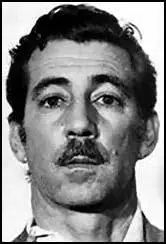

Virgilio (Villo) Gonzalez

Virgilio (Villo) Gonzalez was born in Cuba. He worked as a driver for Felipe Vidal Santiago. Both Gonzalez and Santiago moved to Miami after Fidel Castro gained power in 1959.

Gonzalez became an active member of the anti-Castro Cuban movement in the United States and associated with the Interpen (Intercontinental Penetration Force) group.

In the winter of 1962 Eddie Bayo claimed that two officers in the Red Army based in Cuba wanted to defect to the United States. Bayo added that these men wanted to pass on details about atomic warheads and missiles that were still in Cuba despite the agreement that followed the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Bayo's story was eventually taken up by several members of the anti-Castro community including Nathaniel Weyl, William Pawley, Gerry P. Hemming, John Martino, Felipe Vidal Santiago and Frank Sturgis. Pawley became convinced that it was vitally important to help get these Soviet officers out of Cuba.

William Pawley contacted Ted Shackley at JM WAVE. Shackley decided to help Pawley organize what became known as Operation Tilt. He also assigned Rip Robertson, a fellow member of the CIA in Miami, to help with the operation. David Sanchez Morales, another CIA agent, also became involved in this attempt to bring out these two Soviet officers.

In June, 1963, a small group, including Gonzalez, William Pawley, Eddie Bayo, Eugenio Martinez, Rip Robertson, John Martino, and Richard Billings, a journalist working for Life Magazine, secretly arrived in Cuba. They were unsuccessful in their attempts to find these Soviet officers and they were forced to return to Miami. Bayo remained behind and it was rumoured that he had been captured and executed. However, his death was never reported in the Cuban press.

Some researchers believe Gonzalez was involved in the assassination of John F. Kennedy. One source claims that Gonzalez was the gunman in the Dal-Tex building and Eugenio Martinez was his spotter.

On 17th June, 1972, Gonzalez, Frank Sturgis, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord were arrested while removing electronic devices from the Democratic Party campaign offices in an apartment block called Watergate. The phone number of E.Howard Hunt was found in address books of the burglars. Reporters were now able to link the break-in to the White House. Bob Woodward, a reporter working for the Washington Post was told by a friend who was employed by the government, that senior aides of President Richard Nixon, had paid the burglars to obtain information about its political opponents.

In January, 1973, Gonzalez, Frank Sturgis, E.Howard Hunt, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker, Gordon Liddy and James W. McCord were convicted of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping.

Primary Sources

(1) Several years after being imprisoned for the Watergate incident, Eugenio Martinez, wrote an account entitled Mission Impossible.

We Cubans have never stopped fighting for the liberation of our country. I have personally carried out over 350 missions to Cuba for the CIA. Some of the people I infiltrated there were caught and tortured, and some of them talked.

My mother and father were not allowed to leave Cuba. It would have been easy for me to get them out. That was my specialty. But my bosses in the Company - the CIA - said I might get caught and tortured, and if I talked I might jeopardize other operations. So my mother and father died in Cuba. That is how orders go. I follow the orders.

I can't help seeing the whole Watergate affair as a repetition of the Bay of Pigs. The invasion was a fiasco for the United States and a tragedy for the Cubans. All of the agencies of the U.S. government were involved, and they carried out their plans in so ill a manner that everyone landed in the hands of Castro - like a present.

Eduardo was a name that all of us who had participated in the Bay of Pigs knew well. He had been the maximum representative of the Kennedy administration to our people in Miami. He occupied a special place in our hearts because of a letter he had written to his chief Cuban aide and my lifelong friend, Bernard Barker. He had identified himself in his letter with the pain of the Cubans, and he blamed the Kennedy administration for not supporting us on the beaches of the Bay of Pigs.

So when Barker told me that Eduardo was coming to town and that he wanted to meet me, that was like a hope for me. He had chosen to meet us at the Bay of Pigs monument, where we commemorate our dead, on April 16, 1971, the tenth anniversary of the invasion. I always go to the monument on that day, but that year I had another purpose - to meet Eduardo, the famous Eduardo, in person.

He was different from all the other men I had met in the Company. He looked more like a politician than a man who was fighting for freedom. He was there with his pipe, relaxing in front of the memorial, and Barker introduced me. I then learned his name for the first time - Howard Hunt.

