On this day on 12th February

On this day in 1809 Abraham Lincoln, the son of a farmer, was born born near Hodgenville, Kentucky, on 12th February, 1809. Although his parents were virtually illiterate, and he spent only a year at school, he developed a love of reading. In March 1830, the Lincoln family moved to Illinois.

After helping his father clear and fence his father's new farm, Lincoln moved to New Salem, where he worked as a storekeeper, postmaster and surveyor. He took a keen interest in politics and supported the Whig Party. In 1834 Lincoln was elected to the Illinois State Legislature where he argued that the role of federal government was to encourage business by establishing a national bank, imposing protective tariffs and improving the country's transport system.

In his spare time Lincoln continued his studies and became a lawyer after passing his bar examination in 1836. There was not much legal work in New Salem and the following year he moved to Springfield, the new state capital of Illinois.

In November, 1842, Lincoln married Mary Todd, the daughter of a prosperous family from Kentucky. The couple had four sons: Robert Lincoln (1843-1926), Edward Baker Lincoln (1846-50), William Lincoln (1850-62) and Thomas Lincoln (1853-1871). Three of the boys died young and only Robert lived long enough to marry and have children.

In 1844 Lincoln formed a legal partnership with William Herndon. The two men worked well together and shared similar political views. Herndon later claimed that he was instrumental in changing Lincoln's views on slavery.

Lincoln's continued to build up his legal work and in 1850 obtained the important role as the attorney for the Illinois Central Railroad. He also defended the son of a friend, William Duff Armstrong, who had been charged with murder. Lincoln successfully undermined the testimony of the prosecution's star witness, Charles Allen, and Armstrong was found not guilty.

In the Illinois State Legislature Lincoln spoke against slavery but believed that Southern states had the right to maintain their current system. When Elijah Lovejoy, an anti-slavery newspaperman was killed, Lincoln refused to condemn lynch-law and instead criticized the extreme policies of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

In 1856 Lincoln joined the Republican Party and challenged Stephen A. Douglas for his seat in the Senate. Lincoln was opposed to Douglas's proposal that the people living in the Louisiana Purchase (Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Iowa, the Dakotas, Montana, and parts of Minnesota, Colorado and Wyoming) should be allowed to own slaves. Lincoln argued that the territories must be kept free for "poor people to go and better their condition".

Lincoln raised the issue of slavery again in 1858 when he made a speech at Quincy, Illinois. Lincoln commented: "We have in this nation the element of domestic slavery. The Republican Party think it wrong - we think it is a moral, a social, and a political wrong. We think it is wrong not confining itself merely to the persons of the States where it exists, but that it is a wrong which in its tendency, to say the least, affects the existence of the whole nation. Because we think it wrong, we propose a course of policy that shall deal with it as a wrong. We deal with it as with any other wrong, insofar as we can prevent it growing any larger, and so deal with it that in the run of time there may be some promise of an end to it."

Lincoln's speech upset Southern slaveowners and poor whites, who valued the higher social status they enjoyed over slaves. However, with rapid European immigration taking place in the North, they knew they had a declining influence over federal government. Their concern turned into outrage when in 1860 the Republican Party nominated Lincoln as its presidential candidate. Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, a Radical Republican, was selected as his running mate.

The Democratic Party that met in Charleston in April, 1860, were deeply divided. Stephen A. Douglas was the choice of most northern Democrats but was opposed by those in the Deep South. When Douglas won the nomination, Southern delegates decided to hold another convention in Baltimore and in June selected John Beckenridge of Kentucky as their candidate. The situation was further complicated by the formation of the Constitutional Union Party and the nomination of John Bell of Tennessee as its presidential candidate.

Lincoln won the presidential election with with 1,866,462 votes (18 free states) and beat Stephen A. Douglas (1,375,157 - 1 slave state), John Beckenridge (847,953 - 13 slave states) and John Bell (589,581 - 3 slave states).

Lincoln selected his Cabinet carefully as he knew he would need a united government to face the serious problems ahead. His team included William Seward (Secretary of State), Salmon Chase (Secretary of the Treasury), Simon Cameron (Secretary of War), Gideon Welles (Secretary of the Navy), Edward Bates (Attorney General), Caleb Smith (Secretary of the Interior) and Montgomery Blair (Postmaster General).

During his first administration he made only five changes to his Cabinet: Edwin M. Stanton (Secretary of War - 1862), John Usher (Secretary of the Interior - 1863), William Fessenden (Secretary of the Treasury - 1864), James Speed (Attorney General - 1864), William Dennison (Postmaster General - 1864), Henry McCulloch (Secretary of the Treasury - 1865) and James Harlan (Secretary of the Interior - 1865).

In the three months that followed the election of Lincoln, seven states seceded from the Union: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas. Representatives from these seven states quickly established a new political organization, the Confederate States of America.

On 8th February the Confederate States of America adopted a constitution and within ten days had elected Jefferson Davis as its president and Alexander Stephens, as vice-president. Montgomery, Alabama, became its capital and the Stars and Bars was adopted as its flag. Davis was also authorized to raise 100,000 troops.

At his inaugural address, Abraham Lincoln attempted to avoid conflict by announcing that he had no intention "to interfere with the institution of slavery in the states where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so." He added: "The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without yourselves being the aggressors."

President Jefferson Davis took the view that after a state seceded, federal forts became the property of the state. On 12th April, 1861, General Pierre T. Beauregard demanded that Major Robert Anderson surrender Fort Sumter in Charleston harbour. Anderson replied that he would be willing to leave the fort in two days when his supplies were exhausted. Beauregard rejected this offer and ordered his Confederate troops to open fire. After 34 hours of bombardment the fort was severely damaged and Anderson was forced to surrender.

On hearing the news Lincoln called a special session of Congress and proclaimed a blockade of Gulf of Mexico ports. This strategy was based on the Anaconda Plan developed by General Winfield Scott, the commanding general of the Union Army. It involved the army occupying the line of the Mississippi and blockading Confederate ports. Scott believed if this was done successfully the South would negotiate a peace deal. However, at the start of the war, the US Navy, had only a small number of ships and was in no position to guard all 3,000 miles of Southern coast.

On 15th April, 1861, Lincoln called on the governors of the Northern states to provide 75,000 militia to serve for three months to put down the insurrection. Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas and Tennessee, all refused to send troops and joined the Confederacy. Kentucky and Missouri were also unwilling to supply men for the Union Army but decided not to take sides in the conflict.

Some states responded well to Lincoln's call for volunteers. The governor of Pennsylvania offered 25 regiments, whereas Ohio provided 22. Most men were encouraged to enlist by bounties offered by the state governments. This money attracted the poor and the unemployed. Many black Americans also attempted to join the army. However, the War Department quickly announced that it had "no intention to call into service of the Government any coloured soldiers." Instead, black volunteers were given jobs as camp attendants, waiters and cooks.

General Winfield Scott was seventy-five when the Civil War started so Lincoln persuaded him to retire and appointed General Irvin McDowell as head of the Union Army. Lincoln sent McDowell to take Richmond, the new base the Confederate government. On 21st July McDowell engaged the Confederate Army at Bull Run. The Confederate troops led by Joseph E. Johnston, Thomas Stonewall Jackson, James Jeb Stuart and Pierre T. Beauregard, easily defeated the inexperienced soldiers of the Union Army. The South had won the first great battle of the war and the Northern casualties totaled 1,492 with another 1,216 missing.

On 30th August, 1861, Major General John C. Fremont, commander of the Union Army in St. Louis, proclaimed that all slaves owned by Confederates in Missouri were free. Lincoln was furious when he heard the news as he feared that this action would force slave-owners in border states to join the Confederate Army. Lincoln asked Fremont to modify his order and free only slaves owned by Missourians actively working for the South. When Fremont refused, he was sacked and replaced by the more conservative, General Henry Halleck.

