Indian Reservations

An Indian reservation was an area of land reserved for Indian use. The first political leader to suggest this policy was Andrew Jackson. In the 1820s the Cherokees adopted a written constitution that proclaimed that the Cherokee nation had complete jurisdiction over its own territory. The state of Georgia responded by making it illegal for a Native American to bring a legal action against a white man.

The Seminole tribe had disputes with settlers in Florida. The Creeks were involved in several battles with the federal army in Alabama and Georgia. The Chickisaw and Choctaw tribes also had land disputes with emigrants who had settled in Mississippi.

Andrew Jackson argued that the solution to this problem was to move all these five tribes to Oklahoma. When Andrew Jackson gained power he encouraged Congress to pass the 1830 Indian Removal Act. He argued that the legislation would provide land for white invaders, improve security against foreign invaders and encourage the civilization of the Native Americans. In one speech he argued that the measure "will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the government and through the influences of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and christian community."

Jackson was re-elected with an overwhelming majority in 1832. He now pursued the policy of removing Native Americans from good farming land. He even refused to accept the decision of the Supreme Court to invalidate Georgia's plan to annex the territory of the Cherokee. This brought Jackson into conflict with Whig leaders such as Henry Clay and Daniel Webster.

The land given to the Native Americans in Oklahoma was known as the Indian Territory. The land was distributed in the following way: Choctaws (6,953,048 acres), Chickisaw (4,707,903 acres) and Cherokees (4,420,068). The tribes were also received money for their former lands: Cherokee ($2,716,979), Creek ($2,275,168), Seminole ($2,070,000), Chickisaw ($1,206,695) and Choctaw ($975,258). Some of these tribes used this money to buy land in Oklahoma and to support the building of schools.

In 1835 some leaders of the Cherokee tribe signed the Treaty of New Echota. This agreement ceded all rights to their traditional lands to the United States. In return the tribe was granted land in the Indian Territory. Although the majority of the Cherokees opposed this agreement they were forced to make the journey by General Winfield Scott and his soldiers. In October 1838 about 15,000 Cherokees began what was later to be known as the Trail of Tears. Most of the Cherokees travelled the 800 mile journey on foot. As a result of serious mistakes made by the Federal agents who guided them to their new land, they suffered from hunger and the cold weather and an estimated 4,000 people died on the journey.

Overall it is believed that about 70,000 Native Americans were forced to migrate from Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Virginia, Tennessee and Florida to Oklahoma. During the journey many died as a result of famine and disease.

The Federal government provided food and other supplies to the reservations and appointed an Indian Agent to live with the Native Americans. It was the job of the agent to teach them how to farm and to help protect them from unscrupulous traders.

On 27th January, 1861, Apaches stole cattle and kidnapped a boy from a Sonoita Valley ranch. Second Lieutenant George Bascom was sent out with 54 soldiers to recover the boy. Cochise met Bascom and told him that he would try to recover the boy. Bascom rejected the offer and instead tried to take Cochise hostage. When he tried to flee he was shot at by the soldiers. The wounded Cochise now gave orders for the execution of four white men being held in captivity. In retaliation six Apaches were hanged. Open warfare now broke out and during the next 60 days 150 white people were killed and five stage stations destroyed.

Mangas Coloradas and Cochise killed five people during an attack on a stage at Stein's Peak, New Mexico. In July, 1861 a war party murdered six white people travelling on a stage coach at Cooke's Canyon. The following year Cochise ambushed soldiers as they travelled through the Apache Pass. The Apaches also attacked stage coaches and in 1869 killed a Texas cowboy and stole 250 cattle. Cochise and his men were pursued but after a fight near Fort Bowie the soldiers were forced to retreat.

On 15th August, 1865, Kicking Bird signed a peace treaty with the American authorities at Wichita. He also took part in negotiations that resulted in the signing of the Medicine Lodge Treaty on 21st October, 1867. Under the terms of this treaty the Kiowa tribe moved to a reservation at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

Satanta negotiated several treaties with the American government including Little Arkansas (1865) and Medicine Lodge (1867). Satanta agreed that the Kiowas would live on a Indian Reservation. However, when they delayed their move Satanta was seized by General George A. Custer and held as a hostage until the migration took place.

