German Artists who Resisted Adolf Hitler

During the First World War several artists, including Helmut Herzfeld, Otto Dix and George Grosz, campaigned against the conflict. These men hated the strong nationalism that had emerged during the war in Germany. Helmut Herzfeld, shared this view and decided to change his name to John Heartfield in 1916 in "protest against German nationalistic fervour". Grosz decided to follow his example changed the spelling of his name to "de-Germanise" and internationalise his name – thus Georg became "George".

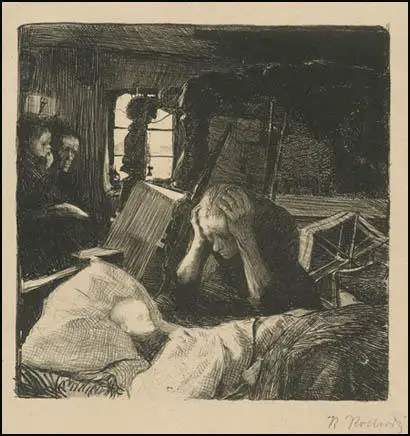

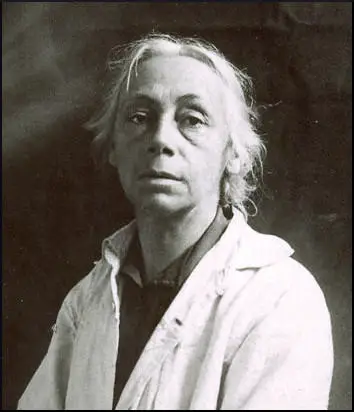

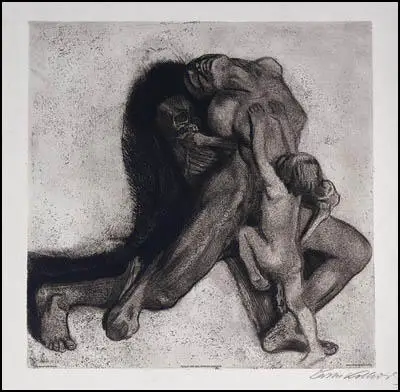

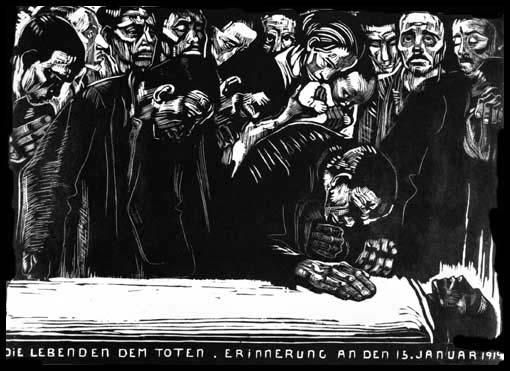

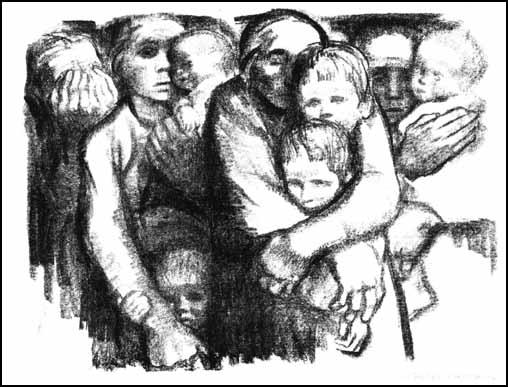

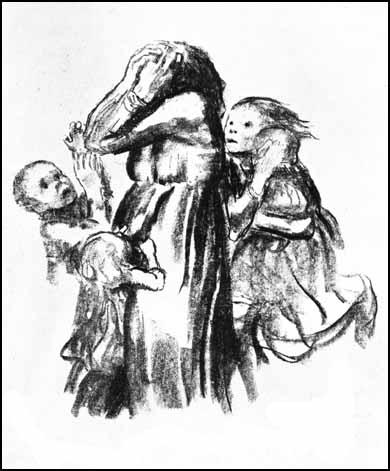

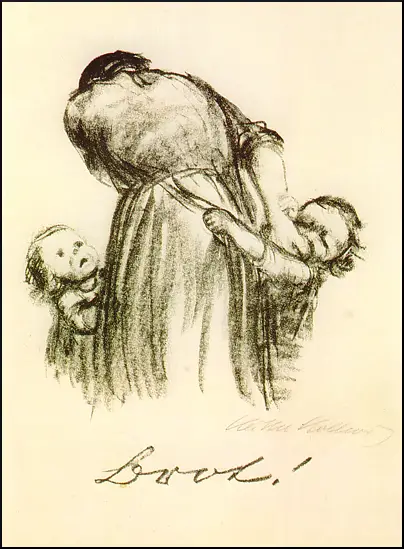

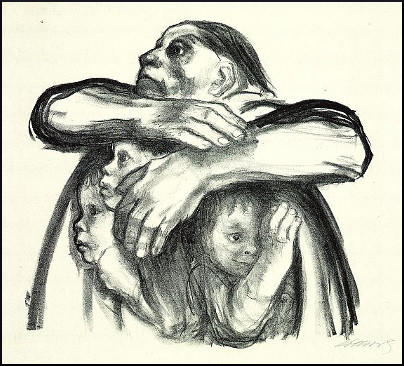

Käthe Kollwitz, an active member of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) was a mother during the First World War. On 23rd October, 1914, her son, Peter Kollwitz was killed at Dixmuide in Belgium on the Western Front. She later admitted that she had not argued against her sons joining the German Army "because there was the conviction that Germany was in the right and had the duty to defend herself." However, over the next few years she became an anti-war artist.

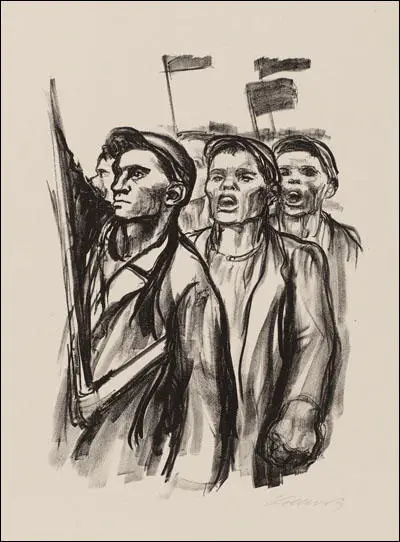

After the war Heartfield and Grosz joined the German Communist Party (KPD) and supported the German Revolution. It failed but Heartfield and Grosz refused to be beaten and joined forces with other left-wing artists, novelists, poets, playwrights, musicians, film and theatre directors, to resist nationalism and fascism. This included Bertolt Brecht, Erwin Piscator, Ernst Toller, Hannah Arendt, Günther Stern, Erich Mühsam, Kurt Weill, Hanns Eisler, Heinrich Mann, Erika Mann, and Heinrich Blücher.

This resistance was unsuccessful and most of them were either murdered on the orders of Adolf Hitler or managed to escape to the Soviet Union, the United States or Britain. Kollwitz did remain in Germany and although her art works were confiscated, because of her age, she was not sent to a concentration camp. Dix also remained in Germany but was not allowed to teach or display his art.

John Heartfield

Helmut Herzfeld was born in Berlin, Germany on 19th June, 1891. His father, Franz Held, was a socialist writer and his mother, Alice Stolzenberg, was a textile worker and a trade union activist. As a result of their politics the family was forced to flee to Switzerland in 1896. (1)

After leaving school at fourteen Herzfeld worked for a bookseller, Heinrich Heuss, in Wiesbaden. In 1907 he became an assistant to the painter, Hermann Bouffier, and two years later became a student at the School of Applied Arts in Munich. In 1912 Herzfeld started work as a designer in Mannheim for a year before moving to Berlin to study under Ernst Neumann at the Arts and Crafts School. (2)

Helmut Herzfeld was drafted into the German Army in 1915 but succeeds in evading military service. (3) Karl Liebknecht, the leader of the Spartacus League, a secret organization, published a pamphlet, The Main Enemy Is At Home! He argued: "The main enemy of the German people is in Germany: German imperialism, the German war party, German secret diplomacy. This enemy at home must be fought by the German people in a political struggle, cooperating with the proletariat of other countries whose struggle is against their own imperialists. We think as one with the German people – we have nothing in common with the German Tirpitzes and Falkenhayns, with the German government of political oppression and social enslavement. Nothing for them, everything for the German people. Everything for the international proletariat, for the sake of the German proletariat and downtrodden humanity." (4)

On 1st May, 1916, the Spartacus League decided to come out into the open and organized a demonstration against the First World War in Berlin. Helmut Herzfeld was in the crowd that day and heard Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg call for everyone to resist Germany's involvement in the war. Several of its leaders, including Liebknecht and Luxemburg were arrested and imprisoned. Wieland Herzfelde, said that the speeches at the rally had a great influence on his brother. It was at this point he decided to dedicate his art to politics. Wieland later wrote: "We are the soldiers of peace. No nation and no race is our enemy." (5) A pacifist and Marxist, Herzfeld, changed his name to John Heartfield in 1916 in "protest against German nationalistic fervour". (6)

Heartfield began contributing work to Die Neue Jugend, an arts journal published by his brother. His friend, George Grosz, who worked with him at the journal, later recalled how John Heartfield "developed a new very amusing style of using collage and bold typography". (7) Grosz helped him develop what became known as photomontage (the production of pictures by rearranging selected details of photographs to form a new and convincing unity). We... invented photomontage in my South End studio at five o'clock on a May morning in 1916, neither of us had any inkling of its great possibilities, nor of the thorny yet successful road it was to take. As so often happens in life, we had stumbled across a vein of gold without knowing it." (8)

In 1918 Heartfield and Grosz joined the newly formed German Communist Party (KPD) and over the next fifteen years produced designs and posters for the organization. (9) He participated in the First International Dada Fair of 1920. It is claimed that Heartfield had a major influence on the German Dada group that included Otto Dix, Max Ernst, Raoul Hausmann and Kurt Schwitters. (10)

