On this day on 8th July

On this day in 1793 Thomas Hardy made a speech on parliamentary reform. "We conceive it necessary to direct the public eye, to the cause of our misfortunes, and to awaken the sleeping reason for our countrymen, to the pursuit of the only remedy which can ever prove effectual, namely; a thorough reform of Parliament, by the adoption of an equal representation obtained by annual elections and universal suffrage. To obtain a complete representation is our only aim - condemning all party distinctions, we seek no advantage with every individual of the community will not enjoy equally with ourselves."

On this day in 1822 poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, the son of Sir Timothy Shelley, the M.P. for New Shoreham, was born at Field Place near Horsham, in 1792. Sir Timothy Shelley sat for a seat under the control of the Duke of Norfolk and supported his patron's policies of electoral reform and Catholic Emancipation.

Shelley was educated at Eton and Oxford University and it was assumed that when he was twenty-one he would inherit his father's seat in Parliament. As a young man he was taken to the House of Commons where he met Sir Francis Burdett, the Radical M.P. for Westminster. Shelley, who had developed a strong hatred of tyranny while at Eton, was impressed by Burdett, and in 1810 dedicated one of his first poems to him. At university Shelley began reading books by radical political writers such as Tom Paine and William Godwin.

At university Shelley wrote articles defending Daniel Isaac Eaton, a bookseller charged with selling books by Tom Paine and the much persecuted Radical publisher, Richard Carlile. He also wrote The Necessity of Atheism, a pamphlet that attacked the idea of compulsory Christianity. Oxford University was shocked when they discovered what Shelley had written and on 25th March, 1811 he was expelled.

Shelley eloped to Scotland with Harriet Westbrook, a sixteen year old daughter of a coffee-house keeper. This created a terrible scandal and Shelley's father never forgave him for what he had done. Shelley moved to Ireland where he made revolutionary speeches on religion and politics. He also wrote a political pamphlet A Declaration of Rights, on the subject of the French Revolution, but it was considered to be too radical for distribution in Britain.

Percy Bysshe Shelley returned to England where he became involved in radical politics. He met William Godwin the husband of Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of Vindication of the Rights of Women. Shelley also renewed his friendship with Leigh Hunt, the young editor of The Examiner. Shelley helped to support Leigh Hunt financially when he was imprisoned for an article he published on the Prince Regent.

Leigh Hunt published Queen Mab, a long poem by Shelley celebrating the merits of republicanism, atheism, vegetarianism and free love. Shelley also wrote articles for The Examiner on polical subjects including an attack on the way the government had used the agent provocateur William Oliver to obtain convictions against Jeremiah Brandreth.

In 1814 Shelley fell in love and eloped with Mary, the sixteen-year-old daughter of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. For the next few years the couple travelled in Europe. Shelley continued to be involved in politics and in 1817 wrote the pamphlet A Proposal for Putting Reform to the Vote Throughout the United Kingdom. In the pamphlet Shelley suggested a national referendum on electoral reform and improvements in working class education.

Percy Bysshe Shelley was in Italy when he heard the news of the Peterloo Massacre. He immediately responded by writing The Mask of Anarchy, a poem that blamed Lord Castlereagh, Lord Sidmouth and Lord Eldon for the deaths at St. Peter's Fields. In The Call to Freedom Shelley ended his argument for non-violent mass political protest with the words: "Which in sleep had fallen on you - Ye are many - they are few."

In 1822 Shelley, moved to Italy with Leigh Hunt and Lord Byron where they published the journal The Liberal. By publishing it in Italy the three men remained free from prosecution by the British authorities. The first edition of The Liberal sold 4,000 copies. Soon after its publication, Percy Bysshe Shelley was lost at sea on 8th July, 1822 while sailing to meet Leigh Hunt.

On this day in 1867 Käthe Schmidt, the daughter of Katharina and Karl Schmidt, was born in the industrial city of Königsberg, on 8th July 1867. Her father was a stone mason and house builder, who developed strong socialist opinions after reading the work of Karl Marx. Her mother was the daughter of Julius Rupp, a nonconformist religious leader who suffered much political abuse.

She was a "quiet, shy and nervous" child and spent most of her time with her older siblings, Julie and Konrad: "There were endless places to play and numerous adventures to be had in those yards. For example, a pile of coal had been unloaded from a boat and dumped in the yard in such a way that it sloped up gently and then fell off sharply on the side facing our garden. It was a risky matter to climb up almost to the brink. I myself never dared, but Konrad did. Another boy who tried it was hurt."

Karl Schmidt was educated to become a lawyer but had not followed his profession because his political, social, and moral views made it impossible for him to serve what he considered to be the authoritarian government led by Otto von Bismarck. He joined the Social Democratic Party (SDP). According to Martha Kearns: "Schmidt was a man of the future in his educational as well as political views. Unlike many Prussian fathers... the head of the Schmidt family was not a strict disciplinarian and he did not believe in corporal punishment. A moral idealist, he taught his children to correct their behaviour through self-control, choosing to guide rather than force their development.... In a day when girls were rarely encouraged to aspire to roles other than those of wife and mother, he personally helped to develop the individual talents of each of his three daughters."

Käthe was also influenced by her grandfather who also held strong socialist beliefs and had been imprisoned because his religious views differed from those of Fredrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia. She later recalled: "He was always ready to give, was always kindly and informative, and often laconically humorous... He was tall, thin, dressed in black up to his chin, his eye-glasses having a faintly bluish tinge, his blind eye covered by a somewhat more opaque glass."

Käthe greatly admired her grandfather: "I respected him, but was timid in his presence because I was a bashful child. I did not have the personal relationship with him which my two older sisters and, above all, my brother experienced. Along with the other children of the congregation I had religious instruction under him, an instruction which perhaps passed over the heads of most of the children, myself included. The teaching consisted of religious history, discussion of the gospels, and commentary on the Sunday sermon. A loving God was never brought home to us."

It was very important to Karl Schmidt that his children grew up with a sympathy for the plight of the working-class. Käthe remembers her father reading the poem, The Song of the Shirt, written by the English poet, Thomas Hood. Käthe later explained that as her father "read the last lines, he became so moved that his voice grew fainter and fainter until he was unable to finish. His silent identification with the poor seamstress filled the room. In the silence Käthe, too, experienced the sweat, heat, and grind of a shirt factory and the working woman's numb fatigue."

All three girls were gifted artists. The youngest daughter, Lise, was especially talented. One day Käthe overheard her father tell her mother that Lise's drawings were so good that she would "soon be catching up to Käthe". She wrote in her diary: "When I heard this I felt envy and jealously for probably the first time in my life. I loved Lise dearly. we were very close to one another and I was happy to see her progress up to the point where I began; but everything in me protested against her going beyond that point. I always had to be ahead of her."

