On this day on 17th February

On this day in 1821 Eliza Gilbert, the daughter of an army officer and a Spanish woman, was born in County Sligo, Ireland. She spent some of her childhood in India but after her father died of cholera the rest of the family moved to Scotland.

In 1832 Eliza was sent to boarding school in Bath. At the age of 16 she eloped with Lieutenant Thomas James. The marriage was not a success and the couple separated five years later. In 1843 Eliza adopted the name Lola Montez and launched a career as a dancer.

Over the next few years Lola Montez worked throughout Europe as a dancer and is believed to have had relationships with the novelist, Alexander Dumas, and the composer, Franz Lizst. After appearing in Munich in 1846 she became the mistress of Ludwig of Bavaria. The following year she was granted the title the Countess of Landsfeld. It was during this time that the expression, "Whatever Lola wants, Lola gets", entered the English language.

In 1848 the Bavarians rose up against their ruler and Ludwig was forced to abdicate. Lola Montez fled the country and emigrated to the United States. Montez married Patrick Hull and with the help of her new husband decided to revive her career as an actress and dancer. In May 1853 she appeared in her own play, Lolo Montez in Bavaria, in San Francisco. The play created a sensation and the the reviewer in the Alta California praised her "peculiar earnestness of manner and utterance, her depth of feeling and power to display the passions of an ardent and high-souled woman."

Montez's performance in Spider Dance was less successful. While in Sacramento she paused in the middle of her performance and lectured the audience on their poor manners. One critic pointed out that this developed into a "torrent of abuse and profanity". After receiving a poor review in the Daily California she challenged the editor to a duel.

Hurt by these comments in the press Montez decided to retire from the stage and purchased a cottage in Grass Valley. This was close to a mining camp that had been established during the Californian Gold Rush. Retirement did not last for long and she was soon performing for local miners. She received good reviews in the Grass Valley Telegraph, but as one critic pointed out, the editor, Henry Shipley, "had not exactly the run of the house on Mill Street, he had at least the privileges of the front door." However, Shipley eventually fell out with Montez and wrote a satirical piece about the two having a duel with "horse-whips, nails and tongue" at the Golden Gate Saloon.

In June 1855 Lola Montez sailed for Australia. After a two year tour she returned to the United States. Later she moved to New York where she became an active member of the Episcopal Church.

Lola Montez died of pneumonia on 17th January, 1861.

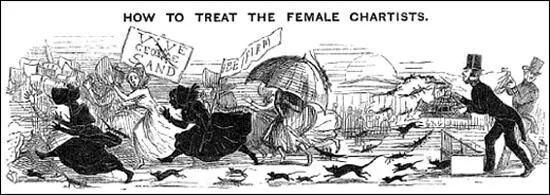

On this day in 1838 The Northern Star reports a speech made by Chartist leader Elizabeth Hanson. Elizabeth told the audience that local women who were living in the workhouse were being forced to wear shoddy clothes and had their hair cropped. Most importantly, they were being separated from their children. Elizabeth suggested that in order to stop this outrage women had to join together to form political organisations.

Elizabeth Hanson was born in 1797. She married Abram Hanson, a shoemaker, who lived in Elland, near Halifax. She had her first child in 1827. Others followed in 1829 and 1834. Elizabeth became politically active after the passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834. The act stated that: (a) no able-bodied person was to receive money or other help from the Poor Law authorities except in a workhouse; (b) conditions in workhouses were to be made very harsh to discourage people from wanting to receive help; (c) workhouses were to be built in every parish or, if parishes were too small, in unions of parishes.

Elizabeth was furious that the legislation "cast women in the role of dependants on their husbands' incomes rather than as contributors to the family income on their own right". Elizabeth had three children and none were yet contributing to the family's income and saw the legislation as a "major assault on the integrity of the family".

Abram Hanson became one of the most important Chartist leaders in the area. In one speech he launched an attack on the clergy of every denomination: "They preached Christ and a crust, passive obedience and non-resistance. Let the people keep from those churches and chapels. Let them go to those men who preached Christ and a full belly, Christ and a well-clothed back - Christ and a good house to live in - Christ and Universal Suffrage."

Elizabeth Hanson and Mary Grassby, formed the Elland Female Radical Association in March, 1838. She argued "it is our duty, both as wives and mothers, to form a Female Association, in order to give and receive instruction in political knowledge, and to co-operate with our husbands and sons in their great work of regeneration." She became one of the movement's most effective speakers and one newspaper reported she "melted the hearts and drew forth floods of tears".

Elizabeth and her fellow members attempted to improve their political knowledge by attending evening-classes. The Leeds Times reported: "The Ellanders seem determined not to wait the time of government appointments for national education, but to begin to educate themselves."

