On this day on 13th December

On this day in 1577 Sir Francis Drake sets sail from Plymouth, England, on his round-the-world voyage. Drake was introduced to Sir Francis Walsingham, and this association led to a plan for Drake to take a fleet into the Pacific and raid Spanish settlements there. Investors included Walsingham, Elizabeth I, Christopher Hatton and John Hawkins. Drake's ship was the 150 ton Pelican (renamed the Golden Hinde half-way through the journey) double-planked, lead-sheathed, and armed with 18 guns. Wynter contributed his own 80 ton Elizabeth, which carried 11 guns. Another 12 guns were distributed among the 50 ton Marigold, the 30 ton Swan, and the 15 ton Benedict.

The journey began on 13th December 1577. By the end of the month six Spanish and Portuguese ships were taken, then looted and eventually set free. Drake also abandoned the Benedict and took one of the Spanish vessels, which was renamed Christopher. The following month they captured a Portuguese merchant vessel, Santa Maria. The commander was Nuño de Silva, who knew the coast of South America. Drake took Silva to serve as pilot of his own fleet.

In June 1578 the fleet arrived at Puerto San Julián, on the southern coast of Argentina, where Drake put Thomas Doughty on trial for mutiny. He was beheaded on 2nd July 1578. Drake feared that others would rebel and so he called the captains and crew together, then announced that all the officers, who held their appointments from the owners of the ships, were relieved of command. He then reappointed them or most of them as officers responsible only to him.

When Drake finally led his fleet through the strait and into the Pacific Ocean, Captain John Wynter took advantage of a storm to leave Drake and took his ship back to England. The Marigold, commanded by Doughty's friend John Thomas, also disappeared, and the Mary was abandoned at Puerto San Julián. Drake, who was left with only the Pelican, renamed it The Golden Hind. Drake now sailed up the Pacific coast. At Valparaíso he took a ship carrying 200,000 pesos in gold, then went ashore and raided the church and the warehouses.

On 5th February 1579 he arrived at Arica on the north coast of Chile and captured a merchant ship carrying thirty or forty bars of silver. As a result of deaths in battles and sickness, Drake's crew to little more than seventy men. Only thirty of them were fit to fight, but that was enough, since the merchant ships Drake took were unarmed. On 1st March he captured the richest ship of all, Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, carrying valuable cargo and 362,000 pesos in silver and gold.

Sailing along the coast of Mexico, Drake took a few more ships and raided several more ports. However, The Golden Hinde was leaking badly and needed to be careened. On 17th June 1579 Drake landed in a bay on the the coast of California. According to Drake's biographer, Harry Kelsey: "Sixteenth-century accounts and maps can be interpreted to show that he stopped anywhere between the southern tip of Baja California and latitude 48° N." Most historians believe that Drake had stopped in a bay on the Point Reyes peninsula (now known as Drake's Bay).

Father Francis Fletcher, the chaplin to the expedition, later wrote in The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake (1628): "Drake's ship entered a convenient and fit harbour." Drake has been reported as saying: "By God's Will we hath been sent into this fair and good bay. Let us all, with one consent, both high and low, magnify and praise our most gracious and merciful God for his infinite and unspeakable goodness toward us. By God's faith hath we endured such great storms and such hardships as we have seen in these uncharted seas. To be delivered here of His safekeeping, I protest we are not worthy of such mercy."

Francis Drake's cousin, John Drake, argued that "Drake... landed and built huts and remained a month and a half, caulking his vessel. The victuals they found were mussels and sea-lions." A local group of Miwok brought him a present of a bunch of feathers and tobacco leaves in a basket. John Sugden, the author of Sir Francis Drake (1990) has argued: "It appeared to the English that the Indians regarded them as gods; they were impervious to English attempts to explain who they were, but at least they remained friendly, and when they had received clothing and other gifts the natives returned happily and noisily to their village." John Drake claims that when they "saw the Englishmen they wept and scratched their faces with their nails until they drew blood, as though this was an act of homage or adoration."

Francis Fletcher suggests that the local people "dispersed themselves into the country, to make known the news." On 26th June a large group of Miwok arrived at Drake's camp. The chief, wearing a head-dress and a skin cape, was followed by painted warriors, each one of whom bore a gift. At the rear of the cavalcade were women and children. A man holding a sceptre of black wood and wearing a chain of clam shells, stepped forward and made a thirty minute speech. While this was going on the women indulged in a strange ritual of self-mutilation that included scratching their faces until the blood flowed. Robert F. Heizer has argued in Elizabethan California (1974) that self-mutilation is associated with mourning and that the Miwok probably thought the British sailors were spirits returning from the dead. However, Drake took the view that they were proclaiming him king of the Miwok tribe.

John Drake pointed out in a statement he made in 1582: "During that time (June, 1579) many Indians came there and when they saw the Englishmen they wept and scratched their faces with their nails until they drew blood, as though this was an act of homage or adoration. By signs Captain Francis Drake told them not to do that, for the Englishmen were not God. These people were peaceful and did no harm to the English, but gave them no food. They are of the colour of the Indians here and are comely. They carry bows and arrows and go naked. The climate is temperate, more cold than hot. To all appearance it is a very good country."

Drake now claimed the land for Queen Elizabeth. He named it Nova Albion "in respect of the white banks and cliffs, which lie towards the sea". Apparently, the cliffs of Point Reyes reminded Drake of the coast at Dover. Drake had a post set up with a plate bearing his name and the date of arriving in California.

When the Golden Hinde left on 23rd July, the Miwok exhibited great distress and ran to the hill-tops to keep the ship in sight for as long as possible. Drake later wrote that during his time in California, "not withstanding it was the height of summer, we were continually visited with nipping cold, neither could we at any time within a fourteen day period find the air so clear as to be able to take height the sun or stars."

Francis Drake then sailed along the California coast but failed to see the Golden Gate and San Francisco bay beyond. This is probably because the area is often shrouded in fog during the summer. The heat in the California Central Valley causes the air there to rise. This can create strong winds which pull cool moist air in from over the ocean through the break in the hills, causing a stream of dense fog to enter the bay.

At Java Drake and his crew loaded plenty of food they sailed through the Indian Ocean, and around the Cape of Good Hope. The provisions lasted until 20 July 1580 when they reached Sierra Leone on the African coast. When Drake arrived in Plymouth on 26th September 1580, he became the first Englishman to circumnavigate the world. Drake return to England as a very wealthy man and he was able to purchase the Buckland Abbey estate. In 1581 Queen Elizabeth knighted Drake and later that year he was elected to the House of Commons.

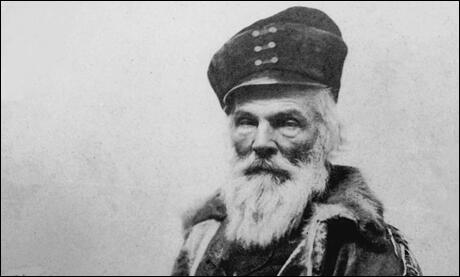

On this day in 1798 American explorer Joseph Walker was born. Walker moved to Missouri in 1818 and two years later was involved in taking trade goods to Santa Fe. He was imprisoned by the Spanish authorities in New Mexico but was released to help fight against the Pawnees.

Walker returned home to Missouri and in 1827 he was elected the first sheriff of Jackson County. He served two terms but eventually left because of the low pay. Walker was involved in buying and selling horses until he was recruited by Captain Benjamin Bonneville as field commander of an expedition to the West. Bonneville's party spent two seasons trapping beavers on the Salmon River.

In 1833 Bonneville suggested to Walker that he should take a party of men to California. The beaver appeared to be decline in the Rocky Mountains and it was thought that new trapping opportunities would be found in this unexplored territory.

Walker and his party of forty men left Green River on 20th August, 1833. Each man took four horses. One to ride and three to carry supplies. This included 60 pounds of dried meat per man. When he reached Salt Lake he met with local Bannock Indians to discover the best route west. After these consultations Walker decided to follow the Humboldt River into Nevada. In September, 1833, around 800 Digger Indians surrounded Walker's party. They had never seen guns before and after 39 had been killed they decided to retreat.

Soon afterwards they reached the Sierra Nevada mountains. The climb was difficult and with a shortage of food, several men argued that they should be allowed to go back. Walker insisted that they should continue and after killing and eating some of the horses, they came out of the Sierra after three weeks. Soon afterwards they became the first Americans to explore the Yosemite Valley.

