On this day on 21st May

On this day in 1780 prison reformer Elizabeth Gurney was born in Norwich on 21st May, 1780. Elizabeth was the daughter of John Gurney, a successful businessman and a prominent member of the Society of Friends. He was a partner in the famous Gurney Bank and an owner of a woolstapling and spinning factory. Elizabeth's mother, Catherine Gurney, was a member of the Barclay banking family and was also a devout Quaker. She was very involved in charity work and spent part of each day helping the poor of the district. Catherine also insisted that her children spent two hours a day in silent worship.

Soon after having her twelfth child, Catherine Gurney became very ill. When Mrs. Gurney died, Elizabeth was only twelve years old but as one of the eldest girls, was expected to help bring up her younger brothers and sisters. This included Joseph Gurney and Hannah Gurney, the future wife of the anti-slavery campaigner, Thomas Fowell Buxton.

As a young woman Elizabeth was friendly with Amelia Alderson. Amelia's father was a member of the Corresponding Society group that advocated universal suffrage and annual parliaments. At the Alderson home Elizabeth was introduced to the ideas of Mary Wollstonecraft, Tom Paine and William Godwin. For a while she became a republican and rode through Norwich with a tricolor in her hat.

When Elizabeth was eighteen she heard the American Quaker, William Savery, preach in Norwich. Elizabeth begged her father to invite Savery to dinner. Afterwards she wrote: "Today I felt there is a God. I loved the man as if he was almost sent from heaven - we had much serious talk and what he said to me was like a refreshing shower on parched up earth."

After meeting William Savery, Elizabeth decided to devote her energies to helping those in need. Over the next few years she collected old clothes for the poor, visited the sick and and set up a Sunday School in her house where she taught local children to read. Elizabeth Fry was also appointed the committee responsible for running the Society of Friends school at Ackworth. She also visited Joseph Lancaster, a Quaker who ran a school for poor children in London.

In July 1799, Elizabeth was introduced to Joseph Fry, the son of a successful merchant from Essex. Fry was also a Quaker and the two married on 19th August 1800. Elizabeth now had to leave Norwich and went to live in Joseph Fry's family home in Plashet (now East Ham in London). Between 1800 and 1812 Elizabeth Fry gave birth to eight children. Elizabeth remained committed to her religious beliefs and in March, 1811 became a preacher for the Society of Friends. Later that year, Elizabeth attended the inaugural meeting of the British & Foreign Bible Society.

In 1813 a friend of the Fry family, Stephen Grellet, visited Newgate Prison. Grellet was deeply shocked by what he saw but was informed that the conditions in the women's section was even worse. When Grellet asked to see this part of the prison, he was advised against entering the women's yard as they were so unruly they would probably do him some physical harm. Grellet insisted and was appalled by the suffering that he saw.

When Grellet told Elizabeth Fry about the way women were treated in Newgate, she decided that she must visit the prison. Fry discovered 300 women and their children, huddled together in two wards and two cells. Although some of the women had been found guilty of crimes, others will still waiting to be tried. The female prisoners slept on the floor without nightclothes or bedding. The women had to cook, wash and sleep in the same cell. Afterwards she wrote that the "swearing, gaming, fighting, singing and dancing were too bad to be described".

Elizabeth Fry began to visit the women of Newgate Prison on a regular basis. She supplied them with clothes and established a school and a chapel in the prison. Later she introduced a system of supervision that was administered by matrons and monitors. The women now had compulsory sewing duties and Bible reading.

Elizabeth combined prison visiting with her role as wife and mother. Three more children were born over the next few years and she also had to endure the pain of the death of her five year old daughter, Betsy. In 1817 Elizabeth Fry and eleven other Quakers, formed the Association for the Improvement of the Female Prisoners in Newgate. Her brother-in-law, Thomas Fowell Buxton was a member and the following year he published An Inquiry into Prison Discipline, a book based on his investigations of Newgate Prison.

In 1818 Thomas Fowell Buxton was elected as MP for Weymouth and was now in a position to promote Fry's work in the House of Commons. In one speech Buxton pointed out that there were 107,000 people in British prisons, a "a number greater than that of all the other kingdoms of Europe put together."

Elizabeth Fry was invited to give evidence to a House of Commons Committee on London Prisons. She told them how women slept thirty to a room in Newgate Prison, "each with a space of about six feet by two to herself". As she pointed out: "old and young, hardened offenders with those who had committed only a minor offence or their first crime; the lowest of women with respectable married women and maid-servants".

