On this day on 7th May

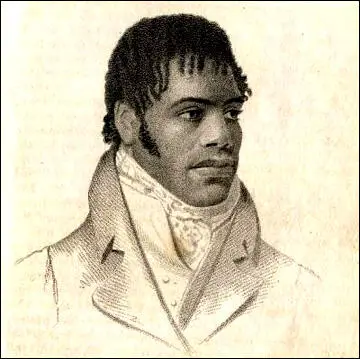

On this day in 1820 the British Luminary and Weekly Intelligence report on the execution of William Davidson. "Davidson ascended the scaffold with a firm step, calm deportment, and undismayed countenance. He bowed to the crowd, but his conduct altogether was equally free from the appearance of terror, and the affectation of indifference."

William Davidson, was born in Jamaica in 1781. The illegitimate son of the Jamaican Attorney General and a local black woman, William was sent to Glasgow at the age of fourteen to study law. While in Scotland he became involved in the demand for parliamentary reform. Davidson was apprenticed to a Liverpool lawyer but after three years ran away to sea. Later he was impressed into the Royal Navy.

On his discharge he returned to Scotland and his father sent him to study mathematics in Aberdeen. Davidson did not enjoy his studies and moved to Birmingham where he started a cabinet-making business. Davidson fell in love with the daughter of a prosperous merchant. The father disapproved of his daughter's relationship and suspected that Davidson was after her £7,000 dowry and arranged for him to be arrested on a false charge. When he discovered she had married someone else he tried to kill himself by taking poison.

After the failure of his cabinet-making business William Davidson moved to London. He married Sarah Lane, a working-class widow with four children. In the next few years she had two more. Davidson became a Wesleyan Methodist and taught at the local Sunday School. This came to an end when he was accused of attempting to seduce a female student.

William Davidson became involved in radical politics again after the Peterloo Massacre. After Richard Carlile was found guilty of blasphemy and seditious libel and sentenced to three years imprisonment in October 1819, Davidson told a friend that these events had caused him to lose his belief in God. Davidson now joined the Marylebone Union Reading Society where for twopence a week he was able to read radical newspapers such as the Republican and the Manchester Observer. He also read the works of Tom Paine.

It was at the Marylebone Union that Davidson met John Harrison, a member of the Spencean Philanthropists in London. Soon afterwards Davidson also became a Spencean. He met Arthur Thistlewood and within a few months became one of the Committee of Thirteen that ran the organisation.

On 22nd February 1820, George Edwards (a government spy) pointed out to Arthur Thistlewood an item in the New Times that several members of the British government were going to have dinner at Lord Harrowby's house at 39 Grosvenor Square. William Davidson agreed to join Thistlewood and and twenty-seven other Spenceans in the plot to kill the government ministers dining at Lord Harrowby's house on 23rd February. Thistlewood selected Davidson as one of the Executive of Five whose job it was to organise the assassinations.

Davidson had worked for Lord Harrowby in the past and knew some of the staff that worked at Grosvenor Square. He was instructed to find out more details about the cabinet meeting. However, when he spoke to one of the servants he was told that the Earl of Harrowby was not in London. When Davidson reported this news back to Arthur Thistlewood he insisted that the servant was lying and that the assassinations should proceed as planned.

On the 23rd February Thistlewood's gang assembled in a hayloft in Cato Street, a short distance away from Grosvenor Square. However, government ministers were not meeting at the home of Earl of Harrowby. The Spenceans had been set up by George Edwards, a government spy who had infiltrated the Spencean Society.

Thirteen police officers led by George Ruthven stormed the hay loft. Several members of the gang refused to surrender their weapons and one police officer, Richard Smithers, was killed by Arthur Thistlewood. Davidson attempted to fight his way out but Benjamin Gill hit him on the wrist with his truncheon and he dropped his blunderbuss. Four of the conspirators, Thistlewood, John Brunt, Robert Adams and John Harrison escaped out of a window. However, George Edwards had given the police a detailed list of all those involved and the men were soon arrested.

Eleven men were eventually charged with being involved in the Cato Street Conspiracy. Charges against Robert Adams were dropped when he agreed to give evidence against the other men in court. Davidson claimed he was innocent and accused the court of being prejudiced against black people. However, not only had Davidson been arrested at the scene but evidence was produced to show that he had taken a blunderbuss out of pawn to use in the attempted assassinations.

Davidson said in court: "It is an ancient custom to resist tyranny... And our history goes on further to say, that when another of their Majesties the Kings of England tried to infringe upon those rights, the people armed, and told him that if he did not give them the privileges of Englishmen, they would compel him by the point of the sword... Would you not rather govern a country of spirited men, than cowards? I can die but once in this world, and the only regret left is, that I have a large family of small children, and when I think of that, it unmans me."

On 28th April 1820, William Davidson, James Ings, Richard Tidd, Arthur Thistlewood, and John Brunt were found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death. John Harrison, James Wilson, Richard Bradburn, John Strange and Charles Copper were also found guilty but their original sentence of execution was subsequently commuted to transportation for life. William Davidson was executed at Newgate Prison on the 1st May, 1820.

On this day in 1832 the House of Lords rejected the government parliamentary reform act. On 22nd September 1831, the House of Commons passed the Reform Bill. However, the Tories still dominated the House of Lords, and after a long debate the bill was defeated on 8th October by forty-one votes. When people heard the news, Reform Riots took place in several British towns; the most serious of these being in Bristol in October 1831, when all four of the city's prisons were burned to the ground. Several people were killed by troops and four of reform leaders were executed. In London, the houses owned by the Duke of Wellington and bishops who had voted against the bill in the Lords were attacked. On 5th November, Guy Fawkes was replaced on the bonfires by effigies of Wellington.

Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, complained: "This detestable Reform Bill has raised the hopes of the utmost. At Plymouth and the neighbouring towns, the spirit is tremendously bad. The shopkeepers are almost all Dissenters, and such is the rage on the question of Reform at Plymouth, that I have received from several quarters the most earnest requests that I will not come to concentrate a church, as I had engaged to do. They assure me that my own person, and the security of the public peace, would be in the greatest danger."

Earl Grey argued in the House of Commons that without reform he feared a violent revolution would take place: "There is no one more decided against annual parliaments, universal suffrage, and the ballot, than I am. My object is not to favour but to put an end to such hopes and projects." The Poor Man's Guardian agreed and it commented that the ruling class felt that "a violent revolution is their greatest dread".

Grey attempted negotiation with a group of moderate Tory peers, known as "the waverers", but failed to win them over. On 7th May a wrecking amendment was carried by thirty-five votes, and on the following day the cabinet resolved to resign unless the king would agree to the creation of peers. On 7th May 1832, Earl Grey and Henry Brougham met the king and asked him to create a large number of Whig peers in order to get the Reform Bill passed in the House of Lords. William was now having doubts about the wisdom of parliamentary reform and refused.

On this day in 1837 Mary Hogarth dies suddenly after a visit to the theatre. Mary Hogarth was born in Edinburgh in 1819. Mary was one of ten children, including Catherine Hogarth (1815) and Georgina Hogarth (1827). Her father, George Hogarth, was a talented writer and worked as a journalist for the Edinburgh Courant.

In 1830 Hogarth and his family moved to London in order to develop his career as a writer. Claire Tomalin has argued: "He decided to move south, using his knowledge of music and literature to help him find work as a journalist and critic. At first he worked for Harmonicon . In 1831 Hogarth went to Exeter to edit the tory Western Luminary , and in the following year he moved to Halifax as the first editor of the Halifax Guardian. He supplemented his income by doing some teaching in the town.

In 1834 George Hogarth returned to London and was engaged by the The Morning Chronicle as a writer on political and musical subjects. The following year he was appointed as editor of The Evening Chronicle . He became friends with Charles Dickens and commissioned him to write a series of stories under the pseudonym "Boz".

