On this day on 12th November

On this day in 1533 Eustace Chapuys commented on Elizabeth Barton and the dangers she posed to Henry VIII. Barton was born in about 1506. Very little is known about her early life or family. Barton is unlikely to have received any sort of formal education during her childhood, and she was almost certainly illiterate. In 1525 she was a servant in the household of a certain Thomas Cobb, farm manager to Archbishop William Warham, at Goldwell House in the village of Aldington, some 20 miles from Canterbury.

Barton began to suffer from an unknown ailment. Edward Thwaites reported that in 1525 she became seriously ill: "It happened a certain maiden named Elizabeth Barton... to be touched with a great infirmity in her body, which did ascend at diverse times up into her throat, and swelled greatly, during the time whereof she seemed to be in grievous pain, in so much as a man would have thought that she had suffered the pangs of death itself, until the disease descended and fell down into the body again."

According to Barton's biographer, Diane Watt: "In the course of this period of sickness and delirium she began to demonstrate supernatural abilities, predicting the death of a child being nursed in a neighbouring bed. In the following weeks and months the condition from which she suffered, which may have been a form of epilepsy, manifested itself in seizures (both her body and her face became contorted), alternating with periods of paralysis. During her death-like trances she made various pronouncements on matters of religion, such as the seven deadly sins, the ten commandments, and the nature of heaven, hell, and purgatory. She spoke about the importance of the mass, pilgrimage, confession to priests, and prayer to the Virgin and the saints."

In 1526 Barton entered St Sepulchre's Nunnery. Elizabeth had meetings with Edward Bocking, a monk at Christchurch Priory. According to Barton's biographer, Edward Thwaites, "Elizabeth Barton advanced, from the condition of a base servant to the estate of a glorious nun." Thwaites claimed a crowd of about 3,000 people attended one of the meetings where she told of her visions. (4) Other sources say it was 2,000 people. Sharon L. Jansen points out: "In either case there was a sizable gathering at the chapel, indicating something of how quickly and widely reports of her visions had spread."

Bishop Thomas Cranmer was one of those who saw Barton. He wrote a letter to Hugh Jenkyns explaining that he had seen "a great miracle" that had been created by God: "Her trance lasted... the space of three hours and more... Her face was wonderfully disfigured, her tongue hanging out... her eyes were... in a manner plucked out and laid upon her cheeks... a voice was heard... speaking within her belly, as it had been in a cask... her lips not greatly moving.... When her belly spoke about the joys of heaven... it was in a voice... so sweetly and so heavenly that every man was ravished with the hearing thereof... When she spoke of hell... it put the hearers in great fear."

Gradually she began to experience revelations of a controversial character. Elizabeth, now known as the Nun of Kent, was taken to see Archbishop William Warham and Bishop John Fisher. On 1st October 1528, Warham wrote to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey recommending her as "a very well-disposed and virtuous woman". He told of how "she had revelations and special knowledge from God in certain things concerning my Lord Cardinal (Wolsey) and also the King's Highness".

Archbishop Warham arranged a meeting between Elizabeth Barton to see Cardinal Wolsey. She told him that she had seen a vision of him with three swords - one representing his power as Legate (the representative of the Pope), the second his power as Lord Chancellor, and the third his power to grant Henry VIII a divorce from Catherine of Aragon.

Wolsey arranged for Elizabeth Barton to see the King. She told him to burn English translations of the Bible and to remain loyal to the Pope. Elizabeth then warned the King that if he married Anne Boleyn he would die within a month and that within six months the people would be struck down by a great plague. He was disturbed by her prophesies and ordered that she be kept under observation. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer commented later that Henry put off his marriage to Anne because "of her visions". William Tyndale was less convinced by her trances and claimed that her visions were either feigned or the work of the devil.

It is claimed that Edward Bocking encouraged her to speak out against religious reformers inspired by the writings of Martin Luther. "Bocking... is said to have induced her to declare herself an inspired emissary for the overthrow of Protestantism and the prevention of the divorce of Queen Catherine.... There is little doubt that he was her chief instigator in the continuance of her career of deception. His share in the affair, though it cannot be excused, must be ascribed to a mistaken zeal for the preservation of the ancient Faith."

However, Bocking's biographer, Ethan H. Shagan, has claimed that his role in this is not conclusive. "Barton... turned to politics, agitating against Henry VIII's plan to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, and from the beginning of these activities Bocking was her closest confidant. His most important role, however, was as a publicist for Barton. He was often accused, both by Henry VIII's government and by later historians, of having concocted rather than merely disseminated her revelations. It is impossible to tell whether there is substance in the charge but it has the appearance of misogyny, and certainly the government benefited greatly by using it to undermine the commonplace assumption that Barton's revelations must have been holy because a woman could not normally have had the wits to invent them on her own."

Gertrude Courtenay, Marchioness of Exeter, travelled from her house in Kew to Canterbury, in disguise, to consult with Barton. As Sharon L. Jansen, the author of Dangerous Talk and Strange Behaviour: Women and Popular Resistance to the Reforms of Henry VIII (1996) has pointed out: "The Courtenays, along with the Nevilles and the Poles, were the last Yorkist claimants to the English throne; the contact between Gertrude Courtenay and Elizabeth Barton was thus dangerous to both of them."

Father Hugh Rich, a Observant Friar of Richmond, a passionate supporter of Catherine of Aragon, encouraged her to meet Elizabeth Barton. However, she sensibly refused as she feared she would be accused of being involved in a conspiracy against the King. Alison Weir has argued that Barton was "fortunate that for the time being the authorities were prepared to dismiss her as a harmless lunatic; nor did they molest her when she persisted in repeating her prophecies and threats."

Elizabeth Barton travelled the country speaking to large groups of people. As her reputation grew people travelled to St Sepulchre's Nunnery to "consult her about their lives and sins, to ask her to discern spirits, or to seek her intercession for the sick, the dying, and the dead". Barton also told the people that God approved of pilgrimages and the practice of Mass. In other words, she claimed that God supported those things that were being attacked by religious reformers such as Martin Luther.

In October 1532 Henry VIII agreed to meet Elizabeth Barton again. According to the official record of this meeting: "She (Elizabeth Barton) had knowledge by revelation from God that God was highly displeased with our said Sovereign Lord (Henry VIII)... and in case he desisted not from his proceedings in the said divorce and separation but pursued the same and married again, that then within one month after such marriage he should no longer be king of this realm, and in the reputation of Almighty God should not be king one day nor one hour, and that he should die a villain's death."

Soon afterwards the King discovered that Anne Boleyn was pregnant. As it was important that the child should not be classed as illegitimate, arrangements were made for Henry and Anne to get married. King Charles V of Spain threatened to invade England if the marriage took place, but Henry ignored his threats and the marriage went ahead on 25th January, 1533. It was very important to Henry that his wife should give birth to a male child. Without a son to take over from him when he died, Henry feared that the Tudor family would lose control of England.

