Tomi Ungerer

Tomi Ungerer, the youngest son, of Theodore Ungerer and Alice Essler Ungerer, was born in Strasbourg, France, on 28th November 1931. His father, who produced astronomical clocks, died in 1936. The family now moved to Logelbach, near Colmar. (1)

His mother, was born in the town when it was part of Germany but after the Versailles Peace Treaty it was now under the control of France. When Adolf Hitler took power in 1933 he made it clear that his main objective was to restore terrority lost as a result of Germany's defeat in the First World War. (2)

On the outbreak of the Second World War the people living in the Alsace region became very nervous. Tomi Ungerer later recorded: "There was fear and dread in the air... On September 1, 1939, three hundred and eighty thousand Alsations, of which one hundred thousands were in Strasbourg, were ordered to pack a suitcase, a blanket, and enough food for four days within twenty-four hours. In trains, sometimes in cattle wagons, they were moved to the south-west of France. There they were not exactly welcome, especially because most of them had German accents and spoke little French." (3)

Tomi Ungerer in Alsace

Tomi Ungerer's family stayed, convinced that the French Army would be able to protect them. However, on 17th June, 1940, the German Army invaded. Four days later Adolf Hitler arrived at the Glade of the Armistice memorial that marked the place where Germany had surrendered in November, 1918. The American journalist, William L. Shirer, witnessed his arrival: "I observed his face. It was grave, solemn, yet brimming with revenge. There was also in it, as in his springy step, a note of the triumphant conqueror, the defier of the world. There was something else... a sort of scornful, inner joy at being present at this great reversal of fate - a reversal he himself had wrought." (4)

Tomi watched the German troops enter his village: "The German regiment was ordered to stop in front of our house. The guns were propped upright nearly in pyramids of three while the unit of young smiling faces broke out, laughing and joking. A horse-drawn field kitchen pulled up, and lunch was served. Fascinated, I went out on the sidewalk, and a beaming soldier offered me a taste of his soup. Then they marched on. They were not the hordes of Huns I had so vividly imagined, and what's more, they seemed nice, even cordial." (5)

An estimated 80% of the Jews in France lived in Alsace. Over 22,000 indigenous Jews from the region were deported to France, together with 6,500 German Jews. (6) According to Tomi Ungerer: "On the 16th of July all Jews who remained in Alsace were told that they had twenty-four hours to pack a suitcase and enough food for five days. They were allowed 2,000 francs per person, but gold, jewelry, and wedding rings were to be left behind... They were deported to France in convoys... Within six months Colmar was to lose one-third of its population, while shops, houses, furniture, and all assets were confiscated." (7)

Germany was immediately proclaimed the official language: "The common people spoke Alsatian, a German dialect, and had no trouble switching. But I, from a bourgeois background, spoke only French. My brother gave me a crash course, allowing me, three months later, to return to school... It was now obligatory for children to be sent to the local school. All Alsatian teachers were sent to Germany for Umschulung (retraining)... They were replaced by young teachers, some in Wehmacht uniforms... they were easy-going missionaries. In every class hung a portrait of the Führer, and every room was fitted with a Volksender, the word used for radio, on which we listened to Adolf Hitler every time he spoke." (8)

Anti-Semitism

The new teachers encouraged hostility to Jews. German children were ordered to write essays with titles such as "The Jews are our misfortune". Rebecca Weisner suffered a great deal in her German school: "When I was six, Hitler came to power. I started school in April 1933, just at the same time... There were some German girls I was friends with - we grew up together - and, all of a sudden, one day I come down and they call me dirty Jew. My friends, the friends I grew up with! I couldn't comprehend it. I would say to my mother, Why do they call me dirty? I am not dirty. And she said, You had better get used to it. You're Jewish, and that is what you have to learn. So just take it. But I didn't want to take it. I fought." (9)