Hogarth invited Dickens to visit him at his home in Kensington. The author of Dickens: A Life (2011) has pointed out: "Hogarth... had a large and still growing family, and when he (Dickens) made his first visit to their house on the Fulham Road, surrounded by gardens and orchards, he met their eldest daughter, nineteen-year-old Catherine. Her unaffectedness appealed to him at once, and her being different from the young woman he had known, not only in being Scottish but in coming from an educated family background with literary connections. The Hogarths, like the Beadnells, were a cut above the Dickens family, but they welcomed Dickens warmly as an equal, and George Hogarth's enthusiasm for his work was flattering."

Mary Hogarth was only fourteen when she met Dickens. Peter Ackroyd has pointed out: "Mary was not yet of an age to marry but there is no doubt that the affection between her and the younger Dickens was strong; she gave him presents, a fruit knife and silver inkwell, very soon after he had come to know the Hogarths and it is clear from all later reports that her gentle and selfless nature deeply impressed the young man."

Charles Dickens married Catherine Hogarth on 2nd April, 1836, at Lukes Church, Chelsea. After a wedding breakfast at her parents, they went on honeymoon to the village of Chalk, near Gravesend. Dickens wanted to show Catherine the countryside of his childhood. However, he discovered that his wife did not share his passion for long, fast walks. As one biographer put it: "Writing was necessarily his primary occupation, and hers must be to please him as best she could within the limitations of her energy: writing desk and walking boots for him, sofa and domesticity for her."

The couple lived in Furnival's Inn where Dickens had rented three rooms. Mary moved in with them when the arrived back after their honeymoon. She stayed for a month but friends said that she always seemed be with Catherine in her new home. Dickens later wrote: "From the day of our marriage, the dear girl had been the grace and life of our home, our constant companion, and the sharer of all our little pleasures."

Mary Hogarth wrote to her cousin describing Catherine as "a most capital house-keeper... happy as the day is long". She added: "I think they are more devoted than ever since their marriage if that be possible - I am sure you would be delighted with him if you knew him he is such a nice creature and so clever he is courted and made up to by all literary gentlemen, and has more to do in that way than he can well manage."

Catherine Dickens had her first child, Charles Culliford Dickens, in January, 1837. She had difficulty feeding the baby and gave up trying. A wet nurse was found but Mary believed that her sister was suffering from depression: "Every time she (Catherine) sees her baby she has a fit of crying and keeps constantly saying she is sure he (Charles Dickens) will not care for her now she is not able to nurse him."

Dickens now travelled around London with Mary to find a new home. On 18th March he made an offer for 48 Doughty Street. After agreeing to a rent of £80 a year, they moved in two weeks later. Situated in a private road with a gateway and porter at each end. It had twelve rooms on four floors. Mary had one of the bedrooms on the second floor. Dickens employed a cook, a housemaid, a nurse, and later, a manservant.

During this period Mary was greatly admired by men who met her. John Strang commented that "she is a sweet interesting creature" and would not be surprised if "some two-legged monster does not carry her off". The poet, Robert Story described Mary Hogarth as the "fairest flower of spring" but also compared her glances to those of a falcon.

On 6th May, 1837, Charles, Catherine and Mary went to the St James's Theatre to see the play, Is She His Wife ? They went to bed at about one in the morning. Mary went to her room but, before she could undress, gave a cry and collapsed. A doctor was called but was unable to help. Dickens later recalled: "Mary... died in such a calm and gentle sleep, that although I had held her in my arms for some time before, when she was certainly living (for she swallowed a little brandy from my hand) I continued to support her lifeless form, long after her soul had fled to Heaven. This was about three o'clock on the Sunday afternoon." Dickens later recalled: "Thank God she died in my arms and the very last words she whispered were of me." The doctor who treated her believed that she must have had undiagnosed heart problems. Catherine was so shocked by the death of her younger sister that she suffered a miscarriage a few days later.

Peter Ackroyd has argued: "His grief was so intense, in fact, that it represented the most powerful sense of loss and pain he was ever to experience. The deaths of his own parents and children were not to affect him half so much and in his mood of obsessive pain, amounting almost to hysteria, one senses the essential strangeness of the man... It has been surmised that all along Dickens had felt a passionate attachment for her and that her death seemed to him some form of retribution for his unannounced sexual desire - that he had, in a sense, killed her."

Charles Dickens cut off a lock of Mary's hair and kept it in a special case. He also took a ring off her finger and put it on his own, and there it stayed for the rest of his life. Dickens also expressed a wish to be buried with her in the same grave. He also kept all of Mary's clothes and said a couple of years later that "they will moulder away in their secret places". Dickens wrote that he consoled himself "above all... by the thought of one day joining her again where sorrow and separation are unknown". He was so upset by Mary's death that for the first and last time in his life he missed his deadlines and the episodes of The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist which were supposed to be written during that month were postponed.

Dickens told his friend, Thomas Beard: "So perfect a creature never breathed. I knew her inmost heart, and her real worth and values. She had not a fault." He told other friend that "every night she appeared in his dreams". Michael Slater, the author of Charles Dickens: A life Defined by Writing (2011) has suggested: "It was the third great emotional crisis of his life, following the blacking factory experience and the Beadnell affair, and one that profoundly influenced him as an artist as well as a man."

Philip V. Allingham has argued: "Critics and biographers... have written extensively on the massive influence that the memory of the dead seventeen-year-old Scottish girl exerted upon Dickens throughout his career... As numerous critics have noted, Mary probably served Dickens as the basis - the spiritual essence, as it were - of Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop (the child-character's death in January 1841 brought back the pain of Dickens's parting from his sister-in-law on Sunday, 7 May 1837), of Rose Maylie in Oliver Twist, of the protagonist's seventeen-year-old sister Kate in Nicholas Nickleby, and of Agnes in David Copperfield."

In 1841 Mary's brother, George Hogarth, died suddenly. It was decided that he should be buried in the same grave as his sister. Charles Dickens was intensely distressed by the news and told John Forster that "it seems like losing her for a second time".

On this day in 1845 Mary Mahoney was born in Dorchester, Massachusetts. At eighteen Mahoney found work at the New England Hospital for Women and Children. For the next fifteen years she was employed as a cook and cleaner and it was not until 1878 that she was accepted as a student nurse. Training was rigorous and of the forty-two students accepted in 1878, only four, including Mahoney, graduated.

Mahoney developed a reputation as an outstanding nurse and was asked to look after private patients in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Washington and North Carolina. Her successful career played an important role in overcoming the considerable racial prejudice against African American nurses that existed at this time.

Mahoney became one of the first African-American women to join the American Nurses Association. In an attempt to combat racial discrimination in nursing, Mahoney joined with Martha Franklin and Adah Thoms to establish the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN). A deeply religious woman, Mahoney became the NACGN national chaplain.

In 1911 Mahoney moved to New York where she took charge of the Howard Orphan Asylum for Black Children in Kings Park, Long Island.

Mahoney was a strong supporter of women's suffrage and in 1921, aged seventy-six, was one of the first women in Boston to register to vote after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Mary Mahoney died of breast cancer on 4th January, 1926, and is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Everett, Massachusetts.

On this day in 1847 Archibald Primrose was born in London. Educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, he became the 5th Earl of Rosebery after the death of his grandfather in 1868. Rosebery was a supporter of the Liberal Party in the House of Lords and supported social reform.

After the 1880 General Election, the Prime Minister, William Gladstone, appointed Rosebery as his under-secretary for the home department and in 1884 he became commissioner of works in his government. Further promotion was achieved in 1886 when Gladstone gave him the important job of Foreign Secretary.

The 1885 General Election returned a Conservative government and Rosebery was now on the opposition benches. Rosebery turned his attention to local government and in 1889 became chairman of the recently established London County Council.