In November, 1861, Lincoln decided to appoint George McClellan, who was only 34 years old, as commander in chief of the Union Army. He developed a strategy to defeat the Confederate Army that included an army of 273,000 men. His plan was to invade Virginia from the sea and to seize Richmond and the other major cities in the South. McClellan believed that to keep resistance to a minimum, it should be made clear that the Union forces would not interfere with slavery and would help put down any slave insurrections.

In January 1862 the Union Army began to push the Confederates southward. The following month Ulysses S. Grant took his army along the Tennessee River with a flotilla of gunboats and captured Fort Henry. This broke the communications of the extended Confederate line and Joseph E. Johnston decided to withdraw his main army to Nashville. He left 15,000 men to protect Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River but this was enough and Grant had no difficulty taking this prize as well. With western Tennessee now secured, Lincoln was now able to set up a Union government in Nashville by appointing Andrew Johnson as its new governor.

George McClellan appointed Allan Pinkerton to employ his agents to spy on the Confederate Army. His reports exaggerated the size of the enemy and McClellan was unwilling to launch an attack until he had more soldiers available. Under pressure from Radical Republicans in Congress, Abraham Lincoln decided in January, 1862, to appoint Edwin M. Stanton as his new Secretary of War.

Soon after this Lincoln ordered George McClellan to appear before a committee investigating the way the war was being fought. On 15th January, 1862, McClellan had to face the hostile questioning of Benjamin Wade and Zachariah Chandler. Wade asked McClellan why he was refusing to attack the Confederate Army. He replied that he had to prepare the proper routes of retreat. Chandler then said: "General McClellan, if I understand you correctly, before you strike at the rebels you want to be sure of plenty of room so that you can run in case they strike back." Wade added "Or in case you get scared". After McClellan left the room, Wade and Chandler came to the conclusion that McClellan was guilty of "infernal, unmitigated cowardice".

As a result of this meeting Lincoln decided he must find a way to force George McClellan into action. On 31st January he issued General War Order Number One. This ordered McClellan to begin the offensive against the enemy before the 22nd February. Lincoln also insisted on being consulted about McClellan's military plans. Lincoln disagreed with McClellan's desire to attack Richmond from the east. Lincoln only gave in when the division commanders voted 8 to 4 in favour of McClellan's strategy. However, Lincoln no longer had confidence in McClellan and removed him from supreme command of the Union Army. He also insisted that McClellan left 30,000 men behind to defend Washington.

In May, 1862 General David Hunter began enlisting black soldiers in the occupied districts of South Carolina. He was ordered to disband the 1st South Carolina (African Descent) but eventually got approval from Congress for his action. Hunter also issued a statement that all slaves owned by Confederates in the area were free. Lincoln quickly ordered Hunter to retract his proclamation as he still feared that this action would force slave-owners in border states to join the Confederates.

Radical Republicans were furious and John Andrew, the governor of Massachusetts, said that "from the day our government turned its back on the proclamation of General Hunter, the blessing of God has been withdrawn from our arms." The actions of General David Hunter and Lincoln's reaction stimulated a discussion on the recruitment of black soldiers in the Northern press. Wendell Phillips asked, "How many times are we to save Kentucky and lose the war?" This debate was also taking place in the Cabinet, as Edwin M. Stanton was now advocating the creation of black regiments in the Union Army.

Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, one of the leaders of the anti-slavery movement, urged Lincoln to "convert the war into a war on slavery". Lincoln replied that he would continue to place the Union ahead of all else. "My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it; and if I could do it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that."

During the summer of 1862, George McClellan and the Army of the Potomac, took part in what became known as the Peninsular Campaign. The main objective was to capture Richmond, the base of the Confederate government. McClellan and his 115,000 troops encountered the Confederate Army at Williamsburg on 5th May. After a brief battle the Confederate forces retreated South.

McClellan moved his troops into the Shenandoah Valley and along with John C. Fremont, Irvin McDowell and Nathaniel Banks surrounded Thomas Stonewall Jackson and his 17,000 man army. First Jackson attacked John C. Fremont at Cross Keys before turning on Irvin McDowell at Port Republic. Jackson then rushed his troops east to join up with Joseph E. Johnson and the Confederate forces fighting McClellan.

General Joseph E. Johnston with some 41,800 men counter-attacked McClellan's slightly larger army at Fair Oaks. The Union Army lost 5,031 men and the Confederate Army 6,134. Johnson was badly wounded during the battle and General Robert E. Lee now took command of the Confederate forces.

Major General John Pope, the commander of the new Army of Virginia, was instructed to move east to Blue Ridge Mountains towards Charlottesville. It was hoped that this move would help McClellan by drawing Robert E. Lee away from defending Richmond. Lee's 80,000 troops were now faced with the prospect of fighting two large armies: McClellan (90,000) and Pope (50,000)

Joined by Thomas Stonewall Jackson, the Confederate troops constantly attacked McClellan and on 27th June they broke through at Gaines Mill. Convinced he was outnumbered, McClellan retreated to James River. Lincoln, frustrated by McClellan's lack of success, sent in Major General John Pope, but he was easily beaten back by Jackson.

George McClellan wrote to Abraham Lincoln complaining that a lack of resources was making it impossible to defeat the Confederate forces. He also made it clear that he was unwilling to employ tactics that would result in heavy casualties. He claimed that "ever poor fellow that is killed or wounded almost haunts me!" On 1st July, 1862, McClellan and Lincoln met at Harrison Landing. McClellan once again insisted that the war should be waged against the Confederate Army and not slavery.

Salmon Chase (Secretary of the Treasury), Edwin M. Stanton (Secretary of War) and vice president Hannibal Hamlin, who were all strong opponents of slavery, led the campaign to have George McClellan sacked. Unwilling to do this, Abraham Lincoln decided to put McClellan in charge of all forces in the Washington area.

George McClellan became a field commander again when the Confederate Army invaded Maryland in September. McClellan and Major General Ambrose Burnside attacked the armies of Robert E. Lee and Thomas Stonewall Jackson at Antietam on 17th September. Outnumbered, Lee and Jackson held out until Ambrose Hill and reinforcements arrived. It was the most costly day of the war with the Union Army having 2,108 killed, 9,549 wounded and 753 missing.

Although far from an overwhelming victory, Lincoln realized the significance of Antietam and on 22nd September, 1862, he felt strong enough to issue his Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln told the nation that from the 1st January, 1863, all slaves in states or parts of states, still in rebellion, would be freed. However, to keep the support of the conservatives in the government, this proclamation did not apply to those border slave states such as Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri that had remained loyal to the Union.

Lincoln now wanted George McClellan to go on the offensive against the Confederate Army. However, McClellan refused to move, complaining that he needed fresh horses. Radical Republicans now began to openly question McClellan's loyalty. "Could the commander be loyal who had opposed all previous forward movements, and only made this advance after the enemy had been evacuated" wrote George W. Julian. Whereas William P. Fessenden came to the conclusion that McClellan was "utterly unfit for his position".

Frustrated by McClellan unwillingness to attack, Lincoln recalled him to to Washington with the words: "My dear McClellan: If you don't want to use the Army I should like to borrow it for a while." On 7th November Lincoln removed McClellan from all commands and replaced him with Ambrose Burnside.

In January 1863 it was clear that state governors in the north could not raise enough troops for the Union Army. On 3rd March, the federal government passed the Enrollment Act. This was the first example of conscription or compulsory military service in United States history. The decision to allow men to avoid the draft by paying $300 to hire a substitute, resulted in the accusation that this was a rich man's war and a poor man's fight.

Lincoln was also now ready to give his approval to the formation of black regiments. He had objected in May, 1862, when General David Hunter began enlisting black soldiers into the 1st South Carolina (African Descent) regiment. However, nothing was said when Hunter created two more black regiments in 1863 and soon afterwards Lincoln began encouraging governors and generals to enlist freed slaves.

John Andrew, the governor of Massachusetts, and a passionate opponent of slavery, began recruiting black soldiers and established the 5th Massachusetts (Colored) Cavalry Regiment and the 54th Massachusetts (Colored) and the 55th Massachusetts (Colored) Infantry Regiments. In all, six regiments of US Colored Cavalry, eleven regiments and four companies of US Colored Heavy Artillery, ten batteries of the US Colored Light Artillery, and 100 regiments and sixteen companies of US Colored Infantry were raised during the war. By the end of the conflict nearly 190,000 black soldiers and sailors had served in the Union forces.