In 1872 General Oliver Howard had a meeting with Cochise in the Dragoon Mountains and eventually it was agreed that a reservation would be established for the Chiricahuas in Arizona.

In December, 1875 the Commissioner of Indian Affairs directed all Sioux bands to enter reservations by the end of January 1876. Sitting Bull, now a medicine man and spiritual leader of his people, refused to leave his hunting grounds. Crazy Horse agreed and led his warriors north to join up with Sitting Bull.

In June 1876 Sitting Bull subjected himself to a sun dance. This ritual included fasting and self-torture. During the sun dance Sitting Bull saw a vision of a large number of white soldiers falling from the sky upside down. As a result of this vision he predicted that his people were about to enjoy a great victory.

On 17th June 1876, General George Crook and about 1,000 troops, supported by 300 Crow and Shoshone, fought against 1,500 members of the Sioux and Cheyenne tribes. The battle at Rosebud Creek lasted for over six hours. This was the first time that Native Americans had united together to fight in such large numbers.

General George A. Custer and 655 men were sent out to locate the villages of the Sioux and Cheyenne involved in the battle at Rosebud Creek. An encampment was discovered on the 25th June. It was estimated that it contained about 10,000 men, women and children. Custer assumed the numbers were much less than that and instead of waiting for the main army under General Alfred Terry to arrive, he decided to attack the encampment straight away.

Custer divided his men into three groups. Captain Frederick Benteen was ordered to explore a range of hills five miles from the village. Major Marcus Reno was to attack the encampment from the upper end whereas Custer decided to strike further downstream.

Reno soon discovered he was outnumbered and retreated to the river. He was later joined by Benteen and his men. Custer continued his attack but was easily defeated by about 4,000 warriors. At the battle of the Little Bighorn Custer and all his 264 men were killed. The soldiers under Reno and Benteen were also attacked and 47 of them were killed before they were rescued by the arrival of General Alfred Terry and his army.

The U.S. army now responded by increasing the number of the soldiers in the area. As a result Sitting Bull and his men fled to Canada, whereas Crazy Horse and his followers surrendered to General George Crook at the Red Cloud Agency in Nebraska. Crazy Horse was later killed while being held in custody at Fort Robinson.

In 1877 General Otis Howard instructed Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce tribe to move from their tribal lands in Oregon. Joseph eventually agreed to leave the Wallowa Valley and along with 350 followers settled in Whitebird Creek in Idaho. Around 190 young men rebelled against this decision and attacked white settlers in what became known as the Nez Perce War. Joseph's brother, Sousouquee, was killed during this fighting. Although he had no experience as a warrior, Joseph took part in the battles at White Bird Canyon (17th June), Clearwater (11th July) and at Bear Paw Mountain (30th September).

Chief Joseph and his men began a 1,300 mile march to Canada. However, on 5th October, 1877, the Nez Perce were surrounded by troops only 30 miles from the Canadian border. Joseph now agreed to take part in negotiations with General Nelson Miles. During the meeting Joseph was seized and beaten-up. Nez Perce warriors retaliated by capturing Lieutenant Lovell Jerome. A few weeks later Joseph was released in exchange for Lieutenant Jerome.

Chief Joseph continued to negotiate with General Miles. He also visited Washington where he met President William McKinley and President Theodore Roosevelt . Eventually some members of the Nez Perce tribe were allowed to return home but others were forced to live on the Colville Reservation. Joseph remained with them and did what he could to encourage his people to go to school and to discourage gambling and drunkenness.

