Education in Nazi Germany

The social historian, Richard Grunberger, has argued in A Social History of the Third Reich (1971) that when Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933 he inherited a very conservative educational system: "The influence of Germany's educational system on her national fortunes invites comparison with that of the playing-fields of Eton on the Battle of Waterloo. It was in the classrooms that the foundations were laid for Bismarck's victories over Danes, Austrians and French abroad and over German parliamentarians at home." (1)

Hitler held very strong opinions on education. The only teacher he liked at secondary school was Leopold Potsch, his history master. Potsch, like many people living in Upper Austria, was a German Nationalist. Potsch told Hitler and his fellow pupils of the German victories over France in 1870 and 1871 and attacked the Austrians for not becoming involved in these triumphs. Otto von Bismarck, the first chancellor of the German Empire, was one of Hitler's early historical heroes. (2)

Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf (1925): "Dr. Leopold Potsch... used our budding nationalistic fanaticism as a means of educating us, frequently appealing to our sense of national honor. By this alone he was able to discipline us little ruffians more easily than would have been possible by any other means. This teacher made history my favorite subject. And indeed, though he had no such intention, it was then that I became a little revolutionary. For who could have studied German history under such a teacher without becoming an enemy of the state which, through its ruling house, exerted so disastrous an influence on the destinies of the nation? And who could retain his loyalty to a dynasty which in past and present betrayed the needs of the German people again and again for shameless private advantage?" (3)

Changes to the School Curriculum

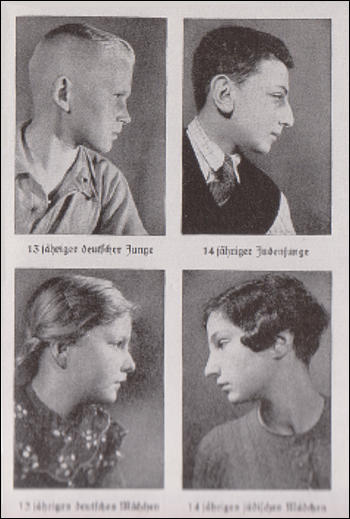

Hitler immediately made changes to the school curriculum. Education in "racial awareness" began at school and children were constantly reminded of their racial duties to the "national community". Biology, along with political education, became compulsory. Children learnt about "worthy" and "unworthy" races, about breeding and hereditary disease. "They measured their heads with tape measures, checked the colour of their eyes and texture of their hair against charts of Aryan or Nordic types, and constructed their own family trees to establish their biological, not historical, ancestry.... They also expanded on the racial inferiority of the Jews". (4)

As Louis L. Snyder has pointed out: "There were to be two basic educational ideas in his ideal state. First, there must be burnt into the heart and brains of youth the sense of race. Second, German youth must be made ready for war, educated for victory or death. The ultimate purpose of education was to fashion citizens conscious of the glory of country and filled with fanatical devotion to the national cause." (5)

The Minister of the Interior, Wilhelm Frick, claimed that the idea that history teaching should be objective was a fallacy of liberalism. (6) "The purpose of history was to teach people that life was always dominated by struggle, that race and blood were central to everything that happened in the past, present and future, and that leadership determined the fate of peoples. Central themes in the new teaching including courage in battle, sacrifice for a greater cause, boundless admiration for the Leader and hatred of Germany's enemies, the Jews." (7)

Hitler appointed the loyal Bernhard Rust as Minister for Education. Rust lost his job as a schoolteacher in 1930 after being accused of having a sexual relationship with a student. He was not charged with the offence because of his "instability of mind". Rust's task was to change the education system so that resistance to fascist ideas were kept to a minimum. (8)

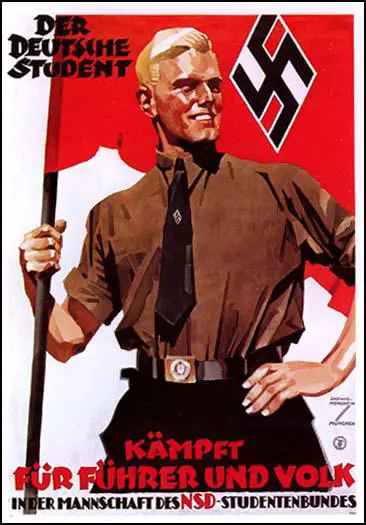

At school the students were taught to worship Adolf Hitler: "As the teacher entered the class, the students would stand and raise their right arms. The teacher would say, For the Führer a triple victory, answered by a chorus of Heil! three times... Every class started with a song. The almighty Führer would be staring at us from his picture on the wall. These uplifting songs were brilliantly written and composed, transporting us into a state of enthusiastic glee." (9)

All school textbooks were withdrawn before new ones were published that reflected the Nazi ideology. Additional teaching materials were issued by Nazi teachers' organizations in different parts of the country. A directive issued in January 1934 made it compulsory for schools to educate their pupils "in the spirit of National Socialism". Children were encouraged to go to school wearing their Hitler Youth and German Girls' League uniforms. School noticeboards were covered in Nazi propaganda posters and teachers often read out articles written by anti-semites such as Julius Streicher. (10)

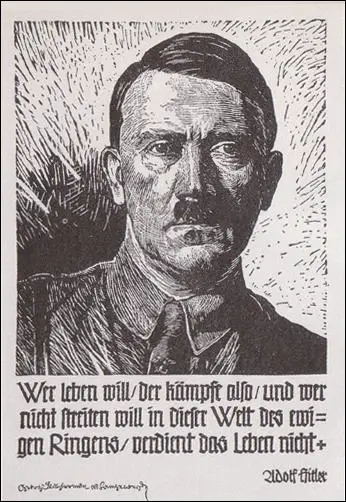

whoever refuses to fight in this world of eternal challenge has no right to live." (c. 1940)

In every schoolbook was an illustration of Hitler with one of his sayings as a frontispiece. Tomi Ungerer claims that his schoolbooks were strewn with pages of sayings from the Führer: "Learn to sacrifice for your fatherland. We shall go onwards. Germany must live. In your race is your strength. You must be true, you must be daring and courageous, and with each other form a great and wonderful comradeship." (11)

Marianne Gärtner went to a private school in Potsdam and noticed a lot of changes after Hitler gained power: "None of my neatly dressed, well-behaved primary-school mates questioned the new books, the new songs, the new syllabus, the new rules or the new standard script, and when - in line with national socialist educational policies - the number of PT periods was increased at the expense of religious instruction or other classes, and competitive field-events added to the curriculum, the less studious and the fast-legged among us were positively delighted." (12)

In his autobiography, A Childhood under the Nazis (1998), Tomi Ungerer commented that one of the textbooks that he was forced to use was the anti-Semitic book, The Jewish Question in Education, which contained guidelines for the "identification" of Jews (13). Written by Fritz Fink, with an introduction by Julius Streicher it included passages such as the "Jews have different noses, ears, lips, chins and different faces than Germans" and "they walk differently, have flat feet... their arms are longer and they speak differently." (14)

