On this day on 2nd January

On this day in 1843, James Stuart, the eldest child of James Gordon Stuart, mill owner, and his wife, Catherine Booth, was born in Newburgh, Fife. He had seven brothers, three of whom died in childhood, and one sister.

Stuart was educated at Madras College and at St Andrews University, where he graduated in 1861. The following year he won a scholarship to Trinity College and after graduation he became an assistant tutor at the University of Cambridge. After meeting Josephine Butler he became an advocate of women's education. In 1867 he gave a series of lectures for Butler's North of England Council for Promoting the Higher Education of Women and the London Society for the Extension of University Education.

His biographer, Colin Matthew, has argued: "He should not, as has sometimes been the case, be seen as sole originator of university extension, but he was certainly its most prominent early activist. In 1875 he was elected the first professor of mechanism and applied mechanics at Cambridge and planned the mechanical science tripos. Practical training cut across Cambridge's theoretical tradition, and Stuart's approach and his radical politics led to criticism."

Stuart, a member of the Liberal Party, developed a close relationship with Mary Gladstone, the daughter of William Ewart Gladstone, the prime minister. He encouraged Mary to read Progress and Poverty, a book by Henry George. Mary wrote in her diary that the book is "supposed to be the most upsetting, revolutionary book of the age. At present Maggie and I both agree with it, and most brilliantly written it is. We had long discussions. He (her father) is reading it too." Stuart told her: "The man (Henry George) is a true man, and that it would do one a great deal of good to spend a day or two with him. I, too, was pleased with his smashing of Malthus. I like to see anyone indignant and angry at any doctrine which makes misery and wrong a natural and inevitable and necessary consequence of the world's ordering." Her father was less impressed commenting "it is well-written but a wild book".

Susan K. Harris, the author of The Cultural Work of the Late Nineteenth-Century Hostess (2004) has argued: "One of the late nineteenth century's most influential works of political economy, Progress and Poverty (1879) attacks the premises of land ownership, rejecting Malthus and arguing that nationalization of rents would remedy all economic ills because the money accruing to the government would enable all other taxes to be repealed... In England, it fell into a vigorous British conversation about land, wages, taxes, and the nature of labour; a conversation that was being conducted on a number of levels, from radical Socialists, who loved the book, to landed aristocrats, who didn't. Everyone, however, recognized that this was a work with which it was necessary to contend, and most understood that it was one of the signal texts for trying to think through solutions to the gap between rich and poor that had manifested itself politically - especially through the Chartist movement - in mid-century, and had remained a source of anxiety for the privileged classes over the remainder of the century."

James Stuart was also a strong supporter of women's suffrage and tried hard to convince Mary Gladstone of the need for reform. In March, 1884, Stuart replied to a letter he received from Mary. He suggested that female franchisement should follow lines already established by those municipalities that did allow women to vote: "To make women more independent of men is, I am convinced, one of the great fundamental means of bringing about justice, morality, and happiness both for married and unmarried men and women. If all Parliament were like the three men you mention, would there be no need for women's votes? Yes, I think there would. There is only one perfectly just, perfectly understanding Being - and that is God." He added: "No man is all-wise enough to select rightly - it is the people's voice thrust upon us, not elicited by us, that guides us rightly."

After unsuccessfully contesting Cambridge University Stuart was elected for Hackney in 1884. In the 1885 General Election he moved to the Hoxton constituency. Over the next few years he campaigned for women's suffrage and the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts and the reform of the House of Lords.

In 1890 Stuart married Laura Elizabeth, daughter of Jeremiah James Colman, the mustard manufacturer they had no children. When his father-in-law died unexpectedly in 1898, Stuart moved to Norfolk and managed the firm. Stuart was defeated in the 1900 General Election but was successful in Sunderland in the 1906 General Election. Stuart's radical political views meant that he was never offered a government post under William Ewart Gladstone, Henry Campbell-Bannerman or Herbert Asquith.

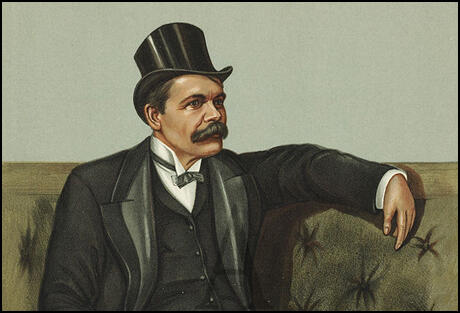

A profile of Stuart in Vanity Fair: "He is many-sided and too enthusiastic. He champions Women's Suffrage because, being a student of Exact Science, he cannot understand Woman. He has, indeed, championed more than one unpopular movement; though he is said to have more intimate knowledge of London political and social questions than anyone else. But he is a wicked Radical, whom the Water Companies hate, although he has friends among the Tories." James Stuart died at his home, Carrow Abbey, Norwich, on 13th October 1913.

On this day in 1858 Beatrice Potter, the eighth daughter of Richard Potter and Laurencina Heyworth, was born on 2nd January, 1858, at Standish House in Gloucestershire. Her grandfather was Richard Potter, the Radical MP for Wigan.

Her father was a wealthy railway entrepreneur and although Beatrice travelled widely with her parents, she received little formal education. However, Beatrice was an intelligent child and read books on philosophy, science and mathematics. She was very impressed by the work of Herbert Spencer and Auguste Comte and came to the conclusion that "self-sacrifice for the good of the community was the greatest of all human characteristics".