During this period Edward Bocking produced a book detailing Barton's revelations. In 1533 a copy of Bocking's manuscript was made by Thomas Laurence of Canterbury, and 700 copies of the book were issued by the printer John Skot, who supplied 500 copies to Bocking. Thomas Cromwell discovered what was happening and ordered that all copies were seized and destroyed. This operation was successful and no copies of the book exists today. (20)

In the summer of 1533 Archbishop Thomas Cranmer wrote to the prioress of St Sepulchre's Nunnery asking her to bring Elizabeth Barton to his manor at Otford. On 11th August she was questioned, but was released without charge. Thomas Cromwell then questioned her and, towards the end of September, Edward Bocking was arrested and his premises were searched. Bocking was accused of writing a book about Barton's predictions and having 500 copies published. Father Hugh Rich was also taken into custody. In early November, following a full scale investigation, Barton was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

Elizabeth Barton was examined by Thomas Cromwell, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Bishop Hugh Latimer. During this period she had one final vision "in which God willed her, by his heavenly messenger, that she should say that she never had revelation of God". In December 1533, Cranmer reported "she confessed all, and uttered the very truth, which is this: that she never had visions in all her life, but all that ever she said was feigned of her own imagination, only to satisfy the minds of them the which resorted unto her, and to obtain worldly praise."

Peter Ackroyd, the author of Tudors (2012) has suggested that Barton had been tortured: "It may be that she was put on the rack. In any case it was declared that she had confessed that all her visions and revelations had been impostures... It was then determined that the nun should be taken throughout the kingdom, and that she should in various places confess her fraudulence." (24) Barton secretly sent messages to her adherents that she had retracted only at the command of God, but when she was made to recant publicly, her supporters quickly began to lose faith in her.

Eustace Chapuys, reported to King Charles V on 12th November, 1533, on the trial of Elizabeth Barton: "The king has assembled the principal judges and many prelates and nobles, who have been employed three days, from morning to night, to consult on the crimes and superstitions of the nun and her adherents; and at the end of this long consultation, which the world imagines is for a more important matter, the chancellor, at a public audience, where were people from almost all the counties of this kingdom, made an oration how that all the people of this kingdom were greatly obliged to God, who by His divine goodness had brought to light the damnable abuses and great wickedness of the said nun and of her accomplices, whom for the most part he would not name, who had wickedly conspired against God and religion, and indirectly against the king."

A temporary platform and public seating was erected at St. Paul's Cross and on 23rd November, 1533, Elizabeth Barton made a full confession in front of a crowd of over 2,000 people. "I, Dame Elizabeth Barton, do confess that I, most miserable and wretched person, have been the original of all this mischief, and by my falsehood have grievously deceived all these persons here and many more, whereby I have most grievously offended Almighty God and my most noble sovereign, the King's Grace. Wherefore I humbly, and with heart most sorrowful, desire you to pray to Almighty God for my miserable sins and, ye that may do me good, to make supplication to my most noble sovereign for me for his gracious mercy and pardon."

Over the next few weeks Elizabeth Barton repeated the confession in all the major towns in England. It was reported that Henry VIII did this because he feared that Barton's visions had the potential to cause the public to rebel against his rule: "She... will be taken through all the towns in the kingdom to make a similar representation, in order to efface the general impression of the nun's sanctity, because this people is peculiarly credulous and is easily moved to insurrection by prophecies, and in its present disposition is glad to hear any to the king's disadvantage."

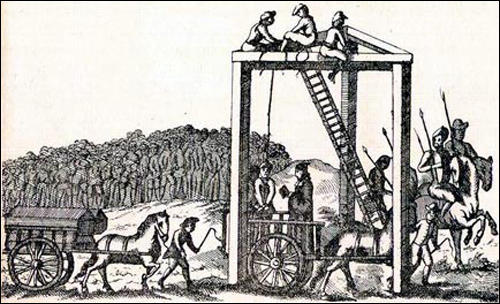

Parliament opened on 15th January 1534. A bill of attainder charging Elizabeth Barton, Edward Bocking, Henry Risby (warden of Greyfriars, Canterbury), Hugh Rich (warden of Richmond Priory), Henry Gold (parson of St Mary Aldermary) and two laymen, Edward Thwaites and Thomas Gold, with high treason, was introduced into the House of Lords on 21st February. It was passed and then passed by the House of Commons on 17th March. (29) They were all found guilty and sentenced to be executed on 20th April, 1534. They were "dragged through the streets from the Tower to Tyburn".

On the scaffold Elizabeth Barton told the assembled crowd: "I have not only been the cause of my own death, which most justly I have deserved, but also I am the cause of the death of all these persons which at this time here suffer. And yet, to say the truth, I am not so much to be blamed considering it was well known unto these learned men that I was a poor wench without learning - and therefore they might have easily perceived that the things that were done by me could not proceed in no such sort, but their capacities and learning could right well judge from whence they proceeded... But because the things which I feigned was profitable unto them, therefore they much praised me... and that it was the Holy Ghost and not I that did them. And then I, being puffed up with their praises, feel into a certain pride and foolish fantasy with myself."

John Husee witnessed their deaths: "This day the Nun of Kent, with two Friars Observants, two monks, and one secular priest, were drawn from the Tower to Tyburn, and there hanged and headed. God, if it be his pleasure, have mercy on their souls. Also this day the most part of this City are sworn to the King and his legitimate issue by the Queen's Grace now had and hereafter to come, and so shall all the realm over be sworn in like manner." The executions were clearly intended as a warning to those who opposed the king's policies and reforms. Elizabeth Barton's head was impaled on London Bridge, while the heads of her associates were placed on the gates of the city.

Sharon L. Jansen, the author of Dangerous Talk and Strange Behaviour: Women and Popular Resistance to the Reforms of Henry VIII (1996) has pointed out that historians have either "defended her as a saint or condemned her as a charlatan." Jack Scarisbrick argues that most historians have dismissed her as a "mere hysteric or fraud". However, "whatever else she may or may not have been, she was indisputably a powerful, courageous and dangerous woman whom the wracking anxiety of the late summer and autumn of 1533 required should be destroyed."

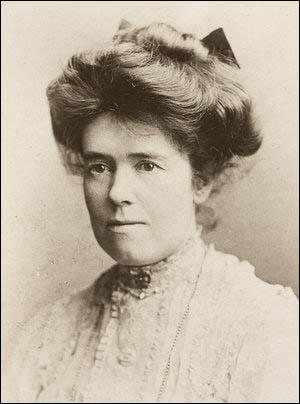

On this day in 1769 Amelia Opie, an opponent of slavery and supporter of parliamentary reform is born.

Amelia Alderson, the only child of James Alderson and his wife, Amelia Briggs Alderson, was born in Norwich on 12th November 1769. Her father was a physician and the son of a dissenting minister in Lowestoft.