Some students began to question the way that Jews were portrayed in the classroom. Inge Scholl, later recalled what happened on a trip with the German League of Girls. "We went on trips with our comrades in the Hitler Youth and took long hikes through our new land, the Swabian Jura.... We attended evening gatherings in our various homes, listened to readings, sang, played games, or worked at handcrafts. They told us that we must dedicate our lives to a great cause.... One night, as we lay under the wide starry sky after a long cycling tour, a friend - a fifteen-year-old girl - said quite suddenly and out of the blue, Everything would be fine, but this thing about the Jews is something I just can't swallow. The troop leader assured us that Hitler knew what he was doing and that for the sake of the greater good we would have to accept certain difficult and incomprehensible things. But the girl was not satisfied with this answer. Others took her side, and suddenly the attitudes in our varying home backgrounds were reflected in the conversation. We spent a restless night in that tent, but afterwards we were just too tired, and the next day was inexpressibly splendid and filled with new experiences." (15)

Teachers in Nazi Germany

In 1933 all Jewish teachers were dismissed from German schools and universities. Bernhard Rust explained the reasons for this decision: " As a consequence of the demand thus clearly formulated by the Nuremberg Laws, Jewish teachers and Jewish pupils have had to quit German schools, and schools of their own have been provided by and for them as far as possible. In this way, the natural race instincts of German boys and girls are preserved; and the young people are made aware of their duty to maintain their racial purity and to bequeath it to succeeding generations. " (16)

On her first day at school Elsbeth Emmerich, a Jewish girl, took her teacher flowers. However, her teacher, Frau Borsig, was not impressed: "Frau Borsig... threw the flowers in the bin... One thing she did like to receive from us was Heil Hitler! Every day we had to greet her, and other grown-ups, with the salute. I was used to doing this, but it still embarrassed me. On my way to school one day I went into a busy shop without making the greeting, thinking no one would notice. But a shop assistant pounced on me, saying angrily, Don't you know the German greeting? She made me walk out and come back into the shop again, using the right greeting. I must have blushed to the roots of my long plaited hair as I held my arm out and said, Heil Hitler! in a pretend grown-up voice. Then she started talking loudly to the other customers about children's bad manners nowadays." (17)

Hans Massaquoi was only seven years old when Hitler came to power. His mother was German but his father was African: "In 1933, my first teacher was fired for political reasons. I don't know what her involvements were. Gradually, the old teachers were replaced with younger ones, those with Nazi orientations. Then I began to notice a change in attitude. Teachers would make snide remarks about my race. One teacher would point me out as an example of the non-Aryan race. One time, I must have been ten, a teacher took me aside and said, When we're finished with the Jews, you're next. He still had some inhibitions. He did not make that announcement before the class. It was a private thing. A touch of sadism." (18)

Teachers who did not support the Nazi Party were sacked. One girl who successfully left Nazi Germany when she was sixteen later wrote: "Teachers had to pretend to be Nazis in order to remain in their posts, and most of the men teachers had families which depended on them. If somebody wanted to be promoted he had to show what a fine Nazi he was, whether he really believed what he was saying or not. In the last two years, it was very difficult for me to accept any teaching at all, because I never knew how much the teacher believed in or not." (19)

Effie Engel, who went to school in Dresden, pointed out: "The progressive teachers in our school all left and we got a number of new teachers. In my last two years of school, we got some teachers who had already been reprimanded. The fascists allowed them to be reinstated if they thought they were no longer compromised by anything else. But I also knew two teachers who never got a job again in the entire Hitler period.... One of the new teachers was in the SA and came to school in his uniform. I couldn't stand him. In part, we couldn't stand him because he was so loud and crude." (20)

It has been estimated that by 1936 over 32 per cent of teachers were members of the Nazi Party. This was a much higher figure than for other professions. Teachers who were members, wore their uniforms in the classroom. The teacher would enter the classroom and welcome the group with a ‘Hitler salute’, shouting "Heil Hitler!" Students would have to respond in the same manner. It has been claimed that before Adolf Hitler took power a large proportion pf teachers were members of the German Social Democratic Party. One of the jokes that circulated in Germany during this period referred to this fact: "What is the shortest measurable unit of time? The time it takes a grade-school teacher to change his political allegiance." (21)

German Education (May 1933)

By 1938 two-thirds of all elementary school teachers were indoctrinated at special camps in a compulsory one-month training course of lectures. What they learned at camp they were expected to pass on to their students. (22) Headmasters were instructed to dismiss teachers who were not supporters of Hitler. However, some anti-Nazi teachers survived: "I am trying through the teaching of geography to do everything in my power to give the boys knowledge and I hope later on, judgment, so that when, as they grow older, the Nazi fever dies down and it again becomes possible to offer some opposition they may be prepared. There are four or five masters who are non-Nazis left in our school now, and we all work on the same plan. If we leave, Nazis will come in and there will be no honest teaching in the whole school. But if I went to America and left others to do it, would that be honest, or are the only honest people those in prison cells? If only there could be some collective action amongst teachers." (23)

Hitler Youth and Education

By 1938 there were 8,000 full-time leaders of the Hitler Youth. There were also 720,000 part-time leaders, often schoolteachers, who had been trained in National Socialist principles. One teacher, who was hostile to Hitler, wrote to a friend: "In the schools it is not the teacher, but the pupils, who exercise authority. Party functionaries train their children to be spies and agent provocateurs. The youth organizations, particularly the Hitler Youth, have been accorded powers of control which enable every boy and girl to exercise authority backed up by threats. Children have been deliberately taken away from parents who refused to acknowledge their belief in National Socialism. The refusal of parents to 'allow their children to join the youth organization' is regarded as an adequate reason for taking the children away." (24)

Teachers constantly feared the possibility that their Hitler Youth students would inform on them. Herbert Lutz went to a school in Cologne. "My favorite teacher was my math teacher. I remember that one day he asked me a question. I was wearing my uniform, and I stood up, clicked my heels, and he blew up." The teacher shouted: "I don't want you to do this. I want you to act like a human being. I don't want machines. You're not a robot." After the lesson he called Lutz into his office and apologized. Lutz later recalled: "He was probably afraid that I might report him to the Gestapo." (25)

For example, a 38-year-old teacher in Düsseldorf told a joke to her class of twelve-year-olds, that was slightly critical of Adolf Hitler. She immediately realised that she had made a mistake and pleaded with the children not to tell anybody about it. One of the children told his parents and they promptly informed the Gestapo. She immediately lost her job and sent to prison for three-weeks. (26)

Tomi Ungerer claims that his teachers encouraged his students to inform on his parents. "We were promised a reward of money if we denounced our parents or our neighbours - what they said or did... We were told: Even if you denounce your parents, and if you should love them, your real father is the Führer, and being his children you will be the chosen ones, the heroes of the future." (27)

Irmgard Paul went to school in Berchtesgaden. "Fräulein Hoffmann, a slender, short woman of indeterminate age, welcomed me and assigned me a seat. After the first morning I knew that she was not the ogre that Fräulein Stöhr had been but that she too was a Nazi fanatic, more dangerous, it turned out, than Stöhr... Monday mornings each pupil had to weigh in with at least two pounds of used paper and a ball of smoothed-out silver aluminum foil to help with the war effort."

One day Irmgard asked her grandfather asked if she could take some of his old journals to school to help Germany win the war. "He looked at me as if he had not quite understood my question and then said in a calm, icy tone that not a sliver bf any of his magazines would go to support the war of that scoundrel Hitler... How dare he not support the war that we were told every day was a life-and-death struggle for the German people? I left the workshop without the journals but what I felt would be a permanent resentment against my grandfather."