In 1883 Potter joined the Charity Organization Society (COS), an organisation that attempted to provide Christian help to those living in poverty. While working with the poor, Beatrice Potter realised that charity would not solve their problems. She began to argue that it was the causes of poverty that needed to be tackled, such as the low standards of education, housing and public health.

In 1882 Beatrice fell in love with one of Britain's leading politicians, Joseph Chamberlain. The relationship ended unhappily and in 1886 Beatrice went to work as a researcher for Charles Booth, who was involved in studying the lives of working people living in London. Beatrice was assigned to study and investigate the lives of the dock workers in the East End. Other topics covered by Beatrice included Jewish immigration and sweated labour in the tailoring trade. Her articles on dock workers and the sweating trades were published in the journal, the Nineteenth Century and as a result was invited to testify before the House of Lords on the subject.

At the time she had fairly conservative opinions about the role of women. In 1886 she wrote about her impressions of Annie Besant: "I felt interested in that powerful woman, with her blighted wifehood and motherhood and her thirst for power and defence of the world. I heard her speak, the only woman I have ever known who is a real orator, who has the gift of public persuasion. But to see her speaking made me shudder. it is not womanly to thrust yourself before the world."

While working in Lancashire Beatrice Potter became interested in the good work achieved by the different co-operative societies that existed in most of Britain's industrial towns. She began involved in writing a book on the subject (The Co-operative Movement) and was advised to contacted Sidney Webb, who had also researched this aspect of working-class life. Her initial reaction was not very positive. She wrote in her diary: "his tiny tadpole body, unhealthy skin, cockney pronunciation, poverty, are all against him". They eventually became close friends and in 1892 she agreed to marry him. She wrote in her diary that "it is only the head that I am marrying." Beatrice had an income of £1,000 that she had inherited from her rich father. This money enabled Sidney to give up his post as a Civil Servant and he now concentrated on his political work.

Sidney Webb was at this time a leading figure in the Fabian Society. The society believed that capitalism had created an unjust and inefficient society. The members, who included Edward Carpenter, Annie Besant, Walter Crane, and George Bernard Shaw agreed that the ultimate aim of the group should be to reconstruct "society in accordance with the highest moral possibilities". Beatrice also shared these views and also joined the group.

Beatrice Webb and Sidney Webb worked on several books together including The History of Trade Unionism (1894) and Industrial Democracy (1897). The research that they carried out while writing these books convinced them there was a need to establish a new political party that was committed to obtaining socialism through parliamentary elections.

In 1894 Henry Hutchinson, a wealthy solicitor from Derby, left the Fabian Society £10,000. Beatrice and Sidney Webb suggested that the money should be used to develop a new university in London. The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) was founded in 1895. As Sidney Webb pointed out, the intention of the institution was to "teach political economy on more modern and more socialist lines than those on which it had been taught hitherto, and to serve at the same time as a school of higher commercial education".

The Webbs first approached Graham Wallas, a leading member of the Fabian Society, to become the Director of the LSE. Wallas declined the offer and W. A. S. Hewins, a young economist at Pembroke College, Oxford, was appointed instead. With the support of the London County Council (LCC) and the Technical Education Board, the LSE flourished as a centre of learning.

In 1898 the Webbs went on a year long research trip to North America, Australia and New Zealand. The Webbs main concern was to discover different approaches to local government. When they arrived home they carried out a study of the organization and function of English local government. Published in eleven volumes over a twenty-three year period, English Local Government, became the standard work on the subject. Beatrice wrote in her diary: "Are the books we have written together worth (to the community) the babies we might have had?"

On 27th February 1900, the Fabian Society joined with the Independent Labour Party, the Social Democratic Federation and trade union leaders to form the Labour Representation Committee(LRC). The LRC put up fifteen candidates in the 1900 General Election and between them they won 62,698 votes. Two of the candidates, Keir Hardie and Richard Bell won seats in the House of Commons.

Beatrice Webb was willing to work with any political party in order to obtain the policies she believed in. When the Conservative Party won the 1900 General Election, the Webbs drafted what later became the 1902 Education Act. The Webbs were strong critics of the Poor Law system in Britain. In 1905 the government established a Royal Commission to look into "the working of the laws relating to the relief of poor persons in the United Kingdom". Beatrice Webb was asked to serve as a member of the commission and her husband assisted with collecting the data on how the system was working. Beatrice disagreed with most of the members on the Royal Commission and together with Sidney Webb wrote and published a Minority Report. In their report the Webbs called for: (1) the end of the Poor Law; (2) the establishment and coordination of employment bureau throughout Britain to make efficient use of the nation's labour resources; (3) improving essential services such as education and health. The Liberal government headed by Herbert Asquith accepted the Majority Report and rejected the advice given by the Webbs.

In 1913 Beatrice Webb helped create the Fabian Research Department. During the same year the Webbs started a new political weekly, The New Statesman. Edited by Clifford Sharp with contributions from the Webbs, as well as from other members of the Fabian Society such as George Bernard Shaw, John Maynard Keynes and G. G. H. Cole, the journal promoted socialist reform of society.

During the First World War Beatrice Webb served on several government committees. She also wrote several Fabian Society pamphlets such as Labour and the New Social Order (1918), The Wages of Men and Women - Should They be Equal? (1919), Constitution for the Socialist Commonwealth of Great Britain (1920) and the Decay of Capitalist Civilization (1923).

