On this day on 23rd February

On this day in 1643 Henrietta Maria writes a letter to her husband King Charles I. on the English Civil War. Henrietta Maria had gone to Holland to raise funds for the royalist army. On her journey back her ship was chased by four Parliamentary ships. "All day we unloaded our ammunition... The cannon balls whistled over me; and as you can imagine I did not like the music... I went on foot some distance from the village, and got shelter in a ditch. But before I could reach it the balls sang merrily over our heads and a sergeant was killed twenty paces from me. Under this shelter we remained two hours, the bullets flying over us, and sometimes covering us with earth... by land and sea I have been in some danger, but God has preserved me."

On this day in 1633 Samuel Pepys is born. Pepys, the son of a tailor, John Pepys, was born in London in 1633. After being educated at St. Paul's School and Magdalene College, Cambridge, he found work as secretary to Sir Edward Montagu.

On the Restoration Montagu was given command of the royal fleet. With the help of Montagu, Pepys was appointed Clerk of the King's Ships. This was followed by Pepys becoming Survey-General of the Victualling Service (1665) and Secretary of the Admiralty (1672).

In 1678 Titus Oates announced that he had discovered a Catholic plot to kill Charles II. Oates claimed that Charles was to be replaced by his Roman Catholic brother, James. He went on to argue that after James came to the throne Protestants would be massacred in their thousands. The government believed the story and eighty people were arrested and accused of taking part in the plot. This included Pepys who was imprisoned in the Tower of London. Several people were executed, including Oliver Plunkett, the Archbishop of Armagh, before it was revealed that Titus Oates had been lying.

Pepys was released and in 1683 and the following year was reinstated as Secretary to the Admiralty. However, he was forced to resign after James II was ousted from power and replaced by the joint monarchs, William III and Mary II. Pepys was imprisoned by the new government and was not released until 1700. Samuel Pepys died in 1703.

Samuel Pepys, like his friend, John Evelyn, kept a diary and on his death was left to the library at Magdalene College. The diary was in code and was not deciphered and published until 1825. The diaries cover the period from January 1660 to May 1669.

On this day in 1792 Joshua Reynolds died of liver disease at his home at 47 Leicester Square, London. Reynolds, the seventh of ten children of Samuel Reynolds (1681–1745), schoolmaster, and his wife, Theophila Potter (1688–1756), was born at Plympton, Devon on 16th July, 1723. His his great-grandfather was the eminent mathematician, Thomas Baker.

Reynolds was educated by his father. According to his biographer, Martin Postle: "Classes were small and the curriculum, in line with more advanced Lockean precepts, would have extended beyond the parameters of classical scholarship, to include geography, arithmetic, and drawing. In addition to his teaching Reynolds's father maintained regular correspondence with friends on topics ranging from medicine to metaphysics. He observed the stars through his telescope, cast horoscopes, and wrote treatises on subjects as diverse as theology and gout."

Reynolds took a keen interest in painting. His first recorded portrait, made at the age of twelve, dates from 1735. The subject was a local clergyman named Thomas Smart. In 1740 he was apprenticed to the artist, Thomas Hudson, whose studio was at Lincoln's Inn Fields in London. His work for Hudson involved running errands, preparing canvases and painting accessories in portraits. He later complained that he regretted that he had not received a proper academic training, lacking "the facility of drawing the naked figure, which an artist ought to have".

By 1743 Reynolds had established himself as a portrait artist. The author of Joshua Reynolds: The Creation of Celebrity (2005) has argued: "The few surviving portraits of this period, notably those of the Kendall family, indicate that Reynolds was then working very much in the manner of Hudson, turning out competent, if unexceptional, works. Reynolds's burgeoning talent emerges more clearly in the portraits of his immediate family, painted about 1745–6, notably those of his sister Frances (known as Fanny) Reynolds, his father, and his own self-portrait. The principal pictorial influence on all three portraits is Rembrandt, the artist who was to influence Reynolds more profoundly than any other, especially in his earlier career. During this period Reynolds also painted a number of self-portraits in the manner of Rembrandt, of which the most celebrated shows him peering out towards the viewer, shading his eyes with his hand."

Reynolds took a house in Devonport with his two unmarried sisters, Fanny and Jane. Most of his clients lived in London and in 1747 he established a studio in St Martin's Lane. During this period he became friendly with John Wilkes. In November 1748 The Universal Magazine named Reynolds as one of the nation's most important artists.

In 1749 Reynolds travelled to the Mediterranean. This included visits to Lisbon, Cadiz, Morocco, and Minorca. In March 1750 he arrived in Rome. Over the next few months he made copies of old-master paintings. Reynolds later recalled: "I found myself in the midst of works executed upon principles with which I was unacquainted: I felt my ignorance and stood abashed. Notwithstanding my disappointment, I proceeded to copy some of those excellent works. I viewed them again and again; I even affected to admire them, more than I really did."

In May 1752, Reynolds arrived in Florence. After two months copying paintings he moved to Venice where he spent time with the Italian painter Francesco Zuccarelli. That summer he also visited Padua, Milan, Turin and Paris and arrived back in London on 16th October, 1752.

Reynolds resumed his portrait practice at 104 St Martin's Lane. It has been claimed that William Dobson, William Hogarth and Allan Ramsay had the most influence of his style. Reynolds produced over 100 portraits a year. The author of Joshua Reynolds: The Creation of Celebrity (2005) has pointed out: "And as he became more successful so his prices rose accordingly. In 1753 he charged 48 guineas for a full-length portrait; by 1759 the price had risen to 100 guineas, and by 1764 to 150 guineas".

