Erich Dressler

Erich Dressler was born in Steglitz, a suburb to the south of Berlin, Germany, in 1924. His father was an executive at the Reichsbank. His mother had been married to an army captain who had been killed in the First World War. "Mother hadn't had an easy time of it during the inflation years when her small pension of less than 200 marks a month became practically valueless. The Weimar Republic never did anything for the families of those who fell in the World War, and so she had to help herself as best she could. At first she was a shorthand typist and later became manageress of a laundry... So when she married my father in 1923 it was probably because she didn't want to go on demeaning herself." (1)

Erich Dressler and the Hitler Youth

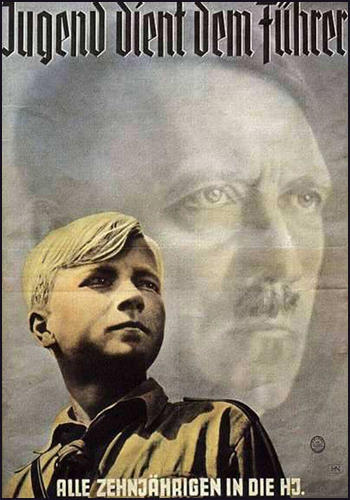

Dressler joined the Jungvolk (for boys aged ten to fourteen) when a branch was started in Steglitz in 1935. "I first heard about this from a schoolfellow who wanted me to join. I was very keen but I did not dare to say anything about it at home, for I knew my father would do all he could to stop me... He used to say the most shocking things about the Führer. So I did not tell him about the Jungvolk, but I joined it all the same - and with it began for me the greatest experience of my life.... We had group meetings with community singing, story-telling and reading. And whatever was read to us was well-chosen. It was invariably picked from German history, and it is only proper, most of it was about the many great soldiers which our nation has produced. (2)

Erich Dressler played an active role in getting rid of teachers he considered to be opponents of the Nazi Party: "In 1934, when I had reached the age of ten, I was sent to the Paulsen Realgymnasium. This was still a regular old-fashioned place with masters in long beards who were completely out of sympathy with the new era. Again and again we noticed that they had little understanding for the Führer's maxim - the training of character comes before the training of intellect.They still expected us to know as much as the pupils used to under the Jewish Weimar Republic, and they pestered us with all sorts of Latin and Greek nonsense instead of teaching us things that might be useful later on. This brought about an absurd state of affairs in which we, the boys, had to instruct our masters. Already we were set aflame by the idea of the New Germany, and were resolved not to be influenced by their outdated ideas and theories, and flatly told our masters so. Of course they said nothing, because I think they were a bit afraid of us, but they didn't do anything about changing their methods of teaching."

It was decided to get rid of the Latin teacher. "Our Latin master set us an interminable extract from Caesar for translation. We just did not do it, and excused ourselves by saying that we had been on duty for the Hitler Youth during the afternoon. Once one of the old birds got up courage to say something in protest. This was immediately reported to our Group Leader who went off to see the headmaster and got the master dismissed. He was only sixteen, but as a leader in the Hider Youth he could not allow such obstructionism to hinder us in the performance of duties which were much more important than our school work.... Gradually the new ideas permeated the whole of our school. A few young masters arrived who understood us and who themselves were ardent national socialists. And they taught us subjects into which the national revolution had infused a new spirit. One of them took us for history; another for racial theory and sport. Previously we had been pestered with the old Romans and such like; but now we learned to see things with different eyes. I had never thought much about being well educated; but a German man must know something about the history of his own people so as to avoid repeating the mistakes made by former generations." (3)

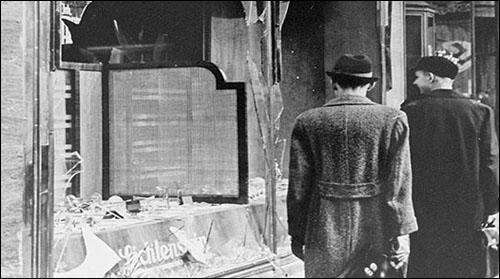

Erich Dressler took part in what became known as Kristallnacht (Crystal Night) in Berlin. "Of course, following the rise of our new ideology, international Jewry was boiling, with rage and it was perhaps not surprising that, in November, 1938, one of them took his vengeance on a counsellor of the German Legation in Paris. The consequence of this foul murder was a wave of indignation in Germany. Jewish shops were boycotted and smashed and the synagogues, the cradles of the infamous Jewish doctrines, went up in flames. These measures were by no means as spontaneous as they appeared. On the night the murder was announced in Berlin I was busy at our headquarters. Although it was very late the entire leadership staff were there in assembly, the Bann Leader and about two dozen others, of all ranks.... I had no idea what it was all about, and was thrilled to learn that were to go into action that very night. Dressed in civilian clothes we were to demolish the Jewish shops in our district for which we had a list supplied by the Gau headquarters of the NSKK, who were also in civilian clothes. We were to concentrate on the shops. Cases of serious resistance on the part of the Jews were to be dealt with by the SA men who would also attend to the synagogues." (4)

