Scalping

The removal of the skin covering the top of a person head during or after a battle dates back to the Scythians (c. 400 BC). The Visigoths also took scalps during the wars with the Anglo-Saxons in the 9th century. When the Europeans first visited America they observed that the Huron, Chichimec, Iroquoi and Muskhogean tribes scalped enemy warriors. The Spanish administrator of Mexico, Francisco de Garay, reported in 1520 of seeing the "cutting of the skin off the entire head and face, with hair and beard". However, there is no evidence that the majority of Native American tribes at this time were involved in scalping.

In 1688, the French-Canadians began paying for every enemy scalp. This encouraged the emergence of groups trying to make a business out of scalping settlers. The British responded in 1693 by announcing that they would pay money for the scalps of Frenchmen and their Indian allies. As much as £100 was obtained for an important scalp.

In 1777, Jane McCrea, the fiancée of a soldier serving with General Burgoyne's army, was captured by Indians allied to the British. Then during a dispute between two warriors, Jane was scalped. General Burgoyne did not punish the guilty men for fear of breaking the alliance with that tribe. This decision enraged local Americans and many men now joined in the struggle against the British. It was later claimed that the death of Jane McCrea greatly aided the rebel cause and contributed to the defeat of Burgoyne's army at Saratoga. The incident continued to be used as propaganda against the English and the story was immortalized by John Vanderlyn's painting, The Death of Jane McCrea, in 1804.

This policy of scalping spread to the Americans during the 19th century and they paid bounties for the scalps of troublesome tribes such as the Apache. The idea of scalping as an act of revenge was adopted by the Plains tribes during the Indian Wars.

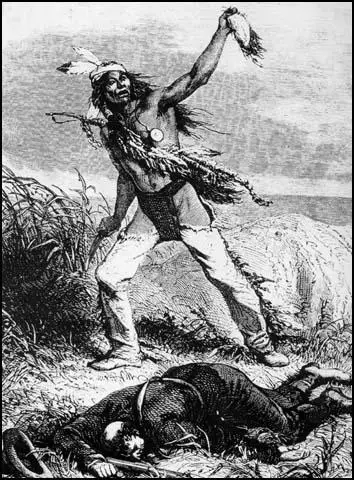

The scalp was usually taken from a dead enemy. Pierre Pouchot saw soldiers being scalped in about 1760: "As soon as the man is felled, they run up to him, thrust their knee in between his shoulder blades, seize a tuft of hair in one hand and, with their knife in the other, cut around the skin of the head and pull the whole piece away." Some warriors gained status by scalping a man during combat. This involved making a knife incision around the scalp lock and pulling the hair back very quickly. Although extremely painful, being scalped alive was not always fatal.

A full-scalping would often lead to serious medical complications. This included profuse bleeding, infection, and eventual death if the bone of the skull was left exposed. Death could also occur from septicemia, meningitis or necrosis of the skull.

The fashion of head shaving, except for a small lock of hair, on the crown of the head, developed amongst the Plains Indians. This hair covered about two inches in diameter and therefore only a minor wound would result from being scalped. However, it was a great insult for a Native American to be scalped while still alive. For example, the Arikara tribe would treat a scalped warrior as an outcast.

Native American tribes used scalping to persuade Americans from abandoning the idea of taking their land. Nelson Lee was unlucky enough to captured by the Comanche tribe. "During all the time they were thus exhibiting the result of their savage work, they resorted to every hideous device to inspire us with terror. They would rush toward us with uplifted tomahawks, stained with blood, as if determined to strike, or grasp us by the hair, flourishing their knives around our heads as though intending to take our scalps. So far as I could understand their infernal shouts and pantomime, they sought to tell us that the fate which had overtaken our unfortunate companions not only awaited us, but likewise the whole race of the hated white man. All the dead, without exception, were scalped and the scalps, still fresh, were dangling from their belts.

After the battle had finished the warrior would clean and dry the scalp. Thomas Gist witnessed this while he was being held prisoner. "The men began to scrape the flesh and blood from the scalps, and dry them by the fire, after which they dressed them with feathers and painted them, then tied them on white, red, and black poles".