In 1839 Elizabeth gave birth to a son, who she named after Feargus O'Connor. She continued to be involved in the campaign for universal suffrage. Abram Hanson acknowledged the importance of "the women who are the best politicians, the best revolutionists, and the best political economists... should the men fail in their allegiance the women of Elland, who had sworn not to breed slaves, had registered a vow to do the work of men and women."

Elizabeth and Abram sustained "a close and affectionate relationship" and although he frequented "the public house too much" the couple "managed to bring a family up in decency, considering his station in life". After 1840 Elizabeth was less active in the Chartist movement. This was probably because of having a very young son to look after. However, as late as 1852 Elizabeth was sending small donations to Chartist causes.

On this day in 1870 William Edward Forster introduces his Education bill to the House of Commons. After the passing of the 1867 Reform Act, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Robert Lowe, remarked that the government would now "have to educate our masters." As a result of this view, the government passed the 1870 Education Act. It stated:

(a) the country would be divided into about 2500 school districts;

(b) School Boards were to be elected by ratepayers in each district;

(c) the School Boards were to examine the provision of elementary education in their district, provided then by Voluntary Societies, and if there were not enough school places, they could build and maintain schools out of the rates;

(d) the school Boards could make their own by-laws which would allow them to charge fees or, if they wanted, to let children in free.

The 1870 Education Act allowed women to vote for the School Boards. Women were also granted the right to be candidates to serve on the School Boards. Several feminists saw this as an opportunity to show they were capable of public administration. In 1870, four women, Lydia Becker, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett and Flora Stevenson, were elected to local School Boards. Garrett, a popular local doctor, obtained more votes Marylebone than any other candidate in the country.

On this day in 1871 Julia O'Sullivan was born in Limehouse on 17th February 1873. Her father was John O'Sullivan, an immigrant from Cork.

Julia married John Scurr in Woolwich in 1899. The couple had two sons and a daughter. At the time her husband was an active member of the Social Democratic Federation, and was associated with people such as H. M. Hyndman, Tom Mann, John Burns, Eleanor Marx, George Lansbury, Edward Aveling, H. H. Champion, Helen Taylor, Guy Aldred, John Spargo and Ben Tillet.

In 1905 Julia joined forces with James Keir Hardie, Dora Montefiore, George Lansbury to organise a deputation on unemployment of 1,000 women to meet the Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour. During this period she also became active in the struggle for women's suffrage and worked very closely with Sylvia Pankhurst.

In 1907 Julia Scurr became a member of to the Board of Guardians that ran the Poplar Workhouse. Working closely with George Lansbury she presented a report criticizing the lack of Day Rooms and recreational space at the Bow Infirmary.

In 1913, Sylvia Pankhurst, with the help of Julia Scurr, Millie Lansbury, Keir Hardie and George Lansbury, established the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party. As June Hannam has pointed out: "The ELF was successful in gaining support from working women and also from dock workers. The ELF organized suffrage demonstrations and its members carried out acts of militancy. Between February 1913 and August 1914 Sylvia was arrested eight times.... She also drew on East End traditions by calling for rent strikes to support the demand for the vote."

On 6th February 1914 a group of supporters of women's suffrage, who were disillusioned by the lack of success of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and disapproval of the arson campaign of the Women Social & Political Union, decided to form the United Suffragists movement. Membership was open to both men and women, militants and non-militants. Members included Julia Scurr, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Evelyn Sharp, Henry Nevinson, Margaret Nevinson, Hertha Ayrton, Israel Zangwill, Edith Zangwill, Lena Ashwell, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, John Scurr and Laurence Housman.

Julia Scurr led a deputation of East End women to see Prime Minister Henry Asquith in June 1914 to protest about the low wages being paid to women. She told him: "Any rise in the price of rents, foods and other household commodities affects us women vitally... The position of working-class women is one that we all feel deeply. Our husbands die on the average at a much earlier age than do the men of other classes. Modern industrialism kills them off rapidly both by accident and by overwork... we are left often with a family of young children to support... The Poor Law has treated us mercilessly. It is hated by every poor woman. In many cases outdoor relief is altogether denied to the widow, as it is to the deserted wife, and only the Workhouse is offered, which means separation from the children."

In November 1919 Julia Scurr was elected to Poplar Council. The Labour Party had won 39 of the 42 council seats. In 1921 Poplar had a rateable value of £4m and 86,500 unemployed to support. Whereas other more prosperous councils could call on a rateable value of £15 to support only 4,800 jobless. George Lansbury proposed that the Council stop collecting the rates for outside, cross-London bodies. This was agreed and on 31st March 1921, Poplar Council set a rate of 4s 4d instead of 6s 10d. On 29th the Councillors were summoned to Court. They were told that they had to pay the rates or go to prison. At one meeting Millie Lansbury said: "I wish the Government joy in its efforts to get this money from the people of Poplar. Poplar will pay its share of London's rates when Westminster, Kensington, and the City do the same."