While in California Walker and his men experienced their first earthquake. They also discovered the giant redwood trees. At the end of November the party reached the coast and saw the Pacific for the first time. Walker now headed southward toward Monterey. They were well received by the Spaniards and they spent the next three months building up their strength. Six of the party enjoyed it so much that they got permission from Walker to stay in California.

The Spanish authorities offered Walker a 50 square-mile tract of land if he agreed to stay on and bring in fifty families to settle in Monterey. Walker refused the offer and on 14th February, 1834, Walker's party headed east. At the base of the Sierra he turned south in search of a easier crossing than the one he used on the westward trip. He found it and it was later named the Walker Pass.

Once again the Nevada desert caused the party problems. They ran out of water and a large number of animals died of thirst. To survive the men were forced to drink the blood of these dead animals. In the Humboldt Sink the Diggers once again attacked Walker's party. A battle took place in June and 14 Diggers were killed. The party, without the loss of any men during the journey, arrived at Bear River on 12th July, 1834. One of the members, Zenas Leonard, wrote that the government should take control of California as soon as possible: "for we have good reason to suppose that the territory west of the mountain will some day be equally as important to a nation as that on the east."

In 1835 Joseph Walker became brigade leader of the American Fur Company. However, with the decline in the fur trade, Walker became involved in horse and mule trading trips. He also guided wagon trains to California and explored the Mono Lake area. Joseph Walker died on his Contra Costa County ranch in California on 13th November, 1872.

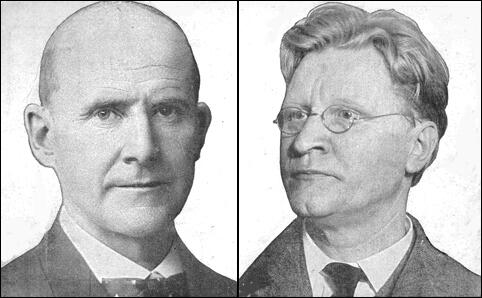

On this day in 1864 progressive politician Emil Seidel was born in Pennsylvania. Seidel was born in Ashland, Pennsylvania on 13th December, 1864. His family moved to Wisconsin when he was a child. As a young man he lived in Germany where he trained as a woodcarver.

While in Germany he became a socialist and when he returned to the United States he joined the Socialist Party of America. He settled in Milwaukee and in 1904 Seidel and eight other socialists were elected as city aldermen.

In 1910, the Socialist Party in Milwaukee decided to put up Seidel as their candidate for mayor. With the support of Victor Berger and his newspaper, the Milwaukee Leader, and the city's large German-born population, Seidel became the first socialist mayor of a major city in the United States. One of Seidel's achievements was to introduce the country's first worker's compensation program in 1911. Other initiatives included adult and worker education classes and free medical and dental examinations for schoolchildren.

The supporters of the Democratic Party and the Republican Party joined forces to defeat Seidel in 1912. Later that year the Socialist Party nominated Eugene Debs and Seidel as their presidential and vice presidential candidates. Woodrow Wilson won the election but they received the respectable total of 897,011 votes. Emil Seidel, who was also alderman in 1916-20 and 1932-36, died on 24th June, 1947.

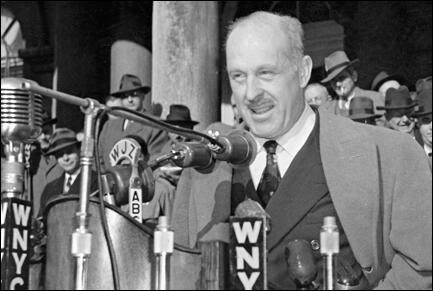

On this day in 1897 Drew Pearson, was born in Evanston, Illinois. In 1902 the family moved to Pennsylvania, where his father, Paul Pearson, became professor of public speaking at Swarthmore College. Pearson was educated at the Phillips Exeter Academy and Swarthmore College, where he edited the student newspaper, The Phoenix. In 1919 Pearson, a Quaker, travelled to Serbia where he spent two years rebuilding houses that had been destroyed during the First World War.

After returning to America, Drew taught industrial geography at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1923 he embarked on a worldwide tour visiting Japan, China, Australia, New Zealand and India. He paid for his trip by writing articles for an American newspaper syndicate. Pearson taught briefly at Columbia University before returning to journalism and reporting on anti-foreigner demonstrations in China (1927), the Geneva Naval Conference (1928) and the Pan American Conference in Cuba (1928). In 1929 Pearson became Washington correspondent of the Baltimore Sun. Three years later he joined the Scripps-Howard syndicate, United Features. His Merry-Go-Round column was published in newspapers all over the United States.

Pearson was a strong supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal program. He also upset more conservative editors when he advocated United States involvement in the struggle against fascism in Europe. Pearson's articles were often censored and so in 1941 he switched to the more liberal The Washington Post.

Pearson was a close friend of Ernest Cuneo, a senior figure in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Cuneo leaked several stories to Pearson including one concerning General George S. Patton. On 3rd August 1943, he visited the 15th Evacuation Hospital where he encountered Private Charles H. Kuhl, who had been admitted suffering from shellshock. When Patton asked him why he had been admitted, Kuhl told him "I guess I can't take it." According to one eyewitness Patton "slapped his face with a glove, raised him to his feet by the collar of his shirt and pushed him out of the tent with a kick in the rear." Kuhl was later to claim that he thought Patton, as well as himself, was suffering from combat fatigue.

Two days after the incident he sent a memo to all commanders in the 7th Army: "It has come to my attention that a very small number of soldiers are going to the hospital on the pretext that they are nervously incapable of combat. Such men are cowards and bring discredit on the army and disgrace to their comrades, whom they heartlessly leave to endure the dangers of battle while they, themselves, use the hospital as a means of escape. You will take measures to see that such cases are not sent to the hospital but are dealt with in their units. Those who are not willing to fight will be tried by court-martial for cowardice in the face of the enemy."

On 10th August 1943, Patton visited the 93rd Evacuation Hospital to see if there were any soldiers claiming to be suffering from combat fatigue. He found Private Paul G. Bennett, an artilleryman with the 13th Field Artillery Brigade. When asked what the problem was, Bennett replied, "It's my nerves, I can't stand the shelling anymore." Patton exploded: "Your nerves. Hell, you are just a goddamned coward, you yellow son of a bitch. Shut up that goddamned crying. I won't have these brave men here who have been shot seeing a yellow bastard sitting here crying. You're a disgrace to the Army and you're going back to the front to fight, although that's too good for you. You ought to be lined up against a wall and shot. In fact, I ought to shoot you myself right now, God damn you!" With this Patton pulled his pistol from its holster and waved it in front of Bennett's face. After putting his pistol way he hit the man twice in the head with his fist. The hospital commander, Colonel Donald E. Currier, then intervened and got in between the two men.

Colonel Richard T. Arnest, the man's doctor, sent a report of the incident to General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The story was also passed to the four newsmen attached to the Seventh Army. Although Patton had committed a court-martial offence by striking an enlisted man, the reporters agreed not to publish the story. Quentin Reynolds of Collier's Weekly agreed to keep quiet but argued that there were "at least 50,000 American soldiers on Sicily who would shoot Patton if they had the chance."

Eisenhower now had a meeting with the war correspondents who knew about the incident and told them that he hoped they would keep the "matter quiet in the interests of retaining a commander whose leadership he considered vital." Ernest Cuneo, who was fully aware, now decided to pass this story to Pearson and in November 1943, he told the story on his weekly syndicated radio program. Some politicians demanded that George S. Patton should be sacked but General George Marshall and Henry L. Stimson supported Eisenhower in the way he had dealt with the case.

During the Second World War Pearson created a great deal of controversy when he took up the case of John Gates, a member of the American Communist Party, who was not allowed to take part in the D-Day landings. Gates later pointed out: "Newspaper columnist Drew Pearson published an account of my case... Syndicated coast-to-coast, the column meant well but it contained all kinds of unauthorized, secret military information - the name of my battalion, the fact that it had been alerted for overseas, my letter to the President and his reply, and the officers' affidavits. As a result of this violation of military secrecy, the date for the outfit going overseas was postponed, the order restoring me to my battalion was countermanded and I was out of it for good. It seems that some of my friends, a bit overzealous in my cause, had given Pearson all this information, thinking the publicity would do me good."

