On this day on 20th July

On this day in 1591 Anne Hutchinson, the daughter of a clergyman, was born in Lincolnshire, England. A Puritan, Hutchinson emigrated with her husband to America in 1634.

Hutchinson settled in Massachusetts Bay, where she soon obtained a following as a preacher. Hutchinson began to claim that good conduct could be a sign of salvation and affirmed that the Holy Spirit in the hearts of true believers relieved them of responsibility to obey the laws of God. She also criticised New England ministers for deluding their congregations into the false assumption that good deeds would get them into heaven.

Complaints were made about Hutchinson's teachings and John Winthrop, the governor of Massachusetts, called her to appear before the authorities. During her cross-examination she claimed that she had received a revelation from God. To the Puritan authorities this was blasphemy and she was banished from the community.

Anne Hutchinson joined Roger Williams and his colony on Rhode Island. The colony was a haven of religious toleration and admitted Jews and Quakers and other religious dissenters.

After the death of her husband in 1642, Hutchinson moved to a new settlement in Pelham Bay. The following year in August, Anne Hutchinson and fourteen members of her family were murdered by Native Americans in the area.

On this day in 1891 Ada Brown was born in Raunds, Northamptonshire. As a young woman she joined the West London Mission. As a friend later argued, "her motive was religious, but she had soon added a social purpose to it."

In 1897 she transferred to the Bermondsey Settlement where she was the leader of the Mothers' Meeting and had responsibility for the Girls' Club. Fenner Brockway has pointed out: "The girls were rag-sorters, wood-choppers, tin-smiths, rough and tough, sometimes reacting against the drabness of their existence by indulging in wild excesses, sometimes arriving drunk at the Club. Ada Brown's gracious personality had a remarkable effect upon many of these girls: they came under its influence, their characters began to change and, despite their surroundings, a gentleness and love of beauty came into their lives.

While working at the settlement she met and fell in love with Alfred Salter, who was a student at Guy's Hospital. He converted her to socialism and she encouraged him to become a Christian. They both joined the Peckham branch of the Society of Friends. They both decided they should dedicate their lives to helping the poor. On 6th July 1899 Alfred wrote to Ada: "I have been paying numerous visits to derelict families all the afternoon and evening. Several of the homes I have just been into have made me feel aghast at my helplessness and powerlessness to lift their occupants out of their existing poverty and squalor. Oh, the cruelty and wickedness of our society today! - to thrust down these people by means of low wages and chronic unemployment into hopeless despair, and then to leave them in that condition with no organised or conscious effort to rehabilitate them.... You and I feel that we have the same mission in life and the same consciousness of the ends, objects and consequences of that mission. We are living and working for the same goal - to make the world, and in particular, this corner of the world, happier and holier for our joint lives."

Alfred and Ada Salter decided to devote their lives to the people of Bermondsey and he established a general medical practice in the area. Salter rented out a shop on Jamaica Road and turned it into a surgery. They were married at Raunds on 22nd August 1900. Fenner Brockway has argued: "In Jamaica Road they began the partnership which was to bring something little short of a revolution to Bermondsey and its people."

Salter's takings during the first week amounted to 12s. 6d. As one source points out: "This did not last long, however; within a few weeks his problem became too many clients. It was not only his low charges which attracted patients: it was the treatment he gave and the way in which he gave it, it was the energy with which he insisted on beds in hospitals for urgent cases." Salter was so successful that he soon needed to recruit four other doctors to the surgery. They were chosen because they shared his basic values of Christian Socialism. Salter ran the surgery as a local cooperative and the five doctors shared their takings equally.

Ada Salter was active in the Liberal Party. She also joined the Rotherhithe Women's Association and became its president. On 5th June, 1902, Ada gave birth to Joyce. Four years later they rented out a house in Storks Road. According to Fenner Brockway it "was a grimy three-storied building, with a basement and yard, overhung by a large factory." A friend, Albert Dawson, wrote: "Dr. Salter is not a reposeful man; he is too high-spirited and vigorous, and lives at the top of his form, but the gentle sweetness and serenity of Mrs. Salter balance her husband's energy and strength."

Ada and Alfred Salter gradually grew disillusioned with the Liberal Party's lack of radicalism and in May 1908 they joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP).This was partly because of the leadership of James Keir Hardie and his policies of "the school-feeding of hungry children, for old-age pensions, for the maintenance of the unemployed." They joined with twelve friends to establish a ILP branch in Bermondsey.

In June 1910, Ada's daughter, Joyce, caught scarlet fever. She became seriously ill and was admitted to the South-Western Fever Hospital. Joyce was adored in Bermondsey, everyone calling her "our little ray of sunshine". There were so many enquiries that bulletins had to be placed at regular intervals on the front door of their home. Unfortunately she died and according to their friend, Fenner Brockway: "It needed all their faith to live through this test. Ada's sadness never quite left her; it was in her eyes and in her expression all through the years. Alfred changed from the boisterously cheerful crusader to a man who seemed constantly in the presence of sorrow: months passed before he smiled and it was years before the gay, bubbling laughter returned. Joyce's portrait, on the mantelpiece in his study, was decorated by Ada with flowers or ivy every day: right to the end of their working lives this practice was observed. The sense of loss was intensified as the years passed by the disappointment that Joyce remained their only child."

