On this day on 6th March

On this day in 1831 Philip Sheridan was born in Albany, New York. He studied at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point but was involved in a serious breach of discipline after attacking another soldier with a bayonet. He graduated in 1853 and after joining the United States Army spent most of the next nine years defending frontier posts.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War Sheridan was given an administrative post in St. Louis. Accused of corruption, Sheridan was saved from being court-martialed by General Henry Halleck who appointed him colonel of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry. In July he led a highly successful attack on the Confederate Army at Booneville, Mississippi.

As a result of this action Sheridan was made a brigadier general. He served with distinction at Perryville (October, 1862) and Stones River (December, 1862) and Chickamauga (September, 1863).

In March, 1864, Ulysses S. Grant was named lieutenant general and the commander of the Union Army. He joined the Army of the Potomac and appointed Sheridan as head of the Cavalry Corps. They crossed the Rapidan and entered the Wilderness. When Robert E. Lee heard the news he sent in his troops, hoping that the Union's superior artillery and cavalry would be offset by the heavy underbrush of the Wilderness. Fighting began on the 5th May and two days later smoldering paper cartridges set fire to dry leaves and around 200 wounded men were either suffocated or burned to death. Of the 88,892 men that Grant took into the Wilderness, 14,283 were casualties and 3,383 were reported missing. Lee lost 7,750 men during the fighting.

After the battle Ulysses S. Grant moved south and on May 26th sent Sheridan and his cavalry ahead to capture Cold Harbor from the Confederate Army. Lee was forced to abandon Cold Harbor and his whole army well dug in by the time the rest of the Union Army arrived. Grant's ordered a direct assault but afterwards admitted this was a mistake losing 12,000 men "without benefit to compensate".

In May 1864 Sheridan led the attacks on Richmond. During one of these battles at Yellow Tavern, his legendary opponent, Jeb Stuart was killed. Ulysses S. Grant rated Sheridan very highly and in August , 1864 he gave him the command of the Shenandoah Valley campaign. Sheridan and 40,000 soldiers entered the valley and soon encountered troops led by Jubal Early who had just returned from Washington. After a series of minor defeats Sheridan eventually gained the upper hand. His men now burnt and destroyed anything of value in the area and after defeating Early in another large-scale battle on 19th October, the Union Army took control of the Shenandoah Valley.

On 1st April Sheridan attacked at Five Forks. The Confederates, led by Major General George Pickett, were overwhelmed and lost 5,200 men. On hearing the news, Robert E. Lee decided to abandon Richmond and President Jefferson Davis, his family and government officials, was forced to flee from the city.

After the war Philip Sheridan was military governor of Louisiana and Texas, but his Reconstruction measures made him unpopular with President Andrew Johnson and he was removed from office. He remained in the United States Army and in 1884 he succeeded William T. Sherman as commander in chief. His autobiography, Personal Memoirs was published in the year of his death.

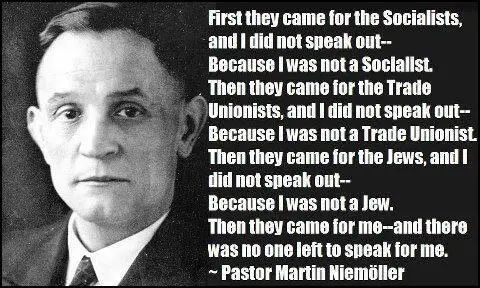

On this day in 1834 George du Maurier was born in Paris. He studied art in France and Germany before moving to London where he established himself as an illustrator. His work appeared in the Cornhill Magazine and the Illustrated Times.

In 1864 he joined the staff of Punch, where he became known as a gentle satirist of middle and upper-class society. He also wrote and illustrated three novels, Peter Ibbetson (1891), the best-selling, Trilby (1894) and The Martian (1897). George du Maurier died on 8th October 1896.

On this day in 1836 Davy Crockett dies at the Battle of the Alamo. David Crockett was born in Hawkins County, Tennessee, on 17th August, 1786. His father, John Crockett, moved his family to Jefferson County in 1794 where he established a log-cabin tavern on the Knoxville-Abingdon Road.

Crockett ran away from home at 12 to escape being punished by his father. He lived for a time in Baltimore before moving to Alabama. He married Mary Finley in August, 1806, and settled in Lincoln County, Tennessee. Later he served under Andrew Johnson as a scout in the Creek War (1813-14).

In 1821 he was elected colonel of the militia and later became a bear hunter in Tennessee. He also became involved in transporting lumber to New Orleans. Crockett took a keen interest in politics and after a period in the Tennessee legislature (1821-24) was elected to Congress in 1827. Crockett openly opposed the land policies of President Andrew Johnson and as a result was defeated by William Fitzgerald in the 1831 election.

Crockett became a national figure in the United States when The Life and Adventures of Colonel David Crockett of West Tennessee was published. This publicity helped him return to Congress in 1833. The following year he published his autobiography, A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee. However, this failed to help his political career and he was defeated in the 1835 congressional elections.

Disillusioned by this political reverse, Crockett decided to move to Texas and arrived in February, 1836. He became involved in the Texas Revolution and joined the Texas volunteers based at San Antonio de Bexar. General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna and 7,000 Mexican troops arrived in San Antonio on 23rd February, 1836. About 200 Texans took refuge in the fortified grounds of the Alamo.

Samuel Houston signed the declaration of Texas independence on 2nd March, 1836. General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna now became determined to take the Alamo. He ordered the shelling of the fortress but the Texans refused to surrender. On 6th March the Mexican army stormed the fortress. During the battle 189 Texans were killed. This included Davy Crockett, James Bowie and William Travis.

On this day in 1888 Louisa Alcott died. Louisa Alcott was born in Germantown, Pennsylvania, on 29th November, 1832. Alcott was educated by her father, Bronson Alcott, the head of Temple School in Boston. As a young woman she was befriended by Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, she wrote her first book, Flower Fables, when she was only sixteen.

During the American Civil War Alcott worked as a nurse in a Union Army hospital (1861-63). However, after contracting typhoid in 1863 she was sent home. She documented her war experiences in her book Hospital Sketches (1863). Alcott also had some of her short stories published in Atlantic Monthly.

Alcott achieved literary success with the publication of her autobiographical novel Little Women (1868) and its sequel, Good Wives (1869). Other novels aimed at the youth market included An Old Fashioned Girl (1870), Little Men (1871), Eight Cousins (1876) and Rose in Bloom (1876). Alcott later described these books as "moral pap for the young". Alcott also wrote two feminist novels, Work, A Study of Experience (1873), and A Modern Mephistopheles (1877). Louisa Alcott died in Boston on 6th March, 1888.

On this day in 1893 John Bernard was born in Corsica, France, on 6th March, 1893. In 1907 the family emigrated to the United States and settled in Eveleth, Minnesota.

After being educated at the local public school, Bernard became an iron-ore miner (1910 to 1917). During the First World War Barnard served in the United States Army and reached the rank of corporal. On his return to America he worked as a fireman (1920-36).

A member of the Farmer-Labor Party, Bernard was elected to the 75th Congress (3rd January, 1937 - 3rd January, 1939). Bernard and Jerry O'Connell were the only Congressmen to visit the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War.

Bernard failed to be elected for the 76th Congress. For the rest of his life he was a labour organizer and civil rights activist. John Bernard died at Long Beach, California, on 6th August, 1983.

On this day in 1930 Herbert Gladstone, the fourth son of William Gladstone, was born in 1854. After being educated at Eton and University College, Oxford, Gladstone became a history lecturer at Oxford University.

In the 1880 General Election Gladstone was elected as Liberal MP for Leeds. In the House of Commons Gladstone, a member of the Temperance Society, advocated reform of the alcohol trade and the abolition of the powers of the House of Lords.

After entering the House of Commons Gladstone worked as his father's unpaid Parliamentary Secretary. The following year William Gladstone appointed his son as Lord of the Treasury (1881-85). This was followed by periods as Deputy Commissioner of Works (1885-86), Financial Secretary at the War Office (1886), Under Secretary to the Home Office (1892-94), Commissioner of Works (1894-95) and Chief Whip (1899-1905).