Pearson also became a radio broadcaster. He soon became one of America's most popular radio personalities. After the war he was an enthusiastic supporter of the United Nations and helped to organize the Friendship Train project in 1947. The train travelled coast-to-coast collecting gifts of food for those people in Europe still suffering from the consequences of the war.

In 1947 Drew Pearson recruited Jack Anderson as his assistant. Over the next few years Anderson was able to use his contacts that he had developed in the Office of Strategic Services(OSS) in China during the Second World War. This included John K. Singlaub, Ray S. Cline, Richard Helms, E. Howard Hunt, Mitchell WerBell, Paul Helliwell, Robert Emmett Johnson and Lucien Conein. Others working in China at that time included Tommy Corcoran, Whiting Willauer and William Pawley.

One of Anderson's first stories concerned the dispute between Howard Hughes, the owner of Trans World Airlines and Owen Brewster, chairman of the Senate War Investigating Committee. Hughes claimed that Brewster was being paid by Pan American World Airways (Pan Am) to persuade the United States government to set up an official worldwide monopoly under its control. Part of this plan was to force all existing American carriers with overseas operations to close down or merge with Pan Am. As the owner of Trans World Airlines, Hughes posed a serious threat to this plan. Hughes claimed that Brewster had approached him and suggested he merge Trans World with Pan Am. Pearson and Anderson began a campaign against Brewster. They reported that Pan Am had provided Bewster with free flights to Hobe Sound, Florida, where he stayed free of charge at the holiday home of Pan Am Vice President Sam Pryor. As a result of this campaign Bewster lost his seat in Congress.

In the late 1940s Anderson became friendly with Joseph McCarthy. As he pointed out in his autobiography, Confessions of a Muckraker, "Joe McCarthy... was a pal of mine, irresponsible to be sure, but a fellow bachelor of vast amiability and an excellent source of inside dope on the Hill." McCarthy began supplying Anderson with stories about suspected communists in government. Pearson refused to publish these stories as he was very suspicious of the motives of people like McCarthy. In fact, in 1948, Pearson began investigating J. Parnell Thomas, the Chairman of the House of Un-American Activities Committee. It was not long before Thomas' secretary, Helen Campbell, began providing information about his illegal activities. On 4th August, 1948, Pearson published the story that Thomas had been putting friends on his congressional payroll. They did no work but in return shared their salaries with Thomas.

Called before a grand jury, J. Parnell Thomas availed himself to the 5th Amendment, a strategy that he had been unwilling to accept when dealing with the Hollywood Ten. Indicted on charges of conspiracy to defraud the government, Thomas was found guilty and sentenced to 18 months in prison and forced to pay a $10,000 fine. Two of his fellow inmates in Danbury Federal Correctional Institution were Lester Cole and Ring Lardner Jr. who were serving terms as a result of refusing to testify in front of Thomas and the House of Un-American Activities Committee.

In 1949 Pearson criticised the Secretary of Defence, James Forrestal, for his conservative views on foreign policy. He told Jack Andersonthat he believed Forrestal was "the most dangerous man in America" and claimed that if he was not removed from office he would "cause another world war". Pearson also suggested that Forrestal was guilty of corruption. Pearson was blamed when Forrestal committed suicide on 22nd May 1949. One journalist, Westbrook Pegler, wrote: "For months, Drew Pearson... hounded Jim Forrestal with dirty aspersions and insinuations, until, at last, exhausted and his nerves unstrung, one of the finest servants that the Republic ever had died of suicide." On 23nd May, 1949, Pearson wrote in his diary that "Pegler had published a column virtually accusing me of murdering Forrestal." The following day he wrote: "Late this afternoon I clapped a libel suit of $250,000 on Pegler". The case was eventually settled out of court.

Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson also began investigating General Douglas MacArthur. In December, 1949, Anderson got hold of a top-secret cable from MacArthur to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, expressing his disagreement with President Harry S. Truman concerning Chaing Kai-shek. On 22nd December, 1949, Pearson published the story that: "General MacArthur has sent a triple-urgent cable urging that Formosa be occupied by U.S. troops." Pearson argued that MacArthur was "trying to dictate U.S. foreign policy in the Far East".

Harry S. Truman and Dean Acheson, the Secretary of State, told MacArthur to limit the war to Korea. MacArthur disagreed, favoring an attack on Chinese forces. Unwilling to accept the views of Truman and Dean Acheson, MacArthur began to make inflammatory statements indicating his disagreements with the United States government.

MacArthur gained support from right-wing members of the Senate such as Joe McCarthy who led the attack on Truman's administration: "With half a million Communists in Korea killing American men, Acheson says, 'Now let's be calm, let's do nothing'. It is like advising a man whose family is being killed not to take hasty action for fear he might alienate the affection of the murders."

On 7th October, 1950, Douglas MacArthur launched an invasion of North Korea by the end of the month had reached the Yalu River, close to the frontier of China. On 20th November, Pearson wrote in his column that the Chinese were following a strategy that was "sucking our troops into a trap." Three days later the Chinese Army launched an attack on MacArthur's army. North Korean forces took Seoul in January 1951. Two months later, Harry S. Truman removed MacArthur from his command of the United Nations forces in Korea.

Joe McCarthy continued to provide Jack Anderson with a lot of information. In his autobiography, Confessions of a Muckraker, Anderson pointed out: "At my prompting he (McCarthy) would phone fellow senators to ask what had transpired this morning behind closed doors or what strategy was planned for the morrow. While I listened in on an extension he would pump even a Robert Taft or a William Knowland with the handwritten questions I passed him."

In return, Anderson provided McCarthy with information about politicians and state officials he suspected of being "communists". Anderson later recalled that his decision to work with McCarthy "was almost automatic.. for one thing, I owed him; for another, he might be able to flesh out some of our inconclusive material, and if so, I would no doubt get the scoop." As a result Anderson passed on his file on the presidential aide, David Demarest Lloyd.

On 9th February, 1950, Joe McCarthy made a speech in Salt Lake City where he attacked Dean Acheson, the Secretary of State, as "a pompous diplomat in striped pants". He claimed that he had a list of 57 people in the State Department that were known to be members of the American Communist Party. McCarthy went on to argue that some of these people were passing secret information to the Soviet Union. He added: "The reason why we find ourselves in a position of impotency is not because the enemy has sent men to invade our shores, but rather because of the traitorous actions of those who have had all the benefits that the wealthiest nation on earth has had to offer - the finest homes, the finest college educations, and the finest jobs in Government we can give."

The list of names was not a secret and had been in fact published by the Secretary of State in 1946. These people had been identified during a preliminary screening of 3,000 federal employees. Some had been communists but others had been fascists, alcoholics and sexual deviants. As it happens, if McCarthy had been screened, his own drink problems and sexual preferences would have resulted in him being put on the list.

Pearson immediately launched an attack on Joe McCarthy. He pointed out that only three people on the list were State Department officials. He added that when this list was first published four years ago, Gustavo Duran and Mary Jane Keeney had both resigned from the State Department (1946). He added that the third person, John S. Service, had been cleared after a prolonged and careful investigation. Pearson also argued that none of these people had been named were members of the American Communist Party.

Jack Anderson asked Pearson to stop attacking McCarthy: "He is our best source on the Hill." Pearson replied, "He may be a good source, Jack, but he's a bad man."

On 20th February, 1950, Joe McCarthy made a speech in the Senate supporting the allegations he had made in Salt Lake City. This time he did not describe them as "card-carrying communists" because this had been shown to be untrue. Instead he argued that his list were all "loyalty risks". He also claimed that one of the president's speech-writers, was a communist. Although he did not name him, he was referring to David Demarest Lloyd, the man that Anderson had provided information on.

Lloyd immediately issued a statement where he defended himself against McCarthy's charges. President Harry S. Truman not only kept him on but promoted him to the post of Administrative Assistant. Lloyd was indeed innocent of these claims and McCarthy was forced to withdraw these allegations. As Anderson admitted: "At my instigation, then, Lloyd had been done an injustice that was saved from being grevious only by Truman's steadfastness."

