Elsbeth Emmerich

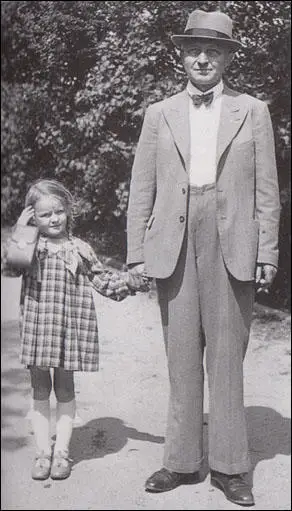

Elsbeth Emmerich was born in Düsseldorf, Germany, in 1933. Her father, Heinz Emmerich, was a butcher. The family lived with her mother's parents. Her grandfather, was a trade union official and a member of the German Communist Party, and was arrested several times by the Gestapo. (1)

In November 1939, her father was conscripted into the German Army. "While he was away fighting he wrote letters to all of us: to my mum, to us children, to his brother and all his seven sisters". (2)

On her first day at school Elsbeth took her teacher flowers. However, her teacher, Frau Borsig, was not impressed: "Frau Borsig... threw the flowers in the bin... One thing she did like to receive from us was Heil Hitler! Every day we had to greet her, and other grown-ups, with the salute. I was used to doing this, but it still embarrassed me. On my way to school one day I went into a busy shop without making the greeting, thinking no one would notice. But a shop assistant pounced on me, saying angrily, Don't you know the German greeting? She made me walk out and come back into the shop again, using the right greeting. I must have blushed to the roots of my long plaited hair as I held my arm out and said, Heil Hitler! in a pretend grown-up voice. Then she started talking loudly to the other customers about children's bad manners nowadays." (3)

Second World War

After the outbreak of the Second World War the children were taught to use air-raid sirens and gas-masks: "When the siren went we had to line up in twos and march in silence to the air raid shelter. It had bare brick walls and no windows. We were made to sit back-to-back on wooden benches. There were first-aid boxes, and gas masks hanging on hooks on the wall. They frightened me. We had to practise putting the gas masks on, and then sit there in silence till the siren sounded for the end of the drill. We didn't even get the chance to make those lovely rude noises you could make inside gas masks. Then we would go back to the classroom, still in silence." (4)

Elsbeth Emmerich's grandfather was opposed to Adolf Hitler. This often got him into trouble. On 20th April 1940, he had a visit from the police because he did not have a flag flying in the garden: "I couldn't hear what they were saying inside, but soon they came out into the garden and Granddad started to put up the flag-pole! Then he went indoors again, and emerged a minute later with the huge black and red flag with the swastika on it and hoisted it. He had an angry look on his face and seemed to be muttering. There was something going on he didn't like... I guessed that somehow the `nice' man had forced my grandad to do something he didn't want to. I only found out later that it had been Hitler's birthday that day. Everyone was supposed to put out a flag, and when the man saw there was no flag flying in our garden, he stopped to make sure that we put one up." (5)

Elsbeth's grandfather was taken into custody several times during the war: "The Gestapo kept arresting my grandfather, but he was always released after a while. He was one of the best men in his engineering works, and desperately needed, and with some clever persuasion his boss managed to get him freed. They tortured my grandfather at the prison, trying to make him give them the names of those who were working against the Nazi regime. It didn't succeed. They took Grandma, Mum and two of her sisters to the prison and made them cry out for Grandad to hear. That didn't work either. Eventually he had to go into hiding. He was declared vogelfrei, which translated means shoot to kill. He could not even let the family know where he was hiding and he lived in the woods eating berries and nuts to survive." (6)

In May 1940 Heinz Emmerich was involved in the invasion and occupation of France. In June, 1941, he took part in Operation Barbarossa. Two months he was fighting on the outskirts of Leningrad. He wrote: "Our position couldn't have been chosen better by the Devil himself. The worst things are all the snipers hidden in the trees. We are definitely sitting pretty." (7)