Although the MPs were impressed with Fry's work, they strongly disapproved of some of her comments such as her view that "capital punishment was evil and produced evil results". The vast majority of the members of the House of Commons fully supported the system where criminals could be executed for over 200 offences, such as stealing clothes or passing a forged banknote.

In February 1817 Charlotte Newman and Mary Ann James were sentenced to death for forgery. Fry campaigned to have women prisoners reprived but she was unable to save them from the gallows. The following month she took up the case of Harriet Skelton, one of her favourite prisoners. Skelton, a maidservant to a solicitor, had passed forged banknotes under pressure from her husband. Fry and her brother, Joseph Gurney, visited Lord Sidmouth, the Home Secretary, and pleaded for her life. Sidmouth rejected their arguments and insisted the execution went ahead. In the House of Commons Sidmouth warned that Fry and other reformers were dangerous people as they trying to "remove the dread of punishment in the criminal classes."

Lord Sidmouth rejected Fry's criticism of the British prison system. However, his successor as Home Secretary, Sir Robert Peel, was much more sympathetic, and introduced a series of reforms including the 1823 Gaols Act. As a result of the legislation introduced by Peel, there were regular visits from prison chaplains, gaolers were paid (before they were dependent on fees from the prisoners) and women warders were put in charge of women prisoners.

The problem with Peel's reforms is that they did not apply to debtors' prisons or local town gaols. Fry and Joseph Gurney now went on a tour of British prisons in order to obtain the evidence needed to persuade the government to introduce further legislation. At Aberdeen, the county gaol was housed in an ancient, square tower. In the woman's room, which measured fifteen feet by eight, they found five women and a sick child. At Newcastle-upon-Tyne, prisoners had no space to exercise. In Glasgow, Nottingham, Sheffield, Leeds, York and Liverpool, Fry found conditions as bad, if not worse, than Newgate. After their tour, Fry and Gurney, published a report of what they found in their book, Prisons in Scotland and the North of England.

By the 1820s Elizabeth Fry had become a well-known personality in Britain. It was extremely unusual for a woman to be consulted by men for her professional knowledge. Fry was strongly criticised for playing this role and she was attacked in the press for neglecting her home and family.

In 1824 Fry took a holiday in Brighton where she was shocked by the large number of beggars in the street. She investigated the situation and discovered considerable poverty in the town. Fry decided to form the Brighton District Visiting Society. The plan was to establish a team of voluntary visitors who would go into the homes of the poor where they would provide help and comfort. The scheme was a great success and soon there were District Visiting Societies in towns all over Britain.

In November, 1828, Joseph Fry was declared bankrupt. Although not involved in her husband's business dealings, the bankrupcy affected her good name. In the past subscriptions to the Association for the Improvement of the Female Prisoners in Newgate had been sent to Fry's Bank. Rumours began to circulate that some of this money had been used by Joseph Fry to help solve his financial problems. Although totally untrue, for a time these stories damaged the reputation of both Elizabeth Fry and the charities she was involved in. Elizabeth's brother, Joseph Gurney, took over Fry's business interests and made arrangements for all debtors to be paid.

Joseph Gurney also arranged for Elizabeth to receive £1600 a year and this enabled her to continue her charity work. Although prison reform was her main concern she also campaigned for the homeless in London and improvements in the way patients were treated in mental asylums. Fry also promoted the reform of workhouses and hospitals.

Fry also became concerned about the quality of nursing staff. In 1840 she started a training school for nurses in Guy's Hospital. Fry nurses wore their own uniform and were expected to tend to their patients spiritual, as well as their physical needs. Florence Nightingale wrote to Fry to explain how she had been influenced by her views on the training of nurses. Later, when Nightingale went to the Crimean War, she took a group of Fry nurses with her to look after the sick and wounded soldiers.

Queen Victoria took a close interest in her work and the two women met several times. Victoria gave her money to help with her charitable work. In her journal, Victoria wrote that she considered Fry a "very superior person". It is claimed that Victoria, who was forty years younger than Elizabeth Fry, might have modelled herself on this woman who successfully combined the roles of mother and public figure.

After a short illness, Elizabeth Fry died on 12th October, 1845. Although Quakers do not have a funeral service, over a thousand people stood in silence as she was buried at the Society of Friend's graveyard at Barking.

