On this day on 25th June

On this day in 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn took place. In 1874 Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer led an expedition to the Black Hills of Dakota. He reported that he discovered gold in the area. The following year the United States government attempted to buy the Black Hills for six million dollars. The area was considered sacred by the Sioux and they refused to sell. Custer's story attracted gold hunters and in April 1876 the mining town of Deadwood was established in the area.

On 17th May Sioux warriors killed and scalped five settlers in the Black Hills. Over the next couple of days seven more cases of men being murdered by the Sioux. On 17th June 1876, General George Crook and about 1,000 troops, supported by 300 Crow and Shoshone, fought against 1,500 members of the Sioux and Cheyenne tribes. The battle at Rosebud Creek lasted for over six hours. This was the first time that Native Americans had united together to fight in such large numbers. On 28th June General William Sherman declared: "Forbearance has ceased to be a virtue toward these Indians, and only a severe and persistent chastisement will bring them to a sense of submission."

On 22nd June, George A. Custer and 655 men were sent out to locate the villages of the Sioux and Cheyenne involved in the battle at Rosebud Creek. A very large encampment was discovered three days later. It was over 15 miles away and even with field glasses Custer was unable to discover the number of warriors the camp contained.

Instead of waiting for the arrival of the rest of the army led by General Alfred Terry, Custer decided to act straight way. He divided his force into three battalions in order to attack the camp from three different directions. One group led by Captain Frederick Benteen was ordered to march to the left. A second group led by Major Marcus Reno was sent to attack the encampment via the Little Big Horn River.

Major Reno was the first to charge the village. When he discovered that the camp was far larger than was expected he retreated to the other side of the Little Big Horn River. He was later joined by Captain Benteen and although they suffered heavy casualties they were able to fight off the attack.

George A. Custer and his men rode north on the east side of the Little Big Horn River. The Sioux and Cheyenne saw Custer's men and swarmed out of the village. Custer was forced to retreat into the bluffs to the east where he was attacked by about 4,000 warriors. At the battle of the Little Bighorn Custer and all his 231 men were killed. This included his two brothers, Tom and Boston, his brother-in-law, James Calhoun, and his nephew, Autie Reed.

The soldiers under Reno and Benteen continued to be attacked and 47 of them were killed before they were rescued by the arrival of General Alfred Terry and his army. It was claimed afterwards that Custer had been killed by his old enemy, Rain in the Face. However, there is no hard evidence to suggest that this is true.

General Philip H. Sheridan concluded that George A. Custer had made several important mistakes at the Little Big Horn. He argued that after their seventy mile journey, Custer's men were too tired to fight effectively. Custer had also made a mistake in developing a plan of attack on the false assumption that the Sioux and Cheyenne would attempt to escape rather than fight the soldiers.

Sheridan also criticized Custer's decision to divide his men into three groups: "Had the Seventh Cavalry been held together, it would have been able to handle the Indians on the Little Big Horn." His final mistake was to attack what was probably the largest group of Native Americans ever assembled on the North American continent. President Ulysses Grant agreed with this assessment and when interviewed by the New York Herald he said: "I regard Custer's Massacre was a sacrifice of troops, brought on by Custer himself, that was wholly unnecessary".

After the battle Captain Frederick Benteen believed that Custer's battalion had taken more than their own number of the enemy with them. Contemporary newspaper accounts claimed that over 200 Sioux warriors had been killed during the attack. But interviews with surviving chiefs, have put the Indian loss at about 45 killed. As Flying Hawk said after the battle: "The white men's accounts are guesswork... for no white man knows. None left."

After the battle false stories circulated that one of Custer's party had survived. On 6th July, 1876, the Bismarck Tribune reported that "one Crow scout hid himself in the field and witnessed and survived the battle." Three days later the New York Times reported that a scout had escaped through the lines by disguising himself in a Sioux blanket."

On 26th July 1876 the New York Herald Tribune published an interview with an Indian scout who it claimed had survived the battle. The newspaper quoted the scout as saying that "General Custer was the last man to be killed." He also added that Custer had not been scalped because the Sioux respected their brave enemy.

Custer's scout Curly was the person most often identified as the lone survivor. He denied this, pointing out that the four Indian scouts (Hairy Moccasin, Goes Ahead and White Man Runs Him) had been sent by Custer away from Little Bighorn before the battle began. However, on 29th July, the Chicago Tribune published an article claiming that Curly had told them that "more Indians were killed than Custer had men." John F. Finerty of the Chicago Times also claimed that Curly had witnessed Custer's death. In a book published several years later, Finerty claimed that "Curley said that Custer remained alive throughout the greater part of the engagement, animating his men to determined resistance, but about an hour before the close of the fight lie received a mortal wound."

Soon afterwards the St. Paul Pioneer-Press and Tribune published another account of a lone survivor. Over the next few years newspapers and magazines published several articles based on interviews with so-called lone survivors such as Williad Carlisle, W. B. Hicks, James Snepp, W. J. Baily, George Yee, John Lockwood, Jim Flannagan, Alexander McDonnell and Charles Mitchel.

In his influential book, The Life of General George A. Custer (1876), Frederick Whittaker included the story of Curly witnessing the battle of Little Bighorn as a fact. Whittaker also claimed that Custer had been killed by Rain in the Face. He also insisted that the disaster had been caused by the cowardice of Captain Frederick Benteen and Major Marcus Reno.

The U.S. army responded to the battle of the Little Bighorn by increasing the number of the soldiers in the area. As a result leaders of the attack such as Sitting Bull and Gall fled to Canada, whereas Crazy Horse and his followers surrendered to General George Crook at the Red Cloud Agency in Nebraska. Crazy Horse was later killed while being held in custody at Fort Robinson.