The final resistance to white settlement in America was led by Geronimo, the leader of the Chiricahua Apaches in Arizona. In 1876 the American government ordered the Chiricahuas from their mountain homeland to the San Carlos Reservation. Geronimo refused to go and over the next few years he led a small band of warriors that raided settlements in Arizona. Geronimo also attacked American troops in the Whetstone Mountains, Arizona, on 9th January, 1877. This was followed by a rare defeat in the Leitendorf Mountains.

Geronimo was captured when entering the Ojo Caliente Reservation in New Mexico. Geronimo was eventually released and by April 1878 he was leading war parties in Mexico. The following year Geronimo surrendered and settled on the San Carlos Reservation.

In 1878 Nathan Meeker became the Indian agent of the White River Agency. He upset the Utes by trying to force them to become farmers. In September, 1879, Meeker called in the army to deal with the Utes. When he heard what was happening, Chief Douglas and a group of warriors killed Meeker and seven other members of the agency. This became known as the Meeker Massacre. The Utes also attacked Major Thomas Thornburgh and his troops heading for the White River Agency. In the fighting Thornburgh and nine of his men were killed. After the arrival of reinforcements the Utes were evicted from Colorado and placed on a reservation in Utah.

Primary Sources

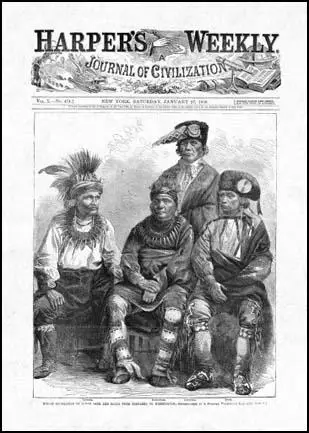

(1) Harper's Magazine (27th January, 1866)

We give on our first page portraits of four of the Indian delegates from Nebraska. The delegation, consisting altogether of eight Indians, arrived in Washington on the evening of January 2, in company with Major J. A. Burbank, United States Indian Commissioner for the Great Nebraska Agency. There were five Indians of the Iowa tribe and three of the Sac and Fox tribe. Three of our portraits are of Iowas, namely: Lag-er-lash, or British, Too-hi, or Brier Rose, and Tar-a-kee, or Deer-ham, the two first being half-civilized, while Deer-ham represents the wild portion of the tribe. Pe-ti-o-ki-ma, or Hard-fish, is a wild representative of the Sacs and Foxes.

Many of the delegation are dressed in wild aboriginal costume. Some years ago one of them, Moless, was sent to Kentucky, and received a very liberal English education, which, however, he failed to improve upon his return to his native wilds, and consequently he derived but little benefit from it. George Gomez, the interpreter of the Sacs and Foxes, is a fearfully ugly old fellow, who, report among his people says, has had seventy-five or eighty wives.

The tribes represented by this delegation occupy fifty sections of land, are surrounded by whites, and are quiet and peaceable. The Iowas are the most thrifty; cultivate their lands, and carry on extensive dealings in wood. One of the delegation, Mah-hoe, or The Knife, has an extensive wood yard on the Missouri River, and Major Burbank thinks that, next to the Cherokees, they are the most civilized of the Indian tribes. They are also truly loyal to the Government of the United States, and during the late war the Iowas sent over one-half of their braves into the Union army. They served principally in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Kansas regiments, but many were scattered among Missouri and other border regiments.

The main object of the present visit is to have a "talk" with regard to a treaty made in 1861, and to have it renewed. When they sold their lands to the Government, they understood the agreement to be that they were to receive the purchase-money in hand. The United States hold the principal, however, and the Indians are regularly paid the interest.

But of course the enjoyment is partly the object of their visit, for an Indian considers it one of the greatest events of his life to visit Washington and see his "Great Father," and nothing gives him more pleasure, or makes him think himself, or be esteemed by others of his tribe, a great man, than when he can rehearse to a listening audience what he has seen and heard on his travels. They will also carry back with them new silver peace medals, a number of which are now being struck at the Philadelphia Mint. The medals for President Johnson are of full size. On the face is an excellent cast of the President, with the words, "Andrew Johnson, President of the United States." On the reverse is a pedestal bearing in a wreath of laurel leaves the word "Peace." In front of the pedestal two figures - an Indian and America - are clasping hands. At the feet of the Indian lie the pipe of peace and the tomahawk, and in the back-ground are a herd of buffaloes. In the back-ground, near America, are represented a train of cars passing over a bridge, and a binnacle wheel and an anchor lie at her feet. The medals are beautifully designed, and are about two inches and a half in diameter.