After the 1892 General Election, the Liberal Prime Minister, William Gladstone, appointed Rosebery as his Foreign Secretary. When Gladstone resigned two years later he suggested to Queen Victoria that she appointed the Earl of Rosebery as Prime Minister. His period in power was only short as the Liberal Party was defeated in the 1895 General Election.

Rosebery led the Liberal Party until he resigned in 1896. He was an imperialist during the Boer War and gradually moved away from his earlier progressive views. In debates in the House of Lords he tended to support and vote with the Conservatives. Archibald Primrose, the 5th Earl of Rosebery died on 21st May, 1929.

On this day in 1864 Catherine Pine was born in Maidstone. She trained as a nurse at St Bartholomew's Hospital from 1895 until 1897. After qualifying she remained at St Bartholomew's and in 1900 she was promoted to hospital sister. In 1901 she moved to Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Pine joined the Women Social & Political Union and she was involved with Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson in running the Notting Hill nursing home that WSPU members went to while recovering from hunger strikes. She also treated Harry Pankhurst, the son of Emmeline Pankhurst. Harry died in the nursing home in January 1910.

On 13th October 1913 she attended a meeting being addressed by Sylvia Pankhurst at Bow Baths Hall. Pine was injured in a struggle with the police during the meeting. Pine was devoted to Emmeline Pankhurst and was her personal nurse after she was released from Holloway Prison in 1913.

According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "Nurse Pine's own nursing home was so besieged by detectives and onlookers that, in order to maintain the calm necessary to the recovery of her patients and in order that she should not lose clients and thereby jeopardize her business, Nurse Pine looked after Mrs Pankhurst, in London." Pine therefore looked after Pankhurst in the homes of Hertha Ayrton, Ethel Smyth and Hilda Brackenbury.

During the First World War she set up a hostel in which to care for illegitimate "war babies". It was housed first in Mecklenburgh Square and then at 50 Clarendon Road. After the war Pine accompanied Pankhurst to USA and Canada. Pine returned to England in 1923.

Catherine Pine died on 14th August 1941.

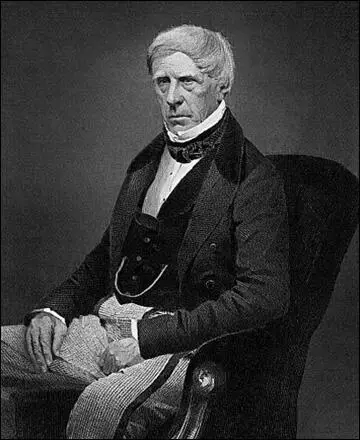

On this day in 1868 Henry Brougham, died at Château Eleanor-Louise, Cannes, and was buried on 24th May in the town's cemetery.

Henry Brougham, the eldest son of Henry Brougham (1742–1810) and Eleanora Syme Brougham, was born in Edinburgh on 19th September, 1778. Brougham was a modest landowner in Westmorland. At the age of seven he was sent to the local high school.

Henry, was extremely intelligent and was accepted as a student at the University of Edinburgh at the age of 14. At first Brougham studied science and mathematics and while still a student presented a paper Experiments and Observations of the Infection, Reflection and Colours of Light, to the Royal Society. Brougham became interested in law and in 1800 joined the university's faculty of advocates.

His biographer, Michael Lobban has argued: "Brougham was called to the Scottish bar in June 1800, and went directly on the summer circuit. His early experience of life as a lawyer was not a happy one. Although he enjoyed the scope which advocacy gave to his rhetorical skills, and used them daringly to spar with and irritate judges, his showmanship attracted no more than the occasional poor client. Brougham was soon disgusted with law, and resented it for interfering with his politics."

In 1802 Brougham and a few friends founded the journal Edinburgh Review. In the next two years Brougham contributed thirty-five articles. At university Brougham developed radical political opinions and many of these articles dealt with the issue of social reform. The journal was a great success and quickly became one of the most influential political publications of the 19th century. As well as writing articles for the journal, Brougham wrote the book An Inquiry into the Colonial Policy of the European Powers (1803) where he attacked the slave trade.

Brougham worked as a lawyer in Edinburgh for three years but he came to the conclusion that his radical political views would prevent him from obtaining promotion so in 1804 he decided to move to London, where he became friends with a group of radicals that included Thomas Barnes, William Hazlitt, Leigh Hunt, Lord Byron, and Charles Lamb. Soon after arriving in the capital Brougham published a pamphlet, A Concise Statement of the Question Regarding the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Brougham developed a reputation as a lawyer with progressive views. This brought Brougham to the attention of the leaders of the Whigs and he was given the task of organising the press campaign in the 1807 General Election. Three years later, John Russell, the 6th Duke of Bedford, a Whig aristocrat, offered Brougham, the parliamentary seat of Camelford. The constituency only had twenty votes and they were all under the control of Russell. Although Henry Brougham disapproved of this corrupt system he accepted the seat in order to enter the House of Commons.

Brougham soon established himself as one of the leading radicals in Parliament. His first great parliamentary speech was on the issue of slavery. In June 1810 he complained that the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was ineffective. Brougham argued that Britain was doing nothing to end "this abominable commerce". Yet she was always ready to use her power "when the object is to obtain new colonies and extend the slave trade; then we can both conquer and treat; we have force enough to seize whole provinces where the slave trade might be planted and skill enough to retain them and the additional commerce in slaves their cultivation requires." James Stephen, the MP for Tralee, and one of those who campaigned against the slave trade, replied: "we have at least delivered ourselves as a nation from the guilt and shame of authorising that cruel and opprobrious traffic... If we have effected nothing more I shall rejoice and bless God to the last hour for this happy deliverance."

In March 1811 Brougham introduced a bill (which passed) to make it a felony to trade in slaves. This was a much more effective sanction to the ones that was part of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act. His biographer, Michael Lobban, has pointed out: "Throughout his life Brougham continued to speak out, in parliament and in public, against the evils of the slave trade and slavery, and he remained proud of his own contribution to the cause of the abolitionists."

He was less radical on the subject of parliamentary reform. He attacked the views of Thomas Paine that had been expressed in The Rights of Man. He also disagreed with Francis Burdett and Henry Hunt, the main supporters of adult suffrage in the House of Commons. He agreed with Samuel Romilly who argued that he was "no friend to universal suffrage … or even to annual parliaments... No conduct can, in my eyes, be more criminal than that of availing one's self of the prejudiced clamours of the ignorant or misinformed to accomplish any political purpose, however good or desirable in itself."

John Russell had financial problems and had to sell Camelford in 1812 and Brougham had to find another seat in the next election. John Cartwright offered him the seat in Middlesex but he refused to support universal suffrage and annual parliaments. Instead, Brougham decided to become the Whig parliamentary candidate in Liverpool. This was a brave decision as the city was one of the main centres of the British slave trade. Brougham was defeated by George Canning and was without a seat in the House of Commons for the next four years.

Henry Brougham continued to work as a lawyer and in August 1812 he defended thirty-eight handloom weavers who had been arrested by Joseph Nadin, Deputy Constable of Manchester, while trying to form a trade union. Their leader John Knight was charged with "administering oaths to weavers pledging them to destroy steam looms" and the rest of the men were accused of attending a seditious meeting. As a result of Brougham's brilliant defence, all thirty-eight were acquitted.

In 1815 Earl of Darlington offered Henry Brougham the vacant seat of Winchelsea. Like Camelford, Winchelsea was a pocket borough. Unable to find a seat which he had a chance of winning, Brougham accepted the offer. Samuel Whitbread was dead and Samuel Romilly too ill to attend, Brougham became the Whigs most effective speakers in parliament. He also became more concerned about parliamentary reform telling Francis Place that there was a need to "change the whole of the present ruinous system".