As a child Amelia was high spirited and impetuous, traits which her mother, who was "as firm from principle, as she was gentle in disposition" tried to restrain. Her mother was "somewhat of a disciplinarian" and forced her daughter to overcome girlish fears of beetles and frogs by holding them in her hand.

Her mother also brought her up to care for those who came from less privileged backgrounds. After her death on 31st December 1784 she became her father's housekeeper and hostess. According to her biographer, Amelia "was vivacious, attractive, interested in fine clothes, educated in genteel accomplishments, and had several admirers".

Amelia spent her youth writing poetry and plays and organizing amateur theatricals. She took a keen interest in the arts and in 1790 she published anonymously, The Dangers of Coquetry. She was a regular visitor to London and became friends with William Godwin, Mary Wollstonecraft, Elizabeth Inchbald and Thomas Holcroft. During this period she was described by a friend as "universally loved and respected" for uniting "manly wisdom", "feminine gentleness", and "attractive manners".

Amelia and her father held strong political and religious views. They were religious dissenters and attended the Octagon Presbyterian Chapel, and associated with the Unitarians. They both supported parliamentary reform and the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, which excluded dissenters from public office. In September 1794 some Norwich reformers began a periodical of their own, The Cabinet, and Amelia contributed fifteen poems to the first three issues.

Three of her political friends, John Horne Tooke, Thomas Hardy and John Thelwall began to organise a convention to discuss parliamentary reform. When the authorities heard what was happening, Tooke and the other two men were arrested and committed to the Tower of London and charged with high treason. The trial began at the Old Bailey on 28th October, 1794. The prosecution argued that the men were guilty of treason as they organised meetings where people were encouraged to disobey King and Parliament. However, the prosecution was unable to provide any evidence that Tooke and his co-defendants had attempted to do this and the jury returned a verdict of "Not Guilty". It is claimed that if the men had been found guilty Amelia would have emigrated to the United States.

John Opie was a successful portrait artist who came from a working-class background. He was married to Mary, the daughter of Benjamin Bunn, a solicitor and moneylender. According to Mary Wollstonecraft the marriage was unhappy as "she was too much of a flirt to be a proper companion for him". They divorced in 1796 and he married Amelia on 8th May 1798.

Amelia Opie continued to write and her novel, The Father and Daughter was published in 1801. It told a story of how a daughter's seduction sent her father mad. It sold 9,500 copies in 35 years. This was followed by Adeline Mowbray: Mother and Daughter (1804). The novel concerns a women who lives to repent her rejection of marriage. Claire Tomalin has argued that both these novels were attacks on the lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin.

In 1805 John Opie became professor at the Royal Academy. His lectures were well regarded but unfortunately he died on 9th April 1807. His biographer, Robin Simon, claimed that "Opie's death, which followed the intense preparation of these lectures, and his customary incessant painting, has been partly at least attributed to overwork."

Opie continued to write poetry, short-stories and novels. This included Temper, or, Domestic Scenes: a Tale (1812), Tales of Real Life (1813), Valentine's Eve (1816), New Tales (1818), Tales of the Heart (1820) and Madeline: a Tale (1822). Her novels made Opie the most respected woman fiction writer after Maria Edgeworth.

Amelia Opie's beauty continued to attract the attentions of men. The young dramatist Edward Fitzball saw that "she was worshipped in society, not only for her great talent and her polished manners, but for her peculiar beauty... she was so voluptuous, yet so delicate and feminine, especially when she sang". Anna Eliza Bray commented that she had rarely encountered a woman "of such fascinating powers of conversation".

Amelia Opie developed a close relationship with Joseph Gurney, a minister for the Society of Friends. Under his influence she became active in the campaign against the slave-trade. On 8th April, 1825, Lucy Townsend, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd, Sarah Wedgwood and Sophia Sturge formed the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (later the group changed its name to the Female Society for Birmingham). The group "promoted the sugar boycott, targeting shops as well as shoppers, visiting thousands of homes and distributing pamphlets, calling meetings and drawing petitions."

The society which was, from its foundation, independent of both the national Anti-Slavery Society and of the local men's anti-slavery society. As Clare Midgley has pointed out: "It acted as the hub of a developing national network of female anti-slavery societies, rather than as a local auxiliary. It also had important international connections, and publicity on its activities in Benjamin Lundy's abolitionist periodical The Genius of Universal Emancipation influenced the formation of the first female anti-slavery societies in America".

The formation of other independent women's groups soon followed the setting up of the Female Society for Birmingham. Amelia Opie and Anna Gurney established a group in Norwich. Other groups were formed in Nottingham (Ann Taylor Gilbert), Sheffield (Mary Ann Rawson, Mary Roberts), Leicester (Elizabeth Heyrick, Susanna Watts), Glasgow (Jane Smeal), London (Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck, Mary Foster), Darlington (Elizabeth Pease) and Chelmsford (Anne Knight). By 1831 there were seventy-three of these women's organisations campaigning against slavery.

Amelia Opie was now a very committed Quaker. Mary Russell Mitford commented that Amelia "is all over Quakerized", though "just as kind and good-humoured as ever" and after "about a quarter of an hour's chat" able to forget "her thee's and thou's" and "altogether as merry as she used to be". Opie put her energies into the kind of philanthropic work promoted by Quakers. "She visited workhouses, hospitals, prisons, and the poor; promoted a refuge for reformed prostitutes."

The Slavery Abolition Act was passed on 28th August 1833. This act gave all slaves in the British Empire their freedom. The British government paid £20 million in compensation to the slave owners. The amount that the plantation owners received depended on the number of slaves that they had. For example, Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, received £12,700 for the 665 slaves he owned.

Amelia Opie attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention held at Exeter Hall in London, in June 1840 but as a woman was refused permission to speak. Anne Knight became aware that the artist, Benjamin Robert Haydon, had started a group portrait of those involved in the fight against slavery. She wrote a letter to Lucy Townsend complaining about the lack of women in the painting. "I am very anxious that the historical picture now in the hand of Haydon should not be performed without the chief lady of the history being there in justice to history and posterity the person who established (women's anti-slavery groups). You have as much right to be there as Thomas Clarkson himself, nay perhaps more, his achievement was in the slave trade; thine was slavery itself the pervading movement."

When the painting was completed it did not include Lucy Townsend or most of the leading female campaigners against slavery. Clare Midgley, the author of Women Against Slavery (1995) points out that as well as Anne Knight and Lucretia Mott, it does feature Amelia Opie, Elizabeth Pease, Mary Anne Rawson and Annabella Byron: "Haydon's group portrait is exceptional in that it does record the existence of women campaigners. Most other memorials did not. There are no public monuments to women activists to complement those to William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and other male leaders of the movement... In the written memoirs of these men, women tend to appear as helpful and inspirational wives, mothers and daughters rather than as activists in their own right."