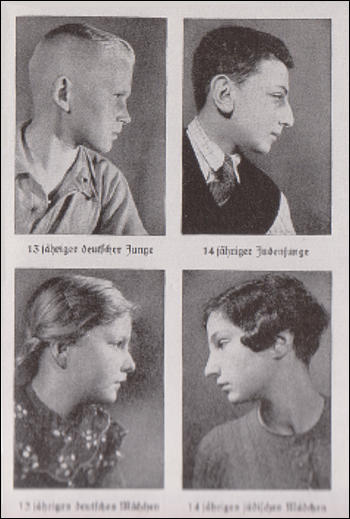

One of Tomi's first homework assignments was to draw a Jew. He did not know any Jews and asked his mother what he should do. She replied, "I think they want you to draw a man wearing glasses, with dark hair, a big nose, thick lips, and smoking a cigar." Over the next few weeks he discovered that his teachers wanted him to see Jews in a certain way: "At school the depiction of Jews was so exaggerated that for us they seemed like fairy tale figures dragging huge sacks of gold." (10)

In his autobiography, A Childhood under the Nazis (1998), Tomi Ungerer commented that one of the textbooks that he was forced to use was the anti-Semitic book, The Jewish Question in Education, which contained guidelines for the "identification" of Jews (11). Written by Fritz Fink, with an introduction by Julius Streicher it included passages such as the "Jews have different noses, ears, lips, chins and different faces than Germans" and "they walk differently, have flat feet... their arms are longer and they speak differently." (12)

Jewish children in German schools suffered terribly from bullying: "The children called me Judenschwein (Jewish pig)... When I came home I was crying and said, What is a Judenschwein? Who am I? I didn't know who I was. I was only a kid. I didn't know what I was, Jew or not Jew. There were many times when I was beaten up coming from school. I remember one teacher who had something against me because I was a Jew in his class. Every time when I must have been unruly, he used to pull me up front and bend me over and whip me with a bamboo stick." (13)

Tomi Ungerer was grateful that his family had no Jewish blood. "Every family was given an Ahnenpass, a kind of passport with one's family tree going back four generations, 'proving' that no Jewish blood had soiled our 'Aryan' blood." (14) He was aware of the setting up of concentration camps for Jews and political prisoners: "There was a camp in Schirmeck and later one in the Vosges, the Natzweiler-Struthof. We knew about them, and stories circulated that the wartime soap was manufactured out of Jewish victims." (15)

Germanization

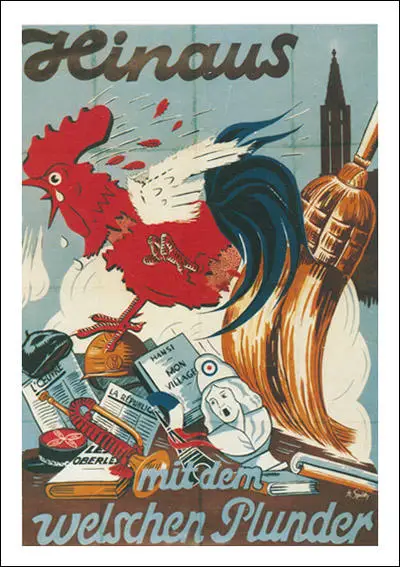

All the names of streets in the Alsace region were changed. All main streets became Adolf Hitler Strasse. "Alsatian village names were literally unpronounceable by the French, creating puddles of confusion reflecting the problematic nature of our identity... the French have great difficulties dealing with untranslatable names of villages like Mittelschafholzheim."

Attempts were made to change the way people saw the past. As Tomi Ungerer pointed out: "Every town and village had its memorial commemorating the dead who had fallen under various uniforms. There as well, the plaques were changed, and all the people who died for France suddenly died for Germany." (16)

There were also other changes: "The French beret was a Gallic symbol, and it was forbidden to wear one... You were punished with a fine of 150 Reichmarks and six months in prison if caught wearing one. This applied to Alsace only; in Germany a few miles away across the Rhine you could wear a beret without being punished. Some parents turned this into a joke and sent their children to school wearing absurd headgear." (17)