Those painted by Reynolds included Josiah Wedgwood, Francis Barber, Lord Palmerston, Warren Hastings, Samuel Johnson, James Boswell, Henry Thrale, Laurence Sterne, Joseph Banks, Edmund Burke, Oliver Goldsmith and David Garrick. According to one sitter "Reynolds would... walk away several feet, then take a long look at me and the picture as we stood side by side, then rush up to the portrait and dash at it in a kind of fury. I sometimes thought he would make a mistake and paint on me instead of the picture".

When the Royal Academy was established in 1768, Reynolds was elected its first president. The following year George III knighted Reynolds at St James's Palace. His biographer has argued: "Reynolds's greatest critic within the Royal Academy was James Barry, who in 1782 was elected as its professor of painting. Barry's differences with Reynolds were primarily ideological. Even so, he used his position and his annual academy lectures to mount increasingly personal attacks on Reynolds."

According to Martin Postle: "Reynolds was about 5 feet 6 inches tall, with ruddy, rounded facial features. He was partially deaf, which caused him in later life to affect a large silver ear-trumpet. He blamed the affliction upon a chill caught in the Sistine Chapel, although it was probably hereditary, as was his slight harelip.... Among friends, of whom he had many of both sexes, Reynolds was admired for his generosity, even temper, and capacity for listening. His dinner parties were notorious for their air of anarchic bonhomie, Reynolds invariably inviting far more guests than could be accommodated at his table."

Following the death of Allan Ramsay in 1784 Reynolds was appointed as painter to George III. However, five years later his sight began to deteriorate and he was forced to give up painting. The Morning Herald reported: "Sir Joshua feels his sight so infirm as to allow of his painting about thirty or forty minutes at a time only and he means in a certain degree to retire."

In 1788, Reynolds told James Boswell he had never married, because "every woman whom he had liked had grown indifferent to him". Fanny Burney was a regular visitor. He told her in January 1793: "I am very glad to see you again, and I wish I could see you better! but I have but one eye now, and scarcely that."

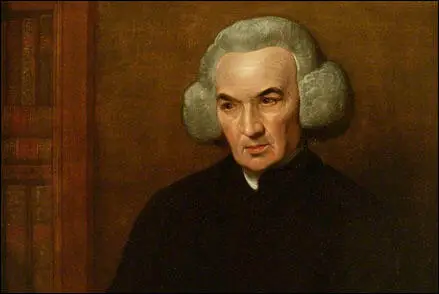

On this day in 1723 philosopher Richard Price is born. Price, the son of Rice Price, a Congregational minister, was born in Tynton, Glamorgan in 1723. From an early age he appears to have rejected his father's religious opinions and instead was attracted to the views of more liberal theologians.

Price attended a Dissenting Academy in London and afterwards became a chaplain in Stoke Newington. In 1756 he married Sarah Blundell and two years later moved to Newington Green, a small village near Hackney.

In 1758 Price wrote the very influential Review of the Principal Questions of Morals. In the book Price argued that individual conscience and reason should be used when making moral choices. Price also rejected the traditional Christian ideas of original sin and eternal punishment. Price and his friend, Joseph Priestley, became leaders of a group of men called Rational Dissenters.

Richard Price was also friendly with the mathematician Thomas Bayes. After Bayes's death in 1761, his relatives asked Price to examine his unpublished papers. Price realized their importance and submitted, An Essay Towards Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances to the Royal Society. In this work, Price, using the information provided by Bayes, introduced the idea of estimating the probability of an event from the frequency of its previous occurrences.

In 1765 Price was admitted to the Royal Society for his work on probability. He also began collecting information on life expectation and in May 1770 he wrote to the Royal Society about the proper method of calculating the values of contingent reversions. It is believed that this information drew attention to the inadequate calculations on which many insurance and benefit societies had recently been formed.

Other books by Price include Observations on Reversionary Payments (1771), An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the National Debt (1772) and Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty, the Principles of Government, and the Justice and Policy of War with America (1776).

In 1784 Richard Price met Mary Wollstonecraft who had opened a school in Newington Green. Although Mary was brought up as an Anglican, she soon began attending Richard Price's chapel. Others who visited Price in Newington Green included John Howard, John Quincy Adams, Adam Smith and Benjamin Franklin. Price was a true libertarian and laboured throughout his life to increase intellectual, political and spiritual freedom for all people.

In November, 1789, Richard Price preached a sermon praising the French Revolution. Price argued that British people, like the French, had the right to remove a bad king from the throne. He told his congregation that he could "depart in peace, for mine eyes have seen Thy salvation."

Edmund Burke, was appalled by this sermon and wrote a reply called Reflections on the Revolution in France, where he argued in favour of the inherited rights of the monarchy. Mary Wollstonecraft was upset by Burke's attack on her friend and she decided to defend him by writing a pamphlet A Vindication of the Rights of Man. In her pamphlet Wollstonecraft not only supported Price but also pointed out what she thought was wrong with society.

Price was attracted to the ideas of Jeremy Bentham. Price accepted many aspects of Bentham's unitarianism, especially his views on political libertarianism and his opposition to Christian orthodoxy. However, unlike other unitarians, Price was unwilling to question the divinity of Christ. In 1791 he became one of the original members of the Unitarian Society.

Richard Price died on 19th April, 1791. His funeral was conducted at Bunhill Fields and his funeral sermon was preached by Joseph Priestley.

On this day in 1820 George Edwards, a gpolice spy, informed John Stafford, who worked at the Home Office, about the Cato Street Conspiracy.

In 1793 Thomas Spence started a periodical, Pigs' Meat. He said in the first edition: "Awake! Arise! Arm yourselves with truth, justice, reason. Lay siege to corruption. Claim as your inalienable right, universal suffrage and annual parliaments. And whenever you have the gratification to choose a representative, let him be from among the lower orders of men, and he will know how to sympathize with you."