The Allied bombing of Düsseldorf became more intense. On one occasion a bomb landed on a neighbouring house. "There was the most frightening bang and roar and then it was quiet and we looked up. Grandma had been thrown against the wardrobe. The ceiling had come down and we could see the rafters. There was dust and a strange smell and a terrible mess everywhere. My mum grabbed us children. I don't know how she managed to take the three of us downstairs, when she was in bare feet and the stairs were strewn with rubble and broken glass." (8)

Later she was told by a boy in the street that the people living in the bombed house had been killed: "Rose and Albert are dead. Rose is decapitated and Albert's stomach is all out. My daddy found them." Elsbeth remarked that "he sounded almost proud, giving this terrible news. I could not believe what he said. I started trembling and tears welled up. I didn't want to know any more." (9)

Elsbeth's mother decided that the family must move out of the city. On 17th August 1941 the family moved to Altenkirchen, about 150 kilometers away, to live with Aunt Erna. "I liked Erna a lot. She let us have her room to sleep in. It was to have been hers and her fiancé's when they were married, but Werner was reported missing at Leningrad and never came home. Over her bed was a picture of the two of them together. They looked like a handsome couple." (10)

Death of Heinz Emmerich

Heinz Emmerich was still involved in the fighting in the Soviet Union: "From 9 to 12 September we attacked Leningrad and were 8 kilometres from the city. We are being relieved by the SS infantry who will take the town shortly. Well the SS can do anything, they are the only real troops fighting. We had heavy losses, because we had to take many bunkers and field positions.... Most companies are still only 40 men strong despite relief, but they say we will get more troops and then we are supposed to storm towards Moscow. Others say we shall march to the Ukraine, or that we should be sent home, but I don't believe that. I am just anxious to find out what will happen." (11)

The situation gradually got worse. On 25th November, 1941, he wrote: "Please forgive me not writing so much, but there's not much time. Every day we are in the fighting. Today was supposed to be a rest day but I think that we will attack. Since last night we have been under heavy Russian artillery fire... You can imagine how we are all looking forward to a get together back home, but who knows when that will be? It is difficult in attack, because in our division we have only about 20 operational tanks left out of 250 and they are clapped out. But that won't deter us, the last battalion on the field will be a German one. They are also saying that there will be 18 new Panzer divisions, better than the ones we had before." (12)

Heinz Emmerich was killed on 19th January, 1942: "I still remember the day the postman came. He was usually a very jovial man, but he hesitated when he asked my mother for her signature for the registered letter he had. It was a blue envelope with official stamps on the back. My mother took the letter trembling. She opened it, read with an ashen face, threw the letter on the table, and left crying for our bedroom. My sister Margret and I stood bewildered and I began to tremble. Then Frau Miiller picked up the letter. She looked shaken and reddened in the face from emotion. She read the letter. Then she said we'd better go and get Aunty Erna. Before that she showed it to me. I shook with every limb as I read that my father had been wounded in the right shoulder... I didn't read any further. I could not bear it. I could not bear my daddy being hurt and being so far away from us. I burst into tears and followed my mother into our room. She lay on the bed, crying. My little sister Elfi was next to her, but didn't know what to do. She wasn't two yet. Margret still didn't realize what had happened." (13)

German Girls' League

In 1943 Elsbeth Emmerich joined the German Girls' League (Bund Deutscher Mädel), the female branch of the Hitler Youth movement. "In High School, I became a member of the Jungmädel (Young Girls). We were all given the entry forms in class to fill in there and then, and told to take it home for our parents' signature.... I enjoyed being in the Jungmädel. We had to attend classes after school and learn about Adolf Hitler and his achievements. We did community work, singing to soldiers in hospitals and making little presents for them like bookmarks, or poems written out neatly. We also went on hikes and collected leaves and herbs for the war effort." (14)

The duties demanded of the German Girls' League (BDM) included regular attendance at club premises and camps run by the Nazi Party. (15) "We even went away to camp. I thought this might be exciting, but it wasn't like I imagined, even though it was right in the country in some lovely woodland. I was shouted at within minutes of arriving, for not picking up a bit of eggshell I'd dropped. We had to get up early each morning, standing to attention in the freezing cold and singing whilst the flag was being hoisted. Then someone stole my purse. My holiday was mainly doing what other people told you to all the time, like standing to attention and raising our arms for the Sieg Heil." (16)

Life in Nazi Germany

Elsbeth Emmerich's mother was a talented athlete in her youth and after the death of her husband she began coaching girls in the BDM. "My mother was becoming a sports personality. Even my teacher stopped in the street to talk to her about some sports event. Her new hobby appeared to agree with her. She totally immersed herself in it and seemed quite happy. But whenever you are feeling too happy something happens to spoil it."