McCarthy now informed Jack Anderson that he had evidence that Professor Owen Lattimore, director of the Walter Hines Page School of International Relations at Johns Hopkins University, was a Soviet spy. Pearson, who knew Lattimore, and while accepting he held left-wing views, he was convinced he was not a spy. In his speeches, McCarthy referred to Lattimore as "Mr X... the top Russian spy... the key man in a Russian espionage ring."

On 26th March, 1950, Pearson named Lattimore as McCarthy's Mr. X. Pearson then went onto defend Lattimore against these charges. McCarthy responded by making a speech in Congress where he admitted: "I fear that in the case of Lattimore I may have perhaps placed too much stress on the question of whether he is a paid espionage agent."

McCarthy then produced Louis Budenz, the former editor of The Daily Worker. Budenz claimed that Lattimore was a "concealed communist". However, as Jack Anderson admitted: "Budenz had never met Lattimore; he spoke not from personal observation of him but from what he remembered of what others had told him five, six, seven and thirteen years before."

Pearson now wrote an article where he showed that Budenz was a serial liar: "Apologists for Budenz minimize this on the ground that Budenz has now reformed. Nevertheless, untruthful statements made regarding his past and refusal to answer questions have a bearing on Budenz's credibility." He went on to point out that "all in all, Budenz refused to answer 23 questions on the ground of self-incrimination".

Owen Lattimore was eventually cleared of the charge that he was a Soviet spy or a secret member of the American Communist Party and like several other victims of McCarthyism, he went to live in Europe and for several years was professor of Chinese studies at Leeds University.

Despite the efforts of Jack Anderson, by the end of June, 1950, Drew Pearson had written more than forty daily columns and a significant percentage of his weekly radio broadcasts, that had been devoted to discrediting the charges made by Joseph McCarthy. He now decided to take on Pearson and he told Anderson: "Jack, I'm going to have to go after your boss. I mean, no holds barred. I figure I've already lost his supporters; by going after him, I can pick up his enemies." McCarthy, when drunk, told Assistant Attorney General Joe Keenan, that he was considering "bumping Pearson off".

On 15th December, 1950, McCarthy made a speech in Congress where he claimed that Pearson was "the voice of international Communism" and "a Moscow-directed character assassin." McCarthy added that Pearson was "a prostitute of journalism" and that Pearson "and the Communist Party murdered James Forrestal in just as cold blood as though they had machine-gunned him."

Over the next two months Joseph McCarthy made seven Senate speeches on Drew Pearson. He called for a "patriotic boycott" of his radio show and as a result, Adam Hats, withdrew as Pearson's radio sponsor. Although he was able to make a series of short-term arrangements, Pearson was never again able to find a permanent sponsor. Twelve newspapers cancelled their contract with Pearson.

Joe McCarthy and his friends also raised money to help Fred Napoleon Howser, the Attorney General of California, to sue Pearson for $350,000. This involved an incident in 1948 when Pearson accused Howser of consorting with mobsters and of taking a bribe from gambling interests. Help was also given to Father Charles Coughlin, who sued Pearson for $225,000. However, in 1951 the courts ruled that Pearson had not libeled either Howser or Coughlin.

Only the St. Louis Star-Times defended Pearson. As its editorial pointed out: "If Joseph McCarthy can silence a critic named Drew Pearson, simply by smearing him with the brush of Communist association, he can silence any other critic." However, Pearson did get the support of J. William Fulbright, Wayne Morse, Clinton Anderson, William Benton and Thomas Hennings in the Senate.

In October, 1953, Joe McCarthy began investigating communist infiltration into the military. Attempts were made by McCarthy to discredit Robert T. Stevens, the Secretary of the Army. The president, Dwight Eisenhower, was furious and now realised that it was time to bring an end to McCarthy's activities.

The United States Army now passed information about McCarthy to journalists who were known to be opposed to him. This included the news that McCarthy and Roy Cohn had abused congressional privilege by trying to prevent David Schine from being drafted. When that failed, it was claimed that Cohn tried to pressurize the Army into granting Schine special privileges. Pearson published the story on 15th December, 1953.

Some figures in the media, such as writers George Seldes and I. F. Stone, and cartoonists, Herb Block and Daniel Fitzpatrick, had fought a long campaign against McCarthy. Other figures in the media, who had for a long time been opposed to McCarthyism, but were frightened to speak out, now began to get the confidence to join the counter-attack. Edward Murrow, the experienced broadcaster, used his television programme, See It Now, on 9th March, 1954, to criticize McCarthy's methods. Newspaper columnists such as Walter Lippmann also became more open in their attacks on McCarthy.

The senate investigations into the United States Army were televised and this helped to expose the tactics of Joseph McCarthy. One newspaper, the Louisville Courier-Journal, reported that: "In this long, degrading travesty of the democratic process, McCarthy has shown himself to be evil and unmatched in malice." Leading politicians in both parties, had been embarrassed by McCarthy's performance and on 2nd December, 1954, a censure motion condemned his conduct by 67 votes to 22.

McCarthy also lost the chairmanship of the Government Committee on Operations of the Senate. He was now without a power base and the media lost interest in his claims of a communist conspiracy. As one journalist, Willard Edwards, pointed out: "Most reporters just refused to file McCarthy stories. And most papers would not have printed them anyway."

In 1956 Drew Pearson began investigating the relationship between Lyndon B. Johnson and two businessmen, George R. Brown and Herman Brown. Pearson believed that Johnson had arranged for the Texas-based Brown and Root Construction Company to avoid large tax bills. Johnson brought an end to this investigation by offering Pearson a deal. If Pearson dropped his Brown-Root crusade, Johnson would support the presidential ambitions of Estes Kefauver. Pearson accepted and wrote in his diary (16th April, 1956): "This is the first time I've ever made a deal like this, and I feel a little unhappy about it. With the Presidency of the United States at stake, maybe it's justified, maybe not - I don't know."

Jack Anderson also helped Pearson investigate stories of corruption inside the administration of President Dwight Eisenhower. They discovered that Eisenhower had received gifts worth more than $500,000 from "big-business well-wishers." In 1957 Anderson threaten to quit because these stories always appeared under Pearson's name. Pearson responded by promising him more bylines and pledged to leave the column to him when he died.

Pearson and Anderson began investigating the presidential assistant Sherman Adams. The former governor of New Hampshire, was considered to be a key figure in Eisenhower's administration. Anderson discovered that Bernard Goldfine, a wealthy industrialist, had given Adams a large number of presents. This included suits, overcoats, alcohol, furnishings and the payment of hotel and resort bills. Anderson eventually found evidence that Adams had twice persuaded the Federal Trade Commission to "ease up its pursuit of Goldfine for putting false labels on the products of his textile plants."

The story was eventually published in 1958 and Adams was forced to resign from office. However, Jack Anderson was much criticized for the way he carried out his investigation and one of his assistants, Les Whitten, was arrested by the FBI for receiving stolen government documents.

In 1960 Pearson supported Hubert Humphrey in his efforts to become the Democratic Party candidate. However, those campaigning for John F. Kennedy, accused him of being a draft dodger. As a result, when Humphrey dropped out of the race, Pearson switched his support to Lyndon B. Johnson. However, it was Kennedy who eventually got the nomination.

Pearson now supported Kennedy's attempt to become president. One of the ways he helped his campaign was to investigate the relationship between Howard Hughes and Richard Nixon. Pearson and Anderson discovered that in 1956 the Hughes Tool Company provided a $205,000 loan to Nixon Incorporated, a company run by Richard's brother, Francis Donald Nixon. The money was never paid back. Soon after the money was paid the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) reversed a previous decision to grant tax-exempt status to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

This information was revealed by Pearson and Jack Anderson during the 1960 presidential campaign. Nixon initially denied the loan but later was forced to admit that this money had been given to his brother. It was claimed that this story helped John F. Kennedy defeat Nixon in the election.

In 1963 Senator John Williams of Delaware began investigating the activities of Bobby Baker. As a result of his work, Baker resigned as the secretary to Lyndon B. Johnson on 9th October, 1963. During his investigations Williams met Don B. Reynolds and persuaded him to appear before a secret session of the Senate Rules Committee.

Reynolds told B. Everett Jordan and his committee on 22nd November, 1963, that Johnson had demanded that he provided kickbacks in return for him agreeing to this life insurance policy. This included a $585 Magnavox stereo. Reynolds was also told by Walter Jenkins that he had to pay for $1,200 worth of advertising on KTBC, Johnson's television station in Austin. Reynolds had paperwork for this transaction including a delivery note that indicated the stereo had been sent to the home of Johnson.