Her father became convinced that Käthe could become a great artist. In 1881 he arranged for her to have lessons with Rudolf Mauer, a local copper engraver. Käthe made drawings from plaster casts and copied drawings by famous artists. Käthe later recalled that her father and grandfather, Julius Rupp, were both important to her development: "Although I thought that Grandfather's religious force did not live on in me, a deep respect remained, a respect for his teachings, his personality and all the Congregation stood for. I might say that in recent years I have felt both Grandfather and Father within myself, as my origins. Father was nearest to me because he had been my guide to socialism, in the sense of the longed-for brotherhood of men." He once told her: "Man is not here to be happy, but to do his duty".Her grandfather died in 1884.

The Schmidt family involvement with the Social Democratic Party (SDP) enabled Käthe to meet another young member, Karl Kollwitz. He was an orphan who lived with a family in Konigsberg. Like her father he was passionately interested in politics and introduced her to the writings of August Bebel. This included his pioneering work, Woman and Socialism (1879). In the book Bebel argued that it was the goal of socialists "not only to achieve equality of men and women under the present social order, which constitutes the sole aim of the bourgeois women's movement, but to go far beyond this and to remove all barriers that make one human being dependent upon another, which includes the dependence of one sex upon another."

Käthe was particularly impressed with one passage of the book that stated: "In the new society women will be entirely independent, both socially and economically... The development of our social life demands the release of woman from her narrow sphere of domestic life, and her full participation in public life and the missions of civilisation." Bebel also predicted the dissolution of marriage, believing that socialism would free women from their second-class status.

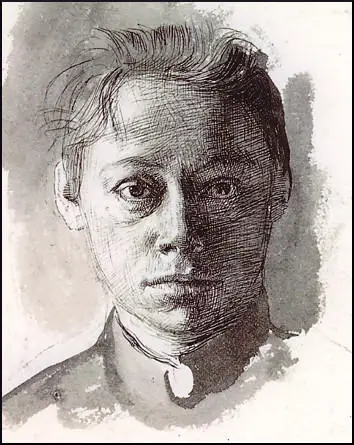

At the age of sixteen Käthe tried to enter the Königsberg Academy of Art. However, as a female, her application was rejected and so her father arranged for her to study under the painter, Emil Neide. He introduced her to work of the French artist, Gustave Courbet, who was the leader of the realist movement. Influenced by this attempt to capture the reality of everyday life, she completed The Emigrants, a work that had been inspired by a poem of that name by Ferdinand Freiligrath.

In 1884 Karl Schmidt arranged for Käthe and Lise to visit Berlin. While in the city they stayed with their elder sister, Julie, and her husband. He was a close friend of the young poet and dramatist, Gerhart Hauptmann. He invited Käthe and Lise to a dinner party that was attended by two artists, Hugo Ernst Schmidt and Arno Holz. Hauptman described Käthe as "fresh as a rose in dew, a charming, clever girl, who, because of her extreme modesty, did not speak freely about her calling as an artist but let it be known by her sure, sensitive manner." Käthe was also impressed with Hauptman: "It was an evening that left its mark... a wonderful foretaste of the life which was gradually but irresistibly opening up for me."

Karl Kollwitz became a medical student and in 1884 he asked Käthe to marry him. Her agreement to his proposal upset her father who feared that marriage would inhibit her artistic career. He arranged for her to study at the Berlin School for Women Artists, where she studied under Karl Stauffer-Bern. He introduced her to the work of Max Klinger. Käthe's biographer, Martha Kearns, has pointed out: "She (Käthe) had never heard of Max Klinger, Prussia's most skilled artist of the then-popular naturalism, a school of thought which deemed people to be predetermined victims in a bitter struggle for survival. As an art form, naturalism emphasized photo like images of actual persons, scenes, and conditions, often in the most minute, even microscopic detail. Unlike artists working in other styles, naturalist artists featured women as subjects as frequently as men."

At Stauffer-Bern's suggestion, Käthe went to see Klinger's Ein Leben, at a Berlin exhibition. It was a series of fifteen etchings about a woman who had lost her virginity to her lover and who thus, in the eyes of the bourgeoisie, had "fallen" into unredeemable sin. The series reflected the double standard held against women at the turn of the twentieth century. This extremely accomplished and powerful series inspired Käthe and she wrote in her journal: "It was the first work of his I had seen, and it excited me tremendously."

Käthe became friends with fellow art student, Emma Jeep. As women they were not allowed to attend life-drawing classes (this did not change in Berlin until 1893). At Käthe's request, Jeep often posed nude for her in the privacy of their rooms. The two women became close friends and this relationship lasted for the rest of Käthe life. At the time, Jeep was highly critical of Käthe's decision to get engaged. Jeep was a feminist and believed marriage would damage a woman's career as an artist.

In her journal Käthe admitted that she was attracted to women: "Although my leaning toward the male sex was dominant, I also felt frequently drawn toward my own sex-an inclination which I could not correctly interpret until much later on. As a matter of fact I believe that bisexuality is almost a necessary factor in artistic production; at any rate, the tinge of masculinity within me helped me in my work." Her biographer, Martha Kearns, has pointed out: "It is not known whether she ever acted on her feelings for women, whether she wanted to, or whether she would have been able to, considering her society's prohibitions and her own inhibitions."

Käthe intended to continue her studies with Karl Stauffer-Bern but in 1888, Friedrich Welti, a very wealthy businessman, agreed to finance a stay in Rome for Stauffer-Bern. Soon afterwards, Stauffer-Bern, began a sexual relationship with his wife, Lydia Welti-Escher. When news of the relationship reached Welti, he used his government contacts to have Lydia committed to an asylum, and Stauffer-Bern was briefly sent to prison under trumped-up charges. On his release he committed suicide.

In 1888 Käthe went to study at the Munich Women's Art School. She also joined the informal Composition Club, that met at the Glücks-Café. Other members included Otto Greiner, Alexander Oppler and Gottlieb Elster. Käthe impressed fellow members when she exhibited for the first time at the club. The drawings were illustrations of a coal miner's strike. That night she wrote in her journal: "For the first time I felt that my hopes were confirmed; I imagined a wonderful future and was so filled with thoughts of glory and happiness that I could not sleep all night."

Käthe and Jeep also joined the Munich Etching Club. Later, Jeep described Käthe's first lesson: "The coal-black plate was now ready for drawing, so she found an empty table to work. Her right hand gripped the etching knife surely as she pressed it into the black wax. The manner in which she etched was much freer and more expressive than what they were used to; her etching looked more like a pen-and-ink drawing. Gradually the copper lines showed the face of an old man... The copper face shone out impressively from the blackened plate; she felt satisfied, and ready to etch... She continued to work industriously. Her style of secure and penetrating lines was already apparent."

Käthe continued to take a keen interest in politics. She was impressed with the work of Karl Kautsky, who was considered the best interpreter of the theories of Karl Marx. She spent a lot of time with fellow artist, Helene Bloch, who had a studio in Königsberg. She recorded in her journal that "we had weekly get-togethers in my studio during which we read Kautsky's popularization of Marx's ideas."