There was something strange about this man. His tan, you know, is not the tan of a man who is in the sun. His motions are very meticulous--the way he smokes his pipe, the way he looks at you and smiles. He knows how to make you happy--he's very warm, but at the same time you can sense that he does not go all into you or you all into him. We went to a Cuban restaurant for lunch and right away Eduardo told us that he had retired from the CIA in 1971 and was working for Mullen and Company.1 I knew just what he was saying. I was also officially retired from the Company. Two years before, my case officer had gathered all the men in my Company unit and handed us envelopes with retirement announcements inside. But mine was a blank paper. Afterward he explained to me that I would stop making my boat missions to Cuba but I would continue my work with the Company. He said I should become an American citizen and soon I would be given a new assignment. Not even Barker knew that I was still working with the Company. But I was quite certain that day that Eduardo knew.

We talked about the liberation of Cuba, and he assured us that "the whole thing is not over." Then he started inquiring: "What is Manolo doing?" Manolo was the leader of the Bay of Pigs operation. "What is Roman doing?" Roman was the other leader. He said he wanted to meet with the old people. It was a good sign. We did not think he had come to Miami for nothing.

Generally I talk to my CIA case officer at least twice a week and maybe on the phone another two times. I told him right away that Eduardo was back in town, and that I had had lunch with him. Any time anyone from the CIA was in town my CO always asked me what he was doing. But he didn't ask me anything about Eduardo, which was strange. That was in April. In the middle of July, Eduardo wrote to Barker to tell him he was in the White House as a counselor to the President. He sent a number of memos to us on White House stationery, and that was very impressive, you know. So I went back to my CO and said to him, "Hey, Eduardo is still in contact with us, and now he is a counselor of the President."

A few days later my CO told me that the Company had no information on Eduardo except that he was not working in the White House. Well, imagine! I knew Eduardo was in the White House. What it meant to me was that Eduardo was above them and either they weren't supposed to know what he was doing or they didn't want me to talk about him anymore. Knowing how these people act, I knew I had to be careful. So I said, well, let me keep my mouth shut.

Not long after this, Eduardo told Barker there was a job, a national security job dealing with a traitor of this country who had given papers to the Russian Embassy. He said they were forming a group with the CIA, the FBI, and all the agencies, and that it was to be directed from within the White House, with jurisdiction to operate where all the others did not fit. Barker said Eduardo needed two more individuals and he had thought of me. Would I like my name submitted for clearance? I said yes.

To me this was a great honor. I believed it was the result of my sacrifice for the previous ten years, for my work with the Company. In that time I had carried out hundreds of missions for the U.S. government. All of them had been covert, and most were very dangerous. Three or four days later, Barker told me my name had been cleared and several weeks after that came the first assignment. "Get clothes for two or three days and be ready tomorrow," he said. "We're leaving for the operation."

Barker didn't tell me where we were going and I did not ask. I was an operative. I couldn't afford to be aware of any more sensitive information than was critical for the success of my missions. There would be times when I would take men wearing hoods to Cuba. They might have been my friends. But I did not want to know. Too many of my friends have been caught and tortured and forced to talk. In this kind of work you learn to lose your curiosity.

So it was not until I got to the airport in Miami that I discovered we were going to Los Angeles. There were three of us on the mission. The third man, Felipe de Diego, was a real-estate partner of ours. He is an old Company man and a Bay of Pigs veteran whom we knew we could trust.

In all my years in this country I had never been out of the Miami area before that day. I had always been on twenty-four-hour call. I kind of expected my CO to ask where I was going, but he simply said it was fine for me to take a few days off, that there wasn't much to do at the time. I sort of thought he did not want to know what I was doing.

We stayed at the Beverly Hills Hotel and met in Eduardo's room for our only briefing. As we walked in I noticed the equipment - devices to modify the voice, wigs and fake glasses, false identification. Eduardo told us all these things belonged to the Company. Barker recognized the name on Hunt's false identification - Edward J. Hamilton - as the same cover name Eduardo had used during the Bay of Pigs.

The briefing was not like anything I was used to in the Company. Ordinarily, before an operation, you have a briefing and then you train for the operation. You try to find a place that looks similar and you train in disguise and with the code you are going to use. You try out the plan many times so that later you have the elasticity to abort the operation if the conditions are not ideal.