Charles Marion Russell, Battle of Little Bighorn (1903)

On this day in 1876 George Armstrong Custer is killed. George Custer, the son of a blacksmith, was born in New Rumley, Ohio, on 5th December, 1839. The family was poor and when he was ten Custer was forced to live with his aunt in Monroe. While at school he met his future wife, Elizabeth Bacon, the daughter of a judge. Custer did odd jobs for her family, but was never allowed into the house.

Custer wanted to become a lawyer but his family could not afford the training so he decided to become a soldier instead. He attended the Military Academy at West Point but he was a poor student and when he finally graduated in 1861 he was placed 34th out of a class of 34.

After leaving West Point he joined the staff of General George B. McClellan and during the American Civil War he saw action at Bull Run (August, 1862), Antietam (September, 1862) and Gettysburg (June, 1863). Custer emerged as an outstanding cavalry leader and at the age of 23, was given the rank of brigadier general and took command of the Michigan Brigade.

Custer developed a reputation for flamboyant behaviour. He led his troops into battle wearing a black velvet trimmed with gold lace, a crimson necktie and a white hat. He claimed that he adopted this outfit so that his men "would recognize him on any part of the field".

In August , 1864, Custer joined Major General Philip Sheridan in the final Shenandoah Valley campaign. Sheridan and 40,000 soldiers entered the valley and soon encountered troops led by Jubal Early who had just returned from Washington. After a series of minor defeats the Union Army eventually gained the upper hand. His men now burnt and destroyed anything of value in the area and after defeating Early in another large-scale battle on 19th October, the Union Army took control of the Shenandoah Valley.

Custer was a strong supporter of his own abilities. He said of his performance at Gettysburg: "I challenge the annals of warfare to produce a more brilliant or successful charge of cavalry." He also managed to persuade journalists to share this view. After Custer took part in the Shenandoah Valley campaign E. A. Paul of the New York Times reported that "Custer, young as he is, displayed judgment worthy of a Napoleon."

On 1st April, Philip Sheridan, William Sherman and Custer attacked at Five Forks. The Confederates, led by Major General George Pickett, were overwhelmed and lost 5,200 men. On hearing the news, Robert E. Lee decided to abandon Richmond and President Jefferson Davis, his family and government officials, was forced to flee from the city.

By the end of the war Custer had been breveted for gallant and meritorious services on five occasions. Although only wounded once he had 11 horses killed under him.

In January 1866, his commission as major-general expired and he reverted to his 1862 rank of captain in the Regular Army. However, in July, 1866, he was commissioned lieutenant colonel (he was also given the honorary rank of major general) and made second in command of the newly created Seventh Cavalry. He was posted to Fort Riley in Kansas and spent the winter of 1866-67 preparing his troops to take part in the Indian Wars.

Custer's behaviour continued to be erratic. In July 1867 fifteen of his men deserted during a forced march along the Republican River. Custer ordered a search party "to shoot the supposed deserters down dead, and to bring none in alive." Soon afterwards he deserted his command in order to spend a day with his wife. As a result of this actions he was arrested and charged with disobeying orders, deserting his command, failing to pursue Indians who had attacked his escort and ordering his officers to shoot down deserters. Found guilty he was suspended for a year without pay.

General Philip H. Sheridan recalled Custer to duty and on 27th November, 1868, Custer destroyed the Cheyenne village of Chief Black Kettle on the banks of the Washita River. Custer later claimed that his men killed 103 warriors. However, the majority of the victims were women and children. This action was highly controversial as the Cheyenne were not at war against the Americans at this time. General Harney pointed out: "I have worn the uniform of my country 55 years, and I know that Black Kettle was as good a friend of the United States as I am."

One of his own men, Captain Frederick Benteen, also criticized Custer's behaviour during this operation. He was mainly concerned with what happened to Major Joel Elliott and 18 of his men who had been sent off to pursue fleeing members of the Cheyenne tribe. They had been cut off and massacred by warriors from neighbouring villages. Benteen accused Custer of abandoning these men and had been responsible for their deaths. General Philip H. Sheridan rejected these claims and complimented Custer on his "efficient and gallant services" during the attack.

In August 1873, Custer was involved in protecting a group of railroad surveyors. The group were attacked by a Sioux war party near the mouth of Tongue River. During the raid two of the surveyors were killed. Later, Charley Reynolds, an Indian scout, told Custer that Rain in the Face had led the attack at Tongue River. Rain in the Face was living on the Standing Rock Reservation at the time and so Custer had him arrested. Custer forced Rain in the Face to confess but before he could appear in court he managed to escape.

In 1873 Custer was a member of General David Stanley's Yellowstone expedition. Later that year he took command of Fort Abraham Lincoln on the River Missouri. In 1874 Custer led an expedition into the Black Hills of Dakota. Later he published an autobiography, My Life on the Plains (1874).

Custer was called to Washington in March, 1876, to testify before a Congressional committee probing frauds in the Indian Service. President Ulysses Grant was furious when Custer's evidence damaged the reputation of his former War Secretary, William Belknap. Grant was so angry he deprived Custer of his command. However, after protests from senior officers in the army, Grant backed down and Custer was able to return as commander of the 7th Cavalry.

At this time the Sioux and Cheyenne were attempting to resist the advance of white migration. On 17th June 1876 General George Crook and about 1,000 troops, supported by 300 Crow and Shoshone, fought against 1,500 members of the Sioux and Cheyenne tribes. The battle at Rosebud Creek lasted for over six hours. This was the first time that Native Americans had united together to fight in such large numbers.

On 22nd June, Custer and 655 men were sent out to locate the villages of the Sioux and Cheyenne involved in the battle at Rosebud Creek. A very large encampment was discovered three days later. It was over 15 miles away and even with field glasses Custer was unable to discover the number of warriors the camp contained.

Instead of waiting for the arrival of the rest of the army led by General Alfred Terry, Custer decided to act straight way. He divided his force into three battalions in order to attack the camp from three different directions. One group led by Captain Frederick Benteen was ordered to march to the left. A second group led by Major Marcus Reno was sent to attack the encampment via the Little Big Horn River.