According to the author of Käthe Kollwitz (1976), Käthe gradually began to give up on painting: "By this time she was able to draw with pen, pencil, chalk, and charcoal; paint with ink and wash, and etch; but she could not lift the same scene intact onto canvas. Try as she might to perfect her painterly technique in the same way that she had mastered drawing and etching, she found that she had no feel for color or its great and subtle uses; nor did colour or nature inspire her in the same way as the lines and expressions of working people."

In 1891 Karl Kollwitz qualified as a doctor and obtained a position in a working-class area of Berlin. In a response to the growing support of the Social Democratic Party (SDP), Otto von Bismarck had introduced the first European system of health insurance in which accident, sickness, and old age expenses of the workers and their families were covered by a government health insurance. As a socialist, Karl wanted to serve the poor and this new legislation made this possible.

Karl Kollwitz now asked Käthe to marry him. Käthe recorded in her journal how disappointed her father had been by the news: "He had expected a much faster completion of my studies, and then exhibitions and success. Moreover, as I have mentioned, he was very skeptical about my intention to follow two careers, that of artist and wife." Shortly before her wedding on 13th June, 1891, her father told her, "You have made your choice now. You will scarcely be able to do both things. So be wholly what you have chosen to be."

The couple moved to an apartment on 25 Weissenburger Strasse, on the corner of Wörther Platz. Soon after they married Emma Jeep visited them: "Our attitude toward life was that of a child's: we still expected adventures. At the very first meeting with Käthe's husband, who now belongs to both of us, we laughted and laughed hysterically. We were taken by such a storm of laughter that we barely needed any reason or impulse to start us up again! Dr. Kollwitz was helpless. Finally he diagnosed it - and us - as fatigue, and told us that we should go to sleep. So we retreated to the big double bed, and the unstoppable laughter succumbed, after a while, to our dreams."

At first, Karl attracted very few patients. Käthe recorded: "We often stood at the window or on the tiny corner balcony, watching the passersby in the street below, hoping that one or other of them would find his way into the waiting-room." Next to Karl's office on the second floor was Käthe studio. It was a completely plain room as she liked to work without any visual distractions. Käthe drew numerous studies of hands; a young nude woman (probably Jeep); and some self-portraits.

In May, 1892, Käthe Kollwitz gave birth to her first child, a son, they called Hans. She soon began to use her son as a model. In his first few months she did eighteen drawings of him. Karl kept his promise and "did everything possible so that I would have time to work". She recalled that this "quiet, hardworking life" was "unquestionably good for my further development". As soon as they could afford it, a live-in housekeeper was hired to help her with her child-rearing duties.

In 1893 Käthe took part in a joint exhibition of Berlin artists. One leading art critic, Ludwig Pietsch, complained that the organisers had allowed a woman to exhibit. However, another critic, Julius Elias, wrote: "In almost every respect the talent of a young woman stands out. A young woman who will be able to bear the insult of this first rejection lightly, for she is assured of a rich artistic future. Frau Kollwitz perceives nature readily and intensely, using clear, well-formed lines. She is attracted to unusual light and deep colour tones. Hers is a very earnest display of artwork." Encouraged by these positive comments, Kollwitz began work on a series of drawings that illustrated the novel, Germinal.

On this day in 1882 suffrage campaigner Mary Adamson, the daughter of Robert Adamson and Daisy Duncan, was born. Robert Adamson came from a poor, working-class family, but he eventually became Professor of Logic and Metaphysics at Glasgow University. Mary's mother came from a Quaker family and had been one of the first women to become a student at Newnham College, Cambridge.

Robert and Daisy Adamson were both supporters of women's rights and were determined to raise their six children according to these principals. When Mary, the eldest daughter, had reached the age of eighteen, she was sent to Newnham College. At university she became friendly with Margery Corbett and together they joined the Cambridge branch of the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Mary spent many weekends at Margery's home in Danehill, Sussex, and was brought into contact with Marie Corbett, Cicely Corbett, and other committed feminists in Sussex.

Mary obtained a first class honours degree, and this enabled her to obtain a teaching post in the history department of the University College of South Wales. In 1905 she resigned her post after her marriage to a university colleague, Charles Hamilton.

Mary Hamilton remained an active member of the NUWSS and after her conversion to socialism, she joined the Independent Labour Party. On the outbreak of the First World War, she joined the Union for Democratic Control and became active in the struggle for a negotiated peace.

In 1920 Lady Margaret Rhondda, founded the political magazine Time and Tide. Mary became one of the journal's main contributors. She also worked as a journalist for The Economist magazine and edited Review of Reviews with Philip Gibbs.

In 1923 General Election Mary Hamilton made her first attempt to enter House of Commons. After the passing of the Equal Franchise Act in 1928, which gave all women over the age of twenty-one the vote, it became easier for women to be selected as candidates in winnable constituencies.

In the 1929 General Election Hamilton became Labour MP for Blackburn. Mary Hamilton was appointed as Parliamentary Private Secretary to Clement Attlee, the Postmaster General in the Ramsey MacDonad government. Mary also served on the Royal Commission on the Civil Service where she argued strongly in favour of equal pay for men and women. Mary also became involved in the campaign to remove the marriage bar on women teachers.

After her defeat in the 1931 General Election, Hamilton remained in public life. Mary was a governor of the BBC (1932-1936) and a member of the London County Council (1937-1940). During the Second World War Hamilton was head of the American Division of the Ministry of Information. Hamilton also wrote biographies of important labour figures such as Margaret Bondfield and Arthur Henderson.

Mary Hamilton died on 10th February, 1966.

On this day in 1899 Evelina Haverfield writes in her diary why she is not going to use her husband's name. "I married Major Balguy R.A. with no intention of changing my name or mode of life in any way. He is an old friend of my darling Jack's. The ceremony took place at Caundle Marsh Church in the presence of Mrs. C., my parlour boarder, and of Shepherd, my groom." Evelina reassumed the name "Haverfield" by deed poll within a month of the marriage. An excellent horsewomen, she accompanied her new husband husband to South Africa when he fought in the Boer War.

An early member of the National Union of Suffrage Societies she joined the Women's Social and Political Union in March 1908. She later explained that she joined the WSPU after hearing Minnie Baldock speak at a public meeting. Sylvia Pankhurst recalled: "When she first joined the Suffragette movement her expression was cold and proud... I was repelled when she told me she felt no affection for her children."

On this day in 1911 Emma Sproson is sent to prison for keeping a dog without a licence. Sproson was a member of the national executive committee of the Women's Freedom League. Like the Women's Social and Political Union, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. The WFL also attracted suffragettes who preferred to work with the Labour Party and "who regarded it as hypocritical for a movement for women'd democracy to deny democracy to its own members."