Eduardo's briefing was not like this. There wasn't a written plan, not even any mention of what to do if something went wrong. There was just the man talking about the thing. We were to get into an office to take photographs of psychiatric records of a traitor. I was to be the photographer. The next day we went to Sears and bought some little hats and uniforms for Barker and Felipe. They were supposed to dress up as delivery men and deliver the photographic equipment inside the office. Later that night we would break in and complete the mission.

They looked kind of queerish when they put on the clothes, the Peter Lorre-type glasses, and the funny Dita Beard wigs. But that was not my responsibility, so I waited in the car while they went to the office of Dr. Fielding to deliver the package. Just before leaving Barker had whispered to me: "Hey, remember this name - Ellsberg." Eduardo had told him the name, and he told me because he was worried he would forget it. The name meant nothing to me.

Barker and Felipe were supposed to put the bag inside the office, unlatch the back door, and come out. After the cleaning lady left, we were to go back in. Now, it happened that we had to wait for hours and hours because no one had figured out when the cleaning woman would leave. Finally, I believe, a gentleman came in a car and picked her up.

So at last we went to open the door - and what happened? The door was locked. Barker went around to see if the other door was open, and after a long wait he still did not show up. We didn't know what to do. There had been another man in the briefing the night before in Eduardo's room who hadn't said anything. Later, I learned it was probably Gordon Liddy, but at the time I only knew him as George. Just at that moment, he came up to us and said, "Okay, you people go ahead and force one of the windows and go in."

Eduardo had given us a small crowbar and a glass cutter. I tried to cut the glass, but it wouldn't cut. It was bad, bad. It would not cut anything! So then I taped the window and I hit it with this very small crowbar, and I put my hand in and unlocked the window.

According to the police, we were using gloves and didn't leave any fingerprints. But I'm afraid that I did because I didn't wear my gloves when I put the tape on the window - you know, sometimes it's hard to use gloves. I went all through the offices with my bare hands but I used my handkerchief to wipe off the prints.

Inside the doctor's office we covered the windows and took out the equipment. Really, it was a joke. They had given us a rope to bail out from the second floor if anyone surprised us; it was so small, it couldn't have supported any of us.

This was nothing new. It's what the Company did in the Bay of Pigs when they gave us old ships, old planes, old weapons. They explained that if you were caught in one of those operations with commercial weapons that you could buy anywhere, you could be said to be on your own. They teach you that they are going to disavow you. The Company teaches you to accept those things as the efficient way to work. And we were grateful. Otherwise we wouldn't have had any help at all. In this operation it seemed obvious - they didn't want it to be traced back to the White House. Eduardo told us that if we were caught, we should say we were addicts looking for drugs.

I had just set up the photographic equipment when we heard a noise. We were afraid. Then we heard Barker's familiar knock and we let him in. I took a Polaroid picture of the office before we started looking for the Ellsberg papers so we could put everything back just as it was before. But there was nothing of Ellsberg's there. There was nothing about psychiatry, no one file of sick people, only bills. It looked like an import-export office more than a psychiatrist's. The only thing with the name of Ellsberg in it was the doctor's telephone book. I took a photo of this so that we could bring something back. Before leaving I took some pills from Dr. Fielding's briefcase--vitamin C, I think--and spread them all over the floor to make it look like we were looking for drugs. Eduardo was waiting for us outside. He was supposed to be keeping watch on Dr. Fielding so he could let us know if the doctor was returning to his office, but Eduardo had lost Dr. Fielding and he was nervous. A police car appeared as we drove away and it trailed behind us for three or four blocks. I thought to myself that the police car was protecting us. That is the feeling you have when you are doing operations for the government. You think that every step has been taken to protect you.

Back at the hotel, Barker, Felipe, and I felt very bad. It was our first opportunity, and we had failed; we hadn't found anything. "Yes, I know, but they don't know it," Eduardo said, and he congratulated us all. He said, "Well done," and then he opened a bottle of champagne. And he told us, "This is a celebration. You deserve it."

I told Diego and Barker that this had to have been a training mission for a very important mission to come or else it was a cover operation. I thought to myself that maybe these people already had the papers of Ellsberg. Maybe Dr. Fielding had given them out and for ethical reasons he needed to be covered. It seemed that these people already had what we were looking for because no one invites you to have champagne and is happy when you fail.

The whole thing was strange, but Eduardo was happy so we were happy. He thanked us and we left for the airport. We took the plane back to Miami and we never talked about this thing until we were all together in the District of Columbia jail. In Miami I again told my CO about Eduardo. I was certain then that the Company knew about his activities. But once again my CO did not pursue the subject.