Major Reno was the first to charge the village. When he discovered that the camp was far larger than was expected he retreated to the other side of the Little Big Horn River. He was later joined by Captain Benteen and although they suffered heavy casualties they were able to fight off the attack.

Custer and his men rode north on the east side of the Little Big Horn River. The Sioux and Cheyenne saw Custer's men and swarmed out of the village. Custer was forced to retreat into the bluffs to the east where he was attacked by about 4,000 warriors. At the battle of the Little Bighorn Custer and all his 231 men were killed. This included his two brothers, Tom and Boston, his brother-in-law, James Calhoun, and his nephew, Autie Reed.

The soldiers under Reno and Benteen continued to be attacked and 47 of them were killed before they were rescued by the arrival of General Alfred Terry and his army. It was claimed afterwards that Custer had been killed by his old enemy, Rain in the Face. However, there is no hard evidence to suggest that this is true.

General Philip H. Sheridan concluded that George A. Custer had made several important mistakes at the Little Big Horn. He argued that after their seventy mile journey, Custer's men were too tired to fight effectively. Custer had also made a mistake in developing a plan of attack on the false assumption that the Sioux and Cheyenne would attempt to escape rather than fight the soldiers.

Sheridan also criticized Custer's decision to divide his men into three groups: "Had the Seventh Cavalry been held together, it would have been able to handle the Indians on the Little Big Horn." His final mistake was to attack what was probably the largest group of Native Americans ever assembled on the North American continent. President Ulysses Grant agreed with this assessment and when interviewed by the New York Herald he said: "I regard Custer's Massacre was a sacrifice of troops, brought on by Custer himself, that was wholly unnecessary". Despite this criticism George Custer was given a hero's burial at West Point.

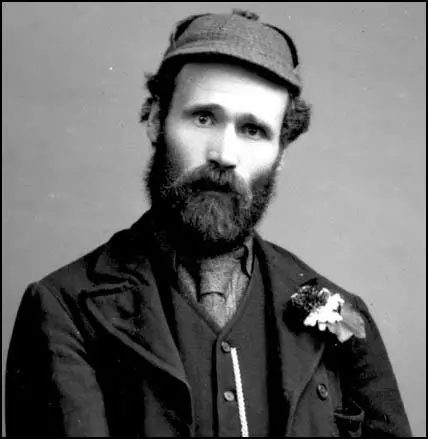

George Armstrong Custer

On this day in 1894 Keir Hardie makes speech on the royal family in the House of Commons. On Saturday, 23rd June, 1894, there was a massive explosion in a colliery near Pontypridd, Wales. Two days later, Hardie suggested in the House of Commons that a message of condolence to the relatives of the 251 coal miners that had been killed in the accident, should be added to an address of congratulations on the birth of a royal heir (the future Edward VIII). When the request was refused, Hardie made a speech attacking the privileges of the monarchy.

J. R. Clynes later commented: "The House rose at him like a pack of wild dogs. His voice was drowned in a din of insults and the drumming of feet on the floor. But he stood there, white-faced, blazing-eyed, his lips moving, though the words were swept away." Later, Hardie wrote: "The life of one Welsh miners of greater commercial and moral value to the British nation than the whole Royal crowd put together."

On this day in 1896 Margaret Gladstone writes a letter to Ramsay MacDonald. "It is only just beginning to dawn on me a very little bit, since your last Sunday's letter, what a new good gift I have in your love... But when I think how lonely you have been I want with all my heart to make up to you one tiny little bit for that. I have been lonely too - I have envied the veriest drunken tramps I have seen dragging about the streets if they were man and woman because they had each other... This is truly a love letter: I don't know when I shall show it you: it may be that I never shall. But I shall never forget that I have had the blessing of writing it."

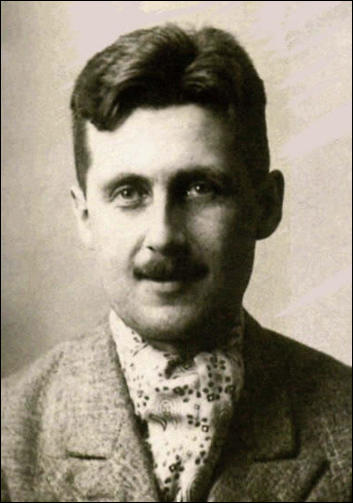

On this day in 1903, Eric Blair (George Orwell), the only son of Richard Walmesley Blair, and his wife, Ida Mabel Limouzin, was born in Bengal, India. His sister, Marjorie, had been born in 1898. His father was a sub-deputy agent in the Opium Department of the Indian Civil Service.

In the summer of 1907, Mabel Blair brought her son and daughter home to England and set up home in Henley-on-Thames. A third child, Avril, was born in 1908. In September, 1911, Orwell was sent to St Cyprian's, a private preparatory school at Eastbourne.

He later recalled: "I barely saw my father before I was eight. For this and other reasons I was somewhat lonely, and I soon developed disagreeable mannerisms which made me unpopular throughout my schooldays... I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued. I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life."

In 1917 Orwell entered Eton College. Over the next four years he wrote satirical verses and short stories for various college magazines. He disapproved of his public school education and many years later he wrote: "Whatever may happen to the great public schools when our educational system is reorganised, it is almost impossible that Eton should survive in anything like its present form, because the training it offers was originally intended for a landowning aristocracy and had become an anachronism... The top hats and tail coats, the pack of beagles, the many-coloured blazers, the desks still notched with the names of Prime Ministers had charm and function so long as they represented the kind of elegance that everyone looked up to."

When he left Eton in 1921 he did not go to university and instead joined the Indian Imperial Police in Burma. He hated the experience and during this period he became a socialist and an anti-imperialist: "This increased my natural hatred of authority and made me for the first time fully aware of the existence of the working classes, and the job in Burma had given me some understanding of the nature of imperialism."

