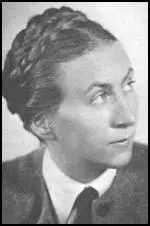

Gertrud Scholtz-Klink

Gertrud Scholtz-Klink was born in Adelsheim, Germany on 9th February, 1902. After leaving school she worked as a nurse in Berlin. She married a postal worker at the age of eighteen. Both of them joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) and he died of a heart-attack at a Nazi Rally. According to a later newspaper report: "Her first husband died and left her with six children. Two of the children died. She worked to bring up the others."

In 1929 Scholtz-Klink, became leader of the women's section in Baden. She was a fine orator and became deputy leader of the National Socialist Frauenschaft. Louis L. Snyder described her as "an able, energetic worker and the mother of four children... and was active in labour organizations."

Scholtz-Klink consistently argued against women becoming involved in politics. She suggested that female members of the German Communist Party (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP) had set a bad example in the Reichstag: "Anyone who has seen the Communist and Social Democratic women scream on the street and the parliament, realize that such an activity is not something which is done by a true woman". She claimed that for a woman to be involved in politics, she would either have to "become like a man", which would "shame her sex".

When Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933 he appointed Scholtz-Klink as Reich Women's Leader and head of the Nazi Women's League. Scholtz-Klink's main task was to promote male superiority and the importance of child-bearing. In one speech she pointed out that: "Woman is entrusted in the life of the nation with a great task, the care of man, soul, body, and mind. It is the mission of woman to minister in the home and in her profession to the needs of life from the first to last moment of man's existence. Her mission in marriage is... comrade, helper and womanly complement of man - this is the right of woman in the New Germany."

Cate Haste, the author of Nazi Women (2001) has pointed out: "Gertrud Scholtz-Klink was thought to have all the qualifications of the Nazi ideal woman. Trim and neat, her blonde hair braided in plaits, without make-up, a kinderreich mother, she proceeded to educate women in their proper duties to the state, transforming women's groups into agents of indoctrination in Nazi ideology." Scholtz-Klink's role was overseen by Hitler's director of national welfare, Erich Hilgenfeldt. He held ultimate responsibility for the direction, policy and activities of the women's organizations. One of the first statements he made after his appointment "was to leave all policy-making to men."

In July 1934 Scholtz-Klink was appointed as head of the Women's Bureau in the German Labour Front. She now had responsibility for persuading women to work for the good of the Nazi government. In August 1933 a law was passed that enabled married couple to obtain loans to set up homes and start families. However, if they accepted this money the woman had to promise not to seek re-employment. To pay for these loans single men and childless couples were taxed more heavily.

The decline in unemployment after the Nazis gained power meant that it was not necessary to force women out of manual work. However, action was taken to reduce the number of women working in the professions. Married women doctors and civil servants were dismissed in 1934 and from June 1936 women could no longer act as judges or public prosecutors. Hitler's hostility to women was shown by his decision to make them ineligible to jury service because he believed them to be unable to "think logically or reason objectively, since they are ruled only by emotion."

Scholtz-Klink was also placed in charge of the Nazi Mother Service. The organization issued a statement explaining its role in Nazi Germany: "The purpose of the National Mother Service is political schooling. Political schooling for the woman is not a transmission of political knowledge, nor the learning of Party programs. Rather, political schooling is shaping to a certain attitude, an attitude that out of inner necessity affirms the measures of the State, takes them into women's life, carries them out and causes them to grow and be further transmitted."

In September 1937 Scholtz-Klink was interviewed by The New York Times. "One meets her surrounded by Nazi flags and uniforms. Her gentle femininity is a startling contrast to the military atmosphere. She is a friendly woman in her middle thirties, blonde, blue-eyed, regular featured, slender. She sits in a wicker chair on her little balcony and chats with her visitor. Her complexion is so fresh and clear that she dares to do without powder or rouge. She talks, and one notes that her own, capable hands have known hard work.... She has had little time for education; her training for her present position came through hard work and party experience... What does she hope to accomplish for German women in the next ten years? She laughs and cannily refuses to commit herself. She turns to the orthodox National Socialist viewpoint when birth control is mentioned, education for women, the old Feminist movement and working women's problems. Does she feel that her hard-won accomplishments for German women will be swept away in another war? Again she will not commit herself."

Traudl Junge argued that many young women were turned off Nazism by the image projected by Scholtz-Klink. "The Führerin Gertrud Scholtz-Klink was the type we did not like at all. She was just bourgeois and she was so ugly and wasn't fashionable at all. So that was why we didn't bother about joining her organization... It didn't touch me or my friends very much... We were interested in dancing and ballet, and I didn't care much for politics." Junge did not like the message that young women should not wear make-up and had to be "naturally beautiful, sporty and healthy, and giving her leader (Hitler) a lot of children."

Hitler's government gradually changed its attitude towards women in the work-force. With the build-up for war, it now needed married women to seek employment in industry. In 1937 it rescinded its stipulation that women qualified for marriage loans only if they undertook not to enter the labour market. Gertrud Scholtz-Klink as Reich Women's Leader, issued a statement that said: "It has always been our chief article of fact that woman's place is in the home - but since the whole of Germany is our home we must serve her wherever we can best do so." In 1938 she argued that "the German woman must work and work, physically and mentally she must renounce luxury and pleasure." However, she admitted in 1938 that she "had not once had the chance to discuss women's affairs in person with the Führer."

