Inge Scholl

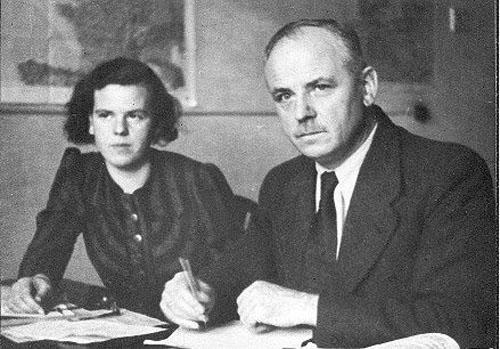

Inge Scholl, the daughter of Robert Scholl and Magdalena Scholl, was born on 11th August, 1917.

Robert Scholl was elected mayor of Forchtenberg. Over the next few years he managed to get the railway extended to the town. He also had a community sports centre built in Forchtenberg but he was considered to be too progressive for some and in 1930 he was voted out of office. (1)

The family moved to Ulm in 1932. "Robert Scholl had lived in several small towns in Swabia, an area of south-west Germany known for its rural charms, thrifty people, and spirit of independence, before settling in Ulm, where he opened his own office as a tax and business consultant. He was a big, rather heavyset man, with strong opinions and an unwillingness, if not an inability, to keep those opinions to himself." (2)

Inge was very close to her sisters and brothers, Hans (b. 1918), Elisabeth (b. 1920), Sophie (b. 1921), Werner (b. 1922) and Thilde (b. 1925). "The Scholl children were seldom seen tumbling about the streets and were never heard singing improper songs in public. A close-knit clan with a strong sense of each other, they usually provided themselves with enough companionship to make a presence of outsiders unnecessary." (3)

Inge Scholl and the German League of Girls

Robert Scholl was a strong opponent of Adolf Hitler and was very upset when Hans joined the Hitler Youth and Sophie Inge and Elisabeth became members of the German League of Girls (BDM) in 1933. He argued against Hitler and the Nazi Party and disagreed with his children's views that he would reduce unemployment: "Have you considered how he's going to manage it? He's expanding the armaments industry, and building barracks. Do you know where that's all going to end... Don't believe them - they are wolves and deceivers, and they are misusing the German people shamefully" (4)

Elisabeth Scholl later pointed out why they rejected their father's advice: "We just dismissed it: he's too old for this stuff, he doesn't understand. My father had a pacifist conviction and he championed that. That certainly played a role in our education. But we were all excited in the Hitler youth in Ulm, sometimes even with the Nazi leadership." (5) Sophie approached BDM with "girlish enthusiasm" but thought it absurd that her Jewish friend, Luise, was not allowed to join. (6)

Inge enjoyed her time in the BDM: "We entered into it with body and soul, and we could not understand why our father did not approve, why he was not happy and proud... Hitler - so we heard on all sides - Hitler would help this fatherland to achieve greatness, fortune, and prosperity. He would see to it that everyone had work and bread. He would not rest until every German was independent, free, and happy in his fatherland. We found this good, and we were willing to do all we could to contribute to the common effort. But there was something else that drew us with mysterious power and swept us along: the closed ranks of marching youth with banners waving, eyes fixed straight ahead, keeping time to drumbeat and song. Was not this sense of fellowship overpowering?"

Inge Scholl particularly enjoyed the outdoor activities: "We went on trips with our comrades in the Hitler Youth and took long hikes through our new land, the Swabian Jura. No matter how long and strenuous a march we made, we were too enthusiastic to admit that we were tired. After all, it was splendid suddenly to find common interests and allegiances with young people whom we might otherwise not have gotten to know at all. We attended evening gatherings in our various homes, listened to readings, sang, played games, or worked at handcrafts. They told us that we must dedicate our lives to a great cause. We were taken seriously - taken seriously in a remarkable way - and that aroused our enthusiasm. We felt we belonged to a large, well-organized body that honored and embraced everyone, from the ten-year-old to the grown man. We sensed that there was a role for us in a historic process, in a movement that was transforming the masses into a Volk. We believed that whatever bored us or gave us a feeling of distaste would disappear of itself." (7)

Robert Scholl held liberal opinions and allowed his children to make their own choices. According to Richard F. Hanser: "They could say whatever they wished, and they all had opinions. This was far from customary practice in German households, where, by long tradition, the authority of the father was seldom questioned or his statements challenged... His aversion to mindless nationalism was not only unchanged but stronger than before. In his dinner-table discussions with his children, he could interpret events for them with an insight unblurred by current prejudices or official pronouncements." (8)