In the government formed by Herbert Asquith following the 1910 General Election, Gladstone became Home Secretary. Created Viscount Gladstone in December, 1910, he became an important figure in the struggle with the House of Lords over its reluctance to pass the legislation of the Liberal government.

During he First World War Gladstone served as Governor-General of South Africa and head of the War Refugees Association.

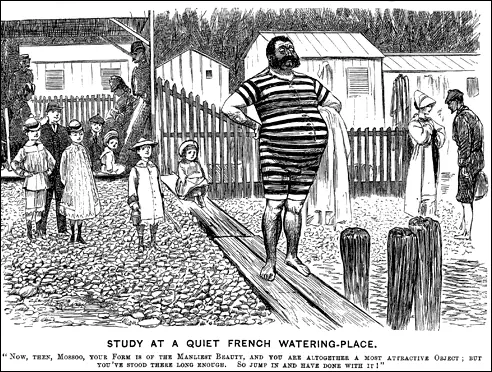

On this day in 1933 President Franklin D. Roosevelt closes all U.S. banks and freezes all financial transactions. The economic depression in the early 1930s had a disastrous impact on the banking system in America. Private banks which had invested in stocks and shares found that the Wall Street Crash had severely reduced their funds.

In December, 1930, the Bank of the United States, with more than 410 branches in California and more than a million depositors, was forced to close. According to David M. Kennedy the closing of this one bank another "two hundred smaller banks closed because of the deposits in that bank from the others."

President Roosevelt took office on 4th March, 1933. His first act as president was to deal with the country's banking crisis. Since the beginning of the depression, a fifth of all banks had been forced to close. Already 389 banks had shut their doors since the beginning of the year. As a consequence, around 15% of people's life-savings had been lost. Banking was at the point of collapse. In 47 of the 48 states banks were either closed or working under tight restrictions. To buy time to seek a solution Roosevelt declared a four-day bank holiday. It has been claimed that the term "bank holiday" was used to seem festive and liberating. "The real point - the account holders could not use their money or get credit - was obscured."

Roosevelt's advisers, Louis Brandeis, Felix Frankfurter, and Rexford G. Tugwell agreed with progressives who wanted to use this opportunity to establish a truly national banking system. Heads of great financial institutions opposed this idea. Louis Howe supported conservatives on the Brains Trust such as Raymond Moley and Adolf Berle, who feared such a measure would create very dangerous enemies. Roosevelt was worried that such action "might accentuate the national sense of panic and bewilderment".

Roosevelt summoned Congress into special session and presented it with an emergency banking bill that permitted the government to reopen the banks it ascertained to be sound, and other such banks as rapidly, as possible." The statue passed the House of Representatives by acclamation in a voice vote in forty minutes. In the Senate there was some debate and seven progressives, Robert LaFollette Jr, Huey P. Long, Gerald Nye, Edward Costigan, Henrik Shipstead, Porter Dale and Robert Davis Carey, voted against as they believed that it did not go far enough in asserting federal control.

On 9th March, 1933, Congress passed the Emergency Banking Relief Act. Within three days, 5,000 banks had been given permission to be re-opened. President Roosevelt gave the first of his radio broadcasts (later known as his "fireside chats"): "Some of our bankers have shown themselves either incompetent or dishonest in their handling of the people's funds. They had used money entrusted to them in speculations and unwise loans. This was, of course, not true of the vast majority of our banks, but it was true in enough of them to shock the people for a time into a sense of insecurity. It was the government's job to straighten out this situation and do it as quickly as possible. And the job is being performed. Confidence and courage are the essentials in our plan. We must have faith; you must not be stampeded by rumours. We have provided the machinery to restore our financial system; it is up to you to support and make it work. Together we cannot fail."

Will Rogers welcomed the speech: "Mr. Roosevelt stepped to the microphone last night and knocked another home run. His message was not only a great comfort to the people, but it pointed a lesson to all radio announcers and public speakers what to do with a big vocabulary - leave it at home in the dictionary. Our President took such a dry subject as banking (and when I say dry, I mean dry, for if it had been liquid, he wouldn't have to speak on it at all) and made everybody understand it, even the bankers."

Marriner Eccles was appointed as Governor of the Federal Reserve Board in November, 1934. The following year Eccles and Lauchlin Currie drafted a new banking bill to secure radical reform of the central bank for the first time since the formation of the Federal Reserve Board in 1913. It emphasized budget deficits as a way out of the Great Depression and it was fiercely resisted by bankers and the conservatives in the Senate. The banker, James P. Warburg commented that the bill was: "Curried Keynes... a large, half-cooked lump of J. Maynard Keynes... liberally seasoned with a sauce prepared by professor Lauchlin Currie."

With strong support from California bankers eager to undermine New York City domination of national banking, the 1935 Banking Act was passed by Congress. Over the next few years Eccles joined Harry Hopkins, Harold Ickes, Frances Perkins and Henry A. Wallace to continue increased government spending whereas Henry Morgenthau, James Farley and Daniel C. Roper urged President Roosevelt to balance the budget.

On this day in 1933 Anton Cermak, Mayor of Chicago, is assassinated. Anton Cermak was born in Kladno, Austria-Hungary (now Czech Republic), on 9th May, 1873. The following year his parents emigrated to the United States. After six years of formal schooling, Cermak, at the age of twelve, joined his father as a coal miner in Braidwood, Illinois.

Cermak developed a reputation for having strong views and he was selected to be the miner's spokesman in a demand for higher wages. This resulted in him losing his job and he decided to move to Chicago. He found work on the railways before starting his own business selling firewood. With his heavy-set physique and frightening temper he was an imposing man and was considered to have leadership qualities.

Cermak became active in the Democratic Party and in 1902 was elected to the state legislature. Seven years later Cermak became a Chicago City Council alderman. Cermak was able to use his inside knowledge of proposed government land purchase to speculate on real estate. He was also the founder of the Lawndale Building and Loan Association, director of the Lawndale National Bank and a partner in a real estate company Cermak and Serhant. His biographer, Alex Gottfried, claimed that because of his manner, he was popular with voters and seemed to "take pride in his own absence of polish."

Cermak became extremely wealthy and soon became leader of the party in the city. His main opponent was William Hale Thompson, the leader of the Republican Party in Chicago, and a man who was a close associate of Al Capone. Cermak maintained a reasonable relationship with Thompson, which allowed him to keep his patronage jobs and influence in the city. Even his enemies agreed that he was a hard-working politician who was "keenly aware of the most intricate details of the issues of the day".

In 1928 Cermak was selected as the Democrat candidate for the Senate. Although he ran a vigorous campaign but was defeated. It was a good year for the Republicans and Herbert Hoover had a landslide victory. Several states that had previously voted Democrat, such as Texas, Florida, Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia voted Republican for the first time. Al Smith won 40.8% of the vote compared to Hoover's 58.2%.

The Wall Street Crash in 1929 changed the political direction of the country. Cermak created what became known as the "modern Chicago Democratic Machine". It is claimed that Cermak was probably the first politicians to use statistical analysis to evaluate political performance and develop strategy. Members of the different wards were encouraged to compete with each other and success was rewarded with patronage jobs. Paul M. Green has argued that "never before had Chicagoans seen a political party so organized for battle."

In 1931 Cermak challenged William Hale Thompson, the Republican mayor of Chicago. Cermak accused Thompson of being under the control of Al Capone and other gangsters in the city. He campaigned for social reform and an end to prohibition. Thompson responded by calling Cermak a low-class foreigner. This was a dangerous tactic as at that this time two out of every three Chicagoans was either foreign born or the child of foreign born immigrants. In one speech Cermak commented: "Of course we couldn't all come over on the Mayflower. But I got here as soon as I could."

On 7th April, 1931, Cermak defeated Thompson, by nearly 200,000 votes. This included winning 45 of the city's 50 wards and this gave Cermak the largest victory in Chicago's history. During his time as mayor Cermak spent most of his time dealing with the consequences of the Great Depression. This included cutting services, laying off thousands of workers, and taking away vacation and sick pay from those who remained. To defend his policies Cermak conducted weekly radio talks that he called "intimate chats".