In the autumn of 1927 George Orwell began living in a cheap room in Portobello Road, Notting Hill. He spent a great deal of his time in the East End of London in his quest to get to know the poor and exploited. In the spring of 1928 he moved to a working-class district of Paris. For about ten weeks in the late autumn of 1929 he worked as a dishwasher and kitchen porter in a luxury hotel and a restaurant in the city.

On his return to London he became friends with Kingsley Martin, John Middleton Murry and Richard Rees , who helped him to get articles and reviews published in journals such as the New Statesman, New English Weekly and The Adelphi. Orwell also became friends with the left-wing publisher, Victor Gollancz, and in 1933 he published Down and Out in Paris and London.

George Orwell wrote in the introduction to the book: "I have given the impression that I think Paris and London are unpleasant cities. This was never my intention and if, at first sight, the reader should get this impression this is simply because the subject-matter of my book is essentially unattractive: my theme is poverty. When you haven't a penny in your pocket you are forced to see any city or country in its least favourable light and all human beings, or nearly all, appear to you either as fellow sufferers or as enemies."

However, Gollancz came under attack from some of his Jewish customers. S. M. Lipsey wrote: "As a Jew it is to me inexplicable that one of the most eminent and honourable names in Anglo-Jewry should bear the imprimatur of a publication wherein are references to Jews of a most contemptible and repugnant character. I feel bound to enter a very earnest and emphatic protest." Gollancz replied: "I detest all forms of patriotism, which has made, and is making, the world a hell: and of all forms of patriotism, Jewish patriotism seems to me the most detestable. If Down and Out in London and Paris has given a jar to your Jewish complacency, I have one additional reason to be pleased for having published it."

Over the next few years he published three novels, Burmese Days (1934), A Clergyman's Daughter (1935) and Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936). The books did not sell well and Orwell was unable to make enough money to become a full-time writer and had to work as a teacher and as an assistant in a bookshop.

Orwell had been shocked and dismayed by the persecution of socialists in Nazi Germany. Like most socialists, he had been impressed by the way that the Soviet Union had been unaffected by the Great Depression and did not suffer the unemployment that was being endured by the workers under capitalism. However, Orwell was a great believer in democracy and rejected the type of government imposed by Joseph Stalin.

Orwell decided he would now become a political writer "In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer... Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows."

Orwell was commissioned by Victor Gollancz to produce a documentary account of unemployment in the north of England for his Left Book Club. In February, 1936, Orwell wrote to Richard Rees about his research for the book that was eventually published as the The Road to Wigan Pier. "I have only been down one coal mine so far but hope to go down some more in Yorkshire. It was for me a pretty devastating experience and it is fearful thought that the labour of crawling as far as the coal face (about a mile in this case but as much as 3 miles in some mines), which was enough to put my legs out of action for four days, is only the beginning and ending of a miner's day's work, and his real work comes in between."

The Spanish Civil War began on 18th July, 1936. Despite only being married for a month he immediately decided to go and support the Popular Front government against the fascist forces led by General Francisco Franco. He contacted John Strachey who took him to see Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Orwell later recalled: "Pollitt after questioning me, evidently decided that I was politically unreliable and refused to help me, evidently decided that I was politically unreliable and refused to help me, also tried to frighten me out of going by talking a lot about Anarchist terrorism."

Orwell visited the headquarters of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and obtained letters of recommendation from Fenner Brockway and Henry Noel Brailsford. Orwell arrived in Barcelona in December 1936 and went to see John McNair, to run the ILP's political office. The ILP was affiliated with Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), an anti-Stalinist organisation formed by Andres Nin and Joaquin Maurin. As a result of an ILP fundraising campaign in England, the POUM had received almost £10,000, as well as an ambulance and a planeload of medical supplies.

It has been pointed out by D. J. Taylor, that McNair was "initially wary of the tall ex-public school boy with the drawling upper-class accent". McNair later recalled: "At first his accent repelled my Tyneside prejudices... He handed me his two letters, one from Fenner Brockway, the other from H.N. Brailsford, both personal friends of mine. I realised that my visitor was none other than George Orwell, two of whose books I had read and greatly admired." Orwell told McNair: "I have come to Spain to join the militia to fight against Fascism". Orwell told him that he was also interested in writing about the "situation and endeavour to stir working-class opinion in Britain and France." Orwell talked about producing a couple of articles for The New Statesman.

McNair went to see Orwell at the Lenin Barracks a few days later: "Gone was the drawling ex-Etonian, in his place was an ardent young man of action in complete control of the situation... George was forcing about fifty young, enthusiastic but undisciplined Catalonians to learn the rudiments of military drill. He made them run and jump, taught them to form threes, showed them how to use the only rifle available, an old Mauser, by taking it to pieces and explaining it."

In January 1937 George Orwell, given the rank of corporal, was sent to join the offensive at Aragón. The following month he was moved to Huesca. Orwell wrote to Victor Gollancz about life in Spain. "Owing partly to an accident I joined the POUM miltia instead of the International Brigade which was a pity in one way because it meant that I have never seen the Madrid front; on the other hand it has brought me into contact with Spaniards rather than Englishmen and especially with genuine revolutionaries. I hope I shall get a chance to write the truth about what I have seen."

A report appeared in a British newspaper of Orwell leading soldiers into battle: "A Spanish comrade rose and rushed forward. Charge! shouted Blair (Orwell)... In front of the parapet was Eric Blair's tall figure cooly strolling forward through the storm of fire. He leapt at the parapet, then stumbled. Hell, had they got him? No, he was over, closely followed by Gross of Hammersmith, Frankfort of Hackney and Bob Smillie, with the others right after them. The trench had been hastily evacuated... In a corner of a trench was one dead man; in a dugout was another body."

On 10th May, 1937, Orwell was wounded by a Fascist sniper. He told Cyril Connolly "a bullet through the throat which of course ought to have killed me but has merely given me nervous pains in the right arm and robbed me of most of my voice." He added that while in Spain "I have seen wonderful things and at last really believe in Socialism, which I never did before."