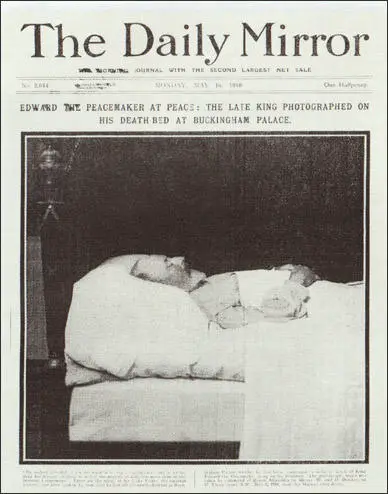

On this day in 1910 the Daily Mirror published a photo of the dead Edward VII lying on his bed in Buckingham Palace. "Public reaction was predictable: shock, horror, outrage and a stampede to buy copies at the newsagents. The coup revealed the public's morbid fascination for celebrated corpses."

Complaints that the Daily Mirror had displayed atrocious taste by intruding on private grief were undermined when Hannen Swaffer, the newspaper's Art Editor, provided information on how the photograph was obtained. Swaffer heard about the picture while drinking beer in a public house. He claimed that he had offered £100 to ask Queen Alexander if the paper could publish it. According to Swaffer's account, the Queen replied, "It can only go in one paper, the Mirror, because that is my favourite."

On this day in 1916 George Riddell writes in his diary about the planned overthrow of H. H. Asquith, as prime minister. During the First World War Riddell, the managing director of the News of the World, was very close to David Lloyd George. He claimed in his diary that Lloyd George worked very closely with Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, the owner of The Times and The Daily Mail, to overthrow Asquith. "There is no doubt that Lloyd George and Northcliffe are acting in concert... Lloyd George is growing to believe more and more every day that he (Lloyd George) is the only man to win the War. His attitude to the PM is changing rapidly. He is becoming more and more critical and antagonistic. It looks as if Lloyd George and Northcliffe are working to dethrone Mr A."

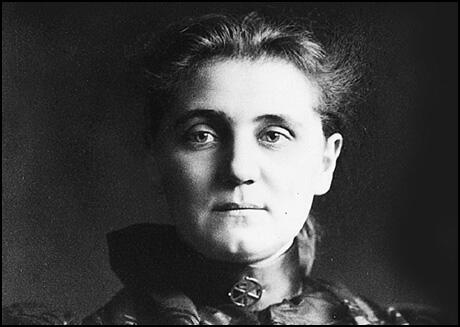

On this day in 1935 political activist Jane Addams died. Jane, the eighth child of a successful businessman, was born in Cedarville, Illinois on 6th September, 1860. Jane's mother died when she was only three years old but she was deeply influenced by her father who was a Quaker but had supported Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War.

According to Harriet Hyman Alonso: "Jane Addams was greatly influenced by her father, who stood out in the community as a great supporter of Abraham. Lincoln and an opponent of slavery and was a God-fearing man who, his daughter claimed, favored Quakerism although regularly attending services in both Methodist and Presbyterian churches. Addams, therefore, was reared in a religious home that valued humanitarianism. As a girl, she expressed sympathy for former slaves and other impoverished people in the community. As many other children whose parents opposed slavery but supported the Civil War, Addams grew up aware of the dilemma between fighting a just war and maintaining moral witness against all violence. These values made her a perfect candidate for a lifetime of work around social justice issues."

Edmund Wilson claimed that: "A little girl with curvature of the spine, whose mother had died when she was a baby, she abjectly admired her father, a man of consequence in frontier Illinois, a friend of Lincoln and a member of the state legislature, who had a floor mill and a lumber mill on his place. Whenever there were strangers at Sunday school, she would try to walk out with her uncle so that her father should not be disgraced by people's knowing that such a fine man had a daughter with a crooked spine."

Jane Addams graduated from Rockford Female Seminary in 1881. She then attended the Women's Medical College in Philadelphia, but was forced to abandon her studies after undergoing a serious spinal operation. Eleanor J. Stebner, the author of The Women of Hull House (1997), has argued: "For the next seven years, Addams struggled to find her voice and a way to take an active part in the world she encountered."

In 1888, while on a European tour, Jane Addams and Ellen Starr, visited the university settlement, Toynbee Hall in the East End of London. Named after the social reformer, Arnold Toynbee, the settlement was run by Samuel Augustus Barnett, canon of St. Jude's Church. Situated in Commercial Street, Whitechapel, Toynbee Hall was Britain's first university settlement. The idea was to create a place where students from Oxford University and Cambridge University could work among, and improve the lives of the poor during their summer holidays. The settlement also served as a base for Charles Booth and his group of researchers working on the Life and Labour of the People in London.

When Jane Addams and Ellen Starr returned to Chicago in 1889, they decided to start a similar project in Chicago. Helen Culver agreed to rent them Hull House for $60 a month. This large, abandoned mansion had been built by the wealthy businessman, Charles J. Hull, in 1856. Situated in Halstead Street, most of the people living in the area were recently arrived immigrants from Italy and Germany.