It was WFL policy of "no taxation without representation" meant that in 1911 Emma Sproson served two terms of imprisonment in Stafford gaol for the offence of keeping a dog without a licence. Frank Sproson wrote in The Vote: "The humiliating position of the married woman, especially the working woman, is admitted by all Suffragists; but I never realised that she was such an abject slave so clearly as when I stood in the Wolverhampton Police Court, side by side with my wife, charged with aiding and abetting her to keep a dog without a license. The only evidence submitted by the prosecution (the police) that I actually did anything was that I presided at two meetings in support of the "No Vote, No Tax" policy of the Women's Freedom League. That I said anything that was not fair comment on the general policy of militancy there was no evidence to show; if, then, on this point I was liable, then all supporters of militancy are equally so. But I do not believe it was on this evidence that I was convicted. No. The dog was at my house, and cared for by my children during my wife's absence. In the eyes of the law, I was lord and master, so that my offence, therefore, was not that I did anything, but rather that I did not do anything."

On this day in 1917 Alexander Kerensky becomes prime minister of Russia. Ariadna Tyrkova, a member of the Constitutional Democrat Party, commented: "Kerensky was perhaps the only member of the Government who knew how to deal with the masses, since he instinctively understood the psychology of the mob. Therein lay his power and the main source of his popularity in the streets, in the Soviet, and in the Government." Arthur Ransome reported: "Then, as on a dozen other occasions, Mr Kerensky saved the situation... It is no longer possible to accuse the Government of seeking Constantinople or, indeed, anything but the salvation and preservation of Russia and Russian free¬dom. For that purpose there is no party in the State unwilling to make the utmost effort."

The British ambassador, George Buchanan welcomed the appointment of Kerensky and reported back to London: "From the very first Kerensky had been the central figure of the revolutionary drama and had, alone among his colleagues, acquired a sensible hold on the masses. An ardent patriot, he desired to see Russia carry on the war till a democratic peace had been won; while he wanted to combat the forces of disorder so that his country should not fall a prey to anarchy. In the early stages of the revolution he displayed an energy and courage which marked him out as the one man capable of securing the attainment of these ends."

The journalist, Louise Bryant, interviewed Kerensky soon after he took office. She commented in her book, Six Months in Russia (1918): "I had a tremendous respect for Kerensky when he was head of the Provisional Government. He tried so passionately to hold Russia together, and what man at this hour could have accomplished that? He was never wholeheartedly supported by any group. He attempted to carry the whole weight of the nation on his frail shoulders, keep up a front against the Germans, keep down the warring political factions at home." Kerensky told John Reed: "The Russian people are suffering from economic fatigue and from disillusionment with the Allies! The world thinks the Russian Revolution is at an end. Do not be mistaken. The Russian Revolution is just beginning."

Alfred Knox, the British Military Attaché in Petrograd, also argued that he British should give full support to Kerensky: "There is only one man who can save the country, and that is Kerensky, for this little half-Jew lawyer has still the confidence of the over-articulate Petrograd mob, who, being armed, are masters of the situation. The remaining members of the Government may represent the people of Russia outside the Petrograd mob, but the people of Russia, being unarmed and inarticulate, do not count. The Provisional Government could not exist in Petrograd if it were not for Kerensky."

According to the American journalist, Lincoln Steffens: "Kerensky... turned for advice to his committee and to other prominent leaders, whose ideas had been formed in moderate, reform movements under the Czar. He was for a republic, a representative democracy, which in his mind was really a plutocratic aristocracy. Meanwhile he was to carry on the war. These were not the ideas of the mob in the street. The people were confused, too; they did not know what a republic was; democracy, as we have seen, was a literal impossibility; but they were definite and clear about peace and no empire. So Kerensky... represented the people emotionally, but not in ideas... he felt the revolution, which he named public opinion, sweeping him along and passing him by. Kerensky could not even manage that public opinion. There were other orators trying to do that, and the people listened to them as they did to Kerensky."

Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the head of MI6, decided that the British government should do everything possible to keep Alexander Kerensky in power. He contacted William Wiseman, their man in New York City and supplied Wiseman with $75,000 (approximately $1.2 million in modern prices) for Kerensky's Provisional Government. A similar sum was received from the Americans. Wiseman now approached Somerset Maugham (to whom he was related by marriage) in June 1917, to go to Russia. Maugham was "staggered" by the proposition: "The long and short of it was that I should go to Russia and keep the Russians in the war."

Kerensky was still the most popular man in the government because of his political past. In the Duma he had been leader of the moderate socialists and had been seen as the champion of the working-class. However, Kerensky, like George Lvov, was unwilling to end the war. In fact, soon after taking office, he announced a new summer offensive. Soldiers on the Eastern Front were dismayed at the news and regiments began to refuse to move to the front line. There was a rapid increase in the number of men deserting and by the autumn of 1917 an estimated 2 million men had unofficially left the army. Some of these soldiers returned to their homes and used their weapons to seize land from the nobility. Manor houses were burnt down and in some cases wealthy landowners were murdered. Kerensky and the Provisional Government issued warnings but were powerless to stop the redistribution of land in the countryside.

After the failure of the July Offensive on the Eastern Front, Kerensky replaced General Alexei Brusilov with General Lavr Kornilov, as Supreme Commander of the Russian Army. The two men soon clashed about military policy. Kornilov wanted Kerensky to restore the death-penalty for soldiers and to militarize the factories. On 7th September, Kornoilov demanded the resignation of the Cabinet and the surrender of all military and civil authority to the Commander in Chief. Kerensky responded by dismissing Kornilov from office and ordering him back to Petrograd. Kornilov now sent troops under the leadership of General Krymov to take control of Petrograd.

Kerensky was now in danger and so he called on the Soviets and the Red Guards to protect Petrograd. The Bolsheviks, who controlled these organizations, agreed to this request, but in a speech made by their leader, Lenin, he made clear they would be fighting against Kornilov rather than for Kerensky. Within a few days Bolsheviks had enlisted 25,000 armed recruits to defend Petrograd. While they dug trenches and fortified the city, delegations of soldiers were sent out to talk to the advancing troops. Meetings were held and Kornilov's troops decided to refuse to attack Petrograd. General Krymov committed suicide and Kornilov was arrested and taken into custody.

Somerset Maugham reached Petrograd in early September 1917. Somerset Maugham worked closely with Major Stephen Alley, the MI1(c) station chief in Petrograd. Maugham telegraphed Wiseman recommending a programme of propaganda and covert action. He also proposed setting up a "special secret organisations" recruited from Poles, Czechs and Cossacks with the main aim of "unmasking... German plots and propaganda in Russia".

Alexander Kerensky now became the new Supreme Commander of the Russian Army. His continued support for the war effort made him unpopular in Russia and on 8th October, Kerensky attempted to recover his left-wing support by forming a new coalition that included more Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries. However, with the Bolsheviks controlling the Soviets, and now able to call on 25,000 armed militia, Kerensky was unable to reassert his authority.