Sergei Tretyakov was another artist linked to the Dada group. "Heartfield's first Dadaist photomontages are still marked by their abstract nature. Scraps of photograph and printed text are arranged not so much according to meaning but according to the aesthetic mood of the artist. The Dadaist period in Heartfield's work did not continue for long. He soon ceased to waste his artistic talents in abstract fireworks. His works became aimed shots... Soon no line could be drawn between his montages and his party work." (11)

Over the next few years Heartfield produced posters for the KPD. However, to earn a living he worked briefly as a set designer for Max Reinhardt and more consistently for the revolutionary theatre of Erwin Piscator. He also designed book jackets for the left-wing publishers, Malik Verlag. In 1923 Heartfield became editor of the satirical magazine, Der Knöppel. (12)

Bertolt Brecht first met Heartfield in 1924. He pointed out that John Heartfield soon became one of the most important European artists. "He works in a field that he created himself, the field of photomontage. Through this new form of art he exercises social criticism. Steadfastly on the side of the working class, he unmasked the forces of the Weimar Republic driving toward war." (13) Heartfield wrote: "Art and agitation are mutually exclusive". (14)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

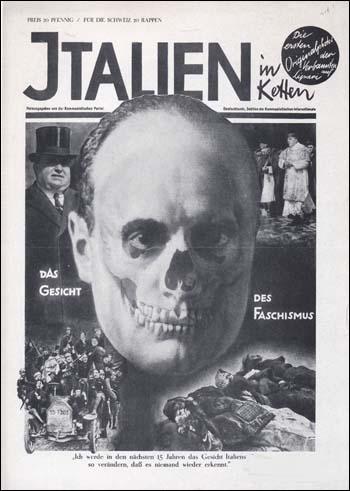

Wieland Herzfelde argued "he consciously placed photography in the service of political agitation". (15) In 1928 he created The Face of Fascism, a montage that dealt with the rule of Benito Mussolini which spread all over Europe with tremendous force. "A skull-like face of Mussolini is eloquently surrounded by his corrupt backers and his dead victims". (16)

Heiri Strub has pointed out that Heartfield made the decision to use his art for political causes. "Heartfield always considered his photomontages as artistic achievements. He took in stride the fact that he was not recognized by contemporary art critics. The works he created for dissemination in huge editions had no value in the art market. Directing his political charges at the masses, he could scarcely count on a sympathetic reaction from bourgeois art collectors. The worker, however, for whom he intended his photomontages, understood their revolutionary content, but assigned no artistic value judgment to them." (17)

John Heartfield began working for the socialist magazine, Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (AIG) in 1929. During this period it became the most widely socialist pictorial newspaper in Germany. Circulation reached 350,000 in 1930. (18) Zbyněk Zeman has pointed out that at this stage Heartfield concentrated his attack on "Prussian militarism and the large-scale industries and industrialists who supplied it with arms". (19)

The German novelist, Heinrich Mann, was one of those who saw the significance of the magazine: "The Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung is one of the best of current picture newspapers. It is full in its coverage, technically good, and, above all, unusual and new... Aspects of daily life are seen here through the eyes of the worker, and it is time that this happened. The pictures express complaints and threats reflecting the attitude of the proletariat - but at the same time this proves their self-confidence and their energetic activity to help themselves. The self-confidence of the proletariat in this weary part of the world is most heartening." (20)

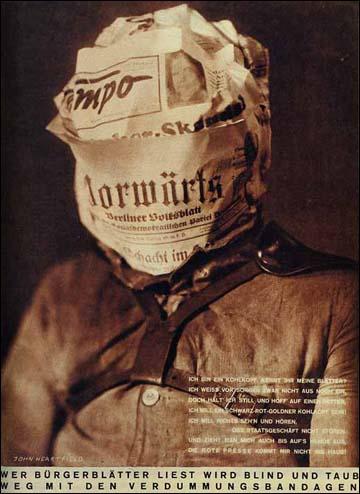

become blind and deaf, Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (AIG) (February 1930)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Heiri Strub worked with Heartfield at the magazine. "Heartfield's high demands of quality made collaboration with him difficult. His long-time colleague, the photographer Janos Reismann, related how Heartfield constantly demanded new pictures until he saw his idea realized... With photographic tricks and painting Heartfield arranged the parts of the photo to fit together seamlessly. With extraordinary care he devised his adhesive picture, so that after final retouching it went straight to the printer. Since the AIZ was produced using the highly sensitive copperplate photogravure method, errors were as evident as the artist's real intention. Heartfield's respect for the skills of others was so great that he himself did not do the photography, and he left the retouching to others, but always under his stringent supervision." (21)

Louis Aragon has argued: "John Heartfield is one of those who expressed the strongest doubts about painting, especially its technical aspects... As we know, Cubism was a reaction of painters to the invention of photography. The photograph and the cinema made it seem childish to them to strive for verisimilitude. By means of these new technical accomplishments they created a conception of art which led some to attack naturalism and others to a new definition of reality. With Leger it led to decorative art, with Mondrian to abstraction, with Picabia to the organization of mundane evening entertainment. But toward the end of the war, several men in Germany (Grosz, Heartfield, Ernst) were led through the critique of painting to a spirit which was quite different from the Cubists, who pasted a piece of newspaper on a matchbox in the middle of the picture to give them a foothold in reality. For them the photograph stood as a challenge to painting and was released from its imitative function and used for their own poetic purpose." (22)

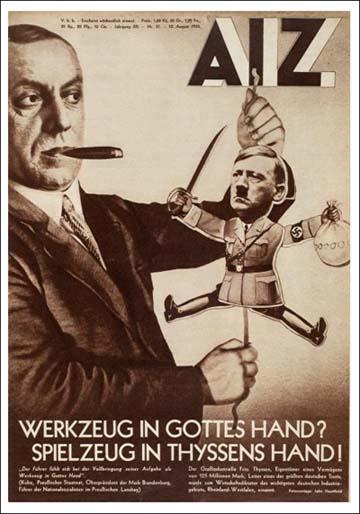

John Heartfield's main target in the early 1930s was Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party. His work often appeared on the front cover of AIG. In 1930 the magazine published twelve of his photomontages. This included one that showed Fritz Thyssen, the owner of United Steelworks, a company that controlled more that 75 per cent of Germany's ore reserves and employed 200,000 people. In the photomontage, Thyssen is shown working Hitler as a puppet.

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

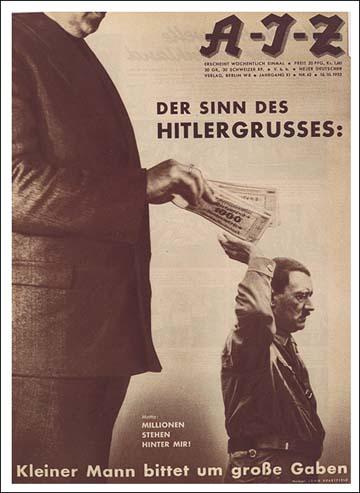

In 1932 Heartfield produced 18 photomontages for AIG. The most famous of these appeared just before the November 1932 General Election. Hitler is showed standing in front of a large man who represents big business. The man is handing over money to Hitler. Printed underneath are the words: "Motto: Millions stand behind me! A little man asks for gifts". Heartfield's friend, Oskar Maria Graf, commented, that all his work was now politically motivated, "the intolerable aspect of events is the motor of his art". (23)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Richard Carline was an English artist who met him during this period: "Slight and little more than five feet tall, Heartfield displayed the unmistakable traits of genius - single-minded and purposeful. With his intense, unpretentious, and uninhibited personality, he warmed toward everyone he met without regard for class or background. He would talk to animals as if they were humans." (24)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

In the election in November 1932 the Nazi Party won 230 seats, making it the largest party in the Reichstag. The German National Party, won nearly a million additional votes. However the German Social Democrat Party (133) and the German Communist Party (89) still had the support of the urban working class and Hitler was deprived of an overall majority in parliament. In numerical terms, the socialist parties obtained 13,228,000 votes compared to the 14,696,000 votes recorded for the Nazis and the German Nationalists. (25)

Soon after Hitler became chancellor in January 1933 he announced new elections. Hermann Goering called a meeting of important industrialists where he told them that the election would be the last in Germany for a very long time. He explained that Hitler "disapproved of trade unions and workers' interference in the freedom of owners and managers to run their concerns." (26) Goering added that the NSDAP would need a considerable amount of of money to ensure victory. Those present responded by donating 3 million Reichmarks. As Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary after the meeting: "Radio and press are at our disposal. Even money is not lacking this time." (27)

On 27th February, 1933, the Reichstag caught fire. When they police arrived they found Marinus van der Lubbe on the premises. After being tortured by the Gestapo he confessed to starting the Reichstag Fire. However he denied that he was part of a Communist conspiracy. Hermann Goering refused to believe him and he ordered the arrest of several leaders of the German Communist Party (KPD).

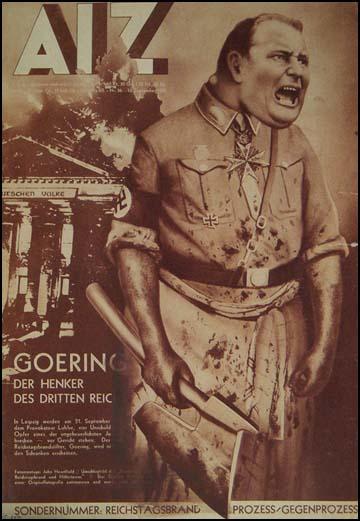

When Hitler heard the news about the fire he gave orders that all leaders of the German Communist Party should "be hanged that very night." Paul von Hindenburg vetoed this decision but did agree that Hitler should take "dictatorial powers". KPD candidates in the election were arrested and Hermann Goering announced that the Nazi Party planned "to exterminate" German communists. John Heartfield responded to these events by producing Goering the Executioner of the Third Reich. It shows the "human bloodhound with his axe standing in front of the burning parliament." (28)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Behind the scenes Goering, who was minister of the interior in Hitler's government, was busily sacking senior police officers and replacing them with Nazi supporters. These men were later to become known as the Gestapo. Goering also recruited 50,000 members of the Sturm Abteilung (SA) to work as police auxiliaries. Goering then raided the headquarters of the German Communist Party (KPD) in Berlin and claimed that he had uncovered a plot to overthrow the government. Leaders of the KPD were arrested but no evidence was ever produced to support Goering's accusations. He also announced he had discovered a communist plot to poison German milk supplies. (29)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Thousands of members of the Social Democrat Party and trade union activists were arrested and sent to recently opened concentration camps. Left-wing election meetings were broken up by the Sturm Abteilung (SA) and several candidates were murdered. Newspapers that supported these political parties were closed down during the election. Although it was extremely difficult for the opposition parties to campaign properly, Hitler and the Nazi party still failed to win an overall victory in the election on 5th March, 1933. The Nazi Party received 43.9% of the vote and only 288 seats out of the available 647. The increase in the Nazi vote had mainly come from the Catholic rural areas who feared the possibility of an atheistic Communist government.