By the early 1800s Spence had established himself as the unofficial leader of those Radicals who advocated revolution. James Watson, was one of the men who worked very closely with Spence during this period. Spence did not believe in a centralized radical body and instead encouraged the formation of small groups that could meet in local public houses. At the night the men walked the streets and chalked on the walls slogans such as "Spence's Plan and Full Bellies" and "The Land is the People's Farm". In 1800 and 1801 the authorities believed that Spence and his followers were responsible for bread riots in London. However, they did not have enough evidence to arrest them.

Thomas Spence died in September 1814. He was buried by "forty disciples" who pledged that they would keep his ideas alive. They did this by forming the Society of Spencean Philanthropists. The men met in small groups all over London. These meetings mainly took place in public houses and they discussed the best way of achieving an equal society. Places used included the Mulberry Tree in Moorfields, the Carlisle in Shoreditch, the Cock in Soho, the Pineapple in Lambeth, the White Lion in Camden, the Horse and Groom in Marylebone and the Nag's Head in Carnaby Market. The government became very concerned about this group that they employed a spy, John Castle, to join the Spenceans and report on their activities.

The government remained concerned about the Spenceans and John Stafford, who worked at the Home Office, recruited George Edwards, George Ruthven, John Williamson, John Shegoe, James Hanley and Thomas Dwyer to spy on this group. The Peterloo Massacre in Manchester increased the amount of anger the Spenceans felt towards the government. At one meeting a spy reported that Arthur Thistlewood said: "High Treason was committed against the people at Manchester. I resolved that the lives of the instigators of massacre should atone for the souls of murdered innocents."

On 22nd February 1820, George Edwards pointed out to Arthur Thistlewood an item in a newspaper that said several members of the British government were going to have dinner at Lord Harrowby's house at 39 Grosvenor Square the following night. Thistlewood argued that this was the opportunity they had been waiting for. It was decided that a group of Spenceans would gain entry to the house and kill all the government ministers. According to the reports of spies the heads of Lord Castlereagh and Lord Sidmouth would be placed on poles and taken around the slums of London. Thistlewood was convinced that this would incite an armed uprising that would overthrow the government. This would be followed by the creation of a new government committed to creating a society based on the ideas of Thomas Spence.

Over the next few hours Thistlewood attempted to recruit as many people as possible to take part in the plot. Many people refused and according to the police spy, George Edwards, only twenty-seven people agreed to participate. This included William Davidson, James Ings, Richard Tidd, John Brunt, John Harrison, James Wilson, Richard Bradburn, John Strange, Charles Copper, Robert Adams and John Monument.

William Davidson had worked for Lord Harrowby in the past and knew some of the staff at Grosvenor Square. He was instructed to find out more details about the cabinet meeting. However, when he spoke to one of the servants he was told that the Earl of Harrowby was not in London. When Davidson reported this news back to Arthur Thistlewood, he insisted that the servant was lying and that the assassinations should proceed as planned.

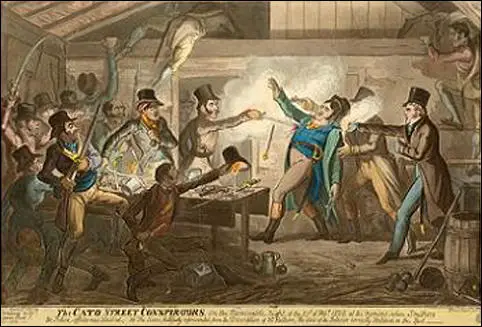

One member of the gang, John Harrison, knew of a small, two-story building in Cato Street that was available for rent. The ground-floor was a stable and above that was a hayloft. As it was only a short distance from Grosvenor Square, it was decided to rent the building as a base for the operation. Edwards told Stafford of the plan and Richard Birnie, a magistrate at Bow Street, was put in charge of the operation. Lord Sidmouth instructed Birnie to use men from the Second Battalion Coldstream Guards as well as police officers from Bow Street to arrest the Cato Street Conspirators.

Birnie decided to send George Ruthven, a police officer and former spy who knew most of the Spenceans, to the Horse and Groom, a public house that overlooked the stable in Cato Street. On 23rd February, Ruthven took up his position at two o'clock in the afternoon. Soon afterwards Thistlewood's gang began arriving at the stable. By seven thirty Richard Birnie and twelve police officers joined Ruthven at Cato Street.

The Coldstream Guards had not arrived and Birnie decided he had enough men to capture the Cato Street Gang. Birnie gave orders for Ruthven to carry out the task while he waited outside. Inside the stable the police found James Ings on guard. He was quickly overcome and George Ruthven led his men up the ladder into the hayloft where the gang were having their meeting. As he entered the loft Ruthven shouted, "We are peace officers. Lay down your arms." Arthur Thistlewood and William Davidson raised their swords while some of the other men attempted to load their pistols. One of the police officers, Richard Smithers, moved forward to make the arrests but Thistlewood stabbed him with his sword. Smithers gasped, "Oh God, I am..." and lost consciousness. Smithers died soon afterwards. (8)

Some of the gang surrendered but others like William Davidson were only taken after a struggle. Four of the conspirators, Thistlewood, John Brunt, Robert Adams and John Harrison escaped out of a back window. However, George Edwards had given the police a detailed list of all those involved and the men were soon arrested.

Eleven men were eventually charged with being involved in the Cato Street Conspiracy. After the experience of the previous trial of the Spenceans, Lord Sidmouth was unwilling to use the evidence of his spies in court. George Edwards, the person with a great deal of information about the conspiracy, was never called. Instead the police offered to drop charges against certain members of the gang if they were willing to give evidence against the rest of the conspirators. Two of these men, Robert Adams and John Monument, agreed and they provided the evidence needed to convict the rest of the gang.