Jane Addams and Ellen Starr moved in to Hull House on 18th September, 1889. They began by inviting people living in the area to hear reading of George Eliot's Romola and to look at slides of Florentine art. After talking to the people who visited the house, it soon became clear that the women had a desperate need for a place where they could bring their young children. Addams and Starr decided to start a kindergarten and provide a room where the mothers could sit and talk. Jenny Dow, who lived in an expensive part of Chicago, agreed to come to Hull House to run the nursery school. Within three weeks the kindergarten had enrolled twenty-four children with 70 more on the waiting list.

Other activities soon followed. Jane Addams ran a club for teenage boys. Whereas Ellen Starr provided lessons in cooking and sewing for young girls. Local university teachers and students were also recruited to provide free lectures on a wide variety of different topics.

Inspired by the ideas of William Morris and John Ruskin, the women decided to turn Hull House into an art gallery. While in Europe the two women had collected reproductions of paintings and these were now hung in the various rooms of the house. Ellen Starr organized art classes and exhibitions as well as developing a scheme where people could borrow art reproductions to hang in their own homes.

Italian and German evenings were also organized at Hull House. Local people presented songs, dances, games and food associated with the countries from where they used to live. This was probably the most successful of their early ventures as it provided an opportunity for local people to make their own contribution to the venture. As Addams later recalled, it soon became clear that the object of the settlement program should be to "help the foreign-born conserve and keep whatever of value their past life contained and to bring them into contact with a better class of Americans."

In 1890 Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr were joined at Hull House by Julia Lathrop. All three women had been students at Rockford Seminary together in the 1980s. Lathrop, who had been trained as a lawyer by her father, the United States senator, William Lathrop, was an excellent organizer, and took over the day to day running of the settlement.

Jane Addams, Ellen Gates Starr and Julia Lathrop gradually became more involved in the community where they were living. They were shocked by the poor housing, the overcrowding and the poverty that the people were having to endure. Addams wrote to her step-brother that she was "overpowered by the misery and narrow lives" of these people.

In the early days of Hull House, the three women were influenced by the Christian Socialism that had inspired the creation of Toynbee Hall. This was reinforced by the arrival in 1891 of Florence Kelley at Hull House. A member of the Socialist Labor Party, Kelley had considerable experience of political and trade union activity. It was Kelley who was mainly responsible for turning Hull House into a centre of social reform.

The presence of Florence Kelley in Hull House attracted other social reformers to the settlement. This included Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Alice Hamilton, Mary McDowell, Charles Beard, Mary Kenney, Charlotte Perkins, Alzina Stevens and Sophonisba Breckinridge. Working-class women, such as Kenney and Stevens, who had developed an interest in social reform as a result of their trade union work, played an important role in the education of the middle-class residents at Hull House. They in turn influenced the working-class women. As Kenney was later to say, they "gave my life new meaning and hope".

Addams met Mary White Ovington, the founder of the Greenpoint Settlement in Brooklyn. Ovington remembers Addams telling her: "If you want to be surrounded by second-rate ability, you will dominate your settlement. If you want the best ability, you must allow great liberty of action among your residents."

Florence Kelley and several other women based at Hull House carried out research into the sweating trade in Chicago and this led to the passing of the pioneering Illinois Factory Act (1893). Kelley was recruited by the state's new governor, John Peter Altgeld, as the chief factory inspector, and two other women involved in the research, Alzina Stevens and Mary Kenney, became inspectors in Illinois.

Helen Culver, who owned Hull House, also gave the women other adjacent property. Wealthy people in Chicago contributed money, including Louise Bowen who provided three quarters of a million dollars. This enabled the group to expand its activities. An art gallery was added in 1891, a coffee house and gymnasium in 1893, a club house in 1898 and a theatre in 1899.

In 1903 several women associated with Hull House, including Jane Addams, Mary Kenney, Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley and Sophonisba Breckinridge, were involved in establishing the Women's Trade Union League. Union meetings were often held at Hull House and members of the settlement helped support workers during industrial disputes. This resulted in some wealthy people withdrawing their support for Hull House. One businessman wrote that Hill House had "been so thoroughly unionized that it has lost its usefulness and has become a detriment and harm to the community as a whole."

The Hull House complex was not completed until 1907. The settlement now had thirteen buildings spread over a large city block. There were around 70 people living in Hull House and it cost the settlement over $26,500 to run the house and its programs. Rents and sales raised $12,000 but the rest had to come from donations.

