On this day on 8th January

On this day in 1867 suffragist Emily Balch was born in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. Her father had been a strong supporter of Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War. According to Harriet Hyman Alonso: "Her father had a Union connection with the Civil War... As a result, racial justice was also a topic for discussion in the environment in which she grew up."

After graduating from Bryn Mawr College in 1889, Balch continued her studies in Paris and Berlin. On the arrival back in the United States she attended the University of Chicago before beginning her teaching career at Wellesley College. During this period he published Outline of Economics (1899) and A Study of Conditions of City Life (1903). Gradually, her political views became more left-wing and in 1906 she declared herself to bge a socialist.

Balch was a regular visitor at Hull House and developed a close friendship with its members including Jane Addams, Ellen Starr, Julia Lathrop, Florence Kelley, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Alice Hamilton, Mary McDowell, Mary Kenney, Alzina Stevens and Sophonisba Breckinridge. Balch studied the life of immigrants in Chicago. Her research resulted in the book, Our Slavic Fellow Citizens (1910).

On the outbreak of the First World War, Balch and a group of women pacifists in the United States, began talking about the need to form an organization to help bring it to an end. On the 10th January, 1915, over 3,000 women attended a meeting in the ballroom of the New Willard Hotel in Washington and formed the Woman's Peace Party. Addams was elected chairman and other women involved in the organization included Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley, Alice Hamilton, Anna Howard Shaw, Belle La Follette, Fanny Garrison Villard, Jeanette Rankin, Lillian Wald, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Mary Heaton Vorse, Freda Kirchwey, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Crystal Eastman, Carrie Chapman Catt, Emily Bach, and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

In April 1915, Arletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited members of the Woman's Peace Party to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Jane Addams was asked to chair the meeting and Balch, Alice Hamilton, Mary Heaton Vorse, Julia Lathrop, Leonora O'Reilly, Sophonisba Breckinridge and Grace Abbott went as delegates from the United States. Others who went to the Hague included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, (England); Chrystal Macmillan (Scotland) and Rosika Schwimmer (Hungary). Afterwards, Balch, Addams, Jacobs, Macmillan and Schwimmer went to to London, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Rome and Paris to speak with members of the various governments in Europe. During this time they met Edward Grey (13th May), Herbert Asquith (14th May), Gottlieb von Jagow (21st May), Theobold von Bethmann-Hollweg (22nd May), Karl von Sturgkh (26th May), Théophile Delcassé (12th June) and Rene Viviani (14th June).

Emily Balch was also a member of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). As a result of her anti-war activities, Balch was dismissed as professor of political economy at Wellesley College. She now concentrated on her peace work and became secretary of the WILPF (1918-22 and 1934-35). However, the emergence of Adolf Hitler changed her views on pacifism. She wrote: "It is not enough to sweep before your own door, nor to cultivate your own garden, nor to put out the fire when your own house is burning and disinterest yourself, as the diplmats say, when the frame house next door is in flames and the children calling from its nursery windows to be taken out."

Balch won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1946. In her later life Balch wrote several important books including Refugees as Assets (1939), One Europe (1947) and Toward Human Unity, or Beyond Nationalism (1952). A few weeks before she died she wrote in her diary: "I am bringing my days to a close in a world still hag-ridden by the thought of war, and it is not given to us in this new atomic world to know how things will turn out. But when I reflect on the enormous changes that I have seen myself and the amazing resiliency and resourcefulness of mankind, how can I fail to be of good courage." Emily Balch died aged 94 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on 9th January, 1961.

On this day in 1880 Octavia Wilberforce, the daughter of Reginald and Anna Wilberforce, was born in East Lavington House, Petworth on 8th January 1888. Octavia was the granddaughter of Samuel Wilberforce (1805-1873), Bishop of Winchester, the son of William Wilberforce (1759-1833), the leader of the campaign against the slave trade.

According to her biographer, Pat Jalland: "Although Octavia was the least welcome of her parents' children, she recalled her childhood as happy, because she was allowed to run wild. Her education consisted primarily of sporadic lessons in music, history, and literature, from occasional tutors, with only one year of formal education at the age of sixteen."

In July 1909, Octavia met Elizabeth Robins, the campaigner for women's rights. Octavia later recalled: "It was a turning point in my life… I had always read omnivorously and longed to write myself, and to meet so distinguished an author in the flesh was a terrific adventure. It was a small family luncheon at Phyllis Buxton's house. Elizabeth Robins was dressed in a blue suit, the colour of speedwell, which matched her beautiful deep-set eyes. I was introduced as Phyllis's friend who lives near Henfield... Elizabeth Robins.... with a charming grace and in an unforgettable voice asked me if I would come to tea one day and she would show me her modest little garden."

In 1910 Octavia was worried about the health of her housemaid. It was suggested that she took her housemaid to see Louisa Martindale, one of the new doctors at Brighton County Hospital. Octavia became friends with Louisa and after a while decided that she would also like to be a doctor. However, her parents were totally opposed to the idea and refused to fund her studies.

Reginald Wilberforce had arranged for Octavia to marry Charles Buxton, the eldest son of Lord Buxton, a wealthy businessman and prominent politician. Octavia refused to marry Charles and insisted that she wanted a career in medicine. Her father was so angry at her decision that he cut Octavia out of his will.

When Elizabeth Robins heard of Octavia's problems, she offered to help fund her studies. Octavia went to live with Robins her 15th century farmhouse at Backsettown, near Henfield. When the British government introduced the Cat and Mouse Act in 1913, Robins used her house as a retreat for suffragettes recovering from hunger strike. It was also rumoured that the house was used as a hiding place for suffragettes on the run from the police.

In 1913 Octavia Wilberforce was able to start her course at the London School of Medicine for Women. She later recalled she was met by Elizabeth Garrett Anderson "who was white-haired and gracious, and who said something tactful about William Wilberforce's great work for the slaves." She added: "Most of the girls were younger than I was and of varied types. Some of them by doing Medicine were following in a parent's footstep; some had a definite urge, like myself, to be of the use to the community. These were subdivided into those who wished to be medical missionaries and those who had worked in the Suffrage movement."