James Ings claimed that George Edwards had worked as an agent provocateur: "The Attorney-General knows Edwards. He knew all the plans for two months before I was acquainted with it. When I was before Lord Sidmouth, a gentleman said Lord Sidmouth knew all about this for two months. I consider myself murdered if Edwards is not brought forward. I am willing to die on the scaffold with him. I conspired to put Lord Castlereagh and Lord Sidmouth out of this world, but I did not intend to commit High Treason. I did not expect to save my own life, but I was determined to die a martyr in my country's cause."

William Davidson said in court: "It is an ancient custom to resist tyranny... And our history goes on further to say, that when another of their Majesties the Kings of England tried to infringe upon those rights, the people armed, and told him that if he did not give them the privileges of Englishmen, they would compel him by the point of the sword... Would you not rather govern a country of spirited men, than cowards? I can die but once in this world, and the only regret left is, that I have a large family of small children, and when I think of that, it unmans me."

On 28th April 1820, Arthur Thistlewood, William Davidson, James Ings, Richard Tidd, and John Brunt were found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death. John Harrison, James Wilson, Richard Bradburn, John Strange and Charles Copper were also found guilty but their original sentence of execution was subsequently commuted to transportation for life.

Arthur Thistlewood, William Davidson, James Ings, Richard Tidd, and John Brunt were taken to Newgate Prison on 1st May, 1820. John Hobhouse attended the execution: "The men died like heroes. Ings, perhaps, was too obstreperous in singing Death or Liberty" and records Thistlewood as saying, "Be quiet, Ings; we can die without all this noise."

According to the author of An Authentic History of the Cato Street Conspiracy (1820). "Thistlewood struggled slightly for a few minutes, but each effort was more faint than that which preceded; and the body soon turned round slowly, as if upon the motion of the hand of death. Tidd, whose size gave cause to suppose that he would 'pass' with little comparative pain, scarcely moved after the fall. The struggles of Ings were great. The assistants of the executioner pulled his legs with all their might; and even then the reluctance of the soul to part from its native seat was to be observed in the vehement efforts of every part of the body. Davidson, after three or four heaves, became motionless; but Brunt suffered extremely, and considerable exertions were made by the executioners and others to shorten his agonies."

Richard Carlile told the wife of William Davidson. "Be assured that the heroic manner in which your husband and his companions met their fate, will in a few years, perhaps in a few months, stamp their names as patriots, and men who had nothing but their country's weal at heart. I flatter myself as your children grow up, they will find that the fate of their father will rather procure them respect and admiration than its reverse."

On this day in 1865 George Odger, Benjamin Lucraft, George Howell, William Allan, Johann Eccarius, William Cremer and several other members of the International Workingmen's Association established the Reform League, an organisation to campaign for one man, one vote. Karl Marx told Friedrich Engels "The International Association has managed so to constitute the majority on the committee to set up the new Reform League that the whole leadership is in our hands".

The Reform League received financial and political support from middle-class radicals such as Peter Alfred Taylor, John Bright, Charles Bradlaugh, John Stuart Mill, Thorold Rogers, Henry Fawcett, Titus Salt, Thomas Perronet Thompson, Samuel Morley and Wilfrid Lawson. Taylor was appointed vice-president and often spoke at public meetings.

Bradlaugh, one of the greatest orators during this period, often appeared at meetings. Henry Snell commented: "Bradlaugh was already speaking when I arrived, and I remember, as clearly as though it were only yesterday, the immediate and compelling impression made upon me by that extraordinary man. I have never been so influenced by a human personality as I was by Charles Bradlaugh. The commanding strength, the massive head, the imposing stature, and the ringing eloquence of the man... I have seen strong men, under the storm of his passion, rise from their seats, and sometimes weep with emotion."

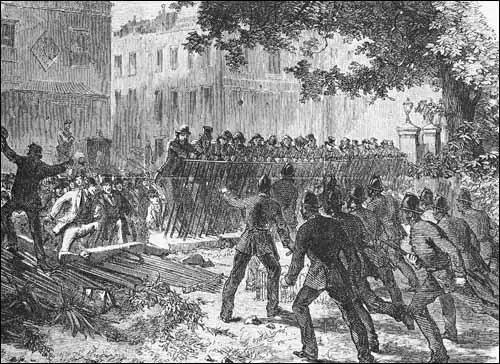

On 2nd July 1866 the Reform League organised "a great street procession and meeting, 30,000 strong, in support of the popular demand for household suffrage... the London press for days after the procession had marched through the principal streets of the fashionable West End, teemed with half-frightened references to its military aspects, good marching, admirable order, well closed column and complete discipline."

William Gladstone, the new leader of the Liberal Party, made it clear that he was in favour of increasing the number of people who could vote. Although the Conservative Party had opposed previous attempts to introduce parliamentary reform, they knew that if the Liberals returned to power, Gladstone was certain to try again. Gladstone was so popular that cheering crowds used to assemble outside his house.

Benjamin Disraeli, leader of the House of Commons, argued that the Conservatives were in danger of being seen as an anti-reform party. In 1867 Disraeli proposed a new Reform Act. Lord Cranborne (later Lord Salisbury) resigned in protest against this extension of democracy. However, as he explained this had nothing to do with democracy: "We do not live - and I trust it will never be the fate of this country to live - under a democracy."

Odger and other Reform League members had campaigned for adult suffrage but the government's proposals imposed strict restrictions on who could vote. At one meeting Odger declared that "nothing short of manhood suffrage would satisfy the working people". He went onto argue the vote would "prevent the labourer working for eight shillings a week."

In the House of Commons, Disraeli's proposals were supported by Gladstone and his followers and the measure was passed. The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832.

Several leaders of the Reform League unsuccessfully attempted to be elected to the House of Commons. This included George Howell in Aylesbury and William Cremer in Warwick. However, it was George Odger, who made the greatest effort. He attempted to stand at Chelsea in 1868 but failed to win the Liberal Party nomination. The same thing happen in Stafford in 1869 and Bristol 1870. He did stand in Southwark in 1870 but lost to the Conservative Party candidate by 304 votes.