In November 1910, the Independent Labour Party nominated seven candidates for the Borough Council elections. However, only one, Ada Salter, was elected. She therefore became the first woman councillor in London. That night the ILP had a party in Bermondsey where they discussed their plans for the future. Alfred Salter said: "We'll pull down three-quarters of Bermondsey and build a garden city in its place."

The Bermondsey ILP arranged for a series of Thursday evening lectures. This included visits by Margaret MacMillan, Bruce Glasier, Katherine Glasier, Charlotte Despard, G. D. H. Cole, Clement Attlee, Herbert Morrison, Jessie Stephen, George Lansbury, William Anderson and H. H. Slesser.

Ada Salter was active in the campaign for women's suffrage. In 1906 Ada Salter helped to establish the Women's Labour League. It was affiliated to the Labour Party. Other members included Margaret MacDonald, Margaret Bondfield, Katherine Glasier, Charlotte Despard, Mary Gawthorpe, Mary Macarthur and Marion Phillips. Ada supported the non-violent Women's Freedom League as she rejected the tactics of the Women's Social and Political Union. .

Ada Salter remained active in the ILP and in 1913 was re-elected to the Bermondsey County Council. However, Alfred Salter and the other 13 ILP candidates were defeated. Ada campaigned to convert Bermondsey into a Garden City. On her initiative a Beautification Committee was appointed.

In the 1922 General Election Ada's husband, Alfred Salter, was elected to represent Bermondsey West in the House of Commons. The Labour Party also had the largest number of seats on the Bermondsey Borough. Ada now became London's first Mayor. As a socialist she declined to wear Mayoral robes or the chain of office.

With a Labour majority on the council, Ada could now push on with her plans to improve the look of Bermondsey. A Borough Gardens Superintendent was employed and ordered to plant elms, populars, planes and acacias in the streets of Bermondsey. Later he added birch, ash, yew and wild cherry.

The new Labour council also launched a campaign to improve public health in Bermondsey. Special films were prepared and were shown to large crowds in the open air and pamphlets were distributed throughout the borough. A systematic house-to-house inspection was conducted to seek out conditions dangerous to health. Premises where food was sold were constantly examined and samples of foods were taken away for analysis.

The people of Bermondsey welcomed the actions taken by the local council. In the 1925 elections, it established a national record when every seat on the Borough Council and the Board of Guardians returned Labour members. The parliamentary seat and the two London County Council seats were also held by the party.

When the Labour Party took office in 1922 the death-rate was 16.7 per 1,000. By 1927 it had fallen to 12.9. In 1922 the number of new cases of tuberculosis was 413. In 1927 it was 294. Deaths from the disease fell from 206 to 175. Alfred Salter claimed " Though Bermondsey is an overcrowded industrial area, with few amenities and a poor population living under great residential and economic disadvantages, yet if the death rate continues to diminish at the present rate, the borough will be entitled in a few years to be regarded as one of Britain's health resorts. Day in, day out, year in, year out, this wonderful preventive work, scientifically organised and directed by trained brains, is going on like clockwork. The Labour majority in the Council intend to employ any and every means to stamp out preventable illness."

Alfred Salter resigned from Bermondsey Borough Council in 1931, but she remained and continued her struggle to turn Bermondsey into a Garden City. The journalist, Fenner Brockway, wrote about the progress that had been made by 1937: "By this time Bermondsey's trees and flowers were famous. Travelling on the Southern Railway by the long viaduct which crosses the borough passengers noted with wonder the avenues of green between the crowded buildings, the beds of tulips or dahlias in the gaps between the houses, the climbing roses on the balconies of the tenements. Films of the streets, gardens and churchyards were shown all over the world and some American visitors included them with Westminster Abbey and the Tower of London in the sights of London." An article in The Observer commented that "outside the Royal Parks it would be, difficult to find anywhere such masses of colour."

In 1937 Ada Salter and her close friend, Eveline Lowe, were once again elected to both the London County Council and the Bermondsey Borough Council. Every seat was won by the Labour Party and after the elections the Conservative Party Association closed its offices in Bermondsey.

Ada gave an interview to The Evening News in July, 1939, about her marriage and political work. "I don't know anything about medicine and I've never thought of standing for Parliament, but then he doesn't garden, to even things up. One thing we don't share is a study. He has such a stock of books and papers that when I have letters to write I borrow his secretary's room... I don't know what it would be like to have two politicians in the home who take opposite views, but we two, who have the same opinions, but different fields of administration, find it very satisfactory indeed."

Ada Salter died on 5th December, 1942. Alfred Salter wrote a month later: "The loneliness grows deeper and has not lessened in the slightest with the lapse of time. Sometimes it is almost unbearable, but I have to learn to bear it."