Cermak appointed James Allman as Chief of Police. He had been in the force for 30 years and enjoyed a reputation of being untainted by corruption. Sewell Avery described him as being as "clean as a whistle". The Chicago Crime Commission reported: "During the 12 years that the Chicago Crime Commission has been observing the Police Department there has not come to the notice a single adverse word as to Captain Allman's integrity, ability, efficiency, or independence." Allman was a great success and Chicago's murder rate actually dropped in 1931 and 1932, whereas most other major cities saw their rates rise.

Cermak attended the 1932 Democratic National Convention, that was held to select the presidential candidate. Cermak favoured Al Smith, mainly because he was opposed to Prohibition. This issue was a problem for Franklin D. Roosevelt because much of his support came from traditionally dry areas in the South and West whereas most party members and the general public favoured repeal. Roosevelt told his supporters to "vote as you wish" and that he would be happy to run on whatever platform the convention adopted. In the vote for repeal 934-213. Arthur Krock reported that "the Democratic party went as wet as the seven seas".

The first ballot showed Roosevelt with 666 votes - more than three times as many as his nearest rival but 104 short of victory. Roosevelt's campaign manager, James Farley, approached Cermak, who controlled most of Illinois delegation, about changing his vote. Cermak refused, because he was aware that if he abandoned the Irish-Catholic candidate, he would have trouble from his supporters in Chicago.

Roosevelt won the nomination on the fourth ballot when he won 945 votes. William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963) summed up the situation that the Democratic Party found itself in: "Liberal Democrats were somewhat uneasy about Roosevelt's reputation as a trimmer, and disturbed by the vagueness of his formulas for recovery, but no other serious candidate had such good claims on progressive support. as governor of New York, he had created the first comprehensive system of unemployment relief, sponsored an extensive program for industrial welfare, and won western progressives by expanding the work Al Smith had begun in conservation and public power."

Anton Cermak campaigned vigorously for Roosevelt in the the 1932 Presidential Election and delivered a 330,000 vote majority in Cook County. The turnout, almost 40 million, was the largest in American history. Roosevelt received 22,825,016 votes to Hoover's 15,758,397. With a 472-59 margin in the Electoral College, he captured every state south and west of Pennsylvania. Roosevelt carried more counties than a presidential candidate had ever won before, including 282 that had never gone Democratic. Of the forty states in Hoover's victory coalition four years before, the President held but six. Hoover received 6 million fewer votes than he had in 1928. The Democrats gained ninety seats in the House of Representatives to give them a large majority (310-117) and won control of the Senate (60-36).

Roosevelt was elected on 8th November, 1932, but the inauguration was not until 4th March, 1933. While he waited to take power, the economic situation became worse. Three years of depression had cut national income in half. Five thousand bank failures had wiped out 9 million savings accounts. By the end of 1932, 15 million workers, one out of every three, had lost their jobs. When the Soviet Union's trade office in New York issued a call for 6,000 skilled workers to go to Russia, more than 100,000 applied.

Cermak travelled to Miami on 7th February to have a meeting to discuss who was going to be appointed to Roosevelt's government. Cermak did not want a job for himself but was keen to get some of his followers to have good jobs. He also wanted to make sure Chicago got a share of Roosevelt's promised New Deal. Negotiations with James Farley went well and it was arranged that Roosevelt would meet with Cermak on 15th February at Bayfront Park.

Anton Cermak went to the meeting with James Bowler, another senior politician from Chicago. He later recalled: "Mayor Cermak and I had gone to the park twenty minutes before the President elect was due to arrive, and we sat in the band shell together. When Mr. Roosevelt's car came along the President elect saw the mayor and called to him to come down. Mr. Cermak called back that he would wait until after Mr. Roosevelt had made his speech. Then Roosevelt spoke, and he waited until the mayor came down from the platform to go to the side of the automobile."

Roosevelt explained how after the speech "I slid off the back of the car into my seat. Just then Mayor Cermak came forward. I shook hands and talked with him for nearly a minute. Then he moved off around the back of the car. Bob Clark (one of the Secret Servicemen) was standing right behind him to the right. As he moved off a man came forward with a telegram... and started telling me what it contained. While he was talking to me, I was leaning forward to the left side of the car."

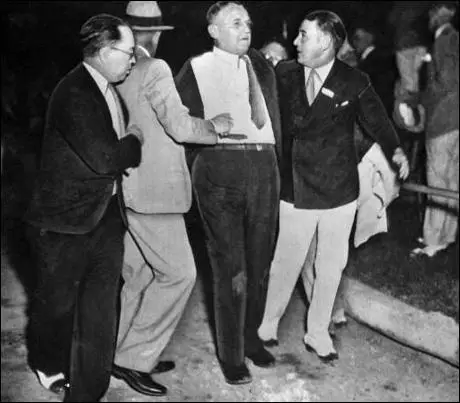

At that moment an Italian immigrant, Giuseppe Zangara, pointed his gun at Roosevelt. At the critical moment an alert spectator, Lillian Cross, hit the assassin's arm with her handbag and spoiled his aim. Zangara fired five shots and they all missed Roosevelt, but did hit others. This included Cermak who received a serious wound in the abdomen. Rex Schaeffer, a journalist working for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported: "I stood twenty-feet behind the car of the President-elect. Suddenly - I had given my attention to Mr. Roosevelt - a pistol blasted over my shoulder... Four more shots were fired and at the left of the car of Mr. Roosevelt I saw Mr. Cermak slump down."

Zangara was attacked by the crowd. "He was seized by men and women, dragged between the rows of seats, and then a policeman rushed through the crowd and swung on him with his blackjack. The Sherriff of Dade County, Dan Hardie, was on the platform and as the shots rang out he plunged into the crowd after the shooter, and with the policeman, jerked him errect and threw him on the trunk rack of a defective automobile which was carrying one of the wounded out of the park." Another witness remembers shouts of "Kill that man!" and "Don't let him get away".

L. L. Lee was standing next to Cermak when he was shot. He claimed that his only words were, "The president! Get him away!" Lee and W. W. Wood, a Democratic county committee member, grabbed his arms and walked him towards the president's car." The chauffeur decided to get away from the scene as quickly as possible. Lee then heard Roosevelt shout "For God's sake a man has been shot" and the "car jerked to a sudden stop."

Roosevelt told the New York Times: "I called to the chauffeur to stop. He did - about fifteen feet from where we started. The Secret Service man shouted to him to get out of the crowd and he started forward again. I stopped him a second time, this time at the corner of the bandstand, about thirty feet further on. I saw Mayor Cermak being carried. I motioned to have him put in the back of the car... Mayor Cermak was alive but I didn't think he was going to last. I put my left arm around him and my hand on his pulse, but I couldn't find any pulse... For three blocks I believed his heart had stopped. I held him all the way to the hospital and his pulse constantly improved."

After the shooting Roosevelt remained at Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami until Cermak was brought out of the emergency room. He spoke with him for several minutes and then visited the other shooting victims. According to the New York Tribune, an unnamed witness heard Cermak tell Roosevelt: "I'm glad it was me and not you, Mr. President."

Anton Cermak died three weeks later on 8th March, 1933. Giuseppe Zangara, an unemployed thirty-two-year-old bricklayer, claimed he acted alone. "I have always hated the rich and powerful. I do not hate Mr. Roosevelt personally. I hate all presidents, no matter from what country they come." After being found guilty was sentenced to death in the electric chair at the Florida State Penitentiary. When he heard his sentence he yelled at the judge, "You give me electric chair. I no afraid of that chair! You're one of capitalists. You is crook man too. Put me in electric chair. I no care!" Guiseppe Zangara was executed on 20th March, 1933.

Some political commentators such as Walter Winchell believed that Cermak was the real target. It was argued that Al Capone or William Hale Thompson had hired Zangara to assassinate Cermak. However, Blaise Picchi, the author of The Five Weeks of Giuseppe Zangara: The Man Who Would Assassinate FDR (2003) argued: "Federal agents conducted an exhaustive investigation of the shooting and could not find no link between Zangara and the Chicago mob."

Cermak's biographer, Alex Gottfried, is also convinced that Cermak was not an hired gunman: "What actually seems to be the case, is that, regardless of what connections might have existed between Cermak and Chicago gangdom, the shooting was neither planned by gangsters nor executed by a gangster hireling. The one way ride, the machine gun tattoo, the shotgun blast - these are their customary and foolproof methods. No plot similar to this shooting is recorded in the annals of gang murder."