On 28th August over 4,000 people held a demonstration at Tower Hill. The banner at the front of the march declared that "Popular Borough Councillors are still determined to go to prison to secure equalisation of rates for the poor Boroughs." The Councillors were arrested on 1st September. Five women Councillors, including Julia, Millie Lansbury and Susan Lawrence, were sent to Holloway Prison. Twenty-five men, including George Lansbury and John Scurr, went to Brixton Prison. On 21st September, public pressure led the government to release Nellie Cressall, who was six months pregnant. Julia Scurr reported that the "food was unfit for any human being... fish was given on Friday, they told us, that it was uneatable, in fact, it was in an advanced state of decomposition".

Instead of acting as a deterrent to other minded councils, several Metropolitan Borough Councils announced their attention to follow Poplar's example. The government led by Stanley Baldwin and the London County Council was forced to back down and on 12th October, the Councillors were set free. The Councillors issued a statement that said: "We leave prison as free men and women, pledged only to attend a conference with all parties concerned in the dispute with us about rates... We feel our imprisonment has been well worth while, and none of us would have done otherwise than we did. We have forced public attention on the question of London rates, and have materially assisted in forcing the Government to call Parliament to deal with unemployment."

In the 1923 General Election, John Scurr, Susan Lawrence and George Lansbury were all elected to the House of Commons.The Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions".

On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. MacDonald had not been fully supportive of the Poplar Councillors since he thought that "public doles, Popularism, strikes for increased wages, limitation of output, not only are not Socialism but may mislead the spirit and policy of the Socialist movement." George Lansbury was therefore not offered a post in his Cabinet.

John Wheatley, the new Minister of Health, had been a supporter of the Poplar Councillors. Edgar Lansbury wrote in The New Leader that he was sure that Wheatley would "understand and sympathise with them in this horrible problem of poverty, misery and distress which faces them." Lansbury's assessment was correct and as Janine Booth, the author of Guilty and Proud of It! Poplar's Rebel Councillors and Guardians 1919-25 (2009), has pointed out: "Wheatley agreed to rescind the Poplar order. It was a massive victory for Poplar, whose guardians had lived with the threat of legal action for two years and were finally vindicated."

Julia Scurr died on 10th April 1927 at the age of 57. George Lansbury wrote that he had no doubt that the period of imprisonment, and the treatment she received, was directly responsible for her death.

On this day in 1880 Stefan Khalturin attempts to assassinate Tsar Alexander II. In November 1879 Khalturin managed to find work as a carpenter in the Winter Palace. According to Adam Bruno Ulam, the author of Prophets and Conspirators in Pre-Revolutionary Russia (1998): "There was, incomprehensible as it seems, no security check of workman employed at the palace. Stephan Khalturin, a joiner, long sought by the police as one of the organizers of the Northern Union of Russian workers, found no difficulty in applying for and getting a job there under a false name. Conditions at the palace, judging from his reports to revolutionary friends, epitomized those of Russia itself: the outward splendor of the emperor's residence concealed utter chaos in its management: people wandered in and out, and imperial servants resplendent in livery were paid as little as fifteen rubles a month and were compelled to resort to pilfering. The working crew were allowed to sleep in a cellar apartment directly under the dining suite."

Khalturin approached George Plekhanov about the possibility of using this opportunity to kill Tsar Alexander II. He rejected the idea but did put him in touch with the People's Will who were committed to a policy of assassination. It was agreed that Khalturin should try and kill the Tsar and each day he brought packets of dynamite, supplied by Anna Yakimova and Nikolai Kibalchich, into his room and concealed it in his bedding. Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976), has argued: "His workmates regarded him as a clown and a simpleton and warned him against socialists, easily identifiable apparently for their wild eyes and provocative gestures. He worked patiently, familiarizing himself with the Tsar's every movement, and by mid-January Yakimova and Kibalchich had provided him with a hundred pounds of dynamite, which he hid under his bed."

On 17th February, 1880, Khalturin constructed a mine in the basement of the building under the dinning-room. The mine went off at half-past six at the time that the People's Will had calculated Alexander II would be having his dinner. However, his main guest, Prince Alexander of Battenburg, had arrived late and dinner was delayed and the dinning-room was empty. Alexander was unharmed but sixty-seven people were killed or badly wounded by the explosion.

Stefan Khalturin moved away from St. Petersburg and in March, 1882, he was captured while engaged in another assassination plot against the Governor-General of Odessa. He was executed a few days later.

