On this day on 11th March

On this day in 1926 Ralph Abernathy was born in Lindon, Alabama. The son of a farmer, Abernathy was ordained as a Baptist minister in 1948.

Abernathy studied sociology at Atlanta University before becoming a pastor of the First Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. In Montgomery, like most towns in the Deep South, buses were segregated. On 1st December, 1955, Rosa Parks, a middle-aged tailor's assistant, who was tired after a hard day's work, refused to give up her seat to a white man.

After her arrest, Abernathy and his friend, Martin Luther King, organized protests against bus segregation. It was decided that black people in Montgomery would refuse to use the buses until passengers were completely integrated. King was arrested and his house was fire-bombed. Others involved in the Montgomery Bus Boycott also suffered from harassment and intimidation, but the protest continued.

For thirteen months the 17,000 black people in Montgomery walked to work or obtained lifts from the small car-owning black population of the city. Eventually, the loss of revenue and a decision by the Supreme Court forced the Montgomery Bus Company to accept integration. and the boycott came to an end on 20th December, 1956.

In 1957 Abernathy, Martin Luther King and Bayard Rustin, formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). King was president and Abernathy became the secretary-treasurer. The new organisation was committed to using nonviolence in the struggle for civil rights, and SCLC adopted the motto: "Not one hair of one head of one person should be harmed." Over the next few years Abernathy was arrested nineteen times.

Abernathy worked closely with Martin Luther King until his assassination in 1968. After King's death Abernathy became the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

He directed the Poor People's March in Washington (May, 1968), helped organize the Atlanta sanitation workers' strike (1968) and the Charleston hospital workers' strike (1969).

In 1977 Abernathy resigned from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and ran unsuccessfully for the Georgia congressional seat. His autobiography, And the Walls Came Tumbling Down, was published in 1989. Ralph David Abernathy died in Atlanta on 17th April, 1990.

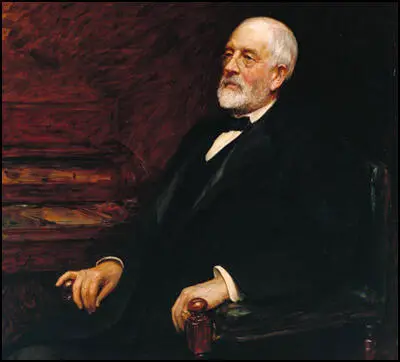

On this day in 1819 Henry Tate, the son of a clergyman was born in Chorley, Lancashire in 1819. When he was thirteen he moved to Liverpool and soon afterwards became an apprentice to a grocer. An ambitious young man, Tate owned his own shop by the time he was twenty. Over the next fifteen years he accumulated five more shops.

In 1859 Tate sold his shops and became a partner in a sugar refining company. Ten years later he obtained total control and changed the name of the company to Henry Tate & Sons. In 1872 Tate patented a new method of cutting sugar cubes. He built a new sugar refinery in Liverpool and over the next few years his business expanded very quickly.

Tate gave generously to charity. He founded the University Library at Liverpool and gave the nation the Tate Gallery, which was opened in 1897, and contained his own private collection of paintings. Henry Tate died on 5th December, 1899.

On this day in 1874 Charles Sumner, the son of a lawyer, was born in Boston, Massachusetts on 6th January, 1811. After graduating from Harvard University in 1833 he was admitted to the bar. Sumner developed radical political opinions and after reading An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans by Lydia Maria Child he became active in the campaign against slavery. Sumner also advocated education and prison reform.

Sumner joined the Whig Party but in 1848 helped to form the Free Soil Party. The following year he made a legal challenge against segregated schools in Boston. In 1851, with the support of the Democratic Party, Sumner was elected to Congress. He now became the Senate's leading opponent of slavery. After one speech Sumner made against pro-slavery groups in Kansas in 1856 he was beaten unconscious by Preston Brooks, a congressman from South Carolina. His injuries stopped him from attending the Senate for the next three years.

During the secession crisis in 1860-61, Sumner argued against any compromise deal and became one of the leaders of the Radical Republicans in Congress. On the outbreak of the American Civil War, he advocated the use of black troops to bring an end to slavery. As chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Sumner showed considerable political skill in preventing European intervention in the conflict.

Sumner clashed with Abraham Lincoln over his treatment of Major General John C. Fremont. On 30th August, 1861, Fremont, the commander of the Union Army in St. Louis, proclaimed that all slaves owned by Confederates in Missouri were free. Lincoln asked Fremont to modify his order and free only slaves owned by Missourians actively working for the South. When Fremont refused, he was sacked and replaced by the conservative General Henry Halleck. Sumner wrote to Lincoln complaining about his actions and remarked how sad it was "to have the power of a god and not use it godlike".

The situation was repeated in May, 1863, when General David Hunter began enlisting black soldiers in the occupied districts of South Carolina. Soon afterwards Hunter issued a statement that all slaves owned by Confederates in the area were free. Abraham Lincoln was furious and instructed him to disband the 1st South Carolina (African Descent) regiment and to retract his proclamation. Sumner supporting Hunter telling Lincoln that the Union could only be saved by freeing the slaves.

Charles Sumner also disagreed with Abraham Lincoln over suffrage. Sumner wanted all African Americans to have the vote whereas Lincoln favoured partial enfranchisement. Sumner thought that universal suffrage would help the government arguing that "the only Unionists of the South are black". Despite their many disagreements, the two men remained close friends. On one occasion Lincoln told Sumner "the only difference between you and me is a difference of a month or six weeks in time."

Despite their insistance that the white power structure in the South should be removed, most Radical Republicans argued that the deated forces should be treated leniently. Even while the American Civil War was going on Sumner argued that: "A humane and civilised people cannot suddenly become inhumane and uncivilized. We cannot be cruel, or barbarous, or savage, because the Rebels we now meet in warfare are cruel, barbarous and savage. We cannot imitate the detested example."

In 1866 Sumner and the Radical Republicans advocated the passing of the Civil Rights Bill, legislation that was designed to protect freed slaves from Southern Black Codes (laws that placed severe restrictions on freed slaves such as prohibiting their right to vote, forbidding them to sit on juries, limiting their right to testify against white men, carrying weapons in public places and working in certain occupations).