On 3rd September 1908, William English Walling published his article, Race War in the North. Walling complained that "a large part of the white population" in the area were waging "permanent warfare with the Negro race". He quoted a local newspaper as saying: "It was not the fact of the whites' hatred toward the negroes, but of the negroes' own misconduct, general inferiority or unfitness for free institutions that were at fault." Walling argued that they only way to reduce this conflict was "to treat the Negro on a plane of absolute political and social equality".

Walling argued that the people behind the riots were seeking economic benefits: "If the white laborers get the Negro laborers' jobs; if masters of Negro servants are able to keep them under the discipline of terror as I saw them doing in Springfield; if white shopkeepers and saloon keepers get their colored rivals' trade; if the farmers of neighboring towns establish permanently their right to drive poor people out of their community, instead of offering them reasonable alms; if white miners can force their negro fellow-workers out and get their positions by closing the mines, then every community indulging in an outburst of race hatred will be assured of a great and certain financial reward, and all the lies, ignorance and brutality on which race hatred is based will spread over the land."

Walling suggested that racists were in danger of destroying democracy in the United States: "The day these methods become general in the North every hope of political democracy will be dead, other weaker races and classes will be persecuted in the North as in the South, public education will undergo an eclipse, and American civilization will await either a rapid degeneration or another profounder and more revolutionary civil war, which shall obliterate not only the remains of slavery but all other obstacles to a free democratic evolution that have grown up in its wake. Yet who realizes the seriousness of the situation, and what large and powerful body of citizens is ready to come to their aid.

Mary Ovington, a journalist working for the New York Evening Post, responded to the article by writing to Walling and inviting him and a few friends to her apartment on West Thirty-Eighth Street. Ovington was impressed with Walling: "It always seemed to me that William English Walling looked like a Kentuckian, tall, slender; and though he might be talking the most radical socialism, he talked it with the air of an aristocrat."

They decided to form the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). The first meeting of the NAACP was held on 12th February, 1909. Early members included Jane Addams, William English Walling, Anna Strunsky, Mary Ovington, Josephine Ruffin, Mary Talbert, Lillian Wald, Florence Kelley, Mary Church Terrell, Inez Milholland, George Henry White, William Du Bois, Charles Edward Russell, John Dewey, Charles Darrow, Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, William Dean Howells, Fanny Garrison Villard, Oswald Garrison Villard and Ida Wells-Barnett.

A strong supporter of women's suffrage, Addams was vice-president of the National American Women's Suffrage Association (1911-14). Addams controversially supported Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Party in the 1912 presidential elections. Some of the her friends were highly critical of his aggressive foreign policy and his unwillingness to openly support African American civil rights.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Jane Addams and a group of women pacifists in the United States, began talking about the need to form an organization to help bring it to an end. On the 10th January, 1915, over 3,000 women attended a meeting in the ballroom of the New Willard Hotel in Washington and formed the Woman's Peace Party. Addams was elected chairman and other women involved in the organization included Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley, Alice Hamilton, Anna Howard Shaw, Belle La Follette, Fanny Garrison Villard, Emily Balch, Jeanette Rankin, Lillian Wald, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Mary Heaton Vorse, Freda Kirchwey, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Crystal Eastman, Carrie Chapman Catt and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

In April 1915, Arletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited members of the Woman's Peace Party to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Addams was asked to chair the meeting and Alice Hamilton, Mary Heaton Vorse, Julia Lathrop, Leonora O'Reilly, Sophonisba Breckinridge, Grace Abbott and Emily Bach went as delegates from the United States. Others who went to the Hague included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, (England); Chrystal Macmillan (Scotland) and Rosika Schwimmer (Hungary). Afterwards, Addams, Jacobs, Macmillan, Schwimmer and Balch went to to London, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Rome and Paris to speak with members of the various governments in Europe. During this time they met Edward Grey (13th May), Herbert Asquith (14th May), Gottlieb von Jagow (21st May), Theobold von Bethmann-Hollweg (22nd May), Karl von Sturgkh (26th May), Théophile Delcassé (12th June) and Rene Viviani (14th June).

The women were attacked in the press by Theodore Roosevelt who described them as "hysterical pacifists" and called their proposals "both silly and base". Addams was selected for particular criticism. One man wrote in the Rochester Herald, "In the true sense of the word, she is apparently without education. She knows no more of the discipline and methods of modern warfare than she does of its meaning. If the woman conceded by her sisters to be the ablest of her sex, is so readily duped, so little informed, men wonder what degree of intelligence is to be secured by adding the female vote to the electorate."