One day an official of the Nazi Party arrived at the house. He said he had checked his records and discovered that she was not a party member. He brought with him an application form but she refused to join. He told her: "You realize you cannot keep your position as coach to our young girls, unless you are a member of the Party?" She still refused to join and therefore had to give up her coaching job. "I remember some of the conversations Mum had with various people after this. She learned that people who refused to become members of the Party simply lost their jobs. If you had a shop, for instance, you either became a Party member or closed down. All shopkeepers had to display a little sign in the window showing that they were a Party member." (17)

In her autobiography, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991), Elsbeth explained that the Second World War influenced all aspects of life: "The war entered the games we played. In one game we drew a circle on the ground and divided it up into countries. We had to throw a stone into the right space and if we missed we had to forfeit some land. Obviously, Hitler's ambition to get more territory for Germany - Lebensraum - was the idea for this game. The other war-time game was collecting shrapnel and mementos from crashed planes or bombs. We had not suffered from bombings in Altenkirchen so far, but a few planes had crashed in the area. We often watched the fighter planes, flying so low we could see the pilots in their cockpits. It was terrifying!" (18)

One day Elsbeth Emmerich saw an Allied plane shot down: "I remember the day when I saw an American pilot being led through the town handcuffed. I was in the school playground and could not keep my eyes off him. He was dressed in a very pale blue flying suit. I had never seen such clothing before. The pilot was a young man and he looked sad, his head hanging down so he seemed to stare at his hands. His step was slow and sluggish. My heart sank. This poor fellow. He was far away from home, so far away! As far as my dad had been! He was guarded by two men with rifles. I thought no one should ever treat another person like that. I wondered what would happen to him and felt afraid for him." (19)

Germany Defeated

In the final months of 1944 Elsbeth Emmerich began to encounter German soldiers in Altenkirchen. "At first it was just a trickle, but soon there was a steady flow of German soldiers retreating from the front. Altenkirchen was a meeting point for all routes, and the troops would stop to rest in the Marktplatz." She said they were clearly afraid. Soldiers told her: "If we're caught wearing a uniform, we're done for. And if we're caught not wearing a uniform, we're still done for - if one of those fanatical German officers finds us." (20)

The Allies increased their bombing attacks on Germany. After one raid, Elsbeth was shocked by what she saw when she left the air-raid shelter: "I could hardly believe what my eyes told me. Everything had changed! Where one street of houses had stood, there were heaps of bricks and rubble. On the other side there were parts of houses standing, with the indoors showing, upstairs bedrooms with wallpaper and fireplaces and curtains swinging in the smoke. The school-yard where we'd played the day before was a line of craters. There were fires and mountains of rubble where there had been a main road, and there was a stench from explosives and burning." The offensive continued and Elsbeth claimed that during the war bombing "killed two-thirds of all the people in Altenkirchen." (21)

The family moved to the village of Burbach. Elsbeth Emmerich points out in her autobiography that people believed that Allied soldiers would kill German civilians. "On this particular day we were playing quite happily together, when we heard shooting quite close. We stopped dead in our play, and listened. The sound of shooting came slowly nearer, then we heard the sound of gears changing and engines revving, from vehicles approaching through the woods. This was it! The Americans were coming! We still couldn't see anything, and we were all so frightened that we didn't have time to talk much or discuss what to do. We headed for the back door which led to the wash-kitchen. We looked around wildly for somewhere to hide. Werner ran across to the huge wash-tub, pulled himself up and with a wave of his legs, vanished into it. We followed him in, and all seven of us hid in the big wash-tub! Werner pulled the lid over our heads, leaving it a bit open, so that we could see the road and what was going on. The road bent around my aunty's house, so we had a perfect view along it." (22)