Sumner also opposed the policies of President Andrew Johnson and argued in Congress that Southern plantations should be taken from their owners and divided among the former slaves. They also attacked Johnson when he attempted to veto the extension of the Freeman's Bureau, the Civil Rights Bill and the Reconstruction Acts. However, the Radical Republicans were able to get the Reconstruction Acts passed in 1867 and 1868. Sumner also urged an extensive programme of economic aid, land distribution and free education for freed slaves.

In November, 1867, the Judiciary Committee voted 5-4 that Andrew Johnson be impeached for high crimes and misdemeanors. The majority report written by George H. Williams contained a series of charges including pardoning traitors, profiting from the illegal disposal of railroads in Tennessee, defying Congress, denying the right to reconstruct the South and attempts to prevent the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment.

On 30th March, 1868, Johnson's impeachment trial began. Sumner led the attack arguing that: "This is one of the last great battles with slavery. Driven from the legislative chambers, driven from the field of war, this monstrous power has found a refuge in the executive mansion, where, in utter disregard of the Constitution and laws, it seeks to exercise its ancient, far-reaching sway. All this is very plain. Nobody can question it. Andrew Johnson is the impersonation of the tyrannical slave power. In him it lives again. He is the lineal successor of John C. Calhoun and Jefferson Davis; and he gathers about him the same supporters."

Charles Sumner was bitterly disappointed when the Senate vote was one short of the required two-thirds majority for conviction. Sumner and other Radical Republicans were angry that not all the Republican Party voted for a conviction and Benjamin Butler claimed that Johnson had bribed two of the senators who switched their votes at the last moment.

President Ulysses S. Grant was also criticised by Sumner for not doing more for black civil rights. This upset senior members of the Republican Party and he was removed as chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee. Sumner lost all faith in Grant and in the 1872 presidential election he supported his rival, Horace Greeley. Charles Sumner died of a heart attack on 11th March, 1874.

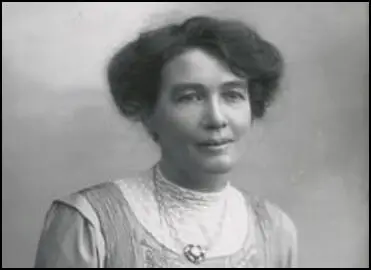

On this day in 1878 Kathleen Courtney, the youngest of five daughters of David Charles Courtney (1845–1909), was born in Gillingham on 11th March 1878. Her father was a senior officer of the Royal Engineers.

Courtney attended the Anglo-French College in Kensington and the Manse boarding-school in Malvern before spending seven months in Dresden studying German. In January 1897 she went to Lady Margaret Hall to read modern languages (French and German). While she was at the University of Oxford, she formed a lifelong friendship with Maude Royden.

The Courtney family were extremely wealthy and never had to worry about making a living and decided to devote her life to good causes. In 1908 she was appointed secretary of the North of England Society for Women's Suffrage. One of its members, Helena Swanwick, later revealed that Courtney arrived in Manchester "with a big reputation" as an outstanding organiser. In 1911 she moved to London where she worked closely with Millicent Fawcett as honorary secretary of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).

Herbert Asquith and his Liberal Party government still refused to support legislation. At its annual party conference in January 1912, the Labour Party passed a resolution committing itself to supporting women's suffrage. This was reflected in the fact that all Labour MPs voted for the measure at a debate in the House of Commons on 28th March. Soon afterwards Henry N. Brailsford and Kathleen Courtney, entered negotiations with the Labour Party as representatives of NUWSS.

In April 1912, the NUWSS announced that it intended to support Labour Party candidates in parliamentary by-elections. The NUWSS established an Election Fighting Fund (EFF) to support these Labour candidates. The EFF Committee, which administered the fund, included Kathleen Courtney, Margaret Ashton, Henry N. Brailsford, Muriel de la Warr, Millicent Fawcett, Catherine Marshall, Isabella Ford, Laurence Housman, Margory Lees and Ethel Annakin Snowden. The NUWSS also employed organizers such as Ada Nield Chew and Selina Cooper, who were active members of the Labour Party. Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999) has argued: "Her (Kathleen Courtney) arrival at the London headquarters coincided with the implementation of the federation scheme and her organizational skills were much appreciated."

In July 1914 the NUWSS argued that Asquith's government should do everything possible to avoid a European war. Two days after the British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914, Millicent Fawcett declared that it was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Although the NUWSS supported the war effort, it did not follow the WSPU strategy of becoming involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces.

Despite pressure from members of the NUWSS, Fawcett refused to argue against the First World War. Her biographer, Ray Strachey, argued: "She stood like a rock in their path, opposing herself with all the great weight of her personal popularity and prestige to their use of the machinery and name of the union." At a Council meeting of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies held in February 1915, Fawcett attacked the peace efforts of people like Mary Sheepshanks. Fawcett argued that until the German armies had been driven out of France and Belgium: "I believe it is akin to treason to talk of peace."

After a stormy executive meeting in Buxton all the officers of the NUWSS (except the Treasurer) and ten members of the National Executive resigned over the decision not to support the Women's Peace Congress at the Hague. This included Kathleen Courtney, Chrystal Macmillan, Margaret Ashton, Catherine Marshall, Eleanor Rathbone and Maude Royden, the editor of the The Common Cause.

Kathleen Courtney wrote when she resigned: "I feel strongly that the most important thing at the present moment is to work, if possible on international lines for the right sort of peace settlement after the war. If I could have done this through the National Union, I need hardly say how infinitely I would have preferred it and for the sake of doing so I would gladly have sacrificed a good deal. But the Council made it quite clear that they did not wish the union to work in that way."

According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "Mrs Fawcett afterwards felt particularly bitter towards Kathleen Courtney, whom she felt had been intentionally and personally wounding, and refused to effect any reconciliation, relying, as she said, on time to erase the memory of this difficult period."

