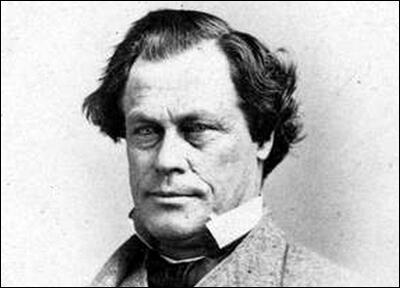

Elijah Lovejoy

Elijah Parish Lovejoy, the son of a Congregational minister, and brother of Owen Lovejoy, was born in Albion, Maine, on 9th November, 1802. After graduating from Waterville College in 1826, he moved to St. Louis, Missouri, where he established a school before attending the Princeton Theological Seminary.

In 1834 Lovejoy became the pastor of the Presbyterian Church in St. Louis. He started a religious newspaper, the St. Louis Observer, where he advocated the abolition of slavery. In 1836 Lovejoy published a full account of the lynching of an African American in St. Louis and the subsequent trial that acquitted the mob leaders. This critical report angered some local people and in July, 1836, his press was destroyed by a white mob.

Unable to publish his newspaper in St. Louis, Lovejoy moved to Alton, Illinois where he became an active member of the local Anti-Slavery Society. He also began editing the Alton Observer and continued to advocate the end of slavery.

Three times Lovejoy's printing press was seized by white mobs thrown into the Mississippi River. Lovejoy wrote in his paper: "We distinctly avow it to be our settled purpose, never, while life lasts, to yield to this new system of attempting to destroy, by means of mob violence, the right of conscience, the freedom of opinion, and of the press."

On 7th November, 1837, Lovejoy received another press from the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society. When local slave-owners heard about the arrival of the new machine, they decided to destroy it. A group of his friends attempted to protect it, but during the attack, Lovejoy was shot dead.

Elijah Parish Lovejoy was America's first martyr to freedom of the press. In 1952 the Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award was established and it is given to a member of the newspaper profession who continues the Lovejoy heritage of fearlessness and freedom.

Slavery in the United States (£1.29)

Primary Sources

(1) William Wells Brown, Narrative of William W. Brown, A Fugitive Slave (1847)

I was soon after taken from Mr. Colburn's, and hired to Elijah P. Lovejoy, who was at that time publisher and editor of the St. Louis Times. My work, while with him, was mainly in the printing office, waiting on the hands, working the press, etc. Mr. Lovejoy was a very good man, and decidedly the best master that I had ever had. I am chiefly indebted to him, and to my employment in the printing office, for what little learning I obtained while in slavery.

(2) Alton Observer ( November, 1837)

Night had come to the town of Alton, Illinois and a crowd began to gather in the darkness.

Some of the men stooped to gather stones. Others fingered the triggers of the guns they carried as they made their way to a warehouse on the banks of the Mississippi River.

As they approached, they eyed the windows of the three-story building, searching for some sign of movement from inside. Suddenly, William S. Gilman, one of the owners of the building, appeared in an upper window.

"What do you want here?" he asked the crowd.

"The press!" came the shouted reply.

Inside the warehouse was Elijah Parish Lovejoy, a Presbyterian minister and editor of the Alton Observer. He and 20 of his supporters were standing guard over a newly arrived printing press from the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society. This was the fourth press that Lovejoy had received for his paper. Three others already had been destroyed by people who opposed the antislavery views he expressed in the Observer. But Lovejoy would not give up.

This time, in an attempt to hide the arrival of the new press, secret arrangements were made. A steamboat delivered the press at 3 o'clock in the morning on November 7, 1837, and some of Lovejoy's friends were there to meet it. Moving quickly, they carried the press to the third floor of Gilman's warehouse, but not before they were spotted by members of the mob.

Word of the arrival of the press spread throughout the town all that day. As nightfall approached, mob leaders were joined by men from the taverns, and now the crowd stood below, demanding this fourth press.

Gilman called out: "We have no ill feelings toward, any of you and should much regret to do any injury; but we are authorized by the Mayor to defend our property and shall do so with our lives." The mob began to throw stones, breaking out all the windows in the warehouse.

Shots were fired by members of the mob, and rifle balls whizzed through the windows of the warehouse, narrowly missing the defenders inside. Lovejoy and his men, returned the fire. Several people in the crowd were hit, and one was killed.

"Burn them out!", someone shouted. Leaders of the mob called for a ladder, which was put up on the side of the building. A boy with a torch was sent up to set fire to the wooden roof. Lovejoy and one of his supporters, Royal Weller, volunteered to stop the boy. The two men crept out-side, hiding in the shadows of the building. Surprising the mob, they rushed to the ladder, pushed it over and quickly retreated inside.

Once again a ladder was put in place. As Lovejoy and Weller made another brave attempt to overturn the ladder, they were spotted. Lovejoy was shot five times, and Weller was also wounded. Lovejoy staggered inside the warehouse, making his way to the second floor before he finally fell.

"My God. I am shot," he cried. He died almost immediately.

By this time the warehouse roof had begun to burn. The men remaining inside knew they had no choice but to surrender the press.

The mob rushed into the vacant building. The press Lovejoy died defending was carried to a window and thrown out onto the river bank. It was broken into pieces that were scattered in the Mississippi River.

Fearing more violence, Lovejoy's friends, did not remove his body from the building until the next morning.

Members of the crowd from the night before, feeling no shame at what they had done, laughed and jeered as the funeral wagon moved slowly down the street toward Lovejoy's home. Lovejoy was buried on November 9, 1837, his 35th birthday.