One night, when she was at camp a fifteen-year-old girl said: "Everything would be fine, but this thing about the Jews is something I just can't swallow." The officer in charge tried to explain the passing of the Nuremberg Laws: "The troop leader assured us that Hitler knew what he was doing and that for the sake of the greater good we would have to accept certain difficult and incomprehensible things. But the girl was not satisfied with this answer. Others took her side, and suddenly the attitudes in our varying home backgrounds were reflected in the conversation. We spent a restless night in that tent, but afterwards we were just too tired, and the next day was inexpressibly splendid and filled with new experiences. The conversation of the night before was for the moment forgotten. In our groups there developed a sense of belonging that carried us safely through the difficulties and loneliness of adolescence, or at least gave us that illusion." (9)

Arrest of the Scholl Family

Hans Scholl, was chosen to be the flag bearer when his unit attended the Nuremberg Rally in 1936. Inge Scholl later recalled: "His joy was great. But when he returned, we could not believe our eyes. He looked tired and showed signs of a great disappointment. We did not expect any explanation from him, but gradually we found out that the image and model of the Hitler Youth which had been impressed upon him there was totally different from his own ideal... Hans underwent a remarkable change... This had nothing to do with Father's objections; he was able to close his ears to those. It was something else. The leaders had told him that his songs were not allowed... Why should he be forbidden to sing these songs that were so full of beauty? Merely because they had been created by other races?" (10)

Elisabeth Scholl has argued that during this period all the Scholl children gradually became hostile to the government. They were undoubtedly influenced by the views of their parents but had been disappointed by the reality of living in Nazi Germany: "First, we saw that one could no longer read what one wanted to, or sing certain songs. Then came the racial legislation. Jewish classmates had to leave school." (11)

Hans Scholl and some of his friends decided to form their own youth organization. Inge Scholl later recalled: "The club had its own most impressive style, which had grown up out of the membership itself. The boys recognized one another by their dress, their songs, even their way of talking... For these boys life was a great, splendid adventure, an expedition into an unknown, beckoning world. On weekends they went on hikes, and it was their way, even in bitter cold, to live in a tent... Seated around the campfire they would read aloud to each other or sing, accompanying themselves with guitar, banjo, and balalaika. They collected the folk songs of all peoples and wrote words and music for their own ritual chants and popular songs." (12)

Six months of National Labour Service was followed by conscription into the German Army. Hans always loved horses and he volunteered and was accepted for a cavalry unit in 1937. A few months later he was arrested in his barracks by the Gestapo. Apparently, it had been reported that while living in Ulm he had been taking part in activities that were not part of the Hitler Youth program. Sophie, Inge and Werner Scholl were also arrested. (13)

As Sophie was only sixteen, she was released and allowed to go home the same day. One biographer has pointed out: "She seemed too young and girlish to be a menace to the state, but in releasing her the Gestapo was letting slip a potential enemy with whom it would later have to reckon in a far more serious situation. There is no way of establishing the precise moment when Sophie School decided to become an overt adversary of the National Socialist state. Her decision, when it came, doubtless resulted from the accretion of offences, small and large, against her conception of what was right, moral, and decent. But now something decisive had happened. The state had laid its hands on her and her family, and now there was no longer any possibility of reconciling herself to a system that had already begun to alienate her." (14)

The Gestapo searched the Scholl house and confiscated diaries, journals, poems, essays, folk song collections, and other evidence of being members of an illegal organisation. Inge and Werner were released after a week of confinement. Hans was detained three weeks longer while the Gestapo attempted to persuade him to give damaging information about his friends. Hans was eventually released after his commanding officer had ensured the police that he was a good and loyal soldier. (15)

Inge Scholl later recalled: "We were living in a society where despotism, hate, and lies had become the normal state of affairs. Every day that you were not in jail was like a gift. No one was safe from arrest for the slightest unguarded remark, and some disappeared forever for no better reason... Hidden ears seemed to be listening to everything that was being spoken in Germany. The terror was at your elbow wherever you went." (16)

White Rose Group

Sophie and Hans Scholl both attended the University of Munich. They helped to form the White Rose discussion group. Members included Alexander Schmorell, Jürgen Wittenstein, Christoph Probst, Willi Graf, Traute Lafrenz, Hans Leipelt, Lilo Ramdohr and Gisela Schertling. Inge Scholl, who lived in Ulm, also attended meetings whenever she was in Munich. "There was no set criterion for entry into the group that crystallized around Hans and Sophie Scholl... It was not an organization with rules and a membership list. Yet the group had a distinct identity, a definite personality, and it adhered to standards no less rigid for being undefined and unspoken. These standards involved intelligence, character, and especially political attitude." (17)