In April 1915, Aletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited suffrage members all over the world to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Some of the women who attended included Kathleen Courtney, Mary Sheepshanks, Jane Addams, Alice Hamilton, Grace Abbott, Emily Bach, Lida Gustava Heymann, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, Chrystal Macmillan, Rosika Schwimmer. At the conference the women formed the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WIL). Courtney was elected as chairperson of the British section.

Courtney became a pacifist and during the First World War, Kathleen Courtney became associated with the Friends' War Victims Relief Committee. Her biographer, Janet E. Grenier, has pointed out: "She worked for the Serbian Relief Fund in Salonika, took charge of a temporary Serbian refugee colony in Bastia, Corsica, and was decorated by the Serbian government. Those who knew her during this period described her as full of life and fun and an exceptional administrator. She went on to work for the Friends' committee in France, Austria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Greece. She was in Vienna for three years where she was horrified by the post-war scenes of starvation, particularly among refugees."

Courtney continued to be involved in the campaign for women's suffrage. She helped establish the Adult Suffrage Society in 1916 and as joint-secretary she lobbied members of the House of Commons for extension of the franchise until the Qualification of Women Act was passed in 1918. The following year she became vice-president of the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship. As well as advocating the same voting rights as men, the organisation also campaigned for equal pay, fairer divorce laws and an end to the discrimination against women in the professions.

After the war she became a leading figure in the pacifist movement and was a member of the League of Nations Union and became a member of its executive in 1928. She spent much time in Geneva, working as first vice-president of the Peace and Disarmament Committee of Women's International Organizations. However, in 1933 she resigned from the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom because she believed that the league's pacifism, calling for complete disarmament, was unrealistic.

When Abyssinia was invaded by Italy in October 1935, she mobilized British and European women's organizations in the campaign to prevent civilian bombing. During the Second World War she worked for the Ministry of Information. In 1945 she attended the San Francisco conference that established the United Nations. Soon afterwards she became deputy chairman of the United Nations Association.

Kathleen Courtney died at her home, 3 Elm Tree Court on 7th December 1974. A memorial service was held on 11th April 1975 at St Martin-in-the-Fields.

On this day in 1916 Harold Wilson, the son of Herbert Wilson (1882–1971) and his wife, Ethel Seddon (1882–1957), was born in Milnsbridge on the outskirts of Huddersfield on 11th March 1916. His father was a chemist and his mother, a former school teacher.

Wilson was educated at New Street Elementary School (1920-1927), Royds Hall School (1927-1932) and Bebington Grammar School (1932-1934). One of his teachers, Edgar Whitwarm, later recalled: "To Harold it was effortless. There was never anyone to touch him... He was the sort of boy a teacher comes across only once or twice in a lifetime. He was more or less top in everything."

Wilson's father had been a supporter of the Liberal Party but after the First World War he changed his allegiance to the Labour Party: "Although never himself poor, the young Harold saw real poverty and the reliance on charity all around him... The family instilled in Harold an austere view of life. Each member was a 'self-contained, self-sufficient person, disinclined to display feelings'. Harold learned that anxieties and problems were best kept under personal control. He was to become an intensely loyal, warm man but a lonely figure with few friends to whom he could relate his feelings."

His biographer, Roy Jenkins, has pointed out: "Wilson was a remarkably successful pupil, both at Royds Hall and at Wirral grammar school.... He was always a pre-eminent examination passer. But he showed no wide intellectual curiosity. He was superb at the syllabus, but he ranged little outside it. He was much less inquisitive culturally than was his fairly near Yorkshire neighbour and very near contemporary Denis Healey. Nor was he rebellious or iconoclastic. The centre of his extra-curricular activity was the local branch of the Boy Scouts. He was not much attracted by or good at team games, but concentrated on the rather lonely sport of long-distance running."

In the summer of 1934, Harold Wilson met Gladys Mary Baldwin, while visiting the tennis club where she was a member. Mary was the daughter of the Revd Daniel Baldwin, a Congregational minister. She had left school at sixteen and was working as a typist at Lever Brothers in Port Sunlight. Wilson later claimed it was love at almost first sight. But Mary says she took much longer to make up her mind.

Later that year he won a history exhibition at Jesus College. At Oxford University he came under the influence of his socialist history tutor, G. D. H. Cole. Wilson later wrote in his memoirs: "I had long held G.D.H. Cole in high regard and found this closer contact with him most congenial. He was a good-looking man, of medium height with a good head of hair, and most attractive in speech and address, except for the manner of his lectures. I had attended a number of them, which he delivered at great speed, eyes down, without a single note. His special subjects were economic organization and history, and he concentrated on these. I was left to teach economic theory, not the area I preferred. I took to spending most Tuesday and Wednesday evenings with him, helping with copy for and proofs of his articles for the New Statesman and Nation. When the work was finished, he used to pour out for each of us a glass of Irish whisky, which he preferred to Scotch. On one of these occasions he was celebrating his fiftieth birthday. He announced that he had made a resolution, to foreswear all reading of books and concentrate on writing them. He was already publishing at least one a year in addition to his other writings. For the most part they were highly topical and dated rather quickly but some, particularly those on economic history, have survived."

With the encouragement of Cole he joined the Labour Party. "It was G.D.H. Cole as much as any man who finally pointed me in the direction of the Labour Party. His social and economic theories made it intellectually respectable. My attitudes had been clarifying for some time and the catalyst was the unemployment situation. I had seen it years before in the Colne Valley, with members of my class jobless when they left school. My own father was still enduring his second painful period out of work. My religious upbringing and practical studies of economics and unemployment in which I had been engaged at Oxford combined in one single thought: unemployment was not only a severe fault of government, but it was in some way evil, and an affront to the country it afflicted."

However, Wilson did not join the Oxford Labour Club because it was dominated by public school Marxists. In his memoirs Wilson recalled. "One meeting... was enough for me... What I felt I could not stomach was all those Marxist public school products rambling on about the exploited workers and the need for a socialist revolution.... I felt that the Oxford Labour Club wasn't for the likes of me... certainly I never had any common cause with the public school Marxist."