The following day American soldiers arrived at the farmhouse where they were staying: "The next morning, we were sitting at the breakfast table when some Americans came into the farmhouse. They gave us tinned powdered egg, and oats. I couldn't believe it. They were giving us food! And to top it all, they handed out chewing gum! We had never had chewing gum in our lives.... I became so happy and totally relieved and exhilarated when I realized that the Americans were not 'the enemy' as I had been taught, but normal human beings, friendly and generous. No one was being shot and no one was being tortured. I didn't have to plead for my mother or my sisters' lives. I cannot remember ever feeling happier or more relieved than I did after the Americans came to our little village." (23)

Elsbeth Emmerich claimed that she had learnt important lessons in the war: " People I had known throughout the war, people who had run off eagerly in their brown uniforms to the Nazi rallies, suddenly hated Hitler. People like the man in the flat above us. We'd often passed him on the stairs in his fine SA gear. Now he was saying how awful Hitler was. At the age of 11, such people gave me my first real lesson in human nature. I never again believed something just because someone told me so. I realized I had to make up my own mind about what I thought. I had to be in charge of my own life, and decide what was right and wrong... I had learnt not to believe everything people said. I had realized that other nations are made up of people just like ourselves, and that to call other people the enemy is a tactic used by the people who make propaganda." (24)

Elsbeth Emmerich moves to London

Elsbeth Emmerich fell in love with a British soldier and in May 1958 she moved to London. Over the next few years she gave birth to several children, who in time gave her eleven grandchildren. When she was fifty-eight, she published her autobiography, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991).

Primary Sources

(1) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991)

Frau Borsig... threw the flowers in the bin... One thing she did like to receive from us was "Heil Hitler!" Every day we had to greet her, and other grown-ups, with the salute. I was used to doing this, but it still embarrassed me. On my way to school one day I went into a busy shop without making the greeting, thinking no one would notice. But a shop assistant pounced on me, saying angrily, "Don't you know the German greeting?" She made me walk out and come back into the shop again, using the right greeting. I must have blushed to the roots of my long plaited hair as I held my arm out and said, "Heil Hitler!" in a pretend grown-up voice. Then she started talking loudly to the other customers about children's bad manners nowadays.

(2) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991)

The war followed us to school, with the sound of the air raid drill. When the siren went we had to line up in twos and march in silence to the air raid shelter. It had bare brick walls and no windows. We were made to sit back-to-back on wooden benches. There were first-aid boxes, and gas masks hanging on hooks on the wall. They frightened me. We had to practise putting the gas masks on, and then sit there in silence till the siren sounded for the end of the drill. We didn't even get the chance to make those lovely rude noises you could make inside gas masks. Then we would go back to the classroom, still in silence.

The drill used to upset me so much that when the siren went one day for a real alarm, I just ran of home. All I could think of was being with my mum and sisters and grandparents. An air raid warden shouted after me in the street, but I kept on running. I got home exhausted but safe.

(3) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991)

Granddad came to the door and invited the man in, while I stood on the step with the girl in the lovely dress. I couldn't hear what they were saying inside, but soon they came out into the garden and Grand ad started to put up the flag-pole! Then he went indoors again, and emerged a minute later with the huge black and red flag with the swastika on it and hoisted it. He had an angry look on his face and seemed to be muttering. There was something going on he didn't like.

When the flag was up and the swastika was billowing in the breeze the man and the girl left. Watching them walk away down the road, looking at the houses, I suddenly felt suspicious of them. I guessed that somehow the `nice' man had forced my Grand ad to do something he didn't want to.

I only found out later that it had been Hitler's birthday that day. Everyone was supposed to put out a flag, and when the man saw there was no flag flying in our garden, he stopped to make sure that we put one up. I had no idea at the time that no flags fluttered in my family's hearts for Herr Hitler. That was why no one had said it was his birthday.

(4) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991)

He had been known to them since before the war for his anti-Nazi activities, and being a union shop-steward and a member of the Communist Party. There had been many visits to the house, though I hadn't really taken any notice of them. They had been watching him long before my parents married. When Dad was 18, he was beaten up by young fascist thugs because they knew he was dating my mum, and they didn't like Grand ad's anti-fascist views.