As her biographer, Pat Jalland, has pointed out: "Only 3 per cent of qualified doctors were female in 1913 and prejudice persisted against women in private practice." During the First World War the student Octavia Wilberforce, gained valuable experience treating British casualties at St. Mary's Hospital in Paddington.

Octavia Wilberforce qualified as a doctor in 1920. After working as a clinical clerk to Dr Wilfred Harris, an outstanding neurologist, and after qualifying became his house physician in 1921 she established her own general medical practice at 24 Montpelier Crescent in 1923. Octavia joined Elizabeth Robins and Louisa Martindale in their campaign for a new fifty-bed, women's hospital in Brighton. After the New Sussex Hospital for Women in Brighton opened, Octavia became one of the three visiting doctors. Later she was appointed as the hospital's head physician.

In 1927 Octavia Wilberforce helped Elizabeth Robins and Marjorie Hubert set up a convalescent home at Backsettown, for overworked professional women. Wilberforce used the convalescent home as a means of exploring the best way of helping people to become fit and healthy. Patients were instructed not to talk about illness. Octavia believed diet was very important and patients were fed on locally produced fresh food. Whenever possible, patients were encouraged to eat their meals in the garden.

During the Second World War Octavia's long-tern companion, Elizabeth Robins went back to the United States. Octavia remained in Brighton and in 1941 treated Virginia Woolf. Her husband, Leonard Woolf, later recalled: "She (Octavia Wilberforce) had, to all intents and purposes become Virginia's doctor, and so the moment I became uneasy about Virginia's psychological health in the beginning of 1941 I told Octavia and consulted her professionally. The desperate difficulty which always presented itself when Virginia began to be threatened with a breakdown - a difficulty which occurs, I think, again and again in mental illness - was to decided how far it was safe to go in urging her to take steps - drastic steps - to ward off the attack."

At the age of eighty-eight, she returned to live with Octavia at her house in Montpelier Crescent in Brighton. One of her regular visitors was Leonard Woolf. He recalled in his autobiography, The Journey Not the Arrival Matters (1969): "Elizabeth was, I think, devoted to Octavia, but she was also devoted to Elizabeth Robins; when we first knew her, she was already a elderly woman and a dedicated egoist, but she was still a fascinating as well as an exasperating egoist."

Octavia Wilberforce retired from the New Sussex Hospital for Women in 1954, but she continued to work at Backsettown until her death on 3rd January 1963.

On this day in 1885 Abraham Muste was born in Zierkzee, Holland. His family moved to the United States in 1891. His father was supporter of the Republican Party and as a young man he shared his conservative views. In 1909 he was ordained a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church.

Muste became increasingly radical and in the 1912 presidential campaign supported Eugene Debs, the Socialist Party candidate. On the outbreak of the First World War Muste left the Dutch Reformed Church and became a pacifist. In 1919 he played an active role in supporting workers during the Lawrence Textile Strike and later moved to Boston where he found work with the American Civil Liberties Union. In the early 1920s Muste worked as director of the Brookwood Labor College in Katonah, Westchester County. He also joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR).

Muste was disturbed by the events that were taking place in the Soviet Union. He no longer felt he could support the policies of Joseph Stalin. Muste now decided to join with other like-minded people to form the American Workers Party (AWP). Established in December, 1933, Muste became the leader of the party and other members included Sidney Hook, Louis Budenz, James Rorty, V.F. Calverton, George Schuyler, James Burnham, J. B. S. Hardman and Gerry Allard.

Hook later argued in his autobiography, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987): "The American Workers Party (AWP) was organized as an authentic American party rooted in the American revolutionary tradition, prepared to meet the problems created by the breakdown of the capitalist economy, with a plan for a cooperative commonwealth expressed in a native idiom intelligible to blue collar and white collar workers, miners, sharecroppers, and farmers without the nationalist and chauvinist overtones that had accompanied local movements of protest in the past. It was a movement of intellectuals, most of whom had acquired an experience in the labor movement and an allegiance to the cause of labor long before the advent of the Depression."

Soon after its formation of the AWP, leaders of the Communist League of America (CLA), a group that supported the theories of Leon Trotsky, suggested a merger. Sidney Hook, James Burnham and J. B. S. Hardman were on the negotiating committee for the AWP, Max Shachtman, Martin Abern and Arne Swabeck, for the CLA. Hook later recalled: "At our very first meeting, it became clear to us that the Trotskyists could not conceive a situation in which the workers' democratic councils could overrule the Party or indeed one in which there would be plural working class parties. The meeting dissolved in intense disagreement." However, despite this poor beginning, the two groups merged in December 1934.

In 1940 Abraham Muste was appointed executive secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). In this position Muste led the campaign against United States involvement in the Second World War. In 1942 Muste encouraged James Farmer and Bayard Rustin to establish the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). Early members included George Houser and Anna Murray. Members were mainly pacifists who had been deeply influenced by Henry David Thoreau and the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign that he used successfully against British rule in India. The students became convinced that the same methods could be employed by blacks to obtain civil rights in America.

After the war Muste joined with David Dillinger and Dorothy Day to establish the Direct Action magazine in 1945. Dellinger once again upset the political establishment when he criticised the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In early 1947, CORE announced plans to send eight white and eight black men into the Deep South to test the Supreme Court ruling that declared segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional. organized by George Houser and Bayard Rustin, the Journey of Reconciliation was to be a two week pilgrimage through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky.

The Journey of Reconciliation began on 9th April, 1947. The team included George Houser, Bayard Rustin, James Peck, Igal Roodenko, Joseph Felmet, Nathan Wright, Conrad Lynn, Wallace Nelson, Andrew Johnson, Eugene Stanley, Dennis Banks, William Worthy, Louis Adams, Worth Randle and Homer Jack.