Primary Sources

(1) Travels in New France by J. C. B (1760)

When a war party has captured one or more prisoners that cannot be taken away, it is the usual custom to kill them by breaking their heads with the blows of a tomahawk. When he has struck two or three blows, the savage quickly seizes his knife, and makes an incision around the hair from the upper part of the forehead to the back of the neck. Then he puts his foot on the shoulder of the victim, whom he has turned over face down, and pulls the hair off with both hands, from back to front . . . This hasty operation is no sooner finished than the savage fastens the scalp to his belt and goes on his way. This method is only used when the prisoner cannot follow his captor; or when the Indian is pursued . . . He quickly takes the scalp, gives the death cry, and flees at top speed. Savages always announce their valor by a death cry, when they have taken a scalp . . . When a savage has taken a scalp, and is not afraid he is being pursued, he stops and scrapes the skin to remove the blood and fibres on it. He makes a hoop of green wood, stretches the skin over it like a tambourine, and puts it in the sun to dry a little. The skin is painted red, and the hair on the outside combed. When prepared, the scalp is fastened to the end of a long stick, and carried on his shoulder in triumph to the village or place where he wants to put it. But as he nears each place on his way, he gives as many cries as he has scalps to announce his arrival and show his bravery. Sometimes as many as 15 scalps are fastened on the same stick. When there are too many for one stick, they decorate several sticks with the scalps.

(2) Thomas Gist, journal entry (14th September 14, 1758)

The men began to scrape the flesh and blood from the scalps, and dry them by the fire, after which they dressed them with feathers and painted them, then tied them on white, red, and black poles, which they made so by pealing the bark and then painting them as it suited them.

(3) Pierre Pouchot, Memoirs on the Late War in North America Between France and England (1765)

As soon as the man is felled, they run up to him, thrust their knee in between his shoulder blades, seize a tuft of hair in one hand and, with their knife in the other, cut around the skin of the head and pull the whole piece away. The whole thing is done very expeditiously. Then, brandishing the scalp, they utter a whoop which they call the 'death whoop'. . . If they are not under pressure and the victory has cost them lives, they behave in an extremely cruel manner towards those they kill or the dead bodies. They disembowel them and smear their blood all over themselves.

(4) Mary Jemison, A Narrative of the Life of Mary Jemison (1824)

It is a custom of the Indians, when one of their number is slain or taken prisoner in battle, to give to the nearest relative to the dead or absent, a prisoner, if they have chanced to take one, and if not, to give him the scalp of an enemy. On the return of the Indians from conquest, which is always announced by peculiar shoutings, demonstrations of joy, and the exhibition of some trophy of victory, the mourners come forward and make their claims. If they receive a prisoner, it is at their option either to satiate their vengeance, by taking his life in the most cruel manner they can conceive of; or, to receive and adopt him into the family, in the place of him whom they have lost. All the prisoners that are taken in battle and carried to the encampment or town by the Indians, are given to the bereaved families, till their number is made good. And unless the mourners have but just received the news of their bereavement, and are under the operation of a paroxysm of grief, anger and revenge; or, unless the prisoner is very old, sickly, or homely, they generally save him, and treat him kindly. But if their mental wound is fresh, their loss so great that they deem it irreparable, or if their prisoner or prisoners do not meet their approbation, no torture, let it be ever so cruel, seems sufficient to make them satisfaction. It is family, and not national, sacrifices amongst the Indians, that has given them an indelible stamp as barbarians, and identified their character with the idea which is generally formed of unfeeling ferocity, and the most abandoned cruelty.