In the House of Commons Brougham became the leading spokesmen for the radicals. In 1819 he blamed the Tory government and Manchester's local magistrates for the Peterloo Massacre. "The magistrates there (in Manchester) and all over Lancashire I have long known for the worst in England, the most bigotted, violent and active. I am quite indignant at this Manchester business, but I fear, with you, that we can do nothing till parliament meets." Brougham also spoke out against the prison sentences imposed on Henry Orator Hunt, John Knight, Samuel Bamford and the other organisers of the meeting at St. Peter's Field.

Michael Lobban has pointed out: "Brougham married on 1 April 1819. Always slightly uncomfortable in the company of women, he had had occasional affairs, as in 1816, when he had a liaison in Geneva with Caroline Lamb, wife of George Lamb. In 1818 he courted (and was rejected by) Georgiana Pigou, and soon afterwards married a widow, Mary Ann Spalding, daughter of Thomas Eden of Wimbledon and niece of Lord Auckland. She brought with her two children, a house in Mayfair, and an annual income of £1500, but little intellectual stimulation. None of Brougham's friends was told of the marriage, which took place at Coldstream, until well after the event. There was some talk that his marriage was the consequence of an indiscretion, and a daughter (who died in infancy) was born in November. Brougham's wife remained a sickly and nervous woman, particularly after the birth of their second daughter, Eleanor Louise, in October 1822. Brougham continued, after his marriage, to have affairs, beginning a liaison with Harriette Wilson, who blackmailed him throughout the late 1820s and early 1830s. He paid up, rather than risk public embarrassment."

Brougham was actively involved in educational reform. He supported the Ragged Schools Union and Mechanics Institutes. In 1826 he joined forces with Charles Knight to establish the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, an organisation that published cheap and accessible works on both scientific and artistic subjects. Brougham's ideas on state-funded education were unpopular and the education bills that he introduced to Parliament in 1820, 1835, 1837, 1838 and 1839 were all defeated.

Brougham continued to campaign against slavery. On 5th March 1828, Brougham argued in the House of Commons: "The progress of the colonies is so slow as to be imperceptible to all human eyes save their own. They are standing still instead of advancing towards the goal at which it was the wish of the House they should gradually but certainly arrive... Out of twenty heads of regulation and improvement recommended to them there was no less than nine in which not a single colony has not taken a single step. In Jamaica and Barbados with populations together of nearly half a million slaves not one step has been taken with respect to sixteen out of twenty heads proposed to them by the Colonial Department." Brougham complained that the Government had lamely replied that it was their desire "to introduce a system which will be beneficial to the slaves without infringing on the rights of private property".

The Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery continued to grow. In May 1830, 2,000 people packed the Freemasons' Hall to hear their leaders denounce the slave system. One member argued: "The friends of humanity have slept too long at their posts while the enemy never slackens his endeavours to perpetuate the present abuse by which his avarice is fostered. Indeed I fear that until some black O'Connell or an African Bolivar devotes his unceasing energy to effecting emancipation of his negro brethren, the condition of the slaves... will never change."

Brougham, who was at the meeting, and had recently been given a peerage and had been appointed Lord Chancellor in Lord Grey's new Whig government, argued that Parliament was not ready to free the slaves in the colonies. Daniel O'Connell, who was also in Freemasons' Hall, challenged Brougham: "Let us make a beginning. Whatever day we propose we will be met with the answer, you are too hasty; you do not give enough time to educate the young descendants of slaves before they come to man's estate, and make them fit for freedom."

During the meeting the meeting the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery agreed to drop the words "gradual abolition" from its title. Sarah Wedgwood suggested a plan for a new campaign to bring about immediate abolition. The following year they presented a petition to the House of Commons calling for the "immediate freeing of newborn children of slaves".

Lord Brougham, who had been arguing for parliamentary reform for over thirty years, played an important role in persuading the House of Lords to pass the 1832 Reform Act. One observer commented: "When the bill returned to the Lords in the new parliament, he delivered a speech lasting over three hours, in temperatures of 85° F, ending in the lord chancellor, by now the worse for drink, on his knees, begging the Lords to pass the bill."

His biographer, Michael Lobban, has described him as: "Tall and thin, with a high forehead, deep-set eyes, and a long, upturned nose, which proved to be the delight of caricaturists, and with a prodigious amount of energy, Brougham was both a congenial and warm-hearted man who could captivate any audience with his wit and learning, and an awkward and abrupt man, who could offend with his eccentric conduct and bore with his vain self-seeking. He aspired to be a polymath who could master science, law, and literature while remaining at the centre of the political stage; but he never stood still long enough to make a permanent impact in any of these fields. As a thinker he cast his net so widely that the vast quantities of print which he produced proved to be of little lasting value."

In 1831 James Cropper and his son-in-law, Joseph Sturge, formed the Young England Abolitionists, a pressure group within the Society for the Abolition of Slavery, that campaigned for a new act of Parliament. It was distinguished from other anti-slavery groups by its unconditional arguments and vigorous campaigning tactics. Peter Archer has argued that they directed "their activities much more in the direction of forming mass opinion."

The Anti-Slavery Society presented a petition to the House of Commons calling for the "immediate freeing of newborn children of slaves". Thomas Clarkson redoubled his efforts and between October 1830 and April 1831, 5,484 petitions calling for an end to slavery was sent to Parliament. However, Clarkson had to wait until 1833 before Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act that gave all slaves in the British Empire their freedom. It contained two controversial features: a transitional apprenticeship period and compensation to owners totalling £20,000,000.

Lord Brougham lost office after the defeat of the Whigs in 1834. Brougham's views were considered to be too radical by Lord Grey's successor, Lord Melbourne, and was not given government office after the Whigs returned to power in April 1835. Lord Brougham remained committed to further political reform and helped Melbourne's government pass the Municipal Reform Bill in 1835.

James Cropper was disappointed by the measure that granted compensation to slave owners and substituting a temporary system of unpaid apprenticeship for slavery. Joseph Sturge visited the West Indies (November 1836 to April 1837) where he collected evidence to demonstrate the flaws in the legislation. On his return he published The West Indies in 1837 and gave evidence for seven days before a committee of the House of Commons. As a result of his campaign in 1838 the apprenticeship system was terminated.

On 29th March, 1838, Lord Brougham, argued in the House of Lords: "compulsory apprenticeship, which was another name for slavery, and could only be justified by expediency, is proved to be inexpedient, and nothing remains but the duty of the mother country to afford all her subjects the protection of equal laws." Jack Gratus, the author of The Great White Lie (1973) has commented: "With these strong words the highest legal authority in the land condemned fifty years of parliamentary inactivity under the guise of ameliorative legislation on behalf of the slaves, and condemned, moreover, the final act of hypocrisy for the fraud it was."

In 1844 he founded the Law Amendment Society. This organisation provided him with material and measures to present before parliament, and kept him in the forefront of law reform. Michael Lobban has pointed out: "For thirty years he proposed reforms ranging from the structure of the court system to real property law and the law of marriage and divorce." A strong supporter of equal rights for women, Brougham played an important role in the passing of the Matrimonial Causes Act in 1857.

Henry Brougham died on 17th May, 1868 at Château Eleanor-Louise, Cannes, and was buried on 24th May in the town's cemetery.

On this day in 1913 the East London Federation of Suffragettes is formed by Sylvia Pankhurst, Keir Hardie, Norah Smyth, Julia Scurr, Mary Phillips, Millie Lansbury, Eveline Haverfield, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Maud Joachim, Nellie Cressall and George Lansbury. An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party. Pankhurst also began production of a weekly paper for working-class women called The Women's Dreadnought.