On this day in 1870 Margaret Ethel Gladstone was born on 20th July, 1870. Her father, John Hall Gladstone, was one of the founders of the Youth Men's Christian Association (YMCA) and was Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution. He was also a member of the Liberal Party and just before Margaret's birth had failed to win York in the 1868 General Election. Her mother, Margaret Thompson King, was closely related to the famous scientist William Thompson. Margaret's mother died soon after she was born.

Margaret Gladstone was educated at the Doreck College for Girls in Bayswater and the women's department of King's College and studied political economy under Millicent Fawcett. According to David Marquand: "Margaret was an attractive, light-hearted girl; but had all the stubborn determination, as well as the intense religious feeling of her puritan ancestors. She had no respect for middle-class convention, as she was certainly not prepared to wait meekly in her father's house till someone came to marry her." In May 1889 she became a Sunday School teacher at St. Mary Abbots Church in Kensington. She also found work as secretary of the Hoxton and Haggerston Nursing Association. In 1893 she became a volunteer worker for the Charity Organization Society in Hoxton.

Margaret's experiences of working with the poor in London resulted in her questioning the merits of capitalism. At first she was influenced by Christian Socialists, such as Frederick Denison Maurice and Charles Kingsley. After hearing Ben Tillett speak at a Unitarian Society meeting she became a socialist. She also joined the Fabian Society and in 1894 became a member of the Women's Industrial Council. Other members included Clementina Black, Eleanor Marx, Hilda Martindale, Charlotte Despard, Evelyn Sharp, Mary Macarthur, Cicely Corbett Fisher, Lily Montagu and Margery Corbett-Ashby.

May 1895 she saw Ramsay MacDonald addressing an audience during his campaign to win the Southampton seat in the 1895 General Election. She noted that his red tie and curly hair made him look "horribly affected". However, she sent him a £1 contribution to his election fund. A few days later she became one of his campaign workers. MacDonald, along with the other twenty-seven Independent Labour Party candidates, was defeated and overall, the party won only 44,325 votes.

The following year they began meeting at the Socialist Club in St. Bride Street and at the British Museum, where they both had readers' tickets. In April 1896 she joined the ILP. In a letter she admitted that before she met him she had been terribly lonely: "But when I think how lonely you have been I want with all my heart to make up to you one tiny little bit for that. I have been lonely too - I have envied the veriest drunken tramps I have seen dragging about the streets if they were man and woman because they had each other... This is truly a love letter: I don't know when I shall show it you: it may be that I never shall. But I shall never forget that I have had the blessing of writing it."

They decided to get married and in a letter she wrote to MacDonald on 15th June, 1896 about her situation: "My financial prospects I am very hazy about, but I know I shall have a comfortable income. At present I get £80 allowance (besides board & lodging, travelling and postage); my married sister has, I think about £500 all together. When my father dies we shall each have our full share, and I suppose mine will be some hundreds a year... My ideal would be to live a simple life among the working people, spending on myself whatever seemed to keep me in best efficiency, and giving the rest to public purposes, especially Socialist propaganda of various kinds."

After they were married in 1897, Margaret MacDonald was able to finance her husband's political career from her private income. The couple travelled a great deal in the late 1890s and this gave MacDonald the opportunity to meet socialist leaders in other countries and helped him develop an good understanding of foreign affairs.

Bruce Glasier wrote: "Margaret MacDonald might easily have been taken for the nursemaid in a small middle-class family. Her naivety, simplicity, unselfishness and amazing capacity for organisation and helpful work made her one of the best liked women I have known. There was little in her to attract men, as men, but everything to attract women and men who had enthusiasm for public work." The marriage was a very happy one, and over the next few years they had six children, Alister (1898), Malcolm (1901), Ishbel (1903), David (1904), Joan (1908) and Shelia (1910).

Keir Hardie, the leader of the Independent Labour Party and George Bernard Shaw of the Fabian Society, believed that for socialists to win seats in parliamentary elections, it would be necessary to form a new party made up of various left-wing groups. On 27th February 1900, representatives of all the socialist groups in Britain met with trade union leaders at the Congregational Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street. After a debate the 129 delegates decided to pass Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." To make this possible the Conference established a Labour Representation Committee (LRC). This committee included two members from the Independent Labour Party, two from the Social Democratic Federation, one member of the Fabian Society, and seven trade unionists.

Ramsay MacDonald was chosen as the secretary of the LRC. One reason for this was Margaret's income meant that he did not have to be paid a salary. The LRC put up fifteen candidates in the 1900 General Election and between them they won 62,698 votes. Two of the candidates, Keir Hardie and Richard Bell won seats in the House of Commons.

Margaret MacDonald was active in the campaign for women's suffrage. In 1906 she helped to establish the Women's Labour League, which was established to encourage women to become involved in the Labour Party and to seek improvements in the work and family lives of working-class women. Other members included Ada Salter, Margaret Bondfield, Katherine Glasier, Charlotte Despard, Mary Gawthorpe, Mary Macarthur and Marion Phillips. Ada supported the non-violent Women's Freedom League as she rejected the tactics of the Women Social & Political Union.