Don B. Reynolds also told of seeing a suitcase full of money which Bobby Baker described as a "$100,000 payoff to Johnson for his role in securing the Fort Worth TFX contract". Reynolds also provided evidence against Matthew H. McCloskey. He suggested that he given $25,000 to Baker in order to get the contract to build the District of Columbia Stadium. His testimony came to an end when news arrived that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated.

As soon as Johnson became president he contacted B. Everett Jordan to see if there was any chance of stopping this information being published. Jordan replied that he would do what he could but warned Johnson that some members of the committee wanted Reynold's testimony to be released to the public. On 6th December, 1963, Jordan spoke to Johnson on the telephone and said he was doing what he could to suppress the story because " it might spread (to) a place where we don't want it spread."

Abe Fortas, a lawyer who represented both Lyndon B. Johnson and Bobby Baker, worked behind the scenes in an effort to keep this information from the public. Johnson also arranged for a smear campaign to be organized against Reynolds. To help him do this J. Edgar Hoover passed to Johnson the FBI file on Reynolds.

On 17th January, 1964, the Committee on Rules and Administration voted to release to the public Reynolds' secret testimony. Johnson responded by leaking information from Reynolds' FBI file to Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson. On 5th February, 1964, the Washington Post reported that Reynolds had lied about his academic success at West Point. The article also claimed that Reynolds had been a supporter of Joseph McCarthy and had accused business rivals of being secret members of the American Communist Party. It was also revealed that Reynolds had made anti-Semitic remarks while in Berlin in 1953.

A few weeks later the New York Times reported that Lyndon B. Johnson had used information from secret government documents to smear Don B. Reynolds. It also reported that Johnson's officials had been applying pressure on the editors of newspapers not to print information that had been disclosed by Reynolds in front of the Senate Rules Committee.

In 1966 attempts were made to deport Johnny Roselli as an illegal alien. Roselli moved to Los Angeles where he went into early retirement. It was at this time he told attorney, Edward Morgan: "The last of the sniper teams dispatched by Robert Kennedy in 1963 to assassinate Fidel Castro were captured in Havana. Under torture they broke and confessed to being sponsored by the CIA and the US government. At that point, Castro remarked that, 'If that was the way President Kennedy wanted it, Cuba could engage in the same tactics'. The result was that Castro infiltrated teams of snipers into the US to kill Kennedy".

Morgan took the story to Pearson. The story was then passed on to Earl Warren. He did not want anything to do with it and so the information was then passed to the FBI. When they failed to investigate the story Jack Anderson wrote an article entitled "President Johnson is sitting on a political H-bomb" about Roselli's story. It has been suggested that Roselli started this story at the request of his friends in the Central Intelligence Agency in order to divert attention from the investigation being carried out by Jim Garrison.

In 1968 Jack Anderson and Drew Pearson published The Case Against Congress. The book documented examples of how politicians had "abused their power and priviledge by placing their own interests ahead of those of the American people". This included the activities of Bobby Baker, James Eastland, Lyndon B. Johnson, Dwight Eisenhower, Hubert Humphrey, Everett Dirksen, Thomas J. Dodd, John McClellan and Clark Clifford.

On 18th July, 1969, Mary Jo Kopechne, died while in the car of Edward Kennedy. Pearson began investigating the case when he died on 1st September. Chalmers Roberts of the Washington Post wrote: "Drew Pearson was a muckraker with a Quaker conscience. In print he sounded fierce; in life he was gentle, even courtly. For thirty-eight years he did more than any man to keep the national capital honest."

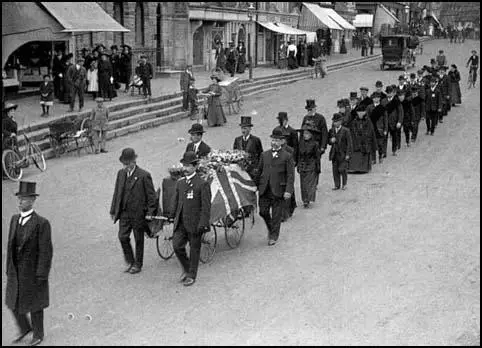

On this day in 1901 George Brinkhurst makes a speech at the East Grinstead Anti-Compulsory Vaccination Society meeting. Frank Brinkhurst was a committed Nonconformist and was a member of the Moat Congregational Church. His sons, George and Frank, shared his religious beliefs. Like most Nonconformists in East Grinstead, John, George and Frank Brinkhurst were all supporters of the Liberal Party. George and Frank were both members of the East Grinstead Urban Council and tended to support reformers such as Edward Steer, Joseph Rice and Thomas Hartigan.

George and Frank were strong supporters of Edward Steer's proposal that the East Grinstead Urban Council should provide electric street lighting. The scheme was opposed by Wallace Hills and other conservative members of the Urban Council. Edward Steer accused Hills of being influenced by his position as a director of the East Grinstead Water and Gas Company. George Brinkhurst complained about the way Hills had reported the issue in The East Grinstead Observer and called for him to be excluded from council meetings.

George and Frank Brinkhurst were both members of the East Grinstead Anti-Compulsory Vaccination Society. Both men refused to have their children vaccinated. The main argument put forward by George Brinkhurst was that it was an example of "the toffs experimenting on the poor".

On this day in 1904 political activist Lester Hutchinson was born. His mother Mary Knight, was a Labour Concillor in Manchester. He was educated at Bootham School and the University of Edinburgh. After leaving university Hutchinson worked as a journalist.

Hutchinson was a member of the League Against Imperialism and worked for the Indian Daily Mail. In India throughout 1928 and 1929 there was a strong wave of strikes, on the railroads, in ironworks and in the textile industry. Trade union numbers and organisation grew rapidly during this period.

The British Government initiated a Committee headed by Sir Charles Fawcett. The arrests of prominent trade unionists and socialists were part of the preparation for the issue of the report. This included Hutchinson, Philip Spratt, Ben Bradley, and 30 other trade unionists, were imprisoned by the Indian after the Meerut Conspiracy Trial in 1929.

A member of the Labour Party he was elected to represent Rusholme division of Manchester in the 1945 General Election. In the House of Commons Hutchinson associated with a group of left-wing members that included John Platts-Mills, Konni Zilliacus, Leslie Solley, Ian Mikardo, Barbara Castle, Sydney Silverman, Geoffrey Bing, Emrys Hughes, D. N. Pritt, William Warbey, William Gallacher and Phil Piratin.

In April 1948 John Platts-Mills organized a petition in support of Pietro Nenni and the Italian Socialist Party in its general election campaign. He gained support from 27 other MPs including Solley. This went against government policy and Platts-Mills was expelled from the party and Hutchinson was warned about his future conduct.

Ernest Bevin signed the North Atlantic Treaty in Washington on 4th April 1949. Solley completely opposed the treaty arguing that it went against the charter of the United Nations, would accelerate the arms race and make it more difficult to achieve a united Europe. On 12th May, 1949, Solley was only one of only six Labour MPs to vote against the signing of the NATO treaty. Four days later Hutchinson, along with Leslie Solley and Konni Zilliacus, were expelled from the Labour Party. Lester Hutchinson died in February 1983

On this day in 1905 civil rights journalist Carey McWilliams was born. Carey McWilliams was born in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, on 13th December, 1905. The family moved to California in 1922 and McWilliams attended the University of Southern California, from which he obtained a law degree in 1927.

McWilliams practiced law in Los Angeles and developed a reputation for taking up the cases of the underprivileged. He also became friends with the writer, Upton Sinclair, and helped him in his various political campaigns. Another contact during this period was H.L. Mencken who published some of his early journalism. In 1929 McWilliams published a biography of Ambrose Bierce. McWilliams, who considered himself a socialist, was a member of numerous left-wing political and legal organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Lawyers Guild. He was also involved in the campaign to free Tom Mooney, a trade union leader who had been convicted of a bombing which occurred in San Francisco in 1916.

McWilliams continued to work in journalism and had several articles published in The Nation. He also served as a trial examiner for the National Labor Relations Board. His book on migrant farm workers, Factories in the Field: The Story of Migratory Farm Labor in California, was published in 1939. A supporter of Culbert Olson, McWilliams agreed to become head California's Division of Immigration and Housing that year. Over the next few years he attempted to improve agricultural working conditions and wages. As governor Olson tried to introduce an advanced New Deal in California. In Olson's words that would provide "economic security from the cradle to the grave, under a government that recognizes the right to an education, to employment on a basis of just reward, and to retirement at old age in comfort and decency, as inalienable as the right to life itself."