Harold Wilson was a very hard-working student and his first academic triumph was to win the Gladstone Memorial Prize for a long essay on "The state and the railways in Great Britain 1823–63". This essay reflected his keen interest in the British Railway System. Another subject that he took a keen interest in was the American Civil War. The following year he won the George Webb Medley Senior Scholarship, which gave him £300 a year. He got a clear-cut first, and it has been claimed that he achieved the highest marks in PPE of any undergraduate of the decade. One of his tutors thought that even within his chosen subjects he lacked originality. "What he was superb at was the quick assimilation of knowledge, combined with an ability to keep it ordered in his mind and to present it lucidly in a form welcome to his examiners."

In 1937 Wilson began working with William Beveridge on the theories of John Maynard Keynes. It has been claimed that the two men did not like each other and Beveridge and according to Lord Longford he regarded Wilson as "a useful machine, not as a person". Ben Pimlott, the author of Harold Wilson (1992) has argued that over the next few years, Beverage continued to rely on Wilson whenever he needed "efficient, streamlined assistance... Wilson, meanwhile, reaped the benefits of their cold alliance in Beveridge's munificent patronage."

Beverage wrote about the abilities of Wilson at the time: "One of the difficulties of economics in the past has been that anybody who did really well (Wilson) has been liable at once to start teaching, and pass on just what he has been taught of necessarily theoretical work in his undergraduate course. Wilson now with me is applying his economic training to the study of concrete problems, and I am anxious that he should be able to make a success of them, as I believe he will so that he might be a still better teacher and economist two years hence."

On the outbreak of the Second World War he joined the civil service, "briefly in a lowly position but rising rapidly". Wilson was head-hunted by members of the Cabinet Secretariat. He was part of the secretariat of an Anglo-French committee which enabled him to meet both Winston Churchill and Charles De Gaulle. According to his memoirs, Churchill was impressed by the "lucidity of his memoranda".

On 1st January 1940, Wilson married Mary Baldwin. At the time she expected him to return to university teaching. She later told Roy Hattersley: "I loved being the wife of a don and would have been happy to remain one all my life." They rented a flat in Richmond. Mary Wilson was also a poet, whose work and personality attracted the admiration of John Betjeman. Wilson often slept in his office and Mary told friends that she was feeling isolated and lonely. "Harold was not very perceptive about female needs and emotions; his articulate, level-headed and undemonstrative parents had done little to prepare him for the temperament and desires of a hypersensitive wife confused by her own changing moods. From the beginning he did not appear to involve Mary in his political life."

Harold Wilson continued to impress his bosses and in August 1941, he was put was director of economics and statistics at the Ministry of Fuel and Power. As his biographer has pointed out he became an important figure in the need to increase the production of coal during the war: "Coal... was an absolutely major ingredient and potential bottleneck in Britain's war effort, with its flow of production from over 1000 separate companies and nearly 2000 collieries, both haphazardly measured and unsatisfactory in result. There can be no doubt that, if Wilson did not increase the output, he vastly improved the statistics and gave ministers a much clearer picture of actual and likely future production." Michael Foot has claimed: "Wilson's work on coal statistics is regarded throughout the civil service as one of the most brilliant statistical achievements in civil service history."

Hugh Gaitskell reported to Hugh Dalton that Wilson was "extraordinarily able... he is only twenty-six, or thereabouts, and is one of the most brilliant younger people about... he has revolutionised the coal statistics. The great thing about him is that he understands what statistics are administratively important and interesting. We must on no account surrender him either to the Army or to any other department"

Harold Wilson was impressed with Winston Churchill. He later wrote: "His qualities were transcendent. First, there was the quality of indomitable courage. Never in the hour of greatest peril doubting ultimate victory, he could at once rebuke and inspire fainter hearts than his own. That inner certainty which enabled him to stand almost alone in seeing and warning of the danger, that certainty became an unshakeable rock when it was Britain and the Commonwealth who stood alone... Winston Churchill had through his power over words, but still more through his power over the hearts of men, that rare ability to call out from those who heard him the sense that they were a necessary part of something greater than themselves; the ability to make each one feel just that much greater than he had been."

Wilson continued to be interested in politics and he became a member of the executive committee of the Fabian Society. In 1944 he was selected as the Labour Party candidate for Ormskirk. One newspaper reported: "At 28, Mr Wilson is looked on by socialists as a coming President Board of Trade or Chancellor of the Exchequer." He now resigned his position at the Ministry of Fuel and Power to become a tutor at University College. The following year he published the book New Deal for Coal (1945). "It was a well-argued, non-doctrinaire statement of the case for nationalizing the mines. The case was presented almost entirely on the grounds of efficiency rather than of socialist fulfilment. He even suggested that the chairman of the future coal board might be paid up to £15,000 a year - then a very large salary - to ensure managerial quality. It was a good subject to have chosen, for the public ownership of the coal industry was at the centre of the Labour programme and the miners were a powerful influence within both the Labour conference and the Parliamentary Labour Party."

Harold Wilson was elected to the House of Commons in the 1945 General Election. Wilson was only 29 but the new prime minister, Clement Attlee appointed him as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Fuel and Power under George Tomlinson. The News Chronicle reported: "Outstanding among the really new men on the Labour benches I would put the brilliant young civil servant, Harold Wilson... He is regarded by the Whitehall high-ups as one of the discoveries of the war. Wilson it was who supplied the Minister of Fuel and Power with his facts and figures, and his statistical digest of the coal industry... was such a model of clear and concise statement that even the industrial correspondents could not find any future with it." Christopher Mayhew, also elected for the first time in 1945, later commented that having a conversation with Wilson a daunting experience: "I watched his bulging cranium with anxiety as he talked, expecting the teeming brain within to burst out at any moment."

"He (Wilson) had progressed in March of that year from his job as parliamentary secretary to the Ministry of Works to being secretary for overseas trade within the Board of Trade, under the presidency of Sir Stafford Cripps. Wilson was very much a Cripps man at this stage, and it was the patronage of that ascetic lawyer, whose political star in 1947–50 was rising as fast as his health was declining." Two years later, Wilson entered the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade. He therefore became the youngest minister since William Pitt.

and Barbara Castle of the Keep Left Group (1951)

On this day in 1916 Olive Schreiner explains the importance of the Union of Democratic Control. "Our Union of Democratic Control has two objects. The one is to draw together into an organised body those English men and women of whom, as in every other country engaged in this war, there are many hundreds of thousands, who have not desired war, and who are determined that when the peace comes it shall be a reality, and not a hotbed for the raising of future wars. We feel that the Governments have made the wars - the peoples themselves must make the peace! We are organizing ourselves, that, when the time comes, we may be able effectively to act. Our second aim is to educate ourselves and others to this end."

