On this day on 27th February

On this day in 1812 Lord Byron makes a speech in the House of Lords, in defence of the Luddites. "During the short time I recently passed in Nottingham, not twelve hours elapsed without some fresh act of violence; and on that day I left the the county I was informed that forty Frames had been broken the preceding evening, as usual, without resistance and without detection. Such was the state of that county, and such I have reason to believe it to be at this moment. But whilst these outrages must be admitted to exist to an alarming extent, it cannot be denied that they have arisen from circumstances of the most unparalleled distress: the perseverance of these miserable men in their proceedings, tends to prove that nothing but absolute want could have driven a large, and once honest and industrious, body of the people, into the commission of excesses so hazardous to themselves, their families, and the community."

Lord Byron went onto add: "They were not ashamed to beg, but there was none to relieve them: their own means of subsistence were cut off, all other employment preoccupied; and their excesses, however to be deplored and condemned, can hardly be subject to surprise. As the sword is the worst argument than can be used, so should it be the last. In this instance it has been the first; but providentially as yet only in the scabbard. The present measure will, indeed, pluck it from the sheath; yet had proper meetings been held in the earlier stages of these riots, had the grievances of these men and their masters (for they also had their grievances) been fairly weighed and justly examined, I do think that means might have been devised to restore these workmen to their avocations, and tranquillity to the country."

In 1812 Lord Byron spoke against the Frame Breaking Bill, by which the government intended to apply the death-penalty to Luddites. Byron's political views influenced the subject matter of his poems. Important examples include Song for the Luddites (1816) and The Landlords' Interest (1823). Byron also attacked his political opponents such as the Duke of Wellington and Lord Castlereagh in Wellington: The Best of the Cut-Throats (1819) and the The Intellectual Eunuch Castlereagh (1818).

On this day in 1869 Alice Hamilton is born in New York. According to Harriet Hyman Alonso: "Alice Hamilton, daughter of a wealthy entrepreneurial businessman in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and reared in a traditional Presbyterian family that valued philanthropy and education. Both her parents (particularly her mother) contributed great sums of money to community organizations, especially those addressing charity and the elimination of poverty. In addition, her mother was an early advocate of both temperance and woman suffrage, which introduced Hamilton to issues of concern to women."

Hamilton graduated from the University of Michigan Medical School in 1893. She served internships at hospitals in Minneapolis and Boston before studying bacteriology at the University of Leipzig and at the Johns Hopkins Medical School. In 1897, after graduate work in bacteriology and pathology, she accepted a position as professor of pathology and director of the histological and pathological laboratories at the Woman's Medical School at Northwestern University in Chicago.

After hearing a speech by Jane Addams she decided to join the Hull House settlement in the city. Other social reformers living at the settlement included Ellen Gates Starr, Alzina Stevens, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Florence Kelley, Julia Lathrop, and Sophonisba Breckinridge. Hamilton increasing became interested in social issues. In 1910 Charles S. Deneen, the governor of Illinois, appointed her to a commission to investigate occupational diseases. She studied industrial poisoning in the lead, rubber and munitions industries and was able to prove that lead, nitrous fumes and viscose rayon were causing serious side effects including mental illness, loss of vision, paralysis and in some cases, death. Hamilton used this evidence to pressurize politicians to pass workmen's compensation laws and factory owners to provide safer working conditions. Hamilton's research into the dangers of industrial pollution was also used in the campaign against child labour.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Hamilton and a group of women pacifists in the United States, began talking about the need to form an organization to help bring it to an end. On the 10th January, 1915, over 3,000 women attended a meeting in the ballroom of the New Willard Hotel in Washington and formed the Woman's Peace Party. Other women involved in the organization included Jane Addams, Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley, Anna Howard Shaw, Belle La Follette, Fanny Garrison Villard, Emily Balch, Jeanette Rankin, Lillian Wald, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Crystal Eastman, Carrie Chapman Catt, Emily Bach, and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

In April 1915, Arletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited members of the Woman's Peace Party to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Hamilton, Jane Addams, Grace Abbott and Emily Bachwere chosen to represent the United States. Others who went to the Hague included Lida Gustava Heymann (Germany); Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, (England); Chrystal Macmillan (Scotland) and Rosika Schwimmer (Hungary).