The Spectator reported that he was the first working-class candidate to win more than 4,500 votes: "Nevertheless the result is that, for the first time, a member of the artizan class has polled upwards of 4,500 votes, and a considerably greater number of votes than a most wealthy, respectable, and benevolent member of the middle-class, who, in this borough, had every advantage that local connection could give him. That alone should be a pledge to members of the operative class that if they steadily persevere in their attempts to break down the class-feeling which at present excludes them from the House of Commons, they will soon succeed, and have quite sufficient success to secure to the House of Commons a very adequate infusion of the poorest, but by no means the least acute and energetic, class of the English people."

The novelist, Henry James, was dismissive of Odger's attempts to become a member of the House of Commons: "George Odger... was an English radical agitator, of humble origin, who had distinguished himself by a perverse desire to get into Parliament. He exercised, I believe, the useful profession of shoemaker, and he knocked in vain at the door that opens but to golden keys." However, Paul Foot has argued that Odger showed that it would not be long before working-class candidates would soon be elected to Parliament.

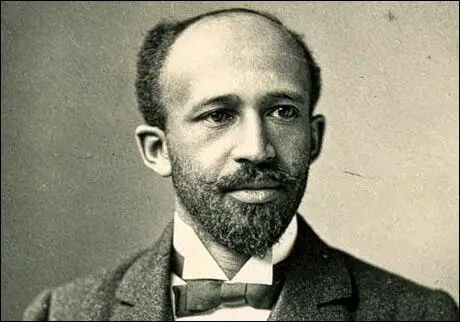

On this day in 1868 William Du Bois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. His father, Alfred Du Bois, left his mother, Mary Silvina Burghardt, soon after his birth. Paul Buhle has argued: "He grew up with an impoverished and crippled mother utterly dedicated to her only offspring. He had few bouts with racism as a child and graduated from high school a promising scholar."

When his mother died in 1884 Du Bois was forced to find work at a timekeeper in a local mill. Encouraged by Frank Hosmer, the principal of Great Barrington High School, Du Bois won a scholarship to Fisk University in Nashville. To help pay for his studies Du Bois taught in rural Tennessee during summer vacations. This gave him first-hand experience of Jim Crow laws and turned him into a civil rights activist.

After graduating in 1885 Du Bois spent two years at the University of Berlin before returning to the United States. Du Bois now had a strong interest in African American history and went to Harvard University to work on his dissertation, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade. In 1895 Du Bois became the first African American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard University.

In 1897 Du Bois began teaching economics and history at Clark Atlanta University. At this time he began campaigning against Jim Crow laws. In 1899 he wrote: "Such discrimination is morally wrong, politically dangerous, industrially wasteful, and socially silly. It is the duty of the whites to stop it, and to do so primarily for their own sakes. Industrial freedom of opportunity has by long experience been proven to be generally best for all. Moreover the cost of crime and pauperism, the growth of slums, and the pernicious influence of idleness and lewdness, cost the public far more than would the hurt to the feelings of a carpenter to work beside a black man, or a shop girl to start beside a darker mate. This does not contemplate the wholesale replacing of white workmen before Negroes out of sympathy or philanthropy; it does mean that talent should be rewarded, and aptness used in commerce and industry whether its owner be black or white."

In 1903 Du Bois published his ground-breaking The Souls of Black Folks. The journalist, Ray Stannard Baker, commented: "His economic studies of the Negro made for the United States Government and for the Atlanta University conference (which he organised) are works of sound scholarship and furnish the student with the best single source of accurate information regarding the Negro at present obtainable in this country. And no book gives a deeper insight into the inner life of the Negro, his struggles and his aspirations, than, The Souls of Black Folk."

The Souls of Black Folks included an attack on Booker T. Washington for not doing more in the campaign for African American civil rights. Du Bois own solution to this problem was to join forces with William Monroe Trotter to form the Niagara Movement in 1905. The group drew up a plan for aggressive action and demanded: manhood suffrage, equal economic and educational opportunities, an end to segregation and full civil rights.

William Du Bois began to read the works of Henry George, Jack London and John Spargo. He eventually became converted to socialism and in 1907 he wrote that "socialism was the one great hope of the Negro in America." He also became friendly with socialists such as Mary White Ovington and William English Walling.

The Niagara Movement had little impact on influencing those in power and in February, 1909, Du Bois joined with other campaigners for African American civil rights to form the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). Other members included Mary White Ovington, William English Walling, Josephine Ruffin, Mary Talbert, Mary Church Terrell, Inez Milholland, Jane Addams, Mary McLeod Bethune, George Henry White, Charles Edward Russell, John Dewey, William Dean Howells, Charles Darrow, Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, Fanny Garrison Villard, Oswald Garrison Villard and Ida Wells-Barnett.

In 1910 Du Bois returned to his attack on Booker T. Washington and his Tuskegee Institute movement and along with twenty-two other prominent African Americans signed a statement claiming: "We are compelled to point out that Mr. Washington's large financial responsibilities have made him dependent on the rich charitable public and that, for this reason, he has for years been compelled to tell, not the whole truth, but that part of it which certain powerful interests in America wish to appear as the whole truth."

The NAACP started its own magazine, Crisis, in November, 1910. The magazine was edited by Du Bois and contributors to the first issue included Oswald Garrison Villard and Charles Edward Russell. The magazine soon built up a large readership amongst black people and white sympathizers. By 1919 Crisis was selling 100,000 copies a month.