On this day in 1889 Haroldson Lafayette Hunt, was born in Fayette County, Illinois. After a brief formal education he went travelling. In 1912 he settled in Arkansas, where he ran a cotton plantation.

In 1921 Hunt moved to El Dorado where he became a lease broker. He eventually discovered oil and by 1925 was extremely wealthy. He suffered some business reverses but in 1930 he obtained his own pipeline, the Panola, to run oil from the East Texas field. Two years later Hunt Production Company had 900 wells in East Texas.

Hunt established the Placid Oil Company in 1935. The following year he acquired the Excelsior Refining Company in Rusk County and changed the name to Parade Refining Company. He also established his headquarters in Dallas, Texas. In 1948 a newspaper reported that Hunt was the richest man in the United States. It estimated the value of his oil properties at $263 million and the daily production of crude from his wells at 65,000 barrels.

Hunt developed extreme conservative political opinions. In 1951 he launched the Douglas MacArthur for President campaign. Along with two of his sons, Nelson Bunker Hunt and Lamar Hunt, he set-up a right-wing intelligence network, the International Committee for the Defence of Christian Culture.

Hunt also funded two right-wing radio shows, Facts Forum and Life Line. He used these radio stations to support the anti-communist campaign of Joseph McCarthy. He also helped to finance the political career of Lyndon B. Johnson. A member of the John Birch Society, Hunt was a close friend of Edwin Walker.

A strong opponent of Fidel Castro, Hunt helped to fund the Cuban Revolutionary Council, a group that worked with the Mafia and the Central Intelligence Agency in an effort to remove Castro from power.

President John F. Kennedy became concerned about people like Hunt who used tax exemptions to spread right-wing propaganda. According to Joachim Joesten Hunt had an annual income of $30,000,000 but paid little in income tax. In 1963 Kennedy talked about plans to submit to Congress a tax reform plan designed to produce about $185,000,000 in additional revenues by changes in the favourable tax treatment until then accorded the gas-oil industry.

Some conspiracy theorists believe that Hunt was involved in the death of President John F. Kennedy. It was claimed that the day before the assassination, Jim Brading visited Hunt in his office in Dallas. Brading had links to Carlos Marcello, another figure suspected of being involved in the killing. Brading was arrested in the Dal-Tex building in the Dealey Plaza soon after the assassination took place, but was released soon afterwards.

Madeleine Brown later gave an interview on the television show, A Current Affair where she claimed that on the 21st November, 1963, she was at the home of Clint Murchison. Others at the meeting included Hunt, J. Edgar Hoover, Clyde Tolson, John J. McCloy and Richard Nixon. At the end of the evening Lyndon B. Johnson arrived. Brown said in this interview: "Tension filled the room upon his arrival. The group immediately went behind closed doors. A short time later Lyndon, anxious and red-faced, reappeared. I knew how secretly Lyndon operated. Therefore I said nothing... not even that I was happy to see him. Squeezing my hand so hard, it felt crushed from the pressure, he spoke with a grating whisper, a quiet growl, into my ear, not a love message, but one I'll always remember: "After tomorrow those goddamn Kennedys will never embarrass me again - that's no threat - that's a promise."

Brown's account was supported by former CIA agent Robert D. Morrow who wrote in the book, First Hand Knowledge: How I participated in the CIA-Murder of President Kennedy, "On the eve of the assassination, Hoover and Nixon attended a meeting together at the Dallas home of oil baron Clint Murchison. Among the subjects discussed at this meeting were the political futures of Hoover and Nixon in the event President Kennedy was assassinated."

Haroldson Lafayette Hunt, who was married three times and fathered 14 children, died on 29th November, 1974.

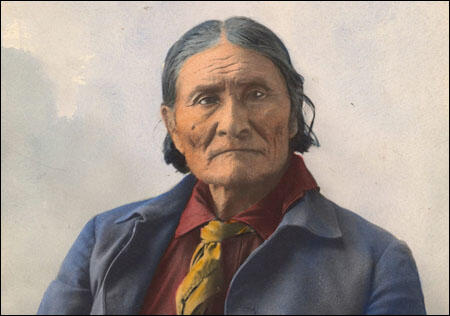

On this day in 1909 Geronimo died at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Geronimo, a member of the Bedonkohe Apache tribe, was born in Arizona in 1823. His original name was Goyahkla (He Who Yawns). Mangas Coloradas and the Bedonkohe moved to Janos. In 1850, while the men were away, the Mexicans killed the camp's women and children. This included Geronimo's mother, his wife and three children. During the revenge attacks that took place on the Mexicans he was given the name of Geronimo.