Members of the Journey of Reconciliation team were arrested several times. In North Carolina, two of the African Americans, Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson, were found guilty of violating the state's Jim Crow bus statute and were sentenced to thirty days on a chain gang. However, Judge Henry Whitfield made it clear he found that behaviour of the white men even more objectionable. He told Igal Roodenko and Joseph Felmet: "It's about time you Jews from New York learned that you can't come down her bringing your niggers with you to upset the customs of the South. Just to teach you a lesson, I gave your black boys thirty days, and I give you ninety."

The Journey of Reconciliation achieved a great deal of publicity and was the start of a long campaign of direct action by the Congress of Racial Equality. In February 1948 the Council Against Intolerance in America gave George Houser and Bayard Rustin the Thomas Jefferson Award for the Advancement of Democracy for their attempts to bring an end to segregation in interstate travel.

The Congress of Racial Equality also organised Freedom Rides in the Deep South. In Birmingham, Alabama, one of the buses was fire-bombed and passengers were beaten by a white mob. Norman Thomas described these young people as "secular saints" I. F. Stone has argued: They and a few white sympathizers as youthful and devoted as themselves have begun a social revolution in the South with their sit-ins and their Freedom Rides. Never has a tinier minority done more for the liberation of a whole people than these few youngsters of C.O.R.E. (Congress for Racial Equality) and S.N.C.C. (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee)."

By 1961 Congress of Racial Equality had 53 chapters throughout the United States. Two years later, the organization helped organize the famous March on Washington. On 28th August, 1963, more than 200,000 people marched peacefully to the Lincoln Memorial to demand equal justice for all citizens under the law. At the end of the march Martin Luther King made his famous "I Have a Dream" speech.

Muste was also very active in the War Resisters League and helped influence civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King and Whitney Young, to oppose the Vietnam War. Abraham Muste died on 11th February, 1967.

On this day in 1891 Storm Jameson was born in Whitby. Her father and grandfather were successful shipbuilders. She studied at University of Leeds and was elected Secretary of the Women's Representative Council.

Jameson became a socialist at university and was a strong advocate of women having the vote. She also raised funds for the families of union members who took part in the strike that took place in the tailoring industry in Leeds in 1911.

After obtaining a first-class degree in English at the University of Leeds she moved to London in September 1912 and found employment at the Working Women's College in Earls Court. She wrote later that: "I believe that there exists in the intellect of the working class a vigour and freshness that may well bring forth a new Renaissance. For generations crushed under the industrial slavery, I believe that it will move when it does move, with a mighty bound."

Storm Jameson became active in politics and joined the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). In 1913 she took part in the Women's Pilgrimage to show the House of Commons how many women wanted the vote. Members of the NUWSS set off in the middle of June, and during the next six weeks held a series of meetings all over Britain. An estimated 50,000 women reached Hyde Park in London on 26th July. According to her autobiography, she bit a policeman, during the demonstration.

On 15th January 1913, Jameson married Charles Douglas Clarke, a fellow student at University of Leeds. They lived in a small flat in Shepherd's Bush. According to the author of Margaret Storm Jameson: A Life (2009): "They were very poor, she lunched regularly on plums, and they squabbled bitterly. She tried to commit suicide with an overdose of phenacetin, and he was deeply unsympathetic. She fell ill at the end of the year and went home to her parents in Whitby, while he moved in with his Quaker parents in North London."

Jameson had two articles published in New Age. The first was an attack on the work of George Bernard Shaw. She criticised his plays for their "poor characterisation" and for the "half-baked ideas" that had come from his membership of the Fabian Society. The second article dealt with the unfairness of marriage laws. Jameson also wrote an article for The Egoist that explored the political ideas of Emma Goldman.

Soon after the outbreak of the First World War, Storm Jameson's father joined the Royal Navy and became captain of the Saxon Prince. In the spring of 1916 the ship was sunk off the Irish coast and Jameson was taken prisoner and sent to a military camp at Hamburg.

Her brother, Harold Jameson, although only seventeen, joined the Royal Flying Corps. By 1916 he was a 2nd Lieutenant and had been given the DCM: "for conspicuous coolness and gallantry on several occasions in connection with wireless work under fire." Later that year he won the Military Cross for attacking a German kite balloon under heavy fire. He was killed in January 1917 after being shot down while over No Man's Land.

As Martin Ceadel, the author of Pacifism in Britain 1914-1945 (1980) has pointed out: "Her sense of outrage at the Great War in which so many of her contemporaries, including her brother, had been killed suddenly erupted into overt pacifism... Brooding upon the depressing consequences of the war, she felt an acute sense of guilt at having supported it, and turned her book into an outspoken anti-war polemic.... By the end she had gone so far as to declare herself a pacifist." After the war she joined the Women's International League. Other members included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Chrystal Macmillan, Sylvia Pankhurst, Charlotte Despard, Helen Crawfurd, Mary Barbour, Agnes Dollan, Ethel Snowden, Ellen Wilkinson, Selina Cooper, Margery Corbett-Ashby, Helena Swanwick and Olive Schreiner.

Her first novel, The Pot Boils, was published in 1919. Her marriage to Charles Douglas Clarke came to an end and in January 1924 she met Guy Chapman. He later commented: "She was wearing a heavy coat over a faded pink knitted dress, and a hat which did not suit her, and she smiled at me. She was rather lovely, with long cool grubby fingers, and she held herself badly: she made me think of a well-bred foal, unbroken and enchantingly awkward. Something she said at that first meeting, I forget what, made me laugh with pure pleasure."

They soon began a relationship. The couple married on 1st February 1926. Later she wrote: "We went to places, obscure ruined monasteries, small provincial art galleries, the house in which a dead philosopher spent his life, salt marshes, trout streams, some turn in a rough nameless road which offered a view of a smiling valley and a line of hills, because, although he had not seen them, he knew they were there. He made all other company a little dull."