At the end of July, 1914, it became clear to the British government that the country was on the verge of war with Germany. Four senior members of the government, David Lloyd George (Chancellor of the Exchequer), Charles Trevelyan (Parliamentary Secretary of the Board of Education), John Burns (President of the Local Government Board) and John Morley (Secretary of State for India), were opposed to the country becoming involved in a European war. They informed the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, that they intended to resign over the issue. When war was declared on 4th August, three of the men, Trevelyan, Burns and Morley, resigned, but Asquith managed to persuade Lloyd George, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, to change his mind.

The day after war was declared, Trevelyan began contacting friends about a new political organisation he intended to form to oppose the war. This included two pacifist members of the Liberal Party, Norman Angell and E. D. Morel, and Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party. A meeting was held and after considering names such as the Peoples' Emancipation Committee and the Peoples' Freedom League, they selected the Union of Democratic Control.

The four men agreed that one of the main reasons for the conflict was the secret diplomacy of people like Britain's foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey. They decided that the Union of Democratic Control should have three main objectives: (i) that in future to prevent secret diplomacy there should be parliamentary control over foreign policy; (ii) there should be negotiations after the war with other democratic European countries in an attempt to form an organisation to help prevent future conflicts; (iii) that at the end of the war the peace terms should neither humiliate the defeated nation nor artificially rearrange frontiers as this might provide a cause for future wars.

The founders of the Union of Democratic Control produced a manifesto and invited people to support it. Over the next few weeks several leading figures joined the organisation. This included J. A. Hobson, Charles Buxton, Ottoline Morrell, Philip Morrell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Arnold Rowntree, Morgan Philips Price, George Cadbury, Helena Swanwick, Fred Jowett, Tom Johnston, Bertrand Russell, Philip Snowden, Ethel Snowden, David Kirkwood, William Anderson, Mary Sheepshanks, Isabella Ford, H. H. Brailsford, Ben Spoor, Eileen Power, Israel Zangwill, Margaret Llewelyn Davies, Konni Zilliacus, Margaret Sackville and Olive Schreiner.

On this day in 1938 Adolf Hitler forces the resignation of Kurt von Schuschnigg as Chancellor of Austria. In 1932 Engelbert Dollfuss, the Austrian chancellor, appointed Schuschnigg as his minister of justice. The following year he became minister of education.

When Dollfuss was assassinated in 1934, Schuschnigg became the Austria's new chancellor. He attempted to eliminate the threat to his government by Heimwehr, a national paramilitary defence force, by disbanding it on October, 1936

Schuschnigg capitulated to Hitler at Berchtesgaden in February, 1938. He attempted to gain control of the situation by arranging for a plebiscite to be held on 13th March, 1938. However, this move was undermined when the German Army invaded two days before the plebiscite was due to take place. Schuschnigg was imprisoned by the Nazi Government until he was liberated by American troops in 1945.

After the Second World War Schuschnigg was a professor of political science at St. Louis in the USA (1948-67) and wrote The Brutal Takeover (1971). Kurt von Schuschnigg died in Innsbruck, Austria on 18th November, 1977.

On this day in 1941 Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act. Winston Churchill became British prime-minister in May, 1940. At the time Britain was in a very difficult situation. In 1940 Germany had a population of 80 million with a workforce of 41 million. Britain had a population of 46 million with less than half Germany's workforce. Germany's total income at market prices was £7,260 million compared to Britain's £5,242 million. More ominously, the Germans had spent five times what Britain had spent on armaments - £1,710 million versus £358 million. Churchill was informed that Britain would soon run out of money to fight the war.

Churchill asked Franklin D. Roosevelt for help to beat Nazi Germany. At first Roosevelt said he was unable to help because public opinion in the United States was completely opposed to becoming involved in the war. However, British intelligence had some important agents within the White House. This included Ernest Cuneo, Robert Sherwood and David Niles. Cuneo later recalled: "Given the time, the situation, and the mood, it is not surprising however, that BSC also went beyond the legal, the ethical, and the proper. Throughout the neutral Americas, and especially in the U.S., it ran espionage agents, tampered with the mails, tapped telephone, smuggled propaganda into the country, disrupted public gatherings, covertly subsidized newspapers, radios, and organizations, perpetrated forgeries - even palming one off on the President of the United States - violated the aliens registration act, shanghaied sailors numerous times, and possibly murdered one or more persons in this country."

Eventually Roosevelt was persuaded to change his mind. On 17th December, 1940, Roosevelt made a speech to the American public: "In the present world situation of course there is absolutely no doubt in the mind of a very overwhelming number of Americans that the best immediate defence of the United States is the success of Great Britain in defending itself; and that, therefore, quite aside from our historic and current interest in the survival of democracy in the world as a whole, it is equally important, from a selfish point of view of American defence, that we should do everything to help the British Empire to defend itself... In other words, if you lend certain munitions and get the munitions back at the end of the war, if they are intact - haven't been hurt - you are all right; if they have been damaged or have deteriorated or have been lost completely, it seems to me you come out pretty well if you have them replaced by the fellow to whom you have lent them."

Roosevelt asked Claude Pepper, Walter Lippmann, Charles Edward Marsh and Benjamin Cohen to help draft a plan to send military aid to Britain. Isolationists like Burton Wheeler of Montana, Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan and Thomas Connally of Texas argued that this legislation would lead to American involvement in the Second World War. In early February 1941 a poll by the George H. Gallup organisation revealed that only 22 percent were unqualifiedly against the President's proposal. It has been argued by Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998), has argued that the Gallup organization had been infiltrated by the British Security Coordination (BSC).