Several measures were taken against the French language: "It was forbidden to own any French books. We children were given wagons to go from house to house and collect them for burning, a joke because everyone simply hid them in boxes, and all we collected were old papers and magazines. You had to obtain official permission to consult a French dictionary, and any pictures with French captions and French diplomas were forbidden and had to go... The use of French was strictly forbidden. A simple Bonjour or Merci was first punished by a fine and, later, immediate arrest and a jail sentence." (18)

Nazi Education

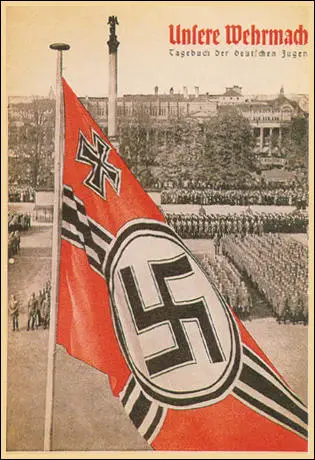

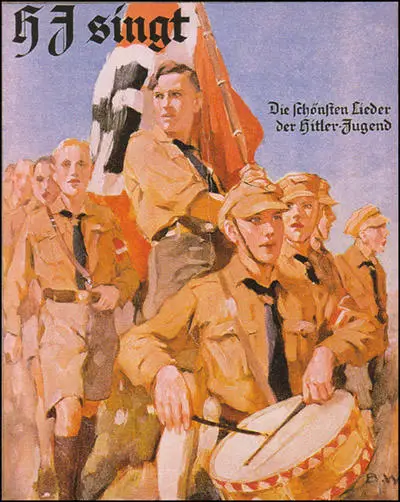

In Nazi Germany it was compulsory to join the Hitler Youth. The government issued a law conscripting all young people into the Hitler Youth on the same basis as they were drafted into the German Army. "Recalcitrant parents were warned that their children would be taken away from them and put into orphanages or other homes unless they enrolled." (19)

Children could not attend school unless they were members of the organization. Alice Ungerer did not want her son to be a member and had a meeting with the local head of the Nazi Party: "In her best High German explained that upper crust people like the Ungerers, the elite of the Reich, had no time wasting their energies with the common rabble, that these people needed an education that she and her family didn't need. Heil Hitler, Ja wohl, dispensation granted." Tomi Ungerer was disappointed by this decision: "It was with some envy that I watched my school pals in splendid uniforms marching off for fun and sports. These uniforms were all given out for free in Alsace. And what I coveted the most was the Hitler Youth dagger that came with it." (20)

At school the students were taught to worship Adolf Hitler: "As the teacher entered the class, the students would stand and raise their right arms. The teacher would say, For the Führer a triple victory, answered by a chorus of Heil! three times... Every class started with a song. The almighty Führer would be staring at us from his picture on the wall. These uplifting songs were brilliantly written and composed, transporting us into a state of enthusiastic glee." (21)

The first hour of school was dedicated to history, especially to the rise of the Nazi movement and the latest news of military victories. "We had a special copybook for this. Indoctrination was daily and systematic. Jazz, modern art, and comic strips were considered degenerate and forbidden. I could easily imagine Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, or Superman and their likes dutifully arrested by the Gestapo to serve in some hard labour squad... We had special classes building model airplanes (to make us future pilots in the Luftwaffe, of course." (22)

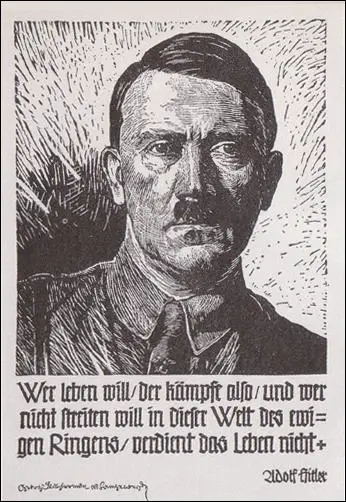

The first thing that Tomi Ungerer had to write in his copybook had to be memorized: "Our Führer is named Adolf Hitler. He was born the 20th of April 1889 in Braunau. Our Führer is a great soldier and tireless worker. He delivered German from misery. Now everyone has work, bread, and joy. Our Führer loves children and animals." His first homework was to draw the swastika flag and copy out the following quote from Hitler: "In the swastika lies the mission to fight for the victory of the Aryan race, as well as the triumph of the concept of creative labour, which always, in itself, was anti-Semitic, and always will be." (23)