In the 1923 General Election Beatrice's husband, Sidney Webb, was chosen to represent the Labour Party in the Seaham constituency. Webb won the seat and when Ramsay MacDonald became Britain's first Labour Prime Minister in 1924, he appointed Webb as his President of the Board of Trade.

Webb left the House of Commons in 1929 when he was granted the title Baron Passfield. Now in the House of Lords, Webb served as Secretary of State for the Colonies in MacDonald's second Labour Government. However, on a point of principle, Beatrice refused to accept the title of Lady Passfield.

In 1932 the Webbs visited the Soviet Union. Although unhappy with the lack of political freedom in the country they were impressed with the rapid improvement in the health and educational services and the changes that had taken place to ensure economic and political equality for women. When they returned to Britain they wrote a book on the economic experiments taking place in the Soviet Union called Soviet Communism: A New Civilization?(1935). In the book the Webbs predicted that "the social and economic system of planned production for community consumption" of the Soviet Union would eventually spread to the rest of the world. They added that they hoped this would happen through reform rather than revolution.

Despite the Stalinist Purges and the Nazi-Soviet Pact, the Webbs continued to support the Soviet economic experiment and in 1942 published The Truth About Soviet Russia (1942). Beatrice Webb died on 30th April, 1943.

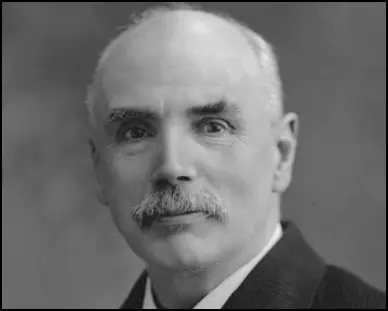

On this day in 1859 George Barnes was born at Lochee near Dundee on 2nd January 1859. His father, James Barnes, was a mechanic at a local textile mill but in 1866 the family moved to Liverpool and the following year settled in London.

George attended Enfield Church School for two years but at the age of eleven began work at a jute mill. In 1872 the Barnes family returned to Dundee and George found work at Parker's Foundry. When George completed his apprenticeship he moved to Barrow-in-Furness where he found work in the town's shipyard.

Unhappy with his wages of £3 a week, Barnes moved to London in 1879. After ten weeks unemployment he found temporary work and eventually obtained work constructing the Albert Dock in the Thames. Barnes was a maintenance engineer and gradually improved his skills by attending classes in engineering drawing and machine construction at Woolwich Arsenal.

In 1882 Barnes obtained better work at the Lucas & Airds in Fulham. Barnes joined the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (ASE) where he met Tom Mann and John Burns. Barnes attended meetings of the Social Democratic Federation and the Socialist League, but rejected the idea of socialist revolution and refused to join either organisation.

On the 13th February, 1887 Barnes attended the demonstration in Trafalgar Square that turned into the riot known as Bloody Sunday. Barnes was badly injured when he was trampled on by a police horse. However, two of his friends, John Burns and Robert Cunninghame Graham, were arrested and later sentenced to a six-week prison sentence.

In 1889 George Barnes was elected to the executive of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers. He supported the election of John Burns as general secretary of the union in 1890. Two years later Barnes was appointed as assistant general secretary.

Barnes worked closely with other socialist trade unionists and in 1893 joined with Keir Hardie, Robert Smillie, Tom Mann, John Glasier, H. H. Champion and Ben Tillett to form the Independent Labour Party (ILP). In the 1895 General Election the ILP put up 28 candidates but won only 44,325 votes. All the candidates were defeated, including George Barnes at Rochdale.

In 1896 Barnes became a full-time union official when he was elected as General Secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers. The ASE was now Britain third largest union and Barnes was one of the country's most powerful labour leaders. In July 1897 Barnes led the ASE in a long strike in an attempt to win an eight-hour day. The strike ended in January 1898 without this being achieved, but one success was the acceptance by the Employers Federation that it was willing to negotiate wages and conditions with the ASE.

Barnes went on a fact-finding mission in Europe in 1898. Although the trip convinced Barnes that British engineers were the best in Europe, he also discovered that Britain was falling behind other industrial nations in wage levels and working conditions. Barnes became convinced that real progress would only be made when more trade unionists were elected to the House of Commons.

Keir Hardie, the leader of the Independent Labour Party and George Bernard Shaw of the Fabian Society, believed that for socialists to win seats in parliamentary elections, it would be necessary to form a new party made up of various left-wing groups. On 27th February 1900, Barnes attended the meeting at the Congregational Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street, to discuss the future of the labour movement in Britain. Representatives of all the socialist groups in Britain and trade union leaders took part in the discussions. After a debate the 129 delegates decided to pass Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour."

To make this possible the Conference established a Labour Representation Committee (LRC). This committee included two members from the Independent Labour Party, two from the Social Democratic Federation, one member of the Fabian Society, and seven trade unionists. Barnes made a speech at the meeting arguing that not only working class men should be selected as LRC candidates in elections. He made the point that people like Frederic Harrison and Sidney Webb had important qualities to contribute to the labour movement. Barnes' motion was passed by 102 to 3.

In 1902 George Barnes formed the National Committee of Organised Labour for Old Age Pensions. Barnes spent the next three years travelling the country urging this social welfare reform. The measure was extremely popular and was an important factor in Barnes being able to defeat Andrew Bonar Law, the Conservative cabinet minister, in the 1906 General Election.