Soon afterwards Fräulein Hoffmann invited Irmgard Paul to her home "to have a special treat of hot chocolate and cookies at her house". It was not long before Irmgard discovered why she had been asked to visit her teacher: "After a few polite words she asked point-blank what my grandfather thought about Adolf Hitler and what he said about the war. I was still angry with my grandfather but stalled, sitting uncomfortably on the moss green, upholstered chair in Fräulein Hoffmann's living room, weighing my feelings against my answer. On the one hand, grandfather was withholding paper for the war effort... On the other hand, he was my grandfather. I knew the twinkle in his eyes when he was amused and had seen tears running down his face when one after another the messages arrived that both his apprentices had been killed on the eastern front... After much too long a pause I came to the decision that I liked this nosy teacher less than my grandfather."

Irmgard Paul commented in her autobiography, On Hitler's Mountain: My Nazi Childhood (2005): "Although I did not know it that day, Fräulein Hoffmann was a Nazi informer, and my telling the truth would have sent grandfather to a concentration camp. Something had made me protect my grandfather, but it took a long time before I realized how lucky I (and he) had been in making that decision. On that particular day, though, I felt thoroughly sick of these conflicts forced on me by adults." (28)

Hildegard Koch was a member of the League of German Girls (BDM), the female branch of the Hitler Youth movement. She later recalled how the students controlled the curriculum: "As time went on more and more girls joined the BDM, which gave us a great advantage at school. The mistresses were mostly pretty old and stuffy. They wanted us to do scripture and, of course, we refused. Our leaders had told us that no one could be forced to listen to a lot of immoral stories about Jews, and so we made a row and behaved so badly during scripture classes that the teacher was glad in the end to let us out." (29)

Erich Dressler played an active role in getting rid of teachers he considered not to be supporters of the Nazi Party: "In 1934, when I had reached the age of ten, I was sent to the Paulsen Realgymnasium. This was still a regular old-fashioned place with masters in long beards who were completely out of sympathy with the new era. Again and again we noticed that they had little understanding for the Führer's maxim - the training of character comes before the training of intellect.They still expected us to know as much as the pupils used to under the Jewish Weimar Republic, and they pestered us with all sorts of Latin and Greek nonsense instead of teaching us things that might be useful later on. This brought about an absurd state of affairs in which we, the boys, had to instruct our masters. Already we were set aflame by the idea of the New Germany, and were resolved not to be influenced by their outdated ideas and theories, and flatly told our masters so. Of course they said nothing, because I think they were a bit afraid of us, but they didn't do anything about changing their methods of teaching."

It was decided to get rid of the Latin teacher. "Our Latin master set us an interminable extract from Caesar for translation. We just did not do it, and excused ourselves by saying that we had been on duty for the Hitler Youth during the afternoon. Once one of the old birds got up courage to say something in protest. This was immediately reported to our Group Leader who went off to see the headmaster and got the master dismissed. He was only sixteen, but as a leader in the Hider Youth he could not allow such obstructionism to hinder us in the performance of duties which were much more important than our school work.... Gradually the new ideas permeated the whole of our school. A few young masters arrived who understood us and who themselves were ardent national socialists. And they taught us subjects into which the national revolution had infused a new spirit. One of them took us for history; another for racial theory and sport. Previously we had been pestered with the old Romans and such like; but now we learned to see things with different eyes. I had never thought much about being well educated; but a German man must know something about the history of his own people so as to avoid repeating the mistakes made by former generations." (30)

Teachers encouraged members of the Hitler Youth to inform on their parents. For example, they set essays entitled "What does your family talk about at home?" According to one source: "Parents... were alarmed by the gradual brutalisation of manners, impoverishment of vocabulary and rejection of traditional values... Their children became strangers, contemptuous of monarchy or religion, and perpetually barking and shouting like pint-sized Prussian sergeant-majors." (31)

Ilse Koehn started high school in 1939. She found that the young teachers were strong supporters of Adolf Hitler. "Dr. Lauenstein was the only male teacher. Young and tall, handsome too, he was quite a contrast to the ladies, who were all in their fifties. He alone wore the Nazi Party button, shouted Heil Hitler when he entered the classroom and spent the next fifteen minutes expounding on the Führer's Blood and Soil philosophy. Old German soil soaked with German blood, as he put it. He was unbearably bombastic when he talked about the superior Aryan race. When he finally turned to Goethe, there was always a sigh of relief. No one, certainly not I, had any idea what he had been talking about." (32)

Irmgard Paul first went to her Berchtesgaden school in April 1940. "From the day mother delivered me into Fräulein Stöhr's clutches it was obvious that this woman was a fanatical Nazi. A true believer. Surely she had become a teacher not because she had an affinity for children but because she wanted to tyrannize them. The Nazi doctrines designed to raise citizens wholly obedient to the Führer's bidding captivated and excited her... The war had already eaten into resources and materials, as well as the supply of male teachers, most of whom were drafted. As a result, Fräulein Stöhr got to sink her fangs into one hundred children belonging to three different grades. We were huddled together in her stark, whitewashed classroom learning the basics by rote plus a bit of local history, needlework for the girls, and geography."

Her father was killed in France on 5th July, 1941. "People in Berchtesgaden reacted in two different ways to his death - our friends, relatives, and neighbours, with sadness and compassion; the Nazi officials in our lives with pompous, irrelevant condolences. My father's boss, Herr Adler, who for unknown reasons was not drafted, came by - in his S.A. uniform, no less - a few days after the news arrived and said in an oily voice to my stricken mother, Chin up, Frau Paul, chin up. He died for the Führer."

"The morning after we got the death notice, my teacher, Fräulein Stöhr, a fanatical Nazi, ordered me to stand up in front of the class and tell everyone how proud I was that my father had given his life for the Führer. I stood before those hundred children, my face burning, my hurt heart thumping. I clenched my fists and swallowed hard, determined not to cry or otherwise show anyone how I felt. I forced myself to drain all emotion from my voice, even forcing my mouth into a grin, and said, Yes, we heard yesterday that my father died in France for the Führer. Heil Hitler. My face was flushed, but I made sure to walk calmly back to my seat." (33)

According to one report the activities of the Hitler Youth and the Nazi government was slowly destroying the education system in Germany. "Everything that has been built up over a century of work by the teaching profession is no longer there in essence... They have been wilfully destroyed from above. No thought any more of proper working methods in school, or of the freedom of teaching. In their place we have cramming and beating schools, prescribed methods of learning and... learning materials. Instead of freedom of learning, we have the most narrow-minded school supervision and spying on teachers and pupils. No free speech is permitted for teachers and pupils, no inner, personal empathy. The whole thing has been taken over by the military spirit." (34)

School Textbooks

New mathematic textbooks were introduced and included "social arithmetic", which "involved calculations designed to achieve a subliminal indoctrination in key areas - for example, sums requiring the children to calculate how much it would cost the state to keep a mentally ill person alive in an asylum." (35) Other questions used in mathematics revolved around artillery trajectories and fighter-to-bomber ratios. This was a typical question from a mathematics text: "An airplane flies at the rate of 240 kilometers per hour to a place at a distance of 210 kilometers in order to drop bombs. When may it be expected to return if the dropping of bombs takes 7.5 minutes?" (36)