As June Hannam has pointed out: "The ELF was successful in gaining support from working women and also from dock workers. The ELF organized suffrage demonstrations and its members carried out acts of militancy. Between February 1913 and August 1914 Sylvia was arrested eight times. After the passing of the Prisoners' Temporary Discharge for Ill Health Act of 1913 (known as the Cat and Mouse Act) she was frequently released for short periods to recuperate from hunger striking and was carried on a stretcher by supporters in the East End so that she could attend meetings and processions. When the police came to re-arrest her this usually led to fights with members of the community which encouraged Sylvia to organize a people's army to defend suffragettes and dock workers. She also drew on East End traditions by calling for rent strikes to support the demand for the vote."

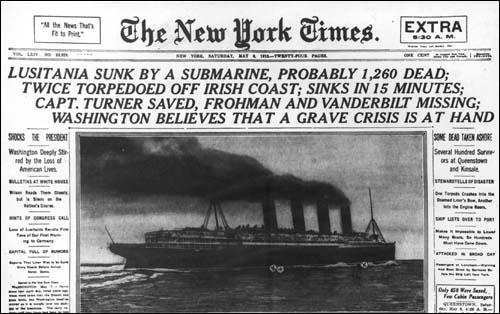

On this day in 1915 the Lusitania was sunk by a German U-Boat. was at 32,000 tons, the largest passenger vessel on transatlantic service, left New York harbour for Liverpool on 1st May, 1915. It was 750ft long, weighed 32,500 tons and was capable of 26 knots. On this journey the ship carried 1,257 passengers and 650 crew.

Most of the passengers were aware of the risks they were taking. Margaret Haig Thomas, was the daughter of David Alfred Thomas, who had been sent by David Lloyd George to the United States to arrange the supply of munitions for the British armed forces. Margaret later recalled that in New York City during the weeks preceding the voyage "there was much gossip of submarines". It was "stated and generally believed that a special effort was to be made to sink the great Cunarder so as to inspire the world with terror". On the morning that the Lusitania set sail the warning that had been issued by the German Embassy on 22nd April 1915, was "printed in the New York morning papers directly under the notice of the sailing of the Lusitania". Margaret commented that "I believe that no British and scarcely any American passengers acted on the warning, but we were most of us very fully conscious of the risk we were running."

At 1.20pm on 7th May 1915, the U-20, only ten miles from the coast of Ireland, surfaced to recharge her batteries. Soon afterwards Captain Schwieger, the commander of the German U-Boat, observed the Lusitania in the distance. Schwieger gave the order to advance on the liner. The U20 had been at sea for seven days and had already sunk two liners and only had two torpedoes left. He fired the first one from a distance of 700 metres. Watching through his periscope it soon became clear that the Lusitania was going down and so he decided against using his second torpedo.

William McMillan Adams was travelling with his father. "I was in the lounge on A Deck when suddenly the ship shook from stem to stem, and immediately started to list to starboard. I rushed out into the companionway. While standing there, a second, and much greater explosion occurred. At first I thought the mast had fallen down. This was followed by the falling on the deck of the water spout that had been made by the impact of the torpedo with the ship. My father came up and took me by the arm. We went to the port side and started to help in the launching of the lifeboats."

Adams soon discovered that there was a major problem with the lifeboats: "Owing to the list of the ship, the lifeboats had a tendency to swing inwards across the deck and before they could be launched, it was necessary to push them over the side of the ship... It was impossible to lower the lifeboats safely at the speed at which the Lusitania was still going. I saw only two boats launched from this side. The first boat to be launched, for the most part full of women, fell sixty or seventy feet into the water, all the occupants being drowned. This was owing to the fact that the crew could not work the davits and falls properly, so let them slip out of their hands, and sent the lifeboats to destruction."

Margaret Haig Thomas was also unable to get into a lifeboat: "It became impossible to lower any more from our side owing to the list on the ship. No one else except that white-faced stream seemed to lose control. A number of people were moving about the deck, gently and vaguely. They reminded one of a swarm of bees who do not know where the queen has gone. I unhooked my skirt so that it should come straight off and not impede me in the water. The list on the ship soon got worse again, and, indeed, became very bad. Presently the doctor said he thought we had better jump into the sea. I followed him, feeling frightened at the idea of jumping so far (it was, I believe, some sixty feet normally from A deck to the sea), and telling myself how ridiculous I was to have physical fear of the jump when we stood in such grave danger as we did. I think others must have had the same fear, for a little crowd stood hesitating on the brink and kept me back. And then, suddenly, I saw that the water had come over on to the deck. We were not, as I had thought, sixty feet above the sea; we were already under the sea. I saw the water green just about up to my knees. I do not remember its coming up further; that must all have happened in a second. The ship sank and I was sucked right down with her."

Of the 2,000 passengers on board, 1,198 were drowned, among them 128 Americans. The German newspaper Die Kölnische Volkszeitung supported the decision to sink the Lusitania: "The sinking of the giant English steamship in a success of moral significance which is still greater than material success. With joyful pride we contemplate this latest deed of our Navy. It will not be the last. The English wish to abandon the German people to death by starvation. We are more humane. we simply sank an English ship with passengers, who, at their own risk and responsibility, entered the zone of operations."

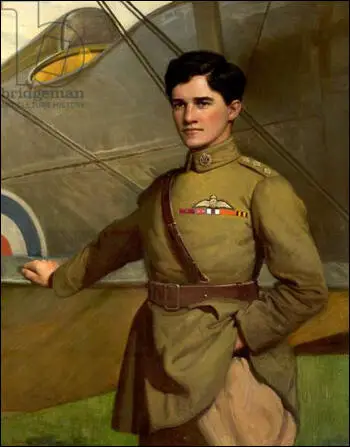

On this day in 1917 English fighter pilot Albert Ball is killed. Ball was born in Nottingham on 14th August 1896. An engineering student when the First World War started, he joined the Sherwood Foresters before transferring to the Royal Flying Corps in 1915. Considered an only average pilot, he began his fighting career in May 1916. At first he concentrated on ambushing poorly defended two-seater German planes.

With his confidence growing, Ball began to make single-handed attacks on German planes flying in formation. His preferred position was a few yards directly beneath his opponent who he would shoot by tilting up his single wing-mounted Lewis gun. Flying a Nieuport 17, Ball supported the offensive at the Somme. By the time he was sent back to England in October 1916, Ball was credited with thirty victories.

Appointed flight commander in No. 56 Squadron, Ball began flying the recently developed S.E.5. On the morning of 6th May 1917, Ball brought down a Albatros D-II. Later that evening he was seen in combat with a German single-seater. The pair crashed in deep cloud and Ball's body was later found in the wreckage. By the time of his death, Ball, who was only twenty years old, had won the Victoria Cross, the Military Cross and the Croix de Guerre.

On this day in 1918 Sir Frederick Maurice wrote a letter to the press stating that ministerial statements were false. The letter appeared on the following morning in the The Morning Post, The Times, The Daily Chronicle and The Daily News. The letter accused David Lloyd George of giving the House of Commons inaccurate information. The letter created a sensation. Maurice was immediately suspended from duty and supporters of Herbert Henry Asquith called for a debate on the issue.

On 9th April, 1918, Lloyd George had told the House of Commons that despite heavy casualties in 1917, the British Army in France was considerably stronger than it had been on January 1917. He also gave details of the number of British troops in Mesopotamia, Egypt and Palestine. Maurice, whose job it was to keep accurate statistics of British military strength, knew that Lloyd George had been guilty of misleading Parliament about the number of men in the British Army. Maurice believed that Lloyd George was deliberately holding back men from the Western Front in an attempt to undermine the position of Sir Douglas Haig.

Maurice wrote to Henry Wilson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff pointing out these inaccuracies. He did not receive a reply and after consulting with his wife and mother, he took the decision to write a letter to the newspapers giving the true figures. Maurice knew that by taking this decision, his military career would be brought to an end. However, as he said in a letter to his daughter Nancy: "I am persuaded that I am doing what is right, and once that is so, nothing else matters to a man. That is I believe Christ meant when he told us to forsake father and mother and children for his sake."