Geronimo became a war leader and in 1858 Geronimo and his warriors won a great victory at Namaquipa. The discovery of gold at Pinos Altos, New Mexico, increased the number of Americans travelling through Apache land. This resulted in attacks by war chiefs such as Geronimo and Cochise. This included the attack at Apache Pass on 14th July, 1862.

In 1876 the American government ordered the Chiricahuas from their mountain homeland to the San Carlos Reservation. Geronimo refused to go and over the next few years he led a small band of warriors that raided settlements in Arizona. Geronimo also attacked American troops in the Whetstone Mountains, Arizona, on 9th January, 1877. This was followed by a rare defeat in the Leitendorf Mountains.

Geronimo was captured when entering the Ojo Caliente Reservation in New Mexico. Geronimo was eventually released and by April 1878 he was leading war parties in Mexico. The following year Geronimo surrendered and settled on the San Carlos Reservation. However, in 1881 Juh and Geronimo and their people left the reservation and headed for the Sierra Madre. In 1882 they carried out their most ambitious raid of all when they attacked San Carlos.

After the death of Juh, Geronimo became the leader of the Apache warriors. He continued to carry out raids until he took part in peace talks with General George Crook. Crook was criticized for the way he was dealing with the situation and as a result he asked to be relieved of his command.

General Nelson Miles replaced Crook and attempted to defeat Geronimo by military means. This strategy was also unsuccessful and eventually he resorting to Crook's strategy of offering a negotiated deal. In September 1886 Geronimo signed a peace treaty with Miles and the last of the Indian Wars was over.

Geronimo and his people were taken to Florida and Alabama before eventually settling in Oklahoma. Ace Daklugie and S. M. Barrett worked with Geronimo on his autobiography, Geronimo's Story of His Life in 1906.

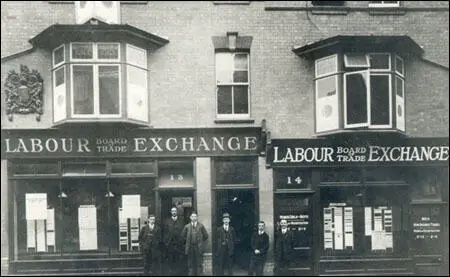

On this day in 1909 Winston Churchill announces the formation of labour exchanges. In the midst of the worst recession since 1879, the Government was under increasing pressure to take some action to deal with unemployment and the labour market. William Beveridge proposed a national scheme of labour exchanges. It was based on the system used in Germany whose 4,000 exchanges that filled over one million jobs a year. Churchill shared Beveridge's passion for efficiency and a hatred of waste and his views on the working class. Beveridge told his brother-in-law, R. H. Tawney: "The well-to-do represent on the whole a higher level of character and ability than the working class because in the course of time the better stocks have come to the top. A good stock is not permanently kept down: it forces its way up in the course of generations of social change, and so the upper classes are on the whole the better classes."

Winston Churchill told the Cabinet that labour exchanges would not in themselves create more jobs. The exchanges were viewed as a way of improving the efficiency of the industrial system, providing "intelligence" about the state of industry and saving economic waste through the more efficient use of labour. It was also hoped that exchanges would have a social and moral function since they would, as Churchill predicted "enable the idle vagrant to be discovered unmistakably and sent to an institution for disciplinary detention."

The proposal for creating labour exchanges was announced on 17th February 1909. There would be a network of several hundred exchanges as part of a national reporting system on the labour market. The trade union movement initially opposed the scheme as they feared that labour exchanges would be used to break strikes. The only concession he made to the unions was that a man would not to be penalised for refusing to accept a job at less than union rates. He told the Engineering Employers Association: "If anybody had said a year ago that the trades unions would have agreed to a government labour exchange sending 500 or 1,000 men to an employer whose men are out on strike... nobody would have believed it all."

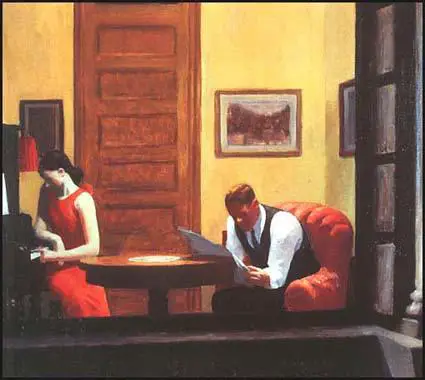

On this day in 1913 the work of Edward Hopper is exhibited for the first time. Edward Hopper, the son of an owner of a dry-goods store, was born in Nyack on 22nd June 1882. He registered with the Correspondence School of Illustrating in 1899. He studied under Robert Henri and William Merritt Chase at the New York School of Art from 1900 to 1906. A fellow student was George Bellows.