In every schoolbook was an illustration of Hitler with one of his sayings as a frontispiece. Tomi Ungerer claims that his schoolbooks were strewn with pages of sayings from the Führer: "Learn to sacrifice for your fatherland. We shall go onwards. Germany must live. In your race is your strength. You must be true, you must be daring and courageous, and with each other form a great and wonderful comradeship." (24)

whoever refuses to fight in this world of eternal challenge has no right to live." (c. 1940)

Teachers encouraged members of the Hitler Youth to inform on their parents. For example, they set essays entitled "What does your family talk about at home?" According to one source: "Parents... were alarmed by the gradual brutalisation of manners, impoverishment of vocabulary and rejection of traditional values... Their children became strangers, contemptuous of monarchy or religion, and perpetually barking and shouting like pint-sized Prussian sergeant-majors." (25)

Tomi Ungerer claims that his teachers encouraged his students to inform on his parents. "We were promised a reward of money if we denounced our parents or our neighbours - what they said or did... We were told: Even if you denounce your parents, and if you should love them, your real father is the Führer, and being his children you will be the chosen ones, the heroes of the future." (26)

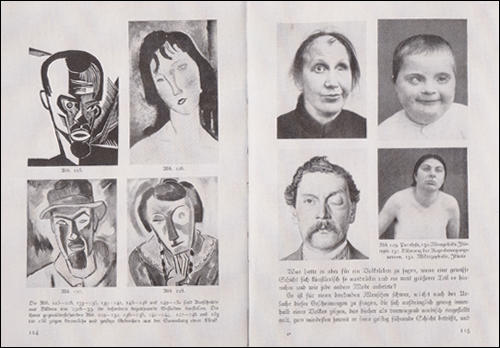

Art was Tomi Ungerer favourite subject. His teacher praised him for his work and he was told: "The Führer needs artists - he himself is one." The government had taken complete control of the art world. "Under the Nazis, painters and sculptors were paid a monthly salary from the state." Textbooks used in the classroom were very hostile to modern art, something that was considered to be degenerate. Below is a school textbook that provides a comparative study between modern paintings and deformed humans. For example, the Amedeo Modigliani (plate 126) is compared to a person with Down's Syndrome. (27)

The Nazi government made changes to the school curriculum in the countries they controlled. Education in "racial awareness" began at school and children were constantly reminded of their racial duties to the "national community". Biology, along with political education, became compulsory. Children learnt about "worthy" and "unworthy" races, about breeding and hereditary disease. "They measured their heads with tape measures, checked the colour of their eyes and texture of their hair against charts of Aryan or Nordic types, and constructed their own family trees to establish their biological, not historical, ancestry.... They also expanded on the racial inferiority of the Jews". (28)

As Louis L. Snyder has pointed out: "There were to be two basic educational ideas in his ideal state. First, there must be burnt into the heart and brains of youth the sense of race. Second, German youth must be made ready for war, educated for victory or death. The ultimate purpose of education was to fashion citizens conscious of the glory of country and filled with fanatical devotion to the national cause." (29)

Tomi Ungerer points out that his school placed great importance in physical education: "Athletics, gymnastics, swimming, playing, and boxing were priorities. Then came German, history, geography, art, and music; after that biology, chemistry, physics, and math, and last, foreign languages."