Alice Hamilton visited Germany in 1915. She later recalled: "One must always remember that most Germans read nothing and hear nothing from the outside. I talked with an old friend, the wife of a professor under whom I worked years ago when I was studying bacteriology in Germany. She and her husband are people with cosmopolitan connections, they read three languages beside their own, and have always been as far removed as possible from narrow provincialism, but since last July they have known nothing except what their Government has decided that they shall know. I did not argue with my friend, but, of course, we talked much together and after she had been with us for three days she told me that she had never known before that there were people in England who did not wish to crush Germany, who wished for a just settlement, and even some who were opposed to the war."

The women were attacked in the press by Theodore Roosevelt who described them as "hysterical pacifists" and called their proposals "both silly and base". Hamilton, along with Jane Addams, Florence Kelley, Alice Hamilton, Emily Balch, Mary Church Terrell, Jeanette Rankin and Lillian Wald attended the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom conference in Zurich in April, 1919. After the conference Hamilton and Addams made a tour of the Western Front.

Hamilton lived in Hull House for twenty-two years and thereafter returned for several months every year while Jane Addams was alive. In 1919 Hamilton became the first woman to be appointed to the staff at the Harvard Medical School. She also did studies on industrial pollution for the federal government and the United Nations. She also wrote several books including Industrial Poisons in the United States (1925), Industrial Toxicology (1934) and Exploring the Dangerous Trades (1943).

Hamilton was a member of the League of Women Voters, the Women's Trade Union League, the National Consumer's League, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. In 1927 Hamilton joined with John Dos Passos, Paul Kellogg, Jane Addams, Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Ben Shahn, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Floyd Dell, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells in an effort to prevent the execution of Nicola Sacco and Bertolomeo Vanzetti.

Even after Hamilton retired she continued to be active in politics and campaigned against McCarthyism, the execution of Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg, and the Vietnam War. At the age of eighty-eight Hamilton remarked that: "For me the satisfaction is that things are better now, and I had some part in it."

Alice Hamilton died on 22nd September, 1970, aged 101.

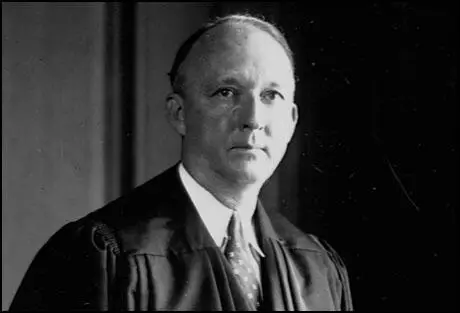

On this day in 1886 Hugo Black was born in Clay County, Alabama. After graduating from the University of Alabama in 1906 he practiced law in Birmingham.

A member of the Democratic Party, Black was elected to the Senate in 1926. Black had been influenced by the economic ideas of G.D.H. Cole and Stuart Chase. In December 1932 he introduced a bill to bar from interstate commerce articles produced in plant in which employees worked more than five days a week or six hours a day. Black claimed that his proposal would create six million jobs. William Green, the president of the American Federation of Labor, claimed the Black measure struck "at the root of the problem - technological unemployment" and threatened a national strike in support of the 30-hour week.

After he was elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt initially opposed massive public works spending. However, by the spring of 1933, the needs of more than fifteen million unemployed had overwhelmed the resources of local governments. In some areas, as many as 90 per cent of the people were on relief and it was clear something needed to be done. His close advisors and colleagues, Frances Perkins, Harry Hopkins, Rexford Tugwell, Robert LaFollette Jr. Robert Wagner, Fiorello LaGuardia, George Norris and Edward Costigan eventually won him over.

On 9th March 1933, Roosevelt called a special session of Congress. He told the members that unemployment could only be solved "by direct recruiting by the Government itself." For the next three months, Roosevelt proposed, and Congress passed, a series of important bills that attempted to deal with the problem of unemployment. The special session of Congress became known as the Hundred Days and provided the basis for Roosevelt's New Deal.

Black was also a strong supporter of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). At Muscle Shoals, Alabama, on the Tennessee River, a $145,000,000 hydro-electric plant and two munitions factories had been built during the First World War. After the war, Senator George Norris of Nebraska and John Rankin of Mississippi drafted a bill that would enable these facilities to be converted for peacetime purposes. Norris, a progressive Republican, twice persuaded Congress to pass this legislation, but both times it was vetoed by the president, first by Calvin Coolidge, and then by Herbert Hoover. They both argued that as the plant would be government owned, it would be an example of socialist planning. Something that both men were strongly against.

Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed with what Norris was trying to do and believing it would stimulate the economy of one of the poorest regions in the United States, gave it his full support. On 10th April, 1933, Roosevelt asked Congress to set up the Tennessee Valley Authority. The munitions factory became a chemical plant manufacturing fertilizers and the hydro-electric plant now generated power for parts of seven states (Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, Mississippi).

In 1937 Black was appointed to the Supreme Court. Members of the Republican Party in Congress objected because of his well-known support for the New Deal and it was claimed that Roosevelt was attempting to get a majority of justices who would not veto his legislation. Progressives in the Democratic Party were also uneasy about the appointment as Black had been for a long-time a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

As Republicans suspected, Hugo Black joined those on the Supreme Court who regarded Roosevelt's desire for increased federal powers over the economy as constitutional. However, he showed that he had clearly renounced his previous racial views and became a strong supporter of individual civil rights.

After the Second World War Black was clearly associated with the group of liberals on the Supreme Court that included Felix Frankfurter (1939-1962), William Douglas (1939-1975), Frank Murphy (1940-1949) and Thurgood Marshall (1967-1991). Over the years Black argued against mandatory school prayers and the need for the availability of legal counsel for suspected criminals. He also supported the right of newspapers such as the New York Times to expose the secret policies of Richard Nixon. Hugo Black died on 25th September, 1971.

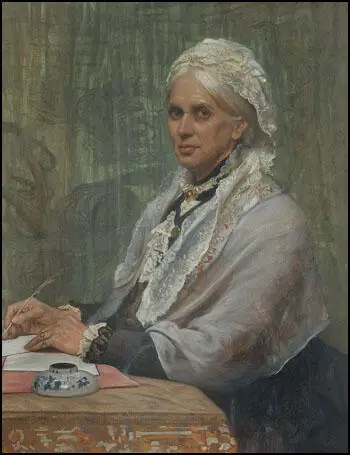

On this day 1892 Anne Jemima Clough, died. Anne, the daughter of James Clough and Anne Perfect, was born in Liverpool on 20th January 1820. Two years later the family moved to Charleston in South Carolina.

In 1836 the family returned to Liverpool where James Clough became a cotton merchant. The three sons were sent to private schools but Anne was educated at home by her mother. Anne was particularly close to her brother Arthur Hugh Clough. Arthur, had been taught by Thomas Arnold at Rugby and won a scholarship to Balliol College, Cambridge. Arthur, who was later to become professor of English Literature at University College, London, took a keen interest in Anne's education. He directed her studies and under his influence she began to visit and teach the poor.

After James Clough's business failed in 1841, Anne opened a small school in Liverpool to help pay off the family debts. The school opened in January 1842 but it attracted few children. Anne had doubts about her abilities as a teacher and in May 1843, wrote in her journal: "I fear I mismanage the children; however, I must try to do better."

In 1852 Anne moved to the village of Ambleside where she opened a school for the children of local farmers and trades people. Anne's school was popular and she soon had enough children to employ two other teachers.

Devastated by the death of her brother, Arthur Hugh Clough, Anne gave up the running of her school. However, Anne's achievements in Ambleside were well-known and in 1864 she was contacted by Emily Davies who was involved in the campaign to improve the quality of women's education. Encouraged by Davies, Clough wrote an article, Hints on the Organization of Girls' Schools for Macmillan's Magazine.

In 1865 Clough joined Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Helen Taylor and Elizabeth Garrett at meetings of the Kensington Society. After the failure of Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill in 1867 to persuade Parliament to give women the same political rights as men, the women formed the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Soon afterwards similar societies were formed in other large towns in Britain. Eventually seventeen of these groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.

Inspired by the success of the North London Collegiate School and Cheltenham Ladies College, Clough decided to form the North of England Council for Promoting the Higher Education of Women. The council held its first meeting at Leeds in 1867 and members included Josephine Butler, George Butler and Elizabeth Wolstenholme. Over the next few years the council developed a scheme of lectures and a university-based examination for women who wished to become teachers.

In 1871, Henry Sidgwick, who taught at Trinity College, established Newnham, a residence for women who were attending lectures at Cambridge University. Anne was invited to take charge and by 1879 Newnham College was fully established with its own tutorial staff.

As well as being principal of Newnham College, Anne Jemima Clough helped to establish the University Association of Assistant Mistresses (1882), the Cambridge Training College for Women (1885), and the Women's University Settlement in Southwark (1887).