David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Liberal government led by Herbert Asquith was also an opponent of the Poor Law in Britain. He was determined to take action that in his words would "lift the shadow of the workhouse from the homes of the poor". In 1908 Lloyd George introduced the Old Age Pensions Act that provided between 1s. and 5s. a week to people over seventy. These pensions were only paid to citizens on incomes that were not over 12s.

Ramsay MacDonald argued that the Labour Party should fully support the budget. "Mr. Lloyd George's Budget, classified property into individual and social, incomes into earned and unearned, and followers more closely the theorical contentions of Socialism and sound economics than any previous Budget has done." Although Barnes welcomed Lloyd George's reforms, he argued that the level of benefits were far too low. They also complained that the pensions should be universal and disliked what was later to be called the Means Test aspect of these reforms.

By 1909 many Labour MPs, including George Barnes, objected to the strong support that the leadership was giving to the WSPU and the NUWSS in their fight for votes for women. Barnes argued that the party was being sidetracked from more important issues. James Keir Hardie was not very good with dealing with internal rivalries within the party, and in 1908 resigned from the post and Arthur Henderson became chairman. Henderson did not have the full-support of the party and in 1910 he decided to retire as chairman. Ramsay MacDonald was expected to become the new leader but recently his youngest son had died of diphtheria. Eight days later his mother also died. It was therefore decided that George Barnes should become chairman. A few months later Barnes wrote to MacDonald saying he did not want the chairmanship and was "only holding the fort". He continued, "I should say it is yours anytime".

Henderson also suggested that MacDonald should become chairman. As David Marquand, the author of Ramsay MacDonald (1977) pointed out: "It is unlikely that he did so out of a sudden access of personal affection, or even out of admiration for MacDonald's character and abilities. He wanted MacDonald as chairman, partly because he wanted to be party secretary himself and believed correctly that he would be a good one, partly because he believed - again correctly - that MacDonald was the only potential candidate capable of reconciling the ILP to the moderate line favoured by the unions."

The 1910 General Election saw 40 Labour MPs elected to the House of Commons. Two months later, on 6th February, 1911, Barnes sent a letter to the Labour Party announcing that he intended to resign as chairman. At the next meeting of MPs, Ramsay MacDonald was elected unopposed to replace Barnes. Arthur Henderson now became secretary. According to Philip Snowden, a bargin had been struck at the party conference the previous month, whereby MacDonald was to resign the secretaryship in Henderson's favour, in return for becoming chairman."

In 1914 George Barnes strongly supported Britain's involvement in the First World War. He toured industrial districts making recruitment speeches. Barnes also went to Canada where he helped to persuade trained mechanics to work in British industry. Barnes's youngest son, Henry, was killed fighting on the Western Front in September 1915. This did not change his views on the war and in 1916 was one of the few Labour MPs to support military conscription.

Barnes became disillusioned with the way Herbert Asquith was running the country and in 1916 helped David Lloyd George gain power. Lloyd George rewarded him by making George Barnes head of the recently formed Pensions Ministry.

At the end of the war the Labour Party withdrew from Lloyd George's coalition government. Barnes resigned from the party in order to remain as Minister of Pensions. He remained in the post until he resigned for reasons of poor health in January 1920.

Unable to gain the support from the Labour Party in the 1922 General Election, Barnes resigned from the House of Commons. Barnes travelled extensively for the next few years until he retired in 1927. George Barnes died on 21st April 1940.

On this day in 1867 Henria Williams, one of eight children of Henry Williams and Henria Leech Williams, was born in Oswestry, Shropshire. Her father worked as a Railway Signal Engineer and her mother was a governess and school mistress. Henry Williams later established a railway works in Cathcart, Glasgow.

The 1901 Census reveals that Henria Williams had moved to Buxton, Derbyshire, and was recorded as a "boarder living on her own means".Her widowed mother died in 1904, leaving a bequest which included stocks and shares in several railway companies and South African diamond mines. Her will stipulated that "money left to her daughters was to remain outside the control of any future husbands".

In 1905 Henria Williams moved to the village of Corbets Tey, Upminster, and purchased the "Cottage", which until recently had been the George Public House. "Her large home comprised an entrance hall, a drawing room with 'carved wood mantel & overmantel', a dining room, four bedrooms, an attic and cellar. Outside there were also glasshouses and a stable, while alongside, forming part of the property, was a newly-built two bedroom cottage, which was probably where her coachman lived."

Henria Williams became a passionate supporter of women's rights. On 9th July, 1909, she was arrested and held at Bow Street prison for breaking windows. Her brother commented: "The is a heroic spirit of the higher altruism which impels the most timid and retiring of men and women into action against a wrong. It is this spirit and animated... Henria Williams that inspires and sustains you in facing and hearing the persecution in combating a man made law which violated a moral law of creation.... We live and move on different planes of serfdom, inactivity, and nonentity, you are free women… That which I see as the saddest phase of the whole campaign is the devil-like treatment meted out to you, not by the manhood of the country, but by the few men in authority who, being themselves by nature both bullies and cowards, judge that by persecution and torture they will terrorize and drive you from your purpose." Henria became a "recognisable figure in the area, known for wearing a symbol of the suffragette movement on her clothing." Some of the villagers saw her as a "rather eccentric lady" and when in conversation "she poured forth a torrent of eloquence with great vivacity".