Hadley Cantril, a member of the faculty of Princeton University Department of Psychology, had used a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to establish the Office of Public Opinion Research. A supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and intervention in the Second World War he was also an agent for the British Security Coordination and did work for the anti-isolationist group, Fight for Freedom. Cantril was of the opinion that Roosevelt needed "an improving body of public opinion to sustain him in each measure of assistance to Britain and the USSR." Cantril was also an advisor to George H. Gallup and worked closely with David Ogilvy, who was employed by Gallup and was also an agent for BSC.

Another BSC agent, Sanford Griffith, established a company Market Analysts Incorporated and was initially commissioned to carry out polls for the anti-isolationist Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies. Griffith's assistant, Francis Adams Henson, a long time activist against the Nazi Germany government, later recalled: "My job was to use the results of our polls, taken among their constituents, to convince on-the-fence Congressmen and Senators that they should favor more aid to Britain."

As Richard W. Steele has pointed out: "public opinion polls had become a political weapon that could be used to inform the views of the doubtful, weaken the commitment of opponents, and strengthen the conviction of supporters." William Stephenson later admitted: "Great care was taken beforehand to make certain the poll results would turn out as desired. The questions were to steer opinion toward the support of Britain and the war... Public Opinion was manipulated through what seemed an objective poll."

Michael Wheeler, the author of Lies, Damn Lies, and Statistics: The Manipulation of Public Opinion in America (2007) has pointed out how this could have been done: "Proving that a given poll is rigged is difficult because there are so many subtle ways to fake data... a clever pollster can just as easily favor one candidate or the other by making less conspicuous adjustments, such as allocating the undecided voters as suits his needs, throwing out certain interviews on the grounds that they were non-voters, or manipulating the sequence and context within which the questions are asked... Polls can even be rigged without the pollster knowing it.... Most major polling organizations keep their sampling lists under lock and key."

The main target of these polls concerned the political views of leading politicians opposed to Lend-Lease. This included Hamilton Fish. In February 1941, a poll of Fish's constituents said that 70 percent of them favored the passage of Lend-Lease. James H. Causey, president of the Foundation for the Advancement of Social Sciences, was highly suspicious of this poll and called for a congressional investigation.

It has been argued that both Arthur Vandenberg and Thomas Connally were targeted by British Security Coordination in order to persuade the Senate to pass the Lend-Lease proposal. Mary S. Lovell, the author of Cast No Shadow (1992) believes that the spy, Elizabeth Thorpe Pack (codename "Cynthia") who was working for the BSC, played an important role in this: "Cynthia's second mission for British Security Coordination was to try and convert the opinions of senators Connally and Vandenberg into, if not support, a less heated opposition to the Lend Lease bill which literally meant the difference between survival and defeat for the British. Other agents of both sexes were given similar missions with other politicians... with Vandenberg she was successful; with Senator Connally, chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, she was not."

George Norris was a strong supporter of the Lend-Lease bill. He later recalled: "In the Senate the Lend-Lease bill produced one of the bitterest struggles of a bitter period. I never could understand from the arguments developed in the debate why any member of the Senate objected to the passage of the act. In all of the discussion, it seemed to me, the opposition to Lend-Lease closed its eyes and refused to recognize the circumstances responsible for the proposal. Hitler's triumphs had simplified America's choice. Either this country could accept him and try to get along with him, or it had to stem the march of his armies in his plan of world conquest. I place no faith in his protestation of a peaceful attitude toward the countries of the western hemisphere. His every deed and utterance established that once he had made himself supreme in Europe, Africa, and Asia the next step would be conquest of the Americas."

Burton Wheeler gave the most passionate speech against the proposed legislation: "Never before have the American people been asked or compelled to give so bounteously and so completely of their tax dollars to any foreign nation. Never before has the Congress of the United States been asked by any President to violate international law. Never before has this nation resorted to duplicity in the conduct of its foreign affairs. Never before has the United States given to one man the power to strip this nation of its defenses. Never before has a Congress coldly and flatly been asked to abdicate. If the American people want a dictatorship - if they want a totalitarian form of government and if they want war - this bill should be steam-rollered through Congress, as is the wont of President Roosevelt. Approval of this legislation means war, open and complete warfare. I, therefore, ask the American people before they supinely accept it: Was the last World War worthwhile?"

The major surprise of the debate was that Arthur Vandenberg announced on the floor of the Senate that he had finally decided to support the loan. He warned his colleagues: "If we do not lead some other great and powerful nation will capitalize our failure and we shall pay the price of our default." Richard N. Gardner, the author of Sterling Dollar Diplomacy in Current Perspective (1980), has argued that Vandenberg's speech was the "turning point in the Senate Debate" with sixteen other Republicans voting in favour of the bill.

On 11th March 1941, Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act. The legislation gave President Franklin D. Roosevelt the powers to sell, transfer, exchange, lend equipment to any country to help it defend itself against the Axis powers. A sum of $50 billion was appropriated by Congress for Lend-Lease. The money went to 38 different countries with Britain receiving over $31 billion.

When David Ogilvy read an early draft of The Quiet Canadian (1962) he requested that William Stephenson put pressure on H. Montgomery Hyde to remove all references to Hadley Cantril and George H. Gallup: "I beg you to remove all references to Hadley Cantril and Dr. Gallup... Dr. Gallup was and still is, a great friend of England. What you have written would cause him anguish - and damage. One does not want to damage one's friends... In subsequently years Hadley Cantril has done a vast amount of secret polling for the United States Government. What you have written would compromise him - and SIS (MI6) does not make a practice of compromising its friends."

On this day in 1954 women's suffrage campaigner Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence died.

Emmeline Pethick, the daughter of Henry Pethick, a businessman in Bristol, was born in Clifton on 21st October 1867. She later recalled: "My mother bore thirteen children, of whom five died in infancy. My youngest brother was born seventeen years after me. Those were the days of large families. I never heard my mother make any complaint about this excessive childbearing. She accepted it with complete surrender and even with satisfaction."

Henry Pethick was a devout Methodist. "As children we were all taken to Church as soon as we could walk and we had to sit very still indeed, because if not, we would be slapped afterwards. When we were older we had to remember and repeat the text at dinner-time, and if we failed to do this we were set to learn pieces of Scripture by heart."