Joseph Stalin appointed Alexander Orlov as the Soviet Politburo adviser to the Popular Front government. Orlov and his NKVD agents had the unofficial task of eliminating the supporters of Leon Trotsky fighting for the Republican Army and the International Brigades. This included the arrest and execution of leaders of POUM, National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI). Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996) has pointed out: "Stalin had a secret and extremely important aim in Spain: to eliminate the supporters of Trotsky who had gathered from all over the world to fight for the Spanish revolution. NKVD men, and Comintern agents loyal to Stalin, accused the Trotskyists of espionage and ruthlessly executed them."

As Orwell had been fighting with POUM he was identified as an anti-Stalinist and the NKVD attempted to arrest him. Orwell was now in danger of being murdered by communists in the Republican Army. With the help of the British Consul in Barcelona, George Orwell, John McNair and Stafford Cottman were able to escape to France on 23rd June.

Many of Orwell's fellow comrades were not so lucky and were captured and executed. When he arrived back in England he was determined to expose the crimes of Stalin in Spain. However, his left-wing friends in the media, rejected his articles, as they argued it would split and therefore weaken the resistance to fascism in Europe. Orwell was particularly upset by his old friend, Kingsley Martin, the editor of the country's leading socialist journal, The New Statesman, for refusing to publish details of the killing of the anarchists and socialists by the communists in Spain.

Left-wing and liberal newspapers such as the Manchester Guardian, News Chronicle and the Daily Worker, as well as the right-wing Daily Mail and The Times, joined in the cover-up. Orwell did managed to persuade the New English Weekly to publish an article on the reporting of the Spanish Civil War. "I honestly doubt, in spite of all those hecatombs of nuns who have been raped and crucified before the eyes of Daily Mail reporters, whether it is the pro-Fascist newspapers that have done the most harm. It is the left-wing papers, the News Chronicle and the Daily Worker, with their far subtler methods of distortion, that have prevented the British public from grasping the real nature of the struggle."

In another article in the magazine he explained how in "Spain... and to some extent in England, anyone professing revolutionary Socialism (i.e. professing the things the Communist Party professed until a few years ago) is under suspicion of being a Trotskyist in the pay of Franco or Hitler... in England, in spite of the intense interest the Spanish war has aroused, there are very few people who have heard of the enormous struggle that is going on behind the Government lines. Of course, this is no accident. There has been a quite deliberate conspiracy to prevent the Spanish situation from being understood."

George Orwell wrote about his experiences of the Spanish Civil War in Homage to Catalonia. The book was rejected by Victor Gollancz because of its attacks on Joseph Stalin. During this period Gollancz was accused of being under the control of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). He later admitted that he had come under pressure from the CPGB not to publish certain books in the Left Book Club: "When I got letter after letter to this effect, I had to sit down and deny that I had withdrawn the book because I had been asked to do so by the CP - I had to concoct a cock and bull story... I hated and loathed doing this: I am made in such a way that this kind of falsehood destroys something inside me."

The book was eventually published by Frederick Warburg, who was known to be both anti-fascist and anti-communist, which put him at loggerheads with many intellectuals of the time. The book was attacked by both the left and right-wing press. Although one of the best books ever written about war, it sold only 1,500 copies during the next twelve years. As Bernard Crick has pointed out: "Its literary merits were hardly noticed... Some now think of it as Orwell's finest achievement, and nearly all critics see it as his great stylistic breakthrough: he became the serious writer with the terse, easy, vivid colloquial style."

Orwell was also appalled by the way the left-wing press had reported the trial of Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev. It was claimed that they had plotted and carried out the assassination of Sergey Kirov and planned the overthrow of Joseph Stalin and his leading associates - all under the direct instructions of Leon Trotsky. They were also accused of conspiring with Adolf Hitler against the Soviet Union. The Observer reported: "It is futile to think the trial was staged and the charges trumped up. The government's case against the defendants (Zinoviev and Kamenev) is genuine." The New Statesman agreed that "very likely there was a plot" by the accused against Stalin.

Orwell complained that the Daily Herald and the Manchester Guardian went along with this idea that there was this world-wide "Trotsky-Fascist" plot. He estimated that there were 3,000 political prisoners in Spanish prisons who were accused of being involved in this preposterous plot, but this was not being reported in the media. "The result was that there was no protest from abroad and all these thousands of people have stayed in prison, and a number have been murdered, the effect being to spread hatred and dissension all through the Socialist movement."

In 1938 Orwell was an isolated figure on the left. He rejected the policies of the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Labour Party. This was partly over the issue of Spain but saw Clement Attlee as a leader of a party that would probably "fling every principle overboard" in order to get power. He therefore joined the very small Independent Labour Party: "It is vitally necessary that there should be in existence some body of people who can be depended on, even in the face of persecution, not to compromise their Socialist principles."

Orwell also supported rearmament in order to take on Adolf Hitler in the fight against fascism. In a range of different issues, from anti-communism and his opposition to appeasement, he found himself in the same camp as Winston Churchill and other right-wing political figures in the Conservative Party. The vast majority of those on the left in Britain were sympathetic to the Soviet Union and were willing to do whatever was needed to avoid a war with Nazi Germany.

He found it embarrassing but as he pointed out in an article written in July 1938, why those on the right were willing to do deals with Stalin in order to combat Hitler. The main reason was that the "Fascist powers menace the British Empire". He goes onto argue that the function of the "Conservative anti-Fascists... is to be the liaison officers. The average English left-winger is now a good imperialist." The Spanish Civil War and the rise of fascism in Europe "has had a catalytic effect upon English opinion, bringing into being combinations which no one could have foreseen a few years ago".

George Orwell decided that he was not going to be put off by his unpleasant bed-fellows. He believed the best defence against fascism was democracy. But he feared that the British people, like those in Germany, Italy, Portugal and Spain, would be persuaded to give up their democratic rights in order to be led by dictators. "The radio, press-censorship, standardized education and the secret police have altered everything. Mass-suggestion is a science of the last twenty years, and we do not yet know how successful it will be."

