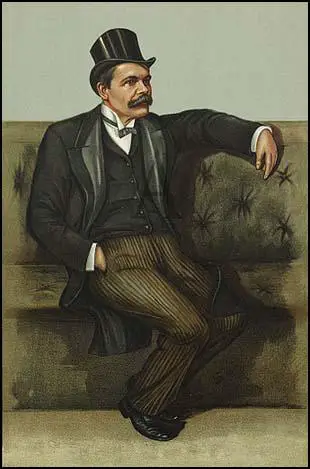

James Stuart

James Stuart, the eldest child of James Gordon Stuart, mill owner, and his wife, Catherine Booth, was born in Newburgh, Fife, on 2nd January, 1843. He had seven brothers, three of whom died in childhood, and one sister.

Stuart was educated at Madras College and at St Andrews University, where he graduated in 1861. The following year he won a scholarship to Trinity College and after graduation he became an assistant tutor at the University of Cambridge. After meeting Josephine Butler he became an advocate of women's education. In 1867 he gave a series of lectures for Butler's North of England Council for Promoting the Higher Education of Women and the London Society for the Extension of University Education.

His biographer, Colin Matthew, has argued: "He should not, as has sometimes been the case, be seen as sole originator of university extension, but he was certainly its most prominent early activist. In 1875 he was elected the first professor of mechanism and applied mechanics at Cambridge and planned the mechanical science tripos. Practical training cut across Cambridge's theoretical tradition, and Stuart's approach and his radical politics led to criticism."

Stuart, a member of the Liberal Party, developed a close relationship with Mary Gladstone, the daughter of William Ewart Gladstone, the prime minister. He encouraged Mary to read Progress and Poverty, a book by Henry George. Mary wrote in her diary that the book is "supposed to be the most upsetting, revolutionary book of the age. At present Maggie and I both agree with it, and most brilliantly written it is. We had long discussions. He (her father) is reading it too." Stuart told her: "The man (Henry George) is a true man, and that it would do one a great deal of good to spend a day or two with him. I, too, was pleased with his smashing of Malthus. I like to see anyone indignant and angry at any doctrine which makes misery and wrong a natural and inevitable and necessary consequence of the world's ordering." Her father was less impressed commenting "it is well-written but a wild book".

Susan K. Harris, the author of The Cultural Work of the Late Nineteenth-Century Hostess (2004) has argued: "One of the late nineteenth century's most influential works of political economy, Progress and Poverty (1879) attacks the premises of land ownership, rejecting Malthus and arguing that nationalization of rents would remedy all economic ills because the money accruing to the government would enable all other taxes to be repealed... In England, it fell into a vigorous British conversation about land, wages, taxes, and the nature of labour; a conversation that was being conducted on a number of levels, from radical Socialists, who loved the book, to landed aristocrats, who didn't. Everyone, however, recognized that this was a work with which it was necessary to contend, and most understood that it was one of the signal texts for trying to think through solutions to the gap between rich and poor that had manifested itself politically - especially through the Chartist movement - in mid-century, and had remained a source of anxiety for the privileged classes over the remainder of the century."

Stuart was also a strong supporter of women's suffrage and tried hard to convince Mary Gladstone of the need for reform. In March, 1884, Stuart replied to a letter he received from Mary. He suggested that female franchisement should follow lines already established by those municipalities that did allow women to vote: "To make women more independent of men is, I am convinced, one of the great fundamental means of bringing about justice, morality, and happiness both for married and unmarried men and women. If all Parliament were like the three men you mention, would there be no need for women's votes? Yes, I think there would. There is only one perfectly just, perfectly understanding Being - and that is God." He added: "No man is all-wise enough to select rightly - it is the people's voice thrust upon us, not elicited by us, that guides us rightly."

After unsuccessfully contesting Cambridge University Stuart was elected for Hackney in 1884. In the 1885 General Election he moved to the Hoxton constituency. Over the next few years he campaigned for women's suffrage and the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts and the reform of the House of Lords.

In 1890 Stuart married Laura Elizabeth, daughter of Jeremiah James Colman, the mustard manufacturer they had no children. When his father-in-law died unexpectedly in 1898, Stuart moved to Norfolk and managed the firm. Stuart was defeated in the 1900 General Election but was successful in Sunderland in the 1906 General Election. Stuart's radical political views meant that he was never offered a government post under William Ewart Gladstone, Henry Campbell-Bannerman or Herbert Asquith.

A profile of Stuart in Vanity Fair: "He is many-sided and too enthusiastic. He champions Women's Suffrage because, being a student of Exact Science, he cannot understand Woman. He has, indeed, championed more than one unpopular movement; though he is said to have more intimate knowledge of London political and social questions than anyone else. But he is a wicked Radical, whom the Water Companies hate, although he has friends among the Tories."

James Stuart died at his home, Carrow Abbey, Norwich, on 13th October 1913.

Primary Sources

(1) James Stuart, letter to Mary Gladstone (September, 1883)

The man (Henry George) is a true man, and that it would do one a great deal of good to spend a day or two with him. I, too, was pleased with his smashing of Malthus. I like to see anyone indignant and angry at any doctrine which makes misery and wrong a natural and inevitable and necessary consequence of the world's ordering.

(2) James Stuart, letter to Mary Gladstone (March, 1884)

To make women more independent of men is, I am convinced, one of the great fundamental means of bringing about justice, morality, and happiness both for married and unmarried men and women. If all Parliament were like the three men you mention, would there be no need for women's votes? Yes, I think there would. There is only one perfectly just, perfectly understanding Being - and that is God.... No man is all-wise enough to select rightly - it is the people's voice thrust upon us, not elicited by us, that guides us rightly.

(3) Vanity Fair (5th October, 1899)

He became a Fifeshire Scotchman six-and-fifty years ago; and having been doubly educated (at St. Andrews University and at Trinity, Cambridge) he fashioned himself into a Professor of Mechanics and Applied Mechanics. Then he tried to become Member for Cambridge University; but Cambridge University refusing the honour, he went to Hackney, which place he represented for precisely one year. Since then he has sat for the Hoxton Division of Shoreditch, while he lives in Grosvenor Road.

He neither shoots nor fishes, and he seldom takes a holiday; but he yachts, he cycles, he plays golf, and he sketches. He has also dabbled in journalism, being Chairman of the Board of The Star and Morning Leader Newspaper and Publishing Company, Limited. He is also the husband of the eldest daughter of Jeremiah James Colman: wherefore The Pall Mall Gazette once accused him of introducing mustard into The Star. He has done much to develop the pernicious system of University Extension; and his friends say that the most wonderful thing about him is how little he has been understood by the public. He is many-sided and too enthusiastic. He champions Women's Suffrage because, being a student of Exact Science, he cannot understand Woman. He has, indeed, championed more than one unpopular movement; though he is said to have more intimate knowledge of London political and social questions than anyone else. But he is a wicked Radical, whom the Water Companies hate, although he has friends among the Tories. He is a most tireless person of extraordinary physique, who can go all day without food; and though he can dine, he generally eats. Although he is a Professor he is neither a prude nor a pedant; and if it were not for his pernicious Politics he would be a good fellow.