Geography textbooks were produced that "propagated concepts such as living-space and blood and soil, and purveyed the myth of Germanic racial superiority". (37) Biology textbooks emphasized Hitler's views on race and heredity. One popular textbook used had been written by Hermann Gauch: "The animal world can be classified into Nordic men and lower animals. We are thus able to establish the following principle: there exist no physical or psychological characteristics which would justify a differentiation of mankind from the animal world. The only differences that exist are those between Nordic men, on the one hand, and animals... including non-Nordic men." (38)

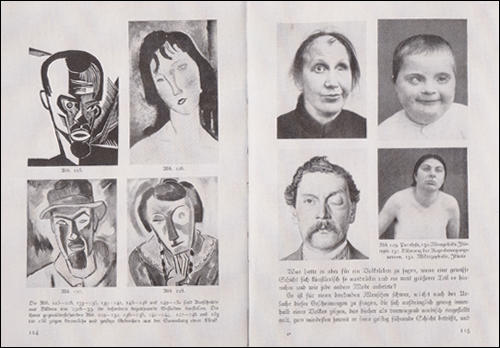

Art was Tomi Ungerer favourite subject. His teacher praised him for his work and he was told: "The Führer needs artists - he himself is one." The government had taken complete control of the art world. "Under the Nazis, painters and sculptors were paid a monthly salary from the state." Textbooks used in the classroom were very hostile to modern art, something that was considered to be degenerate. Below is a school textbook that provides a comparative study between modern paintings and deformed humans. For example, the Amedeo Modigliani (plate 126) is compared to a person with Down's Syndrome. (39)

At school Irmgard Paul was brainwashed into accepting Nazi views on the Jewish race. "We used a book with page after page showing the physical differences between Jews and Germans in grotesque drawings of Jewish noses, lips, and eyes. The book encouraged every child to note these differences and to bring anyone who bore Jewish features on the attention of our parents or teachers. I was horrified by the crimes Jewish people were being accused of - killing babies, loan-sharking, basic dishonesty, and conspiring to destroy Germany and rule the world. The description of the Jewish people would convince any child that these were monsters, not people with sorrows and joys like ours." (40)

Nazi Elite Schools

Bernhard Rust introduced a Nazi National Curriculum. Considerable emphasis was placed on physical training. Boxing was made compulsory in upper schools and PT became an examination subject for grammar-school entry as well as for the school-leaving certificate. Persistently unsatisfactory performance at PT constituted grounds for expulsion from school and for debarment from further studies. In 1936 timetable allocation of PT periods was increased from two to three. Two years later it was increased to five periods. All teachers below the age of fifty were pressed into compulsory PT courses. (41)

Rust also establishment of élite schools called Nationalpolitische Erziehungsanstalten (Napolas). Selection for entry included racial origins, physical fitness and membership of the Hitler Youth. These schools, run by the Schutzstaffel (SS), had the task of training the next generation of high-ranking people in the Nazi Party and the German Army. (42) The syllabus was that of ordinary grammar schools with political inculcation in place of religious instruction and a tremendous emphasis on such sports as boxing, war games, rowing, sailing, gliding, shooting and riding motor-cycles. Only two out of the thirty-nine Napolas constructed over the next few years catered for girls. (43)

After leaving school at the age of eighteen students joined the German Labour Service where they worked for the government for six months. (44) Some young people then went on to university. Bernhard Rust claimed that the new education system would benefit the children of the working-class that made up 45 per cent of Germany's population. This promise was never fulfilled and after six years in office, only 3 per cent of university students came from working-class backgrounds. This was the same percentage as it was before Adolf Hitler came to power. (45)

Women's Education

One of the objectives of the Nazi government was to reduce the number of women in higher education. On 12th January 1934, Wilhelm Frick ordered that the proportion of female grammar school graduates allowed to proceed to university should be no more than 10 per cent of that of the male graduates. (46) That year, out of 10,000 girls who passed the Abitur entry examinations, only 1,500 were granted university admission. In the year before the Nazis came to power there were 18,315 women students in Germany's universities. Six years later this number had fallen to 5,447. The government also ordered a reduction in women teachers. By 1935 the number of women teachers at girls' secondary schools had decreased by 15 per cent. (47)

Gertrud Scholtz-Klink was placed in charge of the Nazi Mother Service. The organization issued a statement explaining its role in Nazi Germany: "The purpose of the National Mother Service is political schooling. Political schooling for the woman is not a transmission of political knowledge, nor the learning of Party programs. Rather, political schooling is shaping to a certain attitude, an attitude that out of inner necessity affirms the measures of the State, takes them into women's life, carries them out and causes them to grow and be further transmitted."

Joseph Goebbels pointed out in a speech in 1934: "Women has the task of being beautiful and bringing children into the world, and this is by no means as coarse and old-fashioned as one might think. The female bird preens herself for her mate and hatches her eggs for him. In exchange, the mate takes care of gathering the food and stands guard and wards off the enemy. Hope for as many children as possible! Your duty is to produce at least four offspring in order to ensure the future of the national stock." (48)

As Richard Evans, the author of The Third Reich in Power (2005) has pointed out: "The reorganization of German secondary schools ordered in 1937 abolished grammar-school education for girls altogether. Girls were banned from learning Latin, a requirement for university entrance, and the Education Ministry did its best instead to steer them into domestic education, for which a whole type of girls school existed... The number of female students in higher education fell from just over 17,000 in 1932-33 to well under 6,000 in 1939." (49)

Problems in Education

One of the major problems for schools in Nazi Germany was attendance. School authorities were instructed to grant pupils leave of absence to enable them to attend Hitler Youth courses. In one study of a school in Westphalia with 870 pupils showed that 23,000 school days were lost because of extra-mural activities during one academic year. This eventually had an impact on educational achievement. On 16th January, 1937, Colonel Hilpert of the German Army complained in Frankfurter Zeitung, that: "Our youth starts off with perfectly correct principles in the physical sphere of education, but frequently refuses to extend this to the mental sphere... Many of the candidates applying for commissions display a simply inconceivable lack of elementary knowledge." (50)

By 1938 it was reported that there was a problem recruiting teachers. It was claimed that one teaching post in twelve was unfilled and Germany had 17,000 less teachers than it had before Adolf Hitler came to power. The main reason for this was the fall in teacher's pay. Entrants to the profession were offered a starting salary of 2,000 marks per annum. After deductions, this worked out at approximately 140 marks per month, or twenty marks more than was earned by the average lower-paid worker. The government tried to overcome this problem by introducing low-paid unqualified auxiliaries into schools. (51)

Second World War

Tomi Ungerer has pointed out that after the outbreak of the Second World War the first hour of school was dedicated to history, especially to the rise of the Nazi movement and the latest news of military victories. "We had a special copybook for this. Indoctrination was daily and systematic. Jazz, modern art, and comic strips were considered degenerate and forbidden. I could easily imagine Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, or Superman and their likes dutifully arrested by the Gestapo to serve in some hard labour squad... We had special classes building model airplanes (to make us future pilots in the Luftwaffe, of course." (52)

The first thing that Tomi Ungerer had to write in his copybook had to be memorized: "Our Führer is named Adolf Hitler. He was born the 20th of April 1889 in Braunau. Our Führer is a great soldier and tireless worker. He delivered German from misery. Now everyone has work, bread, and joy. Our Führer loves children and animals." His first homework was to draw the swastika flag and copy out the following quote from Hitler: "In the swastika lies the mission to fight for the victory of the Aryan race, as well as the triumph of the concept of creative labour, which always, in itself, was anti-Semitic, and always will be." (53)

Primary Sources

(1) Herman Rauschning, Hitler Speaks (1939)

In my great educative work," said Hitler, " I am beginning with the young. We older ones are used up. Yes, we are old already. We are rotten to the marrow. We have no unrestrained instincts left. We are cowardly and sentimental. We are bearing the burden of a humiliating past, and have in our blood the dull recollection of serfdom and servility. But my magnificent youngsters! Are there finer ones anywhere in the world? Look at these young men and boys! What material! With them I can make a new world.