According to David Marquand: "Although she coped efficiently with an intimidating mass of public work, there was nothing intimidating about her personality. Her clothes were the despair of her friends, and slightly shocked her much more conventional husband." Grace Paton. who worked for the MacDonalds, later recalled: "They were very untidy - he wasn't, I think he wanted to be tidy, but she never. There was a great big armchair, an enormous one full of papers; and I think she kept all the clothes she ever had, because clearing up was rather difficult."

Margaret MacDonald remained an active member of the Women's Industrial Council. According to her biographer, June Hannam: "She was secretary of the council's legal and statistical committee, and a member of its investigations and education committees.... In the early 1900s Margaret MacDonald drew attention to the needs of unemployed women. Through her efforts the central unemployment board of London appointed a special women's work committee which established municipal workrooms for clothing workers. She helped to organize a march of unemployed women in Whitehall in 1905 and in 1907 initiated a national conference on the unemployment of women dependent on their own earnings... Despite her long-standing interest in working conditions, and her own attempts to combine motherhood and public activities, she believed that women's most important role was in the home and she was consistent in her opposition to married women's paid employment."

Arthur Henderson did not have the full-support of the party and in 1910 he decided to retire as chairman. Ramsay MacDonald was expected to become the new leader but in February the family suffered two shattering emotional blows. On 3rd February his youngest son, David, died of diphtheria. Eight days later Ramsay's mother also died. It was therefore decided that George Barnes should become chairman instead. A few months later Barnes wrote to MacDonald saying he did not want the chairmanship and was "only holding the fort". He continued, "I should say it is yours anytime".

The 1910 General Election saw 40 Labour MPs elected to the House of Commons. Two months later, on 6th February, 1911, George Barnes sent a letter to the Labour Party announcing that he intended to resign as chairman. At the next meeting of MPs, Ramsay MacDonald was elected unopposed to replace Barnes. Arthur Henderson now became secretary. According to Philip Snowden, a bargain had been struck at the party conference the previous month, whereby MacDonald was to resign the secretaryship in Henderson's favour, in return for becoming chairman."

On 4th July, 1910, Ramsay MacDonald wrote: "My little David's birthday... Sometimes I feel like a lone dog in the desert howling from pain of heart. Constantly since he died my little boy has been my companion. He comes and sits with me especially on my railway journey and I feel his little warm hand in mine. That awful morning when I was awakened by the telephone bell, and everything within me shrunk in fear for I knew I was summoned to see him die, comes back often too."

On 20th July 1911, Ramsay MacDonald arranged for Margaret MacDonald to meet William Du Bois in the House of Commons. He later explained: "A little after noon she joined me at the House of Commons with one whom she had desired to meet ever since she had read his book on the negro, Professor Du Bois; that afternoon we went to country for a weekend rest. She complained of being stiff, and jokingly showed me the finger carrying her marriage and engagement rings. It was badly swollen and discoloured, and I expressed concern. She laughed away my fears... On Saturday she was so stiff that she could not do her hair, and she was greatly amused by my attempts to help her. On Sunday she had to admit that she was ill and we returned to town. Then she took to bed."

According to Bruce Glasier she was treated by Dr. Thomas Barlow, who told MacDonald that he could not save her. "When she heard that she was doomed, she was silent, and said with a slight tremble in her voice, I am very sorry to leave you - you and the children - alone. She never wept - never to the end. She asked if the children could be brought to see her. When the boys were brought to her, she spoke to each one separately. To the boys she said, I wish you only to remember one wish of your mother's - never marry except for love."

Margaret MacDonald died on 8th September 1911, at her home, Lincoln's Inn Fields, from blood poisoning due to an internal ulcer. Her body was cremated at Golders Green on 12th September and the ashes were buried in Spynie Churchyard, a few miles from Lossiemouth. Her son, Malcolm MacDonald, later recalled: "At the time of my mother's death... my father's grief was absolutely horrifying to see. Her illness and her death had a terrible effect on him of grief; he was distracted; he was in tears a lot of time when he spoke to us... it was almost frightening to a youngster like myself."

Ramsay MacDonald wrote a short memoir of his wife, which was privately printed and circulated to friends. He told Katharine Bruce Glasier: "I felt myself hearing her approval of it, so much so that I seemed to see her hand on your shoulder as you wrote - and grew foolishly weakly blind with tears for the pain that was there."

On this day in 1889 John Reith was born Stonehaven, Scotland. His father, Dr. George Reith, was a minister of the United Free Church of Scotland. After being educated at Glasgow Academy Reith served an engineering apprenticeship in London.

On the outbreak of the First World War Reith joined the British Army. He was appointed as a Transport Officer and sent to France in November 1914. He was soon in conflict with his Commanding Officer, Robert Douglas and the Adjutant, William Croft. He later recalled: "No bath water boiled more vehemently than did my indignation." As his biographer commented: "It was a lifelong characteristic of John Reith that he could not get on with other men, especially those in authority."

Colonel Robert Douglas eventually told Reith that he was being sent home. Before this could be arranged he drank water from a farm well and became violently ill. Suffering from dysentery he was sent to hospital in England.

In September 1915 Lieutenant Reith joined the Highland Field Company Royal Engineers. He arrived on the Western Front during the major offensive at Loos. His first task was to mark out a support trench seventy yards behind the new front line. He later wrote in his autobiography, Wearing Spurs: "I had never witnessed such sights before; this was indeed a battlefield. I had seen dead men and dead horses but never in these numbers."

On 7th October 1915 Reith was sent to repair a section of a front-line trench destroyed by a mine. While carrying out the work he was shot in the head by a German sniper. Some of the bone in his face had been shot away and he lost a lot of blood but he was not dangerously wounded.

Reith was sent to Scotland to recover and after he was released from hospital he joined the staff of a munitions factory in Gretna. In March 1916 he was sent by the Ministry of Munitions to the United States to buy rifles. On his return he was transferred to the Royal Marine Engineers.

At the end of the war, Reith returned to Glasgow to work in engineering. After working briefly for the Conservative Party, in December 1922 was appointed general manager of the British Broadcasting Company, an organization was set up by a group of executives from radio manufacturers.

During the 1926 General Strike Reith came into conflict with the government when he attempted to allow all parties the opportunity to comment on the radio. Eventually, he gave in to the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, and imposed strict censorship and even turned down a direct request from the Labour Party leader Ramsay MacDonald to speak to the country.

In 1927 the government decided to establish the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) as a broadcasting monopoly operated by a board of governors and director general. The BBC was funded by a licence fee at a rate set by parliament. The fee was paid by all owners of radio sets. The BBC therefore became the world's first public-service broadcasting organization. Unlike in the United States, advertising on radio was banned.

John Reith was appointed director-general of the BBC. Reith had a mission to educate and improve the audience and under his leadership the BBC developed a reputation for serious programmes. Reith also insisted that all radio announcers wore dinner jackets while they were on the air. In the 1930s the BBC began to introduce more sport and light entertainment on the radio.

It was later revealled that Reith was a great admirer of Adolf Hitler. On 9th March 1933 Reith wrote "I am certain that the Nazis will clean things up and put Germany on the way to being a real power in Europe again.... They are being ruthless and most determined". Later, when Prague was occupied, Reith wrote: "Hitler continues his magnificent efficiency."

Reith was also accused of acting like the Nazi Germany government. In the House of Commons, the Labour MP, Hastings Lees-Smith, argued: "The BBC is an autocracy which has outgrown the original autocrat... It has become despotism in decay... the nearest thing in this country to Nazi government that can be shown... If I talk to any employee of the Corporation, I am made to feel like a conspirator."

The BBC began the world's first regular television service in 1936. Two years later Reith was forced to resign his post at the BBC by Neville Chamberlain. Reith now became chairman of Imperial Airways.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Reith was invited to join the government. Elected to the House of Commons for Southampton, Reith was appointed as Minister of Information in January 1940. When Winston Churchill replaced Chamberlain in May 1940 he appointed Reith to the post of Minister of Transport. Five months later he was given a peerage and given the job of Minister of Works and Buildings. However, the two men did not get on and Churchill eventually dismissed him from his government post as being too difficult to work with. He was however, granted a peerage and he became Baron Reith of Stonehaven.

After the war Reith served as chairman of the Commonwealth Telecommunications Board (1946-50). He also wrote two volumes of autobiography, Into the Wind (1949) and Wearing Spurs (1966).

The Independent Television Authority was created on 30 July 1954 ending the BBC's existing broadcasting monopoly. In the House of Lords Lord Reith complained: "Somebody introduced Christianity into England and somebody introduced smallpox, bubonic plague and the Black Death. Somebody is minded now to introduce sponsored broadcasting ... Need we be ashamed of moral values, or of intellectual and ethical objectives? It is these that are here and now at stake."

John Reith died on 16th June 1971.

On this day in 1915 Harold Macmillan wrote a letter to his mother, Helen Macmillan: "They have big hearts, these soldiers, and it is a very pathetic task to have to read all their letters home. Some of the older men, with wives and families who write every day, have in their style a wonderful simplicity which is almost great literature.... And then there comes occasionally a grim sentence or two, which reveals in a flash a sordid family drama."

Twelve and a half million letters were sent to the Western Front every week. In 1914 the Postal Section of the Royal Engineers had a staff of 250 men. By 1918 the Army Postal Service employed 4,000 soldiers. Letters only took two or three days to arrive from Britain. Even soldiers in the front line trenches received daily deliveries of letters.

Soldiers were also encouraged to write letters to friends and family in Britain. Most men decided it would be better to conceal the horrors of the trench warfare. As a result of the Defence of the Realm Act that was passed in 1914, all letters that the men wrote should have been read and censored by junior officers.

Some officers could not bring themselves to read their men's letters and these arrived in Britain unaltered. For example, Lieutenant John Reith later admitted in his autobiography, Wearing Spurs (1966): "I did my best to take an interest in the members of my platoon personally. In manual exercises and in extended order drill in a field I could take none; and they knew it. I was supposed to censor their letters home, but I informed them that they were on their honour not to say things they should not say, and I handed over the censor's stamp to the sergeant."

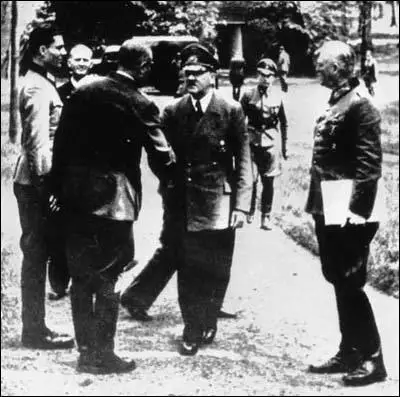

On this day in 1944 the July Plot to kill Adolf Hitler took place. On this day Claus von Stauffenberg and Werner von Haeften left Berlin to meet with Hitler at the Wolf' Lair. After a two-hour flight from Berlin, they landed at Rastenburg at 10.15. Stauffenberg had a briefing with Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of Armed Forces High Commandat, at 11.30, with the meeting with Hitler due to take place at 12.30. As soon as the meeting was over, Stauffenberg, met up with Haeften, who was carrying the two bombs in his briefcase. They then went into the toilet to set the time-fuses in the bombs. They only had time to prepare one bomb when they were interrupted by a junior officer who told them that the meeting with Hitler was about to start. Stauffenberg then made the fatal decision to place one of the bombs in his briefcase. "Had the second device, even without the charge being set, been placed in Stauffenberg's bag alone with the first, it would have been detonated by the explosion, more than doubling the effect. Almost certainly, in such an event, no one would have survived."

When he entered the wooden briefing hut, twenty-four senior officers were in assembled around a huge map table on two heavy oak supports. Stauffenberg had to elbow his way forward a little in order to get near enough to the table and he had to place the briefcase so that it was in no one's way. Despite all his efforts, however, he could only get to the right-hand corner of the table. After a few minutes, Stauffenberg excused himself, saying that he had to take a telephone call from Berlin. There was continual coming and going during the briefing conferences and this did not raise any suspicions.

Stauffenberg and Haeften went straight to a building about 200 hundred yards away consisting of bunkers and reinforced huts. Shortly afterwards, according to eyewitnesses: "A deafening crack shattered the midday quiet, and a bluish-yellow flame rocketed skyward... and a dark plume of smoke rose and hung in the air over the wreckage of the briefing barracks. Shards of glass, wood, and fiberboard swirled about, and scorched pieces of paper and insulation rained down."

Stauffenberg and Haeften observed a body covered with Hitler's cloak being carried out of the briefing hut on a stretcher and assumed he had been killed. They got into a car but luckily the alarm had not yet been given when they reached Guard Post 1. The Lieutenant in charge, who had heard the blast, stopped the car and asked to see their papers. Stauffenberg who was given immediate respect with his mutilations suffered on the front-line and his aristocratic commanding exterior; said he must go to the airfield at once. After a short pause the Lieutenant let them go.

According to eyewitness testimony and a subsequent investigation by the Gestapo, Stauffenberg's briefcase containing the bomb had been moved farther under the conference table in the last seconds before the explosion in order to provide additional room for the participants around the table. Consequently, the table acted as a partial shield, protecting Hitler from the full force of the blast, sparing him from serious injury of death. The stenographer Heinz Berger, died that afternoon, and three others, General Rudolf Schmundt, General Günther Korten, and Colonel Heinz Brandt did not recover from their wounds. Hitler's right arm was badly injured but he survived.

On hearing this General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel arrested as planned 1,200 SS and Gestapo men in Paris and cut off all communication from France to Germany. (19a) The original plan was for Ludwig Beck, Erwin von Witzleben and Erich Fromm to take control of the German Army. However, General Erich Fellgiebel, sent a message to General Friedrich Olbricht to say that Hitler had survived the blast. The most calamitous flaw in Operation Valkyrie was the failure to consider the possibility that Hitler might survive the bomb attack. Olbricht told Hans Gisevius, they decided it was best to wait and to do nothing, to behave "routinely" and to follow their everyday habits. Major Albrecht Metz von Quirnheim long closely involved in the plot, had already begun the action with a cabled message to regional military commanders, beginning with the words: "The Führer, Adolf Hitler, is dead."

Stauffenberg arrived back in Berlin and went straight to see General Friedrich Fromm. Stauffenberg insisted that Hitler was dead. Fromm replied that he had just learnt from Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel that Hitler had survived the bomb attack. Stauffenberg replied, "Field Marshal Keitel is lying as usual. I myself saw Hitler being carried out dead." He then admitted that he had planted the bomb himself. Fromm became very angry and declared that all the conspirators were under arrest, whereupon Stauffenberg retorted that, on the contrary, they were in control and he was under arrest.