An important aspect of the role of the Hitler Youth was military training. Erich Dressler later explained: "We used to carry out regular military exercises in the woods around Berlin, and we always thought this the high spot of our duties... War veterans from an SA detachment came along to direct our operations. We were given real strategic tasks, like the defence of a hill or a road crossing, and we soon learned how to read ordnance maps and work out compass directions." (5)

Dressler met Adolf Hitler in March 1939. "It was a gloriously bright and warm day in March and about a hundred of us were marching along the high road leading to the Berghof, when three large motor cars approached from behind us. The sub-Bann Leader, who was marching at our head, ordered us to step to the side of the road. Suddenly there were feverish shouts from the end of the column. The boys had recognized the Führer's standard on the first car. We all stiffened to attention like one man and raised our arms in the German salute. The leading car slowed and halted. The car following also pulled up... I saw him there for the first and the last time. I noticed that his face was more wrinkled and his hair greyer than one could tell from his photographs. And he had a strange nervous twitch in his face when he spoke. But the most marvellous thing was his eyes; they were very large and radiant, with a peculiar gleam lighting them with an uncanny power. I had to summon all my strength to look into his eyes. But then I knew surely and certainly and calmly that whoever looked in his eyes would be ready to die for him. From that day I knew that the Führer possessed supernatural powers over men. His look was like an electrical discharge, an impelling force which none could withstand. I have read the same thing about Napoleon, but who was he to compare with the man whom destiny had sent to re-design the face of the earth! In my view the Führer was the greatest man of all time."

Hitler spoke a few words to some of those nearest him, asked where they came from, whether they had enough to eat, and what their accommodation was like, and then he shook hands with them. "His voice was strangely subdued and a little hoarse, but very full and masculine." Then he turned towards Dressler."What career have you chosen for yourself?" " I could not speak properly, my throat was tight and throbbing. Officer, was all I could say.The Führer nodded, looked at me silently for a moment, and then said, Very good and pressed my hand. After this he spoke to a few others, but I heard nothing of it. I was as though in a trance. In the end he made an adjutant give our Bann Leader 500 marks, with which we should go and see Vienna. He returned to his car; we stood taut and shouted Heil! until the car was out of sight. The memory of this day has never faded and will be with me all my life. From this time I set myself religiously to follow the maxims which Adolf Hitler had laid down." (6)

The Second World War

Dressler admitted that he had mixed feelings about the early success of the German Army at the beginning of the Second World War. "I was not entirely happy about our lightning victories. I was fifteen and my most ardent desire was to be a soldier myself and to be allowed to fight. But everything went off with such maddening speed, and before I could think of it the Polish campaign was over and the enemy utterly beaten! What was to follow? It was quite clear to me that the war would be over before my time came. At that rate we could have conquered half the globe before I reached the age of eighteen and could join in." (7)

At seventeen he received his army training and joined the Fifth Tank Regiment in 1942. Except for the officers, nearly all the rest of men were teenagers. He first saw action in Sicily in July, 1943. He went into battle against the British Army just outside of Palermo. "We shot up nine or ten of their tanks. Then they were on us. The tanks stopped, and the infantry went forward. We were in utter chaos; there was no communication with our base, our lieutenant was killed, the sergeant-major had lost his head." (8)

What was left of his tank regiment were forced to retreat back to Italy. In September 1943 took part in the Battle of Salerno. "Now we learnt the whole extent of Italian cowardice. They swarmed over to the Americans in whole battalions, leaving tanks which were still intact, throwing down helmets and arms... They fled as soon as they had a chance. Our evacuation turned into a rout. The enemy forces were far too superior. On the retreat our gun jammed and I had to get out of the machine to try to fix it. I was just climbing back when I was hit in the leg." (9)

Erich Dressler was taken back to Germany on a hospital ship. After treatment in an hospital in the Black Forest he was allowed six weeks leave in Berlin: "I found that my parents had aged. Father especially was very sickly and I cannot say that they displayed any marked enthusiasm for the war. As soon as Berlin had received its first heavy air attacks their belief in ultimate victory just faded away. During my stay with them, in November 1943, the British made their dastardly and cowardly attacks on the city without regard for the defenceless women and children." (10)