In December, 1862, Ambrose Burnside, commander of the Army of the Potomac, attacked General Robert E. Lee at Fredericksburg, Virginia. Sharpshooters based in the town initially delayed the Union Army from building a pontoon bridge across the Rappahnnock River. After clearing out the snipers the federal forces had the problem of mounting frontal assaults against troops commanded by James Longstreet. At the end of the day the Union Army had 12,700 men killed or wounded. The well protected Confederate Army suffered losses of 5,300. Ambrose Burnside wanted to renew the attack the following morning but was talked out of it by his commanders.

After the disastrous battle at Fredericksburg Burnside was replaced by Joseph Hooker. Three months later Hooker, with over 104,000 men, began to move towards the Confederate Army. In April, 1863, Hooker decided to attack the Army of Northern Virginia that had been entrenched on the south side of the Rappahonnock River. Hooker crossed the river and took up position at Chancellorsville.

Although outnumbered two to one, Robert E. Lee, opted to split his Confederate Army into two groups. Lee left 10,000 men under Jubal Early, while he and Thomas Stonewall Jackson on 2nd May, successfully attacked the flank of Hooker's army. However, after returning from the battlefield Jackson was accidentally shot by one of his own men. Jackson's left arm was successfully amputated but he developed pneumonia and he died eight days later.

On the 3rd May, James Jeb Stuart, who had taken command of Jackson's troops, mounted another attack and drove Hooker back further. The following day Robert E. Lee and Jubal Early and joined the attack on the Union Army. By 6th May, Hooker had lost over 11,000 men, and decided to retreat from the area.

Later that month Joseph E. Johnston ordered General John Pemberton to attack Ulysses S. Grant at Clinton, Mississippi. Considering this too risky, Pemberton decided to attack Grant's supply train on the road between Grand Gulf and Raymond. Discovering Pemberton's plans, Grant attacked the Confederate Army at Champion's Hill. Pemberton was badly defeated and with the remains of his army returned to their fortifications around Vicksburg. After two failed assaults, Grant decided to starve Pemberton out. This strategy proved successful and on 4th July, Pemberton surrendered the city. The western Confederacy was now completely isolated from the eastern Confederacy and the Union Army had total control of the Mississippi River.

During the summer of 1863 Robert E. Lee decided to take the war to the north. The Confederate Army reached Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on 1st July. The town was quickly taken but the Union Army, led by Major General George Meade, arrived in force soon afterwards and for the next two days the town was the scene of bitter fighting. Attacks led by James Jeb Stuart and James Longstreet proved costly and by the 5th July, Lee decided to retreat south. Both sides suffered heavy losses with Lee losing 28,063 men and Meade 23,049.

Lincoln was encouraged by the army's victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg, but was dismayed by the news of the Draft Riots in several American cities. There was heavy loss of life in Detroit but the worst rioting took place in New York City in July. The mob set fire to an African American church and orphanage, and attacked the office of the New York Tribune. Started by Irish immigrants, the main victims were African Americans and activists in the anti-slavery movement. The Union Army were sent in and had to open fire on the rioters in order to gain control of the city. By the time the riot was over, nearly a 1,000 people had been killed or wounded.

In September, 1863, General Braxton Bragg and his troops attacked union armies led by George H. Thomas and William Rosecrans at Chickamuga. Thomas was able to hold firm but Rosecrans and his men fled to Chattanooga. Bragg followed and was attempting to starve Rosecrans out when union forces led by Ulysses S. Grant, Joseph Hooker and William Sherman arrived. Bragg was now forced to retreat and did not stop until he reached Dalton, Georgia.

Major General George Meade also followed the army of Robert E. Lee back south. Lee ordered several counter-attacks but was unable to prevent the Union Army advance taking place. Lee decided to dig in along the west bank of the Mine Run. Considering the fortifications too strong, Meade decided against an assault and spent the winter on the north bank of the Rapidan.

In March, 1864, Ulysses S. Grant was named lieutenant general and the commander of the Union Army. He joined the Army of the Potomac where he worked with George Meade and Philip Sheridan. They crossed the Rapidan and entered the Wilderness. When Lee heard the news he sent in his troops, hoping that the Union's superior artillery and cavalry would be offset by the heavy underbrush of the Wilderness. Fighting began on the 5th May and two days later smoldering paper cartridges set fire to dry leaves and around 200 wounded men were either suffocated or burned to death. Of the 88,892 men that Grant took into the Wilderness, 14,283 were casualties and 3,383 were reported missing. Robert E. Lee lost 7,750 men during the fighting.

On 7th May Ulysses S. Grant gave William Sherman the task of destroying the Confederate Army in Tennessee. Joseph E. Johnston and his army retreated and after some brief skirmishes the two sides fought at Resaca (14th May), Adairsvile (17th May), New Hope Church (25th May) the Kennesaw Mountain (27th June) and Marietta (2nd July). President Jefferson Davis was unhappy about Johnson's withdrawal policy and on 17th July replaced him with the more aggressive John Hood. He immediately went on the attack and hit George H. Thomas and his men at Peachtree Creek. He was badly beaten and lost 2,500 men. Two days later he took on William Sherman at the Battle of Atlanta and lost another 8,000 men.

Attempts to clear out the Shenandoah Valley by Major General Franz Sigel in May and Major General David Hunter in June, ended in failure. Major General Jubal Early, who defeated Hunter, was sent north with 14,000 men in an attempt to draw off troops from Grant's army. Major General Lew Wallace encountered Early by the Monacacy River and although defeated was able to slow his advance to Washington. His attempts to breakthrough the ring forts around the city ended in failure. Lincoln, who witnessed the attack from Fort Stevens, became the first president in American history to see action while in office.

In the summer of 1864 the supporters of the Union became more confident they would win the war. Politicians began to debate what should happen to the South after the war. Radical Republicans were worried that Lincoln would be too lenient on the supporters of the Confederacy. Benjamin Wade and Henry Winter Davis decided to sponsored a bill that provided for the administration of the affairs of southern states by provisional governors. They argued that civil government should only be re-established when half of the male white citizens took an oath of loyalty to the Union.

The Wade-Davis Bill was passed on 2nd July, 1864, with only one Republican voting against it. However, Lincoln refused to sign it. Lincoln defended his decision by telling Zachariah Chandler, one of the bill's supporters, that it was a question of time: "this bill was placed before me a few minutes before Congress adjourns. It is a matter of too much importance to be swallowed in that way." Six days later Lincoln issued a proclamation explaining his views on the bill. He argued that he had rejected it because he did not wish "to be inflexibly committed to any single plan of restoration".

The Radical Republicans were furious with Lincoln's decision. On 5th August, Benjamin Wade and Henry Winter Davis published an attack on Lincoln in the New York Tribune. In what became known as the Wade-Davis Manifesto, the men argued that Lincoln's actions had been taken "at the dictation of his personal ambition" and accused him of "dictatorial usurpation". They added that: "he must realize that our support is of a cause and not of a man."

In August, 1864, the Union Army made another attempt to take control of the Shenandoah Valley. Philip Sheridan and 40,000 soldiers entered the valley and soon encountered troops led by Jubal Early who had just returned from Washington. After a series of minor defeats, Sheridan eventually gained the upper hand. Grant now burnt and destroyed anything of value in the area and after defeating Early in another large-scale battle on 19th October, the Union Army took control of the Shenandoah Valley.

With the South on the verge of defeat, growing number of politicians in the North began to criticize Lincoln for not negotiating a peace deal with Jefferson Davis. Even former supporters such as Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, accused him of prolonging the war to satisfy his personal ambition. Others on the right, such as Clement Vallandigham, claimed that Lincoln was waging a "wicked war in order to free the slaves". Other critics such as Fernando Wood, the mayor of New York, advocated that if Lincoln did not change his policies the city should secede from the Union.