Amelia continued to take an interest in literature and loved reading the work of Charles Dickens and Thomas Carlyle. In 1851 she went around the Great Exhibition in a wheelchair and, meeting Mary Berry in a similar vehicle, challenged her to a race. She wrote letters constantly, estimating in 1849 that she averaged six a day plus notes, and she maintained the custom of sending anonymous Valentines. She holidayed at Cromer and attended criminal trials at London and Norwich. (25)

Amelia Opie died after a short illness on 2nd December 1853.

On this day in 1815 Elizabeth Cady Stanton was born. She studied law under her father, who later became a New York Supreme Court judge. During this period she became a strong advocate of women's rights.

In 1840 Elizabeth married the lawyer, Henry Bewster Stanton. The couple both became active members of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Later that year, Stanton and Lucretia Mott, travelled to London as delegates to the World Anti-Slavery Convention. Both women were furious when they, like the British women at the convention, were refused permission to speak at the meeting. Stanton later recalled: "We resolved to hold a convention as soon as we returned home, and form a society to advocate the rights of women."

However, it was not until 1848 that Stanton and Lucretia Mott organised the Women's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls. Stanton's resolution that it was "the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves the sacred right to the elective franchise" was passed, and this became the focus of the group's campaign over the next few years.

In 1866 Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone established the American Equal Rights Association. The following year, the organisation became active in Kansas where Negro suffrage and woman suffrage were to be decided by popular vote. However, both ideas were rejected at the polls.

In 1868 Stanton and Susan B. Anthony established the political weekly, The Revolution, and the following year the two women formed a new organisation, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). The organisation condemned the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments as blatant injustices to women. The NWSA also advocated easier divorce and an end to discrimination in employment and pay.

Another group, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), was also active in the campaign for women's rights and by the 1880s it became clear that it was not a good idea to have two rival groups campaigning for votes for women. After several years of negotiations, the AWSA and the NWSA merged in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Stanton was elected as NAWSA first president but was replaced by Susan B. Anthony in 1892.

Stanton was also a historian of the struggle for women's rights and with Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage, complied and published the four volume, The History of Woman Suffrage (1881-1902).

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, whose autobiography, Eighty Years and More, was published in 1898, died in New York, on 26th October, 1902.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton is the fourth from the left in the bottom row.

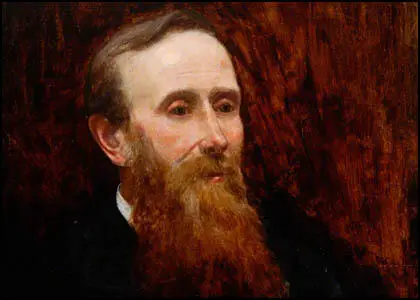

On this day in 1837 Thomas Burt was born in the colliery village of Murton Row. His father, Peter Burt, a miner, was an active trade unionist and a Primitive Methodist. After a bitter mining strike Burt was victimized and the family were forced to move from their tied cottage.

After two years of schooling, Thomas Burt, aged only ten, became a trapper boy in Haswell Colliery. Burt worked in a wide variety of pits, and like his father, was forced to move because of his union activities. In 1852 Burt was employed at Seaton Delaval Colliery where he stayed for thirteen years.

Despite his brief schooling, Burt had a strong love of reading. His favourite authors incuded Percy Busshe Shelley, Charles Dickens, Thomas Carlyle, John Stuart Mill and John Ruskin and in order to obtain books, Burt had to walk a distance of eighteen miles to Newcastle. Burt's knowledge of politics and economics impressed his fellow miners and in 1863 he was elected secretary and agent of the Northumberland Miners Association (NMA).

Following the 1867 Reform Act, the working class made up the majority of the electorate. It was now possible for working class candidates to win parliamentary elections. In 1874 General Election Burt stood as the Radical Labour candidate for Morpeth. The local Liberal Party agreed not to put up a candidate in Morpeth and Burt easily beat his Conservative opponent (3,332 to 585). Burt joined Alexander Macdonald, another miner who had been elected as the Lib-Lab MP for Stafford.

In the House of Commons Burt campaigned for reform of the 1871 Trade Union Act, land reforms suggested by Henry George, in his book, Our Land and Land Policy, the disestablishment of the Church of England, Irish Home Rule and adult male suffrage. Burt was also active in the Temperance Society and the International League of Peace.

Burt was re-elected unopposed in the 1880 General Election and held the seat for the next thirty-eight years. After the 1892 General Election, William Gladstone appointed Thomas Burt as Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade, a post he held for three years. Burt remained loyal to the Liberal Party and refused to join the Independent Labour Party when it was formed in 1893.

Ill-health forced Thomas Burt to retire at the 1918 General Election. He spent the final three years bed-ridden before his death on 12th April 1922.

On this day in 1865 Elizabeth Gaskell died. Elizabeth Stevenson married William Gaskell, a minister at their local Unitarian chapel on 30th August, 1832. The author of Gaskell: A Habit of Stories (1993) has argued: "They shared a faith and a love of literature and music but often seemed a contrast in appearance and temperament. While Elizabeth was of medium height, tending to plumpness (especially in later life), with an open smile, a constant flow of talk, and a distinct romantic streak, William was extremely tall and thin and apparently austere, with a dry sense of humour and an infinite capacity for hard work. Yet the marriage appears to have been extremely close, despite Elizabeth's many absences from home in later years."

In July 1833 Gaskell's first child, a daughter, was born dead. Her first surviving daughter, Marianne, was born on 12th September 1834 and her daughter's first years are recorded in Gaskell's diary: "She will talk before she walks I think. She can say pretty plainly papa, dark, stir, ship, lamp, book, tea, sweep." Another daughter, Margaret Emily, was born on 5th February 1837.

Gaskell's poem, Sketches among the Poor, appeared in The Blackwood Magazine in 1837. Her friends encouraged her to do more writing but she felt that she needed to concentrate on caring for her children. She later wrote: "When I had little children I do not think I could have written stories because I should have become too much absorbed in my fictitious people to attend to my real ones... everyone who tries to write stories must become absorbed in them (fictitious though they be) if they are to interest their readers."

Gaskell's next child was also born dead. She gave birth to Florence Elizabeth on 7th October 1842. The family now moved to a larger house at 121 Upper Rumford Street, Manchester. On 23rd October 1844 came the birth of the Gaskells' son William, but at ten months later he died of scarlet fever. After this Elizabeth sank into a deep depression which did not really end until her last daughter, Julia Bradford was born in 1846. During this period the Gaskells became friends with the social reformers, Samuel Bamford and James Martineau.

Gaskell was kept busy with the duties of being a minister's wife. She became a member of the District Provident Society, and helped distribute soup tickets, food, and clothing for the poor. Most of William Gaskell's parishioners were textile workers and Elizabeth was deeply shocked by the poverty she witnessed in Manchester. Elizabeth, like her husband, became involved in various charity work in the city. She now considered herself past having anymore children started writing a novel that attempted to illustrate the problems faced by people living in industrial towns and cities. Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life was published in 1848 by Chapman and Hall.