The group of friends had discovered a professor at the university who shared their dislike of the Nazi regime. Kurt Huber was Sophie's philosophy teacher. However, medical students also attended his lectures, which "were always packed, because he managed to introduce veiled criticism of the regime into them". (18) The 49 year-old professor, also joined in private discussions with what became known as the White Rose group. Hans told Inge, "though his hair was turning grey, he was one of them". (19)

In June 1942 the White Rose group began producing leaflets. They were typed single-spaced on both sides of a sheet of paper, duplicated, folded into envelopes with neatly typed names and addresses, and mailed as printed matter to people all over Munich. At least a couple of hundred were handed into the Gestapo. It soon became clear that most of the leaflets were received by academics, civil servants, restaurateurs and publicans. A small number were scattered around the University of Munich campus. As a result the authorities immediately suspected that students had produced the leaflets. (20)

The opening paragraph of the first leaflet said: "Nothing is so unworthy of a civilized nation as allowing itself to be "governed" without opposition by an irresponsible clique that has yielded to base instinct. It is certain that today every honest German is ashamed of his government. Who among us has any conception of the dimensions of shame that will befall us and our children when one day the veil has fallen from our eyes and the most horrible of crimes - crimes that infinitely outdistance every human measure-reach the light of day? If the German people are already so corrupted and spiritually crushed that they do not raise a hand, frivolously trusting in a questionable faith in lawful order in history; if they surrender man's highest principle, that which raises him above all other God's creatures, his free will; if they abandon the will to take decisive action and turn the wheel of history and thus subject it to their own rational decision; if they are so devoid of all individuality, have already gone so far along the road toward turning into a spiritless and cowardly mass - then, yes, they deserve their downfall." (21)

According to the historian of the resistance, Joachim Fest, this was a new development in the struggle against Adolf Hitler. "A small group of Munich students were the only protesters who managed to break out of the vicious circle of tactical considerations and other inhibitions. They spoke out vehemently, not only against the regime but also against the moral indolence and numbness of the German people." (22) Peter Hoffmann, the author of The History of German Resistance (1977) claimed they must have been aware that they could do any significant damage to the regime but they "were prepared to sacrifice themselves" in order to register their disapproval of the Nazi government. (23)

In January 1943, the group published a leaflet, entitled A Call to All Germans!, It included the following passage: "Germans! Do you and your children want to suffer the same fate that befell the Jews? Do you want to be judged by the same standards as your traducers? Are we do be forever the nation which is hated and rejected by all mankind? No. Dissociate yourselves from National Socialist gangsterism. Prove by your deeds that you think otherwise. A new war of liberation is about to begin." (24)

The authorities took the fifth leaflet more seriously than the others. One of the Gestapo's most experienced agents, Robert Mohr, was ordered to carry out a full investigation into the group called the "Resistance Movement in Germany". He was told "the leaflets were creating the greatest disturbance at the highest levels of the Party and the State". Mohr was especially concerned by the leaflets simultaneous appearance in widely separated cities. This suggested an organization of considerable size was at work, one with capable leadership and considerable resources. (25)

On 18th February, 1943, Sophie and Hans Scholl went to the University of Munich with a suitcase packed with leaflets. According to Inge Scholl: "They arrived at the university, and since the lecture rooms were to open in a few minutes, they quickly decided to deposit the leaflets in the corridors. Then they disposed of the remainder by letting the sheets fall from the top level of the staircase down into the entrance hall. Relieved, they were about to go, but a pair of eyes had spotted them. It was as if these eyes (they belonged to the building superintendent) had been detached from the being of their owner and turned into automatic spyglasses of the dictatorship. The doors of the building were immediately locked, and the fate of brother and sister was sealed." (26)

Jakob Schmid, a member of the Nazi Party, saw them at the University of Munich, throwing leaflets from a window of the third floor into the courtyard below. He immediately told the Gestapo and they were both arrested. They were searched and the police found a handwritten draft of another leaflet. This they matched to a letter in Scholl's flat that had been signed by Christoph Probst. Following interrogation, they were all charged with treason. (27)

Sophie, Hans and Christoph were not allowed to select a defence lawyer. Inge Scholl claimed that the lawyer assigned by the authorities "was little more than a helpless puppet". Sophie told him: "If my brother is sentenced to die, you musn't let them give me a lighter sentence, for I am exactly as guilty as he." (28)