Leading members of the Republican Party began to suggest that Lincoln should replace Hannibal Hamlin as his running mate in the 1864 presidential election. Hamlin was a Radical Republican and it was felt that Lincoln was already sure to gain the support of this political group. It was argued that what Lincoln needed was the votes of those who had previously supported the Democratic Party in the North.

Lincoln's original choice as his vice-president was General Benjamin Butler. Butler, a war hero, had been a member of the Democratic Party, but his experiences during the American Civil War had made him increasingly radical. Simon Cameron was sent to talk to Butler at Fort Monroe about joining the campaign. However, Butler rejected the offer, jokingly saying that he would only accept if Lincoln promised "that within three months after his inauguration he would die".

It was now decided that Andrew Johnson, the governor of Tennessee, would make the best candidate for vice president. By choosing the governor of Tennessee, Lincoln would emphasis that Southern states status were still part of the Union. He would also gain the support of the large War Democrat faction. At a convention of the Republican Party on 8th July, 1864, Johnson received 200 votes to Hamlin's 150 and became Lincoln's running mate. This upset Radical Republications as Johnson had previously made it clear that he was a supporter of slavery.

The military victories of Ulysses S. Grant, William Sherman, George Meade, Philip Sheridan and George H. Thomas in the American Civil War reinforced the idea that the Union Army was close to bringing the war to an end. This helped Lincoln's presidential campaign and with 2,216,067 votes, comfortably beat General George McClellan (1,808,725) in the election.

By the beginning of 1865, Fort Fisher, North Carolina, was the last port under the control of the Confederate Army. Fort Fisher fell to a combined effort of the Union Army and the US Navy on 15th January. William Sherman, removed all resistance in the Shenandoah Valley and then marched to Southern Carolina. On 17th February, Columbia, the capital of South Carolina, was taken. Columbia was virtually burnt to the ground and some people claimed the damage was done by Sherman's men and others said it was carried out by the retreating Confederate Army.

In March, 1865, William Sherman joined Ulysses S. Grant and the main army surrounding Richmond. On 1st April Sherman attacked the Confederate Army at Five Forks. The Confederates, led by Major General George Pickett, were overwhelmed and lost 5,200 men. On hearing the news, Robert E. Lee decided to abandon Richmond and join Joseph E. Johnston and his forces in South Carolina.

President Jefferson Davis, his family and government officials, was forced to flee from Richmond. Soon afterwards the Union Army took the city and Lincoln arrived on 4th April. Protected by ten seamen, he walked the streets and when one black man fell to his knees in front of him, Lincoln told him: "Don't kneel to me. You must kneel to God only and thank him for your freedom." Lincoln travelled to the Confederate Executive Mansion and sat for a while in the former leader's chair before heading back to Washington.

Robert E. Lee, with an army of 8,000 men, probed the Union Army at Appomattox but faced by 110,000 men he decided the cause was hopeless. He contacted Ulysses S. Grant and after agreeing terms on 9th April, surrendered his army at Appomattox Court House. Grant issued a brief statement: "The war is over; the rebels are our countrymen again and the best sign of rejoicing after the victory will be to abstain from all demonstrations in the field."

At his Cabinet meeting on 14th April, Lincoln commented: "There are many in Congress who possess feelings of hate and vindictiveness in which I do not sympathize and cannot participate." He added that enough blood had been shed and would do what he could to prevent any "vengeful actions".

That night Lincoln went to Ford's Theatre with his wife, Mary Lincoln, Clara Harris and Major Henry Rathbone to see a play called Our American Cousin. Lincoln asked Thomas Eckert, chief of the War Department telegraph office, to be his bodyguard. However, Edwin M. Stanton refused permission for Eckert to go claiming he had an important task for him to perform that night. In fact, this was not true and Eckert spent the evening at home.

John Parke, a constable in the Washington Metropolitan Police Force, was detailed to sit on the chair outside the presidential box. During the third act Parker left to get a drink. Soon afterwards, John Wilkes Booth, entered Lincoln's box and shot the president in the back of the head. Booth then jumped to the stage eleven feet below. Despite fracturing his ankle, he was able to reach his horse and gallop out of the city.

Lincoln was taken to the White House but died early the next morning. Over the next few days Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold were all arrested charged with conspiring to murder Lincoln. Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, argued that they should be tried by a military court as Lincoln had been Commander in Chief of the army. Several members of the cabinet, including Gideon Welles (Secretary of the Navy), Edward Bates (Attorney General), Orville H. Browning (Secretary of the Interior), and Henry McCulloch (Secretary of the Treasury), disapproved, preferring a civil trial. However, James Speed, the Attorney General, agreed with Stanton and the new president Andrew Johnson, ordered the formation of a nine-man military commission to try the conspirators involved in the assassination of Lincoln.

The trial began on 10th May, 1865. The military commission included leading generals such as David Hunter, Lewis Wallace, Thomas Harris and Alvin Howe. Joseph Holt was chosen as the the government's chief prosecutor. During the trial Holt attempted to persuade the military commission that Jefferson Davis and the Confederate government had been involved in conspiracy.

Joseph Holt attempted to obscure the fact that there were two plots: the first to kidnap and the second to assassinate. It was important for the prosecution not to reveal the existence of a diary taken from the body of John Wilkes Booth. The diary made it clear that the assassination plan dated from 14th April. The defence surprisingly did not call for Booth's diary to be produced in court.

On 29th June, 1865 Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold were found guilty of being involved in the conspiracy to murder Lincoln. Surratt, Powell, Atzerodt and Herold were hanged at Washington Penitentiary on 7th July, 1865. Surratt, who was expected to be reprieved, was the first woman in American history to be executed.

The decision to hold a military court received further criticism when John Surratt, who faced a civil trial in 1867, was not convicted by the jury. Michael O'Laughlin died in prison but Samuel Mudd, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold were all pardoned by President Andrew Johnson in 1869.

On this day in 1828 George Meredith, the only child of Augustus Urmston Meredith (1797–1876) and Jane Eliza Macnamara (1802–1833), was born at 73 High Street, Portsmouth on 12th February 1828. His mother died when he was five years old.

Meredith was educated at St Paul's School in Southsea and at a boarding-school in Suffolk. In August 1842 he was sent to a school in Neuwied near Koblenz. On his return to England he was articled to Richard Stephen Charnock, a London solicitor.

Meredith married a widow, Mary Ellen Nicolls (1821–1861) on 9th August 1849. Meredith had a strong interest in literature and had several articles published in Fraser's Magazine. In 1851 he published a volume of poems. His wife shared his literary interests but it was not a happy marriage. He later wrote "No sun warmed my roof-tree; the marriage was a blunder". Although his wife became pregnant more than once, only one child survived infancy, Arthur Meredith, born on 13th June 1853.

Meredith associated with a group of writers and artists. This included Henry Wallis and in 1855 he agreed to model for his famous painting, The Death of Chatterton. Soon afterwards, Meredith's wife began an affair with Wallis. She eventually left Meredith to live with Wallis.

Meredith published his first work of fiction, The Shaving of Shagpat: an Arabian Entertainment, in 1856. George Eliot described the book as "a work of genius". This was followed by Farina: a Legend of Cologne (1857). His novel, The Ordeal of Richard Feverel: a History of Father and Son (1859) was according to his biographer, Margaret Harris, "fuelled by the trauma of sexual betrayal." Meredith's next novel, Evan Harrington, was serialized in Once a Week magazine from February to October 1860.

At the time his work was considered to be similar to Charles Dickens. However, his books did not sell well and he was forced to became a publisher's reader for Chapman and Hall. It is claimed that he read about ten manuscripts a week. Meredith was the first to discover the talents of Thomas Hardy. After reading his first novel, The Poor Man and the Lady, he advised him to rewrite it as in its current state it would be perceived as "socialistic" or even "revolutionary" and that as a result would not be well-received by the critics. Meredith went on to argue that this might prove to be handicap to Hardy's future career. He suggested that Hardy should either rewrite the story or write another novel with a different plot.