Henry Ford, the wealthy American businessman, soon made it clear he opposed the war and supported the decision of the Woman's Peace Party to organize a peace conference in Holland. After the conference Addams, Oswald Garrison Villard, and Paul Kellogg, met with Ford and suggested he should sponsor an international conference in Stockholm to discuss ways that the conflict could be brought to an end. During this period Theodore Roosevelt described Addams as "the most dangerous woman in America."

Henry Ford came up with the idea of sending a boat of pacifists to Europe to see if they could negotiate an agreement that would end the war. He chartered the ship Oskar II, and it sailed from Hoboken, New Jersey on 4th December, 1915. Addams planned to be on the ship but three days before it was due to leave she became seriously ill with tuberculosis of the kidneys. The Ford Peace Ship reached Stockholm in January, 1916, and a conference was organized with representatives from Denmark, Holland, Norway, Sweden and the United States. However, unable to persuade representatives from the warring nations to take part, the conference was unable to negotiate an Armistice.

In 1918 Herbert Hoover recruited Addams to his Department of Food Administration. She toured the country making speeches encouraging the people of America to help conserve and increase production of food. This upset some pacifists who felt that any support of the war effort was morally wrong. However, she was praised by some of her former critics. The editor of the Los Angeles Times wrote: "now she is seeing clearly again, and her service is with the country, with the administration, with the Allies, wholehearted and whole-souled."

Jane Addams was again criticised in April 1919 when she lead the American delegation to the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) conference in Zurich. Among the delegates were Florence Kelley, Alice Hamilton, Emily Balch, Jeanette Rankin and Lillian Wald. At the conference Addams was elected president of the WILPF and Balch became secretary-treasurer.

In 1919 Woodrow Wilson appointed A. Mitchell Palmer as his attorney general. Palmer had previously been associated with the progressive wing of the party and had supported women's suffrage and trade union rights. However, once in power, Palmer's views on civil rights changed dramatically. Worried by the revolution that had taken place in Russia, Palmer became convinced that Communist agents were planning to overthrow the American government. Palmer recruited John Edgar Hoover as his special assistant and together they used the Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918) to launch a campaign against radicals and left-wing organizations.

On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists were arrested in what became known as the Palmer Raids. Palmer and Hoover found no evidence of a proposed revolution but large number of these suspects were held without trial for a long time. The vast majority were eventually released but Emma Goldman and 247 other people, were deported to Russia.

In January, 1920, another 6,000 were arrested and held without trial. Palmer and Hoover found no evidence of a proposed revolution but a large number of these suspects, many of them members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), continued to be held without trial. When Palmer announced that the communist revolution was likely to take place on 1st May, mass panic took place. In New York, five elected Socialists were expelled from the legislature.

Jane Addams was appalled by the way people were being persecuted for their political beliefs and in 1920 joined with Roger Baldwin, Norman Thomas, Chrystal Eastman, Paul Kellogg, Clarence Darrow, John Dewey, Abraham Muste, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Upton Sinclair to form the American Civil Liberties Union.

During her life Jane Addams wrote articles about social problems in a variety of magazines including American Magazine, McClures, Crisis, and Ladies Home Journal. Addams also wrote several books including, Democracy and Social Ethics (1902), Newer Ideals of Peace (1907), Spirit of Youth (1909), Twenty Years at Hull House (1910), A New Conscience and an Ancient Evil (1912), Peace and Bread in Time of War (1922) and The Second Twenty Years at Hull House (1930).

In 1927 Jane Addams joined with John Dos Passos, Alice Hamilton, Jane Addams, Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Ben Shahn, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Floyd Dell, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells in an effort to prevent the execution of Nicola Sacco and Bertolomeo Vanzetti. Although Webster Thayer, the original judge, was officially criticised for his conduct at the trial, the execution went ahead on 23rd August 1927.

Even when Jane Addams was in her seventies right-wing figures continued to attack her as the "most dangerous woman" in the United States. In 1934 Elizabeth Dilling wrote in her book, The Red Network, that: "Jane Addams has been able to do more probably than any other living woman to popularize pacifism and to introduce radicalism into colleges, settlements, and respectable circles. The influence of her radical proteges, who consider Hull House their home center, reaches out all over the world."

Jane Addams, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931, remained president of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom until her death on 21st May, 1935.