With its casts of working-class characters and its attempt to address key social issues such as urban poverty, Chartism and the emerging trade union movement, Gaskell's novel shocked Victorian society. The Manchester Guardian accused Gaskell of unfairly criticising the employers and The Edinburgh Review denounced her ignorance of economics. However, it was greatly admired by other writers such as Charles Dickens, William Thackeray, John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle. The social reformer, Charles Kingsley, argued in Fraser's Magazine (April 1849), that the novel should be read by the educated classes: "Do they want to know why poor men, kind and sympathising as women to each other, learn to hate law and order, Queen, Lords and Commons, country-party and corn law leagues, all alike - to hate the rich in short? then let them read Mary Barton."

Claire Tomalin has pointed out: "With no more education than any other nice girl born in 1810; with marriage at twenty-one, and seven pregnancies thereafter; with all the domestic and social duties of the wife of a Unitarian minister, and the care and upbringing of her children; not to mention a taste for travel - prison visiting and humanitarian work among the poor - a social life as exuberant as that of Dickens and a circle of friends as large - with all this, still, at the age of thirty-six she became an enormously successful and respected writer in a hugely competitive and brilliant field."

In February 1850, Charles Dickens decided to join forces with his publisher, Bradbury & Evans, and his friend, John Forster, to publish the journal, Household Words. Dickens became editor and William Wills, a journalist he worked with on the Daily News, became his assistant. Dickens planned to serialise his new novels in the journal. He also wanted to promote the work of like-minded writers. The first person he contacted was Elizabeth Gaskell. Dickens had been very impressed with her first novel, Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life (1848) and offered to take her future work. She sent him Lizzie Leigh , a story about a Manchester prostitute, which appeared in the first issue, on 30th March 1850. Dickens also published her stories The Well of Pen Morfa and The Heart of John Middleton .

In August 1850 Gaskell met Charlotte Brontë at the summer home of James Kay-Shuttleworth. The two women became friends and took a keen interest in her children. She later recalled that Gaskell was "a woman of whose conversation and company I should not soon tire. She seems to me kind, clever, animated and unaffected". Gaskell also got to know Florence Nightingale. She admired her sense of duty but found her manner difficult: "She has no friend - and wants none. She stands perfectly alone, half-way between God and His creatures".

Elizabeth Gaskell continued to publish stories in Household Words including Traits and Stories of the Huguenots , Morton Hall , My French Master , The Squire's Story , Company Manners , An Accursed Race , Half a Lifetime Ago , The Poor Clare , My Lady Ludlow , The Sin of a Father and The Manchester Marriage . She also produced a series of stories that were published between 13th December 1851 and 21st May 1853, that eventually became the novel, Cranford. Her biographer, Jenny Uglow has suggested that the Cranford stories "make the dangerous safe, touching the tenderest spots of memory and bringing the single, the odd and the wanderer into the circle of family and community."

During this period Gaskell visited Charles Dickens at his home: "We were shown into Mr. Dickens' study... where he writes all his books... There are books all around, up to the ceiling, and down to the ground... after dinner ... quantities of other people came in. We were by this time in the drawing-room, which is not nearly so pretty or so home-like as the study... We heard some beautiful music... I kept trying to learn people's faces off by heart, that I might remember them; but it was rather confusing there were so very many. There were some nice little Dickens' children in the room, who were so polite, and well-trained."

Gaskell also began work on a new novel. Ruth (1853) caused even more uproar than Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life. As the author of Gaskell: A Habit of Stories has explained: "Ruth tells the story of a fifteen-year-old seamstress who is seduced and has an illegitimate son. Taken in by a Unitarian minister, Mr Benson, she is passed off as a widow, making a new life until she is exposed and publicly denounced, before finally ‘redeeming’ herself as a nurse in a fever epidemic. A brave attack on current hypocrisy, the novel was attacked not only for the sexual theme but because of Benson's ‘lie’; a copy was even burnt by members of William Gaskell's own congregation." Elizabeth Barrett Browning was one of those who condemned the heroine's death as authorial cowardice. "I am grateful to you as a woman for having treated such a subject. Was it quite impossible but that your Ruth should die?"

Gaskell's next novel, North and South (1855), also appeared in Household Words (2nd September 1854 to 27 January 1855). The book deals with the relationship between Margaret Hale and John Thornton, who ran a textile mill. It has been suggested that Gaskell was attempting to provide a more sympathetic portrait of factory owners. It is probably significant that she had become friendly with social reformer, Robert Hyde Greg, who owned Quarry Bank Mill.

Peter Ackroyd, the author of Dickens (1990) has pointed out: "Mrs Gaskell's North and South, which was proving too long and too unwieldy for serial publication. Mrs Gaskell herself was also somewhat difficult, particularly in her inability or slowness to cut her text as Dickens desired; nothing irritated him more than unprofessional behaviour, especially in novelists whom he knew to be inferior to himself, and although he kept his own communications with Mrs Gaskell relatively courteous he was far from flattering about her to his deputy." Gaskell was also often late in delivering her manuscript. Dickens commented to William Henry Wills that if he was her husband, he would feel compelled to "beat her". Dickens eventually edited the serial and she regarded the abrupt ending of the serial version as "mutilated... like a pantomime figure with a great large head and a very small trunk".

On this day in 1874 Rachel Barrett, the daughter of Welsh-speaking parents, Rees Barrett, land and road surveyor and Anne Barrett, née Jones, was born on 12th November 1874 at 23 Union Street, Carmarthen. Educated at a private school in Stroud, she later won a scholarship to Aberystwyth College, gaining a BSc (London) in 1904. After graduating with an external degree in 1904 she became a science teacher in Penarth.

Barrett explains in her autobiography that she was a supporter of women's suffrage: "In 1905 I became a science mistress at Penarth County School and taught there two years, and it was during this time that I became interested in the new movement for womans suffrage. In 1906, like everybody else, I read in the newspapers of the campaign of the militants and felt for the first time that they were doing the right and only thing. I had always been a suffragist - since I first began to think of the position of women at all - but with no hope of ever seeing women win the vote."

In the Autumn of 1906 Barrett heard Nellie Martel address a audience in Cardiff. At the end of the meeting she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). The following year she helped Adela Pankhurst when she arrived in Cardiff as the WSPU organiser for Wales. " I helped her in her work, speaking at meetings, indoors and outdoors, and falling into great disfavour with my headmistress who considered all public work of that kind unsuitable for a woman teacher, more especially when her science mistress was reported in the local papers as drenched at an open-air meeting at the Cardiff docks."