Storm Jameson continued to write novels, including a trilogy about a family of Yorkshire shipbuilders: The Lovely Ship (1927), The Voyage Home (1930) and a Richer Dust (1931). Other books include Women Against Men (1933), Company Parade (1934), Love in Winter (1935), and None Turn Back (1936). Jameson also published poems, essays, biographies and several volumes of autobiography including No Time Like the Present (1933).

In September 1932 Storm Jameson became close friends with Vera Brittain. The two women had both lost brothers during the First World War and as a result became committed pacifists. Jameson reviewed Testament of Youth in the Sunday Times and said that as a representation of war from a woman's perspective "makes it unforgettable".

Storm Jameson became involved with the British section of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers. At a meeting in January 1934 it was decided to publish a new Marxist journal. The Left Review first appeared in October 1934. Contributors included Storm Jameson, Edgell Rickword, Tom Wintringham, Ralph Fox, John Strachey, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Montagu Slater, A.L. Lloyd, Hugh MacDiarmid, Amabel Williams-Ellis, A. L. Morton, Nancy Cunard, F. D. Kingender, Valentine Ackland, W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender, Edward Upward, Cecil Day-Lewis, Randall Swingler, Jack Lindsay, Margaret Storm Jameson, Naomi Mitchison, Winifred Holtby, Henry Hamilton Fyfe, Eric Gill, Herbert Read and George Barker.

On 7 July, 1934, the British Union of Fascists held a large rally at Olympia. About 500 anti-fascists including Storm Jameson, Vera Brittain, Richard Sheppard and Aldous Huxley, managed to get inside the hall. When they began heckling Oswald Mosley they were attacked by 1,000 black-shirted stewards. Several of the protesters were badly beaten by the fascists. Jameson argued in The Daily Telegraph: "A young woman carried past me by five Blackshirts, her clothes half torn off and her mouth and nose closed by the large hand of one; her head was forced back by the pressure and she must have been in considerable pain. I mention her especially since I have seen a reference to the delicacy with which women interrupters were left to women Blackshirts. This is merely untrue... Why train decent young men to indulge in such peculiarly nasty brutality? There was a public outcry about this violence and Lord Rothermere and his Daily Mail withdrew its support of the BUF. Over the next few months membership went into decline.

Jameson also became friendly with Richard Sheppard, a canon of St. Paul's Cathedral. He had been an army chaplain during the First World War. A committed pacifist, he was concerned by the failure of the major nations to agree to international disarmament and on 16th October 1934, he had a letter published in the Manchester Guardian inviting men to send him a postcard giving their undertaking to "renounce war and never again to support another." Within two days 2,500 men responded and over the next few weeks around 30,000 pledged their support for Sheppard's campaign.

In July 1935 Sheppard chaired a meeting of 7,000 members of his new organization at the Albert Hall in London. Eventually named the Peace Pledge Union (PPU), it achieved 100,000 members over the next few months. The organization now included other prominent religious, political and literary figures including Storm Jameson, Arthur Ponsonby, George Lansbury, Vera Brittain, Wilfred Wellock, Max Plowman, Maude Royden, Frank P. Crozier, Alfred Salter, Ada Salter, Siegfried Sassoon, Donald Soper, Aldous Huxley, Laurence Housman and Bertrand Russell.

Jameson was also concerned with the emergence of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany. In an article for Time and Tide on 6th June, 1936 she called for the Labour Party to work with the Communist Party of Great Britain to create a Popular Front movement. "The reanimation of the Labour Party - by (1) a change in its constitution. The statement that the Labour Party is ruled by the Trade Unions is delusive. As constituted, it is ruled by a narrow oligarchy of Trade Union leaders, as much out of touch with their rank and file as is the executive of the Labour Party with the Party rank and file. (2) An alliance, on the basis of an exactly defined programme, with the progressive Liberals, I.L.P. and Communist Party, as distinct from a shabby vote-catching agreement between leaders - is a preliminary step towards the only form of Popular Front worth voting for. Apart from a People's Front, what indeed is there to hope for in the political future? And without it, what hope of averting the eventual triumph of reaction by the default of the Labour Party?"

Storm Jameson remained a member of Peace Pledge Union until Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of France in May 1940. She wrote: "I had joined Dick Shepherd when he started it, in October 1934. Then, I was absolutely certain that war is viler than anything else imaginable... I don't think that now."

Jameson published a second volume of autobiography, Journey from the North in 1969. For many years Jameson was president of the International Association of Poets, Playwrights, Editors, Essayists and Novelists (PEN).

After her husband's death on 30th June 1972, Storm Jameson edited A Kind of Survivor (1975), a selection of Chapman's autobiographical writings. Storm Jameson died on 30th September 1986.

On this day in 1900 John Travers Cornwell, the son of Eli and Alice Cornwall, was born in Leyton, Essex, on 8th January, 1900. When he was a child the family moved to Alverstone Road, East Ham.

Cornwall left school at the age of 14 and found employment as a delivery boy. On the outbreak of the First World War his father joined the British Army. His older brother, Arthur Cornwall, also joined the army and served on the Western Front.

In October 1915 John Cornwall joined the Royal Navy as a boy sailor. After receiving his basic training at Keynham Naval Barracks at Plymouth he joined HMS Chester at Rosyth, Scotland.

After the outbreak of the First World War, attempts were made to draw the smaller German Navy into the North Sea for a major battle. Admiral Hugo von Pohl, the commander of the German High Seas Fleet, resisted these temptations, but in February 1916, he was replaced by the much more aggressive, Admiral Reinhardt von Scheer.

In May 1916 Scheer decided that he would take on the might of the British Navy. As a bait, Scheer ordered Admiral Franz von Hipper and 40 ships to begin a sweep along the Danish coast. When he heard the news, Admiral John Jellicoe, who was at Rosyth, gave instructions for the Grand Fleet to put to sea.

With the absence of reconnaissance aircraft, both Jellicoe and Scheer sent out scouting cruisers to locate the position of the enemy. The two sets of scouting cruisers made contact and after a brief gunfire exchange, returned to guide their fleets to battle.