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. However, when Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, requested two hours to discuss the Conciliation Bill, H. H. Asquith made it clear that he intended to shelve it.

Emmeline Pankhurst was furious at what she saw as Asquith's betrayal and on 18th November, 1910, arranged to lead 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. Pankhurst and a small group of WSPU members, were allowed into the building but Asquith refused to see them. Women, in "detachments of twelve" marched forward but were attacked by the police.

Votes for Women reported that 159 women and three men were arrested during this demonstration. This included Henria Williams, Cecilia Wolseley Haig, Ada Wright, Catherine Marshall, Eveline Haverfield, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Mary Leigh, Vera Holme, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Kitty Marion, Gladys Evans, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, Clara Giveen, Eileen Casey, Patricia Woodcock, Vera Wentworth, Mary Clarke, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Minnie Turner, Lucy Burns and Grace Roe.

Sylvia Pankhurst later described what happened on what became known as Black Friday: "As, one after the other, small deputations of twelve women appeared in sight they were set upon by the police and hurled aside. Mrs Cobden Sanderson, who had been in the first deputation, was rudely seized and pressed against the wall by the police, who held her there by both arms for a considerable time, sneering and jeering at her meanwhile.... Just as this had been done, I saw Miss Ada Wright close to the entrance. Several police seized her, lifted her from the ground and flung her back into the crowd. A moment afterwards she appeared again, and I saw her running as fast as she could towards the House of Commons. A policeman struck her with all his force and she fell to the ground. For a moment there was a group of struggling men round the place where she lay, then she rose up, only to be flung down again immediately. Then a tall, grey-headed man with a silk hat was seen fighting to protect her; but three or four police seized hold of him and bundled him away. Then again, I saw Miss Ada Wright's tall, grey-clad figure, but over and over again she was flung to the ground, how often I cannot say. It was a painful and degrading sight. At last, she was lying against the wall of the House of Lords, close to the Strangers' Entrance, and a number of women, with pale and distressed faces were kneeling down round her. She was in a state of collapse."

Several women reported that the police dragged women down the side streets. "We knew this always meant greater ill-usage.... The police snatched the flags, tore them to shreds, and smashed the sticks, struck the women with fists and knees, knocked them down, some even kicked them, then dragged them up, carried them a few paces and flung them into the crowd of sightseers."

Henry Noel Brailsford wrote in Votes for Women: "Four witnesses described the barbarous usage to which another woman, Miss H. was subjected. After she had been flung to the ground, shaken and pushed, and had her arms and wrists twisted, she explained, "Help me to the railings". While trying to recover her breath, a policeman seized her head, and rubbed her face against the iron railings. To illustrate the recklessness with which the police seized women (usually by the throat) and flung them backwards to the ground, we would draw attention to two separate cases in which a woman was flung almost under the wheels of a passing motor car. The intention of terrorising and intimidating the women was carried by many of the police beyond mere violence. Twenty-nine of these statements complain of more or less aggravated acts of indency. Women describe such treatment only with the greatest reluctance, and though the volume of evidence under this head is a considerable, there are other instances which we are not permitted to cite."

Henria Williams was one of the women who was beaten by the police. She wrote to her friend, Dr. Jessie Murray about what happened. "I should first mention that I have a weak heart, and have not the physical power or breath to resist as my wish or spirit would will or like. Therefore, what may not seem extraordinary to some women or people was very much so for me. The police have such strong, large hands, that when they take hold of one by the throat, as I saw one man do - but not to me - or grab one's sides or ribs, which was done to me, they cannot possibly know how terribly at times they are hurting. One policeman after knocking me about for a considerable time, finally took hold of me with his great strong hand like iron just over my heart. He hurt me so much that at first I had not the voice power to tell him what he was doing. But I knew that unless I made a strong effort to do so he would kill me. So collecting all the power of my being, I commanded him to take his hand off my heart. Yet that policeman would not arrest me and he was the third or fourth who had knocked me about. The two first after pinching my arms, kicking my feet, and squeezing and hurting me in different ways, made me think that at last they had arrested me, but they each one only finally took me to the edge of the thick crowd, and then without mercy forced me into the midst of it, and with the crowd pushing in the opposite direction for a few minutes I doubted if I could keep my consciousness, and my breath had gone long before they finally left me in the crowd… Finally, I was so exhausted that I could not go out again with the last batch that same evening. Although I had no limbs broken, still my arms, sides, and ankles were sore for days afterwards. But that was not so bad as the inward shaking and exhaustion I felt."

Frank Whitty, a gentleman's outfitter from Sidcup, tried to rescue Henria Williams from the police: "I saw... sights that made me feel ashamed of my country; one of the cruelist cases was that of a brave lady... in a semi-fainting condition, so much so that she could hardly stand. Time after time, with a courage that should have shamed the police into doing their obvious duty and arresting her, she attempted to get through the cordon. I went to her side to do what I could to help and uphold her in her brave but hopeless struggle. At first I tried to persuade her to leave the crowd but .. realised her determination to "do or die" ... All I could do was to try and help her to the best of my power and to ward off the blows, kicks and insults as I could from her fainting body ... Time after time we were forced back into the crowd by the police with an amount of violence and brutality entirely unnecessary. On these occasions I had to put my arm around her to keep her from falling under the feet of the horses, or worse still, under the crowd.".