Meanwhile, Hunt started to do more and more things that convinced us of his important position in the White House. Once he called Barker and told him the President was about to mine Haiphong Harbor. He asked us to prepare letters and a rally of support in advance. It was very impressive to us when the announcement of the mining was made several days later.

I made a point of telling my CO at our next meeting that Hunt was involved in some operations and that he was in the White House, even if they said he wasn't. After that the CIA chief of the Western Hemisphere asked me for breakfast at Howard Johnson's on Biscayne Boulevard, and he said he was interested in finding out about Howard Hunt's activities. He wanted me to write a report. He said I should write it in my own hand, in Spanish, and give it to my CO in a sealed envelope. Right away I went to see my CO. We are very close, my CO and I, and he told me that his father had once given him the advice that he should never put anything in writing that might do him any harm in the future. So I just wrote a cover story for the whole thing. I said that Hunt was in the Mullen Company and the White House and things like that that weren't important. What I really thought was that Hunt was checking to see if I could be trusted.

Little by little I watched Eduardo's operation grow. First Barker was given $89,000 in checks from Mexican banks to cash for operational money. And then Eduardo told Barker to recruit three more men, including a key man. He signed up Frank Sturgis and Reinaldo Pico, and then Eduardo flew down to talk to our friend Virgilio Gonzales, who is a locksmith, before recruiting him. Finally orders come for us to report to Washington. The six of us arrived in Washington on May 22 and checked into the Manger Hay-Adams Hotel in time for Eduardo's first briefing.

By that time Liddy, whom we had known as George from the Fielding break-in, was taking a visible role in the planning. Eduardo had started calling him "Daddy," and the two men seemed almost inseparable. We met McCord there for the first time. Eduardo said he was an old man from the CIA who used to do electronic jobs for the CIA and the FBI. We did not know his whole name. Eduardo just introduced him as Jimmy. He said we would be using walkie-talkies, and Jimmy was to be our electronics expert. There was also a boy there who had infiltrated the McGovern headquarters.

There was no mention of Watergate at that meeting. Eduardo told us he had information that Castro and other foreign governments were giving money to McGovern, and we were going to find the evidence. The boy was going to help them break into the McGovern headquarters, but I did not pay much attention. They didn't need me for that operation so I had some free time.

During the day I went off to see the different sights around Washington. I like those things--particularly the John Paul Jones monument and the Naval Academy in Annapolis. Remember that, prior to this, all of my operations for the United States were maritime. After three days Eduardo aborted the McGovern operation. I think it was because the boy got scared. Anyway, Eduardo told us all to move into the Watergate Hotel to prepare for another operation. We brought briefcases and things like that to look elegant. We registered as members of the Ameritus Corporation of Miami, and then we met in Eduardo's room.

Believe me, it was an improvised briefing. Eduardo told us he had information that Castro money was coming into the Democratic headquarters, not McGovern's, and that we were going to try to find the evidence there. Throughout the briefing, McCord, Liddy, and Eduardo would keep interrupting each other, saying, "Well, this way is better," or, "That should be the other way around."

It was not a very definite plan that was finally agreed upon, but you are not too critical of things when you think that people over you know what they are doing, when they are really professionals like Howard Hunt. The plan called for us to hold a banquet for the Ameritus Corporation in a private dining room of the Watergate. The room had access to the elevators that ran up to the sixth floor where the Democratic National Committee Headquarters are located. Once the meal was underway, Eduardo was to show films and we were to take the elevator to the sixth floor and complete the mission. Gonzales, our key man, was to open the door; Sturgis, Pico, and Felipe were to be lookouts; Barker was to get the documents; I was to take the photographs and Jimmy (McCord) was to do his job.

We were all ready to go, but the people in the DNC worked late. Eduardo was drinking lots of milk. He has ulcers, so he was mixing his whiskey with the milk. We waited and waited. Finally, at 2:00 a.m., the night guards said we had to leave the banquet hall. So then there was a discussion. Eduardo said he would hide in the closet of the banquet room with Gonzales, the key man, while the guard let the rest of us out. As soon as the coast was clear, they would let us back in. But then they couldn't open the door. It is difficult for me to tell you this story. I do not want it to become a laughing matter. More than thirty people are in jail already, and a lot of people are suffering. I spent more than fifteen months in jail, and you must understand that this is a tragedy. It is not funny. But you can imagine Eduardo, the head of the mission, in the closet. He did not sleep the whole night. It was really a disaster.