Olson's policies were attacked by his Republican Party opponent, Earl Warren. During the 1942 governor election campaign, Warren promised audiences that his first official act would be to fire McWilliams. As soon as Warren was elected in 1942, McWilliams resigned his post. He now concentrated on journalism and wrote several books including Prejudice: Japanese-Americans (1944), A Mask for Privilege: Anti-Semitism in America (1948) and North from Mexico: The Spanish-Speaking People of the US (1949).

Carey McWilliams was considered to be a dangerous radical and was called before the Un-American Activities Committee and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover placed him on the Custodial Detention List, making him a candidate for detention in case of national emergency. An early opponent of McCarthyism in 1950 he published Witch Hunt: The Revival of Heresy. He also helped in the legal defence of John Howard Lawson and Dalton Trumbo, two of the Hollywood Ten.

In 1951 McWilliams moved to New York City to work at The Nation under then editor Freda Kirchwey. He became editor of the magazine in 1955. He instituted investigative reports on domestic issues. This included a series on Jim Crow Laws and articles on consumer issues by Ralph Nader. In November 1960 McWilliams was the first American reporter to reveal that the CIA was training a group of Cuban exiles in Guatemala for the Bay of Pigs Invasion.

Carey McWilliams upset a large number of people on the left with his views on the assassination of John F. Kennedy. One of those was his friend Mark Lane who tried to find a magazine to publish his article of the assassination. “The obvious choice, I thought, was the Nation. Its editor, Carey McWilliams, was an acquaintance. He had often asked me to write a piece for him… McWilliams seemed pleased to hear from me and delighted when I told him I had written something I wished to give to the Nation. When he learned of the subject matter, however, his manner approached panic.” McWilliams told Lane: “We cannot take it. We don’t want it. I am sorry but we have decided not to touch that subject.”

McWilliams also gave his support to the Warren Commission Report. It has been suggested that the critics of the lone-gunman theory were particularly hurt by his support. In a debate that took place at Beverly Hills High School on 4th December, 1964, Abraham L. Wirin, chief counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union in California and a man who had been closely associated in the past with the American Communist Party, told the audience that he tried to make up his own mind on important issues, but in the case of the Warren Commission he relied on the opinions of people who he could trust: "I consider Carey McWilliams and The Nation, as an individual and a newspaper, respectively, whose judgment I respect. I do not consider Carey McWilliams or The Nation, a person or a newspaper, which would participate in a fraud, or would condone it." Wirin pointed out The Nation had carried an article in support of the Warren Report and added: "now, that carries a lot of weight with me." Carey McWilliams died on 27th June, 1980.

On this day in 1914 Larry Parks was born in Olathe, Kansas. He moved to Hollywood and during the early 1940s obtained a series of minor roles in movies such as Harmon of Michigan (1941), Harvard, Here I Come (1941), Mystery Ship (1941), Alias Boston Blackie (1942), Atlantic Convoy (1942), Canal Zone (1942), Deerslayer (1943), Stars on Parade (1944), The Black Parachute (1944) and Jam Session (1944).

Parks became a Hollywood star after his lead performance in the Academy Award winning The Jolson Story (1946). Nominated as best actor of the year, Parks followed this film with Renegades (1946), Down to Earth (1947), The Swordsman (1947), The Gallant Blade (1948), Jolson Sings Again (1949) and Jealousy (1949).

During this period the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) opened its hearings concerning communist infiltration of the motion picture industry. The chief investigator for the committee was Robert E. Stripling. The first people it interviewed included Ronald Reagan, Gary Cooper, Ayn Rand, Jack L. Warner, Robert Taylor, Adolphe Menjou, Robert Montgomery, Walt Disney, Thomas Leo McCarey and George L. Murphy. These people named several possible members of the American Communist Party.

As a result their investigations, the HUAC announced it wished to interview nineteen members of the film industry that they believed might be members of the American Communist Party. This included Larry Parks, Herbert Biberman, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz, John Howard Lawson, Waldo Salt, Bertolt Brecht, Richard Collins, Gordon Kahn, Robert Rossen, Lewis Milestone and Irving Pichel.

The first ten witnesses called to appear before the HUAC, Biberman, Bessie, Cole, Maltz, Scott, Trumbo, Dmytryk, Lardner, Ornitz and Lawson, refused to cooperate at the September hearings and were charged with "contempt of Congress". Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The courts disagreed and each was sentenced to between six and twelve months in prison. The case went before the Supreme Court in April 1950, but with only Justices Hugo Black and William Douglas dissenting, the sentences were confirmed.

On 8th March, 1951, the HUAC committee began an "Investigation of Communism in the Entertainment Field". The chairman was John S. Wood, and other members included Harold Velde of Illinois, Francis Walter of Pennsylvania, Morgan M. Moulder of Missouri, Clyde Doyle of California, James B. Frazier of Tennessee, Bernard W. Kearney of New York and Charles E. Potter of Michigan. Louis Russell was the senior investigator and Frank S. Tavenner, was chief counsel.

Larry Parks gave evidence on 21st March, 1951. He admitted that he joined the American Communist Party in 1941. He joined because it "fulfilled certain needs of a young man that was liberal of thought, idealistic, who was for the underprivileged, the underdog". At first he refused to name other members of the party: "I would prefer not to mention names, if it is at all possible, of anyone. I don't think it is fair to people to do this. I have come to you at your request. I have come and willingly tell you about myself. I think that, if you would allow me, I would prefer not to be questioned about names. And I will tell you everything that I know about myself, because I feel I have done nothing wrong, and 1 will answer any question that you would like to put to me about myself. I would prefer, if you will allow me, not to mention other people's names.... The people at that time as I knew them-this is my opinion of them. This is my honest opinion: That these are people who did nothing wrong, people like myself.... And it seems to me that this is not the American way of doing things to force a man who is under oath and who has opened himself as wide as possible to this committee - and it hasn't been easy to do this -to force a man to do this is not American justice."

However, Parks did agree to name members in a private session of the HUAC. This included Joseph Bromberg, Lee J. Cobb, Morris Carnovsky, John Howard Lawson, Karen Morley, Anne Revere, Gale Sondergaard, Lloyd Gough and Victor Kilian. Three days later Paul Jarrico, who was due to appear before the HUAC, told the New York Times, that he was unwilling to follow the example of Parks: "If I have to choose between crawling in the mud with Larry Parks or going to jail like my courageous friends of the Hollywood Ten, I shall certainly choose the latter."

Despite giving the names of other former members of the Communist Party, Parks was still blacklisted. After failing to get work in Hollywood, Parks asked to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee again in an effort to provide more information about communism. He argued in a letter dated 15th July, 1953: "After careful consideration I wish to file a clarifying statement of my point of view on the Communist problem with your Committee. I am now convinced that my previous testimony improperly reflects my true attitude towards the malignancy of the Communist Party. If there is any way in which I can further aid in exposing the methods of entrapment and deceit through which Communist conspirators have gained the adherence of American idealists and liberals, I hope the Committee will advise me. Above all, I wish to make it clear that I support completely the objectives of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. I believe fully that Communists and Communist intrigues should be thoroughly exposed and isolated and thus rendered impotent."

Despite this appeal he failed to get his name removed from the blacklist but he did continue to perform on the stage and appeared in two long running plays, Teahouse of the August Moon and Any Wednesday and two Broadway shows. Larry Parks died of a heart attack on 13th April, 1975.

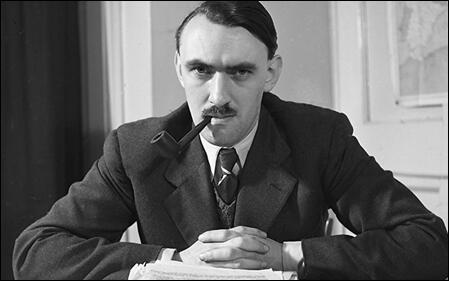

On this day in 1914 historian Alan Bullock, the son of Frank Bullock, was born in Trowbridge, Wiltshire. His father was a gardener and his mother, a maid. When he was a child his parents moved to Bradford where his father became a Unitarian minister and leader of the city's Literary Society. As one biographer pointed out: "The Bullocks were poor but high-minded, and spent what money they could on buying books and going to concerts. Father and son were close; by the time Alan was 16, they were talking together in Latin." He later argued that his father was "an autodidact of extraordinary mental power and spiritual feeling, who deeply affected all who knew him."