In 1950 J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI, was asked to report on the original investigation into the case: "The Secret Service files reflected that there were many allegations, most of which were in the form of anonymous letters, that the attempted assassination was planned by gangsters or some organised criminal group, and that Zangara had been sent to Miami expressly for that purpose. Subsequent investigation, however, indicated that he had been in Miami for several months prior to the incident. There is no indication that Zangara had any knowledge as to the identity of Mayor Cermak of Chicago... There was no evidence that Zangara had been in Chicago nor had any relatives or associates in the city."

On this day in 1935 Oliver Wendell Holmes, died. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jnr, the son of Oliver Wendell Holmes, was born in Boston on 8th March, 1841. Holmes joined Union Army during the American Civil War and by the age of twenty he was first lieutenant in the 20th Massachusetts Regiment of Volunteers. He was seriously wounded three times and by the end of the war had reached the rank of captain.

In 1864 Holmes entered Harvard Law School and after graduating practised law in Boston. He also edited the American Law Review (1870-73) and Commentaries on American Law (1873) before becoming professor of law at Harvard University (1873-82).

Holmes became a national figure with the publication of his acclaimed book, The Common Law (1881). He was associate justice and then chief justice (1899-1902) of the Supreme Court of Massachusetts (1899-1902). In 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Holmes as a member of the Supreme Court and soon emerged as its leading liberal figure. A great advocate of free speech, he argued that the only reason for curtailing the right of freedom of speech was "clear and present danger" to the well-being of society.

New York Legislature passed a law that set the hours of bakers at no more than ten hours a day or sixty a week. In 1905 the owner of a bakery was fined $50 for violating the law. He appealed to the Supreme Court and it voted 5-4 that the law was unconstitutional. Holmes was one of the four justices who disagreed with the decision that was to hold back the passing of social welfare legislation.

In Supreme Court decisions Holmes often found himself in the minority with only John Harlan and Louis Brandeis supporting him on issues such as progressive social and labour legislation.

On this day in 1946 Ho Chi Minh signs an agreement with France which recognizes Vietnam as an autonomous state. During the Second World War the Vietminh received weapons and ammunition from the Soviet Union, and after the bombing of Pearl Harbour, they also obtained supplies from the United States. During this period the Vietminh leant a considerable amount about military tactics which was to prove invaluable in the years that were to follow.

When the Japanese surrendered to the Allies after the dropping of atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August, 1945, the Vietminh was in a good position to take over the control of the country.

In September, 1945, Ho Chi Minh announced the formation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Unknown to the Vietminh Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin had already decided what would happen to post-war Vietnam at a summit-meeting at Potsdam. It had been agreed that the country would be divided into two, the northern half under the control of the Chinese and the southern half under the British.

After the Second World War France attempted to re-establish control over Vietnam. In January 1946, Britain agreed to remove her troops and later that year, China left Vietnam in exchange for a promise from France that she would give up her rights to territory in China.

France refused to recognise the Democratic Republic of Vietnam that had been declared by Ho Chi Minh and fighting soon broke out between the Vietminh and the French troops. At first, the Vietminh under General Vo Nguyen Giap, had great difficulty in coping with the better trained and equipped French forces. The situation improved in 1949 after Mao Zedong and his communist army defeated Chaing Kai-Shek in China. The Vietminh now had a safe-base where they could take their wounded and train new soldiers.

By 1953 the Vietminh controlled large areas of North Vietnam. The French, however, had a firm hold on the south and had installed Bo Dai, the former Vietnamese Emperor, as the Chief of State.

When it became clear that France was becoming involved in a long-drawn out war, the French government tried to negotiate a deal with the Vietminh. They offered to help set-up a national government and promised they would eventually grant Vietnam its independence. Ho Chi Minh and the other leaders of the Vietminh did not trust the word of the French and continued the war.

French public opinion continued to move against the war. There were four main reasons for this: (1) Between 1946 and 1952 90,000 French troops had been killed, wounded or captured; (2) France was attempting to build up her economy after the devastation of the Second World War. The cost of the war had so far been twice what they had received from the United States under the Marshall Plan; (3) The war had lasted seven years and there was still no sign of an outright French victory; (4) A growing number of people in France had reached the conclusion that their country did not have any moral justification for being in Vietnam.

General Navarre, the French commander in Vietnam, realised that time was running out and that he needed to obtain a quick victory over the Vietminh. He was convinced that if he could manoeuvre General Vo Nguyen Giap into engaging in a large scale battle, France was bound to win. In December, 1953, General Navarre setup a defensive complex at Dien Bien Phu, which would block the route of the Vietminh forces trying to return to camps in neighbouring Laos. Navarre surmised that in an attempt to reestablish the route to Laos, General Giap would be forced to organise a mass-attack on the French forces at Dien Bien Phu.

Navarre's plan worked and General Giap took up the French challenge. However, instead of making a massive frontal assault, Giap choose to surround Dien Bien Phu and ordered his men to dig a trench that encircled the French troops. From the outer trench, other trenches and tunnels were dug inwards towards the centre. The Vietminh were now able to move in close on the French troops defending Dien Bien Phu.

While these preparations were going on, Giap brought up members of the Vietminh from all over Vietnam. By the time the battle was ready to start, Giap had 70,000 soldiers surrounding Dien Bien Phu, five times the number of French troops enclosed within.

Employing recently obtained anti-aircraft guns and howitzers from China, Giap was able to restrict severely the ability of the French to supply their forces in Dien Bien Phu. When Navarre realised that he was trapped, he appealed for help. The United States was approached and some advisers suggested the use of tactical nuclear weapons against the Vietminh. Another suggestion was that conventional air-raids would be enough to scatter Giap's troops.

The United States President, Dwight Eisenhower, however, refused to intervene unless he could persuade Britain and his other western allies to participate. Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, declined claiming that he wanted to wait for the outcome of the peace negotiations taking place in Geneva before becoming involved in escalating the war.

On March 13, 1954, Vo Nguyen Giap launched his offensive. For fifty-six days the Vietminh pushed the French forces back until they only occupied a small area of Dien Bien Phu. Colonel Piroth, the artillery commander, blamed himself for the tactics that had been employed and after telling his fellow officers that he had been "completely dishonoured" committed suicide by pulling the safety pin out of a grenade.

The French surrendered on May 7th. French casualties totalled over 7,000 and a further 11,000 soldiers were taken prisoner. The following day the French government announced that it intended to withdraw from Vietnam. The following month the foreign ministers of the United States, the Soviet Union, Britain and France decided to meet in Geneva to see if they could bring about a peaceful solution to the conflicts in Korea and Vietnam.

After much negotiation the following was agreed: (1) Vietnam would be divided at the 17th parallel; (2) North Vietnam would be ruled by Ho Chi Minh; (3) South Vietnam would be ruled by Ngo Dinh Diem, a strong opponent of communism; (4) French troops would withdraw from Vietnam; (5) the Vietminh would withdraw from South Vietnam; (6) the Vietnamese could freely choose to live in the North or the South; and (7) a General Election for the whole of Vietnam would be held before July, 1956, under the supervision of an international commission.

After their victory at Dien Bien Phu, some members of the Vietminh were reluctant to accept the cease-fire agreement. Their main concern was the division of Vietnam into two sections. However, Ho Chi Minh argued that this was only a temporary situation and was convinced that in the promised General Election, the Vietnamese were sure to elect a communist government to rule a re-united Vietnam.

This view was shared by President Dwight Eisenhower. As he wrote later: "I have never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs who did not agree that had elections been held at the time of the fighting, possibly 80 per cent of the population would have voted for the communist Ho Chi Minh."

When the Geneva conference took place in 1954, the United States delegation proposed the name of Ngo Dinh Diem as the new ruler of South Vietnam. The French argued against this claiming that Diem was "not only incapable but mad". However, eventually it was decided that Diem presented the best opportunity to keep South Vietnam from falling under the control of communism.

When it became clear that Ngo Dinh Diem had no intention of holding elections for a united Vietnam, his political opponents began to consider alternative ways of obtaining their objectives. Some came to the conclusion that violence was the only way to persuade Diem to agree to the terms of the 1954 Geneva Conference. The year following the cancelled elections saw a large increase in the number of people leaving their homes to form armed groups in the forests of Vietnam. At first they were not in a position to take on the South Vietnamese Army and instead concentrated on what became known as 'soft targets'. In 1959, an estimated 1,200 of Diem's government officials were murdered.