"My teaching is hard. Weakness has to be knocked out of them. In my Ordensburgen a youth will grow up before which the world will shrink back. A violently active dominating, intrepid, brutal youth - that is what I am after". Youth must be all those things. It must be indifferent to pain. There must be no weakness or tenderness in it. I want to see once more in its eyes the gleam of pride and independence of the beast of prey. Strong and handsome must my young men be. I will have them fully trained in all physical exercises. I intend to have an athletic youth - that is the first and the chief thing. In this way I shall eradicate the thousands of years of human domestication. Then I shall have in front of me the pure and noble natural material. With that I can create the new order.

"I will have no intellectual training. Knowledge is ruin to my young men. I would have them learn only what takes their fancy. But one thing they must learn - self-command! They shall learn to overcome the fear of death, under the severest tests. That is the intrepid and heroic stage of youth. Out of it comes the stage of the free man, the man who is the substance and essence of the world, the creative man, the god-man. In my Ordensburgen there will stand as a statue for worship the figure of the magnificent, self-ordaining god-man; it will prepare the young men for their coming period of ripe manhood."

(2) Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (1925)

The whole organization of education, and training which the People's State is to build up must take as its crowning task the work of instilling into the hearts and brains of the youth entrusted to it the racial instinct and understanding of the racial idea. No boy or girl must leave school without having attained a clear insight into the meaning of racial purity and the importance of maintaining the racial blood unadulterated. Thus the first indispensable condition for the preservation of our race will have been established and thus the future cultural progress of our people will be assured.

A reform of particular importance is that which ought to take place in the present methods of teaching history. Scarcely any other people are made to study as much of history as the Germans, and scarcely any other people make such a bad

use of their historical knowledge. If politics means history in the making, then our way of teaching history stands condemned by the way we have conducted our politics. But there would be no point in bewailing the lamentable results of our political conduct unless one is now determined to give our people a better political education. In 99 out of 100 cases the results of our present teaching of history are deplorable. Usually only a few dates, years of birth and names, remain in the memory, while a knowledge of the main and clearly defined lines of historical development is completely lacking. The essential features which are of real significance are not taught. It is left to the more or less bright intelligence of the individual to discover the inner motivating urge amid the mass of dates and chronological succession of events.

The subject matter of our historical teaching must be curtailed. The chief value of that teaching is to make the principal lines of historical development understood. The more our historical teaching is limited to this task, the more we may hope that it will turn out subsequently to be of advantage to the individual and, through the individual, to the community as a whole. For history must not be studied merely with a view to knowing what happened in the past but as a guide for the future, and to teach us what policy would be the best to follow for the preservation of our own people.

(3) Bernhard Rust, Education in the Third Reich (1938)

The systematic reform of Germany's education system was started immediately after the coming into power of National Socialism. If these far-reaching changes were to materialize, teachers had first to be made capable of introducing them. Numerous courses, camps and working communities have been arranged to provide the necessary instruction, which includes the teaching of the philosophy of National Socialism in addition to the strictly educational subjects.

(4) Richard Grunberger, A Social History of the Third Reich (1971)

The influence of Germany's educational system on her national fortunes invites comparison with that of the playing-fields of Eton on the Battle of Waterloo. It was in the classrooms that the foundations were laid for Bismarck's victories over Danes, Austrians and French abroad and over German parliamentarians at home. It could be said of the teachers that they had travaille pour le roi de Prusse both in the metaphorical and the purely literal sense of the phrase: they earned meagre salaries and inculcated an ethos of Prusso-German patriotism.

This they largely contrived to do even when the Empire had followed the Kingdom of Prussia into the limbo of history. Though after 1918 some (mainly elementary) teachers supported the Social Democrats or middle-of-the-road political parties, the schools in general acted as incubators of nationalism under the Weimar Republic. The choice of Hans Grimm's Volk ohne Raum (People without Space) as a standard matriculation text reflected a virtually nation-wide consensus among teachers of German language and literature, while schoolboys would inject new topicality and frisson into the game of Cowboys and Indians by calling it "Aryans and Jews"; by 1931 Jewish communal newspapers were publishing lists of schools where children suffered less exposure to anti-Semitism so that parents could arrange transfers....

Denunciation also constituted an ever-present occupational hazard for teachers, since low marks or adverse comments on essays lifted verbatim from articles in the Nazi Press could be construed as evidence of political opposition. In actual fact, however, the teaching profession represented one of the most politically reliable sections of the population. Ninety-seven per cent of all teachers were enrolled in the Nazi Teachers' Association (the Nationalsozialistische Lehrerbund or NSLB), and as early as 1936 (i.e. before the moratorium on Party recruitment after the seizure of power was lifted) 32 per cent of all NSLB members belonged to the Nazi Party; this incidence of Party membership was nearly twice as high as that found among the Nazi Civil Servants' Association .

Fourteen per cent of teachers compared to 6 per cent of civil servants belonged to the Party's political leadership corps. This remarkable commitment to the regime was exemplified in the highest ranks of the Party hierarchy by seventy-eight District Leaders and seven Gauleiter (and deputy Gauleiter) who had graduated from the teaching profession. It also found expression in the schoolmasterly, moralizing tone which - as we have noted elsewhere - informed so many Nazi utterances. The Party image also benefited from the presence of many teachers at the grass-roots level of its organization, where they acted as "notabilities" (Respektspersonen), masking the more disreputable elements entrenched in the local apparatus.

(5) Baldur von Schirach, head of the Hitler Youth, wrote a prayer that had to be said by school children before meals.

Fuehrer, my Fuehrer given me by God,

Protect and preserve my life for long.

You rescued Germany from its deepest need.

I thank you for my daily bread.

Stay for a long time with me, leave me not.

Fuehrer, my Fuehrer, my faith, my light

Hail my Fuehrer.

(6) One of the books used to study racial science in Nazi Germany was Heredity and Racial Biology for Students by Jakob Graf.

The Aryans (Nordic people) were tall, light-skinned, light-eyed, blond people. The Goths, Franks, Vandals, and Normans, too, were peoples of Nordic blood.

It was Nordic energy and boldness that were responsible for the power and prestige enjoyed by small nations such as the Netherlands and Sweden. Everywhere Nordic creative power has built up mighty empires with high-minded ideas, and to this very day Aryan languages and cultural values are spread over a large part of the world.