So, more briefings, and we decided to go the next night. This time the plan was to wait until all the lights had gone out on the sixth floor of the Watergate and then go in through the front door.

They gave us briefcases, and I remember that there was a Customs tag hanging on Eduardo's case, so I pulled it off for him. He got real mad. He said that every time he did something he did it with a purpose. I could not see the purpose, but then I don't know. Maybe the tag had an open sesame command to let us in the doors.

Anyway, all seven of us in McCord's army walked up to the Watergate complex at midnight. McCord rang the bell, and a policeman came and let us in. We all signed the book, and McCord told the man we were going to the Federal Reserve office on the eighth floor. It all seemed funny to me. Eight men going to work at midnight. Imagine, we sat there talking to the police. Then we went up to the eighth floor, walked down to the sixth--and do you believe it, we couldn't open that door, and we had to cancel the operation.

I don't believe it has ever been told before, but all the time while we were working on the door, McCord would be going to the eighth floor. It is still a mystery to me what he was doing there. At 2:00 a.m. I went up to tell him about our problems, and there I saw him talking to two guards. What happened? I thought. Have we been caught? No, he knew the guards. So I did not ask questions, but I thought maybe McCord was working there. It was the only thing that made sense. He was the one who led us to the place and it would not have made sense for us to have rooms at the Watergate and go on this operation if there was not someone there on the inside. Anyway, I joined the group, and pretty soon we picked up our briefcases and walked out the front door.

Eduardo was furious that Gonzales hadn't been able to open the door. Gonzales explained he didn't have the proper equipment, so Eduardo told him to fly back to Miami to get his other tools. Before he left the next day, Barker told Gonzales that he might have to pay for his own flight back to Miami. I really got mad and told Barker I resented the way they were treating Gonzales. I was a little hard with Barker. I said there wasn't adequate operational preparation. There was no floor plan of the building; no one knew the disposition of the elevators, how many guards there were, or even what time the guards checked the building. Gonzales did not know what kind of door he was supposed to open. There weren't even any contingency plans.

Barker came back to me with a message from Eduardo: "You are an operative. Your mission is to do what you are told and not to ask questions."

Gonzales got back from Miami that night with his whole shop. I've never seen so many tools to open a door. No door could hold him. This time everything worked. Gonzales and Sturgis picked the lock in the garage exit door; once inside, they opened the other doors and called over the walkie-talkie: "The horse is in the house." Then they let us in. I took a lot of photographs--maybe thirty or forty--showing lists of contributors that Barker had handed me. McCord worked on the phones. He said his first two taps might be discovered, but not the third.

With our mission accomplished, we went back to the hotel. It was about 5:00 a.m. Eduardo said he was happy. But this time there was no champagne. He said we should leave for Miami right away. I gave him the film I had taken and we left for the airport. There were things that bothered me about the operation, but I was satisfied. It is rare that you are able to check the effect of your work in the intelligence community. You know, they don't tell you if something you did is very significant. But we had taken a lot of pictures of contributions, and I had hopes that we might have done something valuable. We all had heard rumors in Miami that McGovern was receiving money from Castro. That was nothing new. We believe that today.

A couple of weeks later I was talking with Felipe de Diego and Frank Sturgis at our real-estate office when Barker burst in like a cyclone. Eduardo had been in town, and he had given Barker some film to have developed and enlarged. Barker did not know what the film was, and he had taken it to a regular camera shop. And then Eduardo had told him it was the film from the Watergate operation. Barker was really excited. He needed us to come with him to get it back. So we went to Rich's Camera Shop, and Barker told Frank and me to cover each door to the shop in case the police came while he was inside. I do not think he handled the situation very well. There were all these people and he was so excited. He ended up tipping the man at the store $20 or $30. The man had just enlarged the pictures showing the documents being held by a gloved hand and he said to Barker: "It's real cloak-and-dagger stuff, isn't it?" Later that man went to the FBI and told them about the film.

My reaction was that it was crazy to have those important pictures developed in a common place in Miami. But Barker was my close friend, and I could not tell him how wrong the whole thing was. The thing about Barker was that he trusted Eduardo totally. He had been his principal assistant at the Bay of Pigs, Eduardo's liaison with the Cubans, and he still believed tremendously in the man. He was just blind about him.

