a million women but which would, they hoped, gain the support of all but the most dedicated anti-suffragists. Fawcett wrote that "personally many suffragists would prefer a less restricted measure, but the immense importance and gain to our movement is getting the most effective of all the existing franchises thrown upon to woman cannot be exaggerated."

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. However, before they completed the task, Asquith called another election in order to get a clear majority. However, the result was very similar and Asquith still had to rely on the support of the Labour Party to govern the country.

A new Conciliation Bill was passed by the House of Commons on 5th May 1911 with a majority of 167. The main opposition came from Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, who saw it as being "anti-democratic". He argued "Of the 18,000 women voters it is calculated that 90,000 are working women, earning their living. What about the other half? The basic principle of the Bill is to deny votes to those who are upon the whole the best of their sex. We are asked by the Bill to defend the proposition that a spinster of means living in the interest of man-made capital is to have a vote, and the working man's wife is to be denied a vote even if she is a wage-earner and a wife."

David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was officially in favour of woman's suffrage. However, he had told his close associates, such as Charles Masterman, the Liberal MP in West Ham North: "He (David Lloyd George) was very much disturbed about the Conciliation Bill, of which he highly disapproved although he is a universal suffragist... We had promised a week (or more) for its full discussion. Again and again he cursed that promise. He could not see how we could get out of it, yet he regarded it as fatal (if passed)."

Lloyd George was convinced that the chief effect of the Bill, if it became law, would be to hand more votes to the Conservative Party. During the debate on the Conciliation Bill he stated that justice and political necessity argued against enfranchising women of property but denying the vote to the working class. The following day Herbert Asquith announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise the four million men currently excluded from voting and suggested it could be amended to include women. Paul Foot has pointed out that as the Tories were against universal suffrage, the new Bill "smashed the fragile alliance between pro-suffrage Liberals and Tories that had been built on the Conciliation Bill."

Millicent Fawcett still believed in the good faith of the Asquith government. However, the WSPU, reacted very differently: "Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst had invested a good deal of capital in the Conciliation Bill and had prepared themselves for the triumph which a women-only bill would entail. A general reform bill would have deprived them of some, at least, of the glory, for even though it seemed likely to give the vote to far more women, this was incidental to its main purpose."

Christabel Pankhurst wrote in Votes for Women that Lloyd George's proposal to give votes to seven million instead of one million women was, she said, intended "not, as he professes, to secure to women a larger measure of enfranchisement but to prevent women from having the vote at all" because it would be impossible to get the legislation passed by Parliament.

On 21st November, the WSPU carried out an "official" window smash along Whitehall and Fleet Street. This involved the offices of the Daily Mail and the Daily News and the official residences or homes of leading Liberal politicians, Herbert Asquith, David Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, Edward Grey, John Burns and Lewis Harcourt. It was reported that "160 suffragettes were arrested, but all except those charged with window-breaking or assault were discharged."

The following month Millicent Fawcett wrote to her sister, Elizabeth Garrett: "We have the best chance of Women's Suffrage next session that we have ever had, by far, if it is not destroyed by disgusting masses of people by revolutionary violence." Elizabeth agreed and replied: "I am quite with you about the WSPU. I think they are quite wrong. I wrote to Miss Pankhurst... I have now told her I can go no more with them."

Henry Brailsford went to see Emmeline Pankhurst and asked her to control her members in order to get the legislation passed by Parliament. She replied "I wish I had never heard of that abominable Conciliation Bill!" and Christabel Pankhurst called for more militant actions. The Conciliation Bill was debated in March 1912, and was defeated by 14 votes. Asquith claimed that the reason why his government did not back the issue was because they were committed to a full franchise reform bill. However, he never kept his promise and a new bill never appeared before Parliament.

Some members of the WSPU, including Adela Pankhurst became concerned about the increase in the violence as a strategy. She later told fellow member, Helen Fraser: "I knew all too well that after 1910 we were rapidly losing ground. I even tried to tell Christabel this was the case, but unfortunately she took it amiss." After arguing with Emmeline Pankhurst about this issue she left the WSPU in October 1911. Sylvia Pankhurst was also critical of this new militancy.

In 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence both disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored their objections. As soon as this wholesale smashing of shop windows began, the government ordered the arrest of the leaders of the WSPU. Christabel escaped to France but Frederick and Emmeline were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. They were also successfully sued for the cost of the damage caused by the WSPU.

Emmeline Pankhurst was one of those arrested. Once again she went on hunger strike: "I generally suffer most on the second day. After that there is no very desperate craving for food. weakness and mental depression take its place. Great disturbances of digestion divert the desire for food to a longing for relief from pain. Often there is intense headache, with fits of dizziness, or slight delirium. Complete exhaustion and a feeling of isolation from earth mark the final stages of the ordeal. Recovery is often protracted, and entire recovery of normal health is sometimes discouragingly slow." After she was released from prison she was nursed by Catherine Pine.

Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes.