On this day on 19th June

On this day in 1861 Douglas Haig, the eleventh child of John Haig, the head of the successful whisky distilling company, was born in Edinburgh. Haig was sent to Clifton College in 1875 and entered Brasenose College five years later. At Oxford University he led an active sporting and social life but left without taking a degree.

Haig went to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst in 1884. His biographer, Trevor Wilson, has argued: "There he devoted himself to his work, developed a reputation for being aloof and taciturn, passed out first in his year, and was awarded the Anson memorial sword. He also made good progress as a horseman and polo player (he had played polo at Oxford), both important attributes for a cavalry officer."

In 1885 Haig was commissioned into the 7th Queen's Hussars. His regiment was sent to India and after three years he was promoted to the rank of captain and was sent to the headquarters of the Bombay Army at Maharashtra. In 1893 he applied to enter the Camberley Staff College, but was rejected after a poor performance in the compulsory mathematics examination. Soon afterwards Haig was appointed aide-de-camp to the inspector-general of cavalry.

In 1896 he finally secured entry to the Staff College, by nomination. Other officers at the college at this time included William Robertson, Edmund Allenby, Archibald Murray and George Milne. Robertson's biographer, David R. Woodward, has argued that he came under the influence of George Henderson who had made a detailed study of Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War: "Robertson's intellectual mentor, the military theorist George F. R. Henderson, emphasized the concentration of forces in the primary theatre of the enemy in order to overwhelm his main force in a decisive battle. These principles served as a bond between Robertson and Haig when the two men dominated British military policy."

In 1897 Major General Horatio Kitchener, commander-in-chief of the British Army in Egypt, decided to attempt the reconquest of the Sudan. Kitchener applied to London for a group of special service officers to participate in his largely Egyptian force. George Henderson suggested that Haig should be sent to serve under Kitchener. In 1898 he received his first experience of warfare when he took part in the Battle of Omdurman.

Haig returned to Britain to become a brigade major at Aldershot. His commander was Major-General John French. In June 1899, French appointed Haig as his staff officer and later that year they went to South Africa to serve in the Boer War. As Trevor Wilson has pointed out: "French and Haig were then directed to Cape Town to take charge of their division, which was in the process of disembarking. They left Ladysmith amid a hail of gunfire in the last train to get away before the Boer trap closed. There followed, in December 1899, a month of disasters for nearly all British units. French's cavalry - again aided by Haig's staff work - provided an exception, holding at bay a numerically superior Boer force."

In 1900 Haig was placed in charge of a cavalry division that had to deal with the Boers who resorted to guerrilla warfare. He was also directed to capture such leading opponents such as General Jan Smuts. On his return to England he argued that cavalry would be of greater rather than less importance in coming conflicts whereas infantry and artillery would "only likely to be really effective against raw troops".

Lord Kitchener had been impressed with Haig and in 1903, when he became commander-in-chief in India, he appointed him his inspector-general of cavalry. When Haig became major-general he was the youngest officer of that rank in the British Army. Haig became responsibe for training the Indian Cavalry.

On 11th July, 1905, Haig married Dorothy Maud Vivian in the private chapel at Buckingham Palace. Vivian, the daughter of Hussey Crespigny Vivian, third Baron Vivian, and a former maid of honour to Queen Victoria and then to Queen Alexandra. Over the next few years she gave birth to three daughters and a son.

These royal connections brought him to the attention of Reginald Brett, 2nd Viscount Esher. When R. B. Haldane became Secretary of State for War in 1905, Esher persuaded him to appoint Haig as director of military training. In 1906 Halsane created the Imperial General Staff under the leadership of Haig. The following year Haldane said "the basis of our whole military fabric must be the development of the idea of a real national army, formed by the people." This became known as the Territorial Army.

According to Haldane's biographer, Colin Mathew: "Within a year there were 9,313 officers and 259,463 other ranks in the Territorial Force... His hopes that the officer training corps would act as a catalyst for a greater union between army and society were improbable, but in the officer training corps (later, in schools, the combined cadet force) he created an organization of profound significance to the ethos of British public school education for much of the twentieth century." Colonel Charles Repington, the military correspondent of The Times, and a staunch critic of the Liberal Party, described Haldane as "the best Secretary of State we have had at the War Office so far as brain and ability are concerned" and generally supported his military reforms.

Trevor Wilson argues: "Haig also aided in establishing the Imperial General Staff, under whose guidance the self-governing dominions modelled both their military establishments and their training procedures on British practices, and so readied themselves to participate alongside Britain's forces in the event of an international war."

In 1909 Haig was appointed as chief of staff in India. The following year he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-general. In 1911 R. B. Haldane arranged for Haig to take control of the 1st Army Corps of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) based in Aldershot.

On the outbreak of the First World War Haig was summoned by Herbert Henry Asquith to attend the first war council. Also present was General John French, the commander-in-chief of the BEF. At the meeting French argued that the BEF should be sent to Antwerp to help the Belgians in the defence of that city. Haig disagreed, and urged following the pre-war arrangement whereby the BEF would take its place on the left of the French Army and act in unison with it in support of Belgium.

Asquith accepted Haig's argument and Haig left for France on 15th August. Haig commanded his forces at Mons and was praised for his Ypres campaign in 1914. Later in the same year, Haig was promoted to full general and was given command of the recently enlarged BEF, under the supreme command of General John French.

The military historian, Llewellyn Woodward, has arged: "His knowledge of his profession was sound and solid; he was a man of strong nerve, resolute, patient, somewhat cold and reserved in temper, unlikely to be thrown off his balance either by calamity or success. He reached opinions slowly, and held to them. He made up his mind in 1915 that the war could be won on the Western Front, and only on the Western Front. He acted on this view, and, at the last, he was right, though it is open to argument not only that victory could have been won sooner elsewhere but that Haig's method of winning it was clumsy, tragically expensive of life, and based for too long on a misreading of the facts." Woodward has also questioned the morality of the policy of attrition. He described it as the "killing Germans until the German army was worn down and exhausted". Woodward argued that it "was not only wasteful and, intellectually, a confession of impotence; it was also extremely dangerous. The Germans might counter Haig's plan by allowing him to wear down his own army in a series of unsuccessful attacks against a skilful defence."

In December 1915, Haig was appointed commander in chief of the BEF. His close friend, John Charteris, was promoted to the rank of brigadier-general and was given the title of Chief Intelligence Officer at GHQ. This created conflict between Haig and the War Office. Christopher Andrew, the author of Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community (1985): "Haig installed his own man, Brigadier John Charteris, with Kirke as his deputy. Charteris was a determined optimist and his intelligence analyses were soon in conflict with the more realistic estimates produced by Macdonogh in the War Office. Though Kirke's sympathies were with Macdonogh, Haig sided with Charteris". Haig claimed that Macdonogh's views caused "many in authority to take a pessimistic outlook, when a contrary view, based on equally good information, would go far to help the nation onto Victory."

Major Desmond Morton served as one of Haig's adjutants. He later recalled: "He (Haig) hated being told any new information, however irrefutable, which militated against his preconceived ideas or beliefs. Hence his support for the desperate John Charteris, who was incredibly bad as head of GHQ intelligence, who always concealed bad news, or put it in an agreeable light."

General William Robertson eventually got approval for a major offensive on the Western Front in the summer of 1916. The Battle of the Somme was planned as a joint French and British operation. The idea originally came from the French Commander-in-Chief, Joseph Joffre and was accepted by General Haig, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) commander, despite his preference for a large attack in Flanders. Although Joffre was concerned with territorial gain, it was also an attempt to destroy German manpower.

At first Joffre intended for to use mainly French soldiers but the German attack on Verdun in February 1916 turned the Somme offensive into a large-scale British diversionary attack. General Haig now took over responsibility for the operation and with the help of General Henry Rawlinson, came up with his own plan of attack. Haig's strategy was for a eight-day preliminary bombardment that he believed would completely destroy the German forward defences.

Douglas Haig later pointed out in his book, Dispatches (1919): "The enemy's position to be attacked was of a very formidable character, situated on a high, undulating tract of ground. The first and second systems each consisted of several lines of deep trenches, well provided with bomb-proof shelters and with numerous communication trenches connecting them. The front of the trenches in each system was protected by wire entanglements, many of them in two belts forty yards broad, built of iron stakes, interlaced with barbed-wire, often almost as thick as a man's finger. Defences of this nature could only be attacked with the prospect of success after careful artillery preparation."

General Rawlinson was was in charge of the main attack and his Fourth Army were expected to advance towards Bapaume. To the north of Rawlinson, General Edmund Allenby and the British Third Army were ordered to make a breakthrough with cavalry standing by to exploit the gap that was expected to appear in the German front-line. Further south, General Fayolle was to advance with the French Sixth Army towards Combles.

General Haig used 750,000 men (27 divisions) against the German front-line (16 divisions). However, the bombardment failed to destroy either the barbed-wire or the concrete bunkers protecting the German soldiers. This meant that the Germans were able to exploit their good defensive positions on higher ground when the British and French troops attacked at 7.30 on the morning of the 1st July. The BEF suffered 58,000 casualties (a third of them killed), therefore making it the worse day in the history of the British Army.

Haig was not disheartened by these heavy losses on the first day and ordered General Henry Rawlinson to continue making attacks on the German front-line. A night attack on 13th July did achieve a temporary breakthrough but German reinforcements arrived in time to close the gap. Haig believed that the Germans were close to the point of exhaustion and continued to order further attacks expected each one to achieve the necessary breakthrough. Although small victories were achieved, for example, the capture of Pozieres on 23rd July, these gains could not be successfully followed up.

Colonel Charles Repington, the military correspondent of The Times, had a meeting with Haig during the offensive at the Somme: "He explained things on the map. It is staff work rather than generalship which is necessary for this kind of fighting. He laid great stress on his raids, and he showed me on a map where these had taken place. He said that he welcomed criticisms, but when I mentioned the criticisms which I had heard of his misuse of artillery on July 1, he did not appear to relish it, and denied its truth. As he was not prepared to talk of things of real interest, I said very little, and left him to do the talking. I also had a strong feeling that the tactics of July 1 had been bad. I don't know which of us was the most glad to be rid of the other."

Christopher Andrew, the author of Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community (1985), has argued that Brigadier-General John Charteris, the Chief Intelligence Officer at GHQ. was partly responsible for this disaster: "Charteris's intelligence reports throughout the five-month battle were designed to maintain Haig's morale. Though one of the intelligence officer's duties may be to help maintain his commander's morale, Charteris crossed the frontier between optimism and delusion." As late as September 1916, Charteris was telling Haig: "It is possible that the Germans may collapse before the end of the year."

On 15th September General Alfred Micheler and the Tenth Army joined the battle in the south at Flers-Courcelette. Despite using tanks for the first time, Micheler's 12 divisions gained only a few kilometres. Whenever the weather was appropriate, General Haig ordered further attacks on German positions at the Somme and on the 13th November the BEF captured the fortress at Beaumont Hamel. However, heavy snow forced Haig to abandon his gains.

Robertson's biographer, David R. Woodward, has pointed out: "British losses on the first day of the Somme offensive - almost 60,000 casualties - shocked Robertson. Haig's one-step breakthrough attempt was the antithesis of Robertson's cautious approach of exhausting the enemy with artillery and limited advances. Although he secretly discussed more prudent tactics with Haig's subordinates he defended the BEF's operations in London. The British offensive, despite its limited results, was having a positive effect in conjunction with the other allied attacks under way against the central powers. The continuation of Haig's offensive into the autumn, however, was not so easy to justify."

Captain Charles Hudson was one of those officers who took part in the battle. He later wrote: "It is difficult to see how Haig, as Commander-in-Chief living in the atmosphere he did, so divorced from the fighting troops, could fulfil the tremendous task that was laid upon him effectively. I did not believe then, and I do not believe now that the enormous casualties were justified. Throughout the war huge bombardments failed again and again yet we persisted in employing the same hopeless method of attack. Many other methods were possible, some were in fact used but only half-heartedly."

Private James Lovegrove was also highly critical of Haig's tactics: "The military commanders had no respect for human life. General Douglas Haig... cared nothing about casualties. Of course, he was carrying out government policy, because after the war he was knighted and given a lump sum and a massive life-pension. I blame the public schools who bred these ego maniacs. They should never have been in charge of men. Never."

With the winter weather deteriorating General Haig now brought an end to the Somme Offensive. Since the 1st July, the British has suffered 420,000 casualties. The French lost nearly 200,000 and it is estimated that German casualties were in the region of 500,000. Allied forces gained some land but it reached only 12km at its deepest points. Haig wrote at the time: "The results of the Somme fully justify confidence in our ability to master the enemy's power of resistance."

Encouraged by the gains made at the offensive at Messines in June 1917, Haig became convinced that the German Army was now close to collapse and once again made plans for a major offensive to obtain the necessary breakthrough. The opening attack at Passchendaele was carried out by General Hubert Gough and the British Fifth Army with General Herbert Plumer and the Second Army joining in on the right and General Francois Anthoine and the French First Army on the left. After a 10 day preliminary bombardment, with 3,000 guns firing 4.25 million shells, the British offensive started at Ypres a 3.50 am on 31st July.

Allied attacks on the German front-line continued despite very heavy rain that turned the Ypres lowlands into a swamp. The situation was made worse by the fact that the British heavy bombardment had destroyed the drainage system in the area. This heavy mud created terrible problems for the infantry and the use of tanks became impossible.

As William Beach Thomas, a journalist working for The Daily Mail, pointed out: "Floods of rain and a blanket of mist have doused and cloaked the whole of the Flanders plain. The newest shell-holes, already half-filled with soakage, are now flooded to the brim. The rain has so fouled this low, stoneless ground, spoiled of all natural drainage by shell-fire, that we experienced the double value of the early work, for today moving heavy material was extremely difficult and the men could scarcely walk in full equipment, much less dig. Every man was soaked through and was standing or sleeping in a marsh. It was a work of energy to keep a rifle in a state fit to use."

Lieutenant Robert Sherriff was a junior officer at Passchendaele: "The living conditions in our camp were sordid beyond belief. The cookhouse was flooded, and most of the food was uneatable. There was nothing but sodden biscuits and cold stew. The cooks tried to supply bacon for breakfast, but the men complained that it smelled like dead men."

The German Fourth Army held off the main British advance and restricted the British to small gains on the left of the line. Haig now called off the attacks and did not resume the offensive until the 26th September. An attack on 4th October enabled the British forces to take possession of the ridge east of Ypres. Despite the return of heavy rain, Haig ordered further attacks towards the Passchendaele Ridge. Attacks on the 9th and 12th October were unsuccessful. As well as the heavy mud, the advancing British soldiers had to endure mustard gas attacks.

Three more attacks took place in October and on the 6th November the village of Passchendaele was finally taken by British and Canadian infantry. The offensive cost the British Army about 310,000 casualties and Haig was severely criticised for continuing with the attacks long after the operation had lost any real strategic value.

Lieutenant Bernard Montgomery was also highly critical of his senior officers on the Western Front during the First World War. "The higher staffs were out of touch with the regimental officers and with the troops. The former lived in comfort, which became greater as the distance of their headquarters behind the lines increased. There was no harm in this provided there was touch and sympathy between the staff and the troops. This was often lacking. The frightful casualties appalled me. There is a story of Sir Douglas Haig's Chief of Staff who was to return to England after the heavy fighting during the winter of 1917-18 on the Passchendaele front. Before leaving he said he would like to visit the Passchendaele Ridge and see the country. When he saw the mud and the ghastly conditions under which the soldiers had fought and died." Apparently he was upset by what he saw and said: "Do you mean to tell me that the soldiers had to fight under such conditions? Why was I never told about this before?"

Haig's biographer, Trevor Wilson, has defended his tactics during the First World War: "Haig's critics have rarely acknowledged the formidable problems which confronted him. He was required - by his political masters, by a vociferous media, and by the determination of the British public - not just to hold the line but to get on and win the war: that is, to carry the struggle to the enemy and drive the invader from the soil of France and Belgium. Yet consequent upon the relative equality of manpower and industrial resources between the two sides, and upon the clear advantages which developments in weaponry had bestowed upon the defender, there was no sure path to victory on offer, and any offensive operation was bound to bring heavy loss of life upon the attacking forces. Nor do Haig's critics usually notice the respects in which he responded positively to the changing face of warfare. For example, he embraced with enthusiasm both new devices of battle, such as tanks and aircraft, and new methods of employing established weaponry, such as striking innovations for increasing the effectiveness of artillery: aerial photography, sound-ranging, and flash-spotting."

After the failure of British tanks in the thick mud at Passchendaele, Colonel John Fuller, chief of staff to the Tank Corps, suggested a massed raid on dry ground between the Canal du Nord and the St Quentin Canal. General Julian Byng, commander of the Third Army, accepted Fuller's plan, although it was originally vetoed by Haig. However, he changed his mind and decided to launch the Cambrai Offensive.

In September 1917 a munity took place at Etaples. Private William Brooks was one of those who was present at these disturbances: "There was a big riot by the Australians at a place called Etaples. They called it collective indiscipline, what it was was mutiny. It went on for days. I think a couple of military police got killed. Field Marshall Haig would have shot the leaders but dared not of course because they were Aussies. Haig's nickname was the butcher. He'd think nothing of sending thousands of men to certain death. The utter waste and disregard for human life and human suffering by the so-called educated classes who ran the country. What a wicked waste of life. I'd hate to be in their shoes when they face their Maker."

Brigadier-General John Charteris, the Chief Intelligence Officer at GHQ was involved in the planning of the offensive at Cambrai in November 1917. Lieutenant James Marshall-Cornwall discovered captured documents that three German divisions from the Russian front had arrived to strengthen the Cambrai sector. Charteris told Marshall-Cornwall: "This is a bluff put up by the Germans to deceive us. I am sure the units are still on the Russian front... If the commander in chief were to think that the Germans had reinforced this sector, it might shake his confidence in our success."

Douglas Haig, who was not given this information, ordered a massed tank attack at Artois. Launched at dawn on 20th November, without preliminary bombardment, the attack completely surprised the German Army defending that part of the Western Front. Employing 476 tanks, six infantry and two cavalry divisions, the British Third Army gained over 6km in the first day. Progress towards Cambrai continued over the next few days but on the 30th November, 29 German divisions launched a counter-offensive.

By the time that fighting came to an end on 7th December, 1917, German forces had regained almost all the ground it lost at the start of the Cambrai Offensive. During the two weeks of fighting, the British suffered 45,000 casualties. Although it is estimated that the Germans lost 50,000 men, Haig considered the offensive as a failure and reinforced his doubts about the ability of tanks to win the war.

An official inquiry carried out after the military defeat at Cambrai blamed Brigadier-General John Charteris for "intelligence failures". The Secretary of State for War, the Earl of Derby, insisted that Haig sacked Charteris and in January 1918, he was appointed as deputy director of transportation in France. Haig wrote at the time: "He (Charteris) seems almost a sort of Dreyfus in the eyes of our War Office authorities."

The journalist, Henry Hamilton Fyfe, met Haig several times during the war: "Haig was, in truth, at close quarters very disappointing. He looked the part. His face on a postcard was not less impressive than Kitchener's. But - his face was his fortune. He had little general intelligence, no imagination.... Haig was as shy as a schoolgirl. He was afraid of newspaper men - afraid of any men but those he gathered round him, and they were mostly like himself. If ever the history of the war is written as frankly as that of Napoleon's campaign has been, Haig will be held accountable for the appalling slaughter in the Somme battles and in Flanders, caused by his flinging masses of men against positions far too strong to be carried by assault."

In 1918 Haig took charge of the successful British advances on the Western Front which led to an Allied victory later that year. John Buchan wrote: "When the last great enemy attack came he (Haig) took the main shock with a quiet resolution; when the moment arrived for the advance he never fumbled. He broke through the Hindenburg line in spite of the doubts of the British Cabinet, because he believed that only thus could the War be ended in time to save civilisation. He made the decision alone - one of the finest proofs of moral courage in the history of war. Haig cannot enter the small circle of the greater captains, but it may be argued that in the special circumstances of the campaign his special qualities were the ones most needed - patience, sobriety, balance of temper, unshakable fortitude."

After the war Haig was posted as commander in chief of home forces until his retirement in 1921. Haig was granted £100,000 by the British government. This did not go down well with those soldiers who were finding it difficult to find work during this period. George Coppard wrote: "During this time the government, in the flush of victory, were busily engaged in fixing the enormous sums to be voted as gratuities to the high-ranking officers who had won the war for them. Heading the formidable list were Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig and Admiral Sir David Beatty. For doing the jobs for which they were paid, each received a tax-free golden handshake of £100,000 (a colossal sum then), an earldom and, I believe, an estate to go with it."

Haig devoted the rest of his life to the welfare of ex-servicemen via the Royal British Legion. He was made Earl Haig in 1919 and then Baron Haig of Bemersyde in 1921. Trevor Wilson has pointed out: "These united existing associations of former servicemen in a single body for each country, and Haig became president of both organizations. And he accepted chairmanship of the United Services Fund, formed to administer for the benefit of former soldiers and their families the large profits made during the war by army canteens. At the time these bodies constituted between them the largest benevolent organization ever formed in Britain."

In the 1920s Haig was severely criticised for the tactics used at offensives such as the one at the Somme. This included the prime minister of the time, David Lloyd George: "It is not too much to say that when the Great War broke out our Generals had the most important lessons of their art to learn. Before they began they had much to unlearn. Their brains were cluttered with useless lumber, packed in every niche and corner. Some of it was never cleared out to the end of the War. They knew nothing except by hearsay about the actual fighting of a battle under modern conditions. Haig ordered many bloody battles in this War. He only took part in two. He never even saw the ground on which his greatest battles were fought, either before or during the fight. The tale of these battles constitutes a trilogy, illustrating the unquestionable heroism that will never accept defeat and the inexhaustible vanity that will never admit a mistake."

Duff Cooper, who was commissioned by the Haig family to write his official biography, argued: "There are still those who argue that the Battle of the Somme should never have been fought and that the gains were not commensurate with the sacrifice. There exists no yardstick for the measurement of such events, there are no returns to prove whether life has been sold at its market value. There are some who from their manner of reasoning would appear to believe that no battle is worth fighting unless it produces an immediately decisive result which is as foolish as it would be to argue that in a prize fight no blow is worth delivering save the one that knocks the opponent out. As to whether it were wise or foolish to give battle on the Somme on the first of July, 1916, there can surely be only one opinion. To have refused to fight then and there would have meant the abandonment of Verdun to its fate and the breakdown of the co-operation with the French."

It seemed that Haig had not learnt the lessons of the First World War. In 1926 he wrote: "I believe that the value of the horse and the opportunity for the horse in the future are likely to be as great as ever. Aeroplanes and tanks are only accessories to the men and the horse, and I feel sure that as time goes on you will find just as much use for the horse - the well-bred horse - as you have ever done in the past."

Douglas Haig died suddenly of heart failure, at 21 Prince's Gate, London, on 29th January 1928. He was accorded a state funeral in Westminster Abbey. He was buried at Dryburgh Abbey, near Bemersyde, in the Scottish Borders.

On this day in 1885 Adela Pankhurst, the youngest daughter of Dr. Richard Pankhurst and Emmeline Pankhurst, was born in Manchester. She had two older sisters, Christabel Pankhurst and Sylvia Pankhurst. According to Fran Abrams: "There was no great novelty to the addition of a third girl to the existing brood, and in any case this child was a sickly creature. She had weak legs and bad lungs, and for a time was not expected to live." Adela was forced to wear splints on her legs and did not learn to walk until she was three.

Adela later recalled how her father played an important role in her education: "I think I was only about six when my father - a most revered person in my existence - assured me there was no God." She was happy at her first school in Southport but did not like her experience at Manchester Girls' High School. On one occasion she tried to run away from school and home.

Richard Pankhurst, a radical lawyer, was one of the Independent Labour Party candidates in Manchester, who had been defeated in the 1895 General Election. Christabel's father died of a perforated ulcer in 1898 but his wife and her two older daughters remained active in politics.

Adela was a bright student and her teachers suggested that she should apply for an Oxford University scholarship. Emmeline Pankhurst was against the idea but the plan was only abandoned after she caught scarlet fever in 1901. Her mother sent her to Switzerland and when Adela returned to Manchester she was determined to become a teacher. Although her mother objected as she saw it as a "working-class occupation" by 1903 was working as a pupil-teacher at an elementary school in Urmston.

Emmeline Pankhurst was a member of the Manchester branch of the NUWSS. By 1903 Pankhurst had become frustrated at the NUWSS lack of success. With the help of her three daughters, Adela, Christabel Pankhurst and Sylvia Pankhurst, she formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). At first the main aim of the organisation was to recruit more working class women into the struggle for the vote.

By 1905 the media had lost interest in the struggle for women's rights. Newspapers rarely reported meetings and usually refused to publish articles and letters written by supporters of women's suffrage. In 1905 the WSPU decided to use different methods to obtain the publicity they thought would be needed in order to obtain the vote.

On 13th October 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were arrested and charged with assault.

Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney were found guilty of assault and fined five shillings each. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison. The case shocked the nation. For the first time in Britain women had used violence in an attempt to win the vote. Members of the WSPU now became known as suffragettes.

Adela Pankhurst was given the task of disturbing meetings held by Winston Churchill. Another member of the WSPU, Hannah Mitchell, was with her when she was arrested while disrupting one of Churchill's political meeting: "I followed Adela who was in the grip of a big burly officer who kept telling her she ought to be smacked and set to work at the wash tubs. She grew so angry that she slapped his hand, which was as big as a ham." Adela was found guilty of assaulting a policeman. She refused to pay and was sent to Strangeways prison for seven days.

On her release Adela wrote an account of her experiences in The Labour Record: "As a teacher I had been trying for years in the case of the children with whom I had to deal to stave off the inevitable answer... I had felt the hopeless futility of my work. Now, in prison... it seemed to me that for the first time in my life I was doing something which would help."

In early 1907 she and Helen Fraser organized the WSPU campaign at the Aberdeen South by-election. Fraser later recalled: "It was winter and very cold. I met her at the station and was horrified at her breathing. I took her to lodgings and sent for the doctor, who, like me, was very critical of her being allowed to travel. She had pneumonia." The campaign was a success and the Liberal Party majority of George Birnie Esslemont was reduced from 4,000 to under 400.

Adela continued her campaign against Winston Churchill and in October 1909, she was assaulted by Liberal Party stewards in Abernethy. A few days later she arrested for throwing stones at a hall where Churchill was about to speak. While in prison she went on hunger strike. The doctor who treated Adela described her as "a slender under-sized girl five feet in height and seven stones in weight." He added that she was of a "degenerate type". She was deemed unfit for force feeding and was released from prison.

Sylvia Pankhurst argued in The Suffrage Movement that Adela did not get the credit she deserved for the role she played in the campaign: "The desire was a reaction from the knowledge that though a brilliant speaker and one of the hardest workers in the movement, she was often regarded with more disapproval than approbation by Mrs Pankhurst and Christabel, and was the subject of a sharper criticism than the other organisers had to face."

Adela Pankhurst became concerned about the increase in the violence used by the Women's Social and Political Union. She later told fellow member, Helen Fraser: "I knew all too well that after 1910 we were rapidly losing ground. I even tried to tell Christabel this was the case, but unfortunately she took it amiss." After arguing with Emmeline Pankhurst about this issue she left the WSPU in October 1911. Sylvia Pankhurst was also critical of this new militancy. Christabel Pankhurst replied that "I would not care if you were multiplied by a hundred, but one of Adela is too many."

In 1912 Adela embarked on a diploma course at Studley Horticultural College in Worcestershire. The following year she found employment as head gardener with a family in Bath. Adela, whose health was not very good, struggled with this work and in 1914, Emmeline Pankhurst, who was worried that her daughter would criticise the WSPU in public, agreed to pay for a one-way ticket to Australia.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men.

Adela, like her sister Sylvia Pankhurst, completely rejected this strategy and in Australia she joined with Vida Goldstein in the campaign against the First World War. Adela believed that her actions were true to her father's belief in international socialism. Adela and Goldstein established the Australian Women's Peace Army. She wrote to Sylvia that like her she was "carrying out her father's work". Emmeline Pankhurst completely rejected this approach and told Sylvia that she was "ashamed to know where you and Adela stand." Edgar Ross, a fellow campaigner against the war in Melbourne later recalled: "What I remember most about her was her courage. She would stand, unfearing, in front of jingo-mad soldiers heckling her when speaking on the platform."

On 30th September 1917, Adela married Tom Walsh, a widower with three children. He was also an organiser for the Seamen's Union of Australia. Six days later she was sentenced to four months' imprisonment for a series of public order offences carried out during demonstrations against conscription. Adela was released in January 1918.

In 1921 Adela and Tom became members of the executive committee of the Australian Communist Party. However, they did not remain party members for long and they began to drift to the right. In 1928 she founded the Australian Women's Guild of Empire. It was based on the Women's Guild of Empire, an organisation formed by Flora Drummond in London. The Women's Guild initially raised money for working class women and children hit by the Great Depression. It advocated the need for industrial cooperation and criticised trade union activity. It was also a patriotic organisation which developed strong anti-communist views.

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003): "She (Adela Pankhurst) saw herself as a champion of the poor, even though her new organisation condemned working mothers, abortion, contraception, communism and trade unions. When she made a tour of the Australian coalfields to attack the unions during a lock-out, she talked mostly about how the children of the miners were suffering. She used her guild to start a welfare agency for families struggling in industrial areas."

In addition to her three step-daughters, Adela had five children of her own - Richard named after her father, Sylvia after her sister, Christian, Ursula and Faith, who died soon after she was born. Ursula later recalled: "We children never felt neglected and felt nothing for her but love, respect and a strange desire to protect her." Emmeline Pankhurst never saw any of Adela's children. However, she also moved sharply to the right in the 1920s and a few weeks before her death in 1928, she wrote to Adela expressing regret for the long rift between them.

Adela Pankhurst continued to drift to the right and showed some sympathy for what Adolf Hitler was doing in Nazi Germany. On the outbreak of the Second World War she was asked to resign from the Australian Women's Guild of Empire. The following month she caused a stir when she and Tom Walsh, went on a goodwill mission to Japan. In March 1942 she was interned for her pro-Japanese views. She was released after more than a year in custody, just before her husband's death in April 1943.

After the war Adela did not play an active role in politics. In 1949 she told her friend Helen Fraser that she had been persecuted because of her hostility to communism: "So long did I warn my supporters that co-operation with Russia and all those who supported the Bolsheviks was the way to disaster and I was ruined and interned for my pains... Communism has not brought home the bacon... Taken on achievement, Fascism did very much better while it lasted. Officially we don't admit this but actually I believe most people who are interested know it perfectly well"

Adela Pankhurst died in Australia on 23rd May, 1961.

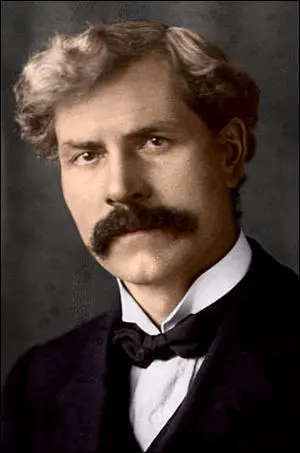

On this day in 1891 Helmut Herzfeld was born in Berlin, Germany. His father, Franz Held, was a socialist writer and his mother, Alice Stolzenberg, was a textile worker and a trade union activist. As a result of their politics the family was forced to flee to Switzerland in 1896.

After leaving school at fourteen Herzfeld worked for a bookseller, Heinrich Heuss, in Wiesbaden. In 1907 he became an assistant to the painter, Hermann Bouffier, and two years later became a student at the School of Applied Arts in Munich. In 1912 Herzfeld started work as a designer in Mannheim for a year before moving to Berlin to study under Ernst Neumann at the Arts and Crafts School.

Helmut Herzfeld was drafted into the German Army in 1915 but succeeds in evading military service. Karl Liebknecht, the leader of the Spartacus League, a secret organization, published a pamphlet, The Main Enemy Is At Home! He argued: "The main enemy of the German people is in Germany: German imperialism, the German war party, German secret diplomacy. This enemy at home must be fought by the German people in a political struggle, cooperating with the proletariat of other countries whose struggle is against their own imperialists. We think as one with the German people – we have nothing in common with the German Tirpitzes and Falkenhayns, with the German government of political oppression and social enslavement. Nothing for them, everything for the German people. Everything for the international proletariat, for the sake of the German proletariat and downtrodden humanity."

On 1st May, 1916, the Spartacus League decided to come out into the open and organized a demonstration against the First World War in Berlin. Helmut Herzfeld was in the crowd that day and heard Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg call for everyone to resist Germany's involvement in the war. Several of its leaders, including Liebknecht and Luxemburg were arrested and imprisoned. Wieland Herzfelde, said that the speeches at the rally had a great influence on his brother. It was at this point he decided to dedicate his art to politics. Wieland later wrote: "We are the soldiers of peace. No nation and no race is our enemy." A pacifist and Marxist, Herzfeld, changed his name to John Heartfield in 1916 in "protest against German nationalistic fervour".

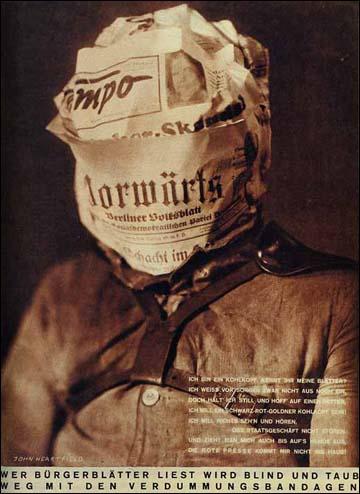

Heartfield began contributing work to Die Neue Jugend, an arts journal published by his brother. His friend, George Grosz, who worked with him at the journal, later recalled how John Heartfield "developed a new very amusing style of using collage and bold typography". Grosz helped him develop what became known as photomontage (the production of pictures by rearranging selected details of photographs to form a new and convincing unity). We... invented photomontage in my South End studio at five o'clock on a May morning in 1916, neither of us had any inkling of its great possibilities, nor of the thorny yet successful road it was to take. As so often happens in life, we had stumbled across a vein of gold without knowing it."

In 1918 Heartfield, Grosz and Erwin Piscator joined the newly formed German Communist Party (KPD) and over the next fifteen years produced designs and posters for the organization. He participated in the First International Dada Fair of 1920. It is claimed that Heartfield had a major influence on the German Dada group that included Otto Dix, Max Ernst, Raoul Hausmann and Kurt Schwitters.

Sergei Tretyakov was another artist linked to the Dada group. "Heartfield's first Dadaist photomontages are still marked by their abstract nature. Scraps of photograph and printed text are arranged not so much according to meaning but according to the aesthetic mood of the artist. The Dadaist period in Heartfield's work did not continue for long. He soon ceased to waste his artistic talents in abstract fireworks. His works became aimed shots... Soon no line could be drawn between his montages and his party work."

Over the next few years John Heartfield produced posters for the KPD. However, to earn a living he worked briefly as a set designer for Max Reinhardt and more consistently for the revolutionary theatre of Erwin Piscator. He also designed book jackets for the left-wing publishers, Malik Verlag. In 1923 Heartfield became editor of the satirical magazine, Der Knöppel.

Bertolt Brecht first met Heartfield in 1924. He pointed out that he soon became one of the most important European artists. "He works in a field that he created himself, the field of photomontage. Through this new form of art he exercises social criticism. Steadfastly on the side of the working class, he unmasked the forces of the Weimar Republic driving toward war." Heartfield wrote: "Art and agitation are mutually exclusive".

Wieland Herzfelde argued "he consciously placed photography in the service of political agitation". In 1928 he created The Face of Fascism, a montage that dealt with the rule of Benito Mussolini which spread all over Europe with tremendous force. "A skull-like face of Mussolini is eloquently surrounded by his corrupt backers and his dead victims".

Heiri Strub has pointed out that Heartfield made the decision to use his art for political causes. "Heartfield always considered his photomontages as artistic achievements. He took in stride the fact that he was not recognized by contemporary art critics. The works he created for dissemination in huge editions had no value in the art market. Directing his political charges at the masses, he could scarcely count on a sympathetic reaction from bourgeois art collectors. The worker, however, for whom he intended his photomontages, understood their revolutionary content, but assigned no artistic value judgment to them."

Heartfield began working for the socialist magazine, Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (AIG) in 1929. During this period it became the most widely socialist pictorial newspaper in Germany. Circulation reached 350,000 in 1930. Zbyněk Zeman has pointed out that at this stage Heartfield concentrated his attack on "Prussian militarism and the large-scale industries and industrialists who supplied it with arms".

The German novelist, Heinrich Mann, was one of those who saw the significance of the magazine: "The Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung is one of the best of current picture newspapers. It is full in its coverage, technically good, and, above all, unusual and new... Aspects of daily life are seen here through the eyes of the worker, and it is time that this happened. The pictures express complaints and threats reflecting the attitude of the proletariat - but at the same time this proves their self-confidence and their energetic activity to help themselves. The self-confidence of the proletariat in this weary part of the world is most heartening."

Heiri Strub worked with Heartfield at the magazine. "Heartfield's high demands of quality made collaboration with him difficult. His long-time colleague, the photographer Janos Reismann, related how Heartfield constantly demanded new pictures until he saw his idea realized... With photographic tricks and painting Heartfield arranged the parts of the photo to fit together seamlessly. With extraordinary care he devised his adhesive picture, so that after final retouching it went straight to the printer. Since the AIZ was produced using the highly sensitive copperplate photogravure method, errors were as evident as the artist's real intention. Heartfield's respect for the skills of others was so great that he himself did not do the photography, and he left the retouching to others, but always under his stringent supervision."

Louis Aragon has argued: "John Heartfield is one of those who expressed the strongest doubts about painting, especially its technical aspects... As we know, Cubism was a reaction of painters to the invention of photography. The photograph and the cinema made it seem childish to them to strive for verisimilitude. By means of these new technical accomplishments they created a conception of art which led some to attack naturalism and others to a new definition of reality. With Leger it led to decorative art, with Mondrian to abstraction, with Picabia to the organization of mundane evening entertainment. But toward the end of the war, several men in Germany (Grosz, Heartfield, Ernst) were led through the critique of painting to a spirit which was quite different from the Cubists, who pasted a piece of newspaper on a matchbox in the middle of the picture to give them a foothold in reality. For them the photograph stood as a challenge to painting and was released from its imitative function and used for their own poetic purpose."

John Heartfield's main target in the early 1930s was Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party. His work often appeared on the front cover of AIG. In 1930 the magazine published twelve of his photomontages. This included one that showed Fritz Thyssen, the owner of United Steelworks, a company that controlled more that 75 per cent of Germany's ore reserves and employed 200,000 people. In the photomontage, Thyssen is shown working Hitler as a puppet.

In 1932 Heartfield produced 18 photomontages for AIG. The most famous of these appeared just before the November 1932 General Election. Hitler is showed standing in front of a large man who represents big business. The man is handing over money to Hitler. Printed underneath are the words: "Motto: Millions stand behind me! A little man asks for gifts". Heartfield's friend, Oskar Maria Graf, commented, that all his work was now politically motivated, "the intolerable aspect of events is the motor of his art".

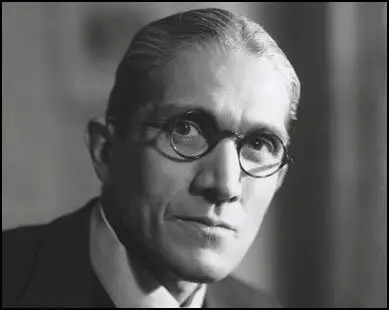

Richard Carline was an English artist who met him during this period: "Slight and little more than five feet tall, Heartfield displayed the unmistakable traits of genius - single-minded and purposeful. With his intense, unpretentious, and uninhibited personality, he warmed toward everyone he met without regard for class or background. He would talk to animals as if they were humans."

In the election in November 1932 the Nazi Party won 230 seats, making it the largest party in the Reichstag. The German National Party, won nearly a million additional votes. However the German Social Democrat Party (133) and the German Communist Party (89) still had the support of the urban working class and Hitler was deprived of an overall majority in parliament. In numerical terms, the socialist parties obtained 13,228,000 votes compared to the 14,696,000 votes recorded for the Nazis and the German Nationalists.

Soon after Hitler became chancellor in January 1933 he announced new elections. Hermann Goering called a meeting of important industrialists where he told them that the election would be the last in Germany for a very long time. He explained that Hitler "disapproved of trade unions and workers' interference in the freedom of owners and managers to run their concerns." Goering added that the NSDAP would need a considerable amount of of money to ensure victory. Those present responded by donating 3 million Reichmarks. As Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary after the meeting: "Radio and press are at our disposal. Even money is not lacking this time."

On 27th February, 1933, the Reichstag caught fire. When they police arrived they found Marinus van der Lubbe on the premises. After being tortured by the Gestapo he confessed to starting the Reichstag Fire. However he denied that he was part of a Communist conspiracy. Hermann Goering refused to believe him and he ordered the arrest of several leaders of the German Communist Party (KPD).

When Hitler heard the news about the fire he gave orders that all leaders of the German Communist Party should "be hanged that very night." Paul von Hindenburg vetoed this decision but did agree that Hitler should take "dictatorial powers". KPD candidates in the election were arrested and Hermann Goering announced that the Nazi Party planned "to exterminate" German communists. John Heartfield responded to these events by producing Goering the Executioner of the Third Reich. It shows the "human bloodhound with his axe standing in front of the burning parliament."

Behind the scenes Goering, who was minister of the interior in Hitler's government, was busily sacking senior police officers and replacing them with Nazi supporters. These men were later to become known as the Gestapo. Goering also recruited 50,000 members of the Sturm Abteilung (SA) to work as police auxiliaries. Goering then raided the headquarters of the German Communist Party (KPD) in Berlin and claimed that he had uncovered a plot to overthrow the government. Leaders of the KPD were arrested but no evidence was ever produced to support Goering's accusations. He also announced he had discovered a communist plot to poison German milk supplies.

Thousands of members of the Social Democrat Party and trade union activists were arrested and sent to recently opened concentration camps. Left-wing election meetings were broken up by the Sturm Abteilung (SA) and several candidates were murdered. Newspapers that supported these political parties were closed down during the election. Although it was extremely difficult for the opposition parties to campaign properly, Hitler and the Nazi party still failed to win an overall victory in the election on 5th March, 1933. The Nazi Party received 43.9% of the vote and only 288 seats out of the available 647. The increase in the Nazi vote had mainly come from the Catholic rural areas who feared the possibility of an atheistic Communist government.

Adolf Hitler ordered the arrests of all those artists that had criticized him during his rise to power. (30) On 16th April, 1933, members of the Sturmabteilung (SA) arrived at Heartfield's apartment. Heartfield had been warned about what was going to happen and he managed to flee to Prague. This now became the place where AIG was published. That year Heartfield produced 35 front-covers. However, it was very difficult to smuggle the magazine back to Germany and circulation dropped dramatically from the 500,000 copies that were being sold before Hitler took power.

All forms of mass communication were now controlled in Nazi Germany. The man in overall charge was Dr. Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda. Lists were drawn up of books the Nazis believed contained "un-German" ideas and then all available copies were publically destroyed. The Nazis were especially hostile to works produced by left-wing writers like Bertolt Brecht and Ernst Toller.

John Heartfield was especially upset by the passing of the Enabling Bill. This banned the German Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party from taking part in future election campaigns. This was followed by Nazi officials being put in charge of all local government in the provinces (7th April), trades unions being abolished, their funds taken and their leaders put in prison (2nd May), and a law passed making the Nazi Party the only legal political party in Germany (14th July). This situation motivated Heartfield to produce the Executioner and Justice on 30th November 1933.

Adolf Hitler became increasingly annoyed with John Heartfield's photomontages published in Prague (35 in 1933) and he told the government in Czechoslovakia to ban his work. In May 1934 the authorities agreed to Hitler's demands. This created a great deal of controversy and the French artist, Paul Signac, urged international action. He wrote a letter to Heartfield's supporters in Prague: "My whole life long I have been fighting for the freedom of art... I am prepared to contribute my share in organizing a French exhibition of our friend's works... The club is poised for battle against the freedom of the spirit. Let us unite to defend ourselves."

The French poet, Louis Aragon, argued in Commune Magazine: "John Heartfield today knows how to salute beauty. He knows how to create those images which are the beauty of our rage since they represent the cry of the people - the representation of the people's struggle against the brown hangman with his craw crammed with gold pieces. He knows how to create these realistic images of our life and struggle arresting and gripping for millions of people who themselves are a part of that life and struggle. His art is art in Lenin's sense for it is a weapon in the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat."

Heartfield's friends in Europe helped to get his work published. Several photomontages on the Spanish Civil War were published. This included Madrid 1936, a work of art that dealt with the Siege of Madrid. Another poster, The Mothers to their Sons in Franco's Service, was published in December 1936. On the poster it said: "For what you were hired. Whom you are hounding. So permit us mothers to tell you: We grieve for you, young ones. No, we did not raise you to murder. You are allowing yourselves to be abused. You have been betrayed!"

In October 1937 John Heartfield published Warning. In the photomontage an audience looks at a scene of horror caused by Japanese air raids in Manchuria. "Heartfield's pastiche layers in several rows of faceless male heads, backs towards us, beneath the frontal stare of an on-screen victim in the violent newsreel footage at which they are staring: a Chinese mother holding a bloodied child in outsized close-up." It had the caption: "Today you see a film of war in other countries. But remember, if you don't unite to resist it now, tomorrow it will kill you, too!" It was a prediction that was to come true within two years.

When Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of Czechoslovakia after the Munich Agreement of 1938 John Heartfield was forced to flee the country. In December he arrived in London. Over the next few months his work appeared in the Reynolds News and Lilliput. He spoke at political rallies, organized anti-Fascist groups, and took part in a successful political cabaret, Four and Twenty Black Sheep. On 23rd September, 1939, Picture Post used one of Heartfield's earlier photomontages, His Majesty Adolf, which showed Hitler wearing the Kaiser's uniform and moustache, on its front-cover.

On the outbreak of the Second World War he was interned with fellow refugees who had suffered under the Nazis and were now dubbed "enemy aliens". He was suffering from poor health and he was eventually released but he was not asked to work for the British government. "His whole ambition was to make people fully aware of the menace of Fascism and to expose the Nazi tyranny through his work as an artist... The powerful contribution he might have made toward the Allied victory through his mastery of satire was not acceptable to the British authorities. They were highly suspicious of art, especially experimental forms of art by a German refugee."

One of John Heartfield most powerful photomontages, This is the Salvation that they Bring!, that had originally been published in protest against the Spanish Civil War, was republished during the Blitz. On the poster it had an extract from an article that appeared in the Nazi Party funded Berlin Journal for Biology and Race Research: "The densely populated sections of cities suffer most acutely in air raids. Since these areas are inhabited for the most part by the ragged proletariat, society will thus be rid of these elements. One-ton bombs not only cause death but also very frequently produce madness. People with weak nerves cannot stand such shocks. That makes it possible for us to find out who the neurotics are. Then the only thing that remains is to sterilize such people. Thereby the purity of the race is guaranteed."

John and his third wife, Gertrud (Tutti) Heartfield, settled in Hampstead. During the war he was an active member of the Artists International Association and contributed to its exhibitions. Heartfield also designed book jackets for the London publisher Lindsay Drummond and Penguin Books.

John Heartfield and his wife moved to Leipzig in East Germany in August 1950. Together with his brother, Wieland Herzfelde, he worked for publishers and organizations in the GDR. He also designed scenery and posters for the Berliner Ensemble and the Deutsches Theatre. However, as Peter Selz has pointed out, he found it difficult to produce political photomontages. "While he was celebrated as a cultural leader, his chief idiom, photomontage, was still suspect during the 1950s among the more orthodox advocates of socialist realism."

Heartfield continued to be a peace activist and on 9th June 1967, at the time of an exhibition of his works at the Stockholm Modern Museum, he wrote about the dangers posed by the Vietnam War. "Since we are living in the nuclear age, a third world war would mean a catastrophe for all mankind, a catastrophe the full extent of which cannot be possibly be imagined.... The war of extermination against the Vietnamese people, fighting heroically for their existence... Now there is a war in the Middle East! Shortly before that, a monarchist-fascist putsch smothered every democratic political movement in Greece. The flames are licking at your doorstep! Today peace-loving men of all nations must work together even more closely; must mobilize all the resources to strengthen and preserve world peace, since powerful rulers again lust for war."

John Heartfield died in Berlin on 26th April, 1968.

become blind and deaf, Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (AIG) (February 1930)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

On this day in 1896 Rajani Palme Dutt, the son of an Indian doctor and a Swedish mother, was born in 1896. Dutt was brought up in Cambridge and educated at The Perse School before winning a place at Balliol College, Oxford.

Dutt was opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War. Over 3,000,000 men volunteered to serve in the British Armed Forces during the first two years of the war. Due to heavy losses at the Western Front the government decided in 1916 to introduce conscription (compulsory enrollment).

As a pacifist Dutt refused to serve in the armed forces. However, he was told conscription "did not apply to him, on racial grounds". He appealed successfully and when he was conscripted he refused to serve and was sentenced to six months in prison. Soon after his release he was expelled from Oxford University for organizing a meeting in support of the Russian Revolution. He was allowed back to take his finals and won a first-class degree, the best of his year.

In 1919 he was made international secretary of the Labour Research Department. A large number of socialists had been impressed with the achievements of the Bolsheviks following the Russian Revolution and in April 1920 several political activists, including Tom Bell, Willie Gallacher, Arthur McManus, Harry Pollitt, Helen Crawfurd and Willie Paul to establish the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). McManus was elected as the party's first chairman and Bell and Pollitt became the party's first full-time workers. Rajani Palme Dutt was one of the first people to join the CPGB.

In 1921 Dutt founded the magazine The Labour Monthly, which he edited for over 50 years. Dutt, along with Harry Pollitt and Hubert Inkpin was charged with the task of implementing the organisational theses of the Comintern. As Jim Higgins has pointed out: "In the streamlined “bolshevised” party that came out of the re-organisation, all three signatories reaped the reward of their work. Inkpin was elected chairman of the Central Control Commission Dutt and Pollitt were elected to the party executive. Thus started the long and close association between Dutt and Pollitt. Palme Dutt, the cool intellectual with a facility for theoretical exposition, with friends in the Kremlin and Pollitt the talented mass agitator and organiser."

Rajani Palme Dutt was also a member of Comintern and was given the task of supervising the Communist Party of India. His wife, Salme Murrik was also a member of the CPGB. In 1936 he replaced Idris Cox as editor of the Daily Worker.

Dutt was a loyal supporter of Joseph Stalin in his attempts to purge the followers of Leon Trotsky in the Soviet Union. In the Daily Worker on 12th March, 1936, Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of the CPGB, argued that the proposed trial of Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Ivan Smirnov and thirteen other party members who had been critical of Stalin represented "a new triumph in the history of progress". Later that year all sixteen men were found guilty and executed.

Dutt used the The Labour Monthly and the Daily Worker to defend the Great Purge. As Duncan Hallas pointed out: "He repeated every vile slander against Trotsky and his followers and against the old Bolsheviks murdered by Stalin through the 1930s, praising the obscene parodies of trials that condemned them as Soviet justice".

Harry Pollitt remained loyal to Joseph Stalin until September 1939 when he welcomed the British declaration of war on Nazi Germany. Stalin was furious with Pollitt's statement as the previous month he had signed the Soviet-Nazi Pact with Adolf Hitler.

At a meeting of the Central Committee on 2nd October 1939, Dutt demanded "acceptance of the (new Soviet line) by the members of the Central Committee on the basis of conviction". He added: "Every responsible position in the Party must be occupied by a determined fighter for the line." Bob Stewart disagreed and mocked "these sledgehammer demands for whole-hearted convictions and solid and hardened, tempered Bolshevism and all this bloody kind of stuff."

William Gallacher agreed with Stewart: "I have never... at this Central Committee listened to a more unscrupulous and opportunist speech than has been made by Comrade Dutt... and I have never had in all my experience in the Party such evidence of mean, despicable disloyalty to comrades." Harry Pollitt joined in the attack: "Please remember, Comrade Dutt, you won't intimidate me by that language. I was in the movement practically before you were born, and will be in the revolutionary movement a long time after some of you are forgotten."

John R. Campbell, the editor of the Daily Worker, thought the Comintern was placing the CPGB in an absurd position. "We started by saying we had an interest in the defeat of the Nazis, we must now recognise that our prime interest in the defeat of France and Great Britain... We have to eat everything we have said."

Harry Pollitt then made a passionate speech about his unwillingness to change his views on the invasion of Poland: "I believe in the long run it will do this Party very great harm... I don't envy the comrades who can so lightly in the space of a week... go from one political conviction to another... I am ashamed of the lack of feeling, the lack of response that this struggle of the Polish people has aroused in our leadership."

However, when the vote was taken, only Harry Pollitt, John R. Campbell and William Gallacher voted against. Pollitt was forced to resign as General Secretary and he was replaced by Dutt and William Rust took over Campbell's job as editor of the Daily Worker. Over the next few weeks the newspaper demanded that Neville Chamberlain respond to Hitler's peace overtures.

On 22nd June 1941 Germany invaded the Soviet Union. That night Winston Churchill said: "We shall give whatever help we can to Russia." The CPGB immediately announced full support for the war and brought back Harry Pollitt as general secretary. Membership increased dramatically from 15,570 in 1938 to 56,000 in 1942.

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Joseph Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. Harry Pollitt found it difficult to accept these criticisms of Stalin and said of a portrait of his hero that hung in his living room: "He's staying there as long as I'm alive".

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprisingan estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar.

Over 7,000 members of the Communist Party of Great Britain resigned over what happened in Hungary. Harry Pollitt responded by resigning as General Secretary of the CPGB. However, Rajani Palme Dutt continued to remain loyal to the Soviet Union and in 1968 disagreed with the the CPGB opposition to the Warsaw Pact intervention in Czechoslovakia.

Rajani Palme Dutt died on 20th December 1974.

On this day in 1896 Wallis Warfield was born in Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania. Her father, Teakle Warfield was an unsuccessful businessman, and his wife, Alice Montague. According to her biographer, Philip Ziegler: "The Warfields and Montagues were of distinguished southern stock, but Wallis's parents were poor relations and her father died when she was only five months old. She spent her childhood in cheese-paring poverty, resentfully aware that her friends could afford nicer clothes and more lavish holidays. It seems reasonable to trace to this early deprivation the acquisitive streak which so strongly marked her character."

In 1916 Wallis met an married Winfield Spencer, a naval aviator. He was a sadistic alcoholic and in 1921 she left him but later agreed to join him in China. According to Paul Foot, " the American state files, produces clear evidence that Wallis Spencer, as she then was, was hired as an agent for Naval Intelligence. The purpose of her visit to China in the mid-Twenties, where she accompanied her husband, who also worked for Intelligence, was to carry secret papers between the American Government and the warlords they supported against the Communists. In Peking her consort for a time was Alberto de Zara, Naval Attaché at the Italian Embassy, whose enthusiasm for Mussolini was often expressed in verse. Wallis’s enthusiasm for the Italian dictatorship was, by this time, the only thing she had in common with her husband, Winfield Spencer."

According to Charles Higham, the author of Wallis: Secret Lives of the Duchess of Windsor (1988), while in Shanghai in 1925, she had an affair with the handsome fascist Count Galeazzo Ciano, who was later to become the son-in-law of Benito Mussolini. The affair resulted in a pregnancy, and a carelessly carried out abortion had left Wallis unable to have any more children. Wallis eventually divorced her husband in 1927.

Wallis then met the divorced businessman, Ernest Simpson.He was a partner in a shipping firm that had close business ties with Fascist Italy. The couple married in 1928 and moved to London. They became friends with Lady Thelma Furness, a mistress of the Prince of Wales. On the 10th January, 1931, Furness invited them to her country house at Melton Mowbray where they met the heir to the throne. Prince Edward was fascinated by Wallis and it was not long before he was having an affair with her.

Colin Matthew has pointed out: "By 1934 the prince had cast aside both Lady Furness and Freda Dudley Ward (the latter cut off without, apparently, any personal farewell). The prince saw Mrs Simpson as his natural companion in life, both sexually and intellectually.... A man accustomed to get his way, when he knew what it was that he wanted, the prince of Wales seems to have thought from 1934 onwards that matters would turn out as he wished. Though he appears from an early stage to have wanted Wallis as his queen, he made no effort to test or prepare the ground, even with those whose support would be vital. Nor do those around him seem to have sounded him as to his intentions (and as his accession was clearly imminent they could not have been blamed if they had done so). Neither the prince's father nor mother seems to have raised with him either the affair or its likely result. Thus the prince of Wales's affair with Mrs Simpson, pursued with a passion evident to all who observed it, occurred in a political and constitutional limbo."

Wallis Simpson left her husband and went to live in an apartment in Bryanston Court. Also living in the building was Princess Stephanie von Hohenlohe. The two women soon became close friends. This was unfortunate for Simpson because of a tip off from French Intelligence, MI6 was intercepting Princess Stephanie's correspondence and tracking her movements in and out of the country since early in 1928.

In December 1932 a number of European newspapers had carried allegations of espionage against Princess Stephanie. The French newspaper, La Liberté, claimed that she had been arrested as a spy while visiting Biarritz. It asked the question: "Is a sensational affair about to unfold?" Other newspapers took up the story and described her as a "political adventuress" and "the vamp of European politics". These stories were probably the result of leaks from the French intelligence services. However, she had not been arrested. According to a 2005 declassified document, the British secret service circulated a government report stating that files had been found in the princess' flat in Paris showing she had been commissioned by the German authorities to persuade Lord Rothermere to campaign in his newspapers for the return to Germany of territory and colonies ceded in the end of the First World War.

In November, 1933, Lord Rothermere gave Princess Stephanie the task of establishing personal contact with Adolf Hitler. Princess Stephanie later recalled: "Rothermere came from a family that had experienced the novel possibility of influencing international politics through newspapers and was determined to sound out Hitler." Stephanie went to Berlin and began a sexual relationship with Captain Fritz Wiedemann, Hitler's personal adjutant. Wiedemann reported back to Hitler that Stephanie was the mistress of Lord Rothermere. Hitler decided that she could be of future use to the government and gave Wiedemann 20,000 Reichsmarks as a maintenance allowance to ensure that she had her hotel, restaurant bills, telephone bills and taxi and travel fares paid. Wiedemann was also allowed to buy her expensive clothes and gifts.

The following month Wiedemann arranged for Princess Stephanie to have her first meeting with Hitler. According to Jim Wilson, the author of Nazi Princess: Hitler, Lord Rothermere and Princess Stephanie Von Hohenlohe (2011): "The Führer appears to have been highly impressed by her sophistication, her intelligence and her charms. At that first meeting she wore one of her most elegant outfits, calculating it would impress him. It seems to have done so, because Hitler greeted her with uncharacteristic warmth, kissing her on the hand. It was far from usual for Hitler to be so attentive to women, particularly women introduced to him for the first time. The princess was invited to take tea with him, and once seated beside him, according to her unpublished memoirs. Hitler scarcely took his piercing eyes off her."

Edward's relationship with Simpson created a great deal of scandal. So also did his political views. In July 1933 Robert Vansittart, a diplomat, recounted in his diary that at a party where there was much discussion about the implications of Hitler's rise to power. "The Prince of Wales was quite pro-Hitler and said it was no business of ours to interfere in Germany's internal affrairs either re- the Jews or anyone else, and added that dictators are very popular these days and we might want one in England." In 1934 he made comments suggesting he supported the British Union of Fascists. According to a Metropolitan Police Special Branch report he had met Oswald Mosley for the first time at the home of Lady Maud Cunard in January 1935.

Paul Foot has argued: "Fascism... fitted precisely with Wallis’s own upbringing, character and disposition. She was all her life an intensely greedy woman, obsessed with her own property and how she could make more of it. She was a racist through and through: anti-semitic, except when she hoped to benefit from rich Jewish friends; and anti-black... She was offensive to her servants, and hated the class they came from."

The government was also aware that Wallis Simpson was in fact involved in other sexual relationships. This included a married car mechanic and salesman called Guy Trundle and Edward Fitzgerald, Duke of Leinster. More importantly, they had evidence that Wallis Simpson was having a relationship with Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German Ambassador to Britain. The FBI definitely believed this was the case and one report suggested that he had sent a bouquet of seventeen red roses to Princess Stephanie's flat in Bryanston Court because each bloom represented an occasion they had slept together.