Rebecca Weisner

Rebecca Weisner was born in Berlin on 11th August, 1926. Both her parents were Orthodox Jews who had been born in Poland. "My first memory is from 1932 or 1933, when I used to go to the park to play with my friends. It was different in Europe in those days. You could go in the street and nobody harmed you. But I did see the Socialist and the Nazi Party fighting and shooting in the streets... I remember shooting going on just below our window. We were on the first floor. My mom kept my brother and me under the window in case a bullet came through." (1)

Adolf Hitler gained power in 1933. Soon afterwards the school curriculum changed. Cate Haste has argued that education in "racial awareness" began at school and children were constantly reminded of their racial duties to the "national community". Biology, along with political education, became compulsory. Children learnt about "worthy" and "unworthy" races, about breeding and hereditary disease. "They measured their heads with tape measures, checked the colour of their eyes and texture of their hair against charts of Aryan or Nordic types, and constructed their own family trees to establish their biological, not historical, ancestry.... They also expanded on the racial inferiority of the Jews". (2)

A Jewish Girl in Berlin

German children were ordered to write essays with titles such as "The Jews are our misfortune". Rebecca Weisner suffered a great deal in her German school: "When I was six, Hitler came to power. I started school in April 1933, just at the same time... There were some German girls I was friends with - we grew up together - and, all of a sudden, one day I come down and they call me dirty Jew. My friends, the friends I grew up with! I couldn't comprehend it. I would say to my mother, Why do they call me dirty? I am not dirty. And she said, You had better get used to it. You're Jewish, and that is what you have to learn. So just take it. But I didn't want to take it. I fought." (3)

In 1933 all Jewish teachers were dismissed from German schools. (4) Members of the Hitler Youth were encouraged to make life difficult for Jewish children in school. Hildegard Koch and her German Girls' League friends began a campaign against the Jewish girls in her class. "The two Jewish girls in our form were racially typical. One was saucy and forward and always knew best about everything. She was ambitious and pushing and had a real Jewish cheek. The other was quiet, cowardly and smarmy and dishonest; she was the other type of Jew, the sly sort. We knew we were right to have nothing to do with either of them. In the end we got what we wanted. We began by chalking 'Jews out!' or 'Jews perish, Germany awake!' on the blackboard before class. Later we openly boycotted them. Of course, they blubbered in their cowardly Jewish way and tried to get sympathy for themselves, but we weren't having any. In the end three other girls and I went to the Headmaster and told him that our Leader would report the matter to the Party authorities unless he removed this stain from the school. The next day the two girls stayed away, which made me very proud of what we had done." (5)

The Minister of the Interior, Wilhelm Frick, outlined the role of education in Nazi Germany: "The purpose of history was to teach people that life was always dominated by struggle, that race and blood were central to everything that happened in the past, present and future, and that leadership determined the fate of peoples. Central themes in the new teaching including courage in battle, sacrifice for a greater cause, boundless admiration for the Leader and hatred of Germany's enemies, the Jews." (6)

Jewish children in German schools suffered terribly from bullying: "The children called me Judenschwein (Jewish pig)... When I came home I was crying and said, What is a Judenschwein? Who am I? I didn't know who I was. I was only a kid. I didn't know what I was, Jew or not Jew. There were many times when I was beaten up coming from school. I remember one teacher who had something against me because I was a Jew in his class. Every time when I must have been unruly, he used to pull me up front and bend me over and whip me with a bamboo stick." (7)

Rebecca Weisner's parents arranged for her to go to a Jewish school: "These Jewish schools were all private... It was a regular school like the German one, but it wasn't German. Every day we had one hour of Hebrew. But everything else was like any other school... The other children were not allowed to play with me. They wouldn't talk to me. They called me names like dirty Jew... We had a German school across the street... So there was a lot of fighting between the two sides." (8)

The Nazi government began an anti-Jewish propaganda campaign. This included the newspaper, Der Stürmer, edited by Julius Streicher. "The Der Stürmer newspaper... was all over the place; it was on every corner, you couldn't miss it. There were the Jews with the big noses and all that. I could not understand that anyone could imagine that Jewish people could look like this."

Life for Jewish people in Nazi Germany was full of restrictions: "We weren't allowed to go swimming anymore (in the swimming pools). Jewish kids were not allowed to mix... Also I remember that there were Christmas displays in one of the big department stores. I used to love it. In 1937 I said to my mother that I wanted to go to see the display. Now my mother was dark blond - she didn't look Jewish. But I was very dark like my father. So she said to me, You can't go there. You look too Jewish. And this gave me another complex - I looked Jewish. I said, Now how am I supposed to look? She said, Well, you are a Jewish kid and you look Jewish, so you can't go there. And then there were the Germans who gave us a lot of trouble. There were so many minor incidents.... We knew we had to accept it and that was it."