All children were expected to help the war effort: "Each day, students showed up with bags containing everything fit to be recycled-papers, rags, tin cans, bottles, bones, boxes, toothpaste tubes, even horse chestnuts - all part of the war effort. In the winter of 1942 in Alsace they collected 3,963,699 old woolen scarves, and 479,589 pairs of old socks! All of these were stored in the huge attic of our school. Every Saturday afternoon the whole population had to report to the potato fields, with bottles in their hands, to pick potato bugs (Colorado beetles) that had suddenly appeared, which we were told was part of a 'Negro Judeo-American' conspiracy to starve the German people." (30)

Alsace and the German Reich

On 16th June, 1940, General Henri Philippe Pétain became the Prime Minister of France. He agreed to follow the orders of Adolf Hitler. (31) The following year he agreed to Alsace becoming part of the German Reich: "June 21, 1941 remains a date of infamy, when France - under Pétain's Vichy - with servile cowardice officially agreed to the annexation of Alsace to the German Reich. Much damage had already been done, but now it meant that we were fully fledged citizens of Germany." (32)

This meant that the Germans could draft young Alsatians into the military. Over 130,000 served in the German Army on the Eastern Front. Everybody now had to join the Nazi Party. Girls and boys aged eighteen had to serve one year in the Reich Arbeitsdienst (Labour Service). It provided cheap labour for the government. (33) Tom was too young to serve but his sister was sent to Germany to do farm work. His brother, Bernard, served in the army until he was captured by the Americans in 1945.

During the final stages of the Second World War there were terrible food shortages in Alsace. "The quest for food kept us all very busy. I was responsible for the chickens... After the harvest I would take them out into the fields. They followed me like sheep and gorged themselves on fallen grain. It was on one of these occasions in August 1944 that a low-flying American P-38 Lightning plane decided to use me for shooting practice. I hit the ground face down and the chickens scattered while bullets strafed the ground. This was when American pilots had orders to shoot anything that moved.... The German propaganda had a heyday denouncing the inhuman tactics of the Negro-Judeo-Americans." (34)

In 1945 all sixteen-year-olds in the region were drafted into the army. At school Tomi Ungerer was trained to use weapons, including the Panzerfaust, that had the ability to destroy tanks. As the Allies approached the town came under fire and the family spent much of its time in the cellar. However, during a visit to Colmar he narrowly escaped being killed by an exploding shell: "Further up the street, Herr Berchtold, a stately, fat, mustached neighbour... lay in a pool of blood, partially decapitated. He was the first dead person I had ever seen." (35)

The German Army suffered 14,000 dead defending Colmar. Tanks arrived on 2nd February, 1945. "The first one was a Sherman; it stopped, the top opened, and for the first time we heard a French voice - an officer with the French First Army. He gave us some Camel cigarettes." The American soldiers were not so friendly. "The Americans... held us at gun point while searching the buildings for German snipers and plundering our home for food and souvenirs. They walked away with our last two pots of jam, which we had kept to celebrate the day of freedom." (36)

Post-War Education

At the end of the war the French government took control of the schools in Alsace: "We were given new blue copybooks - a present from Canada. The janitor would come every day to fill the ink pots on the desks and distribute vitamin cookies. I was to be quickly disillusioned seeing the French making the same mistakes as the Nazis - the entire beautiful school library was emptied and burned in the yard, along with films and everything of German origin. Goethe and Schiller went the same way as Heine and Thomas Mann. Even the plaster busts of Greek and Roman philosophers were smashed."

The authorities were highly suspicious of those who had not fled from the German Army: "The changes in school were traumatic for me and my friends. It was forbidden to speak Alsatian or German, and we were punished for every word uttered.... We had a crop of new teachers, some of them French, and others were Alsatians who had chosen to stay in France during the war. For some we were nothing but scum, a brood of collaborators. Alsatian would still be forbidden twenty-five years after the war - a deep blow to our identity."