In Crisis Du Bois campaigned against lynching, Jim Crow laws, sexual inequality. He told his readers in October, 1911, that: "Every argument for Negro suffrage is an argument for women's suffrage; every argument for women's suffrage is an argument for Negro suffrage; both are great moments in democracy. There should be on the part of Negroes absolutely no hesitation whenever and wherever responsible human beings are without voice in their government." In 1912 he supported Eugene Debs, the Socialist Party candidate for president. He particularly admired the way that Debs refused to address segregated audiences in the South.

Du Bois supported United States involvement in the First World War. This caused him to break with the editors of other African American journals such as Chandler Owen, Philip Randolph and Hubert Harrison. Harrison was particularly upset by an article in The Crisis where he argued that: "Let, us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances and close our ranks."

Although Du Bois had originally been sympathetic to Black Nationalism, after the First World War he became highly critical of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Du Bois described the leader of the UNIA as "a lunatic or traitor" and Garvey retaliated by calling him a "white man's nigger".

In the early 1930s Du Bois began reading the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. In 1933 he began teaching a course entitled "Karl Marx and the Negro". According to Paul Buhle this created the "foundation for what could be described as the most important Marxist work on U.S. history, "Black Reconstruction" (1935)... by placing American slavery and emancipation at the center of the emergence of world capitalism and imperialism."

Du Bois continued to edit Crisis until 1934 when he became chairman of the Department of Sociology at Clark Atlanta University. He remained active in the NAACP and in 1945 was its representative at the San Francisco Conference which founded the United Nations. In the same year he also presided at the Pan-African Congress in Manchester.

Du Bois wrote a number of books on civil rights issues including The Philadelphia Negro (1899),The Souls of Black Folks (1903), John Brown (1909), The Negro (1915), The Gift of Black Folk (1924), Black Reconstruction in America (1935), Dusk of Dawn (1940) and Colour and Democracy (1945). A former member of the Socialist Party, Du Bois began to develop a Marxist interpretation of race relations in the 1930s.

A supporter of Henry Wallace for president in 1948, Du Bois unsuccessfully stood as a Progressive Party candidate for Senate in 1950. Du Bois, a victim of McCarthyism, was indicted as an agent for the Soviet Union in 1951. Although Du Bois was acquitted of the charge, the State Department denied him a passport until 1958.

Du Bois joined the Communist Party in 1961 with the words: "Capitalism cannot reform itself. Communism - the effort to give all men what they need and to ask of each the best they can contribute - this is the only way of human life."

At the age of 91 William Du Bois moved to Ghana where he became a naturalized citizen. He died on 27th August, 1963 and was honoured by a state funeral and buried in Accra.

On this day in 1892 Agnes Smedley, the daughter of a labourer, was born in Osgood, Missouri. Ten years later the family moved to the mining town of Trinidad, Colorado. Her father, Charles Smedley, deserted the family in 1903 and at the age of fourteen. Agnes now found work as a domestic servant in order to help to support her mother and her younger brothers and sisters.

In 1908 Smedley passed the New Mexico teacher's examination and although only sixteen years old, started work as a teacher in Terico. However, she was soon forced to return to Osgood to look after her younger brothers and sisters on the death of her mother, Sara Smedley. She later commented: "My mother, being frail, quiet, and gentle, died at the age of 38, of no particular disease, but from great weariness, loneliness of spirit, and unendurable suffering and hunger."

In September 1911 Smedley obtained a place at Tempe College. She immediately got involved in student politics and in March 1912 was appointed as editor of the campus newspaper. While at college she met Ernest Brundin who she married in 1912. The following year she moved to a teacher's college in San Diego.

Agnes Smedley became increasingly involved in politics and invited leading radicals such as Emma Goldman, Upton Sinclair and Eugene Debs to speak at the college. In 1916 she joined the Socialist Party of America. In December of that year she was dismissed from San Diego College for her socialist beliefs.

In 1917 Smedley and her husband divorced and she moved to New York City. In 1918 she was arrested and charged under the Espionage Act for attempting to stir up rebellion against British rule in India. Smedley was also charged with disseminating birth control information. While in prison Margaret Sanger and John Haynes Holmes led the campaign for her release.

In prison Smedley met two other radicals, Mollie Steimer and Kitty Marion. Steimer had been imprisoned for circulating leaflets in opposition to United States intervention in the Russian Civil War. Marion, who had just returned from England where she had been a leading member of the Women Social & Political Union, was serving a 30-day sentence for distributing pamphlets on birth control. She also became friends with Roger Baldwin who had been imprisoned for his public support of conscientious objectors in the First World War.

After being released from prison Smedley began writing for New York Call and the Birth Control Review, a journal run by Margaret Sanger. Smedley also published Cell Mates, a collection of stories inspired by women she met in prison. In March 1919 Smedley joined with Robert Morss Lovett, Norman Thomas and Roger Baldwin to form the Friends of Freedom for India. Although a close friend of Robert Minor, Smedley refused his invitation to join the American Communist Party.

In 1920 Smedley moved to Germany with the Indian revolutionary leader, Virendranath Chattopadhyaya and set up Berlin's first birth-control clinic. Although they did not marry, they lived as man and wife. During this period Smedley met Emma Goldman. She later recalled: "Agnes Smedley was a striking girl, an earnest and true rebel, who seemed to have no interest in life except the cause of the oppressed people in India. Chatto was intellectual and witty, but he impressed me as a somewhat crafty individual. He called himself an anarchist, though it was evident that it was Hindu nationalism to which he devoted himself entirely."

Agnes Smedley told a friend: "I've married an artist, revolutionary in a dozen different ways, a man of truly fine frenzy, nervous as a cat, always moving, never at rest, indefatigable energy a hundred fold more than I ever had, a thin man with much hair, a tongue like a razor and a brain like hell on fire. What a couple. I'm consumed into ashes. And he's always raking up the ashes and setting them on fire again. Suspicious as hell of every man near me - and of all men or women from America...I feel like a person living on the brink of a volcano crater. Yet it is awful to love a person who is a torture to you. And a fascinating person who loves you and won't hear of anything but your loving him and living right by his side through all eternity! We make a merry hell for each other, I assure you. He is rapidly growing grey, under my influence, I fear. And that tortures me."