The Gestapo kept arresting my grandfather, but he was always released after a while. He was one of the best men in his engineering works, and desperately needed, and with some clever persuasion his boss managed to get him freed.

They tortured my grandfather at the prison, trying to make him give them the names of those who were working against the Nazi regime. It didn't succeed. They took Grandma, Mum and two of her sisters to the prison and made them cry out for Grand ad to hear. That didn't work either. Eventually he had to go into hiding. He was declared vogelfrei, which translated means "shoot to kill". He could not even let the family know where he was hiding and he lived in the woods eating berries and nuts to survive.It would have been much too dangerous to let children in on the truth about these things at the time. We only learned about them after the war, so that many things became clear then which I had never really understood before. That was when I found out why there were times when I couldn't go with Grandma when she took a cooked lunch to my Grand ad, in pots wrapped in tea-towels. I could go when she was taking it to the factory, but not when she was taking it to the prison.

(5) Heinz Emmerich, letter to his sister (13th September, 1941)

Dear Franzi, I am still well and healthy. We are a few kilometers from Leningrad and hope that when you receive this letter I will still be healthy and the city will be taken... How are things with Aunty Mariechen? Is she married yet? How's everything at home? And how is the weather? From Monday afternoon the weather here was good, only the nights are cold and one has to take walks to keep warm, and since this morning it's been raining again. We could have done with a few more days clear weather for our aircraft. They could have supported us. I wish I knew how all this was going to end. I must close now. Hope you are all well. Greetings from your brother Heinz.

From 9 to 12 September we attacked Leningrad and were 8 kilometers from the city. We are being relieved by the SS infantry who will take the town shortly. Well the SS can do anything, they are the only real troops fighting. We had heavy losses, because we had to take many bunkers and field positions.... Most companies are still only 40 men strong despite relief, but they say we will get more troops and then we are supposed to storm towards Moscow Others say we shall march to the Ukraine, or that we should be sent home, but I don't believe that. I am just anxious to find out what will happen.

(6) Heinz Emmerich, letter to his sister (25th November, 1941)

Dear Franzi, best wishes from Russia from your brother Heinz. I thank God I am still alive and well, and hope you are too. Please forgive me not writing so much, but there's not much time. Every day we are in the fighting. Today was supposed to be a rest day but I think that we will attack. Since last night we have been under heavy Russian artillery fire... You can imagine how we are all looking forward to a get together back home, but who knows when that will be? It is difficult in attack, because in our division we have only about 20 operational tanks left out of 250 and they are clapped out. But that won't deter us, the last battalion on the field will be a German one. They are also saying that there will be 18 new Panzer divisions, better than the ones we had before. Dear Franzi, I will close now, a thousand greetings, your brother Heinz.

(7) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991)

I still remember the day the postman came. He was usually a very jovial man, but he hesitated when he asked my mother for her signature for the registered letter he had. It was a blue envelope with official stamps on the back. My mother took the letter trembling. She opened it, read with an ashen face, threw the letter on the table, and left crying for our bedroom. My sister Margret and I stood bewildered and I began to tremble. Then Frau Miiller picked up the letter. She looked shaken and reddened in the face from emotion. She read the letter. Then she said we'd better go and get Aunty Erna. Before that she showed it to me. I shook with every limb as I read that my father had been wounded in the right shoulder... I didn't read any further. I could not bear it. I could not bear my daddy being hurt and being so far away from us. I burst into tears and followed my mother into our room. She lay on the bed, crying. My little sister Elfi was next to her, but didn't know what to do. She wasn't two yet. Margret still didn't realize what had happened.

Frau Muller came in with our coats. She dressed us up warmly and told us to show the letter to our relatives in the town. We both cried on the way. I'm sure Margret didn't know why, she just cried because we all cried. At the end of Hochstrasse a young Hitler Youth asked what was the trouble, why we were crying. "My daddy is wounded," I said and held out the letter. He read it and tried to console us, saying, "Don't worry, being wounded means that he'll soon be home on leave. Don't cry any more.' With that he sent us on our way.

I am sure he'd read the entire letter, which went on to say how my father died a few days later. Obviously he didn't want to upset us any further. We walked solemnly through the small town to our aunt's house. We walked. up the stairs, and in the door. I held the letter in my outstretched hand and sank to the ground near the door.