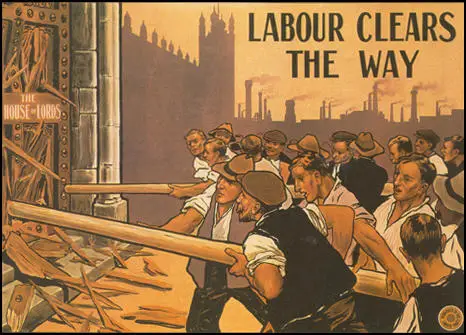

On this day in 1900 representatives of all the socialist groups in Britain (the Independent Labour Party (ILP), the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and the Fabian Society, met with trade union leaders at the Congregational Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street. After a debate the 129 delegates decided to pass Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." To make this possible the Conference established a Labour Representation Committee (LRC). The committee included two members from the ILP (Keir Hardie and James Parker), two from the SDF (Harry Quelch and James Macdonald), one member of the Fabian Society (Edward R. Pease), and seven trade unionists (Richard Bell, John Hodge, Pete Curran, Frederick Rogers, Thomas Greenall, Allen Gee and Alexander Wilkie). (11)

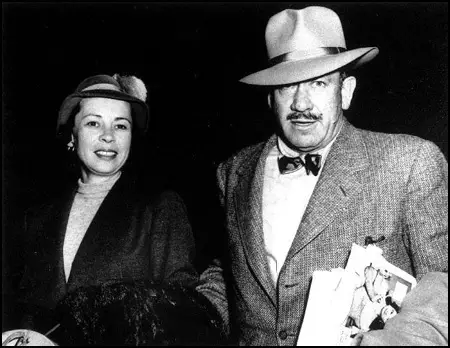

On this day in 1902 John Steinbeck, the son of John Ernst Steinbeck, was born in Sainas, California. His mother, Olive Hamilton Steinbeck, a former school teacher, encouraged her son's passion for reading and writing. He spent his summers working on nearby ranches with migrant workers. This gave him a great sympathy of the underdog.

Steinbeck studied marine biology at Stanford University in Palo Alto. In his spare-time he worked as a agricultural labourer while writing novels and in 1929 published Cup of Gold, based on the life and death of Henry Morgan. The following year he married Carol Henning. The couple lived in a cottage owned by his father in Pacific Grove. Steinbeck also spent time with the artistic community based in Carmel. This included Lincoln Steffens, Ella Winter, Albert Rhys Williams, Robinson Jeffers, Harry Leon Wilson and Marie de L. Welch. Winter described Steinbeck as "excessively shy, a red-faced, blue-eyed giant."

Steinbeck published a collection of short stories portraying the people in a farm community, The Pastures of Heaven (1932) and a novel about a farmer, To a God Unknown (1933). This was followed by Tortilla Flat (1935), that was set in nearby Monterey. With the proceeds of this novel he built a summer ranch-home in Los Gatos.

The journalist, Lincoln Steffens, was very impressed by his next novel, In Dubious Battle. He wrote to his friend, Sam Darcy on 25th February, 1936: "His novel is called In Dubious Battle, the story of a strike in an apple orchard. It's a stunning, straight, correct narrative about things as they happen. Steinbeck says it wasn't undertaken as a strike or labor tale and he was interested in some such theme as the psychology of a mob or strikers, but I think it is the best report of a labor struggle that has come out of this valley. It is as we saw it last summer. It may not be sympathetic with labor, but it is realistic about the vigilantes."

During this period Steinbeck showed great concern for those suffering from the Great Depression. In 1936 he wrote an article on the subject of the Dust Bowl: "Here, in the faces of the husband and his wife, you begin to see an expression you will notice on every face; not worry, but absolute terror of the starvation that crowds in against the borders of the camp.... This is a family of six; a man, his wife and four children. They live in a tent the colour of the ground. Rot has set in on the canvas so that the flaps and the sides hang in tatters and are held together with bits of rusty bailing wire. There is one bed in the family and that is a big tick lying on the ground inside the tent. They have one quilt and a piece of canvas for bedding. The sleeping arrangement is clever. Mother and father lie down together and two children lie between them. Then, heading the other way, the other two children lie, the littler ones."

Other books by Steinbeck included Of Mice and Men (1937), The Long Valley (1938) and his best-known novel, The Grapes of Wrath (1939). This novel of a family fleeing from the dust bowl of Oklahoma was made into a film directed by John Ford and featuring Henry Fonda, Jane Darwell, John Carradine, Shirley Mills, John Qualen and Eddie Quillan. The book also won Steinbeck the Pulitzer Prize in 1940.