(7) Peter Neumann, Other Men's Graves: Diary Of An SS Man (1958)

When Klauss got back from school at five o'clock he bullied me into helping him with his homework. Glancing through his school books, I noticed again how different they are from those I had had only a few years ago. The change has been particularly marked since Streicher became head of his Institute of Political Instruction at Berlin University.

Here is a maths problem, picked out at random: "A Sturmkampfflieger on take-off carries twelve dozen bombs, each weighing ten kilos. The aircraft makes for Warsaw, the centre of international Jewry. It bombs the town. On takeoff with all bombs on board and a fuel tank containing 1,500 kiios of fuel, the aircraft weighed about eight tons. When it returns from the crusade, there are still 250 kilos of fuel left. What is the weight of the aircraft when empty?"

Here is another one I had to solve for Klauss: "The iniquitous Treaty of Versailles, imposed by the French and the English, enabled international plutocracy to steal Germany's colonies. France herself acquired part of Togoland. If German Togoland, temporarily under the administration of the French imperialists, covers fifty-six million square kilometres, and contains a population of eight hundred thousand people, estimate the average living space per inhabitant."

(8) Bernhard Rust, National Socialist Germany and the Pursuit of Learning (1936)

There is, indeed, twofold evidence to show that something was wrong with education. In the first place, the high level of popular enlightenment had failed to protect the German people against the poisonous effects of Marxist teaching and other false doctrines. Large masses of people had fallen victims to them, whilst other sections - more especially those of higher education - had been unable to take up an effective stand against the spread of the poison. If they had, the events of 1918 and the succeeding period of national disintegration and deterioration would have been prevented.

In the second place, a careful study of the situation shows that the German people are sound to the core and are gifted with just as much national sentiment as any other. Hence, the temporary lowering of their previous high standards could not have been the result of any innate inferiority, but the reason must be sought in a faulty system of education, which - notwithstanding its high intellectual achievements - tended to impair the healthy spirit of the nation, men's energies and their soundness of judgment, and to produce selfishness and a deficient sense of national solidarity.

The attainment of high intellectual standards will certainly continue to be urged upon the young people; but they will be taught at the same time that their achievements must be of benefit to the national community to which they belong. As a consequence of the demand thus clearly formulated by the Nuremberg Laws, Jewish teachers and Jewish pupils have had to quit German schools, and schools of their own have been provided by and for them as far as possible. In this way, the natural race instincts of German boys and girls are preserved; and the young people are made aware of their duty to maintain their racial purity and to bequeath it to succeeding generations. As the mere teaching of these principles is not enough, it is constantly supplemented, in the National Socialist State, by opportunities for what may be called "community life". By this term we mean school journeys, school camps, school "homes" in rural neighbourhoods, and similar applications of the corporate principle to the life of schools and scholars.

History insists that every biological race deterioration coincides with the growth of big towns, that these latter exercise a paralysing effect upon community life, and that a nation's strength is rooted in its rural elements. Our National Socialist system of education pays due regard to these important considerations, and makes every effort, to take the young people from the towns to the country, whilst impressing upon them the inseparable connection between racial strength and a healthy open-air life.

(9) Students also studied racial science at university. One of the most popular textbooks used at university to study the subject was a Short Ethnology of the German People by Hans Gunther, the professor of racial science at the University of Jena.

The Nordic race is tall, long-legged, slim, with average height, among males, of about 1.74. The face is narrow, with a rather narrow forehead, a narrow, high-built nose, and a narrow lower jaw and prominent chin. The hair colour is blond.

The relatively great number of Nordic people among the famous and outstanding men and women of all Western countries is striking, as also is the relatively low number of famous men and women without noticeable Nordic strain.

(10) Dr. Schuster, geography teacher, writing in 1938.

I am trying through the teaching of geography to do everything in my power to give the boys knowledge and I hope later on, judgment, so that when, as they grow older, the Nazi fever dies down and it again becomes possible to offer some opposition they may be prepared. There are four or five masters who are non-Nazis left in our school now, and we all work on the same plan. If we leave, Nazis will come in and there will be no honest teaching in the whole school. But if I went to America and left others to do it, would that be honest, or are the only honest people those in prison cells? If only there could be some collective action amongst teachers. But we cannot meet in conference, we cannot have a newspaper.

(11) Milton Mayer, an American journalist, interviewed teachers in Germany for his book, They Thought They Were Free (1955)

"I might have got by without joining," he said more than once. "I don't know. I might have taken my chances. Others did, I mean other teachers in the high school."

"How many?"

"Let me see. We had thirty-five teachers. Only four, well, five, were fully convinced Nazis. But, of these five, one could be argued with openly, in the teachers' conference room; and only one was a real fanatic, who might denounce a colleague to the authorities."

"Did he?"

"There was never any evidence that he did, but we had to be careful around him."

"How many of the thirty-five never joined the Party?"

"Five, but not all for the same reason. Three of the five were very religious. The teachers were all Protestants, of course, but only half a dozen, at most, were really religious these were all anti-Nazi, these half-dozen, but only three of them held out. One of the three was the history teacher (now the director of the school), very nationalistic, very Prussian, but a strong churchman. He stood near the anti-Nazi Confessional Church, but he couldn't join it, of course, or he'd have lost his job. Then there was the theology teacher, who also taught modern languages; he was the best teacher in the school; apart from his religious opposition, his knowledge of-foreign cultures made him anti-Nazi. The third was the mathematics teacher, absolutely unworldly but profoundly pietistic, a member of the Moravian sect."

"And the two who were non-religious and didn't join?"

"One was a historian. He was not an atheist, you understand, just a historian. He was a non-joiner, of anything. He was nonpolitical. He was strongly critical of Nazism, but always on a detached, theoretical basis. Nobody bothered him; nobody paid any attention to him. And vice versa The other nonbeliever was really the truest believer of them all. He was a biologist and a rebel against a religious background. He had no trouble perverting Darwin's 'survival of the fittest' into Nazi racism - he was the only teacher in the whole school who believed it."

"Why didn't he join the Party?"

"He hated the local Kreisleiter the County Leader of the Party, whose father had been a theologian and who himself never left the Church The hatred was mutual. That's why the biologist never joined. Now he's an anti-Nazi.''

(12) Hans Massaquoi was born in Germany in 1926. His mother was German but his father came from Africa. Studs Terkel interviewed Massaquoi about his experiences during Nazi Germany for his book, The Good War (1985)

In 1932, when I started school, I was six years old. In 1933, my first teacher was fired for political reasons. I don't know what her involvements were. Gradually, the old teachers were replaced with younger ones, those with Nazi orientations. Then I began to notice a change in attitude. Teachers would make snide remarks about my race. One teacher would point me out as an example of the non-Aryan race. One time, I must have been ten, a teacher took me aside and said, "When we're finished with the Jews, you're next." He still had some inhibitions. He did not make that announcement before the class. It was a private thing. A touch of sadism.

There was a drive to enroll young kids into the Hitler Youth movement. I wanted to join, of course. My mother took me aside and said, "Look, Hans, you may not understand, but they don't want you." I couldn't understand. All my friends had these black shorts and brown shirts and a swastika and a little dagger which said Blood and Honor. I wanted it just like everybody else. I wanted to belong. These were my schoolmates.