John Reed claimed that Kerensky made a serious mistake: "The Cossacks entered Tsarskoye Selo, Kerensky himself riding a white horse and all the church-bells clamouring. There was no battle. But Kerensky made a fatal blunder. At seven in the morning he sent word to the Second Tsarskoye Selo Rifles to lay down their arms. The soldiers replied they would remain neutral, but would not disarm. Kerensky gave them ten minutes in which to obey. This angered the soldiers; for eight months they had been governing themselves by committee, and this smacked of the old regime. A few minutes later Cossack artillery opened fire on the barracks, killing eight men. From that moment there were no more 'neutral' soldiers in Tsarskoye."

At a conference of the Constitutional Democratic Party on 22nd October, 1917, one of Kerensky's main rivals, Pavel Milyukov, was severely criticized. Melissa Kirschke Stockdale, the author of Paul Miliukov and the Quest for a Liberal Russia (1996) has argued that delegates "lashed out at Miliukov with unaccustomed ferocity. His travels abroad had made him poorly informed about the public mood, they charged; the patience of the people was exhausted." Miliukov defended his policies by arguing: "It will be our task not to destroy the government, which would only aid anarchy, but to instill in it a completely different content, that is, to build a genuine constitutional order. That is why, in our struggle with the government, despite everything, we must retain a sense of proportion.... To support anarchy in the name of the struggle with the government would be to risk all the political conquests we have made since 1905."

The Cadet party newspaper did not take the Bolshevik challenge seriously: "The best way to free ourselves from Bolshevism would be to entrust its leaders with the fate of the country... The first day of their final triumph would also be the first day of their quick collapse." Leon Trotsky accused Milyukov of being a supporter of General Lavr Kornilov and trying to organize a right-wing coup against the Provisional Government.

Alexander Kerensky later claimed he was in a very difficult position and described Milyukov's supporters as beings Bolsheviks of the Right: "The struggle of the revolutionary Provisional Government with the Bolsheviks of the Right and of the Left... We struggled on two fronts at the same time, and no one will ever be able to deny the undoubted connection between the Bolshevik uprising and the efforts of Reaction to overthrow the Provisional Government and drive the ship of state right onto the shore of social reaction." Kerensky argued that Milyukov was now working closely with General Lavr Kornilov and other right-wing forces to destroy the Provisional Government: "In mid-October, all Kornilov supporters, both military and civilian, were instructed to sabotage government measures to suppress the Bolshevik uprising."

On 31st October 1917 Somerset Maugham was summoned by Kerensky and asked to take an urgent secret message to David Lloyd George appealing for guns and amununition. Without that help, said Kerensky, "I don't see how we can go on. Of course, I don't say that to the people. I always say that to the people. I always say that we shall continue whatever happens, but unless I have something to tell my army it's impossible". Maugham was unimpressed by Kerensky: "His personality had no magnetism. He gave no feeling of intellectual or of physical vigour."

Maugham left the same evening for Oslo to board a British destroyer which, after a stormy passage across the North Sea, landed him in the north of Scotland. Next morning he saw Lloyd George at 10 Downing Street. After the agent told the Prime Minister what Kerensky wanted, he replied: "I can't do that. I'm afraid I must bring this conversation to an end. I have a cabinet meeting I must go to."

On 7th November, Kerensky was informed that the Bolsheviks were about to seize power. He decided to leave Petrograd and try to get the support of the Russian Army on the Eastern Front. Later that day the Red Guards stormed the Winter Palace and members of the Kerensky's cabinet were arrested. Kerensky assembled loyal troops from the Northern Front but his army was defeated by Bolshevik forces at Pulkova.

Morgan Philips Price explained in the Manchester Guardian on 19th November, 1917, why the government of Alexander Kerensky fell: "The Government of Kerensky fell before the Bolshevik insurgents because it had no supporters in the country. The bourgeois parties and the generals and the staff disliked it because it would not establish a military dictatorship. The Revolutionary Democracy lost faith in it because after eight months it had neither given land to the peasants nor established State control of industries, nor advanced the cause of the Russian peace programme. Instead it brought off the July advance without any guarantee that the Allies had agreed to reconsider war aims. The Bolsheviks thus acquired great support all over the country. In my journey in the provinces in September and October I noticed that every local Soviet had been captured by them."

Kerensky remained underground in Finland until escaping to London in May 1918. He later moved to France where he led the propaganda campaign against the communist regime in Russia. This included editing the Russian newspaper, Dni, that published in Paris and Berlin. In 1939 Kerensky urged the western democracies to intervene against both communism in the Soviet Union and fascism in Germany.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Kerensky moved to the United States. He worked at the Hoover Institution in California and wrote his autobiography, The Kerensky Memoirs: Russia and History's Turning Point (1967).

Alexander Kerensky died of cancer in New York on 11th June, 1970.

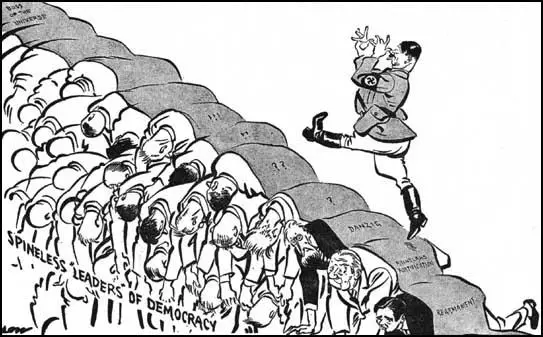

On this day in 1936 David Low attacks "spineless appeasers". On 8th July, 1936, Low produced a powerful attack on Anthony Eden and other European leaders failed to respond to the aggressive foreign policy of Adolf Hitler: "When German troops reoccupied the Rhineland demilitarized zone, Hitler justified the breach of the Versailles and Locarno Treaties by asserting that both were already dead. He had, he said, a peace-plan of his own to take their place - a 25-year Western non-aggression pact. When Eden, to the anxious interest of Van Zeeland (Belgium), Flandin (France), Litvinov (Russia), Titulescu (Rumania) and others, asked for the precise meaning of vague and ambiguous details, Hitler evaded reply."

This was followed by another cartoon that attacked the way the politicians dealt with Hitler's decision to reoccupy the Rhineland. "Both the rearming of Germany and the reoccupation of the Rhineland caught Western statesmanship off balance between the French policy of resistance to Germany and persuasion to Italy and the British policy of resistance to Italy and persuasion to Germany. The German General Staff had been unable to make war, but Hitler gambled on there being no resistance from the French without British support. When he was proved right, and leaders of both democracies still refused to accept the risk, his generals were impressed by his intuition".

In September, 1937, Percy Cudlipp, the editor of Evening Standard, started refusing to publish Low's cartoons attacking Hitler: "The state of Europe is extremely tense at the present time. That being so, I don't want to publish anything in the Evening Standard which would add to the tension, or inflame tempers any more than they are already inflamed. There are people whose tempers are inflamed more by a cartoon than by any letterpress. So will you please, when you are planning your cartoons, bear in mind my anxiety on this score."