Ho Chi Minh was initially against this strategy. He argued that the opposition forces in South Vietnam should concentrate on organising support rather than carrying out acts of terrorism against Diem's government.

In 1959, Ho Chi Minh sent Le Duan, a trusted adviser, to visit South Vietnam. Le Duan returned to inform his leader that Diem's policy of imprisoning the leaders of the opposition was so successful that unless North Vietnam encouraged armed resistance, a united country would never be achieved.

Ho Chi Minh agreed to supply the guerrilla units with aid. He also encouraged the different armed groups to join together and form a more powerful and effective resistance organisation. This they agreed to do and in December, 1960, the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF) was formed. The NLF, or the 'Vietcong', as the Americans were to call them, was made up of over a dozen different political and religious groups. Although the leader of the NLF, Hua Tho, was a non-Marxist, Saigon lawyer, large numbers of the movement were supporters of communism.

The strategy and tactics of the NLF were very much based on those used by Mao Zedong in China. This became known as Guerrilla Warfare. The NLF was organised into small groups of between three to ten soldiers. These groups were called cells. These cells worked together but the knowledge they had of each other was kept to the bare minimum. Therefore, when a guerrilla was captured and tortured, his confessions did not do too much damage to the NLF.

The initial objective of the NLF was to gain the support of the peasants living in the rural areas. According to Mao Zedong, the peasants were the sea in which the guerrillas needed to swim: "without the constant and active support of the peasants... failure is inevitable."

When the NLF entered a village they obeyed a strict code of behaviour. All members were issued with a series of 'directives'. These included:" (1) Not to do what is likely to damage the land and crops or spoil the houses and belongings of the people; (2) Not to insist on buying or borrowing what the people are not willing to sell or lend; (3) Never to break our word; (4) Not to do or speak what is likely to make people believe that we hold them in contempt; (5) To help them in their daily work (harvesting, fetching firewood, carrying water, sewing, etc.)."

Three months after being elected president in 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson launched Operation Rolling Thunder. The plan was to destroy the North Vietnam economy and to force her to stop helping the guerrilla fighters in the south. Bombing was also directed against territory controlled by the NLF in South Vietnam. The plan was for Operation Rolling Thunder to last for eight weeks but it lasted for the next three years. In that time, the US dropped 1 million tons of bombs on Vietnam.

On this day in 1951 the trial of Julius Rosenberg, Ethel Rosenberg and Morton Sobell begins. Irving Saypol opened the case: "The evidence will show that the loyalty and allience of the Rosenbergs and Sobell were not to our country, but that it was to Communism, Communism in this country and Communism throughout the world... Sobell and Julius Rosenberg, classmates together in college, dedicated themselves to the cause of Communism... this love of Communism and the Soviet Union soon led them into a Soviet espionage ring... You will hear our Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Sobell reached into wartime projects and installations of the United States Government... to obtain... secret information... and speed it on its way to Russia.... We will prove that the Rosenbergs devised and put into operation, with the aid of Soviet... agents in the country, an elaborate scheme which enabled them to steal through David Greenglass this one weapon, that might well hold the key to the survival of this nation and means the peace of the world, the atomic bomb."

The first witness of the prosecution was Max Elitcher. He had met Morton Sobell at Stuyvesant High School in New York City. Later they both studied electrical engineering at the College of the City of New York (CCNY). A fellow student at the CCNY was Julius Rosenberg. After graduation Elitcher and Sobell both found jobs at the Navy Bureau of Ordnance in Washington, where they shared an apartment and joined the Communist Party of the United States.

Elitcher claimed that in June 1944, he was phoned by Rosenberg: "I remembered the name, I recalled who it was, and he said he would like to see me. He came over after supper, and my wife was there and we had a casual conversation. After that he asked if my wife would leave the room, that he wanted to speak to me in private." Rosenberg then allegedly said that many people, including Sobell, were aiding Russia "by providing classified information about military equipments".

At the beginning of September 1944, Elitcher and his wife went on holiday with Sobell and his fiancee. Elitcher told his friend of Rosenberg's visit and his disclosure that "you, Sobell, were also helping in this." According to Elitcher, Sobell "became very angry and said "he should not have mentioned my name. He should not have told you that." Elitcher claimed that Rosenberg tried to recruit him again in September 1945. Rosenberg told Elitcher "that even though the war was over there was a continuing need for new military information for Russia."

Elitcher was approached by Sobell in 1947 who asked him if he "knew of any engineering students or engineering graduates who were progressive, who would be safe to approach on this question of espionage. When he decided to quit his Navy job in Washington in June 1948, Rosenberg tried to dissuade him as "he needed somebody to work at the Navy Department for this espionage purpose." When Elitcher refused to stay on, Rosenberg suggested that he get a job where military work was being done.

David Greenglass was questioned by the chief prosecutor assistant, Roy Cohn. Greenglass claimed that his sister, Ethel, influenced him to become a Communist. He remembered having conversations with Ethel at their home in 1935 when he was thirteen or fourteen. She told him that she preferred Russian socialism to capitalism. Two years later, her boyfriend, Julius, also persuasively talked about the merits of Communism. As a result of these conversations he joined the Young Communist League (YCL).

Greenglass pointed out that Julius Rosenberg recruited him as a Soviet spy in September 1944. Over the next few months he provided some sketches and provided a written description of the lens mold experiments and a list of scientists working on the project. He was gave Rosenberg the names of "some possible recruits... people who seemed sympathetic with Communism." Greenglass also claimed that because of his poor handwriting his sister typed up some of the material.

In June 1945 Greenglass claimed that Harry Gold visited him. "There was a man standing in the hallway who asked if I were Mr. Greenglass, and I said yes. He steeped through the door and he said, Julius sent me... and I walked to my wife's purse, took out the wallet and took out the matched part of the Jello box." Gold then produced the other part and he and David checked the pieces and saw they fitted. Greenglass did not have the information ready and asked Gold to return in the afternoon. He then prepared sketches of lens mold experiments with written descriptive material. When he returned Greenglass gave him the material in an envelope. Gold also gave Greenglass an envelope containing $500.

Greenglass told the court that in February 1950, Julius Rosenberg came to see him. He gave him the news that Klaus Fuchs had been arrested and that he had made a full confession. This would mean that members of his Soviet spy network would also be arrested. According to Greenglass, Rosenberg suggested that he should leave the country. Greenglass replied: "Well, I told him that I would need money to pay my debts back... to leave with a clear head... I insisted on it, so he said he would get the money for me from the Russians." In May he gave him $1,000 and promised him $6,000 more. (He later gave him another $4,000.) Rosenberg also warned him that Harry Gold had been arrested and was also providing information about the spy ring. Rosenberg also said he had to flee as the FBI had identified Jacob Golos as a spy and he had been his main contact until his death in 1943.

Greenglass was cross-examined by Emanuel Bloch and suggested that his hostility towards Rosenberg had been caused by their failed business venture: "Now, weren't there repeated quarrels between you and Julius when Julius accused you of trying to be a boss and not working on machines?" Greenglass replied: "There were quarrels of every type and every kind... arguments over personality... arguments over money... arguments over the way the shop was run... We remained as good friends in spite of the quarrels." Bloch asked him why he had punched Rosenberg while in a "candy shop." Greenglass admitted that "it was some violent quarrel over something in the business." Greenglass complained that he had lost all of his money in investing in Rosenberg's business.

The New York Times reported that Ruth Greenglass, the mother of a boy, four, and a girl, ten months, was a "buxom and self-possessed brunette" but looked older and her twenty-six years. It added that she testified "in seemingly eager, rapid fashion." (30) Ruth Greenglass recalled a conversation she had with Julius Rosenberg in November 1944: "Julius said that I might have noticed that for some time he and Ethel had not been actively pursuing any Communist Party activities, that they didn't buy the Daily Worker at the usual newsstand; that for two years he had been trying to get in touch with people who would assist him to be able to help the Russian people more directly other than just his membership in the Communist Party... He said that his friends had told him that David was working on the atomic bomb, and he went on to tell me that the atomic bomb was the most destructive weapon used so far, that it had dangerous radiation effects that the United States and Britain were working on this project jointly and that he felt that the information should be shared with Russia, who was our ally at the time, because if all nations had the information then one nation couldn't use the bomb as a threat against another. He said that he wanted me to tell my husband, David, that he should give information to Julius to be passed on to the Russians."