Emmeline was sent away to boarding school in Devizes at the age of eight. A rebellious child, she was constantly in trouble with her teachers. After being transferred to a Quaker school she was accused of being "a corrupting influence on other children". Her biographer, Brian Harrison has argued: "Her lifelong instinctive sympathy with children was striking... She portrayed herself later as a truthful and rational child, but to adults she must have seemed wilful and stubborn."

In 1891 Emmeline became a voluntary social worker at the West London Methodist Mission. Emmeline helped organise a club for young working-class girls. Emmeline was shocked by the poverty she encountered and it was during this time she was converted to socialism. Emmeline believed it was important to give these girls a practical example of socialism in action. In 1895 Emmeline joined with Mary Neal to form the Esperance Club that was influenced by the ideas of William Morris, Edward Carpenter, and Walt Whitman. This involved helping a group of young women establish a co-operative dressmaking business.

In 1899 Emmeline met the wealthy lawyer, Frederick Lawrence. The couple fell in love but Emmeline refused to marry Frederick because he did not share her socialist beliefs. In 1900 she developed a hostel at Littlehampton for working girls' holidays. It was not until 1901, when Frederick had been converted to socialism, that Emmeline agreed to marry him. Frederick agreed to adopt Pethick-Lawrence as their joint name. Brian Harrison has pointed out: "It was the start of an unusual lifelong partnership in which each annexed the surname of the other, while each retained separate bank accounts and considerable autonomy within a marriage whose harmony was much advertised and celebrated."

Soon after her marriage Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence thought she was pregnant. Frederick wrote that the birth "will make us both extra happy". He added: "Isn't it splendid dear. My heart just singing and singing and won't keep quiet." However, Emmeline suffered a miscarriage and received news that she could not have children. Frederick wrote to her: "I am to you a splendid husband and you to me a splendid wife and it is enough!"

In 1901 Frederick Pethick-Lawrence became the owner of The Echo, a left-wing evening newspaper. He recruited friends from the socialist movement such as Ramsay MacDonald and H. N. Brailsford to write for the newspaper. Frederick also published and edited the monthly, Labour Record and Review (1905-07). Emmeline later argued: "His outstanding qualities of intellect, balanced judgment and practical administration in business and finance became the rock upon which I have built, since then, the structure of my life."

For the next four years Emmeline spent her time helping the Independent Labour Party and developing her ideas with the Esperance Club. However, when Emmeline read about the arrest and imprisonment of Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney in October 1905, she decided to take an interest in the suffrage movement. The following year she met Kenney and after a long discussion with her she decided to join the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

A few months after joining the WSPU Emmeline was arrested while trying to make a speech in the lobby of the House of Commons. Emmeline was sent to prison, the first of six terms of imprisonment that she served for her political activities. She later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "When the morning newspaper brought the unexpected news of my first arrest in the Suffrage Movement, my father reacted to it in precisely the same way as I should have reacted had our positions been reversed. He was proud that a child of his hand not hesitated to make a stand for the extension of democratic liberty."

Frederick Pethick-Lawrence also became involved in the struggle for the franchise. In 1907 Frederick and Emmeline started the journal Votes for Women. The Pethick-Lawrence's large home in London also became the office of the WSPU. It was also used as a kind of hospital where women made ill by their prison experiences could recover their strength before embarking on further militant acts. The couple also contributed more than £6000 to the funds of WSPU.

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Gladice Keevil, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Mary Gawthorpe, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond and Edith New.

In 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence had disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored her objections. As soon as this wholesale smashing of shop windows began, the government ordered the arrest of the leaders of the WSPU. Christabel escaped to France but Frederick and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. They were also successfully sued for the cost of the damage caused by the WSPU.

Both Emmeline and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence went on hunger strike and had to face the full rigours of forcible feeding twice a day for several days. He later recalled the experience in his memoirs, Fate Has Been Kind (1943): "The head doctor, a most sensitive man, was visibly distressed by what he had to do. It certainly was an unpleasant and painful process and a sufficient number of warders had to be called in to prevent my moving while a rubber tube was pushed up my nostril and down into my throat and liquid was poured through it into my stomach. Twice a day thereafter one of the doctors fed me in this way. I was not allowed to leave my cell in the hospital and for the most part I had to stay in bed. There was nothing to do but to read; and the days were very long and went very slowly."

Christabel Pankhurst later recorded: "Mother and Mr. and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence went on hunger-strike. The Government retaliated by forcible feeding. This was actually carried out in the case of Mr. and Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence. The doctors and wardresses came to Mother's cell armed with forcible-feeding apparatus. Forewarned by the cries of Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence… Mother received them with all her majestic indignation. They fell back and left her. Neither then nor at any time in her log and dreadful conflict with the government was she forcibly fed."

After Emmeline and Frederick were released from prison they began to speak openly about the possibility that this window-smashing campaign would lose support for the WSPU. At a meeting in France, in October 1912, Christabel Pankhurst told Emmeline and Frederick about the proposed arson campaign. When Emmeline and Frederick objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003) wrote: "Even the split with the WSPU did not end of this agony - the Pethick-Lawrences were still facing bankruptcy proceedings. An auction of their belongings was held at The Mascot, but raised only £300 towards their £1,100 court costs even though many friends arrived to buy personal possessions and give them back to the couple. Even the auctioneer returned to them a trinket he had bought as a keepsake. The rest of the costs were later taken from Fred's estate, plus a further £5,000 for repairs to shop windows damaged in the raids. Fortunately he had deep pockets and did not have to sell his home."

Pethick-Lawrence continued to work for the suffrage cause and spent most of her energies after 1912 writing for her journal, Votes for Women. She also joined the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Other members included Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard.

During the First World War Emmeline was a prominent member of the Women's International League for Peace. After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918 Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence stood as Labour candidate for Rusholme. As Brian Harrison pointed out: "she championing nationalization, a capital levy, equal pay, and an equal moral standard, but she came bottom of the poll with only a sixth of the votes cast."