In 1936, our class had a chance to go to Berlin to watch the Olympics. Not all Germans were sold on this Hitler nonsense. Jesse Owens was the undisputed hero of the German people. He was the darling of the 1936 Olympic games. With the exception of a small Nazi elite, they opened their hearts to this black man who ran his butt off. I was so proud, sitting there.

It's clear to me that had the Nazi leadership known of my existence, I would have ended in a gas oven or at Auschwitz. What saved me was there was no black population in Germany. There was no apparatus set up to catch blacks. The apparatus that was set up to apprehend Jews entailed questionnaires that were mailed to all German households. The question was: Jewish or non-Jewish? I could always, without perjuring myself, write: non-Jewish.

(13) Schoolteacher, letter to a friend (December, 1938)

In the schools it is not the teacher, but the pupils, who exercise authority. Party functionaries train their children to be spies and agent provocateurs. The youth organizations, particularly the Hitler Youth, have been accorded powers of control which enable every boy and girl to exercise authority backed up by threats. Children have been deliberately taken away from parents who refused to acknowledge their belief in National Socialism. The refusal of parents to "allow their children to join the youth organization" is regarded as an adequate reason for taking the children away.

(14) Angriff (27th October, 1939)

All subjects - German Language, History, Geography Chemistry and Mathematics - must concentrate on military subjects - the glorification of military service and of German heroes and leaders and the strength of a regenerated Germany. Chemistry will inculcate a knowledge of chemical warfare, explosives. Buna, etc., while mathematics will help the young to understand artillery calculations, ballistics etc.

(15) Erich Dressler, Nine Lives Under the Nazis (2011)

In 1934, when I had reached the age of ten, I was sent to the Paulsen Realgymnasium. This was still a regular old-fashioned place with masters in long beards who were completely out of sympathy with the new era. Again and again we noticed that they had little understanding for the Führer's maxim - the training of character comes before the training of intellect.They still expected us to know as much as the pupils used to under the Jewish Weimar Republic, and they pestered us with all sorts of Latin and Greek nonsense instead of teaching us things that might be useful later on.

This brought about an absurd state of affairs in which we, the boys, had to instruct our masters. Already we were set aflame by the idea of the New Germany, and were resolved not to be influenced by their outdated ideas and theories, and flatly told our masters so. Of course they said nothing, because I think they were a bit afraid of us, but they didn't do anything about changing their methods of teaching. We were thus forced to "defend" ourselves.

This was rather simple. Our Latin master set us an interminable extract from Caesar for translation.We just did not do it, and excused ourselves by saying that we had been on duty for the Hitler Youth during the afternoon. Once one of the old birds got up courage to say something in protest. This was immediately reported to our Group Leader who went off to see the headmaster and got the master dismissed. He was only sixteen, but as a leader in the Hider Youth he could not allow such obstructionism to hinder us in the performance of duties which were much more important than our school work. From that day onwards the question of homework was settled. Whenever we did not want to do it we were simply "on duty," and no one dared to say any more about it.

Gradually the new ideas permeated the whole of our school. A few young masters arrived who understood us and who themselves were ardent national socialists. And they taught us subjects into which the national revolution had infused a new spirit. One of them took us for history; another for racial theory and sport. Previously we had been pestered with the old Romans and such like; but now we learned to see things with different eyes. I had never thought much about being "well educated"; but a German man must know something about the history of his own people so as to avoid repeating the mistakes made by former generations.

Gradually, one after the other of the old masters was weeded out.The new masters who replaced them were young men loyal to the Führer. The new spirit had come to stay.We obeyed orders and we acknowledged the leadership principle, because we wanted to and because we liked it. Discipline is necessary, and young men must learn to obey.

(16) Irmgard Paul, On Hitler's Mountain: My Nazi Childhood (2005)

School was the serious side of life, never meant to make a child happy. From the day mother delivered me into Fräulein Stöhr's clutches it was obvious that this woman was a fanatical Nazi. A true believer. Surely she had become a teacher not because she had an affinity for children but because she wanted to tyrannize them. The Nazi doctrines designed to raise citizens wholly obedient to the Führer's bidding captivated and excited her. I began first grade at Easter 1940, but since Hitler changed the beginning of the school year to the fall shortly afterward, I am not quite sure whether my first year was very short or very long. At any rate, the war had already eaten into resources and materials, as well as the supply of male teachers, most of whom were drafted. As a result, Fräulein Stöhr got to sink her fangs into one hundred children belonging to three different grades. We were huddled together in her stark, whitewashed classroom learning the basics by rote plus a bit of local history, needlework for the girls, and geography.The curriculum did not include anything like "political education", but Fräulein Stöhr knew how to use occasions like my father's death, Hitler's birthday, good or bad news from the front, or the visit of a prominent local Nazi to indoctrinate us.... Hitler found the brown eyes and dark hair dominant among the valley's people not to his liking, suspecting undesirable Italian or even Slavic influences, and accordingly, Fräulein Stöhr seemed to prefer the Nordic-looking children...

Prussian obedience, order, and discipline as well as blind submission to Nazi ideology were Fräulein Stöhr's undisputed forte. In these efforts she was aided by two canes cut from a filbert bush, one thin and one thick. She used them for slight infractions.... Over the course of two years she used her filbert canes on my hands at least four times, three times for whispering answers to kids she had called on. Each time I had to leave my crowded bench and walk, embarrassed and infuriated, to the front of the classroom and onto the podium to receive a couple of stinging lashes on my outstretched hand.

(17) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987)

There had been a lot of changes in school, too (after 1933). Some had been barely noticed, others had been introduced as though with drums and trumpets. None of my neatly dressed, well-behaved primary-school mates questioned the new books, the new songs, the new syllabus, the new rules or the new standard script, and when - in line with national socialist educational policies - the number of PT periods was increased at the expense of religious instruction or other classes, and competitive field-events added to the curriculum, the less studious and the fast-legged among us were positively delighted.The rector spelled it out for us. "Physical fitness is everything! It is what the Führer wants for you. It is what you want in order to grow strong and healthy!"

In class, Frau Bienert, our form teacher, explained why a healthy mind could only be found in a healthy body, and - instead of two PT periods a week - the revised time-table featured a daily class and a compulsory weekly games afternoon. Running, jumping, throwing balls, climbing ropes, swinging on the bars or doing rhythmic exercises to music, we fitted smoothly into the new pattern of things, into a scheme which, for most of us, appeared to be an attractive feature of national socialism, for an hour spent in the gym or on the sports pitch seemed infinitely preferable to sweating over arithmetic or German grammar.

I loved the new physical-fitness programme, but not the loud, aggressive songs we had to learn, the texts of which our music teacher would rattle off in a funereal voice. But then, Fraulein Kanitzki had been born in the Cameroons and suffered from bouts of malaria, which, in our eyes, entitled her to some form of eccentricity. And it was no secret that she never raised her arm in the "Heil Hitler!" salute at the beginning of class or in the school corridors; she was always conveniently hugging sheets of music or books under her right arm, which prevented her from performing the prescribed motion. The new greeting was, after all, a bore. Arm up, arm down. Up, down. But it was the formal salute in Germany now, and everyone did as they were told, including my father.