Henria Williams died on 2nd January 1911. Her brother wrote: "She died while actively engaged in furthering the cause which you have so deep at heart. From our long conversations and correspondence, it is beyond doubt that my sister was fully aware that she was affliction of the heart and the work she was doing was exceedingly dangerous. Nevertheless, she willingly and zealously persisted in doing whatever she could, and on several occasions expressed herself as quite prepared to make the sacrifice of some years of her natural life."

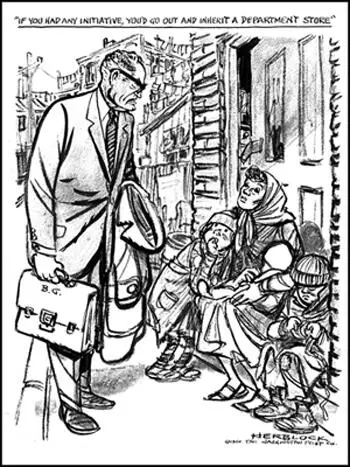

On this day in 1909 Barry Goldwater was born in Phoenix, Arizona on 1st January, 1909. His grandfather, a Polish immigrant, had established a large number of stores in Arizona in the 1870s. By the time Goldwater was born the family was extremely wealthy. Goldwater attended Staunton Military Academy and the University of Arizona, before joining the family department store business based in Phoenix.

After the death of his father in 1929, Goldwater played an important role in the development of the organization and in 1937 became head of the company. Goldwater was seen as a progressive employer and offered wages higher than the national retail-store average. The company also assumed the full cost of employees' health, accident, and life insurance. Other innovations included a profit-sharing plan and a maximum forty-hour week. Opposed to trade unions, Goldwater described his business strategy as "enlighten self-interest".

Goldwater found the strain of running such a large company difficult to take and had two nervous breakdowns in 1937 and 1939. Goldwater also started drinking heavily and made several unsuccessful attempts to give up alcohol.

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Goldwater joined the United States Air Force. Initially an instructor in the gunnery command, he later served overseas. By the time the war had finished in 1945, Goldwater had reached the rank of Brigadier General.

Goldwater had been an opponent of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. He also had a strong dislike of Harry S. Truman and his progressive social policies. Goldwater joined the Republican Party and in 1952 was elected to the Senate. He immediately became a loyal supporter of Joe McCarthy and was one of only 22 senators who voted against his censure in December, 1954. He later recalled: "The anti-anticommunists were outraged at his claims that some of the principals in the Truman and Roosevelt administrations actively served the communist causes... The liberals mounted a skillfully orchestrated campaign of criticism against Joe McCarthy. Under the pressure of criticism, he reacted angrily. It is probably true that McCarthy drank too much, overstated his case, and refused to compromise, but he wasn't alone in his beliefs."

On the extreme right of the Republican Party, Goldwater often criticised the policies of Dwight Eisenhower. He described his social policies as "dime-store New Deal" and strongly opposed the President's decision to use federal troops at Little Rock. Goldwater also believed that Eisenhower was too soft on trade unions and complained that his failure to balance the budget.

Goldwater expressed his conservative views in a syndicated newspaper column. A collection of these articles were published as The Conscience of the Conservative in 1960. Considered to be too right-wing to be a presidential candidate, Goldwater loyally supported Richard Nixon against John F. Kennedy in 1960.

As an opponent of federal civil rights laws Goldwater was highly critical of the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson. He also favoured a more aggressive approach to the Vietnam War. Nominated as the Republican Party as its presidential candidate in 1964, he upset many of his potential supporters by voting against Johnson's Anti-Poverty Act (1964).

His extreme anti-Communist views also frightened the American public. In one television interview Goldwalter explained that he would be willing to use nuclear weapons against communist forces in Vietnam. Although his views on civil rights made him popular in the Deep South, was easily defeated by Johnson by 42,328,350 votes to 26,640,178. Goldwater received 38.8 per cent of the vote and won only six states.

In 1968 Barry Goldwater won back his seat in the Senate. He supported the presidency of Richard Nixon but was critical of his attempt to control prices and wages. Goldwater loyally defended Nixon during the Watergate Scandal and it was not until 5th August, 1974, that he joined the campaign to have him impeached. Nixon now knew he could not survive and resigned from office four days later.

Goldwater continued in the Senate where he opposed the policies of Jimmy Carter but was an enthusiastic supporter of Ronald Reagan. In later life, Goldwater published two books, The Coming Breakpoint (1976) and his autobiography, With No Apologies (1979). Barry Goldwater died at Paradise Valley on 29th May, 1998.

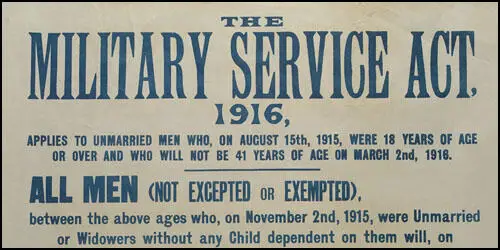

On this day in 1916 the government announces Military Service Bill. Over 3,000,000 men volunteered to serve in the British Armed Forces during the first two years of the war. Over 750,000 had enlisted by the end of September, 1914. Thereafter the average ran at 125,000 men a month until the summer of 1915 when numbers joining up began to slow down. Leo Amery, the MP for Birmingham Sparkbrook pointed out: "Every effort was made to whip up the flagging recruiting campaign. Immense sums were spent on covering all the walls and hoardings of the United Kingdom with posters, melodramatic, jocose or frankly commercial... The continuous urgency from above for better recruiting returns... led to an ever-increasing acceptance of men unfit for military work... Throughout 1915 the nominal totals of the Army were swelled by the maintenance of some 200,000 men absolutely useless for any conceivable military purpose."