Low's cartoons criticizing Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini resulted in his work being banned in Germany and Italy. After the war it was revealed that in 1937 the German government asked the British government to have "discussions with the notorious Low" in an effort to "bring influence to bear on him" to stop his cartoons attacking appeasement. Lord Halifax, the foreign secretary, went to see Low: "When Lord Halifax visited Germany officially in 1937, he was told that the Führer was deeply offended by Low's cartoons of him, and that the paper in which they appeared, the Evening Standard, was banned in Germany.... On Halifax's return to London, he summoned Low and told him that his cartoons were impairing the prime minister's policy of appeasement."

On this day in 1939 Havelock Ellis died at Cherry Ground, Hintlesham, near Ipswich. His autobiography, My Life, was published posthumously during the Second World War in 1940. His biographer, Phyllis Grosskurth, has pointed out: "It was a great disappointment in terms of sales or critical reception. In 1940 people's minds were too preoccupied with the war to pay much attention to it and the reviews tended to be either patronizing or outraged by the accounts of Edith's lesbianism and Ellis's urolagnia."

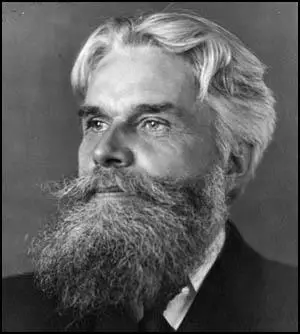

Henry Havelock Ellis, the eldest child and only son of Edward Peppern Ellis (1827–1914), a sea captain, and his wife, Susannah Mary (1829–1888), was born on 2nd February 1859 at 1 St John's Grove, Croydon. He was named after a distant relation, Sir Henry Havelock, a general during the Indian Mutiny.

His father was rarely home and it was his mother who was the dominant influence in his early life. According to one of his biographers: "As an ardent evangelical Christian, who had experienced a conversion at the age of seventeen, she had vowed never to visit a theatre in her life. Despite this she was a warm influence on the young Ellis, who early on slipped away from the more rigid aspects of her faith." Havelock Ellis was provided with a basic education at local schools but he was a compulsive reader and he was deeply influenced by the philosopher, Ernest Renan, and the poets, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Algernon Charles Swinburne.

He travelled with his father to Australia and at the age of nineteen became a teacher in schools in the outback. During this period he read Life in Nature by James Hinton, a writer on political, social, religious, and sexual matters. He later recalled that the book sparked a spiritual transformation: "The clash in my inner life was due to what had come to seem to me the hopeless discrepancy of two different conceptions of the universe … The great revelation brought to me by Hinton … was that these two conflicting attitudes are really but harmonious though different aspects of the same unity." Ellis now became convinced that sexual freedom could bring in a new age of happiness.

Havelock Ellis arrived back in England in April 1879 and eventually became a medical student at St Thomas's Hospital in Southwark. In 1883 he joined the Fellowship of the New Life, an organisation founded by Thomas Davidson. Other members included Edward Carpenter, Edith Lees, Edith Nesbit, Frank Podmore, Isabella Ford, Henry Hyde Champion, Hubert Bland, Edward Pease and Henry Stephens Salt. According to another member, Ramsay MacDonald, the group were influenced by the ideas of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In January 1884 some of the members of the group, including Havelock Ellis, decided to form a socialist debating group. Frank Podmore suggested that the group should be named after the Roman General, Quintus Fabius Maximus, who advocated the weakening the opposition by harassing operations rather than becoming involved in pitched battles. They therefore decided to call themselves the Fabian Society.

Havelock Ellis read the novel Story of an African Farm at the beginning of 1884. He wrote in his autobiography, My Life (1940): "What delighted me in The African Farm was, in part, the touch of genius, the freshness of its outlook, the firm splendor of its style, the penetration of its insight into the core of things." Ellis wrote to the author, Olive Schreiner and she replied on 25th February 1884: "The book was written in an upcountry farm in the Karoo and it gives me great pleasure to think that other hearts find it real." Soon afterwards they arranged a meeting and over the next few months they were constant companions.

Phyllis Grosskurth, the author of Havelock Ellis (1980), has argued: "Ellis and Olive were completely devoted to each other. They went to meetings and lectures together; they wandered through art galleries; late at night after the theatre they would stroll along the street, the tall, lean youth and the short, squat girl holding hands and chattering endlessly in a carefree way." They both shared the same views on sexuality, free love, marriage, the emancipation of women, sexual equality and birth control.

Ellis later wrote in his autobiography, My Life (1940): "She was in some respects the most wonderful woman of her time, as well as its chief woman-artist in language, and that such a woman should be the first woman in the world I was to know by intimate revelation was an overwhelming fact. It might well have disturbed my mental balance, and for a while I was almost intoxicated by the experience." However, he added: "We were not what can be technically, or even ordinarily, called lovers. But the relationship of affectionate friendship which was really established meant more for both of us, and was even more intimate, than is often and relationship between those who technically and ordinarily are lovers."

According to Jeffrey Weeks: "Olive was a forceful and passionate woman, though prone to ill health, and the two writers quickly established a fervent relationship. It is not clear whether it was conventionally consummated. Ellis himself appears not to have been strongly drawn to heterosexual intercourse, and had a lifelong interest in urolagnia, a delight in seeing women urinate."

Olive also became friends with Karl Pearson, the Goldsmid Chair of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics at University College. By 1885 she was in love with Pearson and he began to replace Havelock Ellis in the role of confidant. However, he did not feel the same way about her. Olive wrote that while she was desperately in love, he was "too idealistic for anything as earthy as sex." He later married Maria Sharpe and their relationship came to an end.

Olive Schreiner remained close to Ellis but was upset by his lack of sexual desire. She wrote to Edward Carpenter: "Ellis has a strange reserved spirit. The tragedy of his life is that the outer man gives no expression to the wonderful beautiful soul in him, which now and then flashes out on you when you come near him. In some ways he has the noblest nature of any human being I know."

By March 1884 the Fabian Society had twenty members. However, over the next couple of years the group increased in size and included socialists such as Sydney Olivier, William Clarke, Eleanor Marx, Annie Besant, Graham Wallas, J. A. Hobson, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw, Charles Trevelyan, J. R. Clynes, Harry Snell, Clementina Black, Walter Crane, Sylvester Williams, H. G. Wells, Clifford Allen and Amber Reeves.

Havelock Ellis met Edith Lees, in 1887 at a meeting of the Fellowship of the New Life. He later recalled: "She was a small, compact, active person, scarcely five feet in height, with a fine skin, a singularly well-shaped head with curly hair, square, powerful hands, very small feet, and - her most conspicuous feature on a first view - large rather pale blue eyes. I cannot say that the impression she made on me on that occasion was specially sympathetic; it so happens that the dominating feature of her face, the pale blue eyes, is not one that appeals to me, for to me green or grey eyes (I believe because one is drawn to those of one's own type) are the congenial eyes, and I never grew really to admire them, though to many they were peculiarly beautiful and fascinating." Edith was also critical of Havelock's appearance. "She (Edith) was not impressed; it seemed to her that my clothes were ill-made, and that was a point on which she always remained sensitive."