Adolf Hitler ordered the arrests of all those artists that had criticized him during his rise to power. (30) On 16th April, 1933, members of the Sturmabteilung (SA) arrived at Heartfield's apartment. Heartfield had been warned about what was going to happen and he managed to flee to Prague. This now became the place where AIG was published. That year Heartfield produced 35 front-covers. However, it was very difficult to smuggle the magazine back to Germany and circulation dropped dramatically from the 500,000 copies that were being sold before Hitler took power. (31)

All forms of mass communication were now controlled in Nazi Germany. The man in overall charge was Dr. Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda. Lists were drawn up of books the Nazis believed contained "un-German" ideas and then all available copies were publically destroyed. The Nazis were especially hostile to works produced by left-wing writers like Bertolt Brecht and Ernst Toller.

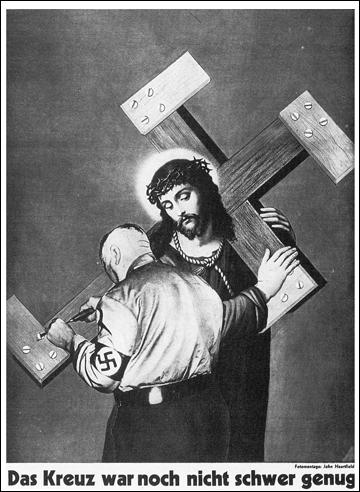

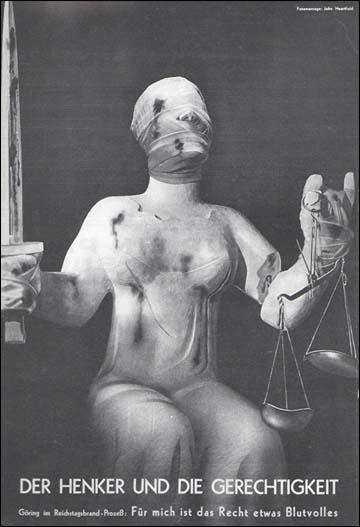

Heartfield was especially upset by the passing of the Enabling Bill. This banned the German Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party from taking part in future election campaigns. This was followed by Nazi officials being put in charge of all local government in the provinces (7th April), trades unions being abolished, their funds taken and their leaders put in prison (2nd May), and a law passed making the Nazi Party the only legal political party in Germany (14th July). This situation motivated Heartfield to produce the Executioner and Justice on 30th November 1933.

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Adolf Hitler became increasingly annoyed with John Heartfield's photomontages published in Prague (35 in 1933) and he told the government in Czechoslovakia to ban his work. In May 1934 the authorities agreed to Hitler's demands. This created a great deal of controversy and the French artist, Paul Signac, urged international action. He wrote a letter to Heartfield's supporters in Prague: "My whole life long I have been fighting for the freedom of art... I am prepared to contribute my share in organizing a French exhibition of our friend's works... The club is poised for battle against the freedom of the spirit. Let us unite to defend ourselves." (32)

The French poet, Louis Aragon, argued in Commune Magazine: "John Heartfield today knows how to salute beauty. He knows how to create those images which are the beauty of our rage since they represent the cry of the people - the representation of the people's struggle against the brown hangman with his craw crammed with gold pieces. He knows how to create these realistic images of our life and struggle arresting and gripping for millions of people who themselves are a part of that life and struggle. His art is art in Lenin's sense for it is a weapon in the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat." (33)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Heartfield's friends in Europe helped to get his work published. Several photomontages on the Spanish Civil War were published. This included Madrid 1936, a work of art that dealt with the Siege of Madrid. Another poster, The Mothers to their Sons in Franco's Service, was published in December 1936. On the poster it said: "For what you were hired. Whom you are hounding. So permit us mothers to tell you: We grieve for you, young ones. No, we did not raise you to murder. You are allowing yourselves to be abused. You have been betrayed!" (34)

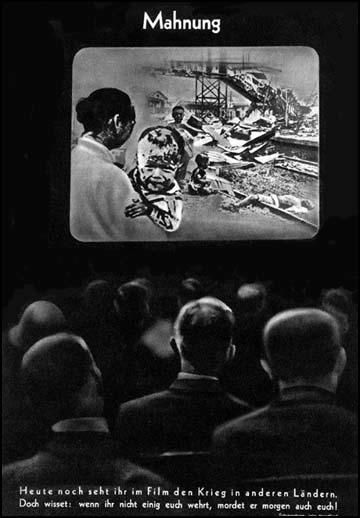

In October 1937 John Heartfield published Warning. In the photomontage an audience looks at a scene of horror caused by Japanese air raids in Manchuria. "Heartfield's pastiche layers in several rows of faceless male heads, backs towards us, beneath the frontal stare of an on-screen victim in the violent newsreel footage at which they are staring: a Chinese mother holding a bloodied child in outsized close-up." It had the caption: "Today you see a film of war in other countries. But remember, if you don't unite to resist it now, tomorrow it will kill you, too!" It was a prediction that was to come true within two years. (35)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

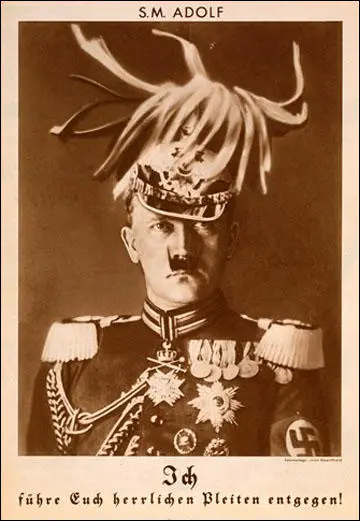

When Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of Czechoslovakia after the Munich Agreement of 1938 John Heartfield was forced to flee the country. In December he arrived in London. Over the next few months his work appeared in the Reynolds News and Lilliput. He spoke at political rallies, organized anti-Fascist groups, and took part in a successful political cabaret, Four and Twenty Black Sheep. On 23rd September, 1939, Picture Post used one of Heartfield's earlier photomontages, His Majesty Adolf, which showed Hitler wearing the Kaiser's uniform and moustache, on its front-cover. (36)

On the outbreak of the Second World War he was interned with fellow refugees who had suffered under the Nazis and were now dubbed "enemy aliens". He was suffering from poor health and he was eventually released but he was not asked to work for the British government. "His whole ambition was to make people fully aware of the menace of Fascism and to expose the Nazi tyranny through his work as an artist... The powerful contribution he might have made toward the Allied victory through his mastery of satire was not acceptable to the British authorities. They were highly suspicious of art, especially experimental forms of art by a German refugee." (37)

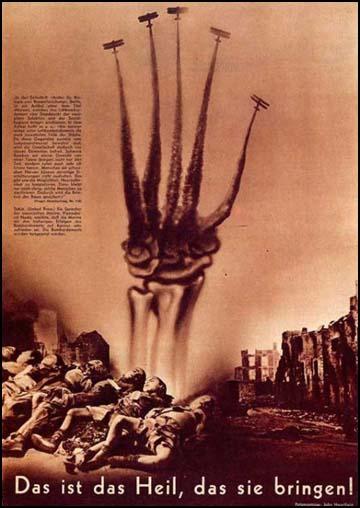

One of John Heartfield most powerful photomontages, This is the Salvation that they Bring!, that had originally been published in protest against the Spanish Civil War, was republished during the Blitz. On the poster it had an extract from an article that appeared in the Nazi Party funded Berlin Journal for Biology and Race Research: "The densely populated sections of cities suffer most acutely in air raids. Since these areas are inhabited for the most part by the ragged proletariat, society will thus be rid of these elements. One-ton bombs not only cause death but also very frequently produce madness. People with weak nerves cannot stand such shocks. That makes it possible for us to find out who the neurotics are. Then the only thing that remains is to sterilize such people. Thereby the purity of the race is guaranteed." (38)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

John and his third wife, Gertrud (Tutti) Heartfield, settled in Hampstead. During the war he was an active member of the Artists International Association and contributed to its exhibitions. Heartfield also designed book jackets for the London publisher Lindsay Drummond and Penguin Books. (39)

John Heartfield and his wife moved to Leipzig in East Germany in August 1950. Together with his brother, Wieland Herzfelde, he worked for publishers and organizations in the GDR. He also designed scenery and posters for the Berliner Ensemble and the Deutsches Theatre. However, as Peter Selz has pointed out, he found it difficult to produce political photomontages. "While he was celebrated as a cultural leader, his chief idiom, photomontage, was still suspect during the 1950s among the more orthodox advocates of socialist realism." (40)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Heartfield continued to be a peace activist and on 9th June 1967, at the time of an exhibition of his works at the Stockholm Modern Museum, he wrote about the dangers posed by the Vietnam War. "Since we are living in the nuclear age, a third world war would mean a catastrophe for all mankind, a catastrophe the full extent of which cannot be possibly be imagined.... The war of extermination against the Vietnamese people, fighting heroically for their existence... Now there is a war in the Middle East! Shortly before that, a monarchist-fascist putsch smothered every democratic political movement in Greece. The flames are licking at your doorstep! Today peace-loving men of all nations must work together even more closely; must mobilize all the resources to strengthen and preserve world peace, since powerful rulers again lust for war." (41)

The later years of life were devoted to designing brilliant costumes, stage sets, and stage projection for the East German Theatre. John Heartfield died in Berlin on 26th April, 1968. (42)

George Grosz

Georg Ehrenfried Grosz, the son of a pub owner, was born in Berlin, Germany, on 26th July, 1893. He was brought up by devout Lutheran parents. His father was warden at the local masonic hall. "My father himself used sometimes to draw on the large cardboard sheets pinned to the square table... I can still remember sitting on his lap and watching all sorts of creatures come to life under his hand." (43)