In 1939 Clarence Streit published a book called Union Now: A Proposal for a Federal Union. He suggested that the 15 major countries that had democratic institutions should join together to form "a common government, common money and complete internal free trade". Other countries would be admitted to the Union when and if they "proved themselves worthy". Streit goes on to argue that the combined strength would be so great as to make any military attack on them hopeless. Orwell, agreed that Streit was probably right about the protection such a system would give Britain in the short-term but totally rejected the idea of a "political and economic union". He disliked the idea of being ruled by an un elected bureaucracy that in "essence" was a "mechanism for exploiting cheap labour - under the heading of democracies!" Orwell ends the review by stating that the best defence people have in a capitalist world is the democratic form of government.

Orwell published Coming up for Air in 1939. In August 1941 Orwell began work for the Eastern Service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). His main task was to write the scripts for a weekly news commentary on the Second World War. Orwell's scripts were broadcast to the people of India between the end of 1941 and early 1943. During this period Orwell also worked for the Observer newspaper.

In 1943 Aneurin Bevan, the editor of the socialist journal Tribune, recruited George Orwell to write a weekly column, As I Please. Orwell's plain, lucid style, made him highly effective as a campaigning journalist and some of his best writing was done during this period.

In a famous article in The Evening Standard he argued: "The Home Guard could only exist in a country where men feel themselves free. The totalitarian states can do great things, but there is one thing they cannot do: they cannot give the factory-worker a rifle and tell him to take it home and keep it in his bedroom."

George Orwel's next book, Animal Farm, was a satire in fable form of the communist revolution in Russia. The book, heavily influenced by his experiences of the way communists behaved during the Spanish Civil War, upset many of his left-wing friends and his former publisher, Victor Gollancz, rejected it. Published in 1945, the novel became one of Britain's most popular books.

His friend, A. J. Ayer, pointed out: "Though he held no religious belief, there was something of a religious element in George's socialism. It owed nothing to Marxist theory and much to the tradition of English Nonconformity. He saw it primarily as an instrument of justice. What he hated in contemporary politics, almost as much as the abuse of power, was the dishonesty and cynicism which allowed its evils to be veiled. When I first got to know him, he had written but not yet published Animal Farm, and while he believed that the book was good he did not foresee its great success. He was to be rather dismayed by the pleasure that it gave to the enemies of any form of socialism, but with the defeat of fascism in Germany and Italy he saw the Russian model of dictatorship as the most serious threat to the realization of his hopes for a better world."

Orwell's final book was influenced by his failing health and his disillusionment with a Labour government that had been elected with a large majority in the 1945 General Election but made little attempt to introduce the kind of socialism that he believed in.

In 1945 George Orwell reviewed the anti-Utopian novel We by Yevgeni Zamyatin for Tribune. The book inspired his novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four. Published in 1949, the book was a pessimistic satire about the threat of political tyranny in the future. The novel had a tremendous impact and many of the new words and phrases used in the book passed into everyday language.

George Orwell died of tuberculosis on 21st January, 1950.

On this day in 1909, Marion Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and sent to prison and starts the first hunger strike. During the summer of 1908 the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) introduced the tactic of breaking the windows of government buildings. On 30th June suffragettes marched into Downing Street and began throwing small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house. As a result of this demonstration, twenty-seven women were arrested and sent to Holloway Prison. The following month Wallace-Dunlop was arrested and charged with "obstruction" and was briefly imprisoned.

While in prison she came into contact with two women who had been found guilty of killing children. She wrote in her diary: "It made me feel frantic to realize how terrible is a social system where life is so hard for the girls that they have to sell themselves or starve. Then when they become mothers the child is not only a terrible added burden, but their very motherhood bids them to kill it and save it from a life of starvation, neglect. I begin to feel I must be dreaming that this prison life can’t be real. That it is impossible that it is true and I am in the midst of it. I know now the meaning of the screened galley in the Chapel, the poor condemned girl sits there with a wardress."

On her release she made a speech about the plight of the working-class: "In this country every year 120,000 babies die before they are a year old, and most of these die because of the conditions into which they are born. It is not so much the babies who die that one pities but those who survive, poor, maimed, starved, stunted little beings."

On 25th June 1909 Wallace-Dunlop was charged "with wilfully damaging the stone work of St. Stephen's Hall, House of Commons, by stamping it with an indelible rubber stamp, doing damage to the value of 10s." According to a report in The Times Wallace-Dunlop printed a notice that read: "Women's Deputation. June 29. Bill of Rights. It is the right of the subjects to petition the King, and all commitments and prosecutions for such petitionings are illegal."

Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. On 5th July, 1909 she petitioned the governor of Holloway Prison: “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.”

In her book, Unshackled (1959) Christabel Pankhurst claimed: "Miss Wallace Dunlop, taking counsel with no one and acting entirely on her own initiative, sent to the Home Secretary, Mr. Gladstone, as soon as she entered Holloway Prison, an application to be placed in the first division as befitted one charged with a political offence. She announced that she would eat no food until this right was conceded."

Frederick Pethick-Lawrence wrote to Wallace-Dunlop: "Nothing has moved me so much - stirred me to the depths of my being - as your heroic action. The power of the human spirit is to me the most sublime thing in life - that compared with which all ordinary things sink into insignificance." He also congratulated her for "finding a new way of insisting upon the proper status of political prisoners, and of the resourcefulness and energy in the face of difficulties that marked the true Suffragette."

Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her after fasting for 91 hours. As Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), has pointed out: "As with all the weapons employed by the WSPU, its first use sprang directly from the decision of a sole protagonist; there was never any suggestion that the hunger strike was used on this first occasion by direction from Clement's Inn."