In 1907 Barrett resigned from her teaching post and enrolled as a student at the London School of Economics. She also helped the WSPU in the by-election campaign at Bury St. Edmunds. Later that year Christabel Pankhurst asked her to become a full-time WSPU organiser. Although sorry to give up her studies she noted that "it was a definite call and I obeyed." In 1910 she was appointed WSPU organizer for Wales and moved to Newport, Monmouthshire.

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Rachel Barrett, Gladice Keevil, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Mary Gawthorpe, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond and Edith New.

In January 1910 she led a deputation to see the Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George. "When the truce to militancy was decided upon during the time of the Conciliation Bill I was sent to the constituency of the chief opponent, Mr Lloyd George. There I interviewed his supporters, organised meetings and finally led a deputation to him of women from the constituency. We were received in house in Criccieth where we spent 2 1/2 hours around his dining table arguing hotly. We left, I more convinced than before of his determined opposition to the WSPU and the insincerity of his support of the suffrage, and the other women (mostly liberal and not WSPU members) with their eyes very much opened."

The discussion with David Lloyd George convinced her of the insincerity of his support for the suffrage cause. She had also trust in the Liberal government headed by Herbert Asquith. Barrett was now considered to be one of the most important member of the WSPU and Annie Kenney described her as "an exceptionally clever and highly educated woman, she was a devoted worker and had tremendous admiration for Christabel Pankhurst."

In early 1912 Christabel Pankhurst decided to run WSPU operations in France in order to avoid arrest. Annie Kenney was put in charge of the WSPU in London. She appointed Rachel Barrett as her assistant. Every week Annie travelled to Paris to receive Christabel's latest orders. Fran Abrams has pointed out: "It was the start of a cloak-and-dagger existence that lasted for more than two years. Each Friday, heavily disguised, Annie would take the boat-train via La Havre. Sundays were devoted to work but on Saturdays the two would walk along the Seine or visit the Bois de Boulogne. Annie took instructions from Christabel on every little point - which organiser should be placed where, circular letters, fund-raising, lobbying MPs... During the week Annie worked all day at the union's Clement's Inn headquarters, then met militants at her flat at midnight to discuss illegal actions."

At a meeting in France, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

As a result of this expulsion, the WSPU lost control of Votes for Women. They now published their own newspaper, The Suffragette. Although Annie Kenney was the official editor, Rachel Barrett was given control over the publication of the newspaper. According to her autobiography she thought it was "An appalling task as I knew nothing whatever of journalism. However, after terrible struggles and some mistakes I was able to carry on to the satisfaction of the editor in Paris, whom I went over to see every now and then and to whom I often talked on the telephone when I could always hear the click of Scotland Yard listening in."

In 1912 Christabel Pankhurst decided to start an arson campaign. The historian, Fern Riddell, has pointed out: "From 1912 to 1914, Christabel Pankhurst orchestrated a nationwide bombing and arson campaign the likes of which Britain had never seen before and hasn't experienced since. Hundreds of attacks by either bombs or fire, carried out by women using codenames and aliases, destroyed timber yards, cotton mills, railway stations, MPs' homes, mansions, racecourses, sporting pavilions, churches, glasshouses, even Edinburgh's Royal Observatory. Chemical attacks on postmen, postboxes, golfing greens and even the prime minister - whenever a suffragette could get close enough - left victims with terrible burns and sorely irritated eyes and throats, and destroyed precious correspondence."

On 30th April 1913 the police raided the WSPU's office at Lincoln's Inn House. As a result of the documents found several people were arrested including (editor of the The Suffragette), Edwy Godwin Clayton, Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney, Harriet Kerr (office manager), Beatrice Sanders (financial secretary), Geraldine Lennox (sub-editor) and Agnes Lake (business manager).

When he was arrested Clayton said: "I think this is rather a high-handed action. I am an extreme sympathizer with the Suffragette causes. What evidence have you against me?" He confirmed he had written the letter but refused to comment on the contents. The letter read: "Dear Miss Kenney, I am sorry to say it will be several days yet before I can be ready with which you want. I have devoted all this evening and all of yesterday evening to the business without success. Evidently it is a difficult matter, but not impossible. I nearly succeeded once last night and then spoilt what I had done in trying to improve upon it. By next week I shall be able to manage the exact proportions, and I will let you have the results as soon as I can. Please burn this."

During the trial Matthias McDonnell Bodkin read extracts from a document headed "Votes for Women" and underneath "YHB". Bodkin claimed that YHB stood for Young Hot Bloods. The label was derived from a taunt thrown at Emmeline Pankhurst in one of the newspapers, which ran: "Mrs Pankhurst will, of course, be followed blindly by a number of the younger and more hot-blooded members of the union". As a result of them being single women one newspaper described the Young Hot Bloods as "a spinsters' secret sect".

Bodkin claimed that the police seized a great number of documents, that showed according to Bodkin that Clayton "put his knowledge and his brain at the Union's disposal for the purpose of carrying out crimes and of producing the reign of terror in London." Receipts for money he had been paid by the union were produced in court.

The most incriminating evidence was a letter sent by Edwy Godwin Clayton to Jessie Kenney in April 1913 that was found inside a book on the 1831 Bristol Reform Riots. Bodkin said: "We did not know until these documents were seized at their offices that they had an analytical chemist in their service – a man who, as we know, written a secret letter which the vain folly of Miss Kenney causes her to leave in her bedroom. the letter he tells her he had been experimenting, and was on the brink of success. Clayton ended his letter: "Burn this letter."

Bodkin provided other documents written by Clayton. One document in Clayton's writing was headed "Various Suggestions" and read "Scheme of simultaneously smashing a considerable number of street fire-alarms. This will cause tremendous confusion and excitement and should be as especially a good idea. It should be at once easier and less risky to execute than some other operations". Particulars as to timber yards and cotton mills also followed, as well as a plan for burning down the National Health Insurance Office.

In his summing up Justice Walter Phillimore, remarked that it was one of the saddest trials in his experience of nearly sixteen years as a Judge. "How in morals and how in good practical sense could such things, if they be true be justified? It was said that great causes had never been won without breaking the law. That might be true of some cases; it was very untrue of others. If every recorded act of anarchy, then, as history proceeded on its long course, the human race would reach a position of absolute savagery, and the only chance of salvation would be the obliteration of memory."

During the trial, Rachel Barrett said: "When we hear of a bomb being thrown we say 'Thank God for that'. If we have any qualms of conscience, it is not because of things that happen, but because of things that have been left undone." Barrett was described by one of the prosecuting barristers at the trial as "a pretty but misguided young woman".

After an absence of an hour the jury found all the prisoners guilty, with strong recommendations for leniency of sentence in the case of the three younger women, Rachel Barrett, Geraldine Lennox and Agnes Lake. The Judge said: "I agree with you, gentlemen of the jury, in the discrimination which you have made between the younger and elder men and women… which I propose to show in their sentences: As I have said, I assume you have been animated through out by the best motives. It is not merely that some of you have committed organized outrages, but I am more concerned with the incitement that has been given to young and irresponsible women, whose actions are not always balanced by their reason to do things which you are sure to regret."