(5) George Ruxton, Adventures in Mexico and the Rocky Mountains (1847)

Seizing with his left hand the long and braided lock on the centre of the Indian's head, he passed the point edge of his keen butcher-knife round the parting, turning it at the same time under the skin to separate the scalp from the skull; then, with a quick and sudden jerk of his hand, he removed it entirely from the head, and giving the reeking trophy a wring upon the grass to free it from the blood, he coolly hitched it under his belt, and proceeded to the next; but seeing La Bonte operating upon this, he sought the third, who lay some little distance from the others. This one was still alive, a pistol-ball having passed through his body, without touching a vital spot. Thrusting his knife, for mercy's sake, into the bosom of the Indian, he likewise tore the scalp-lock from his head, and placed it with the other.

(6) Anna Jameson, Winter Studies and Summer Rambles (1838)

Apropos to scalps, I have seen many of the warriors here, who had one or more of these suspended as decorations to their dress; and they seemed to me so much a part and parcel of the sauvagerie around me, that I looked on them generally without emotion or pain. But there was one thing I never could see without a start, and a thrill of horror - the scalp of long fair hair.

(7) Lewis Morgan, Kansas and Nebraska Journal (June, 1859)

The Minnetaree village is a large village of dirt houses. Soon after we arrived the people who crowded the bank commenced a scalp dance on the top of the bluff in front of the pickets. They used two drums, like tambourines, which were beat by the dancers themselves, and they danced in a ring from right to left about 30 in all, one-third of them women. They all danced. The women sang in a sort of chorus, with their voices an octave above those of the men. The step was the up and down on the heel step. They were celebrating the taking of the Sioux scalp we heard complained of at Fort Pierre. This morning I met the 3 who took the scalp, painted and dressed, coming through the village towards the boat, and walking side and slide, singing their exploit. The dance, the song, the music, and the step among all our Indians came out of one brain.

(8) Nelson Lee, Three Years Among the Comanches (1859)

I soon became aware that the only members of the party who escaped the massacre, which proved to have been bloody as it was sudden, were Thomas Martin, John Stewart, Atkins, and myself.

Their next step was to collect the plunder. In this, they were, indeed, thorough. Not only did they gather up all our buffalo skins, Mexican blankets, rifles and revolvers, culinary utensils, and the like, but the dead bodies were stripped to the last shred, and tied on the backs of their mules. Nothing was left behind. By this time the morning light began to break on the eastern mountains, and preparations were made to depart. Before starting, however, they unbound our feet, conducted us through the camp, pointing out the stark corpses of our butchered comrades, who had lain down to sleep with such light and happy hearts the night before. The scene was awful and heart-rending beyond the imagination of man to conceive. Not satisfied with merely putting them to death, they had cut and hacked the poor, cold bodies in the most brutal and wanton manner; some having their arms and hands chopped off, others emboweled, and still others with their tongues drawn out and sharp sticks thrust through them. They then led us out some three or four hundred yards from the camp and pointed out the dead bodies of the sentinels, thus assuring us that not one of the entire party had escaped.

During all the time they were thus exhibiting the result of their savage work, they resorted to every hideous device to inspire us with terror. They would rush toward us with uplifted tomahawks, stained with blood, as if determined to strike, or grasp us by the hair, flourishing their knives around our heads as though intending to take our scalps. So far as I could understand their infernal shouts and pantomime, they sought to tell us that the fate which had overtaken our unfortunate companions not only awaited us, but likewise the whole race of the hated white man. All the dead, without exception, were scalped and the scalps, still fresh, were dangling from their belts.

(9) Mary Smith, included in the History of La Salle County (1877)