(2) Chicago Tribune (7th July, 1876)

It is time to quit this Sunday-school policy, and let Sheridan recruit regiments of Western pioneer hunters and scouts, and exterminate every Indian who will not remain upon the reservations. The best use to make of an Indian who will not stay on a reservation is to kill him. It is time that the dawdling, maudlin peace-policy was abandoned. The Indian can never be subdued by Quakers, and it is certain that he will never by subdued by such madcap charges as that made by Custer.

(3) Reverend D. J. Burrell, sermon in Chicago on the battle of the Little Bighorn (August, 1876)

Who shall be held responsible for this event so dark and sorrowful? The history of our dealings with these Indian tribes from the very beginning is a record of fraud, and perjury, and uninterrupted injustice. We have made treaties, binding ourselves to the most solemn promises in the name of God, intending at that very time to hold these treaties light as air whenever our convenience should require them to be broken.... We have driven them each year further from their original homes and hunting-grounds.... We have treated them as having absolutely no rights at all.... We have made beggars of them

(4) General George Crook, Army and Navy Journal (29th June, 1878)

In regard to the Bannocks, I was up there last spring, and found them in a desperate condition. I telegraphed, and the agent telegraphed for supplies, but word came that no appropriation had been made. They have never been half supplied.

The agent has sent them off for half a year to enable them to pick up something to live on, but there is nothing for them in that country. The buffalo is all gone, and an Indian can't catch enough jack rabbits to subsist himself and his family, and then, there aren't enough jack rabbits to catch. What are they to do?

Starvation is staring them in the face, and if they wait much longer, they will not be able to fight. They understand the situation, and fully appreciate what is before them.

The encroachments upon the Camas prairies was the cause of the trouble. These prairies are their last source of subsistence. They are covered with water from April till June or July, and there is a sort of root which grows in them, under water, which is very much like a sweet potato. A squaw can gather several bushels a day of them. Then they dig a hole and build a fire in it. After it is thoroughly heated, the roots are put in and baked, and when they are taken out they are very sweet and nice.

This root is their main source of food supply. I do not wonder, and you will not either that when these Indians see their wives and children starving, and their last source of supplies cut off, they go to war. And then we are sent out to kill them. It is an outrage.

All the tribes tell the same story. They are surrounded on all sides, the game is destroyed or driven away; they are left to starve, and there remains but one thing for them to do - fight while they can. Some people think the Indians do not understand these things, but they do, and fully appreciate the circumstances in which they are placed.

(5) Mary Jemison, A Narrative of the Life of Mary Jemison (1824)

The use of ardent spirits amongst the Indians, and the attempts which have been made to civilize and christianize them by the white people, has constantly made them worse and worse; increased their vices, and robbed them of many of their virtues; and will ultimately produce their extermination. I have seen, in a number of instances, the effects of education upon some of our Indians, who were taken when young, from their families, and placed at school before they had had an opportunity to contract many Indian habits, and there kept till they arrived to manhood; but I have never seen one of those but what was an Indian in every respect after he returned. Indians must and will be Indians, in spite of all the means that can be used for their cultivation in the sciences and arts.