Meanwhile, Admiral David Beatty, and 52 ships, including HMS Chester, had left Scarpa Flow in the Orkneys and were on the way to join Admiral Jellicoe and the Grand Fleet. At 15.45, Beatty came into contact with Admiral Franz von Hipper and his 40 ships. The two fleets opened fire at a range of 15 kilometres. The hazy visibility created problems for both sides but the position of the sun gave a significant advantage to the German captains.

During this exchange of fire at the Battle of Jutland Cornwall was severely wounded. He remained at his post until HMS Chester retired from the action with only one main gun still working. According to one report: "Cornwell was found to be sole survivor at his gun, shards of steel penetrating his chest, looking at the gun sights and still waiting for orders".

Cornwall was taken to Grimsby General Hospital and his family were informed that he was seriously wounded. John Cornwall died of his wounds on 2nd June 1916 and was buried at Manor Park Cemetery in London.

In September 1916 Admiral David Beatty recommended that John Travers Cornwell for a posthumous Victoria Cross and George V endorsed it. The recommendation for citation included the following: "John Travers Cornwell, who was mortally wounded early in the action, but nevertheless remained standing alone at a most exposed post, quietly awaiting orders till the end of the action, with the gun's crew dead and wounded around him. He was under 16½ years old. I regret that he has since died, but I recommend his case for special recognition in justice to his memory and as an acknowledgement of the high example set by him."

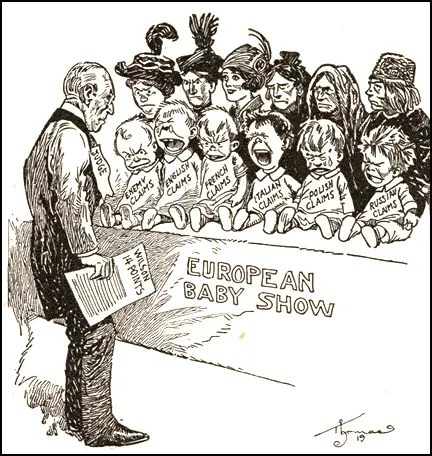

On this day in 1918 President Woodrow Wilson presented his Peace Programme to Congress.Compiled by a group of US foreign policy experts, the programme included fourteen different points. The first five points dealt with general principles: Point 1 renounced secret treaties; Point 2 dealt with freedom of the seas; Point 3 called for the removal of worldwide trade barriers; Point 4 advocated arms reductions and Point 5 suggested the international arbitration of all colonial disputes.

Points 6 to 13 were concerned with specific territorial problems, including claims made by Russia, France and Italy. This part of Wilson's programme also raised issues such as the control of the Dardanelles and the claims for independence by the people living in areas controlled by the Central Powers. All the major countries involved in the First World War objected to certain points in Wilson's Peace Programme. However, when peace negotiations began in October, 1918, Wilson insisted that his Fourteen Points should serve as a basis for the signing of the Armistice.

On this day in 1930 MI5 discover that journalist William Norman Ewer is a Soviet spy. William Norman Ewer was born on 22nd October, 1885. He became a journalist and in 1912 he joined the Daily Herald. Ewer was eventually appointed as the chief foreign correspondent. Other writers and cartoonists who contributed during this period included Henry Brailsford, George Lansbury, William Mellor, Evelyn Sharp, Norman Angell, George Douglas Cole, Will Dyson, John Scurr, Gerald Gould, Morgan Phillips Price, Hannen Swaffer, Vernon Bartlett, Havelock Ellis, Evelyn Sharp, Henry Nevinson, G. K. Chesterton and Hillaire Belloc.

Ewer was sent to cover the Russian Revolution. His reports included an interview with Leon Trotsky. The Daily Herald held a meeting on 31st March, 1918, where it welcomed the revolution. According to Stanley Harrison, the author of Poor Men's Guardians (1974): "It was the first of a series of huge meetings in the Albert Hall to welcome the Revolution and demand in general terms that all governments follow the Russian example in restoring freedom. twelve thousand people filled every seat and five thousand were turned away."

Ewer later wrote that by the end of the First World War the Daily Herald was "almost a national institution, a political force... its circulation was now nearer a quarter of a million." During this period Ewer joined the Communist Party of Great Britain. Christopher Andrew argues in The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) that Nikolai Klishko had started a spy-ring headed by Ewer in London.

According to Huw Richards, the author of The Bloody Circus: The Daily Herald and the Left (1997) Ramsay MacDonald wrote to the editor, Hamilton Fyfe, showing concern about Ewer's "communist sympathies". On 17th September 1925, Clifford Allen, who was on the board of directors, sent a memo arguing: "He (Ewer) should be removed at once." Fyfe refused to sack Ewer claiming that "he was the best journalist on the paper, among the best in London and kept his views out of the paper."

Hamilton Fyfe was unpopular with some members of the trade union movement. Ernest Bevin wrote: "The editor has not the real co-operation and confidence of the staff and this is not due to any lack on the part of staff to co-operate, but purely a temperamental weakness of the Editor, it is made worse by the fact that his judgment is unstable and erratic, that he has not the knowledge of the different phases of the movement that several members of the staff possess and is too susceptible to personal influence." Fyfe was unwilling to accept attempts by the TUC to control the content of the newspaper and he left on 31st August 1926 with a £750 payoff. Frederic Salusbury was appointed editor-in-chief and William Mellor became the new editor.

Christopher Andrew argues that Ewer was working with John Henry Hayes, the MP for Liverpool Edge Hill (1923-1931). They managed to recruit three members of Special Branch, Inspector Hubertus van Ginhoven, Sergeant Charles Jane and Albert Allen. All three men were arrested and Allen admitted that: "Any move that Scotland Yard was about to make against the Communist Party or any of its personnel was nearly always known well in advance to Ewer who actually warned the persons concerned of proposed activities of the Police."