(8) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991)

In High School, I became a member of the Jungmädel (Young Girls). We were all given the entry forms in class to fill in there and then, and told to take it home for our parents' signature.... I enjoyed being in the Jungmädel. We had to attend classes after school and learn about Adolf Hitler and his achievements. We did community work, singing to soldiers in hospitals and making little presents for them like bookmarks, or poems written out neatly. We also went on hikes and collected leaves and herbs for the war effort.

We even went away to camp. I thought this might be exciting, but it wasn't like I imagined, even though it was right in the country in some lovely woodland. I was shouted at within minutes of arriving, for not picking up a bit of eggshell I'd dropped. We had to get up early each morning, standing to attention in the freezing cold and singing whilst the flag was being hoisted. Then someone stole my purse. My "holiday" was mainly doing what other people told you to all the time, like standing to attention and raising our arms for the Sieg Heil.

(9) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991)

My mother was becoming a sports personality. Even my teacher stopped in the street to talk to her about some sports event. Her new hobby appeared to agree with her. She totally immersed herself in it and seemed quite happy. But whenever you are feeling too happy something happens to spoil it.

This time it was another knock at the door and the appearance of a stranger. A man with a notebook and pencil and a Nazi pin in his lapel. He said that he'd heard about my mother and her achievements. He had assumed that she was a member of the Party and only found out that she was not when he checked his records. (Of course, anyone who referred to the "Party" meant the Nazi Party. There was only one.)

No doubt that was just an oversight, he went on, and she would join? He had his pencil at the ready but my mother froze over and said firmly "NO". She did not want to become a member of the Party. He wanted to know her reasons and she said that she had reasons of her own. He didn't understand. "You realize you cannot keep your position as coach to our young girls, unless you are a member of the Party?" My mum said surely coaching had nothing to do with politics, and that being a Party member would not make her a better coach. However, the man with the Party pin in his lapel knew better and my mother had to give up a much cherished job.

I remember some of the conversations Mum had with various people after this. She learned that people who refused to become members of the Party simply lost their jobs. If you had a shop, for instance, you either became a Party member or closed down. All shopkeepers had to display a little sign in the window showing that they were a Party member.

(10) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991)

The war entered the games we played. In one game we drew a circle on the ground and divided it up into countries. We had to throw a stone into the right space and if we missed we had to forfeit some land. Obviously, Hitler's ambition to get more territory for Germany - Lebensraum - was the idea for this game.

The other war-time game was collecting shrapnel and mementos from crashed planes or bombs. We had not suffered from bombings in Altenkirchen so far, but a few planes had crashed in the area. We often watched the fighter planes, flying so low we could see the pilots in their cockpits. It was terrifying!

(11) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991)

I remember the day when I saw an American pilot being led through the town handcuffed. I was in the school playground and could not keep my eyes off him. He was dressed in a very pale blue flying suit. I had never seen such clothing before. The pilot was a young man and he looked sad, his head hanging down so he seemed to stare at his hands. His step was slow and sluggish. My heart sank. This poor fellow. He was far away from home, so far away! As far as my dad had been!

He was guarded by two men with rifles. I thought no one should ever treat another person like that. I wondered what would happen to him and felt afraid for him.

(12) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991)

On this particular day we were playing quite happily together, when we heard shooting quite close. We stopped dead in our play, and listened. The sound of shooting came slowly nearer, then we heard the sound of gears changing and engines revving, from vehicles approaching through the woods. This was it! The Americans were coming! We still couldn't see anything, and we were all so frightened that we didn't have time to talk much or discuss what to do. We headed for the back door which led to the wash-kitchen.

We looked around wildly for somewhere to hide. Werner ran across to the huge wash-tub, pulled himself up and with a wave of his legs, vanished into it. We followed him in, and all seven of us hid in the big wash-tub! Werner pulled the lid over our heads, leaving it a bit open, so that we could see the road and what was going on. The road bent around my aunty's house, so we had a perfect view along it.

After a minute or two of silence and heavy breathing, we saw them! Americans in their jeeps, shooting! But what was that? Their rifles were pointed towards the sky. They weren't shooting at anybody. They were just shooting in the air!