In January 1944, Dressler was sent to a military academy at Rennes. "Of course none of us gave the war up for lost. We all waited confidently for the wonder weapons of which we had been told." In June, Dressler and the other German soldiers in the area were ordered to Normandy to deal with the D-Day landings. "Most of the men in my unit were youngsters of eighteen to twenty-two years, just come from Italy, who had seen at most a fortnight's action. Having been hustled all across France by train for several days they were fit for nothing, and we went straight into battle." (11)

After being soundly beaten the German Army retreated back into central France. Dressler and some of his friends managed to steal a car and managed to get to Strasburg. He was then taken back to Berlin where he joined the Second Tank Regiment and was ordered to take on the Red Army on the Eastern Front in the Soviet Union. "We had 40 tanks and 40 88mm guns... We surprised a Russian artillery position and completely liquidated it, but then the Russians fought like robots... Russian tanks and mobile tanks and mobile guns lumbered into position and a terrific barrage was opened... We were in complete disorder. Within a few minutes the greater number of our tanks was on fire. We got a hit in the turret which smashed our commander's skull like a squashed orange." (12)

Erich Dressler was once again forced into retreat. In eight days his tank was able to cover about 400 kilometres. "Somehow the fighting spirit had left me. It was not only the continuous retreating, but even more that there was never a respite, and there did not seem to be any plan or pattern which could give us hope of ever advancing again. We just kept on the move incessantly, fighting the Russians when they came too close, but always back and back." (13)

At the beginning of April 1945, Dressler was wounded and taken to a hospital in Prague. With news that Russian forces had entered Czechoslovakia he managed to steal a large Mercedes and headed back to his home in Steglitz. "When I reached our house in Steglitz, I found only a heap of rubble. The neighbours told me that my parents were still underneath. I got two men to help me and we started digging. After six days we found the unrecognisable shape of the body of an elderly woman. On the eighth day I found my father. I knew his clothes, and his spectacles were still grotesquely perched where his nose must have been.The woman may have been my mother. Anyway I buried them together in the corner of the park." (14)

Primary Sources

(1) Erich Dressler, Nine Lives Under the Nazis (2011)

In 1938 I was transferred to the Hitler Youth. I had been a Jungenschafts Leader in the Jungvolk, but now I had to start again as an ordinary Hitler Youth. This made me all the more ambitious, for I knew that I had a gift for leadership in me, and I wanted to advance rapidly. I had long been interested in all technical matters, and I reported to the motorised Hitler Youth, Bann 200 in Steglitz. Later I intended to join tile Wehrmacht in a Panzer regiment. The best preparation for this was service with the motorised HJ, where we were instructed in everything to do with motors, and trained to ride motorcycles.We were trained by men of the NSKK (Nazi Automobile Association). The time of games with the Jungvolk had come to an end. Now we were in earnest.

Our training was more thorough than that given to the ordinary Hitler Jugeud. We learned not only the mechanical side but also to shoot with small-calibre guns, and with army pistols. Our exercises now turned into serious manoeuvres, and all the time we were waiting for the real thing which we called Plan X. On one occasion we really went into action - a planned offensive against Jewry.

Of course, following the rise of our new ideology, international Jewry was boiling, with rage and it was perhaps not surprising that, in November, 1938, one of them took his vengeance on a counsellor of the German Legation in Paris. The consequence of this foul murder was a wave of indignation in Germany. Jewish shops were boycotted and smashed and the synagogues, the cradles of the infamous Jewish doctrines, went up in flames.

These measures were by no means as spontaneous as they appeared. On the night the murder was announced in Berlin I was busy at our headquarters. Although it was very late the entire leadership staff were there in assembly, the Bann Leader and about two dozen others, of all ranks.

I was told that an important confidential discussion was in progress. In the corridor the sub-Bann Leader called me and asked how old I was. Then he said: "Well, you're a bit young still, but you'd better come all the same: Come with me."

I had no idea what it was all about, and was thrilled to learn that were to go into action that very night. Dressed in civilian clothes we were to demolish the Jewish shops in our district for which we had a list supplied by the Gau headquarters of the NSKK, who were also in civilian clothes. We were to concentrate on the shops. Cases of serious resistance on the part of the Jews were to be dealt with by the SA men who would also attend to the synagogues.