(6) Isabella Bird, A Lady's Life in the Rocky Mountains (1879)

The Americans will never solve the Indian problem till the Indian is extinct. They have treated them after a fashion which has intensified their treachery and "devilry" as enemies, and as friends reduces them to a degraded pauperism, devoid of the very first elements of civilisation. The only difference between the savage and the civilised Indian is that the latter carries firearms and gets drunk on whisky. The Indian Agency has been a sink of fraud and corruption; it is said that barely thirty per cent of the allowance ever reaches those for whom it is voted; and the complaints of shoddy blankets, damaged flour, and worthless firearms are universal. "To get rid of the Injuns" is the phrase used everywhere. Even their "reservations" do not escape seizure practically; for if gold " breaks out" on them they are " rushed," and their possessors are either compelled to accept land farther west or are shot off and driven off.

(7) Nelson Miles, letter to the Secretary of State for War (1890)

The causes that led to the serious disturbance of the peace in the northwest last autumn and winter were so remarkable that an explanation of them is necessary in order to comprehend the seriousness of the situation. The Indians assuming the most threatening attitude of hostility were the Cheyennes and Sioux. Their condition my be stated as follows: For several years following their subjugation in 1877, 1878, and 1879 the most dangerous element of the Cheyennes and the Sioux were under military control. Many of them were disarmed and dismounted; their war ponies were sold and the proceeds returned to them in domestic stock, farming utensils, wagons, etc. Many of the Cheyennes, under the charge of military officers, were located on land in accordance with the laws of Congress, but after they were turned over to civil agents and the vase herds of buffalo and large game had been destroyed their supplies were insufficient, and they were forced to kill cattle belonging to white people to sustain life.

The fact that they had not received sufficient food is admitted by the agents and the officers of the government who have had opportunities of knowing. The majority of the Sioux were under the charge of civil agents, frequently changed and often inexperienced. Many of the tribes became rearmed and remounted. They claimed that the government had not fulfilled its treaties and had failed to make large enough appropriations for their support; that they had suffered for want of food, and the evidence of this is beyond question and sufficient to satisfy any unprejudiced intelligent mind. The statements of officers, inspectors, both of the military and the Interior departments, of agents, of missionaries, ad civilians familiar with their condition, leave no room for reasonable doubt that this was one of the principal causes. While statements may be made as to the amount of money that has been expended by the government to feed the different tribes, the manner of distributing those appropriations will furnish one reason for the deficit.

The unfortunate failure of the crops in the plains country during the years of 1889 and 1890 added to the distress and suffering of the Indians, and it was possible for them to raise but very little from the ground for self-support; in fact, white settlers have been most unfortunate, and their losses have been serious and universal throughout a large section of that country. They have struggled on from year to year; occasionally they would raise good crops, which they were compelled to sell at low prices, while in the season of drought their labor was almost entirely lost. So serious have been their misfortunes that thousands have left that country within the last few years, passing over the mountains to the Pacific slope or returning to the east of the Missouri or the Mississippi.

The Indians, however, could not migrate from one part of the United States to another; neither could they obtain employment as readily as white people, either upon or beyond the Indian reservations. They must remain in comparative idleness and accept the results of the drought-an insufficient supply of food. This created a feeling of discontent even among the loyal and well disposed and added to the feeling of hostility of the element opposed to every process of civilization.

(8) General George Crook, speech (June, 1879)

The Indian is a child of ignorance, and not all innocence. It requires a certain kind of treatment to deal with and develop him. One requisite in those who would govern him rightly is absolute honesty - a strict keeping of faith toward him. The other requisite is authority to control him, and that the means to enforce that authority be vested in the same individual.

I have had twenty-six years' experience with the Indians, and I have been among tribes where I spoke their language. I have known the Indians intimately - known them in their private relations - I think I understand the Indian character pretty well. They talk about breaking up their tribal relations. The Interior Department have frequently issued letters, etc., looking to that. It might as well try to break up a band of sheep. Give these Indians little farms, survey them, let them put fences around them, let them have their own horses, cows, sheep, things that they can call their own, and it will do away with tribal Indians.

When once an Indian sees that his food is secure, he does not care what the chief or any one else says. The great mistake these people make is that they go to looking after the spiritual welfare of the Indians before securing their physical. Of course, that is a thing to come after awhile.