In 1921 Smedley went to Russia but she was soon disillusioned with the lack of freedom in the country. She was especially upset to hear that old friends, Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, had been imprisoned for their political beliefs. She wrote to her friend, Florence Lennon: "The prisons are jammed with anarchists and syndicalists who fought in the revolution. Emma Goldman and Berkman are out only because of their international reputations. And they are under house arrest; they expect to go to prison any day, and may be there now for all I know. Any Communist who excuses such things is a scoundrel and a blaggard. Yet they do excuse it - and defend it. If I'm not expelled or locked up or something, I'll raise a small-sized hell. Everybody calls everybody a spy, secretly, in Russia, and everybody is under surveillance. You never feel safe."

Smedley wrote about events in Weimar Germany for The Nation and the New Masses. She was critical of both the Freikorps and the Communist Party. In one letter Smedley claimed that on occasions she "could see no difference between the two." While in Germany she became a close friend of the left-wing artist, Kathe Kollwitz.

In 1928 Smedley went to China and over the next few years wrote for the Manchester Guardian and the China Weekly Review. The following year her autobiographical novel, Daughter of Earth was published in the United States and Germany. It received good reviews and The Nation described it as "America's first feminist-proletarian novel".

In 1930 Smedley began a relationship with Richard Sorge, a German journalist working for the Frankfurter Zeitung. While in China Smedley spent a great deal of time with the communist forces and wrote several books including Chinese Destinies: Sketches of Present-Day China (1933), China's Red Army Marches (1934) and China Fights Back (1938).

Malcolm Cowley met Agnes Smedley for the first time in 1934: "Agnes Smedley is fanatical. Her hair grows thinly above an immense forehead. When she talks about people who betrayed the Chinese rebels, her mouth becomes a thin scar and her eyes bulge and glint with hatred. If this coal miner's daughter ever had urbanity, she would have lost it forever in Shanghai when her comrades were dragged off one by one for execution. .This evening I'm drawing back. I don't wait to hear Agnes Smedley give her speech, which will be more convincing than the others, as if each phrase of it were dyed in the blood of her Chinese friends."

Smedley also became close friends with Joseph Stilwell and Evans Carlson. Stilwell was commander of the United States Army in China whereas Carson was President Roosevelt's personal adviser in the country. While in China Smedley reported on the Japanese Army invasion in 1937 for the Manchester Guardian.

Freda Utley met Smedley in 1938: "Agnes was one of the few people of whom one can truly say that her character had given beauty to her face, which was both boyish and feminine, rugged and yet attractive. She was one of the few spiritually great people I have ever met, with that burning sympathy for the misery and wrongs of mankind which some of the saints and some of the revolutionaries have possessed. For her the wounded soldiers of China, the starving peasants and the overworked coolies, were brothers in a real sense. She was acutely, vividly aware of their misery and could not rest for trying to alleviate it. Unlike those doctrinaire revolutionaries who love the masses in the abstract but are cold to the sufferings of individuals, Agnes Smedley spent much of her time, energy, and scant earnings in helping a multitude of individuals."

Smedley returned to the United States in May 1941 and went on a nationwide lecture tour where she gave talks on her experiences in China. Her book, Battle Hymn of China, was published in 1943, and is considered to be one of the best works of war reporting that came out of the Second World War.

On a tour of the Deep South in 1942 she was appalled by the Jim Crow laws. Smedley caused a stir when she gave an interview to the Los Angeles Tribune where she complained "we can't treat men like dogs and expect them to act like men." As a result of this outburst, J. Edgar Hoover instructed FBI agents to investigate her political past. John S. Gibson of Georgia raised the issue of Smedley's comments in the House of Representatives and accused her of being the "author of many books which portray the glory of the Communist Party."

The FBI interviewed Whittaker Chambers in May 1945. Chambers, a former communist spy, claimed wrongly that Smedley was a secret member of the Communist Party of the United States. This was untrue, in fact Smedley had been a strong opponent of the party since the 1920s. As a libertarian socialist she had appalled by the way the party had supported the repressive policies of Joseph Stalin and his communist government in the Soviet Union.

Smedley continued to lecture on world politics. These speeches were monitored by the FBI and the agents became increasingly concerned with Smedley's attacks on the US government's support for totalitarian regimes. In July 1946 the FBI put Smedley on its Security Watch List.

In 1947 the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), chaired by J. Parnell Thomas, began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. The HUAC interviewed 41 people who were working in Hollywood. These people attended voluntarily and became known as "friendly witnesses". During their interviews they named nineteen people who they accused of holding left-wing views.

One of those named, Bertolt Brecht, an emigrant playwright, gave evidence and then left for East Germany. Ten others: Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Samuel Ornitz, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson and Alvah Bessie refused to answer any questions.

Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The House of Un-American Activities Committee and the courts during appeals disagreed and all were found guilty of contempt of congress and each was sentenced to between six and twelve months in prison. Smedley responded to these events by helping to form the Progressive Citizens of America, a civil rights group that was committed to defending Hollywood writers, directors and producers who had been named as communists or communist sympathizers by the HUAC.

On 1st January 1948, the Chicago Tribune carried a story claiming that Smedley was being investigated as part of communist espionage ring based in Japan during the 1930s. The article claimed that Smedley was working with the German journalist, Richard Sorge, who was spying on the Japanese government on behalf of the Soviet Union.