But there was little resistance. We carried out our orders in competent military fashion. We went in groups of up to twelve men with clubs to break the shop windows. And the night was full of the music of smashed and splintering glass, and the chorus of our Anti Jewish songs "I am a Jew, do you know my nose," and "Ikey Moses has the dough." Only one Jew, the proprietor of a large lingerie store, dared to turn out in his nightgown and start caterwauling; but he didn't stay there long! Or rather, he did stay there but he didn't caterwaul for long.

One thing seriously perturbed me. All these measures had to be ordered from above. There was no sign of healthy indignation or rage amongst the average Germans. It is undoubtedly a commendable German virtue to keep one's feelings under control and not just to hit out as one pleases; but where the guilt of the Jews for this cowardly murder was obvious and proved, the people might well have shown a little more spirit. This should have been a test case, calling for firm and decided action. Nothing of the kind was done. The Jews were let off with a punitive levy; only a few of them were put in a concentration camp, the rest were tamely allowed to emigrate. I felt the whole thing to be rather an unsatisfactory expression of National Socialist ideals.

(2) Erich Dressler, Nine Lives Under the Nazis (2011)

In 1934, when I had reached the age of ten, I was sent to the Paulsen Realgymnasium. This was still a regular old-fashioned place with masters in long beards who were completely out of sympathy with the new era. Again and again we noticed that they had little understanding for the Führer's maxim - the training of character comes before the training of intellect.They still expected us to know as much as the pupils used to under the Jewish Weimar Republic, and they pestered us with all sorts of Latin and Greek nonsense instead of teaching us things that might be useful later on.

This brought about an absurd state of affairs in which we, the boys, had to instruct our masters. Already we were set aflame by the idea of the New Germany, and were resolved not to be influenced by their outdated ideas and theories, and flatly told our masters so. Of course they said nothing, because I think they were a bit afraid of us, but they didn't do anything about changing their methods of teaching. We were thus forced to "defend" ourselves.

This was rather simple. Our Latin master set us an interminable extract from Caesar for translation.We just did not do it, and excused ourselves by saying that we had been on duty for the Hitler Youth during the afternoon. Once one of the old birds got up courage to say something in protest. This was immediately reported to our Group Leader who went off to see the headmaster and got the master dismissed. He was only sixteen, but as a leader in the Hider Youth he could not allow such obstructionism to hinder us in the performance of duties which were much more important than our school work. From that day onwards the question of homework was settled. Whenever we did not want to do it we were simply "on duty," and no one dared to say any more about it.

Gradually the new ideas permeated the whole of our school. A few young masters arrived who understood us and who themselves were ardent national socialists. And they taught us subjects into which the national revolution had infused a new spirit. One of them took us for history; another for racial theory and sport. Previously we had been pestered with the old Romans and such like; but now we learned to see things with different eyes. I had never thought much about being "well educated"; but a German man must know something about the history of his own people so as to avoid repeating the mistakes made by former generations.

Gradually, one after the other of the old masters was weeded out.The new masters who replaced them were young men loyal to the Führer. The new spirit had come to stay.We obeyed orders and we acknowledged the leadership principle, because we wanted to and because we liked it. Discipline is necessary, and young men must learn to obey.

(3) Erich Dressler, Nine Lives Under the Nazis (2011)

But my disappointment at our molly-coddling of the Jews was soon forgotten in the greatest and most joyful event of my life. In the spring of 1939 I met Adolf Hitler personally - face to face. It was a lucky accident - perhaps more than that. I think it must have been my destiny once in my life to see my Führer and speak to him.

It happened when a mixed group of my H.J. Bann went for a journey through Bavaria and the lower reaches of the Danube, in the course of which we had to pass through Berchtesgaden. Of course we were all wildly excited by the chance to have a look at the Berghof of the Führer. We had absolutely no idea that he was at Berchtesgaden himself, for, according to the papers, he was in Berlin at that time.

It was a gloriously bright and warm day in March and about a hundred of us were marching along the high road leading to the Berghof, when three large motor cars approached from behind us. The sub-Bann Leader, who was marching at our head, ordered us to step to the side of the road. Suddenly there were feverish shouts from the end of the column. The boys had recognized the Führer's standard on the first car. We all stiffened to attention like one man and raised our arms in the German salute.

The leading car slowed and halted. The car following also pulled up. Out of the corner of my eye I saw an adjutant call our Bann Leader over to the first car and he spoke to the figure inside. Suddenly our wild joy and excitement got the better of our discipline. We broke formation with a wild shout and swarmed round the car. The sub-Bann Leader and the Leader were shouting at us, but the Führer and the SS officer laughed, and then he got out of the car.