In 1913 the ideas of Henri inspired the International Exhibition of Modern Art (the Armory Show) held in New York City. Some of Hopper's work was included in the exhibition held at the 69th Regiment Armory. It included over 1,300 works, including 430 from Europe. The exhibition, held between 17th February and 15th March, received around 250,000 visitors.

On this day in 1913 Zelie Emerson and Sylvia Pankhurst are arrested for breaking windows of a branch of Westminster Bank in Bow Road. This was followed by damaging the greens of Bradford Moor golf course. The magistrate said that if the women behaved as "common riffraff" then they must be treated as such and they were both sentenced to two months' hard labour.

Zelie and Sylvia served their sentence in Brixton Prison. They went on hunger and thirst strike and were placed in the hospital wing and force-fed. Sylvia was released after five weeks. During her time in prison she had been force-fed for a month. Zelie was kept in prison for seven weeks although she had appendicitis.

Sylvia was allowed to visit Zelie: "She was ill and asking for me. They hoped that I might quiet her. I knew by the dry, burning touch of her skin that she had fever. She complained of terrible abdominal pain. Shocked at her condition, I took her in my arms, uttering foolish words: 'Oh, my little sweetheart! Oh, my little sweetheart!' Her wrist was bandaged. She told me she had tried to commit suicide by cutting an artery. She had dug into the flesh with her small, blunt penknife, till she reached the artery, but when she had tried to cut it, she found it, she said, too tough, and like an India-rubber band. They had come to the cell while she was working at it."

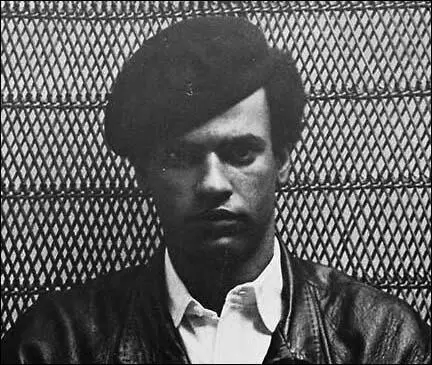

On this day in 1942 Huey Newton was born. Huey Newton, the youngest of seven children, was born in Monroe, Louisiana, on 17th February, 1942. His father, who named his son after the radical politcian, Huey P. Long, was an active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP).

At Merritt College in Oakland, California, Newton met Bobby Seale and in 1966 they formed the Black Panther Party. Initially established to protect local communities from police brutality and racism, it eventually developed into a Marxist revolutionary group. The Black Panthers also ran medical clinics and provided free food to school children. Other important members included Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, Fred Hampton, Bobby Hutton and Eldridge Cleaver.

The activities of the Black Panthers came to the attention of J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. Hoover described the Panthers as "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country" and in November 1968 ordered the FBI to employ "hard-hitting counter-intelligence measures to cripple the Black Panthers".

The Black Panthers had chapters in several major cities and had a membership of over 2,000. Harassed by the police, members became involved in several shoot-outs. This included an exchange of fire between Panthers and the police at Oakland on 28th October, 1967. Newton was wounded and while in hospital was charged with killing a police officer. The following year he was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter.

After being released from prison Newton renounced political violence. Over a six year period 24 Black Panthers had been killed in gun fights with the police. Another member, George Jackson, was killed while in San Quentin prison in August, 1971.

Newton now concentrated on socialist community programs including free breakfasts for children, free medical clinics and helping the homeless. The Panthers also became involved in conventional politics and in 1973 Bobby Seale ran for mayor of Oakland and came second out of nine candidates with 43,710 votes (40 per cent of votes cast).

Newton published his book, Revolutionary Suicide in 1973. The following year he was arrested and charged with murder and assault with a deadly weapon. Released on bail, Newton fled to Cuba but in 1977 he returned to the United States and was freed after two hung juries.

Newton returned to his studies at the University of California Santa Cruz and in 1980 he received a Ph.D. in social philosophy. His dissertation was entitled: War Against the Panthers: A Study in Repression in America.

Huey Newton came into conflict with Tyrone Robinson, a drug-dealer in Oakland. On 22nd August, 1989, Robinson pulled a gun on Newton. It is claimed that Newton's last words were, "You can kill my body, but you can't kill my soul. My soul will live forever!" He was then shot three times in the face by Robinson.

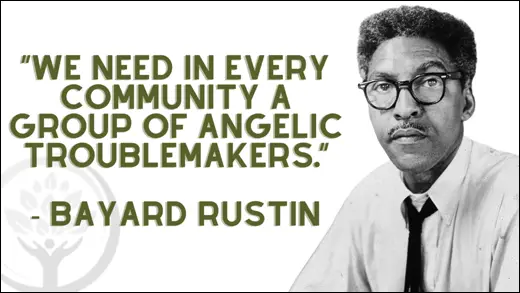

On this day in 1944 Baynard Rustin was sentenced to three years in Lewisburg Penitentiary for refusing to join the United States Army.