The three men were dismissed from Special Branch but it was decided not to prosecute them. Guy Liddell, a senior MI5 officer, wrote in his diary that the trial would bring back memories of the Zinoviev Letter. As the arrests took place before the 1929 General Election Liddell argued "the general belief is that it was thought to be bad politics that have a show-down... it was felt generally that another Zinoviev letter incident should be avoided."

In 1930 the TUC sold a 51 per cent share of the newspaper to Odhams Press. William Mellor was elevated to the Odhams board and given a management position and Will Stevenson, a Welsh ex-miner, became the new editor. Ewer claimed that Stevenson was "a very nice mannered person, methodical, but not an innovator." Attempts were made to make it a more mainstream publication. This was a great success and by 1933 the Daily Herald became the world's best-selling daily newspaper, with certified net sales of 2 million.

Ewer became disillusioned with the Soviet Union and became an anti-communist member of the Labour Party after the Second World War. The author of The Bloody Circus: The Daily Herald and the Left (1997): "W. N. Ewer's half-century of service, follow its political development with striking precision. Once a fervent communist, he moved through disillusionment to rigidly orthodox labourism." A fellow journalist, Geoffrey Goodman remembers: "He was in no way a figure of fun. His views were pretty rigid by then, but you had to remember that this was a chap that had interviewed Trotsky on the steps of the Smolny Institute. You had to regard that with respect."

William Norman Ewer, who retired from the Daily Herald in 1964, died on 25th January 1977.

On this day in 1931 Winston Churchill explained to his son why women should never have been given the vote. Churchill had been a long time opponent of democracy. At Harrow School he studied the arguments against democracy put forward by Plato and Aristotle. As Aristotle pointed out: "When quarrels and complaints arise, it is when people who are equal have not got equal shares." One solution to this is to introduce democracy but Aristotle warned about the dangers of this system: "Democracy is when the indigent (poor), and not the men of property, are the rulers." This of course is unpopular with the ruling class. Aristotle believed the best system is when you have magnanimous rulers. "The magnanimous man, since he deserves most, must be good, in the highest degree; for the better man always deserves more, and the best man most. Therefore the truly magnanimous man must be good. And greatness in every virtue would seem to be characteristic of the magnanimous man." Aristotle then goes on to suggest that monarchy is the best form of government, and aristocracy the next best. Monarchs and aristocrats can be "magnanimous", but ordinary citizens cannot.

Of course, by the time Churchill became involved in politics, Britain had accepted a limited democracy with most men having the vote. In the first volume of his autobiography, Churchill wrote: "All experience goes to show that once the vote has been given to everyone and what is called full democracy has been achieved, the whole political system is very speedily broken up and swept away." Churchill told his son that democracy might destroy past achievements and that future historians would probably record "that within a generation of the poor silly people all getting the votes they clamoured for they squandered the treasure which five centuries of wisdom and victory had amassed."

Winston Churchill disagreed with women having the vote. As a young man he argued: "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." His wife, Clementine Churchill, was a supporter of votes for women and after marriage he did become more sympathetic but was not convinced that it should happen. When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I have had a baby." However, at the time he was member of the Liberal Party government that had promised women the vote and could not express these opinions in public.

Churchill, as Home Secretary played a leading role in preventing women achieving the vote. Under pressure from the Women's Social and Political Union in 1911, the Liberal government introduced the Conciliation Bill that was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. However, Churchill argued in the House of Commons against the measure on the grounds that it discriminated against working-class women: "The more I study the Bill the more astonished I am that such a large number of respected Members of Parliament should have found it possible to put their names to it. And, most of all, I was astonished that Liberal and Labour Members should have associated themselves with it. It is not merely an undemocratic Bill; it is worse. It is an anti-democratic Bill. It gives an entirely unfair representation to property, as against persons.... Of the 18,000 women voters it is calculated that 90,000 are working women, earning their living. What about the other half? The basic principle of the Bill is to deny votes to those who are upon the whole the best of their sex. We are asked by the Bill to defend the proposition that a spinster of means living in the interest of man-made capital is to have a vote, and the working man's wife is to be denied a vote even if she is a wage-earner and a wife."

After leaving the Liberal Party in 1924 Churchill became Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Conservative Party government. Stanley Baldwin, the prime minister, wanted the party to develop a more liberal image and in March 1927 he suggested the enfranchisement of nearly five million women between the ages of twenty-one and thirty. This measure meant that women would constitute almost 53% of the British electorate. The Daily Mail complained that these impressionable young females would be easily manipulated by the Labour Party.

Winston Churchill was totally opposed to the move and argued that the affairs of the country ought not be put into the hands of a female majority. In order to avoid giving the vote to all adults he proposed that the vote be taken away from all men between twenty-one and thirty. Churchill lost the argument and in Cabinet and asked for a formal note of dissent to be entered in the minutes. There was little opposition in Parliament to the bill and it became law on 2nd July 1928. As a result, all women over the age of 21 could now vote in elections.

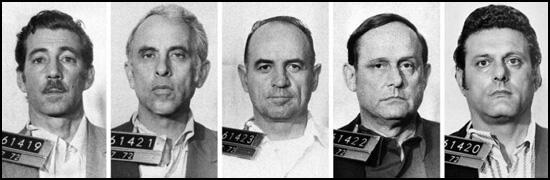

On this day in 1973 the trial of Frank Sturgis, E. Howard Hunt, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker, G. Gordon Liddy and James W. McCord began. They were all convicted of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping. On 19th March, 1973, McCord wrote a letter to Judge John J. Sirica claiming that the defendants had pleaded guilty under pressure (from John Dean and John N. Mitchell) and that perjury had been committed. Sirica decided to publish the contents of this letter. "In the interests of justice and in the interests of restoring faith in the criminal justice system, which faith has been severely damaged in this case, I will state the following to you at this time which I hope may be of help to you in meting out justice in this case. 1. There was political pressure applied to the defendants to plead guilty and remain silent. 2. Perjury occurred during the trial in matters highly material to the very structure, orientation and impact of the government's case, and to the motivation and intent of the defendants. 3. Others involved in the Watergate operation were not identified during the trial, when they could have been by those testifying."