Sophie was interrogated all night long. She told her cell-mate, Else Gebel, that she denied her "complicity for a long time". But when she was told that the Gestapo had found evidence in her brother's room that proved she was guilty of drafting the leaflet. "Then the two of you knew that all was lost... We will take the blame for everything, so that no other person is put in danger." Sophie made a confession about her own activities but refused to give information about the rest of the group. (29)

Friends of Hans and Sophie had immediately telephoned Robert Scholl with news of the arrests. Robert and Magdalena went to Gestapo headquarters but they were told they were not allowed to visit them in prison over the weekend. They were not told that there trial was to begin on the Monday morning. However, Otl Aicher, Inge Scholl's boyfriend, telephoned them with the news. (30) They were met by Jürgen Wittenstein at the railway station: "We have very little time. The People's Court is in session, and the hearing is already under way. We must prepare ourselves for the worst." (31)

Sophie's parents tried to attend the trial and Magdalene told a guard: "I’m the mother of two of the accused." He responded: "You should have brought them up better." (32) Robert Scholl was forced his way past the guards at the door and managed to get to his children's defence attorney. "Go to the president of the court and tell him that the father is here and he wants to defend his children!" He spoke to Judge Roland Freisler who responded by ordering the Scholl family from the court. The guards dragged them out but at the door Robert was able to shout: "There is a higher justice! They will go down in history!" (33)

Later that day Sophie Scholl, Hans Scholl and Christoph Probst were all found guilty. Judge Freisler told the court: "The accused have by means of leaflets in a time of war called for the sabotage of the war effort and armaments and for the overthrow of the National Socialist way of life of our people, have propagated defeatist ideas, and have most vulgarly defamed the Führer, thereby giving aid to the enemy of the Reich and weakening the armed security of the nation. On this account they are to be punished by death. Their honour and rights as citizens are forfeited for all time." (34)

Robert and Magdalena managed to see their children before they were executed. Inge Scholl later explained what happened: "First Hans was brought out. He wore a prison uniform, he walked upright and briskly, and he allowed nothing in the circumstances to becloud his spirit. His face was thin and drawn, as if after a difficult struggle, but now it beamed radiantly. He bent lovingly over the barrier and took his parents' hands... Then Hans asked them to take his greetings to all his friends. When at the end he mentioned one further name, a tear ran down his face; he bent low so that no one would see. And then he went out, without the slightest show of fear, borne along by a profound inner strength." (35)

Magdalena Scholl said to her 22 year-old daughter: "I'll never see you come through the door again." Sophie replied, "Oh mother, after all, it's only a few years' more life I'll miss." Sophie told her parents she and Hans were pleased and proud that they had betrayed no one, that they had taken all the responsibility on themselves. (36)

Else Gebel shared Sophie Scholl's cell and recorded her last words before being taken away to be executed. "How can we expect righteousness to prevail when there is hardly anyone willing to give himself up individually to a righteous cause.... It is such a splendid sunny day, and I have to go. But how many have to die on the battlefield in these days, how many young, promising lives. What does my death matter if by our acts thousands are warned and alerted. Among the student body there will certainly be a revolt." (37)

They were all beheaded by guillotine in Stadelheim Prison only a few hours after being found guilty. A prison guard later reported: "They bore themselves with marvelous bravery. The whole prison was impressed by them. That is why we risked bringing the three of them together once more-at the last moment before the execution. If our action had become known, the consequences for us would have been serious. We wanted to let them have a cigarette together before the end. It was just a few minutes that they had, but I believe that it meant a great deal to them." (38)

A few days after Sophie and Hans were executed, Robert and Magdalena Scholl and their children, Inge and Elisabeth were arrested. (39) They were put into solitary confinement and Inge came down with diphtheria. In August 1943, they were tried and although Robert received a two-year sentence, the women were found not guilty. (40) Elisabeth later recalled: "We were outcasts. Many of my father's clients - he was a tax accountant - wanted to have nothing more to do with the family. It was always nothing personal - just because of the business. Passers-by took to the other side of the road." (41)

Werner Scholl went missing in 1944 while fighting in the Soviet Union. Although his body was never found it is assumed he was killed in action. (42)

After the war Inge married Otl Aicher. After the war Inge and Otl founded a school in the city of Ulm for adult education. Inge was head of the school from 1946 to 1974. They had five children, Eva, Florian, Julian and Manuel; another child, Pia, died in a car accident in 1975. (43)