Ruth Greenglass admitted that in February 1945, Rosenberg paid her to go and live in Albuquerque so she was close to David Greenglass who was working in Los Alamos: "Julius said he would take care of my expenses; the money was no object; the important thing was for me to go to Albuquerque to live." Harry Gold would visit and exchange information for money. One payment in June was $500. She "deposited $400 in an Albuquerque bank, purchased a $50 defense bond (for $37.50)" and used the rest for "household expenses."

Ruth Greenglass testified that she saw a "mahogany console table" in the Rosenberg's apartment in 1946. "Julius said it was from his friend and it was a special kind of table, and he turned the table on its side." A portion of the table was hollow "for a lamp to fit underneath it so that the table could be used for photograph purposes." Greenglass claimed that Rosenberg said he used the table to take "pictures on microfilm of the typewritten notes."

At the trial Harry Gold admitted that he became a Soviet spy in 1935. Time Magazine reported that "as precisely and matter-of-factly as a high-school teacher explaining a problem in geometry". During the Second World War his main contact was Anatoli Yatskov. In January 1945 he met Klaus Fuchs at his sister's house in Cambridge, Massachusetts. "Fuchs was now stationed at a place called Los Alamos, New Mexico; that this was a large experimental station.... Fuchs told me that a tremendous amount of progress had been made. In addition, he had made mention of a lens, which was being worked on as a part of the atom bomb.... Yatskov told me to try to remember anything else that Fuchs had mentioned during our Cambridge meeting, about the lens."

Yatskov told Gold to arrange a meeting with David Greenglass in Albuquerque. Yatskov then handed Gold a sheet of onionskin paper "and on it was typed... the name Greenglass." According to Gold the last thing on the paper was "Recognition signal. I come from Julius." Yatskov also gave Gold an odd-shaped "piece of cardboard, which appeared to have been cut from a packaged food of some sort" and said that Greenglass would have the matching piece. An envelope, which Yatskov said contained $500, was to be given to Greenglass or his wife.

Gold met Greenglass on 3rd June, 1945. "I saw a man of about 23... I said I came from Julius... I showed him the piece of cardboard... that had been given me by Yatskov... He asked me to enter. I did. Greenglass went to a women's handbag and brought out from it a piece of cardboard. We matched the two of them." The New York Times reported: "By an ironic quick of Gold's testimony, the cut-out portion of a Jello box became the first tangible bit of evidence to connect the Rosenbergs, the Greenglasses, Gold and Yatskov."

On 26th December 1946, Harry Gold met Anatoli Yatskov in New York City. Gold told him he was now working for Abraham Brothman, a Soviet spy who had been named by Elizabeth Bentley as a spy. Yatskov was furious and he said: "You fool... You spoiled eleven years of work." Gold claimed in court that Yatskov "kept mumbling that I had created terrible damage and... then told me that he would not see me in the United States again." Records show that Yatskov and his family left the United States by ship on 27th December.

Elizabeth Bentley worked closely with Jacob Golos, Julius Rosenberg's main Soviet contact. She recalled that in the autumn of 1942 she accompanied Golos when he drove to Knickerbocker Village and told her "he had to stop by to pick up some material from a contact, an enginner." While she waited, Golos had met the contact and "returned to the car with an envelope of material."

Irving Saypol asked Bentley: "Subsequent to this occasion when you went to the vicinity of Knickerbocker Village with Golos.... did you have a telephone call from somebody who described himself as Julius?" She replied that on five of six occasions in 1942 and 1943 she received phone calls from a man called Julius. These messages were passed on to Golos. Judge Irving Kaufman commented that it would "be for the jury to infer... whether or not the Julius she spoke to... is the defendant Julius Rosenberg."

Julius Rosenberg was asked if he had ever been a member of the Communist Party on the United States. Rosenberg replied by invoking the Fifth Amendment. After further questioning he agreed that he sometimes read the party newspaper, the Daily Worker. He was also asked about his wartime views regarding the Soviet Union. He replied that he "felt that the Russians contributed the major share in destroying the Nazi army" and "should get as much help as possible." His opinion was "that if we had a common enemy we should get together commonly." He also admitted that he had been a member of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee.

Rosenberg was asked about the "mahogany console table" claimed by Ruth Greenglass to be in the Rosenberg's apartment in 1946. Rosenberg claimed he had purchased it from Macy's for $21. Irving Saypol replied: "Don't you know, Mr. Rosenberg, that you couldn't buy a console table in Macy's... in 1944 and 1945, for less than $85?" This was later found to be incorrect but at the time the impression was given that Rosenberg was lying.

The "mahogany console table" was not presented in the courtroom as evidence. It was claimed that it had been lost. Therefore it was not possible to examine it to see if Greenglass was right when she said that a portion of the table was hollow "for a lamp to fit underneath it so that the table could be used for photograph purposes." Aftter the case had finished it the table was found and it did not have the section claimed by Greenglass. A brochure was also produced to suggest that Rosenberg might have purchased it for $21 at Macy's.

Ethel Rosenberg was the final defence witness. The New York Times described her in court as a "little woman with soft and pleasant features". During cross-examination she denied all allegations regarding espionage activity. She admitted that she owned a typewriter - she had purchased it when she was eighteen - and during her courtship had typed Julius's college engineering reports and prior to the birth of her first child, she did "a lot of typing" as secretary for the East Side Defense Council and the neighborhood branch of the Civil Defense Volunteer Organization. However, she insisted that she never had typed anything relating to government secrets.

Irving Saypol pointed out that she had testified twice before the grand jury and both times she had invoked her constitutional privilege against self-incrimination. Much of her grand jury testimony was read in court, disclosing that many of the same questions she had refused to answer before the grand jury she later answered at her trial. The New York Times reported that she "had claimed constitutional privilege... even on questions that seemed harmless." Ethel gave no specific explanation for her extensive use of the Fifth Amendment before the grand jury, but noted that both her husband and brother were under arrest at the time.

Several journalists covering the trial noticed that no FBI agents were called to testify. The reason for this was that if they appeared the lawyers could have asked questions and the answers would have been very unfavourable to the prosecution. "For instance, what was the evidence of espionage activity against Ethel Rosenberg? Just one question of this kind could make the entire structure disintegrate."

Emanuel Bloch argued: "Is there anything here which in any way connects Rosenberg with this conspiracy? The FBI "stopped at nothing in their investigation... to try to find some piece of evidence that you could feel, that you could see, that would tie the Rosenbergs up with this case... and yet this is the... complete documentary evidence adduced by the Government... this case, therefore, against the Rosenbergs depends upon oral testimony."

Bloch attacked David Greenglass, the main witness against the Rosenbergs. Greenglass was "a self-confessed espionage agent," was "repulsive... he smirked and he smiled... I wonder whether... you have ever come across a man, who comes around to bury his own sister and smiles." Bloch argued that Greenglass's "grudge against Rosenberg" over money was not enough to explain his testimony. The explanation was that Greenglass "loved his wife" and was "willing to bury his sister and his brother-in-law" to save her. The "Greenglass Plot" was to lessen his punishment by pointing his finger at someone else. Julius Rosenberg was a "clay pigeon" because he had been fired from his government job for being a member of the Communist Party of the United States in 1945.

In his reply, Irving Saypol, pointed out that "Mr Bloch had a lot of things to say about Greenglass... but the story of the Albuquerque meeting... does not come to you from Greenglass alone. Every word that David and Ruth Greenglass spoke on this stand about that incident was corroborated by Harry Gold... a man concerning whom there cannot even be a suggestion of motive... He had been sentenced to thirty years... He can gain nothing from testifying as he did in this courtroom and tried to make amends. Harry Gold, who furnished the absolute corroboration of the testimony of the Greenglasses, forged the necessary link in the chain that points indisputably to the guilt of the Rosenbergs."