Kristallnacht (Crystal Night)

Ernst vom Rath was murdered by Herschel Grynszpan, a young Jewish refugee in Paris on 9th November, 1938. At a meeting of Nazi Party leaders that evening, Joseph Goebbels suggested that night there should be "spontaneous" anti-Jewish riots. (9) Reinhard Heydrich sent urgent guidelines to all police headquarters suggesting how they could start these disturbances. He ordered the destruction of all Jewish places of worship in Germany. Heydrich also gave instructions that the police should not interfere with demonstrations and surrounding buildings must not be damaged when burning synagogues. (10)

These riots became known as Kristallnacht (Crystal Night). On 11th November, 1938, Reinhard Heydrich reported to Hermann Göring, details of the night of terror: "74 Jews killed or seriously injured, 20,000 arrested, 815 shops and 171 homes destroyed, 191 synagogues set on fire; total damage costing 25 million marks, of which over 5 million was for broken glass." (11) It was decided that the "Jews would have to pay for the damage they had provoked. A fine of 1 billion marks was levied for the slaying of Vom Rath, and 6 million marks paid by insurance companies for broken windows was to be given to the state coffers." (12)

It is estimated that around 30,000 Jews were arrested in Germany. This included members of Rebecca Weisner's family: "All the Polish Jews were rounded up and it took something like twenty-four hours to round them up. My father was taken and my brother was taken (he was just sixteen) and my grandfather was taken; my mom and I and my grandmother were left behind. They took them to Poland, but we didn't know that for three days." Rebecca's mother sent her to live with her sister in Stralsund: "In that little city lived about twenty Jewish families, all immigrants from Poland, but all related. I remember well how my mother then put me on the train and my aunt took me off the train and how, at age twelve, I went there and they all were beaten up. They were already beaten up on the streets by the Germans. I don't know how they knew, they were Jewish, but being that it wasn't such a big place, maybe they knew that. They didn't arrest them, but they were beaten up. This happened in every small town in Germany except in Berlin." (13)

Life in a Concentration Camp

Rebecca's father and brother were eventually released and in July 1939 it was decided that the whole family should move to Poland. "We got from the Jewish committee an apartment with a room and a kitchen in a small town in Silesia near Krakow, about half an hour away from Auschwitz by car. I was there when the German army marched in. It was six in the morning when we heard on the radio that the Germans had marched into Poland. By nine o'clock they were in the town. My father's brother was like a big shot in that town. I think it wasn't more than two days that the Germans were there before they arrested him. But he ran away and they sent the dogs after him and they killed him. Every few weeks they rounded up people and shot them." (14)

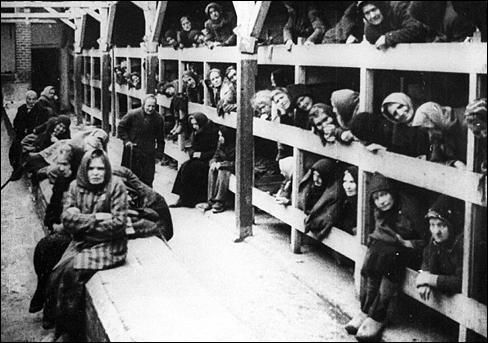

In January 1942, all the Jews in the town were arrested. Rebecca Weisner was sent to a women's camp near Breslau in eastern Germany. "When you got to the camp they took away whatever we had - our watches, clothes, and everything. They shaved our hair. It was tragic. You know, you're a young girl and they shave your head. We didn't get any food anymore. If you asked me what was the worst in the camp for me personally, it was hunger. It was also cold; we didn't have much warmth. We slept in an old factory hall, in bunk beds, up and down in wooden bunks and straw. It was like an outdoor, not an indoor, house, with little holes in the middle."