It was too much for me. I talked it over with Felipe and Frank, and decided I could not continue. I was about to write a letter when Barker told me Eduardo wanted us to get ready for another operation in Washington.

When you are in this kind of business, and you are in the middle of something, it is not easy to stop. Everyone will feel that you might jeopardize the operation. "What to do with this guy now?" I knew it would create a big problem so I agreed to go on this last mission.

Eduardo told us to buy surgical gloves and forty rolls of film with thirty-six exposures on a roll. Imagine, that meant 1,440 photographs. I told Barker it would be impossible to take all those pictures. But it did seem to mean that what we got before encouraged Eduardo to go back for more.

We flew into National Airport about noon on June 16, and Barker and I went off to rent a car. In the airport lobby, Frank Sturgis ran into Jack Anderson, whom he had known since the Bay of Pigs, when Anderson wrote a column about him as a soldier-adventurer. Frank introduced Gonzales to Anderson, and he gave him some kind of excuse about why he was in town.

On our way to the Watergate, we made some jokes about the car Barker had rented. It gave me a premonition of a hearse. The mission was not one I was looking forward to.

Eduardo was waiting for us at the Watergate. This time he had two operations planned, and we were supposed to perform them both that night. There was no time for anything, it was all rush.

We went to eat at about five o'clock. Barker ate a lot and when he came back he felt really bad. I was not feeling too good myself. I had just gotten my divorce that day and had gone from the court to the airport and from the airport to the Watergate. The environment in each one of us was different, but the whole thing was bad; there was tension in those people.

Liddy was already in the room when Eduardo came in to give the briefing. Eduardo was wearing loafers and black pants with white stripes. They were very shiny. Liddy was not happy with those pants. He criticized them in front of us and he told Eduardo to go change them.

So Eduardo went and changed his pants. The briefing he gave when he came back was very simple. He said we were going to photograph more documents at the Democratic headquarters and then move on to another mission at the McGovern headquarters after that. McCord was critical of the second operation. He said he didn't like the plan. It was very rare to hear McCord talking because usually he didn't say anything and when he did talk he only whispered.

Before we left, Eduardo took all of our identification. He put it in a briefcase and left it in our room. He gave Sturgis his Edward J. Hamilton identification that the CIA had provided to him before, and he gave us each $200 in cash. He said we should use it as a bribe to get away if we were caught. Finally, he told us to keep the keys to our room, where he had left the identification. I don't know why. Even today, I don't know. Remember, I was told in advance not to ask about those things.

McCord went into the Watergate very early in the evening. He walked right through the front door of the office complex, signed the book, and, I'm sure, went to the eighth floor as he had before. Then he taped the doors from the eighth floor to the bottom floor and walked out through the exit door in the garage. It was still very early, and we were not going to go in until after everyone left the offices. We waited so long that Eduardo went out to check if the tapes were still there. He said they were but when we finally got ready to go in, Virgilio and Sturgis noticed that the tape was gone, and a sack of mail was at the door.

So we said, well, the tape has been discovered. We'll have to abort the operation. But McCord thought we should go anyway. He went upstairs and tried to convince Liddy and Eduardo that we should go ahead. Before making a decision, they went to the other room.

I believe they made a phone call, and Eduardo told us to go ahead. McCord did not come in with us. He said he had to go someplace. We never knew where he was going. Anyway, he was not with us, so when Virgilio picked the locks to let us in, we put tape on the doors for him and went upstairs. Five minutes later McCord came in, and I asked him right away: "Did you remove the tapes?" He said, "Yes, I did."

But he did not, because the tape was later found by the police. Once inside, McCord told Barker to turn off his walkie-talkie. He said there was too much static. So we were there without communications. Soon we started hearing noises. People going up and down. McCord said it was only the people checking, like before, but then there was running and men shouting, "Come out with your hands up or we will shoot!" and things like that. There was no way out. We were caught. The police were very rough with us, pushing us around, tying our arms, but Barker was able to turn on his walkie-talkie, and he asked where the police were from. And then he said, "Oh, you are the metropolitan policemen who catch us." So Barker was cool. He did a good job in advising Eduardo we were caught.

I thought right away it was a set-up or something like that because it was so easy the first time. We all had that feeling. They took our keys and found the identification in the briefcase Eduardo had left in our room.

McCord was the senior officer, and he took charge. He was talking loudly now. He told us not to say a thing. "Don't give your names. Nothing. I know people. Don't worry, someone will come and everything will be all right. This thing will be solved."