Bullock won a place at Bradford Grammar School. Another pupil at the school was Denis Healey: "Of all my contemporaries at Bradford, I most admired Alan Bullock... He was two years older than I, and won the Senior Essay Prize of the National Book Council in 1930, the same year as I won the Junior Essay Prize.... Alan had a range of knowledge and interests unique in our school; he seemed equally familiar with Wagner's letters and Joyce's Ulysses."

Bullock won a scholarship to Wadham College, where he studied for five years to win a rare double first in classics (1936) and modern history (1938). Soon after leaving Oxford University the outbreak of the Second World War took place. His asthma disqualified him from military service, and during the conflict he worked for the BBC Overseas Service.

In 1945 he was appointed as a modern history fellow at New College. Over the next few years he worked on his first book, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1952). Mark Frankland has argued that the book on Adolf Hitler "remains both a standard work and an absorbing piece of modern historical writing. The book on which his reputation as a historian rests, it played to his strengths as a biographer who had the knack of penetrating the minds of others." This was followed by The Liberal Tradition from Fox to Keynes (1956) and a biography of Ernest Bevin, the trade union leader, The Life and Times of Ernest Bevin (1960).

In 1960 Bullock was appointed as founding master of St Catherine's College, the only new college for both undergraduates and graduates built in Oxford University in the 20th century. Mark Frankland claimed: "He was a powerfully built man, and some people found him domineering... He was Oxford's first full-time vice-chancellor (1969-73), serving during a difficult period of student unrest. His build, strong voice and irrepressible Yorkshire accent gave him an air of strength that was quite undonnish. This served him well when it came to keeping unruly undergraduates within limits." He was aware of this trait and once commented: "Bullock by name, and Bullock by nature."

Bullock was chairman of the Committee on Reading and Other Uses of English Language (1972-74) that resulted in the publication of the report A Language of Life (1975). The following year he chaired an investigation into industrial democracy (1976). He also served as chairman of the Tate Gallery (1973-1980).

Other books by Bullock include Faces of Europe (1980), The Humanist Tradition in the West (1985), Has History a Future? (1987), Hitler and Stalin: Parrallel Lives (1991) a biography of his father, Building Jerusalem (2000) and a single-volume biography of Ernest Bevin (2002).

Peter Dickson has argued: "Three intellectual characteristics are discernible. First is the apparently effortless ability to absorb huge amounts of information, whether from the unending Nuremberg documents, the trades-union or Foreign Office archives, or the enormous corpus of primary and secondary printed material on Stalinist Russia. Second is the ability to arrange this information objectively into convincing patterns, so that interpretation and judgement are always close behind description. Bullock wrote for truth, not for effect, and eschewed the heating up of controversy not unknown in other contemporary historians. Third, overlapping with this, are a breadth of historical perspective, and a force of imagination, which resulted from intuition as much as formal study." Alan Bullock died on 2nd February, 2004.

On this day in 1940 Graham Greene claimed in an article in The Spectator that J. B. Priestley "became in the months after Dunkirk a leader second only in importance to Mr Churchill. And he gave us what our other leaders have always failed to give us - an ideology." The reason that Greene said this was that during the Second World War Priestley became the presenter of Postscripts, a BBC Radio radio programme that followed the nine o'clock news on Sunday evenings. Starting on 5th June 1940, Priestley built up such a following that after a few months it was estimated that around 40 per cent of the adult population in Britain was listening to the programme.

On 21st July, 1940, he argued: "We cannot go forward and build up this new world order, and this is our war aim, unless we begin to think differently one must stop thinking in terms of property and power and begin thinking in terms of community and creation. Take the change from property to community. Property is the old-fashioned way of thinking of a country as a thing, and a collection of things in that thing, all owned by certain people and constituting property; instead of thinking of a country as the home of a living society with the community itself as the first test."

Some members of the Conservative Party complained about Priestley expressing left-wing views on his radio programme. Margaret Thatcher has argued that "J.B. Priestley gave a comfortable yet idealistic gloss to social progress in a left-wing direction." As a result Priestley made his last talk on 20th October 1940. These were later published in book form as Britain Speaks (1940).

Priestley and a group of friends now established the 1941 Committee. One of its members, Tom Hopkinson, later claimed that the motive force was the belief that if the Second World War was to be won "a much more coordinated effort would be needed, with stricter planning of the economy and greater use of scientific know-how, particularly in the field of war production." Priestley became the chairman of the committee and other members included Edward G. Hulton, Kingsley Martin, Richard Acland, Michael Foot, Tom Winteringham, Vernon Bartlett, Violet Bonham Carter, Konni Zilliacus, Victor Gollancz, Storm Jameson and David Low.

In December 1941 the committee published a report that called for public control of the railways, mines and docks and a national wages policy. A further report in May 1942 argued for works councils and the publication of "post-war plans for the provision of full and free education, employment and a civilized standard of living for everyone."

Some members of the Labour Party disapproved of the electoral truce between the main political parties during the Second World War and in 1942 J. B. Priestley and Richard Acland formed the socialist Common Wealth Party (CWP). The party advocated the three principles of "Common Ownership", "Vital Democracy" and "Morality in Politics". The party favoured public ownership of land and Acland gave away his Devon family estate of 19,000 acres (8,097 hectares) to the National Trust.

The CWP decided to contest by-elections against Conservative candidates. They needed the support of traditional Labour supporters. Tom Wintringham wrote in September 1942: "The Labour Party, the Trade Unions and the Co-operatives represent the worker's movement, which historically has been, and is now, in all countries the basic force for human freedom... and we count on our allies within the Labour Party who want a more inspiring leadership to support us." Large numbers of working people did support the CWP and this led to victories for Richard Acland in Barnstaple and Vernon Bartlett in Bridgwater.

Over the next two years the CWP also had victories in Eddisbury (John Loverseed), Skipton (Hugh Lawson) and Chelmsford (Ernest Millington). George Orwell wrote: "I think this movement should be watched with attention. It might develop into the new Socialist party we have all been hoping for, or into something very sinister." Orwell, like Kitty Bowler, believed that Richard Acland had the potential to become a fascist leader.

Negotiations went on between the Common Wealth Party and the Labour Party about the 1945 General Election. Acland demanded the right to contest 43 selected Conservative-held seats without opposition from Labour in return for not contesting all other constituencies. After this offer was rejected, Tom Wintringham met with Herbert Morrison, and suggested this be lowered to "twenty middle-class Tory seats". Morrison made it clear that his party was unwilling to agree to any proposal that involved Labour candidates standing-down.

Tom Wintringham was commissioned by Victor Gollancz to write a book, Your MP. The book sold over 200,000 copies and was a best-seller during the 1945 general election campaign. The book contained an appendix detailing how 310 Conservative MPs voted in eight key debates between 1935 and 1943. However, this book seemed to help the Labour Party as they ended up with 393 seats, whereas only one of the CWP twenty-three candidates was successful - Ernest Millington at Chelmsford, where there was no Labour contestant.

In 1946 J. B. Priestley wrote one of his best-known plays, An Inspector Calls. It was later turned into a film starring Alastair Sim. However, as his biographer, Judith Cook, has pointed out: "While Priestley's plays have always been popular outside London and abroad, it became fashionable over the years to consider them too old-fashioned for metropolitan audiences."

On this day in 1960 feminist and activist Dora Marsden died. Dora, the daughter of a woollen waste dealer, was born in Marsden, near Huddersfield, on 5th March 1882. Her father left home soon after she was born and the family suffered extreme poverty when she was a child. At the age of 13 she became a probationer and then a pupil-teacher at the local school.

In 1900 she entered Owens College on a Queen's Scholarship. While at the college she met Christabel Pankhurst, Isabella Ford, Teresa Billington and Eva Gore-Booth. Marsden graduated in 1903 with an upper second-class degree and taught in Leeds, Colchester and Manchester.