In 1940, Scholtz-Klink was married to her third husband SS-Obergruppenführer August Heissmeyer, and made frequent trips to visit women at concentration camps for women at Moringen, Lichtenburg, and Ravensbrück. Her husband was later convicted of war crimes.

Martin Bormann suggested that the army should form women's battalions during the war. Scholtz-Klink was always against the idea of women serving in the army. She argued: "I have sons in the war, I will protect my daughters." Despite her opposition in 1942 women were assigned to military duties as "Female Wehrmacht Auxiliaries". Scholtz-Klink received support from Dr. Jutta Rüdiger, the head of the Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls): "It is out of the question. Our girls can go right up to the front and help them there, and they can go everywhere, but to have a women's battalion with weapons in their hands fighting on their own, that I do not support. It's out of the question. If the Wehrmacht can't win this war, then battalions of women won't help either." Baldur von Schirach said "Well, that's your responsibility". Rüdiger retorted: "Women should give life and not take it. That's why we were born." However, when the Red Army was advancing towards in Berlin in 1945 Rüdiger instructed BDM leaders to learn to use pistols for self-defence.

At the end of the Second World War Sholtz-Klink went into hiding near Tübingen with her husband using the names Heinrich and Maria Stuckebrock. However, on 28th February 1948, the couple were identified and arrested. She was released from prison in 1953. Her book, The Woman in the Third Reich, was published in 1978.

Gertrud Scholtz-Klink died on in in Bebenhausen on 24th March 1999.

Primary Sources

(1) Gertrud Scholtz-Klink, To Be German Is to Be Strong (1936)

The National Socialist movement sees the man and the woman as equal bearers of Germany’s future. It asks, however, for more than in the past: that each should first completely accomplish the tasks that are appropriate to his or her nature.

The woman, besides caring for her own children, should first care for those who need her help as mothers of the nation. This primarily involves thinking about family law and supporting families, youth legislation, and protecting the youth. It also requires thinking about the occupational paths that female youth will follow in the coming years, since some men and women are still unemployed, and some changes in women’s work will therefore be needed. Given our relations with each other, we affirm these temporary measures because we have firm faith that we have the strength to overcome the many present difficulties that our people faces. Our love for our people, however, will never allow these temporary difficulties to cause conflicts only for the sake of conflict, or that they be interpreted by sensation-hungry individuals as a failure of the National Socialist worldview.

We are always being asked if we see everything that has to be done in the area of women’s work. We can only say that each has the right and the opportunity to work with us and to follow the path leading to the resurrection of our people. However, we must sense love and concern, we must see that he comes to us because of a love for his people. Empty intellectual thinking or a superiority complex have never saved a people.

Women, I wish to try briefly to make clear what the deepest calling we women have is: motherhood. In the bad fourteen years between 1918 and 1933, motherhood was often robbed of its deepest meaning and reduced to something superficial, something that was even held in contempt. Instead of a child being seen as the deepest affirmation of the woman and of life, it was seen as a burden, as a sacrifice on the part of the woman. A child was often seen not as a great link to God as the creator of all life, before whom we must bow with folded hands and trembling hearts, but rather very often as the result of a weak mind and as an escape from the great events of life.

Many women were superficially mothers, but they had forgotten to subordinate themselves to the law of life, which sees the affirmation of a child as the answer of the woman to her people, and also her contribution to the right of her people to survive.

Transforming the calling of motherhood to the job of motherhood left children joyless, unhappy, without strength or soul. Devilish forces under the leadership of Marxism attempted to lead German women along this path.

It is therefore our task to awaken once again the sense of the divine, to make the calling to motherhood the way through which the German woman will see her calling to be mother of the nation. She will then not live her life selfishly, but rather in service to her people.

(2) The New York Times (26th September, 1937)

One meets her surrounded by Nazi flags and uniforms. Her gentle femininity is a startling contrast to the military atmosphere. She is a friendly woman in her middle thirties, blonde, blue-eyed, regular featured, slender. She sits in a wicker chair on her little balcony and chats with her visitor. Her complexion is so fresh and clear that she dares to do without powder or rouge. She talks, and one notes that her own, capable hands have known hard work. Her first husband died and left her with six children. Two of the children died. She worked to bring up the others. She married again, this time a doctor. She has had little time for education; her training for her present position came through hard work and party experience.

What does she hope to accomplish for German women in the next ten years? She laughs and cannily refuses to commit herself. She turns to the orthodox National Socialist viewpoint when birth control is mentioned, education for women, the old Feminist movement and working women's problems. Does she feel that her hard-won accomplishments for German women will be swept away in another war? Again she will not commit herself.

A final question. How does she feel about the possibility of Germany's going to war?

She glances up at the swastikas and across at the black boots of the uniformed men beyond the doorway and she turns quickly away to hide the tears in her eyes. "I have sons," she says quietly. Her eyes. "I have sons," she says quietly. Her eyes are as sad as the eyes of many other German mothers who know so well the German Labor Camp motto which says so plainly that sons must "fight" stubbornly and die laughing.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)

The Last Days of Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)