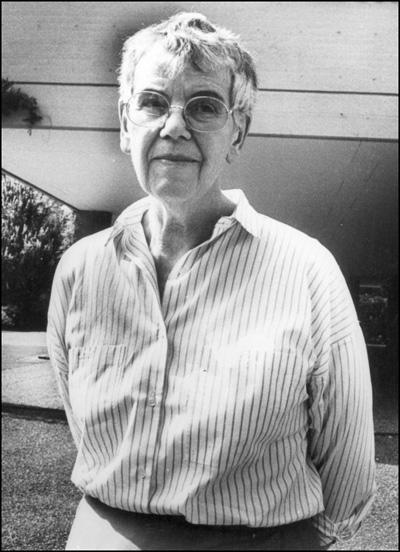

She also wrote a book about the White Rose group, Students Against Tyranny (1952), later republished as The White Rose: 1942-1943 (1983). Edmund L. Andrews, later pointed out: "The book and subsequent writing by Mrs. Aicher-Scholl influenced many Germans who grew up after the war, reinforcing what was already a deep revulsion against the militarism that had brought the country to catastrophe and moral disgrace".(44)

In the 1980s Inge Aicher-Scholl was a leading figure in the German peace movement and was heavily involved in the campaign against the stationing of US nuclear missiles in Germany. In 1985 she was arrested for taking part in a sit-in at the American Pershing II missile base in Mutlangen. (45)

Inge Aicher-Scholl died of cancer at her home in Leutkirch on 4th September, 1998.

Primary Sources

(1) Inge Scholl, The White Rose: 1942-1943 (1983)

One morning I heard a girl tell another on the steps of the school, "Now Hitler has taken over the government." The radio and newspapers promised, "Now there will be better times in Germany. Hitler is at the helm."

For the first time politics had come into our lives. Hans was fifteen at the time, Sophie was twelve. We heard much oratory about the fatherland, comradeship, unity of the Volk, and love of country. This was impressive, and we listened closely when we heard such talk in school and on the street. For we loved our land dearly - the woods, the river, the old gray stone fences running along the steep slopes between orchards and vineyards. We sniffed the odor of moss, damp earth, and sweet apples whenever we thought of our homeland. Every inch of it was familiar and dear. Our fatherland - what was it but the extended home of all those who shared a language and belonged to one people. We loved it, though we couldn't say why. After all, up to now we hadn't talked very much about it. But now these things were being written across the sky in flaming letters. And Hitler - so we heard on all sides - Hitler would help this fatherland to achieve greatness, fortune, and prosperity. He would see to it that everyone had work and bread. He would not rest until every German was independent, free, and happy in his fatherland. We found this good, and we were willing to do all we could to contribute to the common effort. But there was something else that drew us with mysterious power and swept us along: the closed ranks of marching youth with banners waving, eyes fixed straight ahead, keeping time to drumbeat and song. Was not this sense of fellowship overpowering? It is not surprising that all of us, Hans and Sophie and the others, joined the Hitler Youth.

We entered into it with body and soul, and we could not understand why our father did not approve, why he was not happy and proud. On the contrary, he was quite displeased with us; at times he would say, "Don't believe them - they are wolves and deceivers, and they are misusing the German people shamefully." Sometimes he would compare Hitler to the Pied Piper of Hamelin, who with his flute led the children to destruction. But Father's words were spoken to the wind, and his attempts to restrain us were of no avail against our youthful enthusiasm.

We went on trips with our comrades in the Hitler Youth and took long hikes through our new land, the Swabian Jura. No matter how long and strenuous a march we made, we were too enthusiastic to admit that we were tired. After all, it was splendid suddenly to find common interests and allegiances with young people whom we might otherwise not have gotten to know at all. We attended evening gatherings in our various homes, listened to readings, sang, played games, or worked at handcrafts. They told us that we must dedicate our lives to a great cause. We were taken seriously - taken seriously in a remarkable way - and that aroused our enthusiasm. We felt we belonged to a large, well-organized body that honored and embraced everyone, from the ten-year-old to the grown man. We sensed that there was a role for us in a historic process, in a movement that was transforming the masses into a Volk. We believed that whatever bored us or gave us a feeling of distaste would disappear of itself. One night, as we lay under the wide starry sky after a long cycling tour, a friend - a fifteen-year-old girl - said quite suddenly and out of the blue, "Everything would be fine, but this thing about the Jews is something I just can't swallow." The troop leader assured us that Hitler knew what he was doing and that for the sake of the greater good we would have to accept certain difficult and incomprehensible things. But the girl was not satisfied with this answer. Others took her side, and suddenly the attitudes in our varying home backgrounds were reflected in the conversation. We spent a restless night in that tent, but afterwards we were just too tired, and the next day was inexpressibly splendid and filled with new experiences. The conversation of the night before was for the moment forgotten. In our groups there developed a sense of belonging that carried us safely through the difficulties and loneliness of adolescence, or at least gave us that illusion.