His father died in 1901 and the family moved to Berlin. "My mother and aunt sewed blouses for some big concern - hard work that brought in little cash. True, living was cheap, and we had enough of the bare necessities, but we were constantly beset by money worries now.... We were living in a real working-class district, though I did not realize it at the time." (44)

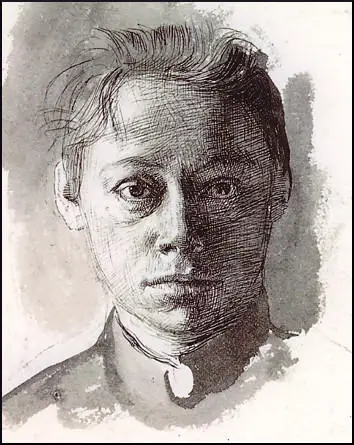

Grosz was a talented artist and began attending a weekly drawing class taught by a local painter. In 1909 he became a student at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, where his teachers were Robert Sterl and Osmar Schindler. In 1911 he moved to the Berlin College of Arts and Crafts where he studied under Emil Orlik. (45) During this period Grosz had his first caricatures published in the Berliner Tageblatt. (46)

On the outbreak of the First World War Grosz was conscripted into the German Army. "What can I say about the First World War, a war in which I served as an infantryman, a war I hated at the start and to which I never warmed as it proceeded? I had grown up in a humanist atmosphere, and war to me was never anything but horror, mutilation and senseless destruction, and I knew that many great and wise people felt the same way about it. At the outbreak of hostilities, Germany was in the throes of a kind of mass delirium, but when the first flush of that was over there was nothing to take its place." (47)

A strong opponent of the war, he was eventually released as unfit for duty. Grosz wrote to a friend "The time I spent in the stranglehold of militarism was a period of constant resistance - and I know there was not one thing I did which did not utterly disgust me... I have one dream: perhaps there will, after all, be changes, rebellions, perhaps one day international socialism which has lost its backbone will gather strength enough for an open uprising... It is an absurd dream, no more... to the slaughterhouse!" (48)

However, the following year, desperate for soldiers, Grosz was called up again. Kept from frontline action, Grosz was used to transport and guard prisoners of war. "In 1916 I was discharged from military service, or rather, given a sort of leave of absence on the understanding that I might be recalled within a few months. And so I was a free man, at least for a while. The collapse of Germany was only a matter of time. All the fine phrases were now no more than stale, rank printer's in on brown substitute paper. I watched it all from my studio in Sudende, living and drawing in a world of my own. I drew soldiers without noses; war cripples with crab-like limbs of steel; two medical orderlies tying a violent infantryman up in a horse blanket; a one-armed soldier using his good hand to salute a heavily bemedalled lady who had just passed him a biscuit; a colonel, his fly wide open, embracing a nurse; a hospital orderly emptying a bucket full of pieces of human flesh down a pit." (49)

Grosz hated the strong nationalism that had emerged during the war in Germany. Grosz's close friend, the artist, Helmut Herzfeld, shared this view and decided to change his name to John Heartfield in 1916 in "protest against German nationalistic fervour". (50) Grosz decided to follow his example changed the spelling of his name to "de-Germanise" and internationalise his name – thus Georg became "George". (51)

In the middle of 1917 Grosz was recalled to the German Army. "My new duties were to train recruits and to transport and guard prisoners of war. But I had enough and one night they found me semi-conscious, head-first in the latrine. I spent some time in hospitals after that. Whenever I had a moment to spare I would vent my spleen in sketches of everything about me that I hated, either in my notebook or on sheets of writing paper; the brutal faces of my comrades, badly mutilated war cripples, arrogant officers, lascivious nurses." (52)

Grosz had joined the Spartacus League, an anti-war organization, led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. He now considered himself a Marxist and a pacifist. He was terribly unhappy in the army and in 1917 he tried to commit suicide and Grosz was placed in an army hospital. According to Grosz, it was decided to execute him but he was saved by the intervention of one of his wealthy patrons, Count Harry Clemens Ulrich Kessler. Grosz was now diagnosed as suffering from shell-shock and was discharged from the German Army. (53)

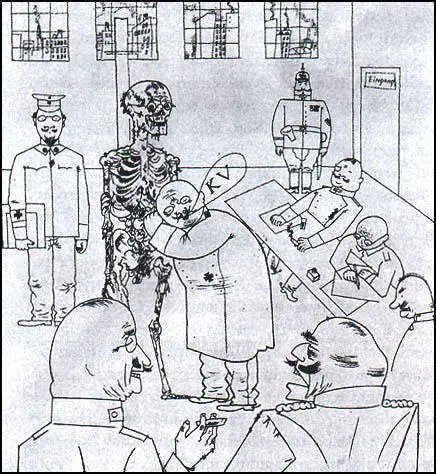

The war had a major impact on his art. George Grosz joined with John Heartfield in protesting about the German wartime propaganda campaign against the allies. He was also totally opposed to the war continuing when it was clear that victory was impossible. His most powerful anti-war drawings during this period, was such Fit for Active Service (1918), in which a well-fed doctor inspecting a skeleton with an ear trumpet and pronouncing a skeleton, "KV" fit for duty. Unconcerned with the diagnosis, the surrounding officers appear either bored or absorbed in other matters. (54)

The German government of Max von Baden asked President Woodrow Wilson for a cease-fire on 4th October, 1918. "It was made clear by both the Germans and Austrians that this was not a surrender, not even an offer of armistice terms, but an attempt to end the war without any preconditions that might be harmful to Germany or Austria." This was rejected and the fighting continued. On 6th October, it was announced that Karl Liebknecht, who was still in prison, demanded an end to the monarchy and the setting up of Soviets in Germany. (55)

By the 8th November, workers councils took power in virtually every major town and city in Germany. This included Bremen, Cologne, Munich, Rostock, Leipzig, Dresden, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Nuremberg. Theodor Wolff, writing in the Berliner Tageblatt: "News is coming in from all over the country of the progress of the revolution. All the people who made such a show of their loyalty to the Kaiser are lying low. Not one is moving a finger in defence of the monarchy. Everywhere soldiers are quitting the barracks." (56)

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, a member of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) established a Socialist Republic in Bavaria. Several leading socialists arrived in the city to support the new regime. This included Erich Mühsam, Ernst Toller, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Eisner also wrote to Gustav Landauer inviting him to Munich: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution. (57)

Konrad Heiden wrote: "On November 6, 1918, he (Kurt Eisner) was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds." (58)

George Grosz was a supporter of the German Revolution. Grosz was especially hostile to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party, and the leader of the government. "President Ebert had his beard trimmed, looked more and more like a managing director and changed his democratic felt hat for a shiny topper. Secretary of State Otto Meissner, the republic's master of ceremonies, made sure that he performed the office of his illustrious predecessors with due dignity and did not commit too many proletarian solecisms in the pursuit of his exalted duties." (59)

The Spartacus League published a leaflet that claimed: "The Ebert-Scheidemann government intends, not only to get rid of the last representative of the revolutionary Berlin workers, but to establish a regime of coercion against the revolutionary workers." It is estimated that over 100,000 workers demonstrated against the sacking of Eichhorn the following Sunday in "order to show that the spirit of November is not yet beaten." (60)

By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, who refused to flee the city, and were captured on 16th January and taken to the Freikorps headquarters. "After questioning, Liebknecht was taken from the building, knocked half conscious with a rifle butt and then driven to the Tiergarten where he was killed. Rosa was taken out shortly afterwards, her skull smashed in and then she too was driven off, shot through the head and thrown into the canal." (61)

Friedrich Ebert, the president of Germany, arranged for 30,000 Freikorps, under the command of General Burghard von Oven, to take Munich. At Starnberg, some 30 km south-west of the city, they murdered 20 unarmed medical orderlies. The Red Army knew that the choice was armed resistance or being executed. The Bavarian Soviet Republic issued the following statement: "The White Guards have not yet conquered and are already heaping atrocity upon atrocity. They torture and execute prisoners. They kill the wounded. Don't make the hangmen's task easy. Sell your lives dearly." (62)

Grosz explained that the experience of war had a major impact on political consciousness: "Yes, everyone was now allowed his say. But having been used to taking their marching orders for years, all they could do was strut about a little less stiffly perhaps but also less smartly than before. The people obviously missed the sharp voice of command, and as for their vaunted freedom, they were at a complete loss what to do with it. Each one had a political view, compounded of fear, envy and hope - but what good were these views to anyone if no leader came forward to put them into practice? And as the people themselves refused to shoulder the responsibility or the blame, they had to look for a scapegoat. One was ready to hand: the Jew." (63)

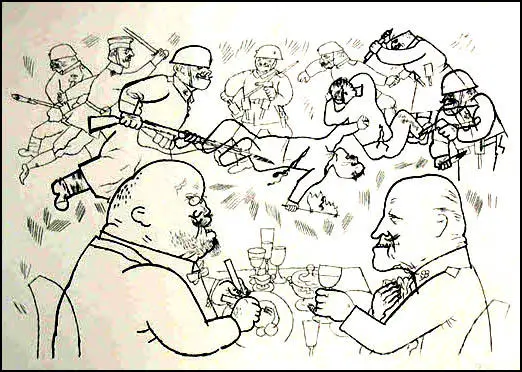

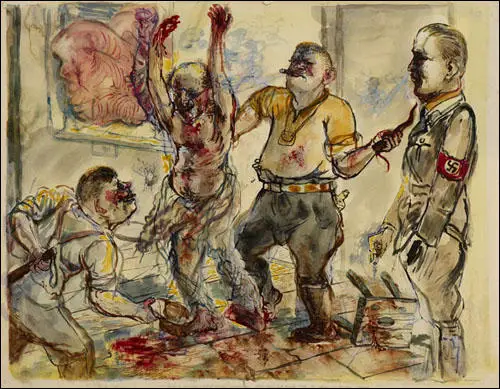

Zbyněk Zeman has pointed out in his book, Heckling Hitler: Caricatures of the Third Reich (1984) that Grosz's art was deeply influenced by the political situation: "The brutality and confusion of Germany after World War I were strikingly reflected in George Grosz's drawings. His drawing Communists Fall and Shares Rise refers to Bloody Week (10-17 January 1919) when regular and irregular troops of the Republic crushed the communist 'Spartacists', who had occupied the imperial palace in Berlin." (64)