In 1908 she was appointed headmistress of the Altrincham Pupil-Teacher Centre on a salary of £130 per year. Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990) has pointed out: "The Pupil-Teacher Centre had been set up in the Technical Institute's buildings in George Street, Altrincham, to serve pupils from Altrincham, Knutsford, Ashton-upon-Mersey, and Lynn. Originally it was conceived as a temporary facility until a new secondary school could be built which would also incorporate the training of teachers."

Dora Marsden joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Sylvia Pankhurst described her as "a Yorkshire lass, very tiny with a winsome face, sparkling with animation with laughing golden eyes who had a gift of ready wit and a repartee which, linked with imperturbable good humour made her irresistible to the crowd." By 1908 she was organising demonstrations and speaking at public meetings alongside Christabel Pankhurst and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence.

Rebecca West was also impressed with Dora Marsden: "She (Dora Marsden) was one of the most marvellous personalities that the nation has ever produced. She had, to begin with, the most exquisite beauty of person. She was hardly taller than a child, but she was not just a small woman; she was a perfectly proportioned fairy. She was the only person I have ever met who could so accurately have been described as flower-like that one could have put it down on her passport. And on many other planes she was remarkable."

In March 1909 Marsden resigned as headmistress of the Altrincham Pupil-Teacher Centre to become a paid organiser of the WSPU. Later that month she was arrested with Emily Wilding Davison, Rona Robinson, Patricia Woodlock and Helen Tolson, at a demonstration outside the House of Commons. It was reported in The Times: "the exertions of the women, most of whom were quite young and of indifferent physique, had told upon them and they were showing signs of exhaustion, which made their attempt to break the police line more pitiable than ever." Marsden was sentenced to a month's imprisonment. On her release she became the organiser of the WSPU in North-West Lancashire. Soon afterwards she set up home with Grace Jardine in Southport.

On 4th September 1909 Marsden and Emily Wilding Davison were arrested for breaking windows of a hall in Old Trafford. Two days later she was sentenced to two months' imprisonment in Strangeways. Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999) has pointed out: "Dora Marsden refused to wear prison clothing and spent her time in prison naked, stripping off her clothes each time an attempt was made to dress her." Eventually she was placed in a strait jacket but managed to wriggle out of it, because, according to the prison governor, "she was a very small woman". After going on hunger-strike she was released.

The following month Dora Marsden, Rona Robinson and Mary Gawthorpe decided to take part in another protest. According to Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990): "Dressed in University gowns they entered the meeting and just before Morley began, raised the question of the recent forced feeding of women in Winson Green. There was an uproar, and the three were quickly bundled out and arrested on the pavement." This time they were released without charge.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence wrote to her in prison: "My dear dear brave and beautiful spirit. I have not words to express what I feel about your wonderful courage and heroism. When I think of your face as I saw it in prison my head is full of reverence for the human spirit... A great force is being generated in this movement. We shall send out stronger and stronger thoughts that will change the course of the world's life... My love to you Dora Marsden, sweetest, gentlest and bravest of suffragettes."

Votes for Women reported on 8th October 1909: "No one who knows these three women graduates, or who glances at the numerous photographs which have appeared in the Press can fail to be struck with the pathos of the incident. Mary Gawthorpe, Rona Robinson and Dora Marsden are all slight, petite women who made their protest in a perfectly quiet and gentle manner... They are women moreover, who have done great credit to their respective Universities... Yet they are treated as "hooligans"; treated with such roughness that all 3 had to have medical attention, and hauled before a police magistrate and charged with disorderly behaviour."

Dora Marsden wanted to stage actions that would involve arrest and subsequently, a hunger strike. However, the WSPU wanted to keep their organisers out of prison and Marsden did not get permission for her planned militant activity. On 24th November, 1909, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence remarked: "We are all so anxious that our organisers should not overwork... I know how carried away by your utter devotion and enthusiasm, but I very earnestly beg you pay all due regard to your health, forgive these little warnings dear, they are promoted by concern and affection for yourself."

Marsden ignored this advice and on 4th December, 1909, she joined Helen Tolson and Winson Etherley in attempting to disrupt a meeting in Southport that was being addressed by Winston Churchill. According to the local newspaper "the security for the meeting was unprecedented in the history of the town". While Churchill was speaking he was interrupted by Marsden. Emmeline Pankhurst later recalled that Marsden was "peering through one of the great porthole openings in the slope of the ceiling, was seen a strange elfin form with wan, childish face, broad brow and big grey eyes, looking like nothing real or earthly but a dream waif."

Dora Marsden provided an account of what happened next in Votes for Women: "A dirty hand was was thrust over my mouth, and a struggle began. Finally I was dropped over a ledge, pushed through the broken window, and we began to roll down the steep sloping roof side. Two stewards, crawling up from the other side, shouted out to the two men who had hold of me." Despite being arrested the local magistrate dismissed all charges against them.

Like many women in the WSPU she began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. Marsden and her friends objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were having too much influence over the organization.

Dora Marsden eventually resigned on 27th January 1911. The WSPU leadership started rumours that she had left over some financial irregularity. Theresa McGrath wrote to her saying "are you aware of the rumours that are about concerning your resignation... that you left the accounts for Southport with a deficiency of £500 and that your resignation itself was owing to a request that you should meet the Treasurer for the purpose of going into the matter."

Marsden now joined the Women's Freedom League (WFL), an organisation formed by Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard. Like the WSPU, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. In March 1911 Marsden and her close friend, Grace Jardine, went to work for the WFL newspaper, The Vote.

Dora Marsden attempted to persuade the Women's Freedom League to finance a new feminist journal. When this proposal was refused, Marsden left The Vote. She now joined forces with Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe to establish her own journal. Charles Granville, agreed to become the publisher. On 23rd November, 1911, they published the first edition of The Freewoman. The journal caused a storm when it advocated free love and encouraged women not to get married. The journal also included articles that suggested communal childcare and co-operative housekeeping.

Mary Humphrey Ward, the leader of Anti-Suffrage League argued that the journal represented "the dark and dangerous side of the Women's Movement". According to Ray Strachey, the leader of the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Millicent Fawcett, read the first edition and "thought it so objectionable and mischievous that she tore it up into small pieces". Whereas Maude Royden described it as a "nauseous publication". Edgar Ansell commented that it was "a disgusting publication... indecent, immoral and filthy."

Other feminists were much more supportive, Ada Nield Chew, argued that the was "meat and drink to the sincere student who is out to learn the truth, however unpalatable that truth may be." Benjamin Tucker commented that it was "the most important publication in existence". Floyd Dell, who worked for the Chicago Evening Post argued that before the arrival of The Freewoman: "I had to lie about the feminist movement. I lied loyally and hopefully, but I could not have held out much longer. Your paper proves that feminism has a future as well as a past." Guy Aldred pointed out: "I think your paper deserves to succeed. I will use my influence in the anarchist movement to this end." Others showed their support for the venture by writing without payment for the journal. This included Teresa Billington-Greig, Rebecca West, H. G. Wells, Edward Carpenter, Havelock Ellis, Stella Browne, C. H. Norman, Huntley Carter, Lily Gair Wilkinson and Rose Witcup.

Edwin Bjorkman, writing in the American Review of Reviews, was a great fan of the writing of Dora Marsden: "The writer of The Freewoman editorials has shot into the literary and philosophical firmament as a star of the first magnitude. Although practically unknown before the advent of The Freewoman ... she speaks always with the quietly authoritative air of the writer who has arrived. Her style has beauty as well as force and clarity."

Marsden also attacked the WSPU's strategy of employing militant tactics. She argued that the autocracy of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst prevented independent thought and encouraged followers to become "bondwomen". Marsden went on to suggest "the paramount interest of the WSPU was neither the emancipation of women, nor the vote, but the increase in power of their own organisation." On 7th March, 1912, she wrote: "The Pankhurst party have lost their forthright desire for enfranchisement in their outbalancing desire to raise their own organisation to a position of dictatorship amongst all women's organisations.... The vote was only of secondary importance to the leaders... before every other consideration, political, social or moral comes the aggrandisement of the WSPU itself and the increase of power of their own organisation."

The most controversial aspect of the The Freewoman was its support for free-love. On 23rd November, 1911 Rebecca West wrote an article where she claimed: "Marriage had certain commercial advantages. By it the man secures the exclusive right to the woman's body and by it, the woman binds the man to support her during the rest of her life... a more disgraceful bargain was never struck."