John Steinbeck became estranged from Carol Henning in 1941 and they divorced the following year. He married Gwyndolyn Conger in 1942 and over the next few years the couple had two children Thomas Myles Steinbeck (1944) and John Steinbeck IV (1946 - 1991). He later married Elaine Scott, the former wife of Zachary Scott.

During the Second World War Steinbeck went to Europe where he reported the war for the New York Tribune. He also published The Moon is Down (1942), a novel about the resistance in Norway to the Nazi occupation. Steinbeck accompanied commando raids against German-held islands in the Mediterranean. In 1944, wounded by a close munitions explosion in North Africa.

Other books by Steinbeck include Cannery Row (1945), The Pearl (1947), A Russian Journal (1948), Burning Bright (1950), East of Eden (1952), Sweet Thursday (1954), The Short Reign of Pippin IV (1957) and a selection of his writings as a war correspondent, Once There Was a War (1958) and Winter of our Discount (1961).

John Steinbeck, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1962, died in New York City on 20th December, 1966, of heart disease and congestive heart failure. A lifelong smoker, an autopsy showed nearly complete occlusion of the main coronary arteries.

On this day in 1909 Mary Humphrey Ward publishes an article in The Times why women should not be allowed to vote. "Women's suffrage is a more dangerous leap in the dark than it was in the 1860s because of the vast growth of the Empire, the immense increase of England's imperial responsibilities, and therewith the increased complexity and risk of the problems which lie before our statesmen - constitutional, legal, financial, military, international problems - problems of men, only to be solved by the labour and special knowledge of men, and where the men who bear the burden ought to be left unhampered by the political inexperience of women."

In the summer of 1908 the famous author, Mary Humphry Ward, was approached by Lord Curzon and William Cremer and asked to become the first president of the Anti-Suffrage League. Ward agreed and on 8th July, 1908 the organisation published its manifesto. It included the following: "It is time that the women who are opposed to the concession of the parliamentary franchise to women should make themselves fully and widely heard. The matter is urgent. Unless those who hold that the success of the women's suffrage movement would bring disaster upon England are prepared to take immediate and effective action, judgement may go by default and our country drift towards a momentous revolution, both social and political, before it has realised the dangers involved."

Mary Humphry Ward argued the case against women's suffrage at debates at Newnham College and Girton College. Once a role model for educated young women, she received a hostile reception from the students when she told them that the "emancipating process has now reached the limits fixed by the physical constitution of women". She recorded in her diary after the Girton debate that "the fire and the rage were immense" and blamed the staff who she accused of being "hotly suffrage".

The Anti-Suffrage League collected signatures against women having the vote and at a meeting on 26th March, 1909, Mary Humphry Ward announced that over 250,000 people had signed the petition. The following June she reported that the movement had 15,000 paying members and 110 branches and the number who had signed the petition had reached 320,000.

On this day in 1917 Michael Rodzianko, President of the Duma warns Tsar Nicholas II about the possibility of revolution. "The situation is serious. The capital is in a state of anarchy. The government is paralyzed; the transport service has broken down; the food and fuel supplies are completely disorganized. Discontent is general and on the increase. There is wild shooting in the streets; troops are firing at each other. It is urgent that someone enjoying the confidence of the country be entrusted with the formation of a new government. There must be no delay. Hesitation is fatal."

On this day in 1933, Marinus van der Lubbe sets fire to the Reichstag. According to the first person who interviewed Marinus van der Lubbe he was "as silent as a wall" and that he was either "an idiot or one cool customer". Eventually the young Dutchman admitted that he had set fire to the Reichstag with firelighters and his own clothing. "The first fire went out. Then I lit my shirt on fire and carried it farther. I went through five rooms."

Van der Lubbe denied that he was part of a Communist conspiracy and had no connections with the Social Democratic Party (SDP) or German Communist Party (KPD). He insisted that he acted alone and the burning of the Reichstag was his own idea. He went on to claim, "I do nothing for other people, all for myself. No one was for setting the fire." However, he hoped that his act of arson would lead the revolution. "The workers should rebel against the state order. The workers should think that it is a symbol for a common uprising against the state order." (20) Hermann Göring, who was in control of the investigation, ignored what van der Lubbe had said and on 28th February, he made a statement stating that he had prevented a communist uprising.