Soon afterwards other imprisoned suffragettes adopted the same strategy. Unwilling to release all the imprisoned suffragettes, the prison authorities force-fed these women on hunger strike. In one eighteen month period, Emily Pankhurst, who was now in her fifties, endured ten of these hunger-strikes.

On this day in 1961 Mary Blathwayt died. Mary Blathwayt, the daughter of Colonel Linley Blathwayt, a retired army officer, and Emily Blathwayt, was born in 1879. Her father was an officer in the British Indian Army and served in India for many years. Blathwayt retired from the army and in 1882 he purchased Eagle House near Batheaston, a large house set in four acres of land.

Linley Blathwayt was a supporter of the Liberal Party. Mary and her mother also held progressive political views and were both advocates of women's suffrage. Mary and her mother devoted much of their time to teaching music to village children.

According to B. M. Willmott Dobbie, the author of A Nest of Suffragettes in Somerset (1979): "Mary led the sheltered life of an upper middle-class daughter at home, paying and receiving calls, helping with charitable events in the village, working in the garden and tending her hens, for whom she had an especial fondness, taking an active part in the Avon Vale Musical Society, giving violin lessons to village boys, who invariably disappointed her.... There were cycle rides with girl friends, and tours with her brother William, whom they always stayed in Temperance Hotels."

In July 1906 she sent a donation of 3 shillings to Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Her mother and father also supported the Women's Suffrage bill being discussed in the House of Commons. In March 1907 Emily Blathwayt wrote: "Women's Suffrage bill brought in by private member and government allowed it to be talked out. The Liberals do not keep their pledges. The Women's Union beg all to turn against Liberals and think only of the one Cause. Linley is much in favour of women having the vote, he thinks they would do much more good than harm."

Mary became friends with Lilias Ashworth Hallett, who was a member of the NUWSS and the WSPU. In March 1908 she was introduced to Millicent Fawcett. In her diary she wrote: "This afternoon I went into Bath by tram and then walked to Claverton Lodge... Mrs. Ashworth Hallett introduced me first to Miss Clark, and then to Mrs. Fawcett. Then others came in: Dr. Mary Morris... We all had tea there and stayed talking till 6.30. I have never been to the house before; it is a beautiful place. Mrs. Hallett is most kind. I could not believe I was looking at Mrs. Fawcett, she looks so young. I believe she has been working for Votes for Women for 40 years."

Mary Blathwayt first met Annie Kenney at a WSPU meeting in Bath. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), claims that Blathwayt had fallen "under her spell and gave her a rose". Soon afterwards Kenney introduced her to Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Christabel Pankhurst. She now became an active member and over the next few weeks she began distributing WSPU leaflets in the area.

In May 1908 Mary agreed to help Annie Kenney, Elsie Howey, Clara Codd and Mary Phillips to organise the women's suffrage campaign in her area. She wrote in her diary: "This afternoon I helped Annie Kenney make her plans for a West of England campaign, I wrote out lists of towns and dates which are to be sent to Mrs. Pankhurst and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence. This evening Miss Howey went round the town with some steps, and I went with her. And when we came to a crowd she got onto the steps and shouted Keep the Liberal out. Votes for Women". Mary also a public meeting that was addressed by Gladice Keevil. She recorded in her diary: "She and I held an open air meeting at the Wharf. I took the chair, the first time I have ever done such a thing. I read out a few words of introduction, announced a meeting for tomorrow and called upon Miss Keevil to speak."

By December of that year Mary Blathwayt was elected to the executive committee of the local branch of the WSPU. Blathwayt became very friendly with Annie Kenney. The two women spent much of 1908 and 1909 speaking "from dogcarts at open-air meetings, chalked pavements and sold pamphlets." However, she refused to become involved in any activity that might risk her being arrested. In July 1909 she refused a written request from Emmeline Pankhurst to join a deputation "which carried with it the virtual certainty of a prison sentence." The reason that she gave was that "father would not like it". She also noted in her diary that "Annie Kenney does not wish me to go."

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence wrote an article in Votes for Women in February 1909, they acknowledged the help given by the Blathwayt family to the cause of women's suffrage: "I say to you young women who have private means or whose parents are able and willing to support you while they give you freedom to choose your vocation. Come and give one year of your life to bringing the message of deliverance to thousands of your sisters... Put yourself through a short course of training under one of our chief officers or at headquarters in London, and then become one of our honorary staff organisers. Miss Annie Kenney, in the West of England, has two such honorary organisers. Miss Blathwayt is the only daughter of Colonel Lindley Blathwayt, of Bath. Yet her parents have set her free with their fullest approbation and sympathy, and with a generous allowance, to devote her whole time to the work."

On 8th June, 1909, Mary recorded in her diary how she and Elsie Howey were attacked during one public meeting in Bristol. "We were on a lorry and a large crowd of children were waiting for us when we arrived. Things were thrown at us all the time; but when we drove away at the end we were hit a great many times. Elsie Howey had her lip hit and it bled. I was hit by potatoes, stones, turf and dust. Something hit me very hard on my right ear as I was getting into our tram. Someone threw a big stone as big as a baby's head; it fell onto the lorry."

Elizabeth Crawford claims Annie Kenney spent a lot of time at Mary Blathwayt's home, Eagle House near Batheaston "where, for the first time, she began to learn French, to play tennis, to swim, to ride and to drive." A fellow member of the WSPU, Teresa Billington-Greig claimed that Kenney was "emotionally possessed" by Christabel Pankhurst during this period. However, Mary argued that it was Kenney who was the dominating personality as she had a "wonderful influence over people".

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued that Annie Kenney had a series of romantic attachments with other suffragettes: "The relationship (with Christabel Pankhurst) would be mirrored, though never matched in its intensity, by a number of later relationships between Annie and other suffragettes. The extent of their physical nature has never been revealed, but it is certain that in some sense these were romantic attachments. One historian who argues that Annie must have had sexual feelings for other women adds that lesbianism was barely recognised at the time. Such relationships, even when they involved sharing beds, excited little comment. Already, Christabel had formed a close friendship with Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, suffrage campaigners who lived together in Manchester. Her relationship with Eva, in particular, had become intense enough to excite a great deal of comment from her family - according to Sylvia."