Uwe M. Schneede, the author of George Grosz: His Life and Work (1979) has pointed out that the drawing was inspired by a phrase used by Rosa Luxemburg during the First World War: "Grosz links military action against the workers with the economic interests of the ruling classes. These drawings are comments on the Marxist interpretation of history, made wholly convincing through the powerful characterisation of the facial expressions of those who order the murders and those who carry them out." (65)

George Grosz began contributing work to Die Neue Jugend, an arts journal published by his brother. His work was influenced by his friend, John Heartfield who had "developed a new very amusing style of using collage and bold typography". (66) Grosz helped him develop what became known as photomontage (the production of pictures by rearranging selected details of photographs to form a new and convincing unity). We... invented photomontage in my South End studio at five o'clock on a May morning in 1916, neither of us had any inkling of its great possibilities, nor of the thorny yet successful road it was to take. As so often happens in life, we had stumbled across a vein of gold without knowing it." (67)

In 1920 George Grosz, John Heartfield and Raoul Hausmann organised the Erste Internationale Dada-Messe in the Berlin gallery owned by Otto Burchard. It was a comprehensive manifestation of Dada (a movement consisted of artists who rejected the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern capitalist society, instead expressing nonsense, irrationality, and anti-bourgeois protest in their works). Among the 174 works in the exhibition were pictures by Grosz, Heartfield, Hausmann, Otto Dix, Max Ernst, Hannah Höch and Rudolf Schlichter. "The text on the panels accompanying each exhibit was partly Dadaist-polemical, partly political." (68)

In 1922 Grosz traveled to the Soviet Union with the Danish writer Martin Andersen Nexø. Upon their arrival in Murmansk they were briefly arrested as spies; after their credentials were approved, they were allowed to meet with Lenin and other revolutionary leaders such as Grigory Zinoviev and Anatoly Lunacharsky. Grosz's six-month stay in the Soviet Union left him unimpressed by what he had seen. (69) On his return he left the KPD, but he remained a committed socialist revolutionary. (70) After spending time in the Soviet Union he could "no longer subscribe to the positive image of the happy, liberated worker". (71)

Grosz wrote in his autobiography about how the political situation had changed the role of the artist: “All moral codes were abandoned. A wave of vice, pornography and prostitution enveloped the whole country.... The streets became ravines of manslaughter and cocaine traffic, marked by steel rods and bloody, broken chair legs.” (72) In 1923 he published the book, Ecce Homo. It contained 84 offset lithographs and 16 watercolor reproductions. "The book is a vicious satire of post-war German life, with politicians, capitalists, prostitutes, mutilated veterans, beggars, and drunks in various states of despair, lust, and rage. The German government banned it and Grosz was put on trial for public offense. While he was clearly influenced by the Cubist, Bauhaus, and Fauvist movements, in Ecce Homo, Grosz’s raw, angry style is distinctly his own." (73)

Lisa Small has argued: "Cynicism and disillusionment with the government and militarism permeates the work of George Grosz, an incisive caricaturist, satirist, and one of the most influential graphic artists to be associated with Expressionism, New Objectivity, and Dada. An ardent communist and supporter of the working class, Grosz expressed his disdain for the right wing capitalist and military ruling classes in a caustic portfolio of lithographs he made after WWI ironically titled God With Us after the nationalistic motto inscribed on every German soldier’s belt buckle. The print For German Right and German Morals presents five brutish, malevolent, and corrupt specimens of the German military; the squat and thuggish officer in the center, whose holster makes obvious reference to his genitals, crushes a flower under his boot." (74)

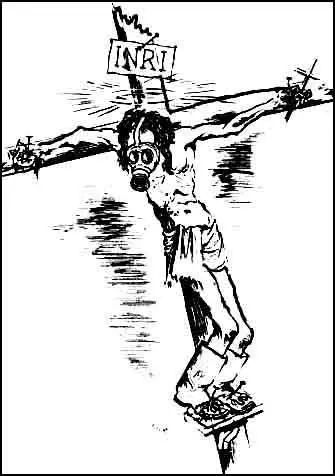

In one case Grosz was charged with blasphemy for his cartoon of Christ in a gas-mask. Mary M. Lane claimed that this was a warning against radical far-right religious views... a work that shows Jesus Christ nailed to the cross wearing combat boots and a gas mask - a criticism of politicizing Christianity that drew praise from pacifist Quakers in the United States." (75)

Frank Whitford has argued that the work of artists such as George Grosz and Otto Dix developed what became known as the New Realism. "They had grown weary of the years of hectic experimentation that had preceded the war and that they were tired of all kinds of art that were highly subjective, metaphysical, esoteric and accessible only to an elite. They wanted to return to subjects that were familiar to everyone, painted in a way which everyone could understand. Some of them were content simply to mirror common experience of mundane things. Others, more politically inspired, preferred to angle the mirror so that the dark side of society was revealed. All of these artists cultivated a painstakingly realistic style which emulated the smooth, anonymous surface of the photograph." (76)

George Grosz gained support from Bertolt Brecht: "Let us suppose that the trial of Socrates is over. We organize a short witches' trial, where the judges are armoured knights who condemn the witch to the stake. Then the trial of George Grosz begins, but we forget to remove the knights from the stage. When the indignant prosecutor storms at the artist for having insulted our mild and compassionate God... the knights... are moved to applause." (77)

George Grosz and John Heartfield joined with Paul Levi, Willie Munzenberg, Clara Zetkin, Ernst Toller, Walther Ulbricht, Heinrich Blücher, Julian Marchlewski, Ernst Thälmann, Hermann Duncker, Hugo Eberlein, Paul Frölich, Wilhelm Pieck, Franz Mehring, and Ernest Meyer. to form the German Communist Party (KPD). Over the next fifteen years Grosz and Heartfield produced designs and posters for the organization. (78) Grosz participated in the First International Dada Fair of 1920. Grosz's collected drawings, The Face of the Ruling Class was published in 1921. It is claimed that Grosz and Heartfield had a major influence on the German Dada group that included Otto Dix, Max Ernst, Raoul Hausmann and Kurt Schwitters. (79)

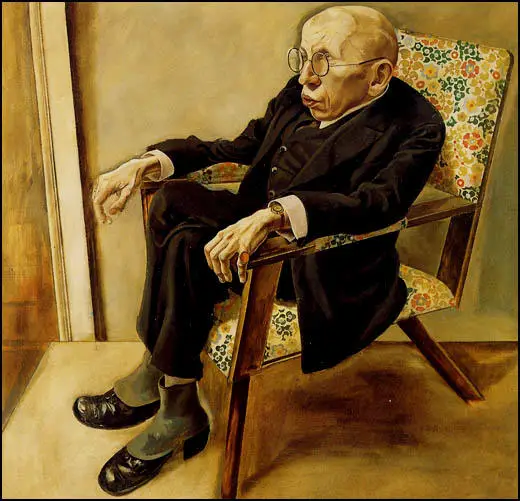

In 1925 Grosz started painting in oils again. The subject of his first portrait was Max Herrmann-Neisse, a poet and fellow left-wing activist. Herrmann-Neisse became a great supporter of the work of Grosz. He later wrote: "I always felt perfectly at home with George Grosz. We had roughly the same convictions and moods... We were both poets as well as cynics, at once correct and anarchic. I sat for him innumerable times with the greatest of pleasure, feeling blissfully secure in his studio... Leaning against the walls were the pictures which for the decent citizen represented a veritable chamber of horrors. The painstaking way in which he worked on my portrait demonstrated how very seriously he took his work." (80)

George Grosz disliked post-war Germany and the excesses of city life. "My drawings and paintings were done as an act of protest; I was trying by means of my work to convince the world that it is ugly, sick and hypocritical... I drew drunks, people throwing up, men shaking their fists at the moon as they cursed it, the murderers of women, playing at cards while sitting on a crate in which the murder victims could be seen... I drew a man looking around him fearfully, washing his hands, which had blood on them." (81)

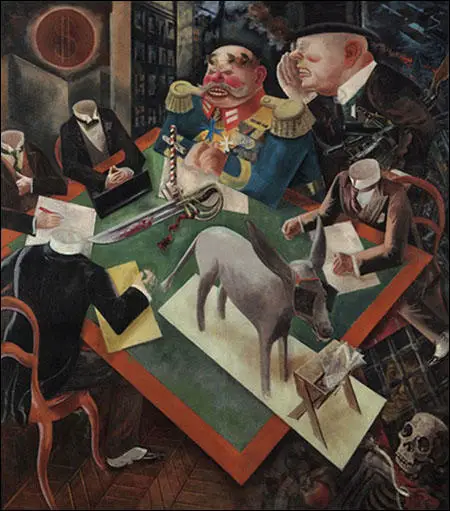

Grosz’s first large painting was Eclipse of the Sun (1926). The painting is a scathing indictment of the military-industrial complex and of materialism: We see two men on the right of the picture; one is covered in medals and decorations and huge epaulettes, obviously a military man; the one next to him on the other hand looks more like a businessman or profiteer wearing a bowler hat and with a train of guns mounted on his suit. The other people in the picture have no heads, as if they were stuffed shirts made to do anything except what they are told." (82)

In 1928 Grosz was charged with blasphemy. During his trial he said: "It is a long German tradition which I carry on. When the times are very troubled, when the foundations are shaken, the artist cannot stand aside, especially not the talented artist with his greater sensitivity. That is why, without wanting to, he will be political... There is much injustice and it is a certain inner compulsion which has driven me to the side of those who are struggling against this injustice. I think there is too much brutality and not enough love. Wherever one turns, there are empty words, injustice and brutality. Surely there exists a minority which feels that too. To tell the truth, these feelings are alive, they animate any man who is of a satirical turn of mind." (83)

Grosz also designed sets or costumes for seven productions at Berlin theatres including those of Erwin Piscator. Grosz wrote in his journal that "Erwin has created a great new era for the graphic artist to work in, a veritable graphic arena, more tempting for graphic artists of today than all that stuffy aesthetic business or the hawking around of drawings in bibliophile editions for educated nobs... What a medium, though, for the artist who wants to speak to the masses, purely and simply. Naturally a new area requires new techniques, a new clear and concise language of graphic style - certainly a great opportunity for teaching discipline to the muddleheaded and confused!" (84)