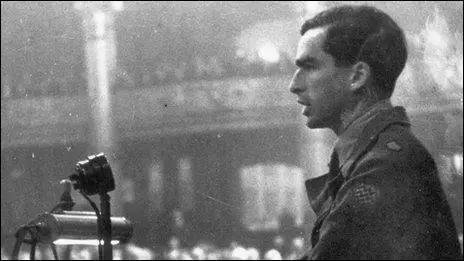

On this day in 1945 Denis Healey makes speech at the 1945 Labour Party Conference: "The upper classes in every country are selfish, depraved, dissolute and decadent. The struggle for socialism in Europe ... has been hard, cruel, merciless and bloody. The penalty for participation in the liberation movement has been death for oneself, if caught, and, if not caught oneself, the burning of one's home and the death by torture of one's family ... Remember that one of the prices paid for our survival during the last five years has been the death by bombardment of countless thousands of innocent European men and women."

On this day in 1952 blacklisted actor John Garfield dies. In June, 1950, three former FBI agents and a right-wing television producer, Vincent Hartnett, published Red Channels, a pamphlet listing the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organisations before the Second World War but had not so far been blacklisted. The names had been compiled from FBI files and a detailed analysis of the Daily Worker, a newspaper published by the American Communist Party. A free copy was sent to those involved in employing people in the entertainment industry. All those people named in the pamphlet were blacklisted until they appeared in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and convinced its members they had completely renounced their radical past.

John Garfield appeared before the HUAC on 23rd April, 1951. He answer questions and denied he ever joined the American Communist Party or knew any of its members. He did admit to being a supporter of left-wing causes and during the 1930s had spoken at Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee meetings and in the 1948 Presidential Election he had advocated the election of Henry Wallace, the Progressive Party candidate.

Donald L. Jackson questioned Garfield's account about his knowledge of what was going on in Hollywood: "Do you contend that during the seven years or more that you were in Hollywood and in close contact with a situation in which a number of Communist cells were operating on a week-to-week basis, with electricians, actors, and every class represented, that during the entire period of time you were in Hollywood you did not know of your own personal knowledge a member of the Communist Party?"

Garfield replied: "When I was originally requested to appear before the committee, I said that I would answer all questions, fully and without any reservations, and that is what I have done. I have nothing to be ashamed of and nothing to hide. My life is an open book. I was glad to appear before you and talk with you. I am no Red. I am no pink. I am no fellow traveler. I am a Democrat by politics, a liberal by inclination, and a loyal citizen of this country by every act of my life."

Roy M. Brewer of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees appeared on 17th May. He testified that he did not believe that John Garfield was telling the truth. He argued that it was impossible for an actor in Hollywood and not to be aware of the power of the American Communist Party. "I do not think the opinion of one man is of much value, but I think if you could document the employment records of those individuals that were not acceptable to the Communist group as against those individuals who were in the forefront of it, I think you would find a rather substantial indication that there were influences at work. Those influences work in many, many ways. Lots of times the opinion of a secretary or of a clerk in a casting bureau can make the difference between whether one man is hired or another man is hired. I can see, from my standpoint, knowing the set-up in Hollywood, how easy it would be for an underground movement to use influence in such a way that an individual without such protection would be at a disadvantage, and I am of the definite opinion that was the case. I think it can be proven by records. I haven't attempted to do that, but in my judgment it could be done."

Some members of the Group Theatre like Elia Kazan, Clifford Odets and Lee J. Cobb testified and named other members of left-wing groups. Other former members, including Garfield, Stella Adler, Will Geer, Howard Da Silva, John Randolph, and Joseph Bromberg refused to give the names of left-wing friends and were blacklisted.

John Garfield died of a heart attack on 21st May, 1952. Only thirty-nine years old, his family and friends claimed that the stress brought on by McCarthyism was a major factor in his early death. His daughter later recalled: "It killed him, it really killed him. He was under unbelievable stress. Phones were being tapped. He was being followed by the FBI. He hadn't worked in 18 months. He was finally supposed to do Golden Boy on CBS with Kim Stanley. They did one scene. And then CBS canceled it. He died a day or two later."

On this day in 2007 the Guardian publishes an article about anti-Nazi activist, Marion Yorck von Wartenburg. Marion Yorck von Wartenburg was born Marion Winter in Berlin on 14th June 1904. She was the third of six children of a senior civil servant responsible for the German state's role in supporting the performing arts. Marion was educated at the Grunewald-Gymnasium in Berlin. A fellow student was Dietrich Bonhoeffer. She went on to university there to study medicine, but switched to law, in which she gained a doctorate at the age of 25. "Unusually for a woman at the time, she started training as a judge, a career separate from advocacy in Germany."

In 1930 she married Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg, a year older, whom she had met while they were both studying law. Although her background was upper middle class, Marion's marriage to a landed aristocrat from a family with several estates led her to give up the law and help with the management of the estate.