Rustin was born in West Chester on 17th March, 1910. For the first ten years of his life he thought that Janifer Rustin and Julia Rustin were his parents. In fact they were his grandparents and his real parents were Archie Hopkins and Florence Rustin, the woman he thought was his sister. Florence was only seventeen and unmarried when she gave birth to Bayard.

Rustin was influenced by the religious and political beliefs of his grandmother, Julia Rustin. A pacifist, Julia was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) and some of its leaders, such as William Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson, sometimes stayed with the family while on their tours of the country.

As a young man Rustin campaigned against Jim Crow laws in West Chester. One of his school friends later said: "Some of us were ready to give up the fight and accept the status quo, but he never would. He had a strong inner spirit."

In 1932, Rustin entered Wilberforce University. Founded by white methodists in 1856 for the benefit of African Americans, the university was named after William Wilberforce, one of the British leaders of the campaign against the slave-trade. However, he left in 1936 without taking his final exams.

Rustin moved to Harlem and began studying at New York City College. He soon became involved in the campaign to free the nine African Americans that had been falsely convicted for raping two white women on a train. Known as the Scottsboro Case, Rustin was radicalized by what he believed was an obvious case of white racism. It was at this time (1936) that Rustin joined the American Communist Party. As Rustin later pointed out, "the communists were passionately involved in the civil rights movement so they were ready-made for me."

Rustin had a fine voice and sung in local folk clubs with Josh White. In September, 1939, Rustin was recruited by Leonard De Paur to appear with Paul Robeson in the Broadway musical, John Henry. However, the show was not a success and closed after a fortnight.

In 1941 Rustin met the African American trade union leader, Philip Randolph. A member of the Socialist Party, Randolph was a strong opponent of communism and as a result of his influence, Ruskin left the American Communist Party in June, 1941.

Rustin helped Philip Randolph plan a proposed March on Washington in June, 1941, in protest against racial discrimination in the armed forces. The march was called off when Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 barring discrimination in defence industries and federal bureaus (the Fair Employment Act).

Abraham Muste, executive secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), who had also been involved in planning the March on Washington was impressed by Rustin's organizational abilities. In September, 1941, Muste appointed Rustin as FOR's secretary for student and general affairs.

In 1942, three members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, Rustin, George Houser and James Farmer, founded the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). Members of this group were pacifists who had been deeply influenced by Henry David Thoreau and his theories on how to use nonviolent resistance to achieve social change. The group were also inspired by the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign that he used successfully against British rule in India. The students became convinced that the same methods could be employed by blacks to obtain civil rights in America.

As a pacifist, Rustin refused to serve in the armed forces. On 12th January, 1944, Rustin was arrested and charged with violating the Selective Service Act. At his trial on 17th February, he was found guilty and sentenced to three years in Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary. Other members of Congress on Racial Equality, including George Houser, Igal Roodenko and James Peck, were also imprisoned during the Second World War for refusing to join the United States Army.

While serving his sentence, Rustin organized protests against segregated seating in the dinning hall. He explained his actions in a letter to E. G. Hagerman, the prison warden: "Both morally and practically, segregation is to me a basic injustice. Since I believe it to be so, I must attempt to remove it. There are three ways in which one can deal with an injustice. (a) One can accept it without protest. (b) On can seek to avoid it. (c) One can resist the injustice non-violently. To accept it is to perpetuate it."

Rustin was released from prison on 11th June, 1946. He immediately joined with George Houser in planning a campaign against segregated transport. In early 1947, CORE announced plans to send eight white and eight black men into the Deep South to test the Supreme Court ruling that declared segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional. The Journey of Reconciliation, as it became known, was to be a two week pilgrimage through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky.

Although Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) was against this kind of direct action, he volunteered the service of its southern attorneys during the campaign. Thurgood Marshall, head of the NAACP's legal department, was strongly against the Journey of Reconciliation and warned that a "disobedience movement on the part of Negroes and their white allies, if employed in the South, would result in wholesale slaughter with no good achieved."

The Journey of Reconciliation began on 9th April, 1947. The team included Bayard Rustin, Igal Roodenko, George Houser, James Peck, Joseph Felmet, Nathan Wright, Conrad Lynn, Wallace Nelson, Andrew Johnson, Eugene Stanley, Dennis Banks, William Worthy, Louis Adams, Worth Randle and Homer Jack.