On 30th April 1973, Richard Nixon forced two of his principal advisers H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, to resign. Richard Nixon later recalled that sacking Haldeman was "the hardest decision I had ever made." Ehrlichman did not take the decision as well as Haldemann. He had been telling Nixon for some time that he should resign. He told Nixon that day: "I have done nothing that was without your implied or direct approval." A third adviser, John Dean, refused to go and was sacked.

Bradlee was seen as partly responsible for these resignations. In his autobiography he pointed out: "April 1973 was probably the worst month ever for the Nixon White House... Magruder told the grand jury that Dean and Mitchell had approved the Watergate bugging. Acting FBI director Patrick Gray was revealed to have destroyed two folders taken from Howard Hunt's safe in the White House, immediately after the Watergate break-in, and was forced to resign in humiliation... A Wall Street Journal poll showed that a majority of Americans now believed that the president knew about the cover-up." On 12th April, The Washington Post won a Pulitzer Prize for its Watergate reporting.

On 20th April, John Dean issued a statement making it clear that he was unwilling to be a "scapegoat in the Watergate case". He told his lawyer: "I've been thinking that maybe I should go public with something. Maybe I should let them know I'm not going to take this lying down." When Dean testified on 25th June, 1973 before the Senate Committee investigating Watergate, he claimed that Richard Nixon participated in the cover-up. He also confirmed that Nixon had tape-recordings of meetings where these issues were discussed.

Ben Bradlee points out that Bob Woodward found out that Alexander Butterfield was in charge of Nixon's "internal security" and suspected he had been responsible for arranging Nixon's secret recordings. He gave this information to "an investigator on the Ervin Committee". He passed this to Samuel Dash and Butterfield was interviewed on 13th July. Late that night, Woodward received a telephone call from the investigator: "We interviewed Butterfield. He told the whole story. Nixon bugged himself." Bradlee commented in his memoirs: "The death knell of Richard Nixon was tolling."

The Special Prosecutor now demanded access to these tape-recordings. At first Nixon refused. Carl Bernstein began calling sources at the White House: "Four of them said they had learned that the tapes were of poor quality, that there were gaps in some conversations. But they did not know whether these had been caused by erasures. Ron Ziegler told Bernstein there were no gaps or erasures in the tapes. However, on 21st November, Nixon's lawyers admitted that one of the tapes had a gap of over 18 minutes.

The Supreme Court ruled against Nixon and members of the Senate began calling for him to be impeached, he changed his mind. However, some tapes were missing while others contained important gaps. Under extreme pressure, Nixon supplied tape scripts of the missing tapes.Nixon's secretary, Rose Mary Woods, denied deliberately erasing the tape. It was now clear that Nixon had been involved in the cover-up and members of the Senate began to call for his impeachment. On 9th August, 1974, Richard Nixon became the first President of the United States to resign from office. Nixon was granted a pardon but other members of his staff involved in helping in his deception were imprisoned. Nixon was granted a pardon but several members of his staff involved in the cover-up were imprisoned. This included: H. R. Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, Charles Colson, John Dean, John N. Mitchell, Jeb Magruder, Egil Krogh, Frederick LaRue, Robert Mardian and Dwight L. Chapin.

Ben Bradlee received a lot of the credit for bringing down Richard Nixon. Katharine Graham, the publisher of the The Washington Post, explained the role played by Bradlee: "Woodward and Bernstein clearly were the key reporters on the story - so much so that we began to refer to them collectively as Woodstein - but the cast of characters at the Washington Post who contributed to the story from its inception was considerable. As executive editor, Ben was the classic leader at whose desk the buck of responsibility stopped. He set the ground rules - pushing, pushing, pushing, not so subtly asking everyone to take one more step, relentlessly pursuing the story in the face of persistent accusations against us and a concerted campaign of intimidation."

Christopher Reed has pointed out: "Watergate hurt Washington, but was also cited as proof that its political system worked – eventually. It made stars of the two reporters and thrust newspaper journalism into a heroic new mould.... Bradlee embraced the truth theme fervently ... and taught courses on truth at Harvard and Georgetown universities... It was a curious stance for someone who spent many years undercover as a counter-espionage informant, a government propagandist, and unofficial asset of the Central Intelligence Agency. It started publicly enough with his Pacific war posting as a navy destroyer intelligence officer. Thereafter it became much more more clandestine."

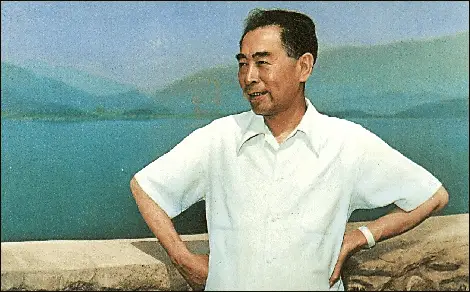

On this day in 1976 Zhou Enlai (Chou En-lai) died in Beijing. Zhou Enlai, the son of wealthy parents, was born in Jiangsu, China, in 1898. He was educated in a missionary college in Tianjin before studying at a university in Japan. He moved to France in 1920 where he helped to form the overseas branch of the Chinese Communist Party. He also lived in Britain and Germany before returning to China in 1924.

As members of the Communist Party Mao Zedong, Zhu De and Zhou Enlai adapted the ideas of Lenin who had successfully achieved a revolution in Russia in 1917. They argued that in Asia it was important to concentrate on the countryside rather than the towns, in order to create a revolutionary elite.

Zhou Enlai also worked closely with the Kuomintang and was appointed deputy director of the political department of the Whampoa Military Academy. With the help of advisers from the Soviet Union the Kuomintang gradually increased its power in China. Its leader, Sun Yat-sen died on 12th March 1925. Chiang Kai-Shek emerged as the most important figure in the organization. He now carried out a purge that eliminated the communists from the organization. Those communists who survived managed to established the Jiangxi Soviet.