(18) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998)

The common people spoke Alsatian, a German dialect, and had no trouble switching. But I, from a bourgeois background, spoke only French. My brother gave me a crash course, allowing me, three months later, to return to school... It was now obligatory for children to be sent to the local school. All Alsatian teachers were sent to Germany for Umschulung (retraining)... They were replaced by young teachers, some in Wehmacht uniforms... they were easy-going missionaries. In every class hung a portrait of the Führer, and every room was fitted with a Volksender, the word used for radio, on which we listened to Adolf Hitler every time he spoke....

As the teacher entered the class, the students would stand and raise their right arms. The teacher would say, For the Führer a triple victory, answered by a chorus of Heil! three times... Every class started with a song. The almighty Führer would be staring at us from his picture on the wall. These uplifting songs were brilliantly written and composed, transporting us into a state of enthusiastic glee...

The first hour of school was dedicated to history, especially to the rise of the Nazi movement and the lastest news of military victories. "We had a special copybook for this. Indoctrination was daily and systematic. Jazz, modern art, and comic strips were considered degenerate and forbidden. I could easily imagine Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, or Superman and their likes dutifully arrested by the Gestapo to serve in some hard labour squad....

We were promised a reward of money if we denounced our parents or our neighbours - what they said or did... We were told: Even if you denounce your parents, and if you should love them, your real father is the Führer, and being his children you will be the chosen ones, the heroes of the future...

Athletics, gymnastics, swimming, playing, and boxing were priorities. Then came German, history, geography, art, and music; after that biology, chemistry, physics, and math, and last, foreign languages.

(19) E. Amy Buller, Darkness Over Germany (1943)

There are for me four possibilities for the future and I must add I am very lucky because for most of my colleagues there are only two possibilities since they have no opportunities to go abroad, and having no money they cannot retire.

First then, I may decide that it is impossible to remain in this country where there is no longer any intellectual freedom and where education is being degraded by political interference. I can argue that all I believe about true education is now at stake and that it is quite impossible for me to allow political agents, often ignorant and stupid men, to interfere with my teaching of geography. Some of them don't seem to realize that any countries exist except Germany.

I have now an opportunity to go to America where I have been before. Shall I go? In many ways it would be a wonderful escape. My headmaster, who is new and young and a very keen Nazi - in fact he would not have this post if he were not a Party man - greatly hopes that I will leave. That is obvious, for he will get high praise if he can quickly obtain an all-Nazi staff.

The second way is for me to attempt to escape this revolution in my country altogether, by resigning from the school, digging in my garden and writing books. I could even begin to prepare books on the teaching of geography and history which will be much in demand when this disease of National Socialism is over. Perhaps I might even, in informal ways, help to challenge the Nazi teaching, since, if I leave the school, I should not be under authority.

The third way is to stay in my school but to defy the headmaster and refuse to give Nazi lessons on race. This would soon end in an outburst - I might even try to do it in front of the whole school and denounce Hitler and all his works. That would mean prison, and of course some of my colleagues are already there. Again the headmaster would be very happy, and you will understand what I mean when I say I doubt if my witness would have any value for the boys. A few might be influenced and later, perhaps more, but at the moment this new young headmaster has made a great impression on the majority of the boys. His predecessor was a bit elderly and conventional and the boys feel there is new life and action, and it is natural that they applaud this attack on scholarship, since It means they do not have to work so hard.

Perhaps I should take this third choice, go to prison and let a young Nazi take my job in the school. But let me tell you what I have done so far for this is the fourth possibility. I must add I am not happy and there is a constant strain. I remain on the staff and I pay lip service to all the Nazi school ceremonies and I do not show any open hostility, at least not enough to 'get the sack' but quite enough to make my position precarious and at times most unpleasant. I am trying through the teaching of geography to do everything in my power to give the boys knowledge and I hope later on, judgement, so that when, as they grow older, the Nazi fever dies down and it again becomes possible - to offer some opposition, they may be prepared. I never refer to the Party or to its teaching directly, and the boys are, I think, mostly unaware that I am trying deliberately to undermine it. There are four or five masters who are non-Nazis left in our school now, and we all work on the same plan. If we leave, four Nazis will come in and there will be no honest teaching in the whole school. 'Honest', did I say - are we being honest, I sometimes wonder? It is very exhausting as well as dangerous to live under the strain of a deliberate compromise with evil, and unless we remain all the time sensitive to its perils, we may so easily become dishonest with ourselves, and then we are no good to the boys or to anyone else. But if I went to America and left others to it, would that be honest, or are the only honest people those in prison cells? What do you think is honest - what would you do yourself?"

(20) Kurt Huber, a professor of philosophy at the University of Munich was executed for his criticism of the government of Nazi Germany. This is an extract from his final speech in court (20th February, 1943)

As a German citizen, as a German professor, and as a political person, I hold it to be not only my right but also my moral duty to take part in the shaping of our German destiny, to expose and oppose obvious wrongs.

What I intended to accomplish was to rouse the student body, not by means of an organization, but solely by my simple words; to urge them, not to violence, but to moral insight into the existing serious deficiencies of our political system. To urge the return to clear moral principles, to the constitutional state, to mutual trust between men.

A state which suppresses free expression of opinion and which subjects to terrible punishment - yes, any and all - morally justified criticism and all proposals for improvement by characterizing them as "Preparation for High Treason" breaks an unwritten law, a law which has always lived in the sound instincts of the people and which may always have to remain.

You have stripped from me the rank and privileges of the professorship and the doctoral degree which I earned, and you have set me at the level of the lowest criminal. The inner dignity of the university teacher, of the frank, courageous protester of his philosophical and political views - no trial for treason can rob me of that. My actions and my intentions will be justified in the inevitable course of history; such is my firm faith. I hope to God that the inner strength that will vindicate my deeds will in good time spring forth from my own people. I have done as I had to on the prompting of my inner voice.

(21) Inge Fehr, letter to Michael Smith (2nd April, 1997)

There was one Jewish girl in our class and we sent her to Coventry. Nobody spoke to her. Whenever she came into the playground, we all went into the opposite corner. My friend's father was high up in the Nazi Party and I was as bad as all the rest.

I was 11 and we were going to collect for the winter relief with the Hitler Youth when it was announced in the school hall that I would not be able to go. "Why not?" I asked. "Because your father is a Jew," they said. "It's impossible," I said. I had been taught that a Jew was the lowest form of life, my wonderful father could not be a Jew. Then I found out that my mother was a Jew too so I was classified as a full Jew.

We were having daily lessons in Race Knowledge, learning about the superiority of the German race. We were told that the... Jews had descended from Negroes. Miss Dummer, my form teacher, who was a patient of my father, took me aside after the first lesson and said: "Please ignore the rubbish I am forced to teach you."

Everything changed from then on. My father had to leave the hospital - two years earlier, on his 60th birthday, the Lord Mayor had written to him saying: "We hope Berlin will still have many, many years of your valuable service. But in 1934, all Jews had to leave public service and now a letter came telling him that he was forbidden to enter the hospital again.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

The Last Days of Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

Lord Rothermere, Daily Mail and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the German Workers' Party (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler the Orator (Answer Commentary)

Sturmabteilung (SA) (Answer Commentary)

Who Set Fire to the Reichstag? (Answer Commentary)

Appeasement (Answer Commentary)