Colonel Linley Blathwayt was sympathetic to the WSPU cause and he built a summer-house in the grounds of the estate that was called the "Suffragette Rest". Members of the WSPU who endured hunger strikes went to stay at Eagle House and the summer-house. Mary Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney had intimate relationships with at least ten members of the WSPU at Batheaston. Blathwayt records in her diary that she slept with Annie in July 1908. Soon afterwards she illustrated jealousy with the comments that "Miss Browne is sleeping in Annie's room now." The diary suggests that Annie was sexually involved with both Christabel Pankhurst and Clara Codd. Blathwayt wrote on 7th September 1910 that "Miss Codd has come to stay, she is sleeping with Annie." Codd's autobiography, So Rich a Life (1951) confirms this account.

The historian, Martin Pugh, points out that "Mary writes matter-of-fact lines such as, Annie slept with someone else again last night, or There was someone else in Annie's bed this morning. But it is all done with no moral opprobrium for the act itself. In the diary Kenney appears frequently and with different women. Almost day by day Mary says she is sleeping with someone else."

Colonel Linley Blathwayt decided to create a suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. The idea was for women to be invited to plant a tree to commemorate their prison sentences and hunger strikes. On 23rd April 1909 Emily Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Constance Lytton and Clara Codd all planted trees. "Beautiful day for the tree planting and Linley photographed the three in a group at each tree. Annie put the West one, Mrs. P. Lawrence, South, and Lady Constance the East. Miss Codd came to the field."

Over the next few months Emmeline Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Mary Phillips, Vera Holme, Jessie Kenney, Georgina Brackenbury, Marie Brackenbury, Aeta Lamb, Theresa Garnett, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Adela Pankhurst, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Vera Wentworth and Elsie Howey also took part in this ceremony. After the visit of Christabel Pankhurst Emily Blathwayt wrote in her diary: "Christabel has planted her cedar of Lebanon by the pond; it was raining all the time. There is a wonderful charm about Christabel; she looks sweet and not like her photo. She is quiet and retiring." Eventually, even women who had not been to prison, such as Millicent Fawcett and Lilias Ashworth Hallett planted trees.

Jessie Kenney developed a "lung condition" also spent time recovering at Eagle House in 1910. Others who visited during this period included Constance Lytton, Elsie Howey, Mary Phillips, Charlotte Despard, Mary Allen, Charlotte Marsh, Lilias Ashworth Hallett, Aeta Lamb, Georgina Brackenbury, Marie Brackenbury, Marie Naylor, Laura Ainsworth, Margaret Haig Thomas, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Theresa Garnett, Gladice Keevil, Maud Joachim, Vida Goldstein, Minnie Baldock, Vera Wentworth, Clare Mordan and Helen Watts. Colonel Blathwayt photographed the women. These were then signed and sold at WSPU bazaars.

In April 1911 Mary Blathwayt took part in the campaign to undermine the national census. She wrote in her diary: "I went into Bath last night by tram and walked to 12 Lansdown Crescent (an empty house rented for the purpose by Mrs. Mansel) to spend the night there and so evade the census, as a protest against the Government for not giving us Votes for Women. I got there before 10 o'clock. A little crowd of people were standing in the next doorway on the east side to watch us go in. I took a nightdress etc. with me and had a room to myself on the 1st floor and a bed. Everyone else slept on mattresses. We had a charming room to hold our meeting, beautifully decorated and very comfortable. There were 29 of us... We sat up until 2 a.m. this morning."

Annie Kenney wrote in her memoirs, Memories of a Militant (1924) about the help that the Blathwayt family gave her during the campaign: "It would be futile to mention other names, they were all wonderful to me. There is just one I should like to mention, that of the late Colonel Blathwayt. He and Mrs. Blathwayt, of Eagle House, Batheaston treated me as though I were one of their own family. All my week-ends I spent under their hospitable roof."

In November 1912 Emily Blathwayt recorded in her diary that she was unhappy about her daughter's participation in the WSPU. "Mary in Bath all day working for the Pankhurst cause - we wish she was not, but the young people all do this kind of thing now and I suppose it is evolution. The oldest supporters are fast leaving the WSPU, especially those old in years, but people like Miss Lamb do not at all like Mrs. Pankhurst's present policy."

The summer of 1913 saw a further escalation of WSPU violence when they began an arson campaign. In July attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. This was followed by cricket pavilions, racecourse stands and golf clubhouses being set on fire. In June 1913 a house had been burned down close to Eagle House. Under pressure from her parents, Mary Blathwayt resigned from the WSPU.

In her diary she wrote: "I have written to Grace Tollemache (secretary for Bath) and to the secretary of the Women's Social and Political Union to say that I want to give up being a member of the W.S.P.U. and not giving any reason. Her mother, Emily Blathwayt, wrote in her diary: "I am glad to say Mary is writing to resign membership with the W.S.P.U. Now they have begun burning houses in the neighbourhood I feel more than ever ashamed to be connected with them."

Emily and Mary remained active member of the NUWSS. Emily wrote in her diary on 7th February, 1918: "The Reform Bill passed yesterday... Women cannot vote before the age of 30. Wives of men entitled to elect can vote as well as women in their own right and university women also have the franchise... Linley and I walked through the trees this afternoon and wondered how quietly this had come at last, but the war occupies all our thoughts."

Mary Blathwayt continued to live in Batheaston until her death in 1961. Eagle House was sold soon afterwards. B. M. Willmott Dobbie, the author of A Nest of Suffragettes in Somerset (1979), has pointed out: "The land was sold for building. Bulldozers tore down the suffragette trees, and blithely smashed many of the plaques. A number were rescued, however, and are in the museum of the Batheaston Society."