James Peck was arrested with Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson in Durham. After being released he was arrested once again in Asheville and charged with breaking local Jim Crow laws. In Chapel Hill Peck and four other members of the team was dragged off the bus and physically assaulted before being taken into custody by the local police.

Members of the Journey of Reconciliation team were arrested several times. In North Carolina, two of the African Americans, Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson, were found guilty of violating the state's Jim Crow bus statute and were sentenced to thirty days on a chain gang. However, Judge Henry Whitfield made it clear he found that behaviour of the white men even more objectionable. He told Igal Roodenko and Joseph Felmet: "It's about time you Jews from New York learned that you can't come down her bringing your niggers with you to upset the customs of the South. Just to teach you a lesson, I gave your black boys thirty days, and I give you ninety."

The Journey of Reconciliation achieved a great deal of publicity and was the start of a long campaign of direct action by the Congress of Racial Equality. In February 1948 the Council Against Intolerance in America gave Rustin and George Houser the Thomas Jefferson Award for the Advancement of Democracy for their attempts to bring an end to segregation in interstate travel.

After the arrest of Rosa Parks in December, 1955, after she had refused to give up her seat to a white man, Martin Luther King, a pastor at the local Baptist Church, decided to organize a protest against bus segregation. It was decided that from 5th December, black people in Montgomery would refuse to use the buses until passengers were completely integrated. Rustin was asked to go to Montgomery to help organize this campaign.

Martin Luther King was arrested and his house was fire-bombed. Others involved in the Montgomery Bus Boycott also suffered from harassment and intimidation, but the protest continued. For thirteen months the 17,000 black people in Montgomery walked to work or obtained lifts from the small car-owning black population of the city. Eventually, the loss of revenue and a decision by the Supreme Court forced the Montgomery Bus Company to accept integration and the boycott came to an end on 20th December, 1956.

Baynard Rustin was now King's main adviser and together they formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The new organisation was committed to using nonviolence in the struggle for civil rights, and SCLC adopted the motto: "Not one hair of one head of one person should be harmed." Rustin was offered the job as director of SCLC but he declined as he preferred a more flexible role in the civil rights movement.

In 1963 Rustin began organizing what became known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Rustin was able to persuade the leaders of all the various civil rights groups to participate in the planned protest meeting at the Lincoln Memorial on 28th August.

The decision to appoint Rustin as chief organizer was controversial. Roy Wilkins of the NAACP was one of those who was against the appointment. He argued that being a former member of the American Communist Party made him an easy target for the right-wing press. Although Rustin had left the party in 1941, he still retained his contacts with its leaders such as Benjamin Davis.

Wilkins also feared that the fact that Rustin had been imprisoned several times for both refusing to fight in the armed forces and for acts of homosexuality, would be used against him in the days leading up to the march. However, Martin Luther King and Philip Randolph insisted that he was the best person for the job.

Wilkins was right to be concerned about a possible smear campaign against Rustin. Edgar Hoover, head of the Federal Bureau of Investigations, had been keeping a file on Rustin for many years. An FBI undercover agent managed to take a photograph of Rustin talking to King while he was having a bath. This photograph was then used to support false stories being circulated that Rustin was having a homosexual relationship with King.

This information was now passed on to white politicians in the Deep South who feared that a successful march on Washington would persuade President Lyndon B. Johnson to sponsor a proposed new civil rights act. Storm Thurmond led the campaign against Rustin making several speeches where he described him as a "communist, draft dodger and homosexual".

Most newspapers condemned the idea of a mass march on Washington. An editorial in the New York Herald Tribune warned that: "If Negro leaders persist in their announced plans to march 100,000-strong on the capital they will be jeopardizing their cause. The ugly part of this particular mass protest is its implication of unconstrained violence if Congress doesn't deliver."

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on 28th August, 1963, was a great success. Estimates on the size of the crowd varied from between 250,000 to 400,000. Speakers included Philip Randolph (AFL-CIO), Martin Luther King (SCLC), Floyd McKissick (CORE), John Lewis (SNCC), Roy Wilkins (NAACP), Witney Young (National Urban League) and Walter Reuther (AFL-CIO). King was the final speaker and made his famous I Have a Dream speech.

Rustin was highly valued by the trade union movement, and when the AFL-CIO decided in 1965 to fund a new civil rights organisation, the Philip Randolph Institute, he was asked to be its leader. Named after his close friend, Philip Randolph, Rustin worked for the organization until 1979.

In his final years Rustin was active in the protests against the Vietnam War and in the gay rights movement. In 1986 he claimed: "The barometer of where one is on human rights questions is no longer the black community, it's the gay community. Because it is the community which is most easily mistreated."

Baynard Rustin died in New York on 24th August, 1987.