The nationalists now imposed a blockade and Mao Zedong decided to evacuate the area and establish a new stronghold in the north-west of China. In October 1934 Mao, Zhou Enlai, Lin Biao, Zhu De, and some 100,000 men and their dependents headed west through mountainous areas.

The marchers experienced terrible hardships. The most notable passages included the crossing of the suspension bridge over a deep gorge at Luting (May, 1935), travelling over the Tahsueh Shan mountains (August, 1935) and the swampland of Sikang (September, 1935).

The marchers covered about fifty miles a day and reached Shensi on 20th October 1935. It is estimated that only around 30,000 survived the 8,000-mile Long March.

When the Japanese Army invaded the heartland of China in 1937, Chiang Kai-Shek was forced to move his capital from Nanking to Chungking. He lost control of the coastal regions and most of the major cities to Japan. In an effort to beat the Japanese he agreed to collaborate with Mao Zedong and his communist army.

During the Second World War the communist guerrilla forces were well led by Zhu De and Lin Biao. As soon as the Japanese surrendered, Communist forces began a war against the Nationalists led by Chaing Kai-Shek. The communists gradually gained control of the country and on 1st October, 1949, Mao Zedong announced the establishment of People's Republic of China.

Zhou Enlai became prime minister and foreign minister. In 1954 he headed the Chinese delegation to the Geneva Conference. The following year he advocated Third World unity at the Bandung Conference.

As a result of the failure on the Great Leap Forward, Mao retired from the post of chairman of the People's Republic of China. His place as head of state was taken by Liu Shaoqi. Mao remained important in determining overall policy. In the early 1960s Mao became highly critical of the foreign policy of the Soviet Union. He was for example appalled by the way Nikita Khrushchev backed down over the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Mao Zedong became openly involved in politics in 1966 when with Lin Biao he initiated the Cultural Revolution. On 3rd September, 1966, Lin Biao made a speech where he urged pupils in schools and colleges to criticize those party officials who had been influenced by the ideas of Nikita Khrushchev.

Mao was concerned by those party leaders such as Liu Shaoqi, who favoured the introduction of piecework, greater wage differentials and measures that sought to undermine collective farms and factories. In an attempt to dislodge those in power who favoured the Soviet model of communism, Mao galvanized students and young workers as his Red Guards to attack revisionists in the party. Mao told them the revolution was in danger and that they must do all they could to stop the emergence of a privileged class in China. He argued this is what had happened in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev.

Zhou Enlai at first gave his support to the campaign but became concerned when fighting broke out between the Red Guards and the revisionists. In order to achieve peace at the end of 1966 he called for an end to these attacks on party officials. Mao remained in control of the Cultural Revolution and with the support of the army was able to oust the revisionists.

Although he continued to be attacked by the Red Guards Zhou Enlai survived in power and was the main architect of the Détente policy with the United States and met Richard Nixon in China in February 1972.

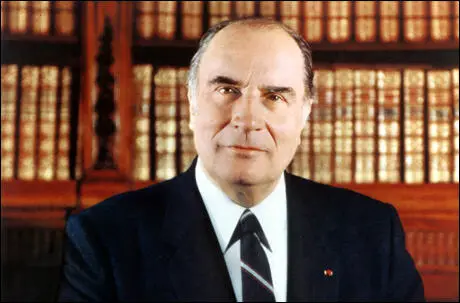

On this day in 1996 French politician Francois Mitterrand died. Mitterrand, the fifth child of a stationmaster, was born in Jarnac, France, on 26th October, 1916. An intelligent student Mitterrand studied law and political science at the University of Paris.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Mitterrand joined the French Army but in 1940 he was wounded during Germany's Western Offensive. After being captured he was taken to Germany, but managed to escape in December 1941.

Mitterrand arrived in Vichy in January 1942 and as a strong supporter of Henri-Philippe Petain was given a post in the documentation service of the Legion Francaise des Combattants. However in 1943 he broke with the government over the decision by Pierre Laval to introduce a policy of sending French workers to Germany.

He now joined the French Resistance and began working with the Organization of Armed Resistance (ORA). In November, 1943, he travelled to London where he met General Charles De Gaulle, who put him in charge of unifying the different groups representing former soldiers.

On his return to France in February 1944, Mitterrand became head of Mouvement National Des Prisonniers de Guerre. At the end of the war Mitterrand was given the job of arranging the return of the thousands of French prisoners and deportees that were still in Germany.

In 1946 was elected as a Deputy in the French National Assembly. Between 1947 and 1958 Mitterrand held ministerial posts in 11 short-lived centralists governments.

Mitterrand was opposed to the decision by Charles De Gaulle to create a Fifth Republic. This resulted in him losing his seat in the 1958 elections. His political views now became more radical and in the 1960s he began the task of building up a new, left of centre anti-Gaullist alliance, the Federation of the Left.

Mitterrand returned to the French National Assembly in 1962 and three years later was the Federation's presidential candidate and although achieving 32 per cent of the vote was defeated by Charles De Gaulle.

In 1971 Mitterrand became the leader of the Socialist Party. Over the next few years he embarked on a strategy of electoral union with the Communist Party. This proved highly successful and by 1978 it became the single most popular party in France and in 1981 Mitterrand was elected president.

As president Mitterrand introduced a series of radical economic and political reforms. This included nationalizing financial institutions and several large corporations, raising the minimum wage, improved welfare benefits and abolishing the death penalty. However, after the 1986 elections the Socialist Party lost its National Assembly majority and Mitterrand was forced to work with a right-wing coalition government.

Francois Mitterrand was re-elected president in 1988 and secured another seven year term. As the conservative parties lost their majority, a new left of centre administration was established. Worried by the economic growth of Germany, Mitterrand supported the Treaty of European Union (1991) which aimed at providing a centralized European banking system and a common currency.

In 1992 the Socialist Party suffered a crushing defeat with the right-wing parties winning 484 seats to the left's 92. Three years later Mitterrand lost the presidential election.