The British had suffered high casualties at the Marne (12,733), Ypres (75,000), Gallipoli (205,000), Artois (50,000) and Loos (50,000). The British Army found it difficult to replace these men. In May 1915 135,000 men volunteered, but for August the figure was 95,000, and for September 71,000. Asquith appointed a Cabinet Committee to consider the recruitment problem. Testifying before the Committee, Lloyd George commented: "I would say that every man and woman was bound to render the services that the State they could best render. I do not believe you will go through this war without doing it in the end; in fact, I am perfectly certain that you will have to come to it."

The shortage of recruits became so bad that George V was asked to make an appeal: "At this grave moment in the struggle between my people and a highly-organized enemy, who has transgressed the laws of nations and changed the ordinance that binds civilized Europe together, I appeal to you. I rejoice in my Empire's effort, and I feel pride in the voluntary response from my subjects all over the world who have sacrificed home, fortune, and life itself, in order that another may not inherit the free Empire which their ancestors and mine have built. I ask you to make good these sacrifices. The end is not in sight. More men and yet more are wanted to keep my armies in the field, and through them to secure victory and enduring peace.... I ask you, men of all classes, to come forward voluntarily, and take your share in the fight".

Lord Northcliffe, the press baron, now began to advocate conscription (compulsory enrollment). On 16th August, 1915, the Daily Mail published a "Manifesto" in support of national service. The Conservative Party agreed with Lord Northcliffe about conscription but most members of the Liberal Party and the Labour Party were opposed to the idea on moral grounds. Some military leaders objected because they had a "low opinion of reluctant warriors".

C. P. Scott, the editor of The Manchester Guardian, was opposed to conscription, for practical reasons. He explained to Arthur Balfour: "You know that I was honestly willing to accept compulsory military service, provided that the voluntary system had first been tried out, and had failed to supply the men needed and who could still be spared from industry, and were numerically worth troubling about. Those, I think, are not unreasonable conditions, and I thought that in the conversation I had with you last September you agreed with them. I cannot feel that they had been fulfilled, and I do feel very strongly that compulsion is now being forced upon us without proof shown of its necessity, and I resent this the more deeply because it seems to me in the nature of a breach of faith with those who, like myself - there are plenty of them - were prepared to make great sacrifices of feeling and conviction in order to maintain the national unity and secure every condition needed for winning the war."

Margaret Bondfield was opposed to the idea as she thought it would influence the military tactics used in the war: "One of the great scandals of the First World War was the attitude of mind (an old one coming down from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) which regarded human life as the cheapest thing to expend. The whole war was fought on the principle of using up man-power. Tanks and similar mechanical help were received with hesitation and repugnance by commanders, and were inadequately used. But man-power, the lives of men, were used with freedom."

This view was expressed in a pamphlet published by the Independent Labour Party: "The armed forces of the nation have been multiplied at least five-fold since the war began, and recruits are still being enrolled well over 2,000,000 of its breadwinners to the new armies, and Lord Kitchener and Mr. Asquith have both repeatedly assured the public that the response to the appeal for recruits have been highly gratifying and has exceeded all expectations. What the conscriptionists want, however, is not recruits, but a system of conscription that will bring the whole male working-class population under the military control of the ruling classes."

H. H. Asquith, the prime minister, "did not oppose it on principle, though he was certainly not drawn to it temperamentally and had intellectual doubts about its necessity." Lloyd George had originally had doubts about the measure but by 1915 "he was convinced that the voluntary system of recruitment had served its turn and must give way to compulsion". Asquith told Maurice Hankey that he believed that "Lloyd George is out to break the government on conscription if he can."

Lloyd George threatened to resign if Asquith did not introduce conscription. Eventually he gave in and the Military Service Bill was introduced by Asquith on 21st January 1916. John Simon, the Home Secretary, resigned and so did Arthur Henderson, who had represented the Labour Party in the coalition government. Alfred George Gardiner, the editor of the Daily News argued that Lloyd George was engineering the conscription crisis in order to substitute himself for Asquith as leader of the country."

The Military Service Act specified that single men between the ages of 18 and 41 were liable to be called-up for military service unless they were widowed with children or ministers of religion. Conscription started on 2nd March 1916. The act was extended to married men on 25th May 1916. The law went through several changes before the war's end with the age limit eventually being raised to 51.

Lord Northcliffe received a large number of threatening letters because of his compulsion campaign. Tom Clarke, who worked for Northcliffe, saw the contents of these letters, commented that one said: "Warning to Lord Northcliffe... If the compulsion Bill is passed you are a dead man. I and another half-dozen young men have made a pledge - that is, to shoot you like a dog. We know where to find you."

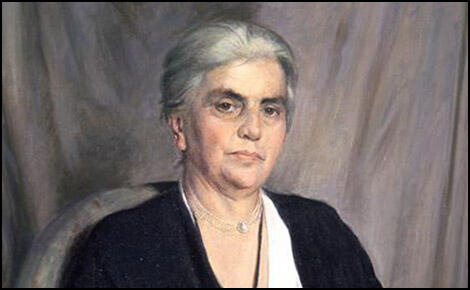

On this day in 1946 women's rights campaigner, Eleanor Rathbone, died of a heart-attack.