It has been argued that Grosz became one of the most important artists in the world during this period: "Grosz's work as graphic artist, painter, and designer of costumes and stage sets, along with his involvement as co-founder and advocate of new artistic movements, teacher, writer, and political commentator, all underline his versatility. At the centre of his oeuvre, however, stand his political, critically-engaged drawings; it is through them that Grosz became famous... For long phases within his creative output, Grosz saw himself less as an artist than as an aggressive pictorial journalist." (85)

George Grosz, along with John Heartfield and Karl Arnold, were the first artists to realise the dangers of Adolf Hitler. Originally drawn in 1923, but not published until 1930, Hitler, the Saviour, is a change in style for Grosz: "Drawn in the year of Hitler's failed putsch in Bavaria in 1923, told a different story. Grosz's Hitler is a more human figure but divided against himself... who had a necklace of teeth around his neck and wore a furry shift, would not have plastered his hair down so carefully, and cut his moustache in such an odd way. There was a smug and belligerent expression on Hitler's face, an expression which should not have been on the face of one of the heroes of the great German myth... There was a dangerous, downward curve about Hitler's mouth. Grosz was pointing out Hitler's mysticism and its underlying banality, in a way only possible for someone who was familiar with the phenomenon, having observed it closely in its own setting." (86)

In 1930 George Grosz illustrated The Three Soldiers, a children's book by Bertolt Brecht. "The soldiers realised 'that it was a war of the rich and the rich made war only in order that the rich should grow still richer'. The soldiers were called Hunger, Disaster and Disease. They travel across the country, killing as they go along. When they get to Moscow they are shot because there people are unwilling to put up with wretchedness." (87)

Grosz continued to grow worried about the growth in the Nazi Party: "Perhaps what lies ahead of us is the new Middle Ages. At least to me humanist ideas seem to be dying out, just as... human rights are no longer greatly valued. Rather it would appear that hand in hand with the progress of civilisation goes a sound contempt for human life." (88) However, most Germans dismissed Grosz’s anti-Nazi work as hyperbolic and offensive to Christianity, a feeling that far-right activists exploited to distract from what he was saying. One night in the early 1930s, Grosz discovered an iron pipe at his front door with a note attached. “This is for you, you old Jew-Pig, if you keep going with what you’re doing." (89)

In June 1932, he accepted an invitation to teach the summer semester at the left-wing Art Students League in New York City . In October 1932, Grosz returned to Germany, but on January 12, 1933, he and his family emigrated to the United States. "On 30th January, 1933, Hitler became Germany's Reich Chancellor... Soon letters arrived from which I learnt that they had been looking for me in my empty flat in Berlin, and also in my studio. I venture to doubt whether I should have got away with my life." (90)

Grosz became one of over 2,500 artists and writers to leave Nazi Germany. Grosz continued to attack Hitler in his work. This includes the drawing, He is a Writer (1933). In this drawing Grosz depicts the SA searching through the belongings of a terrified suspect: "He is a writer", they declare. It has been suggested that Hitler's almost fanatical hatred of intellectuals and the educated middle-class can perhaps be traced to his own academic failure and early rejecting of intellectual discipline." (91)

According to Uwe M. Schneede: "Letters, reports and drawings from his early days in America bore witness to Grosz's fascination with the casualness of the Americans, with their shows, their fashions, the speed of their lives... There are many sketches and drawings in which he registered these fresh impressions, his determined turning to American themes running parallel with a total turning away from the political works he had created in Germany... Grosz wanted to become an American illustrator but he failed in this intention. Cut off from his own culture, he remained an alien in exile who did not quite manage to adapt to his new life." (92)

However, when he heard that his friends in Germany were being arrested and being imprisoned in concentration camps, Grosz once again returned to political themes. In 1934 he produced He was a writer, about the death of Erich Mühsam in Oranienburg Concentration Camp. Another friend, Hans Borchardt, was interned in Dachau Concentration Camp before escaping to America: "The camp seemed to him like some kind of hell where those sharing damnation did not by any means share solidarity. Those strapped up together had become perfectly transparent like gelatine, their screams wrapped round with straw. Altogether things were very quiet there, much quieter than in the real world. Even the sub-machine guns had silencers." (93)

Grosz later wrote: "Many things that in Germany had frozen inside me now began to melt, and in America I discovered once again my delight in painting. Deliberately and with great care I burnt a part of my past... If temporarily I suffered from deep depressions, that had nothing to do with America. It was like some threatening flash of summer lightning, like far-away conflagrations and the smell of blood. I painted these visions of ruins in which the fire was still raging. That was long before the war." (94)

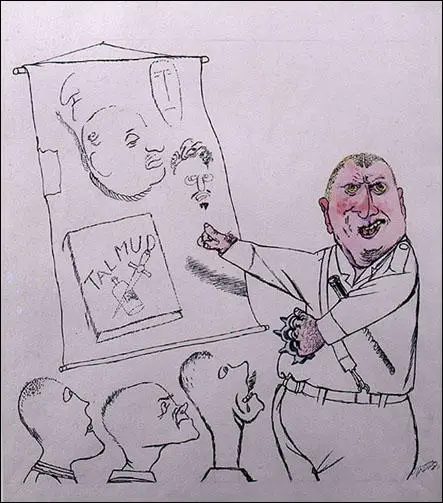

In 1936 a New York publisher brought out a volume of recent Grosz drawings. Several of these dealt with the subjects of the anti-Semitism and anti-Bolshevism of Hitler's government. In one drawing, The Letter to an Anti-Semite (1935), Grosz "shows a teacher demonstrating to his chained pupils a picture of the enemy, a blood-dripping Jewish Bolshevik, while next to it hangs the ideal of the upright German complete with a sword and palm leaf." (95) In 1938 Grosz became an American citizen. (96)

On 27th November, 1936, Joseph Goebbels issued the following decree: "On the express authority of the Führer, I hereby empower the President of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts, Professor Ziegler of Munich, to select and secure for an exhibition works of German degenerate art since 1910, both painting and sculpture, which are now in collections owned by the German Reich, by provinces, and by municipalities. You are requested to give Professor Ziegler your full support during his examination and selection of these works." (97)

It is estimated that 285 of George Grosz's works were confiscated. Other artists who suffered included Emil Nolde (1,052), Erich Heckel (729), Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (688), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (639), Max Beckmann (509), Christian Rohlfs (418), Oskar Kokoschka (417), Lyonel Feininger (378), Ernst Barlach (381), Otto Müller (357), Karl Hofer (313), Max Pechstein (326), Lovis Corinth (295), Otto Dix (260), Franz Marc (130), Paul Klee (102), Paula Modersohn-Becker (70) and Kathe Kollwitz (31). The campaign against "degenerate art" took in work by 1,400 artists in all. (98)

The Exhibition of Degenerate Art opened in Munich on 19th July, 1937. It included 650 works of art confiscated from 32 German museums. The exhibition travelled to twelve other cities from 1937 to 1941. In all, the show drew more than 3 million visitors. The exhibition sought to demonstrate the “degeneration” of artworks by placing them alongside drawings done by the mentally retarded and photographs of the physically handicapped. Grosz's work was placed in a section that were considered to be "art as a tool of Marxist propaganda against military service". It was claimed that in these works "German soldiers were depicted as idiots, sexual degenerates and drunks." (99)

It has been argued that after George Grosz arrived in America, his importance as an artist went into decline. There are several reasons for this. One concerned his "disappointment about the powerlessness of art in the face of politics". With the success of fascism in Germany made "him aware of the futility of his years of political commitment, particularly against German militarism". Secondly, "yet harder still than this defeat was the suffering which Grosz inflicted upon himself, arising from the boundless hatred which both he and others have diagnosed again and again in his works. For years this hatred was the source of his artistic powers of expression." While living in America he began searching for "new creative impulses - a search that was ultimately to prove futile." (100)

His friend Ernst Toller, also escaped to America. However, he committed suicide in his hotel room in New York City on 22nd May, 1939. "Toller had been found by his secretary, hanging from his bathroom door in a Manhattan hotel. It was said that he must have been thinking of suicide for some time, and that he had had several strange conversations with friends concerning the workings of gas stoves and taps. He had long been suffering from depression; everything seemed to be going wrong for him, and since the Loyalist collapse in Spain he had ceased to be his old self." (101)

In 1946 he wrote: "My pictures are witnesses of my inner world, a world which it is hard to photograph, so that my pictures do not compete with the camera or the newsreel. I create my own fearful fairytale world, full of ruins and populated with ugly dwarfs, frightening superhuman creatures and wicked magicians." (102) The following year he was offered a professorship at the Berlin School of Art. He refusing and told a friend he would rather be poor and a failure in America than a failure and poor in Germany. (103)

George Grosz published his memoirs, The Autobiography of George Grosz in 1955. George Grosz returned to Germany in 1959, saying "My American dream turned out to be a soap bubble". A few days later, on 6th July. "after a night out with friends, the inebriated artist slipped on the stairs of his apartment, dying in the hallway from the injuries". (104)

Otto Dix

Otto Dix, the eldest son of Franz Dix (1862-1942), an iron foundry worker, and Louise Amann (1864-1953), a seamstress, was born in Unternhaus, Germany, on 2nd December, 1891. He spent a lot of time with his cousin, Fritz Amann, who was attempting to make a living as an artist. (105)

After attending elementary school he worked locally. In 1906 he started an apprenticeship with painter Carl Senff, and began painting his first landscapes. In 1910 he became a student at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts. To help fund his education, he accepted commissions and painted portraits of local people. (106)

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Dix volunteered for the German Army and was assigned to a field artillery regiment in Dresden. He later recalled why he joined the army: "I had to experience how someone beside me suddenly falls over and is dead and the bullet has hit him squarely. I had to experience that quite directly. I wanted it. I'm therefore not a pacifist at all - or am I? - perhaps I was an inquisitive person. I had to see all that for myself. I'm such a realist, you know, that I have to see everything with my own eyes in order to confirm that it's like that. I have to experience all the ghastly, bottomless depths for life for myself; it's for that reason that I went to war, and for that reason I volunteered." (107)