Maurice's biographer, Trevor Wilson: "Despite containing some errors of detail, the charges contained in Maurice's letter were well founded. Haig had certainly been obliged against his wishes to take over from the French the area of front where his army suffered setback on 21 March. The numbers of infantrymen available to Haig were fewer, not greater, than a year before. And there were several more ‘white’ divisions stationed in Egypt and Palestine at the time of the German offensive than the government had claimed."

The debate took place on 9th May and the motion put forward amounted to a vote of censure. If the government lost the vote, David Lloyd George would have been forced to resign. As A.J.P. Taylor has pointed out: "Lloyd George developed an unexpectedly good case. With miraculous sleight of hand, he showed that the figures of manpower which Maurice impuhned, had been supplied from the war office by Maurice's department." Although many MPs suspected that Lloyd George had mislead Parliament, there was no desire to lose his dynamic leadership during this crucial stage of the war. The government won the vote with a clear majority.

Maurice, by writing the letter, had committed a grave breach of discipline. He was retired from the British Army and was refused a court martial or inquiry where he would have been able to show that David Lloyd George had mislead the House of Commons on both the 9th April and 7th May, 1918.

On this day in 1940 George Lansbury died. Lansbury spent the last few years of his life trying to prevent a Second World War. He travelling throughout Europe meeting the political leaders of the various countries. After having talks with Adolf Hitler he believed it was still possible to reach an agreement that would avoid a war. His efforts ended in failure and he died a disillusioned man.

George Lansbury, the son of a railway contractor, was born in Halesworth, Suffolk, on 21st February, 1859. When George was nine years old the family moved to East End. George started work in an office at the age of eleven but after a year he returned to school where he stayed until he was fourteen. This was followed by a succession of jobs as a clerk, a wholesale grocer and working in a coffee bar.

Lansbury later recalled in The Miracle of Fleet Street (1925): "my own first connection with journalism took place... some time between 1874 and 1880, when, as a member of the Whitechapel Church Young Men's Association, I wrote essays for a manuscript journal produced by a group of youngsters whose ages ranged from 16 to 18 years."

Lansbury then started up his own business as a contractor working for the Great Eastern Railway. This was not a success and now married with three children, Lansbury decided in 1884 to emigrate to Australia. The Lansbury family found it difficult to settle in Australia and the following year returned to England and he began work at his father-in-law's timber merchants.

Lansbury was angry about his time in Australia and believed that he had been a victim of untrue propaganda about the country. He came to the conclusion that the emigration authorities were disseminating false information in an effort to entice immigrants to Australia. He joined the campaign against this policy and in doing so obtained his first experience of politics.

In the 1886 General Election Lansbury joined the local Liberal Party. Later that year he was elected General Secretary of the Bow & Bromley Liberal Association. However, Lansbury became disillusioned with the leadership's views on industrial issues and eventually left the party over its unwillingness to support legislation for a shorter working week.

Lansbury joined the Gasworkers & General Labourers Union and in 1889 joined a local strike committee during the London Dockers' Strike of that year. These activities brought him into contact with H.M. Hyndman, the leader of the Social Democratic Federation. Although the two men disagreed with each other over many issues, Lansbury decided to join the party and in 1892 established a branch of the Social Democratic Federation in Bow. This marked the start of Lansbury's long campaign against poverty and unemployment in London.

As a young man, Lansbury had been an atheist. However in the 1890s he was influenced by the religious ideas of people like Stuart Headlam and Philip Snowdon. Lansbury became a Christian Socialist and was later to play an important role in converting people such as James Keir Hardie to Christianity.

In 1892 Lansbury was elected to the Board of Guardians that ran the Poplar Workhouse. Lansbury and his colleagues decided to use their power to change the system. Lansbury, unlike most Guardians, did not believe that the generous treatment of paupers would encourage more people to seek refuge in the workhouse. Over the next few years the Guardians dramatically improved the conditions in their workhouse. With the help of Joseph Fels, they also established a Laindon Farm Colony in the Essex countryside where they provided work for the unemployed and taught them the basics of market gardening.

Lansbury continued to be a member of the Social Democratic Federation and in 1895 he became the party's candidate in a parliamentary election in Walworth. He only obtained 204 votes in that election but in 1900 he obtained 2,558 against the Conservative Party candidate who won with 4,403 votes.

Lansbury found his relationship with H.M. Hyndman, increasing difficult. Lansbury disliked Hyndman's dictatorial method of running the party, he also disagreed with his Marxist views. Lansbury's socialism had been inspired by the teachings of Jesus Christ, whereas Hyndman was a devout follower of Karl Marx, an atheist. In 1903 Lansbury left the Social Democratic Federation and joined the Independent Labour Party, an organisation that contained a large number of Christian Socialists. Three years later the Independent Labour Party became the Labour Party, an organisation led by James Keir Hardie, a man who was converted to Christianity in 1897.

In 1906 the government ordered an inquiry into the running of the Poplar Workhouse. The Board of Guardians were accused of wasting the ratepayers' money by their generous treatment of paupers and the funding of the Laindon Farm Colony. Lansbury, who had been joined as a Guardian by John Burns, another leading figure in the Christian Socialist movement, argued the case for treating people in workhouses with dignity. Although the government report was critical of the Guardians, they refused to change their policy and eventually the authorities decided not to take action against them.

Lansbury was now one of the leading figures in the Labour Party and in the 1910 General Election was elected as the MP for Bow & Bromley. He later wrote: "I had previously fought many elections, but failed to secure the magic letters M.P. until reaching the age of 52. My life since a boy has been a strenuous one, always working from early morning till late at night. Earning my living took tip only a small part of my time. I can truthfully say most of my days have been spent trying to help forward the cause of the common people, to whom I am proud to belong."

Lansbury, along with Keir Hardie, led the campaign in Parliament for votes for women. Lansbury was especially critical of the Cat and Mouse Act and was ordered to leave the House of Commons after shaking his fist in the face of Herbert Asquith, the Prime Minister, and told him that he was "beneath contempt" because of his treatment of WSPU prisoners.

Hardie and Lansbury had trouble persuading all Labour MPs to support votes for women. Many of them argued that the party should make sure all working class men had the vote before it concerned itself with the franchise for women. Others argued that a policy that advocated votes for women was unpopular with the electorate and would result in the Labour Party losing seats in the next General Election.

In October, 1912, George Lansbury decided to draw attention to the plight of WSPU prisoners by resigning his seat in the House of Commons and fighting a by-election in favour of votes for women. Lansbury discovered that a large number of males were still opposed to equal rights for women and he was defeated by 731 votes. The following year he was imprisoned for making speeches in favour of suffragettes who were involved in illegal activities. While in Pentonville he went on hunger strike and was eventually released under the Cat and Mouse Act.

For the next ten years Lansbury was out of the House of Commons and concentrated on journalism. In 1911 he helped start the Daily Herald and two years later became the editor of the newspaper, where he worked closely with the cartoonist Will Dyson and the writers, Henry Brailsford, William Mellor, Norman Angell, George Douglas Cole, John Scurr, Gerald Gould, Morgan Phillips Price, Henry Nevinson, Evelyn Sharp, G. K. Chesterton and Hillaire Belloc. The Countess Muriel de la Warr was the main source of funds for the newspaper. According to Lansbury she "has always been one of the first and most generous of our friends; there has never been a crisis overcome without her help."

Lansbury and his newspaper, the Daily Herald, was opposed to Britain involvement in the First World War. This made him unpopular during the nationalist fervour that developed between 1914 and 1918. In the 1918 General Election, Lansbury, like other anti-war Labour Party candidates was defeated.