Barrett was sentenced to six months in prison but Annie Kenney was sentenced to eighteen months and Edwy Godwin Clayton got twenty-one months. Barrett immediately began a hunger strike in Holloway Prison. After five days she was released under the Cat and Mouse Act. Barrett was re-arrested and this time went on a hunger and thirst strike. When she was released she escaped to Edinburgh. where she was looked after by Dr Flora Murray.

While working at The Suffragette Rachel Barrett met Ida Wylie, the Australian novelist, who was a contributor to the paper, and they are thought to have become lovers. Together they visited Christabel Pankhurst in Paris. On her return Barrett had surgery and lived under a pseudonym (Rachel Ashworth) to avoid re-arrest.

A number of significant figures in the WSPU left the organisation over the arson campaign. This included Elizabeth Robins, Jane Brailsford, Lillian Dove Willcox, Laura Ainsworth, Eveline Haverfield and Louisa Garrett Anderson. Leaders of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage such as Henry N. Brailsford, Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman, argued "that militancy had been taken to foolish extremes and was now damaging the cause".

Hertha Ayrton, Lilias Ashworth Hallett, Janie Allan and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson stopped providing much needed money for the organization. Colonel Linley Blathwayt and Emily Blathwayt also cut off funds to the WSPU. In June 1913 a house had been burned down close to Eagle House. Under pressure from her parents, Mary Blathwayt resigned from the WSPU.

In February 1914, Christabel Pankhurst expelled Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst from the WSPU for refusing to follow orders. Beatrice Harraden, a member of the WSPU since 1905, wrote a letter to Christabel calling on her to bring an end to the arson campaign and accusing her of alienating too many old colleagues by her dictatorial behaviour: "It must be that... your exile (in Paris) prevents you from being in real touch with facts as they are over here."

Henry Harben complained that her autocratic behaviour had destroyed the WSPU: "People are saying that from the leader of a great movement you are developing into the ringleader of a little rebel Rump." According to Martin Pugh "she had fallen into the error of all autocratic leaders; her power to manipulate personnel was so complete that it left her increasingly surrounded by sycophants who lacked real ability."

Rachel Barrett remained loyal to Christabel Pankhurst. The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided".

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!".

It would seem that Rachel Barrett did not agree with this policy and she left her role at The Suffragette in August 1914. Barrett and Ida Wylie traveled to America. They bought a car and roamed around the country, from New York to San Francisco. Both women were close friends of Radclyffe Hall and gave her support during the obscenity trial following the publication of her lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness (1928). Hall lost the case and all copies of the novel were destroyed.

Rachel Barrett and Edith How-Martyn established the Suffragette Club (later the Suffrage Fellowship) in 1926 in order "to perpetuate the memory of the pioneers and outstanding events connected with women's emancipation and especially with the militant suffrage campaign 1905-1914, and thus keep alive the suffragette spirit".

In 1934 Rachel Barrett moved to Lamb Cottage, Sible Hedingham. She died of a cerebral haemorrhage on 26th August 1953, at the age of seventy-eight at the Carylls Nursing Home in Rusper, West Sussex.

On this day in 1907 Christabel Pankhurst asked Mary Phillips to run the Women's Social and Political Union in Scotland. Mary Phillips, the daughter of a doctor, W. Fleming Phillips, was born in Glasgow in 1880. Her father held progressive political views and encouraged her to become involved in the women's suffrage movement. In 1904 she was employed as a paid organiser of the Glasgow and West of Scotland Association for Women's Suffrage.

Phillips was also a socialist and wrote a regular column in Forward, a "Scots Weekly journal of socialism, trade unionism, and democratic thought" in which she often commented on the subject of parliamentary reform. She gradually became convinced that "constitutional" agitation had failed.

Mary Phillips joined the WSPU and in June 1907 and established a branch in Glasgow. On 12th November, 1907, Christabel Pankhurst wrote to her and asked if she would be willing to help Helen Fraser run WSPU campaigns in Scotland. Fraser, was overworked as she was also employed at the Scottish Council for Women's Trades. Her first task was to run a WSPU campaign in East Fife.

In March 1908 Mary Phillips was arrested and sentenced to six-weeks in Holloway Prison after taking part in a WSPU demonstration outside the House of Commons. She was arrested again after taking part in the 30th June demonstration and this time she was sentenced to three months imprisonment. On her release she was greeted at the prison gates by Flora Drummond. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "On her release on 18th September she was greeted by a bevy of WSPU members, led by Flora Drummond, all of whom were attired in full Scottish regalia and accompanied by pipers. Mary Phillips and her parents were transported in a carriage pulled by the women from Holloway to the Queen's Hall."

After her release Phillips joined Annie Kenney, Elsie Howey, Gladice Keevil, Clara Codd and Mary Blathwayt in the WSPU West of England campaign. Blathwayt wrote in her diary: "This afternoon I helped Annie Kenney make her plans for a West of England campaign, I wrote out lists of towns and dates which are to be sent to Mrs. Pankhurst and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence." In November, 1908, Phillips was making speeches with Kenney and Blathwayt in Plymouth.

In January 1909 Phillips became WSPU organiser in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. That summer she was active in Cornwall and Devon. In July she was arrested with Vera Wentworth and Elsie Howey, after interrupting a public meeting being held by Lord Carrington in Exeter. All three women went on hunger-strike and were released. Emily Blathwayt recorded in her diary: "Elsie Howey, Vera Wentworth and Mary Phillips were arrested at Exeter and imprisoned for a week and it is said they are going through the hunger strike as the 14 have done. The crowds were with them outside Lord Carrington's meeting and all resisted police and two working men were arrested. The women would not pay the fine."

Mary Blathwayt recorded in her diary on 5th August that Mary Phillips was very ill and was "released when she took to fainting." Soon afterwards Emmeline Pankhurst wrote to Phillips saying: "my dear girl take care of yourself and do everything in your power to recover your health and strength."

In November 1909 Mary Phillips wrote to Christabel Pankhurst asking for permission to take part in more militant activity. Pankhurst replied: "Nothing would be more mistaken at the present time. On no account run the risk of it, as the work you have been doing recently would all go to pieces." Phillips obeyed these instructions and stayed out of trouble for the next three years.

Phillips visited Eagle House near Batheaston in July 1910 with Vera Wentworth. Their host, was Mary Blathwayt, a fellow member of the WSPU. Her father Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Picea Pungens Glauca, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house.

In April 1912 she had been congratulated on her success as the WSPU organiser in Plymouth and her salary had been increased from £2 10s to £2 15s a week. Mary Phillips was arrested in July 1912 during a demonstration in Chester. However, her fine was paid, without her consent, by a local sympathiser.