Claire Tomalin, the author of Thomas Hardy: The Time Torn Man (2006) has pointed out: "George Meredith, a handsome man of forty in a frock coat, with wavy hair, moustache, and brown beard. At first Hardy did not realize he was the novelist, but he listened to his advice, which was that he would do better not to publish this book: it would certainly bring down attacks from reviewers and damage his future chances as a novelist." Hardy later reported that he appreciated Meredith's "trenchant" comments and that "he gave me no end of good advice, most of which, I am bound to say, he did not follow himself". With the help of Meredith the young novelist produced the best-selling Far From the Madding Crowd. Meredith also helped other young writers including Olive Schreiner and George Gissing, get their work published.

Meredith published Modern Love in 1862 deals with his relationship with his first wife who had died the previous year. Margaret Harris argues: "The fifty sixteen-line sonnets play out the end of a love affair in a narrative which dwells on representing states of mind and shifts of perception rather than on an objective account of what actually took place." Richard Holt Hutton, in his review of the book in The Spectator, suggested that: "Mr George Meredith is a clever man, without literary genius, taste or judgement." However, it received great praise from Algernon Charles Swinburne who claimed that Meredith is a poet "whose work, perfect or imperfect, is always as noble in design as it is often faultless in result".

Meredith met Marie Vulliamy (1840–1885) in 1863. He later wrote: "I knew when I spoke to her that hers was the heart I had long been seeking, and that my own in its urgency was carried on a pure though a strong tide". The couple married at Mickleham Parish Church on 20th September 1864. Marie gave birth to two children: William Maxse (1865) and Marie Eveleen (1871).

The journalist, Francis Burnand, was a close friend during this period. In his autobiography Records and Reminiscences (1904), he recalled: "George Meredith never merely walked, never lounged; he strode, he took giant strides. He had… crisp, curly, brownish hair, ignorant of parting; a fine brow, quick, observant eyes, greyish - if I remember rightly - beard and moustache, a trifle lighter than the hair. A splendid head; a memorable personality. Then his sense of humour, his cynicism, and his absolutely boyish enjoyment of mere fun, of any pure and simple absurdity. His laugh was something to hear; it was of short duration, but it was a roar; it set you off - nay, he himself, when much tickled, would laugh till he cried (it didn't take long to get to the crying), and then he would struggle with himself, hand to open mouth, to prevent another outburst."

Merediths purchased Flint Cottage, Box Hill, Dorking, in 1867. It was to remain their home for the rest of their lives. His next novel, The Adventures of Harry Richmond, illustrated by George Du Maurier, was serialised in The Cornhill Magazine from September 1870 to November 1871. This was followed by Beauchamp's Career, that was serialised in The Fortnightly Review from August 1874 to December 1875.

The writer Frank Harris became very close to Meredith. In his autobiography, My Life and Loves (1922), he explained how the relationship began: "I met him for the first time in Chapman's office - to me a most memorable experience. He was one of the handsomest men I have ever seen, a little above middle height, spare and nervous; a slendid head, all framed in silver hair; but perhaps because he was very deaf himself, he used to speak very loudly."

The short stories, The House on the Beach: a Realistic Tale, The Case of General Ople and Lady Camper, and The Tale of Chloe were published in the Quarterly Magazine. This was followed by his best known work, The Egoist: a Comedy in Narrative, that was serialized in the Glasgow Weekly Herald (June 1879 - Jan 1880). As Margaret Harris has pointed out: "Now acknowledged as his masterpiece, this highly structured novel both articulates Meredith's particular idea of comedy as ‘the ultimate civilizer’ and draws on the traditions of stage comedy of Molière and Congreve. While celebrating these various literary traditions, The Egoist also engages with such significant Victorian discourses as evolution and imperialism."

The poet James Thomson was a great supporter of Meredith's work. In an article on Meredith in May, 1876, he wrote: "His name and various passages in his works reveal Welsh blood, more swift and fiery and imaginative than the English.... So with his conversation. The speeches do not follow one another mechanically, adjusted like a smooth pavement for easy walking; they leap and break, resilient and resurgent, like running foam-crested sea-waves, impelled and repelled and crossed by under-currents and great tides and broad breezes; in their restless agitations you must divine the immense life abounding beneath and around and above them."

Frank Harris also thought highly of Meredith. He once told him "I look upon you as only second to the very greatest, to my heroes: Shakespeare, Goethe, and Cervantes." Harris said that Meredith turned away, perhaps to hide his emotion: "Strange, that is what I have sometimes thought of myself, but I never hoped to hear it said." Harris argued in his autobiography: "Meredith was the most interesting of companions. We agreed in almost everything but the flashes of his humour made his conversation entrancing."

Marie Meredith died on 17th September 1885, from cancer of the throat. George Meredith's health was also poor. He suffered from various gastric ailments and later developed from motor ataxia and osteoarthritis. He also had to endure increasing deafness. However, these problems did not stop him from writing and he published several novels including One of our Conquerors (1891), Lord Ormont and his Aminta (1894) and The Amazing Marriage (1895).

Meredith associated with several leading figures in the Liberal Party. This included Herbert Asquith, John Morley and Richard Haldane. Asquith later recalled: "It is true that his conversation, particularly as he grew deafer, tended to become a monologue, but it was sprinkled with gems and never bored. He was a great improvisatore and nothing could be more exhilarating than to watch him, with his splendid head and his eyes aflame, stamping up and down the room, while he extemporized at the top of his resonant voice a sonnet in perfect form on the governess's walking costume, or a dozen lines, in the blankest of Wordsworthian verse, in elucidation of Haldane's philosophy." On the left-wing of the party he was anti-imperialist and opposed the Boer War.

Meredith was also a supporter of women's suffrage and argued "that women have brains, and can be helpful to the hitherto entirely dominant muscular creature who has allowed them some degree of influence in return for servile flatteries and the graceful undulations of the snake admired yet dreaded".

The Common Cause, the journal of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, praised the work that Meredith had done in support of the campaign: "Beyond everything, what he brought to the younger generation of women was hope and self-revelation… Now woman feels that she belongs to herself, that she possesses herself, and that unless or until she does so the gift of herself is impossible. You cannot give what you have not got. Women … would force men to look at things as they are; at women's lives as they are; at the purely masculine world in which they are compelling women to live and to which the women cannot and ought not to adapt themselves."

Despite the support he gave to the NUWSS, he was opposed to the militant tactics of the Women's Social and Political Union and following a demonstration at the House of Commons he argued in a letter to The Times: "The mistake of the women has been to suppose that John Bull will move sensibly for a solitary kick". His views were dismissed by George Bernard Shaw who described Meredith as "a Cosmopolitan Republican Gentleman of the previous generation".

Frank Harris met him for the last time in the early months of 1909. Meredith told him: "People talk about me as if I were an old man. I don't feel old in the least. On the contrary, I do not believe in growing old, and I do not see any reason why we should ever die. I take as keen an interest in the movement of life as ever, I enter into the intrigues of parties with the same keen interest as of old. I have seen the illusion of it all, but it does not dull the zest with which I enter into it, and I hold more firmly than ever my faith in the constant advancement of the race. My eyes are as good as ever they were, only for small print I need to use spectacles. It is only in my legs that I feel weaker. I can no longer walk, which is a great privation to me. I used to be a keen walker; I preferred walking to riding; it sent the blood coursing to the brain; and besides, when I walked I could go through woods and footpaths which I could not have done if I had ridden. Now I can only walk about my own garden. It is a question of nerves. If I touch anything, however, slightly, I am afraid that I shall fall - that is my only loss. My walking days are over."

George Meredith died at home in Flint Cottage on 18th May, 1909.

On this day in 1880 John Llewellyn Lewis, the son of immigrants from Wales, was born in Iowa on 12th February, 1880. At fifteen he found work as a miner in Illinois. He joined the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) and eventually was elected branch secretary.

In 1911 Lewis left the mines to become an organizer for the American Federation of Labour (AFL). In 1917 he was elected vice president of the UMWA. Three years later he became president of what was then the largest trade union in America.