In 1890 Havelock Ellis' first book, The New Spirit, was published. According to one critic, the book discusses "the manifestations of the new spirit abroad in the world: the growing sciences of anthropology, sociology, and political science; the increasing importance of women; the disappearance of war; the substitution of art for religion as a social and emotional outlet." The book was heavily criticised. One reviewer commented that: "His reading has been rather too exclusively among the rebels and heretics of literature; and he would be well advised if he were to restore the balance by devoting more attention to the older, more conservative, more historic writers, whose influence, we may depend upon it, will survive the fame of several of the new men for whom our present-day critics are erecting very lofty pedestals."

Edith Lees later wrote: "When I first read The New Spirit, I knew I loved the man who wrote it." In August, Ellis had a week's work replacing Dr. Bonar at Probus, in Cornwall. While Lamorna he met Edith Lees who was on holiday at the time. They went for long walks together and talked a great deal about their ideas on politics and religion. Ellis later described their relationship as "a union of affectionate comradeship, in which the specific emotions of sex had the smallest part, yet a union, as I was later to learn by experience, able to attain even on that basis a passionate intensity of love."

They eventually married on 19th December 1891. The relationship was highly unconventional. They maintained separate incomes and, for large parts of the year, separate dwellings. It seems that they did not have a sexual relationship. Ellis wrote that "on my side I felt that in this respect we were relatively unsuited to each other, that (sexual) relations were incomplete and unsatisfactory". Lees was a lesbian who had relationships with other women. The first relationship was with a woman that Ellis called "Claire" in his autobiography. Phyllis Grosskurth has pointed out: "Edith was to have a succession of passionate relationships, although - and Ellis regarded this as an extenuation - only one intense friend at a time. He learned to accept the succession of dear friends; he never quarrelled with any of them and the only test he applied to them was whether they were good for Edith or not."

According to Lillian Faderman, the author of Surpassing the Love of Men (1985): "Ellis's wife, Edith Lees, seems to have been a victim of his theories. From his own account, Ellis apparently convinced her that she was a congenital invert (lesbian), while she believed herself to be only a romantic friend to other women. He relates in My Life that during the first years of their marriage, she revealed to him an emotional relationship with an old friend who staved with her while she and Ellis were apart... He thus encouraged her to see herself as an invert and to regard her subsequent love relations with women as a manifestation of her inversion."

In his autobiography, My Life: Havelock Ellis claimed: "It was certainly not a union of unrestrainable passion; I, though I failed yet clearly to realise why, was conscious of no inevitably passionate sexual attraction to her, and she, also without yet clearly realising why, had never felt genuinely passionate sexual attraction for any man... Whatever passionate attractions she had experienced were for women."

Havelock Ellis published his second book, The Nationalization of Health in 1892. Phyllis Grosskurth has commented that Ellis argued: "The state was to be responsible for the physical well-being of the individual, a revolutionary suggestion in its time. Against an historical background of the development of health movements, he discusses the role of the private practitioner, the existing hospital system, the hospital of the future, and the necessity for a Minister of Health... In The Nationalization of Health a national health scheme is, as far as I know, advocated for the first time."

In 1894 Ellis published Man and Woman: A Study of Human Secondary Sexual Characters. In his autobiography he wrote "it was a book to be studied and read in order to clear the ground for the study of sex in the central sense in which I was chiefly concerned with it". He added that it was "primarily undertaken for my own edification". However, as the author of Havelock Ellis (1980) has pointed out: "Until his marriage to Edith, Olive Schreiner seems to have been the only woman with whom he indulged in sexual intimacies, however unsatisfactory they may have been. In other words, the man who wrote Man and Woman was almost totally inexperienced, and when he departs from physiological description he sounds remarkably naïve."

In 1897 Havelock Ellis published Sexual Inversion, the first of his six volume Studies in the Psychology of Sex. The book was first serious study of homosexuality published in Britain. It was based partly as a result of his awareness of the homosexuality of his wife and friends such as Edward Carpenter. Ellis admitted in his autobiography: "Homosexuality was an aspect of sex which up to a few years before had interested me less than any, and I had known very little about it. But during those few years I had become interested in it. Partly I had found that some of my most highly esteemed friends were more or less homosexual (like Edward Carpenter, not to mention Edith)." According to a letter he wrote to Arthur Symonds, Edith Lees Ellis promised to "supply cases of inversion (homosexuality) in women from among her own friends."

Phyllis Grosskurth has argued: "Sexual Inversion was an unprecedented book. Never before had homosexuality been treated so soberly, so comprehensively, so sympathetically. To read it today is to read the voice of common sense and compassion; to read it then was, for the great majority, to be affronted by a deliberate incitement to vice of the most degrading kind.... That such sexual proclivity is not determined by suggestion, accident, or historical conditioning is apparent, he argues, from the fact that it is widespread among animals and that there is abundant evidence of its prevalence among various nations at all periods of history."

As one biographer, Jeffrey Weeks, pointed out: "Ellis's aim was to demonstrate that homosexuality (or inversion, his preferred term) was not a product of peculiar national vices, or periods of social decay, but a common and recurrent part of human sexuality, a quirk of nature, a congenital anomaly." This idea was repugnant to most people and the book was attacked by most reviewers. The birth-control campaigner, Marie Stopes, described reading it as "like breathing a bag of soot; it made me feel choked and dirty for three months."

George Bedborough, the secretary of the Legitimation League, was arrested on 31st May 1898 and charged with selling Sexual Inversion. The arresting officer, John Sweeney, later admitted that the objective was to destroy what they believed was an anarchist organisation as well as removing obscene books for sale: "we were convinced that we should at one blow kill a growing evil in the shape of a vigorous campaign of free love and Anarchism, and at the same time discover the means by which the country was being flooded with books of the psychology type." Bedborough was charged with having "sold and uttered a certain lewd wicked bawdy scandalous and obscene libel in the form of a book entitled Studies in the Psychology of Sex: Sexual Inversion."

A group including George Bernard Shaw, Henry Hyndman, Frank Harris and George Moore, formed a committee to defend the book. Shaw argued: "The prosecution of Mr. Bedborough for selling Mr. Havelock Ellis's book is a masterpiece of police stupidity and magisterial ignorance... In Germany and France the free circulation of such works as the one of Mr. Havelock Ellis's now in question has done a good deal to make the public in those countries understand that decency and sympathy are as necessary in dealing with sexual as with any other subjects. In England we still repudiate decency and sympathy and make virtues of blackguards and ferocity."

In court the book was described as being a "certain lewd, wicked, bawdy, scandalous libel". The judge told George Bedboroug: "So long as you do not touch this filthy work again with your hands and so long as you lead a respectable life, you will hear no more of this. But if you choose to go back to your evil ways, you will be brought up before me, and it will be my duty to send you to prison for a very long time." As a result of this case all copies of Sexual Inversion were withdrawn from sale.