In the 1922 General Election Lansbury was elected as the Labour MP for Bow & Bromley with a majority of 7,000. Lansbury was unhappy with the way the Daily Herald became more conservative in its reporting after being taken over by the Labour Party and the TUC after 1923.

Lansbury was also a member of the Poplar Council. The Labour Party had won 39 of the 42 council seats in November 1919. In 1921 Poplar had a rateable value of £4m and 86,500 unemployed to support. Whereas other more prosperous councils could call on a rateable value of £15 to support only 4,800 jobless. George Lansbury, the new mayor of Poplar, proposed that the Council stop collecting the rates for outside, cross-London bodies. This was agreed and on 31st March 1921, Poplar Council set a rate of 4s 4d instead of 6s 10d. On 29th the Councillors were summoned to Court. They were told that they had to pay the rates or go to prison. At one meeting Millie Lansbury said: "I wish the Government joy in its efforts to get this money from the people of Poplar. Poplar will pay its share of London's rates when Westminster, Kensington, and the City do the same."

On 28th August over 4,000 people held a demonstration at Tower Hill. The banner at the front of the march declared that "Popular Borough Councillors are still determined to go to prison to secure equalisation of rates for the poor Boroughs." The Councillors were arrested on 1st September. Five women Councillors, including Julia Scurr, Millie Lansbury and Susan Lawrence, were sent to Holloway Prison. Twenty-five men, including George Lansbury and John Scurr, went to Brixton Prison. On 21st September, public pressure led the government to release Nellie Cressall, who was six months pregnant. Julia Scurr reported that the "food was unfit for any human being... fish was given on Friday, they told us, that it was uneatable, in fact, it was in an advanced state of decomposition".

Instead of acting as a deterrent to other minded councils, several Metropolitan Borough Councils announced their attention to follow Poplar's example. The government led by Stanley Baldwin and the London County Council were now put in a difficult position. Harry Gosling volunteered to negotiate a settlement. As he later recalled: "The actual drafting of the document was no easy matter with such critics as George Lansbury and his son Edgar, Susan Lawrence, John Scurr, and all the others round the table, ready to object at any chance word and upset the whole thing in their eagerness to uphold their cause. Every one of these men and women stood for what was in their view a great principle, and yet a formula had to be found to enable the judges to release them."

On 12th October, the Councillors were set free. The Councillors issued a statement that said: "We leave prison as free men and women, pledged only to attend a conference with all parties concerned in the dispute with us about rates... We feel our imprisonment has been well worth while, and none of us would have done otherwise than we did. We have forced public attention on the question of London rates, and have materially assisted in forcing the Government to call Parliament to deal with unemployment."

While in Holloway Prison, Lansbury's daughter-in-law, Millie Lansbury developed pneumonia and she died on 1st January 1922. According to Janine Booth she had told friends " that imprisonment had weakened her physically, leaving her body unable to fight off the illness that killed her." Lansbury said: "Minnie, in her 32 years, crammed double that number of years' work compared with what many of us are able to accomplish. Her glory lies in the fact that with all her gifts and talents one thought dominated her whole being night and day: How shall we help the poor, the weak, the fallen, weary and heavy-laden, to help themselves? When, a soldier like Minnie passes on, it only means their presence is withdrawn, their life and work remaining an inspiration and a call to us each to close the ranks and continue our march breast forward."

In the 1923 General Election, George Lansbury, John Scurr and Susan Lawrence were all elected to the House of Commons. The Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions".

On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. MacDonald had not been fully supportive of the Poplar Councillors since he thought that "public doles, Popularism, strikes for increased wages, limitation of output, not only are not Socialism but may mislead the spirit and policy of the Socialist movement." George Lansbury was therefore not offered a post in his Cabinet.

John Wheatley, the new Minister of Health, had been a supporter of the Poplar Councillors. Edgar Lansbury wrote in The New Leader that he was sure that Wheatley would "understand and sympathise with them in this horrible problem of poverty, misery and distress which faces them." Lansbury's assessment was correct and as Janine Booth, the author of Guilty and Proud of It! Poplar's Rebel Councillors and Guardians 1919-25 (2009), has pointed out: "Wheatley agreed to rescind the Poplar order. It was a massive victory for Poplar, whose guardians had lived with the threat of legal action for two years and were finally vindicated." A. J. P. Taylor has argued that at this time Lansbury was "the most beloved figure in modern British politics."

In 1925 Lansbury started the Lansbury's Labour Weekly. The newspaper rapidly reached a circulation of 172,000 and provided an important source of news during the 1926 General Strike. Although his left-wing ideas made him unpopular with some of the leaders of the Labour Party, Lansbury was elected Chairman party in 1928. The following year he became Commissioner for Works in the Labour government led by Ramsay MacDonald.

The election of the Labour Government coincided with an economic depression and Ramsay MacDonald was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. In January 1929, 1,433,000 people were out of work, a year later it reached 1,533,000. By March 1930, the figure was 1,731,000. In June it reached 1,946,000 and by the end of the year it reached a staggering 2,725,000. That month MacDonald invited a group of economists, including John Maynard Keynes, J. A. Hobson, George Douglas Cole and Walter Layton, to discuss this problem. However, he rejected all those ideas that involved an increase in public spending.

In March 1931 Ramsay MacDonald asked Sir George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problems. The committee included two members that had been nominated from the three main political parties. At the same time, John Maynard Keynes, the chairman of the Economic Advisory Council, published his report on the causes and remedies for the depression. This included an increase in public spending and by curtailing British investment overseas.

Philip Snowden rejected these ideas and this was followed by the resignation of Charles Trevelyan, the Minister of Education. "For some time I have realised that I am very much out of sympathy with the general method of Government policy. In the present disastrous condition of trade it seems to me that the crisis requires big Socialist measures. We ought to be demonstrating to the country the alternatives to economy and protection. Our value as a Government today should be to make people realise that Socialism is that alternative."

When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it forecast a huge budget deficit of £120 million and recommended that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. The two Labour Party nominees on the committee, Arthur Pugh and Charles Latham, refused to endorse the report.

The cabinet decided to form a committee consisting of Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Arthur Henderson, Jimmy Thomas and William Graham to consider the report. On 5th August, John Maynard Keynes wrote to MacDonald, describing the May Report as "the most foolish document I ever had the misfortune to read." He argued that the committee's recommendations clearly represented "an effort to make the existing deflation effective by bringing incomes down to the level of prices" and if adopted in isolation, they would result in "a most gross perversion of social justice". Keynes suggested that the best way to deal with the crisis was to leave the Gold Standard and devalue sterling. Two days later, Sir Ernest Harvey, the deputy governor of the Bank of England, wrote to Snowden to say that in the last four weeks the Bank had lost more than £60 million in gold and foreign exchange, in defending sterling. He added that there was almost no foreign exchange left.

Philip Snowden presented his recommendations to the MacDonald Committee that included the plan to raise approximately £90 million from increased taxation and to cut expenditure by £99 million. £67 million was to come from unemployment insurance, £12 million from education and the rest from the armed services, roads and a variety of smaller programmes. Arthur Henderson and William Graham rejected the idea of the proposed cut in unemployment benefit and the meeting ended without any decisions being made.

Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Susan Lawrence both decided to resign from the government if the cuts to the unemployment benefit went ahead: Pethick-Lawrence wrote: "Susan Lawrence came to see me. As Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health, she was concerned with the proposed cuts in unemployment relief, which she regarded as dreadful. We discussed the whole situation and agreed that, if the Cabinet decided to accept the cuts in their entirety, we would both resign from the Government."

Ramsay MacDonald went to see George V about the economic crisis on 23rd August. He warned the King that several Cabinet ministers were likely to resign if he tried to cut unemployment benefit. MacDonald wrote in his diary: "King most friendly and expressed thanks and confidence. I then reported situation and at end I told him that after tonight I might be of no further use, and should resign with the whole Cabinet.... He said that he believed I was the only person who could carry the country through."