If you will investigate all the Indian troubles, you will find that there is something wrong of this nature at the bottom of all of them, something relating to the supplies, or else a tardy and broken faith on the part of the general government.

(9) President Chester Arthur, speech (6th December, 1881)

Prominent among the matters which challenge the attention of Congress at its present session is the management of our Indian affairs. While this question has been a cause of trouble and embarrassment from the infancy of the Government, it is but recently that any effort has been made for its solution at once serious, determined, consistent, and promising success.

It has been easier to resort to convenient makeshifts for tiding over temporary difficulties than to grapple with the great permanent problem, and accordingly the easier course has almost invariably been pursued.

It was natural, at a time when the national territory seemed almost illimitable and contained many millions of acres far outside the bounds of civilized settlements, that a policy should have been initiated which more than aught else has been the fruitful source of our Indian complications.

I refer, of course, to the policy of dealing with the various Indian tribes as separate nationalities, of relegating them by treaty stipulations to the occupancy of immense reservations in the West, and of encouraging them to live a savage life, undisturbed by any earnest and well-directed efforts to bring them under the influences of civilization.

The unsatisfactory results which have sprung from this policy are becoming apparent to all.

As the white settlements have crowded the borders of the reservations, the Indians, sometimes contentedly and sometimes against their will, have been transferred to other hunting grounds, from which they have again been dislodged whenever their new-found homes have been desired by the adventurous settlers.

These removals and the frontier collisions by which they have often been preceded have led to frequent and disastrous conflicts between the races.

It is profitless to discuss here which of them has been chiefly responsible for the disturbances whose recital occupies so large a space upon the pages of our history.

We have to deal with the appalling fact that though thousands of lives have been sacrificed and hundreds of millions of dollars expended in the attempt to solve the Indian problem, it has until within the past few years seemed scarcely nearer a solution than it was half a century ago. But the Government has of late been cautiously but steadily feeling its way to the adoption of a policy which has already produced gratifying results, and which, in my judgment, is likely, if Congress and the Executive accord in its support, to relieve us ere long from the difficulties which have hitherto beset us.

For the success of the efforts now making to introduce among the Indians the customs and pursuits of civilized life and gradually to absorb them into the mass of our citizens, sharing their rights and holden to their responsibilities, there is imperative need for legislative action.

My suggestions in that regard will be chiefly such as have been already called to the attention of Congress and have received to some extent its consideration.

First. I recommend the passage of an act making the laws of the various States and Territories applicable to the Indian reservations within their borders and extending the laws of the State of Arkansas to the portion of the Indian Territory not occupied by the Five Civilized Tribes.

The Indian should receive the protection of the law. He should be allowed to maintain in court his rights of person and property. He has repeatedly begged for this privilege. Its exercise would be very valuable to him in his progress toward civilization.

Second. Of even greater importance is a measure which has been frequently recommended by my predecessors in office, and in furtherance of which several bills have been from time to time introduced in both Houses of Congress. The enactment of a general law permitting the allotment in severalty, to such Indians, at least, as desire it, of a reasonable quantity of land secured to them by patent, and for their own protection made inalienable for twenty or twenty-five years, is demanded for their present welfare and their permanent advancement.

In return for such considerate action on the part of the Government, there is reason to believe that the Indians in large numbers would be persuaded to sever their tribal relations and to engage at once in agricultural pursuits. Many of them realize the fact that their hunting days are over and that it is now for their best interests to conform their manner of life to the new order of things. By no greater inducement than the assurance of permanent title to the soil can they be led to engage in the occupation of tilling it.

The well-attested reports of the their increasing interest in husbandry justify the hope and belief that the enactment of such a statute as I recommend would be at once attended with gratifying results. A resort to the allotment system would have a direct and powerful influence in dissolving the tribal bond, which is so prominent a feature of savage life, and which tends so strongly to perpetuate it.

Third. I advise a liberal appropriation for the support of Indian schools, because of my confident belief that such a course is consistent with the wisest economy.