In his summing up Judge Irving Kaufman was considered by many to have been highly subjective: "Judge Kaufman tied the crimes the Rosenbergs were being accused of to their ideas and the fact that they were sympathetic to the Soviet Union. He stated that they had given the atomic bomb to the Russians, which had triggered Communist aggression in Korea resulting in over 50,000 American casualties. He added that, because of their treason, the Soviet Union was threatening America with an atomic attack and this made it necessary for the United States to spend enormous amounts of money to build underground bomb shelters."

The jury found all three defendants guilty. Thanking the jurors, Judge Kaufman, told them: "My own opinion is that your verdict is a correct verdict... The thought that citizens of our country would lend themselves to the destruction of their own country by the most destructive weapons known to man is so shocking that I can't find words to describe this loathsome offense." Judge Kaufman sentenced Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to the death penalty and Morton Sobell to thirty years in prison.

A large number of people were shocked by the severity of the sentence as they had not been found guilty of treason. In fact, they had been tried under the terms of the Espionage Act that had been passed in 1917 to deal with the American anti-war movement. Under the terms of this act, it was a crime to pass secrets to the enemy whereas these secrets had gone to an ally, the Soviet Union. During the Second World War several American citizens were convicted of passing information to Nazi Germany. Yet none of these people were executed.

It soon became clear that the main objective of imposing the death penalty was to persuade Julius Rosenberg and others to confess. Howard Rushmore, writing in the New York Journal-American, he argued: "A few months in the death house might loosen the tongues of one or more of the three traitors and lead to the arrest of... other Americans who were part of the espionage apparatus." Eugene Lyons commented in the New York Post: "The Rosenbergs still have a chance to save their necks by making full disclosure about their spy ring - for Judge Kaufman, who conducted the trial so ably, has the right to alter his death sentence."

J. Edgar Hoover was one of those who opposed the sentence. As Curt Gentry, the author of J. Edgar Hoover, The Man and the Secrets (1991) has pointed out: "While he thought the arguments against executing a woman were nothing more than sentimentalism, it was the 'psychological reaction' of the public to executing a wife and mother and leaving two small children orphaned that he most feared. The backlash, he predicted, would be an avalanche of adverse criticism, reflecting badly on the FBI, the Justice Department, and the entire government."

However, the vast majority of newspapers in the United States supported the death-sentence of the Rosenbergs. Only the Daily Worker, the journal of the Communist Party of the United States, and the Jewish Daily Forward took a strong stance against the decision. Julius Rosenberg wrote to Ethel that he was "amazed" by the "newspaper campaign organized against us". However, he insisted that "we will never lend ourselves to the tools to implicate innocent people, to confess crimes we never did and to help fan the flames of hysteria and help the growing witch hunt." In another letter five days later he pointed out that it was "indeed a tragedy how the lords of the press can mold public opinion by printing... blatant falsehoods."

Dorothy Thompson was one of the only columnists who complained that the sentence was too harsh. Writing in The Washington Star she argued: "The death sentence... depresses me... in 1944, we were not at war with the Soviet Union... Indeed, it is unlikely that had they been tried in 1944 they would have received any such sentence." (50) Thompson's views were unpopular in the United States, it did reflect the views being expressed in other countries. The case created a great deal of controversy in Europe where it was argued that the Rosenbergs were victims of anti-semitism and McCarthyism.

Judge Irving Kaufman suggested that the campaign against the death sentences was part of a communist conspiracy. "I have been frankly hounded, pounded by vilification and by pressurists... I think that it is not a mere accident that some people have been aroused in these countries. I think it has been by design." Time Magazine took a similar view and argued "Communists the world over... had an issue they rode hard... the American couple who sit in the death house at Sing Sing, scheduled to be electrocuted." However, the The New York Tribune pointed out that it was not only communists who were complaining about the death sentences: "The vast majority of non-Communist newspapers in France continued to urge today that the death sentences of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg... be commuted to life imprisonment."

In December 1952 the Rosenbergs appealed their sentence. Myles Lane, for the prosecution argued: "In my opinion, your Honor, this and this alone accounts for the stand which the Russians took in Korea, which... caused death and injury to thousands of American boys and untold suffering to countless others, and I submit that these deaths and this suffering, and the rest of the state of the world must be attributed to the fact that the Soviets do have the atomic bomb, and because they do... the Rosenbergs made a tremendous contribution to this despicable cause. If they (the Rosenbergs) wanted to cooperate... it would lead to the detection of any number of people who, in my opinion, are today doing everything that they can to obtain additional information for the Soviet Union... this is no time for a court to be soft with hard-boiled spies.... They have showed no repentance; they have stood steadfast in their insistence on their innocence."

Judge Irving Saypol agreed and responded with the judgment: "I am again compelled to conclude that the defendants' guilt... was established beyond doubt... Their traitorous acts were of the highest degree... It is apparent that Russia was conscious of the fact that the United States had the one weapon which gave it military superiority and that, at any price, it had to wrest that superiority from the United States by stealing the secret information concerning that weapon... Neither defendant has seen fit to follow the course of David Greenglass and Harry Gold. Their lips have remained sealed and they prefer the glory which they believe will be theirs by the martyrdom which will be bestowed upon them by those who enlisted them in this diabolical conspiracy (and who, indeed, desire them to remain silent)... I still feel that their crime was worse than murder... The application is denied."

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg now appealed their sentence to President Harry S. Truman. However, Truman vacated the Presidency on 20th January, 1953, without acting on the Rosenbergs's clemency appeals. He had passed the problem to his successor, Dwight D. Eisenhower. It was reported that he received nearly fifteen thousand clemency letters in the first week of his administration. He received a great deal of advice from columnists in the press. George E. Sokolsky, wrote in the New York Journal-American: "Everything has been tried by the Rosenbergs except the only step that can justify their existence as human beings: they have never confessed; they have shown no contrition; they have not been penitent. They have been arrogant and tight-lipped... It is impossible to forgive these spies; it would be possible to commute their sentences, if they told the story fully, more than we now know even after these trials... Klaus Fuchs confessed. David Greenglass confessed. Harry Cold confessed. The Rosenbergs remain adamant... let them go to the devil."

President Eisenhower made his decision on 11th February, 1953: "I have given earnest consideration to the records in the case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and to the appeals for clemency made on their behalf.... The nature of the crime for which they have been found guilty and sentenced far exceeds that of the taking of the life of another citizen: it involves the deliberate betrayal of the entire nation and could very well result in the death of many, many thousands of innocent citizens. By their act these two individuals have in fact betrayed the cause of freedom for which free men are fighting and dying at this very hour.... There has been neither new evidence nor have there been mitigating circumstances which would justify altering this decision, and I have determined that it is my duty, in the interest of the people of the United States, not to set aside the verdict of their representatives."

In a letter to his son, Eisenhower went into more detail about his decision: "It goes against the grain to avoid interfering in the case where a woman is to receive capital punishment. Over against this, however, must be placed one or two facts that have greater significance. The first of these is that in this instance it is the woman who is the strong and recalcitrant character, the man is the weak one. She has obviously been the leader in everything they did in the spy ring. The second thing is that if there would be any commuting of the woman's sentence without the man's then from here on the Soviets would simply recruit their spies from among women."

Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg remained on death row for twenty-six months. Two weeks before the date scheduled for their deaths, the Rosenbergs were visited by James V. Bennett, the Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons. After the meeting they issued a statement: "Yesterday, we were offered a deal by the Attorney General of the United States. We were told that if we cooperated with the Government, our lives would be spared. By asking us to repudiate the truth of our innocence, the Government admits its own doubts concerning our guilt. We will not help to purify the foul record of a fraudulent conviction and a barbaric sentence. We solemnly declare, now and forever more, that we will not be coerced, even under pain of death, to bear false witness and to yield up to tyranny our rights as free Americans. Our respect for truth, conscience and human dignity is not for sale. Justice is not some bauble to be sold to the highest bidder. If we are executed it will be the murder of innocent people and the shame will be upon the Government of the United States."

The case went before the Supreme Court. Three of the Justices, William Douglas, Hugo Black and Felix Frankfurter, voted for a stay of execution because they agreed with legal representation that the Rosenbergs had been tried under the wrong law. It was claimed that the 1917 Espionage Act, under which the couple had been indicted and sentenced, had been superseded by the penalty provisions of the 1946 Atomic Energy Act. Under the latter act, the death sentence may be imposed only when a jury recommends it and the offense was committed with intent to injure the United States. However, the other six voted for the execution to take place.