Later that year, her brother, parents, grandparents and cousins were all taken to Auschwitz, an extermination camp. Over 250,000 people who had been living in Poland died in the camp. It is estimated that as many as 4 million people died in gas ovens and by a variety of other methods at Auschwitz. (15) "Somehow we knew those things were more or less going on that there was Auschwitz and that they had gas ovens to gas all the people, children and so. We knew that... You know, they were young - my mother was forty; my father was forty-four; my brother was just barely twenty - and this was something that I had to live with... I cried for maybe two days because I knew that I was all alone. I only had one brother and I really didn't want to live at that point. I never cried again after that time. Until today, I still cannot cry and I have had a lot of emotional problems because of all those things. I can't cry; I choke, but I can't cry." (16)

In January 1945 the Red Army was approaching Breslau. The authorities decided to take the inmates towards central Germany. "It was the coldest winter in Europe in 1945. We didn't have much clothes or shoes. We had to walk in that cold weather and we had no food after the first few days. If they were in a good mood, they put us in a barn. It wasn't warm, but it was better than the snow. But most of the nights we were outside sitting or whatever-it was so cold! Then I said to myself, I'm not going to make it. I was near the end... There were like three and a half thousand girls. I remember that when the girls sat down, they were shot. They couldn't walk; they would sit down and were shot. So I said to myself, What can I do? I am not going to make it either way, so I'll take a chance. And when we walked by a certain woods, somehow I had the chance to run into the woods. Some girls followed me and they were shooting at us. But instinct told us to hide behind the trees and I guess they gave up on us."

Rebecca Weisner and the other young women who escaped decided their best chance of survival was to walk towards the Russian troops: "The Germans were evacuating east Germany already. They were going west, so we went east. At night we were walking and in the daytime hiding. Then we said, We have to get some food. So we took a chance, and a farmer found us in a barn sleeping. He was nice and gave us food. We had prison clothes on... There was no way we could take our clothes off; it was too cold. Anyway, he gave us some food and said, You can sleep here. But, in the morning, you had better go. Our only hope was to get to the Russians. It took us two weeks, and then we got to the Russians." (17)

Primary Sources

(1) Rebecca Weisner, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

These Jewish schools were all private... It was a regular school like the German one, but it wasn't German. Every day we had one hour of Hebrew. But everything else was like any other school... The other children were not allowed to play with me. They wouldn't talk to me. They called me names like dirty Jew... We had a German school across the street... So there was a lot of fighting between the two sides...

So I started the Jewish school and then things went better for me. But we had a German school across the street and we had a lot of trouble with German Jewish kids. They were always taught that they were better than the Eastern Europeans and they looked at us like we were from Eastern Europe even when we were born in Berlin. So there was a lot of fighting between the two sides. There was a lot of resentment from the German Jewish people.

There are so many incidents. We weren't allowed to go swimming anymore (in the swimming pools). Jewish kids were not allowed to mix, so we never learned to swim really. But we used to go outside of Berlin with the subway and the train and we, by ourselves, went bathing in the Wannsee. And we had only one Jewish sports stadium left. I belonged to a Zionist Jewish organization and we were very into sports; sports kept me going. We had competitions every few months, and in school we had a lot of sports too, indoors and outdoors. So we were always into sports and we had a lot of friends, all Jewish friends, but all from Eastern European backgrounds...

I saw the Sturmer newspaper. It was all over the place; it was on every corner, you couldn't miss it. There were the Jews with the big noses and all that. I could not understand that anybody could imagine that Jewish people could look like this. I guess you could say I was a little angry with that; there was a lot of anger that came out later.

Also I remember that there were Christmas displays in one of the big department stores. I used to love it. In 1937 I said to my mother that I wanted to go to see the display. Now my mother was dark blond-she didn't look Jewish. But I was very dark like my father. So she said to me, "You can't go there. You look too Jewish." And this gave me another complex-I looked Jewish. I said, "Now how am I supposed to look?" She said, "Well, you are a Jewish kid and you look Jewish, so you can't go there." And then there were the Germans who gave us a lot of trouble. There were so many minor incidents.... We knew we had to accept it and that was it.

(2) Rebecca Weisner, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

All the Polish Jews were rounded up and it took something like twenty-four hours to round them up. My father was taken and my brother was taken (he was just sixteen) and my grandfather was taken; my mom and I and my grandmother were left behind. They took them to Poland, but we didn't know that for three days. Now my mother's sister lived in Stralsund, which is near Stettin and Rostock by the Baltic Sea, and I had just been there that summer helping my aunt with her little baby girl. In that little city lived about twenty Jewish families, all immigrants from Poland, but all related. I remember well how my mother then put me on the train and my aunt took me off the train and how, at age twelve, I went there and they all were beaten up. They were already beaten up on the streets by the Germans. I don't know how they knew, they were Jewish, but being that it wasn't such a big place, maybe they knew that. They didn't arrest them, but they were beaten up. This happened in every small town in Germany except in Berlin.