The report of the unfortunate young women (Frances and Almira Hall) communicated to their friends and relatives, on their return from captivity, although treated with less severity, cannot fail to be read with much interest - they state, that after being compelled to witness not only the savage butchery of their beloved parents, but to hear the heart-piercing screeches and dying groans of their expiring friends and neighbors, and the hideous yells of the furious assaulting savages, they were seized and mounted upon horses, to which they were secured by ropes, when the savages with an exulting shout, took up their line of march in Indian file, bending their course west; the horses on which the females were mounted, being each led by one of their number, while two more walked on each side with their bloodstained scalping knives and tomahawks, to support and to guard them - they thus travelled for many hours, with as much speed as possible through a dark and almost impenetrable wood; when reaching a still more dark and gloomy swamp, they came to a halt. A division of the plunder which they had brought from the ill-fated settlement, and with which their stolen horses (nine in number) were loaded, here took place, each savage stowing away in his pack his proportional share as he received it; but on nothing did they seem to set so great a value, or view with so much satisfaction, as the bleeding scalps which they had, ere life had become extinct torn from the mangled heads of the expiring victims! the feelings of the unhappy prisoners at this moment, can be better judged than described when they could not be insensible that among these scalps, these shocking proofs of savage Cannibalism, were those of their beloved parents! but their moans and bitter lamentations had no effect in moving or diverting for a moment the savages from the business in which they had engaged, until it was competed; when, with as little delay as possible, and without giving themselves time to partake of any refreshment, (as the prisoners could perceive) they again set forward, and travelled with precipitancy until sunset when they again halted, and prepared a temporary lodging for the night-the poor unfortunate females, whose feelings as may be supposed, could be no other than such as bordered on distraction, and who had not ceased for a moment to weep most bitterly during the whole day, could not but believe that they were here destined to become the victims of savage outrage and abuse; and that their sufferings would soon terminate, as they would not (as they imagined) be permitted to live to see the light of another day!

(10) Herman Lehmann, Indianology (1899)

That night we came in contact with a company of men and had a little fight. We killed one white man and captured fifteen horses. I think this must have been near Ballinger. We came down to Pack Saddle in Llano County and there had a terrible fight with four white men. We were in the roughs and so were the whites, so neither had the advantage, but we routed them in about a half hour. I think I wounded one of the white men severely. I had a good shot at him, but they all got away.

We wended our way from there to House mountains, and there we captured a nice herd of horses, and this increased our drove to fifty. We went our same old route up the Llano river, but the rangers got on our trail and followed us up through Mason county, but we made for Kickapoo Springs, but the rangers had changed horses and were giving us close chase. We changed horses often and rode cautiously and made our escape, but we were followed to the edge of the plains. We reached home safely and with all our horses, but the Mexicans had again joined our squaws, and this time they had plenty of mescal and corn whiskey, and tobacco in abundance. We all got drunk and one hundred and forty Indian warriors and sixty Mexicans went on a cattle raid. West of Fort Griffin, on the old trail, we ran into a big herd being driven to Kansas. There were about twenty hands with the cattle. We rushed up and opened fire. The cattle stampeded and the cowboys rode in an opposite direction. There were enough of us to surround the cattle and chase the boys. We soon gave the boys up and started for Mexico with the herd, but the second day we were overtaken by about forty white men, who tried to retake the cattle, and in the attempt two Mexicans and one Indian were killed - the Indian was shot through the neck - and we had four horses killed. We repulsed them and got possession of two of their dead, who were promptly scalped. We put the scalps of those boys on high poles and had a big feast and war dance. We slew forty beeves and roasted them all at once. We kept up a chant and dance around those scalps day and night.

(11) John F. Finerty, Warpath and Bivouac (1890)

The skull of one poor squaw was blown, literally, to atoms, revealing the ridge of the palate and presenting a most ghastly and revolting spectacle. Another of the dead females, a middle-aged woman, was so riddled by bullets that there appeared to be no unwounded part of her person left. The third victim was young, plump, and, comparatively speaking, light of color. She had a magnificent physique, and, for an Indian, a most attractive set of features. She had been shot through the left breast just over the heart and was not in the least disfigured.

Ute John, the solitary friendly Indian who did not desert the column, scalped all the dead, unknown to the General or any of the officers, and I regret to be compelled to state a few - a very few - brutalized soldiers followed his savage example. Each took only a portion of the scalp, but the exhibition of human depravity was nauseating. The unfortunates should have been respected, even in the coldness and nothingness of death. In that affair, surely, the army were the assailants and the savages acted purely in self defense. I must add in justice to all concerned that neither General Crook nor any of his officers or men suspected that any women or children were in the gully until their cries were heard above the volume of fire poured upon the fatal spot.