On 3rd March, van der Lubbe made a full confession: "I myself am a Leftist, and was a member of the Communist Party until 1929. I had heard that a Communist demonstration was disbanded by the leaders on the approach of the police. In my opinion something absolutely had to be done in protest against this system. Since the workers would do nothing, I had to do something myself. I considered arson a suitable method. I did not wish to harm private people but something belonging to the system itself. I decided on the Reichstag. As to the question of whether I acted alone, I declare emphatically that this was the case."

On this day in 1939, Neville Chamberlain recognizes the fascist government headed by General Francisco Franco. In 1936 the Conservative government feared the spread of communism from the Soviet Union to the rest of Europe. Stanley Baldwin, the British prime minister, shared this concern and was fairly sympathetic to the military uprising in Spain against the left-wing Popular Front government.

Leon Blum, the prime minister of the Popular Front government in France, initially agreed to send aircraft and artillery to help the Republican Army in Spain. However, after coming under pressure from Stanley Baldwin and Anthony Eden in Britain, and more right-wing members of his own cabinet, he changed his mind.

Stanley Baldwin and Leon Blum now called for all countries in Europe not to intervene in the Spanish Civil War. In September 1936 a Non-Intervention Agreement was drawn-up and signed by 27 countries including Germany, Britain, France, the Soviet Union and Italy.

In the House of Commons on 29th October 1936, Clement Attlee, Philip Noel-Baker and Arthur Greenwood argued against the government policy of Non-Intervention. As Noel-Baker pointed out: "We protest with all our power against the sham, the hypocritical sham, that it now appears to be."

Benito Mussolini continued to give aid to General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist forces and during the first three months of the Nonintervention Agreement sent 90 Italian aircraft and refitted the cruiser Canaris, the largest ship in the Nationalists' fleet.

On 28th November the Italian government signed a secret treaty with the Spanish Nationalists. In return for military aid, the Nationalist agreed to allow Italy to establish bases in Spain in the case of a conflict with France. Over the next three months Mussolini sent to Spain 130 aircraft, 2,500 tons of bombs, 500 cannons, 700 mortars, 12,000 machine-guns, 50 whippet tanks and 3,800 motor vehicles.

Adolf Hitler also continued to give aid to General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist forces but attempted to disguise this by sending the men, planes, tanks, and munitions via Portugal. He also gave permission for the formation of the Condor Legion. The initial force consisted a Bomber Group of three squadrons of Ju-52 bombers; a Fighter Group with three squadrons of He-51 fighters; a Reconnaissance Group with two squadrons of He-99 and He-70 reconnaissance bombers; and a Seaplane Squadron of He-59 and He-60 floatplanes.

The Condor Legion, under the command of General Hugo Sperrle, was an autonomous unit responsible only to Franco. The legion would eventually total nearly 12,000 men. Sperrle demanded higher performance aircraft from Germany and he eventually received the Heinkel He111, Junkers Stuka and the Messerschmitt Bf109. It participated in all the major engagements including Brunete, Teruel, Aragon and Ebro.

The Labour Party originally supported the government's non-intervention policy. However, when it became clear that Hitler and Mussolini were determined to help the Nationalists win the war, Labour leaders began to call for Britain to supply the Popular Front with military aid. Some members of the party joined the International Brigades and fought for the Republicans in Spain.

When Neville Chamberlain replaced Stanley Baldwin as prime minister he continued the policy of nonintervention At the end of 1937 he took the controversial decision to send Sir Robert Hodgson to Burgos to be the British government's link with the Nationalist government.

On 18th January 1938, a letter was sent to The Manchester Guardian that was signed by Duchess of Atholl, John Haldane, George Strauss, Elizabeth Wilkinson, Margery Corbett-Ashby, Eileen Power, Richard Acland, Vernon Bartlett, Richard Stafford Cripps, Josiah Wedgwood, Victor Gollancz, Kingsley Martin, Violet Bonham Carter andR. H. Tawney. They argued: "It has now become clear that the Republicans are facing an overwhelming weight of arms, troops, and munitions accumulated by Italy and Germany in flagrant and open violation of their undertakings under the Non-Intervention Agreement...The embargoes must be lifted and the frontiers opened by Britain and France forthwith."

On 13th March 1938 Leon Blum returned to office in France. When he began to argue for an end to the country's nonintervention policy, Chamberlain and the Foreign Office joined with the right-wing press in France and political figures such as Henri-Philippe Petain and Maurice Gamelin to bring him down. On 10th April 1938, Blum was replaced by Edouard Daladier, a politician who agreed not only with Chamberlain's Spanish strategy but his appeasement policy.

Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden, encouraging the growth of fascism (c. 1938)