Tomi Ungerer felt victimized by some of the teachers: "Our French teacher was a born sadist, a big fat pink toad who wore dark glasses. A necrophiliac, in a trance-like state he would rant on about the beauty of cadavers. When Alsatian students were called up to recite he would grab one of our ears; the moment we stopped reciting he twisted the ear until we were on our knees. The French boys were automatically good students and were not subject to this treatment." Tomi was described in his school report as "this pupil is a liar" and that he was "perverse and subversive". (37)

Tomi Ungerer - Artist

Tomi Ungerer moved to New York City in 1956. According to Sarah Cowan: "Ungerer was lured to New York City at the height of print, when publications offered vast opportunities for creative illustrators. Without contacts or even a high school diploma, Ungerer impressed art directors with his idiosyncratic drawing style and witty candor. He became sought after for advertising and editorial work, and most prominently, his unconventional children’s books, which featured society’s most repulsive characters - robbers, snakes, pigs, beggars - as compassionate protagonists." (38)

Soon after arriving he published his first book for children, The Mellops Go Flying (1957). This was followed by Mellops Go Diving for Treasure (1957), Crictor (1958), The Mellops Strike Oil (1958), Adelaide (1959), Christmas Eve at the Mellops (1960), Emile (1960), Rufus (1961) and The Three Robbers (1961). He also did illustration work for the New York Times, Life Magazine, Harper's Bazaar, Esquire and The Village Voice.

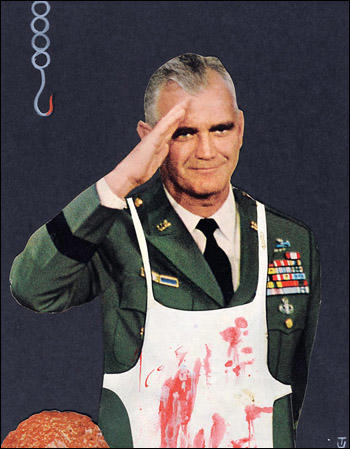

In the 1960s he became involved in politics and became well-known for his posters in support of Civil Rights and against the Vietnam War. "As the 1960s went on and Ungerer became increasingly active in the Civil Rights and anti-Vietnam movements, a less optimistic tone pervades his work." (38)

Tomi Ungerer would later credit the graphic ferocity of his work to having grown up in Nazi-occupied Alsace. “The irony is, this is a style that I got from Hitler. My Vietnam posters, I did them all one day in a total state of anger, one after the other.” Jules Feiffer has argued: “As brilliant as the kids’ books are, and as brilliant as his other work, when I see them reproduced still I find those political posters from the sixties shocking to look at.” (39)

His adult books such as The Underground Sketchbook (1964), The Party (1966) and Fornicon (1969) caused great controversy. "But upon discovering his erotic work, the children’s-book community was scandalized. His books were removed from public libraries and his reputation tarnished. Dejected and unable to find work, he left New York in 1971, moving to Nova Scotia with his wife before finding a permanent home in Cork, Ireland." (40)

Primary Sources

(1) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998)

The German regiment was ordered to stop in front of our house. The guns were propped upright nearly in pyramids of three while the unit of young smiling faces broke out, laughing and joking. A horse-drawn field kitchen pulled up, and lunch was served. Fascinated, I went out on the sidewalk, and a beaming soldier offered me a taste of his soup. Then they marched on. They were not the hordes of Huns I had so vividly imagined, and what's more, they seemed nice, even cordial...On the 16th of July all Jews who remained in Alsace were told that they had twenty-four hours to pack a suitcase and enough food for five days. They were allowed 2,000 francs per person, but gold, jewelry, and wedding rings were to be left behind... They were deported to France in convoys... Within six months Colmar was to lose one-third of its population, while shops, houses, furniture, and all assets were confiscated...

Every family was given an Ahnenpass, a kind of passport with one's family tree going back four generations, 'proving' that no Jewish blood had soiled our 'Aryan' blood.

(3) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998)

The common people spoke Alsatian, a German dialect, and had no trouble switching. But I, from a bourgeois background, spoke only French. My brother gave me a crash course, allowing me, three months later, to return to school... It was now obligatory for children to be sent to the local school. All Alsatian teachers were sent to Germany for Umschulung (retraining)... They were replaced by young teachers, some in Wehmacht uniforms... they were easy-going missionaries. In every class hung a portrait of the Führer, and every room was fitted with a Volksender, the word used for radio, on which we listened to Adolf Hitler every time he spoke....