Shortly after the assassination attempt, Joseph Goebbels broadcast a communiqué over German radio, assuring the public that Hitler was alive and well and that he would speak to the nation later that evening. Goebbels began the broadcast with the following words: Today an attempt was made on the Führer's life with explosives... The Führer himself suffered no injuries beyond light burns and bruises. He resumed his work immediately."

Albert Speer, minister of armaments, visited Goebbels soon after the broadcast. He described the scene outside: "The office windows looked out on the street. A few minutes after my arrival I saw fully equipped soldiers, in steel helmets, hand grenades at their belts and submachine guns in their hands, moving toward the Blandenburg Gate in small, battle ready groups. They set up machine guns at the gate and stopped all traffic. Meanwhile, two heavily armed men went up to the door along the park and stood guard there." However, Goebbels was not confident that he would not be arrested and carried with him some potassium cyanide capsules.

Goebbels was safe because the July 1944 Plot had been so badly organized. No real attempt had been made to arrest the Nazi leaders or to kill them. Nor did they secure immediate control of the radio and telephone communications systems. This was surprising as weeks earlier the original plan included the seizure of the long-distance telephone office, the main telegraph office, the radio broadcasting facilities in and around Berlin, and the central post office. "Incomprehensibly, the conspirators did not carry out these actions with sufficient dispatch, and this produced utter and fatal confusion."

Later that day, Goebbels told Heinrich Himmler: "If they hadn't been so clumsy! They had an enormous chance. What dolts! What childishness? When I think how I would have handled such a thing. Why didn't they occupy the radio station and spread the wildest lies? Here they put guards in front of my door. But they let me go right ahead and telephone the Führer, mobilize everything! They didn't even silence my telephone. To hold so many trumps and botch it - what beginners!"

Sometime between 8:00 and 9:00 p.m., the cordon that the conspirators had established around the government quarter was lifted. Military units that initially had supported the conspirators were switching loyalties back to the Nazis. The main reason for this was the series of radio announcements that were broadcast throughout Germany. By 10.00 p.m., forces loyal to the government were able to seize control of central headquarters and General Friedrich Fromm was released and Claus von Stauffenberg and his followers were taken prisoner.

Those arrested included Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, Colonel-General Erich Hoepner, General Friedrich Olbricht, Colonel Albrecht Metz von Quirnheim and Lieutenant Werner von Haeften. Fromm decided that he would hold an immediate court-martial. Stauffenberg spoke out, claiming in a few clipped sentences sole responsibility for everything and stating that the others had acted purely as soldiers and his subordinates.

All the conspirators were found guilty and sentenced to death. Hoepner, an old friend, was spared to stand further trial. Beck requested the right to commit suicide. According to the testimony of Hoepner, Beck was given back his own pistol and he shot himself in the temple, but only managed to give himself a slight head wound. "In a state of extreme stress, Beck asked for another gun, and an attendant staff officer offered him a Mauser. But the second shot also failed to kill him, and a sergeant then gave Beck the coup de grâce. He was given Beck's leather overcoat as a reward."

The condemned men were taken to the courtyard. Drivers of vehicles parked in the courtyard were instructed to position them so that their headlight would illuminate the scene. General Olbricht was shot first and then it was Stauffenberg's turn. He shouted "Long live holy Germany." The salvo rang out but Haeften had thrown himself in front of Stauffenberg and was shot first. Only the next salvo killed Stauffenberg and was shot first. Only the next salvo killed Stauffenberg. Quirnheim was the last man shot. It was 12.30 a.m.

to attention next to Fromm. Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, with folder, looks on.

On this day in 1958 Margaret Haig Thomas, Lady Rhondda, died in the Westminster Hospital on 20th July 1958.

Margaret Haig Thomas was the only daughter of David Alfred Thomas and Sybil Haig, was born at Princes Square, Bayswater, on 12th June 1883. She was educated at Notting Hill High School and St Leonards School. According to her biographer, Deirdre Beddoe: "She received a sound academic education, but there really never was any serious expectation that a girl of her class would work for a living. On leaving school she took the next logical step in the career progression of an upper-class girl and came out. Chaperoned by her long-suffering mother, she endured three successive London seasons. Paralysed by shyness and incapable of small talk, she found this an agonizing experience and she took herself off to Somerville College, Oxford, primarily to escape the horrors of a fourth London season, but gave that up and returned after less than a year."

Margaret married Humphrey Mackworth in 1908. Four months later she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). She became secretary of the Newport branch and invited speakers such as Emmeline Pankhurst and Annie Kenney to Wales. During the 1910 General Election she attacked the car of Herbert Asquith. A supporter of the WSPU's arson campaign, she was sent to prison for trying to destroy a post-box with a chemical bomb. However, a hunger-strike led to her early release.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Margaret accepted the decision by the WSPU leadership to abandon its militant campaign for the vote. For the next of couple of years she worked closely with her father, who was sent by David Lloyd George to the United States to arrange the supply of munitions for the British armed forces. In May 1915, Margaret was returning from the United States on the Lusitania when it was torpedoed by a German submarine. Although over a thousand passengers died, Margaret was one of those fortunate enough to be rescued.