Sorge was indeed a spy and had been the first to supply evidence to the west about the proposed attack on Pearl Harbour. Sorge had been arrested by the Japanese authorities in October 1941 and was executed three years later. Although Smedley had been a close friend of Sorge when he had been in China in 1930, she was not involved in his spying activities and despite the article no charges were ever brought against Smedley.

Harold Ickes, secretary of the interior for ten years under Franklin D. Roosevelt, bravely wrote an article in the New York Post, arguing that there was no truth in the claim that the United States government knew that Smedley was a communist spy. However, America was now entering the period of McCarthyism and this was the first of many smear stories circulated about Smedley.

Depressed by the smear stories and the early deaths of her close friends, Joseph Stilwell and Evans Carlson, Agnes Smedley decided to move to England in November 1949. Agnes Smedley went to live in Oxford but was now in poor health and she died of acute circulatory failure on 6th May, 1950.

On this day in 1936 William Adamson died. William, the son of James Armstrong Adamson, a coalminer, and Flora Cunningham, was born in Dunfermline on 2nd April 1863. He was educated at a local dame school but at the age of eleven he left to work as a miner in Fife.

Adamson married Christine Marshall, a winder in a damask factory, on 25th February 1887. Over the next few years the couple had two sons and two daughters.

Adamson joined the National Union of Mineworkers but as David W. Howell has pointed out: "The 1870s were a decade of vigorous trade-union activity in the Scottish coalfields, but, with the exception of Fife, union organization proved brittle. The Fife and Kinross Miners' Association survived some difficult periods, not least because the coal owners, sensitive to the pressures of the export trade, preferred negotiation to conflict." Adamson first became active in the union as a branch delegate and became vice-president in 1894, assistant secretary in 1902, and general secretary, in 1908.

Like most trade union leaders during this period, Adamson was initially a member of the Liberal Party. However, Adamson eventually joined the Labour Party and in 1905 was elected to Dunfermline Council. In the 1910 General Election he was elected to the House of Commons.

On 5th August, 1914, the parliamentary party voted to support the government's request for war credits of £100,000,000. Ramsay MacDonald immediately resigned the chairmanship. He wrote in his diary: "I saw it was no use remaining as the Party was divided and nothing but futility could result. The Chairmanship was impossible. The men were not working, were not pulling together, there was enough jealously to spoil good feeling. The Party was no party in reality. It was sad, but glad to get out of harness." Arthur Henderson, once again, became the leader of the party.

Adamson was a strong supporter of Britain's involvement in the First World War and although he was at first unhappy about military conscription and voted against the second reading of the Military Service Bill in January 1916. Arthur Henderson became the first member of the Labour Party to hold a Cabinet post when Herbert Asquith invited him to join his coalition government.

After the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II in Russia, socialists in Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, United States and Italy called for a conference in a neutral country to see if the First World War could be brought to an end. Eventually, it was announced that the Stockholm Conference would take place in July 1917. Arthur Henderson was sent by David Lloyd-George to speak to Alexander Kerensky, the leader of the Provisional Government in Russia.

At a conference of the Labour Party held in London on 10th August, 1917, Henderson made a statement recommending that the Russian invitation to the Stockholm Conference should be accepted. Delegates voted 1,846,000 to 550,000 in favour of the proposal and it was decided to send Henderson and Ramsay MacDonald to the peace conference. However, under pressure from President Woodrow Wilson, the British government had changed his mind about the wisdom of the conference and refused to allow delegates to travel to Stockholm. As a result of this decision, Henderson resigned from the government and as chairman of the Labour Party.

David W. Howell has argued: "His experience as effectively party leader in the Commons was unhappy. Many felt that he lacked the necessary qualities." Beatrice Webb commented in her diary: "He has neither wit, fervour nor intellect; he is most decidedly not a leader, not even like Henderson, a manager of men."

In the 1918 General Election, a large number of the Labour leaders lost their seats. This included Arthur Henderson, Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, George Lansbury and Fred Jowett. Adamson held the post until February 1921 when he was replaced by John R. Clynes. Snowden commented: "Clynes had considerable qualifications for Parliamentary leadership. He was an exceptionally able speaker, a keen and incisive debater, had wide experience of industrial questions, and a good knowledge of general political issues. In the Labour Party Conferences when the platform got into difficulties with the delegates, Mr. Clynes was usually put up to calm the storm."

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". Ramsay MacDonald agreed to head a minority government, and therefore became the first member of the party to become Prime Minister. MacDonald appointed Adamson as Secretary of State for Scotland. However, he only held the post for eleven months as the Labour Party lost power in November 1924.

In the 1929 General Election the Labour Party won 288 seats, making it the largest party in the House of Commons. MacDonald became Prime Minister again, but as before, he still had to rely on the support of the Liberals to hold onto power. Once again MacDonald appointed Adamson as Secretary of State for Scotland.

The election of the Labour Government in 1929 coincided with an economic depression and Ramsay MacDonald was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. MacDonald asked Sir George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problem. When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it suggested that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. MacDonald, and his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, accepted the report but when the matter was discussed by the Cabinet, the majority voted against the measures suggested by Sir George May.

Ramsay MacDonald was angry that his Cabinet had voted against him and decided to resign. When he saw George V that night, he was persuaded to head a new coalition government that would include Conservative and Liberal leaders as well as Labour ministers. Most of the Labour Cabinet totally rejected the idea and only three, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey agreed to join the new government.

MacDonald was determined to continue and his National Government introduced the measures that had been rejected by the previous Labour Cabinet. Labour MPs were furious with what had happened and MacDonald was expelled from the Labour Party. In October, MacDonald called an election. The 1931 General Election was a disaster for the party with only 46 members winning their seats. Adamson also lost his seat in West Fife.

in 1935 General Election Adamson was defeated by his long-term rival, Willie Gallacher of the Communist Party of Great Britain, at West Fife, by 593 votes.