In July 1913 Mary Phillips was dismissed as a WSPU organiser. Christabel Pankhurst wrote that she had been dissatisfied with her work as a WSPU organiser: "I want to say that if we had thought you would have made a success of another district we should have asked you to take one. I did not wish to hurt you needlessly by saying what always has been felt at headquarters that you are not effective as a district organiser." Considering the previous positive comments it seems that there was another reason for her dismissal. According to Martin Pugh, the author of The Pankhursts (2001): "Like other organisers, Mary Phillips suffered from the members' reluctance to fund arson and other attacks on property." Emily Blathwayt had also recorded in her diary that Phillips had been having doubts about the militant strategy.

Mary Phillips now joined Sylvia Pankhurst, Keir Hardie, Julia Scurr, Mary Phillips, Millie Lansbury, Eveline Haverfield, Nellie Cressall and George Lansbury, in the establishment of the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party. Phillips had previously described herself as a member of the "extreme left". Phillips also became involved in the production of a weekly paper for working-class women called The Women's Dreadnought. As June Hannam has pointed out: "The ELF was successful in gaining support from working women and also from dock workers. The ELF organized suffrage demonstrations and its members carried out acts of militancy."

Phillips became a full-time organiser for the East London Federation of Suffragettes on a salary of £2 a week. She lived about the ELF shop in Poplar and worked closely with May Billinghurst. In 1915 she joined the United Suffragists, working until February 1916 as its organiser in Southwark. She was later employed by the New Constitutional Society for Women's Suffrage, the Women's International League and the Save the Children Fund.

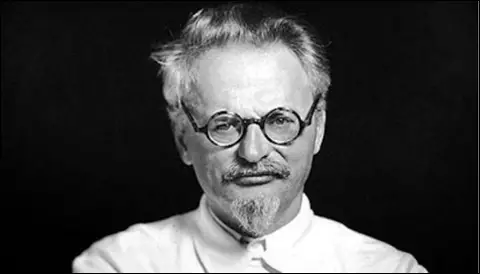

On this day in 1927 Joseph Stalin expels Leon Trotsky from the Soviet Communist Party. In the spring of 1927 Trotsky drew up a proposed programme signed by 83 oppositionists. He demanded a more revolutionary foreign policy as well as more rapid industrial growth. He also insisted that a comprehensive campaign of democratisation needed to be undertaken not only in the party but also in the soviets. Trotsky added that the Politburo was ruining everything Lenin had stood for and unless these measures were taken, the original goals of the October Revolution would not be achievable.

Stalin and Bukharin led the counter-attacks through the summer of 1927. At the plenum of the Central Committee in October, Stalin pointed out that Trotsky was originally a Menshevik: "In the period between 1904 and the February 1917 Revolution Trotsky spent the whole time twirling around in the company of the Mensheviks and conducting a campaign against the party of Lenin. Over that period Trotsky sustained a whole series of defeats at the hands of Lenin's party." Stalin added that previously he had rejected calls for the expulsion of people like Trotsky and Zinoviev from the Central Committee. "Perhaps, I overdid the kindness and made a mistake."

According to Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996): "The opposition then organized demonstrations in Moscow and Leningrad on November 7. These were the last two open demonstrations against the Stalinist regime. The GPU, of course, knew about them in advance but allowed them to take place. In Lenin's Party submitting Party differences to the judgment of the crowd was considered the greatest of crimes. The opposition had signed their own sentence. And Stalin, of course, a brilliant organizer of demonstrations himself, was well prepared. On the morning of November 7 a small crowd, most of them students, moved toward Red Square, carrying banners with opposition slogans: Let us direct our fire to the right - at the kulak and the NEP man, Long live the leaders of the World Revolution, Trotsky and Zinoviev.... The procession reached Okhotny Ryad, not far from the Kremlin. Here the criminal appeal to the non-Party masses was to be made, from the balcony of the former Paris hotel. Stalin let them get on with it. Smilga and Preobrazhensky, both members of Lenin's Central Committee, draped a streamer with the slogan Back to Lenin over the balcony."

Stalin argued that there was a danger that the party would split into two opposing factions. If this happened, western countries would take advantage of the situation and invade the Soviet Union. On 14th November 1927, the Central Committee decided to expel Leon Trotsky and Gregory Zinoviev from the party. This decision was ratified by the Fifteenth Party Congress in December. The Congress also announced the removal of another 75 oppositionists, including Lev Kamenev.

The Russian historian, Roy A. Medvedev, has explained in Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971): "The opposition's semi-legal and occasionally illegal activities were the main issue at the joint meeting of the Central Committee and Central Control Commission at the end of October, 1927... The Plenum decided that Trotsky and Zinoviev had broken their promise to cease factional activity. They were expelled from the Central Committee, and the forthcoming XVth Congress was directed to review the whole issue of factions and groups." Under pressure from the Central Committee, Kamenev and Zinoviev agreed to sign statements promising not to create conflict in the movement by making speeches attacking official policies. Trotsky refused to sign and was banished to the remote area of Kazhakstan.

On this day in 1969 investigative journalist Seymour Hersh breaks the story of the My Lai Massacre. For sometime stories had been circulating about deteriorating behaviour amongst US soldiers. Efforts were made by the US army to suppress information about the raping and killing of Vietnamese civilians but eventually, after considerable pressure from certain newspapers, it was decided to put Lieutenant William Calley on trial for war-crimes, In March, 1971, Calley was found guilty of murdering 109 Vietnamese civilians at My Lai. He was sentenced to life imprisonment but he only served three years before being released from prison.

During the war, twenty-five US soldiers were charged with war-crimes but William Calley was the only one found guilty Calley received considerable sympathy from the American public when he stated: "When my troops were getting massacred and mauled by an enemy I couldn't see, I couldn't feel, I couldn't touch... nobody in the military system ever described them anything other than Communists."

Critics of the war argued that as the US government totally disregarded the welfare of Vietnamese civilians when it ordered the use of weapons such as napalm and agent orange, it was hypocritical to charge individual soldiers with war-crimes. As the mother of one of the soldiers accused of killing civilians at My Lai asserted: "I sent them (the US army) a good boy, and they made him a murderer."

Philip Caputo, another US marine accused of killing innocent civilians, wrote later that it was the nature of the war that resulted in so many war-crimes being committed: "In a guerrilla war, the line between legitimate and illegitimate killing is blurred. The policies of free-fire zones, in which a soldier is permitted to shoot at any human target, armed or unarmed... further confuse the righting man's moral senses."

The publicity surrounding the My Lai massacre proved to be an important turning point in American public opinion. It illustrated the deterioration that was taking place in the behaviour of the US troops and undermined the moral argument about the need to save Vietnam from the "evils of communism". Vietnam was not only being destroyed in order to "save it" but it was becoming clear that those responsible for defeating communism were being severely damaged by their experiences.

mostly women and children dead on a road (16th March, 1968)