In 1936 Wartenburg was appointed as assistant secretary to the Reich Price Commission in Berlin. He refused to join the Nazi Party and therefore never received any further promotions. Some of his associates, including Hans Gisevius, a former assistant secretary in the Ministry of the Interior, was also strongly opposed to Adolf Hitler.

Wartenburg opposition to fascism increased after Kristallnacht (9-10 November 1938). In 1940 along with Helmuth von Moltke he established the Kreisau Circle, a small group of intellectuals who opposed Hitler. Other people who joined included Adam von Trott, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Wilhelm Leuschner, Julius Leber, Adolf Reichwein, Carlo Mierendorff, Alfred Delp, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Ulrich-Wilhelm Graf von Schwerin, Dietrich Bonhoffer, Harald Poelchau and Jakob Kaiser. Marion and Freya von Moltke, were the only women who attended these meetings. It has been pointed out that they "could have faced the death penalty simply for serving food and drinks to the conspirators."

The group represented a broad spectrum of social, political, and economic views, they were best described as Christian and Socialist. A. J. Ryder has pointed out that the Kreisau Circle "brought together a fascinating collection of gifted men from the most diverse backgrounds: noblemen, officers, lawyers, socialists, trade unionists, churchmen." Joachim Fest argues that the "strong religious leanings" of this group, together with its ability to attract "devoted but undogmatic socialists," but has been described as its "most striking characteristic."

On 8th January, 1943, a group of conspirators, including, Helmuth von Moltke, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Johannes Popitz, Ulrich Hassell, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Adam von Trott, Ludwig Beck and Carl Goerdeler met at Wartenburg's home. Hassell was uneasy with the utopianism of the of the Kreisau Circle, but believed that the "different resistance groups should not waste their strength nursing differences when they were in such extreme danger". Wartenburg, Moltke and Hassell were all concerned by the suggestion that Goerdeler should become Chancellor if Hitler was overthrown as they feared that he could become a Alexander Kerensky type leader.

Claus von Stauffenberg decided to carry out the assassination himself. But before he took action he wanted to make sure he agreed with the type of government that would come into being. Conservatives such as Carl Goerdeler and Johannes Popitz wanted Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben to become the new Chancellor. However, socialists in the group, such as Julius Leber and Wilhelm Leuschner, argued this would therefore become a military dictatorship. At a meeting on 15th May 1944, they had a strong disagreement over the future of a post-Hitler Germany.

Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg was arrested along with Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg and Friedrich Olbricht. His trial took place on 7th August, 1944. It resulted in the conviction of Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben, Colonel-General Erich Hoepner, General-Major Helmuth Stieff, General Paul von Hase (the commandant of the Berlin garrison) and several junior officers. All the men were tried by Roland Freisler, the notorious Nazi judge.

Joseph Goebbels ordered that every minute of the trial should be filmed so that the movie could be shown to the troops and the civilian public as an example of what happened to traitors. Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg wrote in his last letter to his wife: "I believe I have gone some way to atone for the guilt which is our heritage." Wartenburg was particularly fearless and steadfast. He told the court: "The vital point running through all these questions is the totalitarian claim of the state over the citizen to the exclusion of his religious and moral obligation toward God."

It is estimated that 4,980 people were arrested by the Gestapo. Heinrich Himmler gave instructions that these men should be tortured. He also ordered that family members should also be punished: "When they (the people's Germanic forbears) put a family under the ban and declared it outlawed or when there was a vendetta in the family, they were totally consistent about it. If the family was outlawed or banned; it will be exterminated. And in a vendetta they exterminated the entire clan down to its last member. The Stauffenberg family will be exterminated down to its last member."

Marion was arrested and put in solitary confinement for three months. What became known as the "kith and kin" law, was a particularly sophisticated form of torture. When interrogating suspects the Gestapo could, quite legally, threaten to ill-treat their wives, children, parents, brothers and sisters or other relatives.

Released without charge, she managed to get to the Yorck estates, which were soon overrun by the advancing Red Army. Although she eluded the attentions of Soviet soldiers, she was jailed again in Poland for another three months and beaten up by communist guards who refused to accept that she was not a supporter of fascism.

After the war, Marion Yorck went back to being a judge, helped by her record as an anti-Nazi, and acquired a reputation as fair but firm in the criminal trials she supervised. The Yorcks had no children and Marion did not remarry, keeping the Yorck family name in honour of her husband. But for half a century she lived with Ulrich Biel, a German politician.

Marion Yorck von Wartenburg died aged 102 on 13th April, 2007.