Eleanor Rathbone was born in London on 12th May 1872. Her father, William Rathbone, a prosperous shipowner, came from a Quaker and Unitarian background. A supporter of the Liberal Party, William Rathbone served in the House of Commons from 1869 to 1895.

Rathbone was educated at home by a governess and private tutors before entering Somerville College, Oxford, in 1893. At university Rathbone became involved in the struggle to obtain women the vote and eventually became a leading figure in the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).

After leaving university with a degree in philosophy, Rathbone became secretary of the Women's Industrial Council in Liverpool and was very involved in the organization's campaign against low pay and bad working conditions. In 1909 she became the first woman to be elected to Liverpool City Council and over the next few years argued for improved housing in the city.

Rathbone was elected to the executive committee of the NUWSS and led the opposition to the decision in 1912 to advise all members to campaign for the Labour Party in the general election. The following year she published her first book, The Condition of Widows under the Poor Law (1913).

During the First World War Rathbone established a committee to look into poverty in Britain. Members included Henry N. Brailsford, Maude Royden, Kathleen Courtney, Mary Stocks and Emile Burns. In 1917 the Family Endowment Committee published Equal Pay and the Family. A Proposal for the National Endowment of Motherhood (1917). In the pamphlet Rathbone and her colleagues argued for the introduction of family allowances.

On the resignation of Millicent Fawcett in March 1919, Rathbone became president of the National Union for Equal Citizenship. She continued to campaign for social reform and in 1925 published her important book, The Disinherited Family. The following year the introduction of family allowances became a policy of the Independent Labour Party. However, the idea was rejected by the three major political parties.

In 1929 Rathbone was elected to the House of Commons as the Independent Member for the Combined British Universities. Over the next few years she campaigned against female circumcision in Africa, child marriage in India and forced marriage in Palestine. This included the publication of the book, Child Marriage: The Indian Minotaur (1934).

Rathbone also took a keen interest in foreign policy and was a strong opponent of the Italian invasion of Ethiopia and non-intervention in the Spanish Civil War. In April 1937, Rathbone, Ellen Wilkinson and the Duchess of Atholl travelled to Spain on a fact-finding mission. The party visited Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia and observed the havoc being caused by the Luftwaffe.

In May 1937 Rathbone joined with Charlotte Haldane, Duchess of Atholl, Ellen Wilkinson and J. B. Priestley to establish the Dependents Aid Committee, an organization which raised money for the families of men who were members of the International Brigades. Later she helped establish the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief.

Rathbone grew increasingly concerned about Adolf Hitler and his government in Nazi Germany. She totally opposed the British government's policy of appeasement and instead called for an alliance with the Soviet Union. These views were expressed in her book, War Can Be Averted (1937) and were officially supported by Winston Churchill, Clement Attlee, David Lloyd George, Hugh Dalton and Margery Corbett-Ashby.

During the Second World War Rathbone continued to campaign for family allowances and in 1940 published The Case for Family Allowances. This became the policy of the Labour Party and her family allowances system was introduced in 1945. However, Rathbone was furious when she discovered that the allowance was to be paid to the father rather than the mother. This negated the feminist implications of the measure and she threatened to vote against the Bill.

Eleanor Rathbone died of a heart-attack on 2nd January 1946.

On this day in 1951 Edith New, militant suffragette died. Edith, one of five children of Isabella Frampton New, a music teacher, and Frederick James New, a railway clerk was born in Swindon on 17th March 1877. Her father was killed by a train in 1878..

In 1891, aged 14, she began working as a teacher. New was a supporter of women's suffrage and in 1906 she joined the Women's Social and Political Union. Established by Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, it had become frustrated by the lack of success by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).

New was one of those who believed that the WSPU should adopt more militant tactics. In January 1908 she chained herself to the railings of 10 Downing Street. During the summer of 1908 the WSPU introduced the tactic of breaking the windows of government buildings. On 30th June suffragettes marched into Downing Street and began throwing small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house. As a result of this demonstration, twenty-seven women, including Edith New and Mary Leigh, were arrested and and sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison.

When they were released from prison on 23rd August, they were greeted by a brass band and accorded a ceremonial welcome breakfast attended by the two main leaders of the WSPU, Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. After this Mary Leigh became the drum-major of the WSPU drum and fife band, which often accompanied their processions and demonstrations.

On 25th June 1909, Marion Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. On 5th July, 1909 she petitioned the governor of Holloway Prison: “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.”

Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her. According to Joseph Lennon: "She came to her prison cell as a militant suffragette, but also as a talented artist intent on challenging contemporary images of women. After she had fasted for ninety-one hours in London’s Holloway Prison, the Home Office ordered her unconditional release on July 8, 1909, as her health, already weak, began to fail".

On 22nd September 1909 Charlotte Marsh, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Leigh were arrested while disrupting a public meeting being held by Herbert Asquith. Marsh, Ainsworth and Leigh were all sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force.

The authorities believed that force-feeding would act as a deterrent as well as a punishment. This was a serious miscalculation and in many ways it had the opposite effect. Militant members of the WSPU now had beliefs as strong as any religion and now they could argue that women were actually being tortured for their faith. "Suffragettes submitted to force-feeding as a way to express solidarity with their friends as well as to further the cause." Edith New also adopted this approach and endured several hunger-strikes.

At a meeting in France, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us." Edith New also disagreed with this new policy and she left the WSPU and moved to Lewisham to resume her teaching career.