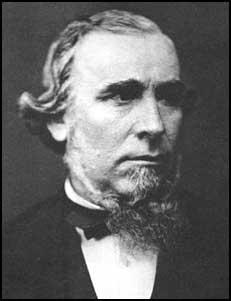

Alexander Macdonald

Alexander Macdonald, the son of a colliery worker, was born in New Monkland, Lanarkshire, on 21 June 1821. At the age of eight Alexander joined his father down the mines. Macdonald worked in both coal and ironstone mines for the next sixteen years.

As a boy Macdonald had received virtually no formal education, but in his twenties he began attending evening classes where he learnt Latin and Greek. He also took an interest in politics and carefully followed the career of Richard Oastler and his campaign against child labour.

Macdonald was one of the leaders of the 1842 Lanarkshire mining strike and after its defeat he lost his job. Macdonald found work in another colliery and was able to save enough money to attend winter sessions for students at Glasgow University. Every summer he returned to the pits until he had enough money for the next stage of his education.

Macdonald opened his own school in 1851 but after four years decided to concentrate his efforts in improving the pay and conditions of mine workers. In 1855 Macdonald formed the Coal and Iron Miners' Association and the following year the organisation fought a severe cut in wages. After a three month strike, the miners were starved back to work and had to accept the lower wages offered to them.

Undaunted by this failure, Macdonald continued to recruit members to his union. At a meeting in Leeds in November 1863, workers formed the Miners' National Association. Macdonald was elected president and over the next few years the organisation had many successes including the passing of the 1872 Mines Act.

In 1873 Alexander Macdonald was a member of the Royal Commission on Trade Unions and the following year he was invited to stand as the Lib-Lab candidate forStafford in the 1874 General Election. Macdonald won the seat and joined Thomas Burt as the first working-class members of the House of Commons.

In Parliament Macdonald tended to concentrate on trade union matters but he was also a strong supporter of Irish Home Rule. Macdonald's views became more moderate and some socialists, such as Karl Marx and Fredrich Engels, criticised him for his close relationship with Benjamin Disraeli and the Conservative Party.

Alexander Macdonald was re-elected for Stafford in the 1880 General Election but died the following year on 31st October 1881.

Primary Sources

(1) Alexander Macdonald, evidence before the Royal Commission on Trade Unions (28th April, 1868)

Lord Elcho: What year was it in which you entered the mines?

Alexander Macdonald: About the year 1835 I think; I could not fix the year. I entered the mines at about eight years of age. The condition of the miner's boy then was to be raised about 1 o'clock or 2 o'clock in the morning if the distance was very far to travel, and at that time I had to travel a considerable distance, more than three miles. We remained at the mine until 5 and 6 at night. It was an ironstone mine, very low, working about 18 inches, and in some instances not quite so high. Then I moved to coal mines. There we had low seams also, very low seams. There was no rails to draw upon, that is, tramways. We had leather belts for our shoulders. We had to keep dragging the coal with these ropes over our shoulders, sometimes round the middle with a chain between our legs. Then there was always another behind pushing with his head.

Lord Elcho: That work was done with children?

Alexander Macdonald: That work was done by boys, such as I was, from 10 to 11 down to eight, and I have known them as low as seven years old. In the mines at that time the state of ventilation was frightful.

Lord Elcho: Did that want of ventilation at that time lead to frequent accidents?

Alexander Macdonald: It did not lead to frequent accidents; but it lead to premature death.

Lord Elcho: Not to explosion?

Alexander Macdonald: No; carbonic acid gas in no case leads to explosions. There was no explosive gas in those mines I was in, or scarcely any. I may state incidentally here that in the first ironstone mine I was in there were some 20 or more boys besides myself, and I am not aware at this moment that there is one alive excepting myself.

(2) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

The Trades Unions were very dissatisfied with the attitude of the Liberal Government to the legal position of Trade Unionism. In 1869, at the instigation of John Stuart Mill, an organisation was formed under the name of the Labour Representation League to carry out a national campaign to secure the return of working men to Parliament. It does not appear to have been the intention of this League to form a party which could be permanently in opposition to the Liberal Party. Mills' idea was that, if the working classes put forward working-men candidates and threatened the Liberal majority, the Liberals would be glad to come to terms and provide opportunities for the return of working men. After the election of 1874 the League placed twelve working men in the field, and of these Thomas Burt and Alexander MacDonald were elected at Morpeth and Stafford respectively.

(3) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

In the 1874 General Election, twelve Labour candidates were offered to the electorate. When the bitter election campaigns were done, and the polling was over, England awoke to an amazing fact. Two Labour representatives had been returned to Parliament. Thomas Burt and Alexander MacDonald, the forlorn hope of the mighty army of British workers, flung open the gates of St. Stephen's; and those gates have never been quite shut against since.

(4) Alexander Macdonald, speech at union meeting (1873)

It was in 1856 that I crossed the border first to advocate a better Mines Act, true weighting, the education of the young, the restriction of the age to twelve years, the reduction of the working hours to eight in every twenty-four, the training of managers, the payment of wages weekly in the coin of the realm, no truck, and many other useful things too numerous to mention here.