In 1921 Lewis, with the support of William Z. Foster, failed in his attempt to challenge Samuel Gompers for the presidency of the American Federation of Labour.

With growing unemployment, membership of the UMWA fell from 500,000 to less than 100,000 in the 1930s. In 1935 Lewis joined with the heads of seven other unions to form the Congress for Industrial Organisation (CIO). Lewis became president of this new organization and over the next few years attempted to organize workers in the new mass production industries. This strategy was successful and by 1937 the CIO had more members than the American Federation of Labour.

Lewis had been a Republican but supported Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1932 and 1936 presidential campaigns. Although Lewis favoured many aspects of the New Deal, he was opposed to Roosevelt standing again in 1940. Lewis threatened to resign as president of the Congress for Industrial Organisation if Roosevelt was elected. He carried out this threat but retained his leadership of the United Mine Workers of America.

In the 1940s Lewis led a series of strikes that resulted in increased wages for miners. This resulted a growth in union members to 500,000. Congress responded to the success of unions such as the UMWA by passing the Taft-Hartley Act (1947) that placed new restrictions on trade unions. Lewis held the post of president of the United Mine Workers of America until 1960.

John Llewellyn Lewis, who served as chairman of the UMWA's Welfare and Retirement Fund after his retirement, died in Washington on 11th June, 1969.

On this day in 1886 Horatio Seymour, the son of a banker, was born in Pompey Hill, New York, on 31st May, 1810. Trained as a lawyer, he served as military secretary to the New York governor, William M. Marcy from 1833 to 1839.

In 1841 Seymour was elected to the lower house of the New York Legislature (1842-46). Her served as Speaker (1845-47) and in 1852 was elected as governor of New York but was defeated two years later, mainly because of his refusal to support prohibition.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War Seymour initially supported Abraham Lincoln but urged a peaceful settlement of the conflict. When he criticised Lincoln's excessive use of executive power, he was accused of being sympathetic to the Southern cause.

During the campaign, Thomas Nast, produced several cartoons for Harper's Weekly attacking his campaign. One of these drawings shows Seymour joining hands with the Irish vote and the Confederate vote to prevent the Negro from reaching the ballot box. Though Seymour ran fairly close to Grant in the popular vote (lost by 300,000 votes), he was defeated decisively in the electoral vote by a count of 214 to 80.

Seymour returned to New York politics and with Samuel Tilden helped to remove the city's corrupt mayor, Robert Tweed.

Horatio Seymour died on 12th February, 1886.

On this day in 1900 Robert Boothby, the only son of Sir Robert Tuite Boothby, was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on 12th February 1900. Boothby was educated at Eton College and at Magdalen College. After leaving university he joined a firm of stockbrokers.

Boothby was also a member of the Conservative Party and eventually East Aberdeenshire selected him as their parliamentary candidate. In 1924 he was elected to the House of Commons.

In 1926 Winston Churchill, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, appointed Boothby as his parliamentary private secretary, a post he held for three years.

In 1930 Boothby began a long affair with Dorothy Macmillan, the wife of his parliamentary colleague, Harold Macmillan. It has been claimed that he was the father of Sarah Macmillan. The writer and broadcaster Ludovic Kennedy, who is Boothby's cousin, has argued that "to my certain knowledge (Boothby) fathered at least three children by the wives of other men (two by one woman, one by another)." Boothby married Diana Cavendish but the relationship was dissolved two years later.

Boothby was a frequent visitor to Germany and in 1932 met Adolf Hitler. He was later to record that "I talked with Hitler for over an hour; and it was not long before I detected the unmistakable glint of madness in his eyes." Boothby came out of the meeting convinced that Hitler posed a serious threat to Britain's security.

In October 1933 Boothby made a speech where he warned: "If those of us who believe in freedom refuse to fight for our faith under any circumstances, then assuredly we will succumb to the military forces of Fascism or Communism, and most of the things which seem to make life worth living will be swept away."

Boothby joined a small group in the Conservative Party, including Winston Churchill and Leo Amery, that called for the government to increase spending on defence. In one speech Boothby suggested that the British government was in danger of betraying those soldiers who had been killed during the First World War. "In relation to the facts of the present situation our Air Force is pitifully inadequate. If we are strong and resolute, and if we pursue a wise and constructive foreign policy, we can still save the world from war. But if we simply drift along, never taking the lead, and exposing the heart of our Empire to an attack which might pulverize it in a few hours, then everything that makes life worth living will be swept away, and then indeed we shall have finally broken faith with those who lie dead in the fields of Flanders."

In January 1938 Boothby became the first person in public life to demand the introduction of compulsory national service. He followed this with a campaign to persuade Neville Chamberlain and his Conservative government to increase the frontline strength of the Royal Air Force from 1700 to 3500. However, both these suggestions were rejected by Chamberlain.

Robert Boothby returned to office in 1940 when Winston Churchill appointed him as Parliamentary Private Secretary to the Ministry of Food. Boothby worked under Lord Woolton and was given responsibility for devising the National Milk Scheme, which provided milk for children and nursing mothers during the Second World War.

In 1941 Boothby was forced to resign after a Select Committee published a critical report of his behaviour before the war. The committee pointed out that Boothby had made a speech where he advocated the distribution of seized Czechoslovakian assets to Czech citizens living in Britain. It was claimed that this broke the rules of the House of Commons as Boothby had not disclosed that he had a financial interest in this policy.

After resigning from office Boothby joined the Royal Air Force. After completing his training as a pilot officer he became Adjutant of Number 9 Bomber Squadron at Honington with the rank of Flight Lieutenant.

In 1948 Boothby became an original member of the Council of United Europe and was a British delegate to its consultative assembly (1949-54). Boothby was knighted in 1953 and raised to the peerage in 1958. He was also Rector of the University of St Andrews (1958-61) and Chairman of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (1961-63).

Boothby was bi-sexual and although he kept his homosexual activity a secret, he did campaign for a change in the law. In his autobiography he comments on a speech he made to the Hardwicke Society: "I said that the present law regarding homosexuality was iniquitous, and that the clause in the Act which made indecency between consenting male adults in private a crime should be removed from the Statute Book."

Boothby sent a copy of his speech to the Home Secretary, David Maxwell-Fyfe. He replied: "I am not going down to history as the man who made sodomy legal." However, he did establish a committee to look into the issue that was chaired by John Wolfenden.

Lord Boothby attended sex parties with Tom Driberg in London. He also began an affair with gangster Ronnie Kray. Boothby was on holiday with Colin Coote, the editor of the Daily Telegraph, when on 12 July 1964, the Sunday Mirror published a front page lead story under the headline: "Peer and a gangster: Yard probe." The newspaper claimed police were investigating an alleged homosexual relationship between a "prominent peer and a leading thug in the London underworld", who is alleged to be involved in a West End protection racket.

The following week the newspaper said it had a picture of the peer and the gangster sitting on a sofa. Rumours soon began circulating that the peer was Boothby and the gangster was Ronnie Kray. Stories also circulated that Harold Wilson and Cecil King, the chairman of the International Publishing Corporation were conspiring in an attempt to overthrow the Conservative government led by Alec Douglas -Home. Boothby's friend, Colin Coote used his contacts in the media to discover what was going on.

As journalist John Pearson pointed out: "By doing nothing he (Boothby) would tacitly accept the Sunday Mirror's accusations. On the other hand, to sue for libel would mean facing lengthy and expensive court proceedings which could ruin him financially - apart from whatever revelations the Sunday Mirror could produce to support its story." Boothby was then approached by two leading Labour Party figures, Gerald Gardiner, QC and solicitor Arnold Goodman. They offered to represent Lord Boothby in any libel case against the newspaper. Goodman was Wilson's "Mr Fixit" and Gardiner was later that year to become the new prime-minister's Lord Chancellor.