In the autumn of 1915 Dix was sent to the Western Front where he served as a non-commissioned officer with a machine-gun unit. He was at the Somme during the major allied offensive during the summer of 1916. Dix was wounded several times during the war. On one occasion he nearly died when a shrapnel splinter hit him in the neck. His experiences on the front line had a dramatic impact on his art: "War is so bestial: hunger, lice, mud, those insane noises... I had the feeling, on looking at the pictures from my early years, that I had completely missed one side of reality so far, namely the ugly aspect." (108)

In November 1917 his unit was transferred to the Eastern Front and after Russia negotiated a peace with Germany, Dix returned to France where he took part in the German Spring Offensive. In August of that year he was wounded in the neck. By the end of the war in 1918, Dix had won the Iron Cross (second class) and reached the rank of vice-sergeant-major. He was discharged from service on 22nd December 1918. (109)

After the war Dix developed left-wing views and his paintings and drawings became increasingly political. Like other German artists such as John Heartfield and George Grosz, Dix became what they called "revolutionary pacifists". As Jonathan Jones has pointed out: "It was not at all obvious that a man such as Dix would create some of the defining pacifist images of the 20th century. In 1914 he was a fierce German patriot who joined up enthusiastically. He became a machine gunner and fought at the Battle of the Somme, efficiently mowing down British troops. He won the Iron Cross (second class) and began training to be a pilot. How did this courageous soldier turn into an anti-war artist? To understand that, we need to comprehend that, during the first world war, a radical minority of Germans turned to artistic and political revolution, rather than nationalism. Like the British war poets, Germany's young artists came to hate the war, but unlike the poets, they organised to resist it." (110)

Otto Dix told Maria Wetzel: "As a young man you don't notice at all that you were, after all, badly affected. For years afterwards, at least ten years, I kept getting these dreams, in which I had to crawl through ruined houses, along passages I could hardly get through. Not that painting would have been a release. The reason for doing it is the desire to create. I've got to do it! I've seen that, I can still remember it, I've got to paint it." (111)

It has been argued by Uwe M. Schneede that Otto Dix was one of the founders of modern Verism (the artistic preference of contemporary everyday subject matter instead of the heroic or legendary in art): "From the garish over-emphasised effects of his Dadaist beginnings he came via the study of the art of previous centuries - especially of old German masters and their technique - to his ponderously constructed pictures, precise in every detail, in which the object is kept balanced between an almost aggressive here-and-now and a removal from reality." (112)

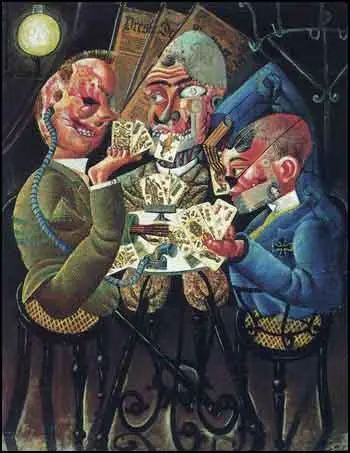

One of his most powerful paintings was The Skat Players (1920). Influenced by the work of John Heartfield, it shows "card-playing cripples... a nightmarish vision of people so mutilated that the scarred remains are scarcely human. Arms, legs, jaws, ears and noses shot away, these men function only as a series of spare parts cobbled together, and their construction is paralleled in the way the picture has been made: it is an elaborate collage, the painted parts combined with glued-on playing-cards, newspapers and bits of wood." (113)

In 1920 George Grosz, John Heartfield and Raoul Hausmann organised the Erste Internationale Dada-Messe in the Berlin gallery owned by Otto Burchard. It was a comprehensive manifestation of Dada (a movement consisted of artists who rejected the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern capitalist society, instead expressing nonsense, irrationality, and anti-bourgeois protest in their works). Among the 174 works in the exhibition were pictures by Dix, Grosz, Heartfield, Hausmann, Max Ernst, Hannah Höch and Rudolf Schlichter. "The text on the panels accompanying each exhibit was partly Dadaist-polemical, partly political." (114)

Dix was angry about the way that the wounded and crippled ex-soldiers were treated in Germany. This was reflected in paintings such as War Cripples (1920), Butcher's Shop (1920) and War Wounded (1922). In October, 1923 Dix's large painting, The Trench, was purchased by the Wallraf-Richartz Museum. The museum's director, Hans F. Secker, assured him that it had been acquired "not without blood and sweat". He added that when the new collection was to be opened to the public in December "your painting will most likely be the greatest sensation." (115)

Walter Schmits, writing in The Kölnische Zeitung, commented: "In the cold, sallow, ghostly light of dawn…a trench appears into which a devastating bombardment has just descended. A poisonous sulphur yellow pool glistens in the depths like a smirk from hell. Otherwise the trench is filled up with hideously mutilated bodies and human fragments. From open skulls brains gush like thick red groats; torn-up limbs, intestines, shreds of uniforms, artillery shells form a vile heap... Half-decayed remains of the fallen, which were probably buried in the walls of the trench out of necessity and were exposed by the exploding shells, mix with the fresh, blood covered corpses. One soldier has been hurled out of the trench and lies above it, impaled on stakes." (116)

When the painting was exhibited in 1924 its depiction of decomposed corpses in a German trench created such a public outcry that the museum's director hid the painting behind a curtain. The local newspaper demanded that the painting should be returned to the artist. Whereas a journalist claimed that the painting had received so much publicity that it had increased the number of people who had seen it. Another critic described it as "perhaps the most powerful as well as well as the most anti-war statements in modern art". In 1925 the then-mayor of Cologne, Konrad Adenauer, cancelled the purchase of the painting and forced Secker to resign. (117)

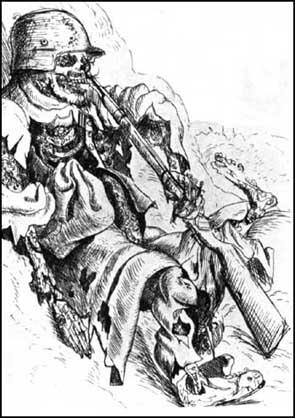

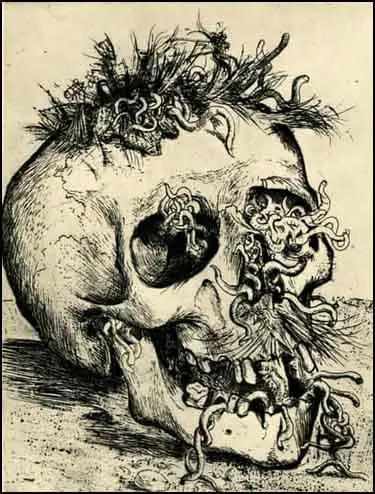

During the First World War, Dix had limited opportunities to paint pictures. However, he did make a large number of sketches. In 1924 Dix joined with other artists who had fought in the First World War to put on a travelling exhibition of paintings called No More War! Dix also produced a book of etchings, The War (1924). Tom Lubbock described the book as "a series of astonished snapshots, each of which might have the motto: I can't believe that I saw this, but I did." (118)

Hilton Kramer, argued that the people who visited the exhibition would have found it a difficult experience: "The total effect of these images of violence, suffering and death is so grim and so powerful that it’s likely to leave more tender-hearted visitors to the exhibition reeling from the experience. Even though we read about similar horrors in the newspapers every day... such graphic depictions of violent death remain far more disturbing than the printed word." (119)

Another critic commented: "A German soldier sits in a trench, resting against its muddy wall. He is smiling, but the grin is empty and hollow-eyed – for his face is a bare skull. He has been dead a while. No one bothered to bury him. His helmet is still on his skull, and his boots reveal a rotting ankle. In another print, a severed skull lies on the earth. Grass has grown on its crown. More grass resembles a moustache under its nose. Out of the eyes, vegetation bursts. Worms crawl sickeningly out of a gaping mouth." (120)

Frank Whitford has argued that the work of artists such as Otto Dix, developed what became known as the New Realism. "They had grown weary of the years of hectic experimentation that had preceded the war and that they were tired of all kinds of art that were highly subjective, metaphysical, esoteric and accessible only to an elite. They wanted to return to subjects that were familiar to everyone, painted in a way which everyone could understand. Some of them were content simply to mirror common experience of mundane things. Others, more politically inspired, preferred to angle the mirror so that the dark side of society was revealed. All of these artists cultivated a painstakingly realistic style which emulated the smooth, anonymous surface of the photograph." (121)

Dix's artist friends such as George Grosz and John Heartfield joined with Paul Levi, Willie Munzenberg, Clara Zetkin, Ernst Toller, Walther Ulbricht, Heinrich Blücher, Julian Marchlewski, Ernst Thälmann, Hermann Duncker, Hugo Eberlein, Paul Frölich, Wilhelm Pieck, Franz Mehring, and Ernest Meyer. to form the German Communist Party (KPD). Over the next few years Grosz and Heartfield produced designs and posters for the organization. (122) Dix had original agreed with them about politics but refused to join the KPD. When a friend asked him to join he replied: "I don't want to hear about your stupid politics - I'd rather spend the 5 marks' membership fee on a whore." (123)

Dix worked for six years on what is considered to be one of his two great masterpieces, Metropolis (1928). It is a triptych (a painting on three panels side by side). With "dazzling colour and great richness of invention, he embodied his vision of Berlin at the height of its frenzied decadence of the 1920s." In the left-hand panel, Dix shows himself as a war cripple entering Berlin and being greeted by a row of beckoning prostitutes. "Bleating saxophones coax customers on to the dance floor. The whores outside tell beggars to get lost and a man with a prosthetic jaw, give a mock salute top passing transvestites." (124)

Dix's experiences in the First World War served to make him particularly sensitive to the hypocrisy of post-war bourgeois society, a hypocrisy which he recognized as the product of mental suppression. "People did not want to see the innumerable war cripples lining the streets, not wishing to be reminded of the disastrous years. People dressed up, donned masks, did anything to avoid being themselves, and lost themselves in the temples of pleasure. Dix created a monument to this society in his Metropolis Triptych, one pushed to extremes through its employment of the sacred form of the triptych." (125)