In the 1920s and 1930s Emmeline worked for the Women's International League, an organisation committed to world peace. Emmeline also became involved in the campaign led by Marie Stopes to provide birth-control information to working class women. From 1926 to 1935 was president of the Women's Freedom League.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence published her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World, in 1938. The book is dedicated to her husband, "my unchanging comrade and my best friend". One critic argued: "Though impressively fair-minded and at times perceptive, her account of the suffragettes is essentially an uncritical and largely impersonal chronology. Nowhere did she convincingly justify the contradiction between her humanitarian and democratic instincts on the one hand, and her promotion of violent tactics and authoritarian suffrage structures on the other."

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence remained active in politics until 1950 when she had a serious accident that left her immobilized. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence looked after Emmeline until she died of a heart attack at her home at Gomshall, Surrey, on 11th March 1954. He wrote to a friend: "I feel a bit dazed. It is as though I was at a violin concerto with the violinist absent."

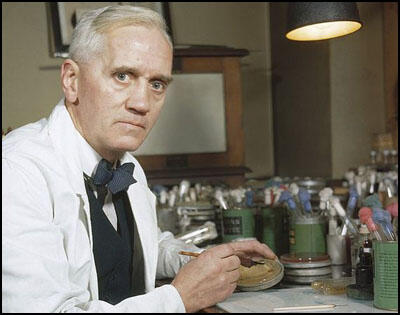

On this day in 1955 Alexander Fleming died from heart failure. Alexander Fleming was born at Lochfield Farm in Darvel on 6th August 1881. At the age of 12 he attended Kilmarnock Academy. When his father died, his oldest brother Hugh took over the running of the farm.

After leaving school Fleming found work with a shipping company in London. In 1899 the Boer War broke out and in an attempt to escape from a job he hated he joined the London Scottish. Although a good soldier he was indifferent to promotion and was content to remain a private.

In 1901 Fleming was left a legacy by his uncle and he decided to use the money to buy himself out of the army and to study medicine. As he had no formal qualifications, Fleming had to pass an examination before he was allowed to enter medical school. According to one of his biographers: "He had a few lessons, and then applied his prodigious memory and high intelligence to the task, passing top of all the candidates in the UK." He decided to study at St. Mary's Hospital in Paddington.

An outstanding doctor, Fleming was invited to join Almroth Wright at his laboratory at the Inoculation Department. Wright and his colleagues were responsible for developing an anti-typhoid vaccine. Fleming's first success was to take a compound, salvarsan (606), that treated syphilis in rabbits, and develop it so that it could be used on human beings.

On the outbreak of the First World War Fleming joined the Royal Army Medical Corps. Fleming and Almroth Wright were based in Boulogne. Fleming soon discovered that many of the wounded men being transported back from the Western Front were suffering from septicaemia, tetanus and gangrene. He was aware that white blood corpuscles, left to themselves, killed an enormous number of microbes. Yet the infections from war wounds were terrible. Fleming realised that part of the answer was that there was a great deal of dead tissue around the wound, providing a good culture in which microbes could flourish. In September 1915, he published an article in The Lancet advising surgeons to remove as much dead tissue as possible from the area of wounds.

Fleming research showed that the traditional treatment of infected wounds with antiseptics, was totally ineffective when used in the Casualty Clearing Station. He discovered that antiseptics did nothing to prevent gangrene in seriously injured soldiers. The reason for this was that scraps of underclothing and other dirty objects were driven by the force of an explosion deeply into the patient's tissues, where antiseptics were unable to reach.

Fleming and Almroth Wright realised that supporting the natural resources of the body would be more effective in the treatment of gangrene and the showed that a high concentration of saline solution would achieve this. However, they had great deal of difficulty in persuading the Royal Army Medical Corps to adopt this treatment.

One Canadian doctor who visited Boulogne was very impressed with Fleming: "Boulogne being the great supply port of the BEF, there was always a crowd of guests, and the talk grew animated. Though Fleming said little, he did a great deal to keep the conversation at a practical level with his felicitous and opportune remarks and his breadth of outlook. Another doctor who worked with Fleming remarked that "he never said more than he had to, but carried on calmly and efficiently with his work".

Fleming remained convinced that he would eventually find a successful treatment for infected wounds. "Surrounded by all these infected wounds, by men who were suffering and dying without our being able to do anything to help them, I was consumed by a desire to discover, after all this struggling and waiting, something which would kill those microbes."

After the war Fleming returned to St. Mary's Hospital in Paddington and in 1921 Fleming was made assistant director of the Inoculation Department. The following year he discovered lysozyme, a natural antibacterial enzyme which he found initially in human tears.

In 1928 Alexander Fleming was appointed as Professor of Bacteriology at the University of London. Later that year he was clearing out some old dishes in which he grew his cultures. On one of the mouldy dishes, he noticed that around the mould, the microbes had apparently been dissolved. He took a small sample of the mould and set it aside. He later identified it as of the penicillium family. He therefore named the anti-bacterial agent he had discovered penicillin.

Fleming published his findings in 1929 but it was not until during the Second World War that Howard Florey and Ernst Chain managed to isolate and concentrate penicillin. It was not until the end of the war that the antibiotic could be mass produced and was widely used. Fleming, Florey and Chain won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1945.

In October 1953 Fleming developed pneumonia. He was given an injection of penicillin. Fleming made a quick recovery and he later commented: "I had no idea it was so good." It was recently estimated that over 200 million lives have been saved by penicillin since 1945.

On this day in 1965 civil rights activist James Reeb died of his injuries. James Reeb was born in Wichita, Kansas, on 1st January, 1927. A Unitarian minister, Reeb was active in the civil rights movement.

After the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson during the voter registration drive by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) it was decided to dramatize the need for a federal registration law.

With the help of Martin Luther King and Ralph David Abernathy of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), leaders of the SCCC organised a protest march from Selma to the state capitol building in Montgomery, Alabama. The first march on 1st February, 1965, led to the arrest of 770 people. A second march, led by John Lewis and Hosea Williams, on 7th March, was attacked by mounted police. The sight of state troopers using nightsticks and tear gas was filmed by television cameras and the event became known as Bloody Sunday.

While in Selma on 8th March, Reeb was attacked by white mob with clubs. Reeb, who suffered massive head injuries, died in hospital on 11th March. His death resulted in a national outcry against the activities of white racists in the Deep South. 1945.