Boothby now wrote a letter to The Times and argued that the Sunday Mirror had been referring to him and that he intended to sue this newspaper for libel. He claimed that he had only met Kray three times. However, this had been public events in 1964 (there were published photographs of these meetings and so they could not be denied). When the case came to court, the newspaper decided not to reveal the compromising photograph. Unwilling to defend their story, Lord Boothby was awarded £40,000 and the editor of the newspaper was sacked. This resulted in other newspapers not touching the story. Scotland Yard was also ordered to drop their investigation into Boothby and Ronnie Kray.

The rumours about Boothby's homosexuality continued to circulate and in 1967 he decided to marry Wanda Sanna. According to friends, the relationship was platonic.

Boothby made frequent appearances on television and radio and wrote several books including The New Economy (1943), I Fight to Live (1947), My Yesterday, Your Tomorrow (1962) and Boothby: Recollections of a Rebel (1978).

Lord Boothby died on 16th July 1986.

On this day in 1905 Federica Montseny was born in Madrid, Spain. Her parents were the co-editors of the anarchists journal, La Revista Blanca (1898-1905). In 1912 the family returned to Catalonia and farmed land just outside Barcelona. Later they established a company that specialized in publishing libertarian literature.

Montseny joined the anarchist labour union, National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT). As well as working in the family publishing business she contributed articles to anarchist journals such as Solidaridad Obrera, Tierra y Libertad and Nueva Senda. In her writings Montseny called for women's emancipation in Spain.

In 1921 Miguel Primo de Rivera banned the CNT. It now became an underground organization and in 1927 Montseny joined the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI).

The Antifascist Militias Committee was set up in Barcelona on 24th July 1936. The committee immediately sent Buenaventura Durruti and 3,000 Anarchists to Aragón in an attempt to take the Nationalist held Saragossa. At the same time Montseny established another anarchist militia, the Tierra y Libertad (Land and Liberty).

In the first few weeks of the Spanish Civil War an estimated 100,000 men joined Anarcho-Syndicalists militias. Anarchists also established the Iron Column, many of whose 3,000 members were former prisoners. In Guadalajara, Cipriano Mera, leader of the CNT construction workers in Madrid, formed the Rosal Column.

In November 1936 Francisco Largo Caballero appointed Montseny as Minister of Health. In doing so, she became the first woman in Spanish history to be a cabinet minister. Over the next few months Montseny accomplished a series of reforms that included the introduction of sex education, family planning and the legalization of abortion.

During the Spanish Civil War the National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT), the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) and the Worker's Party (POUM) played an important role in running Barcelona. This brought them into conflict with other left-wing groups in the city including the Union General de Trabajadores (UGT), the Catalan Socialist Party (PSUC) and the Communist Party (PCE).

On the 3rd May 1937, Rodriguez Salas, the Chief of Police, ordered the Civil Guard and the Assault Guard to take over the Telephone Exchange, which had been operated by the CNT since the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. Members of the CNT in the Telephone Exchange were armed and refused to give up the building. Members of the CNT, FAI and POUM became convinced that this was the start of an attack on them by the UGT, PSUC and the PCE and that night barricades were built all over the city.

Fighting broke out on the 4th May. Later that day the anarchist ministers, Federica Montseny and Juan Garcia Oliver, arrived in Barcelona and attempted to negotiate a ceasefire. When this proved to be unsuccessful, Juan Negrin, Vicente Uribe and Jesus Hernández called on Francisco Largo Caballero to use government troops to takeover the city. Largo Caballero also came under pressure from Luis Companys, the leader of the PSUC, not to take this action, fearing that this would breach Catalan autonomy.

On 6th May death squads assassinated a number of prominent anarchists in their homes. The following day over 6,000 Assault Guards arrived from Valencia and gradually took control of Barcelona. It is estimated that about 400 people were killed during what became known as the May Riots.

These events in Barcelona severely damaged the Popular Front government. Communist members of the Cabinet were highly critical of the way Francisco Largo Caballero handled the May Riots. President Manuel Azaña agreed and on 17th May he asked Juan Negrin to form a new government. Montseny, along with other anarchist ministers, Juan Garcia Oliver, Juan López and Juan Peiró now resigned from the government.

Negrin's government now attempted to bring the Anarchist Brigades under the control of the Republican Army. At first the Anarcho-Syndicalists resisted and attempted to retain hegemony over their units. This proved impossible when the government made the decision to only pay and supply militias that subjected themselves to unified command and structure.

Negrin also began appointing members of the Communist Party (PCE) to important military and civilian posts. This included Marcelino Fernandez, a communist, to head the Carabineros. Communists were also given control of propaganda, finance and foreign affairs. The socialist, Luis Araquistain, described Negrin's government as the "most cynical and despotic in Spanish history."

At the end of the Spanish Civil War Montseny fled to France. She now led the National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT) in exile until her arrest in 1942. She was imprisoned in Perigueux and Limoges during the Second World War and was not released until the liberation of France in 1944.

Federica Montseny moved to Toulouse where she published the anarchist newspaper, L'Espoir. Unlike most other exiles, she decided not to return home after the death of General Francisco Franco and the re-introduction of democracy in Spain.

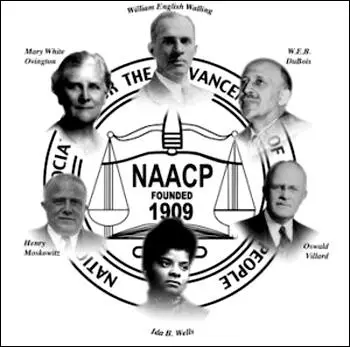

On this day in 1909 the first meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People takes place. Early members included William English Walling, Anna Strunsky, Mary Ovington, Josephine Ruffin, Mary Talbert, Lillian Wald, Florence Kelley, Mary Church Terrell, Inez Milholland, Jane Addams, George Henry White, William Du Bois, Charles Edward Russell, John Dewey, Charles Darrow, Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, William Dean Howells, Fanny Garrison Villard, Oswald Garrison Villard, Ida Wells-Barnett, Sophonisba Breckinridge, John Haynes Holmes, Mary McLeod Bethune and George Henry White.

The NAACP started its own magazine, Crisis in November, 1910. The magazine was edited by William Du Bois and contributors to the first issue included Oswald Garrison Villard and Charles Edward Russell. The magazine soon built up a large readership amongst black people and white sympathizers. By 1919 Crisis was selling 100,000 copies a month.

In 1915 the NAACP campaigned against the film Birth of a Nation (1915). The film's portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan and African Americans, resulted in the director, D.W. Griffith, being accused of racism. Despite attempts by the NAACP to have the film banned, it was highly successful at the box office.

Mary White Ovington was the first executive secretary of the NAACP. She was replaced by the writer and diplomat, James Weldon Johnson in May, 1917. His assistant was Walter Francis White, and together they managed to rapidly increase the size of the organization. In 1918 the NAACP had 165 branches and 43,994 members.

The NAACP also fought for women's suffrage. Several women, including Mary White Ovington, Jane Addams, Inez Milholland, Josephine Ruffin, Mary McLeod Bethune, Mary Talbert, Mary Church Terrell and Ida Wells-Barnett, were active in both the struggle for women's rights as well as equal civil rights.

The NAACP was also involved in legal battles against segregation and racial discrimination in housing, education, employment, voting and transportation. The NAACP appealed to the Supreme Court to rule that several laws passed by southern states were unconstitutional and won three important judgments between 1915-23 concerning voting rights and housing.

The NAACP also fought a long campaign against lynching. In 1919 it published Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States: 1889-1918. The NAACP also paid for large adverts in major newspapers presenting the facts about lynching. To show that the members of the organization would not be intimidated, it held its 1920 annual conference in Atlanta, considered at the time to be one of the most active Ku Klux Klan areas in America.

In 1929 Walter Francis White became executive secretary of the NAACP. White was an outstanding propagandist and articles that he wrote about African American civil rights appeared in a variety of journals including Collier's, Saturday Evening Post, The Nation, Harper's Magazine and the New Republic. White also wrote a regular column in the New York Herald Tribune and the Chicago Defender.

In July, 1935, Walter Francis White recruited Charles Houston, to establish a legal department for the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). The following year Houston appointed Thurgood Marshall as his assistant. Over the next few years Houston and Marshall used the courts to challenge racist laws concerning transport, housing and education.