Now, what happened to my father was that he somehow got out of that internment camp on the Polish side of the German border and went to the town where he was born, where he still had sisters and brothers who remained there. And then he called us from there and said that everything would be okay and that we shouldn't worry.

I went to Poland because we had to leave in July 1939. We got from the Jewish committee an apartment with a room and a kitchen in a small town in Silesia near Krakow, about half an hour away from Auschwitz by car. I was there when the German army marched in. It was six in the morning when we heard on the radio that the Germans had marched into Poland. By nine o'clock they were in the town. My father's brother was like a big shot in that town. I think it wasn't more than two days that the Germans were there before they arrested him. But he ran away and they sent the dogs after him and they killed him. Every few weeks they rounded up people and shot them.

That was before they even had camps in Poland. In 1939 I was just thirteen, August 11 was my birthday. I never went to school after that; I had finished just barely the sixth grade in Berlin....One day I was walking down the street with a friend and two German officers from the Nazis stopped their car and said, "I take you with me. You come here." Like a kid with a big mouth, I then said to them in German, "You can't take me. I am too young to go." He gave me right away a slap on the face, a big hard one, and said, "You come with me." And then they took me and the girl who had walked with me into the school. Later on they rounded up a lot of Jewish girls from that town, I think about forty, and we were sent to a transport camp. We were there a few days. It was hard for me there; it was like I couldn't cope with it. It was in January or February 1942.

Then we were sent to a women's camp near Breslau in eastern Germany. At the beginning, we were not too bad off. But sometime in September or October 1942, my brother, my parents, my grandparents, and my cousins were all taken to Auschwitz and nobody ever saw them again....

We already knew by late July, August. One came from this camp, one came from that camp. Somehow we knew those things were more or less going on that there was Auschwitz and that they had gas ovens to gas all the people, children and so. We knew that... You know, they were young-my mother was forty; my father was forty-four; my brother was just barely twenty - and this was something that I had to live with.

I cried for maybe two days because I knew that I was all alone. I only had one brother and I really didn't want to live at that point. I never cried again after that time. Until today, I still cannot cry and I have had a lot of emotional problems because of all those things. I can't cry; I choke, but I can't cry.

(3) Rebecca Weisner, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

When you got to the camp they took away whatever we had - our watches, clothes, and everything. They shaved our hair. It was tragic. You know, you're a young girl and they shave your head. We didn't get any food anymore. If you asked me what was the worst in the camp for me personally, it was hunger. It was also cold; we didn't have much warmth. We slept in an old factory hall, in bunk beds, up and down in wooden bunks and straw. It was like an outdoor, not an indoor, house, with little holes in the middle.

All my life I had to run around in the middle of the night. I still do. Over there, where you were walking, you had people screaming, and people crying, and people praying. It was so weird! It was so frightening! I'm still trying to figure out today how they cleaned it all up. There was no water, no paper. In 1944 it went from bad to worse for us in the camps. We were exhausted. Once I was beaten in the lower back, and I have had to have surgery from that. Twelve years ago I was paralyzed. It was a long story. Also I have had psychological difficulties. I've had psychiatry on and off for twenty years now. I finally gave it up, because it didn't help me. They were not qualified to help a survivor.

(4) Rebecca Weisner, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

It was the coldest winter in Europe in 1945. We didn't have much clothes or shoes. We had to walk in that cold weather and we had no food after the first few days. If they were in a good mood, they put us in a barn. It wasn't warm, but it was better than the snow. But most of the nights we were outside sitting or whatever-it was so cold! Then I said to myself, "I'm not going to make it." I was near the end... There were like three and a half thousand girls. I remember that when the girls sat down, they were shot. They couldn't walk; they would sit down and were shot. So I said to myself, "What can I do? I am not going to make it either way, so I'll take a chance." And when we walked by a certain woods, somehow I had the chance to run into the woods. Some girls followed me and they were shooting at us. But instinct told us to hide behind the trees and I guess they gave up on us.

That was a lucky thing because the Germans were evacuating east Germany already. They were going west, so we went east. At night we were walking and in the daytime hiding. Then we said, "We have to get some food." So we took a chance, and a farmer found us in a barn sleeping. He was nice and gave us food. We had prison clothes on... There was no way we could take our clothes off; it was too cold. Anyway, he gave us some food and said, "You can sleep here. But, in the morning, you had better go." Our only hope was to get to the Russians. It took us two weeks, and then we got to the Russians.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)