(2) Inge Scholl, The White Rose: Students Against Tyranny (1952)

What the circle of the White Rose strove for was increasing public consciousness of the real nature and actual situation of National Socialism. They wanted to encourage passive resistance among wide circles of the populace. In the circumstances, a tight, closely knit organization would not have succeeded. The panicked fear of the people in the face of the constant threat of Gestapo intervention and the ubiquity and thoroughness of the surveillance system were the strongest obstacles. On the other hand, it still seemed possible, by means of anonymous dissemination of information, to create the impression that the Führer no longer enjoyed solid support and that there was general ferment.

(3) Newsday Magazine (6th September, 1998)

Inge Aicher-Scholl, 81, a champion of nonviolence whose siblings were murdered by the Nazis in 1943, died in Germany Friday of complications from cancer. A tireless teacher and spokeswoman against violence, Mrs. Aicher-Scholl wrote several books on an anti-Nazi student group in Munich known as the "White Rose," which was led by her siblings, Hans and Sophie Scholl. After the Nazis murdered the two, they also jailed Mrs. Aicher-Scholl, her parents and her other sister for several months. After the war, Mrs. Aicher-Scholl and some friends, including her future husband, designer Otl Aicher, founded a school in the city of Ulm for adult education and art. Mrs. Aicher-Scholl headed the school from 1946 to 1974. In the 1980s, she gained notoriety through her work in the peace movement, resisting the stationing of U.S. nuclear missiles in Germany. In 1985, she was arrested for taking part in a sit-in at the American Pershing II missile base at the southern town of Mutlangen.

(4) Edmund L. Andrews, New York Times (6th September, 1998)

Inge Aicher-Scholl, who inspired a generation of pacifists in post-World War II Germany by writing about an anti-Nazi youth movement and the killing of her brother and sister, died on Friday. She was 81, and suffered from cancer.

Mrs. Aicher-Scholl moved millions of Germans toward nonviolence by chronicling the activities of the White Rose, a student movement whose leaders included her younger brother and sister, Hans and Sophie Scholl.

Both siblings were killed by Nazis on Feb. 22, 1943, and their parents were imprisoned by Nazi authorities for several months.

In 1952 Mrs. Aicher-Scholl published a book describing White Rose's nonviolent resistance to the Third Reich and its brutal repression by the Nazis. Written in spare and dispassionate prose, the slim volume became a classic work of literature about the Third Reich.

Hans and Sophie Scholl ''came to represent not just the small band of youthful dissenters but all the pacifist sympathizers who were tracked by the Gestapo and the innumerable anonymous victims who were forced to pay the price for believing that human rights were more important than obedience to arbitrary laws,'' wrote Albert von Schirndung, a cultural critic for the Munich daily Suddeutsche Zeitung.

The book's lack of pretension and its description of ordinary Germans lent it power. ''It would have been wrong to create new heroes,'' Mr. Schirndung wrote. ''One had already had enough of heroes. The characters in 'White Rose' were people one could identify with.''

The book and subsequent writing by Mrs. Aicher-Scholl influenced many Germans who grew up after the war, reinforcing what was already a deep revulsion against the militarism that had brought the country to catastrophe and moral disgrace.

In 1946 Mrs. Aicher-Scholl and several friends founded a school for adult education and art in Ulm. One of the co-founders was her future husband, designer Otl Aicher. Mrs. Aicher-Scholl headed the school from 1946 to 1974, and remained active in Germany's peace movement throughout her life.

In the 1980's, she was a prominent figure in anti-military movements that bitterly but unsuccessfully opposed plans by the German government and NATO to station nuclear missiles in West Germany.

In 1985 she was arrested for taking part in a sit-in at the American Pershing II missile base at the southern town of Mutlangen. She and other protesters were charged with disrupting public order and given suspended fines.

Mrs. Aicher-Scholl, who died at home in Leutkirch, in southern Germany, is survived by four of her five children, Eva, Florian, Julian and Manuel; another child, Pia, died in a car accident in 1975, and her husband died in 1991.

Student Activities

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)