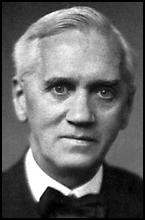

Alexander Fleming

Alexander Fleming was born at Lochfield Farm in Darvel on 6th August 1881. At the age of 12 he attended Kilmarnock Academy. When his father died, his oldest brother Hugh took over the running of the farm.

After leaving school Fleming found work with a shipping company in London. In 1899 the Boer War broke out and in an attempt to escape from a job he hated he joined the London Scottish. Although a good soldier he was indifferent to promotion and was content to remain a private.

In 1901 Fleming was left a legacy by his uncle and he decided to use the money to buy himself out of the army and to study medicine. As he had no formal qualifications, Fleming had to pass an examination before he was allowed to enter medical school. According to one of his biographers: "He had a few lessons, and then applied his prodigious memory and high intelligence to the task, passing top of all the candidates in the UK." He decided to study at St. Mary's Hospital in Paddington.

An outstanding doctor, Fleming was invited to join Almroth Wright at his laboratory at the Inoculation Department. Wright and his colleagues were responsible for developing an anti-typhoid vaccine. Fleming's first success was to take a compound, salvarsan (606), that treated syphilis in rabbits, and develop it so that it could be used on human beings.

On the outbreak of the First World War Fleming joined the Royal Army Medical Corps. Fleming and Almroth Wright were based in Boulogne. Fleming soon discovered that many of the wounded men being transported back from the Western Front were suffering from septicaemia, tetanus and gangrene. He was aware that white blood corpuscles, left to themselves, killed an enormous number of microbes. Yet the infections from war wounds were terrible. Fleming realised that part of the answer was that there was a great deal of dead tissue around the wound, providing a good culture in which microbes could flourish. In September 1915, he published an article in The Lancet advising surgeons to remove as much dead tissue as possible from the area of wounds.

Fleming research showed that the traditional treatment of infected wounds with antiseptics, was totally ineffective when used in the Casualty Clearing Station. He discovered that antiseptics did nothing to prevent gangrene in seriously injured soldiers. The reason for this was that scraps of underclothing and other dirty objects were driven by the force of an explosion deeply into the patient's tissues, where antiseptics were unable to reach.

Fleming and Almroth Wright realised that supporting the natural resources of the body would be more effective in the treatment of gangrene and the showed that a high concentration of saline solution would achieve this. However, they had great deal of difficulty in persuading the Royal Army Medical Corps to adopt this treatment.

One Canadian doctor who visited Boulogne was very impressed with Fleming: "Boulogne being the great supply port of the BEF, there was always a crowd of guests, and the talk grew animated. Though Fleming said little, he did a great deal to keep the conversation at a practical level with his felicitous and opportune remarks and his breadth of outlook. Another doctor who worked with Fleming remarked that "he never said more than he had to, but carried on calmly and efficiently with his work".

Fleming remained convinced that he would eventually find a successful treatment for infected wounds. "Surrounded by all these infected wounds, by men who were suffering and dying without our being able to do anything to help them, I was consumed by a desire to discover, after all this struggling and waiting, something which would kill those microbes."

After the war Fleming returned to St. Mary's Hospital in Paddington and in 1921 Fleming was made assistant director of the Inoculation Department. The following year he discovered lysozyme, a natural antibacterial enzyme which he found initially in human tears.

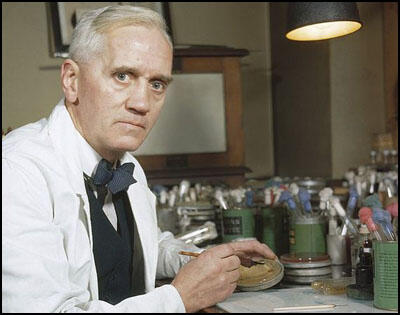

In 1928 Fleming was appointed as Professor of Bacteriology at the University of London. Later that year he was clearing out some old dishes in which he grew his cultures. On one of the mouldy dishes, he noticed that around the mould, the microbes had apparently been dissolved. He took a small sample of the mould and set it aside. He later identified it as of the penicillium family. He therefore named the anti-bacterial agent he had discovered penicillin.

Fleming published his findings in 1929 but it was not until during the Second World War that Howard Florey and Ernst Chain managed to isolate and concentrate penicillin. It was not until the end of the war that the antibiotic could be mass produced and was widely used. Fleming, Florey and Chain won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1945.

In October 1953 Fleming developed pneumonia. He was given an injection of penicillin. Fleming made a quick recovery and he later commented: "I had no idea it was so good."

Alexander Fleming died from heart failure on 11th March 1955. It was recently estimated that over 200 million lives have been saved by penicillin since 1945.