As the teacher entered the class, the students would stand and raise their right arms. The teacher would say, For the Führer a triple victory, answered by a chorus of Heil! three times... Every class started with a song. The almighty Führer would be staring at us from his picture on the wall. These uplifting songs were brilliantly written and composed, transporting us into a state of enthusiastic glee...

The first hour of school was dedicated to history, especially to the rise of the Nazi movement and the lastest news of military victories. "We had a special copybook for this. Indoctrination was daily and systematic. Jazz, modern art, and comic strips were considered degenerate and forbidden. I could easily imagine Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, or Superman and their likes dutifully arrested by the Gestapo to serve in some hard labour squad....

We were promised a reward of money if we denounced our parents or our neighbours - what they said or did... We were told: Even if you denounce your parents, and if you should love them, your real father is the Führer, and being his children you will be the chosen ones, the heroes of the future...

Athletics, gymnastics, swimming, playing, and boxing were priorities. Then came German, history, geography, art, and music; after that biology, chemistry, physics, and math, and last, foreign languages.

(3) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998)

Each day, students showed up with bags containing everything fit to be recycled-papers, rags, tin cans, bottles, bones, boxes, toothpaste tubes, even horse chestnuts - all part of the war effort. In the winter of 1942 in Alsace they collected 3,963,699 old woolen scarves, and 479,589 pairs of old socks! All of these were stored in the huge attic of our school.

Every Saturday afternoon the whole population had to report to the potato fields, with bottles in their hands, to pick potato bugs (Colorado beetles) that had suddenly appeared, which we were told was part of a "Negro Judeo-American" conspiracy to starve the German people.

(4) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998)

In the fall it was back to school, re-renamed Lycee Bartholdi. We were given new blue copybooks - a present from Canada. The janitor would come every day to fill the ink pots on the desks and distribute vitamin cookies. I was to be quickly disillusioned seeing the French making the same mistakes as the Nazis - the entire beautiful school library was emptied and burned in the yard, along with films and everything of German origin. Goethe and Schiller went the same way as Heine and Thomas Mann. Even the plaster busts of Greek and Roman philosophers were smashed...

The changes in school were traumatic for me and my friends. It was forbidden to speak Alsatian or German, and we were punished for every word uttered.... We had a crop of new teachers, some of them French, and others were Alsatians who had chosen to stay in France during the war. For some we were nothing but scum, a brood of collaborators. Alsatian would still be forbidden twenty-five years after the war - a deep blow to our identity...

Our French teacher was a born sadist, a big fat pink toad who wore dark glasses. A necrophiliac, in a trance-like state he would rant on about the beauty of cadavers. When Alsatian students were called up to recite he would grab one of our ears; the moment we stopped reciting he twisted the ear until we were on our knees. The French boys were automatically good students and were not subject to this treatment.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 1

(2) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 315

(3) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 18

(4) William L. Shirer, diary entry (21st June, 1940)

(5) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 31

(6) Michael Burleigh, The Third Reich: A New History (2001) page 465

(7) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 35

(8) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 40

(9) Rebecca Weisner, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005) page 48

(10) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 42

(11) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 46

(12) Fritz Fink, The Jewish Question in Education (1937)

(13) Eric A. Johnson & Karl-Heinz Reuband, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005) page 4

(14) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 50

(15) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 60

(16) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 57

(17) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 58

(18) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) pages 58-59

(19) William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of Nazi Germany (1959) page 317

(20) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 61

(21) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 63

(22) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 64

(23) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 73

(24) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 77

(25) Michael Burleigh, The Third Reich: A New History (2001) page 236

(26) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 78

(27) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 79

(28) Cate Haste, Nazi Women (2001) page 101

(29) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 79

(30) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 93

(31) William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of Nazi Germany (1959) page 894

(32) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 100

(33) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 284

(34) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 127

(35) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 150

(36) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) page 160

(37) Tomi Ungerer, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis (1998) pages 168-171

(38) Sarah Cowan, The Paris Review (30th January, 2015)

(38) Free Library Blog (November, 2010)

(39) Robert Sullivan, The New Yorker (4th February, 2015)

(40) Sarah Cowan, The Paris Review (30th January, 2015)