The Rosenbergs were executed on 19th June, 1953. "Julius Rosenberg, thirty-five, wordlessly went to his death at 8:06 P.M. Ethel Rosenberg, thirty-seven, entered the execution chamber a few minutes after her husband's body had been removed. Just before being seated in the chair, she held out her hand to a matron accompanying her, drew the other woman close, and kissed her lightly on the cheek. She was pronounced dead at 8:16 P.M." According to the New York Times the Rosenbergs went to their deaths "with a composure that astonished the witnesses."

The execution resulted in large protests all over Europe. Jean-Paul Sartre wrote in Libération: "Now that we have been made your allies, the fate of the Rosenbergs could be a preview of our own future. You, who claim to be masters of the world, had the opportunity to prove that you were first of all masters of yourselves. But if you gave in to your criminal folly, this very folly might tomorrow throw us headlong into a war of extermination... By killing the Rosenbergs you have quite simply tried to halt the progress of science by human sacrifice. Magic, witch hunts, auto-da-fe's, sacrifices - we are here getting to the point: your country is sick with fear... you are afraid of the shadow of your own bomb."

This was in direct contrast to the way the American media dealt with the issue. The New York Times reported the day after the execution: "In the record of espionage against the United States there had been no case of its magnitude and its stern drama. The Rosenbergs were engaged in funneling the secrets of the most destructive weapon of all time to the most dangerous antagonist the United States ever confronted - at a time when a deadly atomic arms race was on. Their crime was staggering in its potential for destruction. It stirred the fears and the emotions of the American people... The prevailing opinion in the United States... is that the Rosenbergs for two years had access to every court in the land and every organ of public opinion, that no court found grounds for doubting their guilt, that they were the only atom spies who refused to confess and that they got what they deserved."

The execution of Ethel Rosenberg caused particular concern. Jacques Monod argued in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: "We could not understand that Ethel Rosenberg should have been sentenced to death when the specific acts of which she was accused were only two conversations; and we were unable to accept the death sentence as being justified by the 'moral support' she was supposed to have given her husband. In fact the severity of the sentence, even if one provisionally accepted the validity of the Greenglass testimony, appeared out of all measure and reason to such an extent as to cast doubt on the whole affair, and to suggest that nationalistic passions and pressure from an inflamed public opinion, had been strong enough to distort the proper administration of justice."

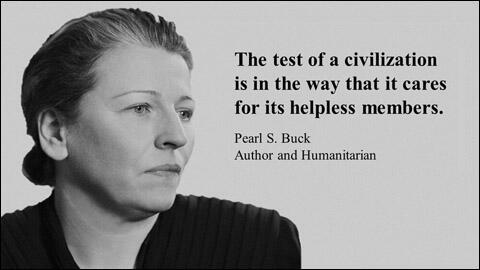

On this day in 1973 Pearl S. Buck died of lung cancer in Danby, Vermont. Pearl Buck (Sydenstricker) was born in Hillsboro, West Virginia on 26th June, 1892. The daughter of Presbyterian missionaries, Absalom Sydenstricker (1852-1931) and Caroline Stulting (1857–1921), was raised in Zhenjiang.

Buck returned to the United States in 1911 and studied at Randolph-Macon Woman's College. Buck developed left-wing political views at university and was a strong supporter of women's suffrage.

In 1914 Buck returned to China and three years later married an agricultural economist missionary, John Lossing Buck. The couple moved to Suzhou, a small town on the Huai River.

In 1920 the Bucks moved to Nanjing. Pearl taught English Literature at Nanjing University and the Chinese National University. In 1924, they returned to the United States where Pearl earned her Masters degree from Cornell University. The following year they returned to China.

Pearl Buck's first novel, East Wind: West Wind, was published in 1930. This was followed by the highly successful The Good Earth (1931). It won the Pulitzer Prize "for her rich and truly epic descriptions of peasant life in China". It also inspired a Broadway play and an award-winning film.

In 1934, the Bucks moved back to the United States. The following year she divorced John Lossing Buck and married Richard Walsh, the president of the John Day Company and her publisher. In 1935, she bought a sixty-acre homestead she called Green Hills Farm in Pennsylvania and moved into the one hundred year-old farmhouse on the property with her second husband and their family of six children. Pearl Buck continued to write novels and this included The Mother (1934), House of Earth (1935), The Exile (1936), Fighting Angel (1936) and The Proud Heart (1938).

Buck was a strong advocate of women's rights and wrote essays such as Of Men and Women (1941) and American Unity and Asia (1942) where she warned that racist and sexist attitudes would damage long-term prospects of peace in Asia. She also helped left-wing writers, Edgar Snow, Agnes Smedley and Anna Louise Strong reach American audiences.

After the Second World War Buck became a strong critic of American foreign policy. Robert Shaffer has argued: "Buck's early writings portrayed the subordination of Chinese women, but by the late 1930s she was also highly critical of formal and informal discrimination against women in the United States. While consistantly critical of Stalinism, Buck was an early opponent of the Cold War and of the American military build-up in the late 1940s, warning of American tendencies toward fascism." Buck also advocated recognition of the People's Republic of China and opposed U.S. policy in the Korean War.

Other novels by Pearl S. Buck included Dragon Seed (1942), Townsman (1945), Pavilion of Women (1946), A Long Love (1949), God's Men (1951), The Hidden Flower (1952), Come, My Beloved (1953), Imperial Women (1956), Letter from Peking (1957), Command the Morning (1959), The Living Reed (1963), Death in the Castle (1965), The Time Is Noon (1966), The New Year (1968), The Three Daughters of Madame Liang (1969) and Mandala (1970).

On this day in 1975 the Zapruder film of the assassination of John F. Kennedy is shown to a national TV audience. On 22nd November, 1963, Abraham Zapruder filmed the motorcade of President Kennedy. He later explained to Wesley J. Liebelerabout the background to the filming. "I didn't have my camera but my secretary (Lillian Rogers) asked me why I don't have it and I told her I wouldn't have a chance even to see the President and somehow she urged me and I went home and got my camera."

According to Jim Marrs: "Zapruder made a fourteen-mile round trip drive home to pick up his camera.By the time he returned, crowds were already gathering to watch the motorcade." Zapruder told the Warren Commission: "I thought I might take pictures from the window because my building is right next to the building where the alleged assassin was, and it's just across 501 Elm Street, but I figured - I may go down and get better pictures, and I walked down. I believe it was Elm Street and on down to the lower part, closer to the underpass and I was trying to pick a space from where to take those pictures and I tried one place and it was on a narrow ledge and I couldn't balance myself very much. I tried another place and that had some obstruction of signs or whatever it was there and finally I found a place farther down near the underpass that was a square of concrete I don't know what you call it maybe about 4 feet high." Zapruder decided to take his receptionist, Marilyn Sitzman, with him to Dealey Plaza.

Abraham Zapruder went on to tell Wesley J. Liebeler: "I heard the first shot and I saw the President lean over and grab himself like this (holding his left chest area)... I thought I heard two (shots), it could be three, because to my estimation I thought he was hit on the second - I really don't know. The whole thing that has been transpiring - it was very upsetting and as you see I got a little better all the time and this came up again and it to me looked like the second shot, but I don't know. I never even heard a third shot."

On his return to his office he told Lillian Rogers " to call the police or the Secret Service... I just went to my desk and stopped there until the police came and then we were required to get a place to develop the films. I knew I had something, I figured it might be of some help - I didn't know what." Zapruder's colour film shows the entire assassination sequence and became an important part of the evidence looked at by those investigating the assassination.

By 25th November, 1963, Zapuder's film had been sold to Life Magazine. In charge of the purchase was C. D. Jackson, a close friend of Henry Luce, the owner of the magazine. According to Carl Bernstein, Jackson was "Henry Luce's personal emissary to the CIA". When appearing before the Warren Commission, Zapruder claimed he received $25,000 and then gave this money to the Firemen's and Policemen's Benevolence. However, when the contract was eventually published it showed that Zapruder received $150,000 for the eighteen-second film.