Otto Dix became preoccupied with the violent excesses of city life in the Weimar Republic. "He came to believe that everyday crime was the reflex to and continuation of the lunacy of war: The catastrophe had began. I drew drunks, people throwing up, men shaking their fists at the moon as they cursed it, the murderers of women, playing at cards while sitting on a create in which the murder victims could be seen... I drew a man looking around him fearfully, washing his hands, which had blood on them." (126)

In 1927 Otto Dix was given a professorship at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts. His interest during this period was focused solely upon people. Only in extremely rare instances were his portraits commissioned works. Instead he embarked on a constant search for personalities who could provide information about their time. He sought models in cafe, in the street, and within his circle of friends who would reflect the changes taking place in society. (127)

Sylvia von Harden, the journalist, recalls how Dix met her in the street: "I must paint you! I simply must! You are representative of an entire epoch! So, you want to paint my lack-luster eyes, my ornate ears, my long nose, my thin lips; you want to paint my long hands, my short legs, my big feet - things which can only scare people off and delight no-one? You have brilliantly characterized yourself, and all that will lead to a portrait representative of an epoch concerned not with the outward beauty of a woman but rather with her psychological condition." (128) The portrait shows von Harden with bobbed hair and monocle, seated at a cafe table with a cigarette in her hand and a cocktail in front of her. (129)

Ernst Friedrich, published his book of photographs of German soldiers who had been badly disfigured by warfare. Dix made extensive use of these photographs when he returned to the subject of war. In 1928 he said: "People were already beginning to forget what horrible suffering the war had brought them." He completed the second of his masterpieces, Trench Warfare in 1932. It was a painting that attempted to drain war of any heroism or nobility. (130)

Trench Warfare, like his other masterpiece, Metropolis (1928) is a triptych. Very popular in medieval times, this form was usually used to make altar-pieces. It has three main panels, with a fourth as a supporting panel or predella below the main central panel. This panel is based on The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb by Hans Holbein.The large central panel is a 204 cm (80 in) square; the flanking panels to either side the same height but half the width, 102 cm (40 in) each; and the predella below the central panel has the same width but is only 60 cm (24 in) high. The left-handed panel shows German soldiers marching off to war, the central panel is a scene of destroyed houses and mangled bodies, and the right-hand panel side panel shows soldiers struggling home from the war. (131)

On 4th January, 1933, Adolf Hitler had a meeting with Franz von Papen and decided to work together for a government. It was decided that Hitler would be Chancellor and Von Papen's associates would hold important ministries. "They also agreed to eliminate Social Democrats, Communists, and Jews from political life. Hitler promised to renounce the socialist part of the program, while Von Papen pledged that he would obtain further subsidies from the industrialists for Hitler's use... On 30th January, 1933, with great reluctance, Von Hindenburg named Hitler as Chancellor." (132)

Most of his artistic friends, including George Grosz and John Heartfield, fled Nazi Germany. As Dix had not been critical of Hitler he thought he would be safe. He justified his non-political stance by the words: "Artists shouldn't try to improve and convert they're far too insignificant for that. They must only bear witness." However, Hitler hated Dix's anti-war paintings and he was sacked as professor at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts. Dix's dismissal letter said that his work "threatened to sap the will of the German people to defend themselves." (133)

Otto Dix continued to paint pictures about the First World War. An example of this was Flanders (1934), a painting that shows a scene from the Western Front. Dix later claimed was Inspired by a passage from Under Fire, a novel written by the French soldier, Henri Barbusse. In the picture dead bodies float in water-filled shell-holes while those soldiers still alive resemble rotting tree stumps. "The central figure, a soldier, shelters behind a tree stump, trying to snatch some sleep before once more going into battle. The landscape is completely obliterated, leaving only destroyed buildings and trees, and water-filled shell craters. All around are dead, wounded or exhausted men, who lie or sit in a morass of mud while the sky appears to bear down on them, dark but for the restricted orange glow of the sun." (134)

On 27th November, 1936, Joseph Goebbels issued the following decree: "On the express authority of the Führer, I hereby empower the President of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts, Professor Ziegler of Munich, to select and secure for an exhibition works of German degenerate art since 1910, both painting and sculpture, which are now in collections owned by the German Reich, by provinces, and by municipalities. You are requested to give Professor Ziegler your full support during his examination and selection of these works." (135)

It is estimated that 260 of Otto Dix's works were confiscated. "He was despised by Hitler not just because he drew and painted in a spiky, gnarled, ghoulish way that decried the ravages of World War I and spoke to Weimar anxiety, but because his art mocked the German idea of heroism. The Munich self-portrait conveys a pride that seems ready to vanquish an enemy that had not quite appeared on the scene when Dix painted the work in 1919 but that both he and his art would outlast." (136)

Other artists who suffered included Emil Nolde (1,052), Erich Heckel (729), Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (688), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (639), Max Beckmann (509), Christian Rohlfs (418), Oskar Kokoschka (417), Lyonel Feininger (378), Ernst Barlach (381), Otto Müller (357), Karl Hofer (313), Max Pechstein (326), Lovis Corinth (295), George Grosz (285), Franz Marc (130), Paul Klee (102), Paula Modersohn-Becker (70) and Kathe Kollwitz (31). The campaign against "degenerate art" took in work by 1,400 artists in all. (137)

The Exhibition of Degenerate Art opened in Munich on 19th July, 1937. It included 650 works of art confiscated from 32 German museums. The exhibition travelled to twelve other cities from 1937 to 1941. In all, the show drew more than 3 million visitors. The exhibition sought to demonstrate the “degeneration” of artworks by placing them alongside drawings done by the mentally retarded and photographs of the physically handicapped. Dix's work was placed in a section that were considered to be "art as a tool of Marxist propaganda against military service". It was claimed that in these works "German soldiers were depicted as idiots, sexual degenerates and drunks." (138)

Dix, like all other artists, was forced to join the Nazi government's Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (Reichskammer der bildenden Kuenste), a subdivision of Goebbels' Cultural Ministry (Reichskulturkammer). Membership was mandatory for all artists in the Reich. Otto Dix had to promise to paint only inoffensive landscapes or portraits. According to one of his biographers, Otto Conzelmann, Dix still painted an occasional allegorical painting that criticized Nazi ideals. (139)

In 1939 Otto Dix was arrested and charged with involvement in a plot on Hitler's life that had taken place in Munich. . However, he was eventually released and the charges were dropped. In the Second World War Dix was conscripted into the Volkssturm (German Home Guard). In 1945 Dix was forced to join the German Army and at the end of the war was captured by the French Army and was put into a prisoner-of-war camp. (140)

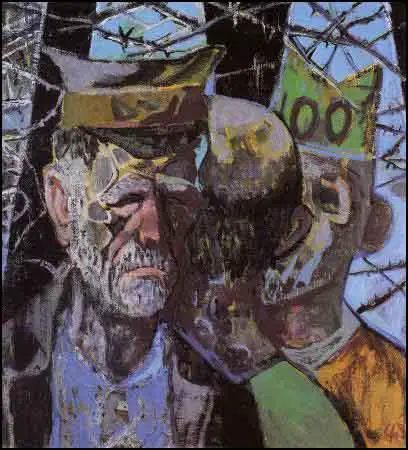

Released in February 1946, Dix returned to Dresden, a city that had been virtually destroyed by heavy bombing. Most of Dix's post-war paintings were religious allegories. However, paintings such as Job (1946), Masks in Ruins (1946) and Ecce Homo II (1948) dealt with the suffering caused by the Second World War. He also painted the anguished Self Portrait as Prisoner of War (1947) in which the barbed wire evokes the crown of thorns of the Crucifixion. (141)

Otto Dix died on 25th July, 1969.

Käthe Kollwitz

Käthe Schmidt, the daughter of Katharina and Karl Schmidt, was born in the industrial city of Königsberg, on 8th July 1867. Her father was a stone mason and house builder, who developed strong socialist opinions after reading the work of Karl Marx. Her mother was the daughter of Julius Rupp, a nonconformist religious leader who suffered much political abuse. (142)

She was a "quiet, shy and nervous" child and spent most of her time with her older siblings, Julie and Konrad: "There were endless places to play and numerous adventures to be had in those yards. For example, a pile of coal had been unloaded from a boat and dumped in the yard in such a way that it sloped up gently and then fell off sharply on the side facing our garden. It was a risky matter to climb up almost to the brink. I myself never dared, but Konrad did. Another boy who tried it was hurt." (143)

Karl Schmidt was educated to become a lawyer but had not followed his profession because his political, social, and moral views made it impossible for him to serve what he considered to be the authoritarian government led by Otto von Bismarck. He joined the Social Democratic Party (SDP). According to Martha Kearns: "Schmidt was a man of the future in his educational as well as political views. Unlike many Prussian fathers... the head of the Schmidt family was not a strict disciplinarian and he did not believe in corporal punishment. A moral idealist, he taught his children to correct their behaviour through self-control, choosing to guide rather than force their development.... In a day when girls were rarely encouraged to aspire to roles other than those of wife and mother, he personally helped to develop the individual talents of each of his three daughters." (144)

Käthe was also influenced by her grandfather who also held strong socialist beliefs and had been imprisoned because his religious views differed from those of Fredrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia. She later recalled: "He was always ready to give, was always kindly and informative, and often laconically humorous... He was tall, thin, dressed in black up to his chin, his eye-glasses having a faintly bluish tinge, his blind eye covered by a somewhat more opaque glass." (145)

Käthe greatly admired her grandfather: "I respected him, but was timid in his presence because I was a bashful child. I did not have the personal relationship with him which my two older sisters and, above all, my brother experienced. Along with the other children of the congregation I had religious instruction under him, an instruction which perhaps passed over the heads of most of the children, myself included. The teaching consisted of religious history, discussion of the gospels, and commentary on the Sunday sermon. A loving God was never brought home to us." (146)

It was very important to Karl Schmidt that his children grew up with a sympathy for the plight of the working-class. Käthe remembers her father reading the poem, The Song of the Shirt, written by the English poet, Thomas Hood. Käthe later explained that as her father "read the last lines, he became so moved that his voice grew fainter and fainter until he was unable to finish. His silent identification with the poor seamstress filled the room. In the silence Käthe, too, experienced the sweat, heat, and grind of a shirt factory and the working woman's numb fatigue." (147)