According to Harold Nicolson, the King decided to consult the leaders of the Conservative and Liberal Parties. Herbert Samuel told the King that he should try and persuade MacDonald to make the necessary economies. Stanley Baldwin agreed and said he was willing to serve under MacDonald in a National Government.

After another Cabinet meeting where no agreement about how to deal with the economic crisis could be achieved, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to resign. Sir Clive Wigram, the King's private secretary, later recalled that George V "impressed upon the Prime Minister that he was the only man to lead the country through the crisis and hoped that he would reconsider the situation." At a meeting with Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain and Herbert Samuel MacDonald told them that if he joined a National Government it "meant his death warrant". According to Chamberlain he said "he would be a ridiculous figure unable to command support and would bring odium on us as well as himself."

On 24th August 1931 Ramsay MacDonald returned to the palace and told the King that he had the Cabinet's resignation in his pocket. The King replied that he hoped that MacDonald "would help in the formation of a National Government." He added that by "remaining at his post, his position and reputation would be much more enhanced than if he surrendered the Government of the country at such a crisis." Eventually, he agreed to form a National Government.

The Labour Party was appalled by what they considered to be MacDonald's act of treachery. Arthur Henderson commented that MacDonald had never looked into the faces of those who had made it possible for him to be Prime Minister.

On 8th September 1931, the National Government's programme of £70 million economy programme was debated in the House of Commons. This included a £13 million cut in unemployment benefit. Tom Johnson, who wound up the debate for the Labour Party, declared that these policies were "not of a National Government but of a Wall Street Government". In the end the Government won by 309 votes to 249, but only 12 Labour M.P.s voted for the measures.

On 26th September, the Labour Party National Executive decided to expel all members of the National Government including Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey. As David Marquand has pointed out: "In the circumstances, its decision was understandable, perhaps inevitable. The Labour movement had been built on the trade-union ethic of loyalty to majority decisions. MacDonald had defied that ethic; to many Labour activists, he was now a kind of political blackleg, who deserved to be treated accordingly."

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Lansbury won his seat for Bow & Bromley and became the leader of the Labour opposition.

Ben Pimlott has argued in Labour and the Left (1977): "Lansbury's politics, rooted in bitter experience of unemployment and hardship as an emigrant in Australia in the 1880s, and belonging to the oldest traditions of Christian Socialism and street corner demogoguery, were in some ways suited to the beleaguered opposition of 1931. One reaction to the crisis and defeat was an eagerness to return to fundamental principles: Lansbury reflected this mood."

George Lansbury hated fascism but as a pacifist he was opposed to using violence against it. When Italy invaded Abyssinia he refused to support the view that the League of Nations should use military force against Mussolini's army. After being criticised by several leading members of the Labour Party, Lansbury resigned as leader of the party.

On this day in 1940 a Conservative Party MP and former cabinet minister, Leo Amery, called on Neville Chamberlain to resign as prime minister. .

The Prime Minister gave us a reasoned, argumentative case for our failure. It is always possible to do that after every failure. Making a case and winning a war are not the same thing. Wars are won, not by explanation after the event, but by foresight, by clear decision and by swift action. I confess that I did not feel there was one sentence in the Prime Minister's speech this afternoon which suggested that the Government either foresaw what Germany meant to do, or came to a clear decision when it knew what Germany had done, or acted swiftly or consistently throughout the whole of this lamentable affair.

The Prime Minister, both the other day and today, expressed himself as satisfied that the balance of advantage lay on our side. He laid great stress on the heaviness of the German losses and the lightness of ours. What did the Germans lose? A few thousand men, nothing to them, a score of transports, and part of a Navy which anyhow cannot match ours. What did they gain? They gained Norway, with the strategical advantages which, in their opinion at least, outweigh the whole of their naval losses. They have gained the whole of Scandinavia. What have we lost? To begin with, we have lost most of the Norwegian Army, not only such as it was but such as it might have become, if only we had been given time to rally and re-equip it.

We must have, first of all, a right organization of government. What is no less important today is that the Government shall be able to draw upon the whole abilities of the nation. It must represent all the elements of real political power in this country, whether in this House or not. The time has come when hon. and right hon. Members opposite must definitely take their share of the responsibility. The time has come when the organization, the power and influence of the Trades Union Congress cannot be left outside. It must, through one of its recognized leaders, reinforce the strength of the national effort from inside. The time has come, in other words, for a real National Government. I may be asked what is my alternative Government. That is not my concern: it is not the concern of this House. The duty of this House, and the duty that it ought to exercise, is to show unmistakably what kind of Government it wants in order to win the war. It must always be left to some individual leader, working perhaps with a few others, to express that will by selecting his colleagues so as to form a Government which will correspond to the will of the House and enjoy its confidence. So I refuse, and I hope the House will refuse, to be drawn into a discussion on personalities.

What I would say, however, is this: Just as our peace-time system is unsuitable for war conditions, so does it tend to breed peacetime statesmen who are not too well fitted for the conduct of war. Facility in debate, ability to state a case, caution in advancing an unpopular view, compromise and procrastination are the natural qualities - I might almost say, virtues - of a political leader in time of peace. They are fatal qualities in war. Vision, daring, swiftness and consistency of decision are the very essence of victory. In our normal politics, it is true, the conflict of party did encourage a certain combative spirit. In the last war we Tories found that the most perniciously aggressive of our opponents, the right hon. Member for Carnarvon Boroughs, was not only aggressive in words, but was a man of action. In recent years the normal weakness of our political life has been accentuated by a coalition based upon no clear political principles. It was in fact begotten of a false alarm as to the disastrous results of going off the Gold Standard. It is a coalition which has been living ever since in a twilight atmosphere between Protection and Free Trade and between unprepared collective security and unprepared isolation. Surely, for the Government of the last ten years to have bred a band of warrior statesmen would have been little short of a miracle. We have waited for eight months, and the miracle has not come to pass. Can we afford to wait any longer?

Somehow or other we must get into the Government men who can match our enemies in fighting spirit, in daring, in resolution and in thirst for victory. Some 300 years ago, when this House found that its troops were being beaten again and again by the dash and daring of the Cavaliers, by Prince Rupert's Cavalry, Oliver Cromwell spoke to John Hampden. In one of his speeches he recounted what he said. It was this:

'I said to him, "Your troops are most of them old, decayed serving men and tapsters and such kind of fellows." You must get men of a spirit that are likely to go as far as they will go, or you will be beaten still.'

It may not be easy to find these men. They can be found only by trial and by ruthlessly discarding all who fail and have their failings discovered. We are fighting today for our life, for our liberty, for our all; we cannot go on being led as we are.

I have quoted certain words of Oliver Cromwell. I will quote certain other words. I do it with great reluctance, because I am speaking of those who are old friends and associates of mine, but they are words which, I think, are applicable to the present situation. This is what Cromwell said to the Long Parliament when he thought it was no longer fit to conduct the affairs of the nation:

"You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go".

On this day in 1953 film director Robert Rossen names fifty-seven former members of the Communist Party. After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. Rossen was one of those named as a former member of the Communist Party. He appeared before the HUAC on 25th January, 1951, but like the Hollywood Ten, refused to name other party members.

Rossen was blacklisted and was unable to find work over the next two years. Rossen was offered a deal and on 7th May, 1953, he appeared again in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee. This time Rossen gave the HUAC the names of fifty-seven members of the Communist Party.

After his testimony Rossen was free to pursue his career in Hollywood. This included the films Mambo (1954), Alexander the Great (1956), Island in the Sun (1956), They Came to Cordura (1959), The Hustler (1961) and Lilith (1964).