In 1940 Thurgood Marshall became chief of the NAACP's legal department. Over the next few years Marshall won 29 of the 32 cases that he argued before the Supreme Court. This included cases concerning the exclusion of black voters from primary elections (1944), restrictive covenants in housing (1948) and unequal facilities for students in state universities (1950).

Some members of the NAACP claimed that Walter Francis White had too much power in the organization. In 1950 the NAACP board decided that Roy Wilkins should replace White as the person in charge of all internal matters. White remained the NAACP's official spokesman until his death on 21st March, 1955.

During the 1950s the main tactic of the NAACP was to use the courts to end racial discrimination in the United States. One of the objectives was the end of the system of having separate schools for black and white children in the South. The states of Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia and Kentucky all prohibited black and white children from going to the same school.

The NAACP appealed to the Supreme Court in 1952 to rule that school segregation was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court ruled that separate schools were acceptable as long as they were "separate and equal". It was not too difficult for the NAACP to provide information to show that black and white schools in the South were not equal. One study carried out in 1937 revealed that spending on white pupils in the South was $37.87 compared to $13.08 spent on black children.

After looking at information provided by the NAACP the Supreme Court announced in 1954 that separate schools were not equal and ruled that they were therefore unconstitutional. Some states accepted the ruling and began to desegregate. This was especially true of states where small black populations who had found the provision of separate schools extremely expensive.

Several states in the Deep South refused to accept the judgment of the Supreme Court. In September 1957, the governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus, used the National Guard to stop black children from attending the local high school in Little Rock. Film of the events at Little Rock was shown throughout the world. This was extremely damaging to the image of the United States.

On 24th September, 1957, President Dwight Eisenhower, went on television and told the American people: "At a time when we face grave situations abroad because of the hatred that communism bears towards a system of government based on human rights, it would be difficult to exaggerate the harm that is being done to the prestige and influence and indeed to the safety of our nation and the world. Our enemies are gloating over this incident and using it everywhere to misrepresent our whole nation. We are portrayed as a violator of those standards which the peoples of the world united to proclaim in the Charter of the United Nations."

After trying for eighteen days to persuade Orval Faubus to obey the ruling of the Supreme Court, Eisenhower decided to send federal troops to Arkansas to ensure that black children could go to Little Rock Central High School. The white population of Little Rock were furious that they were being forced to integrate their school and Faubus described the federal troops as an army of occupation. The nine black students that entered the school suffered physical violence and constant racial abuse. Although under considerable pressure to leave the school they agreed to stay. In doing so, they showed the rest of the country that African Americans were determined to obtain equality.

The NAACP was also involved in the struggle to end segregation on buses and trains. In 1952 segregation on inter-state railways was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. This was followed in 1954 by a similar judgment concerning inter-state buses. However, states in the Deep South continued their own policy of transport segregation. This usually involved whites sitting in the front and African Americans at the back. When the bus was crowded, the rule was that blacks sitting nearest to the front had to give up their seats to any whites that were standing.

African American people who disobeyed the state's transport segregation policies were arrested and fined. On 1st December, 1955, Rosa Parks, a middle-aged tailor's assistant from Montgomery, Alabama, who was tired after a hard day's work, refused to give up her seat to a white man. After her arrest, Martin Luther King, a pastor at the local Baptist Church, helped organize protests against bus segregation. It was decided that black people in Montgomery would refuse to use the buses until passengers were completely integrated. King was arrested and his house was fire-bombed. Others involved in the Montgomery Bus Boycott also suffered from harassment and intimidation, but the protest continued.

For thirteen months the 17,000 black people in Montgomery walked to work or obtained lifts from the small car-owning black population of the city. Eventually, the loss of revenue and a decision by the Supreme Court forced the Montgomery Bus Company to accept integration.

After the successful outcome of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, its leader, Martin Luther King, wrote Stride Toward Freedom (1958). The book described what happened at Montgomery and explained King's views on non-violence and direct action and was to have a considerable influence on the civil rights movement.

In Greensboro, North Carolina, a small group of black students read the book and decided to take action themselves. They started a student sit-in at the restaurant of their local Woolworth's store which had a policy of not serving black people. In the days that followed they were joined by other black students until they occupied all the seats in the restaurant. The students were often physically assaulted, but following the teachings of King they did not hit back.

King's non-violent strategy was adopted by black students all over the Deep South. This included the activities of the Freedom Riders in their campaign against segregated transport. Within six months these sit-ins had ended restaurant and lunch-counter segregation in twenty-six southern cities. Student sit-ins were also successful against segregation in public parks, swimming pools, theaters, churches, libraries, museums and beaches.

Martin Luther King travelled the country making speeches and inspiring people to become involved in the civil rights movement. As well as advocating non-violent student sit-ins, King also urged economic boycotts similar to the one that took place at Montgomery. He argued that as African Americans made up 10% of the population they had considerable economic power. By selective buying, they could reward companies that were sympathetic to the civil rights movement while punishing those who still segregated their workforce.

King also believed in the importance of the ballot. He argued that once all African Americans had the vote they would become an important political force. Although they were a minority, once the vote was organized, they could determine the result of presidential and state elections. This was illustrated by the African American support for John F. Kennedy that helped give him a narrow victory in the 1960 election.

In the Deep South considerable pressure was put on blacks not to vote by organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan. An example of this was the state of Mississippi. By 1960, 42% of the population were black but only 2% were registered to vote. Lynching was still employed as a method of terrorizing the local black population. Emmett Till, a fourteen year old schoolboy was lynched for whistling at a white woman, while others were murdered for encouraging black people to register to vote. King helped organize voting registration campaigns in states such as Mississippi but progress was slow.

During the 1960 presidential election campaign John F. Kennedy argued for a new Civil Rights Act. After the election it was discovered that over 70 per cent of the African American vote went to Kennedy. However, during the first two years of his presidency, Kennedy failed to put forward his promised legislation.

The Civil Rights bill was brought before Congress in 1963 and in a speech on television on 11th June, Kennedy pointed out that: "The Negro baby born in America today, regardless of the section of the nation in which he is born, has about one-half as much chance of completing high school as a white baby born in the same place on the same day; one third as much chance of completing college; one third as much chance of becoming a professional man; twice as much chance of becoming unemployed; about one-seventh as much chance of earning $10,000 a year; a life expectancy which is seven years shorter; and the prospects of earning only half as much."

In an attempt to persuade Congress to pass Kennedy's proposed legislation, King and other civil rights leaders organized the famous March on Washington. On 28th August, 1963, more than 200,000 people marched peacefully to the Lincoln Memorial to demand equal justice for all citizens under the law. At the end of the march King made his famous "I Have a Dream" speech.

Kennedy's Civil Rights bill was still being debated by Congress when he was assassinated in November, 1963. The new president, Lyndon Baines Johnson, who had a poor record on civil rights issues, took up the cause. Using his considerable influence in Congress, Johnson was able to get the legislation passed.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act made racial discrimination in public places, such as hotels, theaters and restaurants, illegal. It also required employers to provide equal employment opportunities. Projects involving federal funds could now be cut off if there was evidence of discriminated based on colour, race or national origin.

In 1964 the NAACP, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organised its Freedom Summer campaign. Its main objective was to try an end the political disenfranchisement of African Americans in the Deep South. Volunteers from the three organizations decided to concentrate its efforts in Mississippi. In 1962 only 6.7 per cent of African Americans in the state were registered to vote, the lowest percentage in the country. This involved the formation of the Mississippi Freedom Party (MFDP). Over 80,000 people joined the party and 68 delegates attended the Democratic Party Convention in Atlantic City and challenged the attendance of the all-white Mississippi representation.

The NAACP, CORE and SNCC also established 30 Freedom Schools in towns throughout Mississippi. Volunteers taught in the schools and the curriculum now included black history, the philosophy of the civil rights movement. During the summer of 1964 over 3,000 students attended these schools and the experiment provided a model for future educational programs such as Head Start.