In 1898 Edith Lees Ellis published her first novel, Seaweed: A Cornish Idyll. Havelock Ellis commented that the novel was "a real work of art, well planned and well balanced, original and daring, the genuinely personal outcome of its author, alike in its humour and its firm, deep grip of the great sexual problems it is concerned with, centering around the relations of a wife to a husband who by accident has become impotent.... it has seemed to me that the story was consciously or unconsciously inspired by her own relations with me and of course completely transformed by the artist's hand into a new shape."

During this period Edith began a relationship with Lily, an artist from Ireland who lived in St. Ives. In his autobiography, My Life, Ellis pointed out that: "Much as Edith always admired the clean, honest, reliable Englishwoman, there was yet, as I have already indicated, something in that type that was apt to jar on her in intimate intercourse; she craved something more gracious, less prudish, pure by natural instinct rather than by moral principle. In Lily she found the ideal embodiment of all her cravings." He claimed that he did not mind Edith's passionate relationship with Lily because Claire had absorbed all his capacity for jealously. Edith was devastated when Lily died from Bright's Disease in June 1903.

Havelock Ellis continued to work on Studies in the Psychology of Sex. Volume II, The Evolution of Modesty, The Phenomena of Sexual Periodicity, Auto-Erotism, appeared in 1899. This was followed by Love and Pain, The Sexual Impulse in Women (1903), Sexual Selection in Man (1905), Erotic Symbolism, The Mechanism of Detumescence (1906) and Sex in Relation to Society (1910).

Bertrand Russell wrote to Ottoline Morrell after the final volume was published: "I have read a good deal of Havelock Ellis on sex. It is full of things that everyone ought to know, very scientific and objective, most valuable and interesting. What a folly it is the way people are kept in ignorance on sexual matters, even when they think they know every-thing. I think almost all civilized people are in some way what would be thought abnormal, and they suffer because they don't know that really ever so many people are just like them."

In Erotic Symbolism, The Mechanism of Detumescence Havelock Ellis discussed his "own germ of perversion" urolagina: "There is ample evidence to show that, either as a habitual or more usually an occasional act, the impulse to bestow a symbolic value on the act of urination in a beloved person, is not extremely uncommon; it has been noted of men of high intellectual distinction; it occurs in women as well as men; when existing in only a slight degree, it must be regarded as within the normal limits of variation of sexual emotion."

In December 1914 Havelock Ellis received a letter from Margaret Sanger. As Phyllis Grosskurth, the author of Havelock Ellis (1980), has pointed out: "He invited her to tea the following week and was startled to find her so pretty and so comparatively young. At first she was overwhelmed by his patriarchal beauty and his refusal to make small talk. She was also surprised - as many others were on first meeting him - by his thin, high voice, so unexpected in a man of his size."

Sanger fell in love with Ellis. She wrote in An Autobiography (1938): "I was at peace, and content as I had never been before... I was not excited as I went back through the heavy fog to my own dull little room. My emotion was too deep for that. I felt as though I had been exalted into a hitherto undreamed-of world."

Soon afterwards Sanger tried to turn it into a sexual relationship. Ellis wrote to her explaining "What I felt, and feel, is that by just being your natural spontaneous self you are giving me so much more than I can hope to give you. You see, I am an extremely odd, reserved, slow undemonstrative person, whom it takes years and years to know. I have two or three very dear friends who date from 20 or 25 years back (and they like me better now than they did at first) and none of recent date."

Edith Lees Ellis suffered from poor health in her forties. In March 1916 she suffered from a severe nervous breakdown and entered a local convent nursing home at Hayle in Cornwall. Soon afterwards she attempted suicide by throwing herself from the fourth floor. Havelock Ellis wrote to Edward Carpenter: "Quite what she was feeling and thinking these last few days I do not know. It was some kind of despair. She has been despondent and self-reproachful as not having lived up to her ideals for some time past, and has lost her faith in things and in her spirit... The condition has been fundamentally neurasthenia, with mental symptoms - distressing loss of will power and helplessness."

Edith was eventually released but was forced back to hospital and died of diabetes in September 1916. Havelock Ellis told Margaret Sanger: She was always a child, and through everything, a very lovable child, to the last. Even friends whom she only made during the last few weeks are inconsolable at her loss." Two years later he arranged for the publication of her James Hinton: a Sketch (1918).

Françoise Lafitte-Cyon had been doing some translating work for Edith shortly before her death. Havelock first met her to pay an outstanding bill. They began meeting and on 3rd April 1918, Françoise, who was twenty years his junior, declared her love for the older man. Havelock wrote back that "I feel sure that I am good for you, and I am sure that you suit me. But as lover or a husband you would find me very disappointing." Havelock's relationship with Françoise blossomed. Stella Browne wrote to Margaret Sanger that "Ellis is looking better than I've seen him for some time: he seems slowly recovering from all he had to go through last year." They eventually moved into a cottage in Wivelsfield Green.

During the First World War Havelock's great friend, Olive Schreiner, returned to England. They saw each other often but it was not now a romantic relationship. According to Phyllis Grosskurth, the author of Havelock Ellis (1980): "Olive Schreiner... had become grotesquely fat, was obviously seriously ill, and was convinced that she did not have long to live." Sensing that death was imminent she returned to South Africa where she died following a heart-attack at her home in Wynberg on 10th December, 1920.

Havelock wrote to Françoise Lafitte-Cyon about her death: "I have for a very long time been reconciled to the idea of her (Olive Schreiner) death for I knew for many years her health had been undermined and how much she suffered. I am sure she was quite reconciled herself, though still so full of vivid interest in life, that she went back to Africa to die... It is the end of a long chapter in my life & your Faun will soon be left alone by all the people who knew him early in life."

In 1920 William Heinemann asked Ellis to write a preface for the German best seller, The Diary and Letters of Otto Braun. He was a poet and scholar who had been killed during the First World War. He was visited by Ella Winter, the translator of the book. She wrote in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "He was an astonishing old man, extremely tall and imposing, with a large head, white hair, and a bushy square beard. He lived alone in a small flat and, to my surprise, made the tea and carried in the tray." Ellis told her: "My wife lives in another flat, we feel that's better for our relationship." Winter pointed out: "When he discussed marriage, I kept very still lest he stop, but I was uncomfortable because he kept his eyes glued on the opposite wall and did not look at me. He developed this habit, I supposed, when he interviewed women about their sex lives for his Psychology of Sex. Presumably one talked more freely that way, but it gave me an eerie feeling. He did not ask me about my sex life. I was rather hurt."

Havelock Ellis published several more books including The Erotic Rights of Women (1918), The Philosophy of Conflict (1919), The Dance of Life (1923), Eonism and Other Supplementary Studies (1928), Fountain of Life (1930), The Revaluation of Obscenity (1931), The Psychology of Sex (1933), Questions of Our Day (1936) and Morals, Manners and Men (1939).