That was a relief! But we still preferred to stay in our hiding place for a while until it became too uncomfortable. After a few minutes everything was quiet, so we all crept out. The Americans had gone again. A convoy had driven through the village and gone on. We couldn't wait for our mothers to get back home to tell them.We were all frantic with excitement when they returned. My mother already knew that the Americans had come. She just stayed as calm as ever and told us not to worry. Then, while we were all in the kitchen, the door bell went. My aunty answered the door. Outside stood the most gigantic American one could imagine. He must have been well over six foot and his uniform made him look twice as big. He had a round of ammunition around his waist and a tiger head on his breast pocket. Immediately, my heart trembled again and I tried to be invisible.

"Does anyone speak English?" he asked.

The woman from Troisdorf went forward and said, "Just a little".

I had started to learn English in school and thought, I could have said that. But I was too afraid.

I was still only breathing shallowly, uncertain whether they would suddenly decide to do something to us. After all, we had been told so many things about the enemy, and now they were here; who knew what might happen.

The American called one of the other soldiers and they both went through the house, looking at every room. When he finished his inspection, we were informed, with the woman from Troisdorf interpreting, that the house was needed by the American forces. We were told what we could take along and what we had to leave behind. My mother's radio and record player were two of the things we had to leave behind.

My aunty went to stay with Aunty Paula at the bottom of the village, while we went back to Grand ad's friend, where we had slept before in the loft. I don't know where the family from Troisdorf went. They may even have decided to return to Troisdorf.

That same evening, we were already in bed in our hayloft when we saw a group of Americans just outside the farmhouse. They were trying to talk to some young girls. They gave them cigarettes and chewing gum. We were amazed!

The next morning, we were sitting at the breakfast table when some Americans came into the farmhouse. They gave us tinned powdered egg, and oats. I couldn't believe it. They were giving us food! And to top it all, they handed out chewing gum! We had never had chewing gum in our lives. Soon there were boys and girls in the village following the Americans around calling out, "Cigarettes, please!" or "Chewing gum, please!" They seemed to like being followed.

They sat in their jeeps throwing out chewing gum and cigarettes. For the first time in my life I saw black people. They too were huge!

During the next few days every so often we heard shots. "Oh, that will be an SS man," the people in the village said.

Later we found out that the Americans had tried shooting at fish in the river.

I became so happy and totally relieved and exhilarated when I realized that the Americans were not "the enemy" as I had been taught, but normal human beings, friendly and generous. No one was being shot and no one was being tortured. I didn't have to plead for my mother or my sisters' lives.

I cannot remember ever feeling happier or more relieved than I did after the Americans came to our little village.

(13) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991)

People I had known throughout the war, people who had run off eagerly in their brown uniforms to the Nazi rallies, suddenly hated Hitler. People like the man in the flat above us. We'd often passed him on the stairs in his fine SA gear. Now he was saying how awful Hitler was. At the age of 11, such people gave me my first real lesson in human nature. I never again believed something just because someone told me so. I realized I had to make up my own mind about what I thought. I had to be in charge of my own life, and decide what was right and wrong... I had learnt not to believe everything people said. I had realized that other nations are made up of people just like ourselves, and that to call other people the enemy is a tactic used by the people who make propaganda.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) page 40

(2) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) page 10

(3) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) pages 27-28

(4) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) page 28

(5) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) pages 36-37

(6) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) pages 40-41

(7) Heinz Emmerich, letter to his sister (7th August 1941)

(8) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) pages 52-53

(9) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) page 55

(10) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) page 60

(11) Heinz Emmerich, letter to his sister (13th September, 1941)

(12) Heinz Emmerich, letter to his sister (25th November, 1941)

(14) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) page 87

(15) Richard Grunberger, A Social History of the Third Reich (1971) page 335

(16) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) page 88

(17) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) page 94

(18) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) page 97

(19) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) page 98

(20) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) page 106

(21) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) pages 110-113

(22) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) page 121

(23) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) pages 125-126

(24) Elsbeth Emmerich, Flying a Flag for Hitler (1991) pages 128 and 136