Awarded the title Lord Rhondda, David Alfred Thomas was appointed Minister of Food in 1917. Margaret was also given a government post as Director of of Women's Department of the Ministry of National Service. Her report on the Women's Royal Airforce in 1918 led to the dismissal of its commander, Violet Douglas-Pennant and her replacement by Helen Gwynne-Vaughan.

On the death of her father David Alfred Thomas in July 1918. As Deirdre Beddoe points out: "Margaret inherited his property, his commercial interests, and his title. The Directory of Directors for 1919 listed Viscountess Rhondda, as she now was, as the director of thirty-three companies (twenty-eight of them inherited from her father) and chairman or vice-chairman of sixteen of these. Already a famous figure whose activities were widely reported in the London press on account of her business career and of her increasingly leading role as a spokeswoman for feminism, her campaign to take her seat in the House of Lords attracted a great deal more publicity.... But although in 1922 she seemed to have won, when the committee of privileges accepted her plea for admission, the decision was reversed in May 1922."

Lady Rhondda divorced her husband and set up home with Helen Archdale. According to Archdale's biographer, David Doughan: "Helen Archdale had an intense relationship with Lady Rhondda, which seems to have begun in committee work during the First World War, though they also shared a background in suffrage militancy. By the early 1920s, she was sharing an apartment, and, together with her family, a country house (Stonepits, Kent) with Lady Rhondda."

In 1920 Lady Rhondda founded the political magazine Time and Tide. It was initially edited by her lover, Helen Archdale. In 1921 she launched the Six Point Group of Great Britain, which focused on what she regarded as the six key issues for women: The six original specific aims were: (1) Satisfactory legislation on child assault; (2) Satisfactory legislation for the widowed mother; (3) Satisfactory legislation for the unmarried mother and her child; (4) Equal rights of guardianship for married parents; (5) Equal pay for teachers; (6) Equal opportunities for men and women in the civil service.

At first Time and Tide supported left-wing causes but over the years the magazine, like its owner, moved to the right. As David Doughan points out: "However, philosophical disagreements, as well as Lady Rhondda's increasing editorial interventions, resulted in her being effectively forced out of the editorship of Time and Tide in 1926. Although she remained a director of Time and Tide Publishing Company, after her resignation specifically feminist concerns were gradually marginalized in Time and Tide."

Lady Rhondda did not allow politics to get in the way of good writing and contributors to the magazine included D. H. Lawrence, Rebecca West, Vera Brittain, Winifred Holtby, Virginia Woolf, Crystal Eastman, Charlotte Haldane, Storm Jameson, Nancy Astor, Margaret Bondfield, Margery Corbett-Ashby, Charlotte Despard, Emmeline Pankhurst, Eleanor Rathbone, Olive Schreiner, Helena Swanwick, Margaret Winteringham, Ellen Wilkinson, Ethel Smyth, Emma Goldman, George Bernard Shaw, Ernst Toller, Robert Graves and George Orwell. However, it never sold well and it is estimated that during the thirty-eight years she lost over £500,000 on the magazine.

As well as editing Time and Tide, Lady Rhondda wrote a memoir of her father and an autobiography, This Was My World (1933). After breaking up with Helen Archdale she moved in with Theodora Bosanquet, the secretary of the International Federation of University Women.

On this day in 1977 the Central Intelligence Agency releases documents about mind-control experiments. (Project MKULTRA).

In 1953 Donald Ewen Cameron developed what he called "psychic driving". Cameron developed the theory that mental patients could be cured by treatment that erased existing memories and by rebuilding the psyche completely. According to his research assistant, Dr. Peter Roper, "He (Cameron) had a technician called Leonard Rubenstein who modified cassettes so there was an endless tape, it could keep repeating itself for hours at a time. If Cameron could give a positive message, eventually a patient would respond to it." Cameron would play the tapes to his patients for up to 86 days, as they slipped in and out of insulin-induced comas.

Cameron discovered that "once a subject entered an amnesiac, somnambulistic state, they would become hypersensitive to suggestion". In other words they could be brainwashed. The CIA became aware of Cameron's research and in 1957 Cameron was recruited by Allen Dulles, Director of the CIA, to run Project MKULTRA. Documents released in 1977 show that MKULTRA was a "mind control" program. As it was illegal for the CIA to conduct operations on American soil, Cameron was forced to carry out his experiments at the Allan Memorial Institute in Canada. The CIA arranged funding via Cornell University in New York.

Cameron had to commute to Montreal every week to carry out his work. According to official documents, Cameron was paid $69,000 from 1957 to 1964 to carry out MKULTRA experiments at the Allan Memorial Institute. Documents released in 1977 revealed that thousands of unwitting subjects were tested on as part of the MKULTRA program.