I saw him there for the first and the last time. I noticed that his face was more wrinkled and his hair greyer than one could tell from his photographs.And he had a strange nervous twitch in his face when he spoke. But the most marvellous thing was his eyes; they were very large and radiant, with a peculiar gleam lighting them with an uncanny power. I had to summon all my strength to look into his eyes. But then I knew surely and certainly and calmly that whoever looked in his eyes would be ready to die for him.

From that day I knew that the Führer possessed supernatural powers over men. His look was like an electrical discharge, an impelling force which none could withstand. I have read the same thing about Napoleon, but who was he to compare with the man whom destiny had sent to re-design the face of the earth! In my view the Führer was the greatest man of all time.

He spoke a few words to some of those nearest him, asked where they came from, whether they had enough to eat, and what their accommodation was like, and then he shook hands with them. His voice was strangely subdued and a little hoarse, but very full and masculine.Then he turned towards me.

"What career have you chosen for yourself?"

I could not speak properly, my throat was tight and throbbing.

"Officer," was all I could say.The Führer nodded, looked at me silently for a moment, and then said, "Very good" and pressed my hand. After this he spoke to a few others, but I heard nothing of it. I was as though in a trance. In the end he made an adjutant give our Bann Leader 500 marks, with which we should go and see Vienna. He returned to his car; we stood taut and shouted "Heil!" until the car was out of sight. The memory of this day has never faded and will be with me all my life. From this time I set myself religiously to follow the maxims which Adolf Hitler had laid down, especially his dictum "Youth must be led by youth."

But the harder I tried to realise the Führer s ideas the more I noticed the resistance of the members of the Hitler Youth. In a district like Steglitz, which was largely inhabited by small officials and shopkeepers, most of the boys had a secondary school education and should have been leaders in the Hitler Youth. But this was not the case. The leaders were drawn from pupils of elementary schools who were now training for jobs or had become workmen or were just full-time members of the Hitler Youth. These boys worked off their inferiority complexes by favouring the apprentices and young labourers of our group, while making sneering jokes about the "`high school men." They used to call us in front of the whole group "la-di-da gents... velvet boys with polished finger nails... you Latin twerps" and so on. And these boors were not able to say a single German sentence correctly.

(4) Erich Dressler, Nine Lives Under the Nazis (2011)

I set off in a northerly direction. On the way I found rhubarb in gardens, which I ate.When day came I lay low in some deserted outbuildings of a farm and the next night continued my journey with two turnips, the only food between me and starvation. In my exhausted state I nearly ran into a Czech patrol, but managed to fall into a ditch and lie there unnoticed. On the fourth night I reached the Elbe. There was no bridge left, and I had to swim against a fiendishly strong current. On the other side I found some clothes in a deserted village and also had a chance to wash and shave. And then at a street crossing I ran directly into a Russian lorry convoy.

I had been afraid that they would take me prisoner, but the officer merely asked me in halting German whether I knew the way to Cottbuss. I had not the faintest notion but I said "Yes, of course," and so they took me with them. After a few stray attempts we really did hit on the right road and just outside Cottbuss I managed to jump off the lorry and escape in the darkness. I made a wide detour round the town and during the night sheltered with a German family, who lived in a cottage on the outskirts.

I now awaited an opportunity of getting to Berlin and at length managed to hide myself on a coal train. After 24 hours we had only got as far as Grunau, but after that I had no further difficulties.

Up to now, the continual danger and nervous strain had left me hardly a minute for reflection. But now, on my return to Berlin, my mind suddenly relaxed into a black and numbing despair. Germany, our greater Germany, was beaten. The Führer dead, most of the other generals and leaders taken prisoner. The Wehrmacht had ceased to exist. Berlin was under the whip of the Bolsheviks and their Jewish commissars. It was all over. Now there was nothing but myself to consider.

When I reached our house in Steglitz, I found only a heap of rubble. The neighbours told me that my parents were still underneath. I got two men to help me and we started digging. After six days we found the unrecognisable shape of the body of an elderly woman. On the eighth day I found my father. I knew his clothes, and his spectacles were still grotesquely perched where his nose must have been.The woman may have been my mother. Anyway I buried them together in the corner of the park.

My next problem was the jewels that I had advised my parents to bury. I was terrified that looters might have got there first, but it was all right. At the appointed place I found the tin and in it the jewels quite intact. My father's gold watch, my mother's pearls and diamond earrings and a few other pieces that had been quite valuable and soon were to be more so.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)