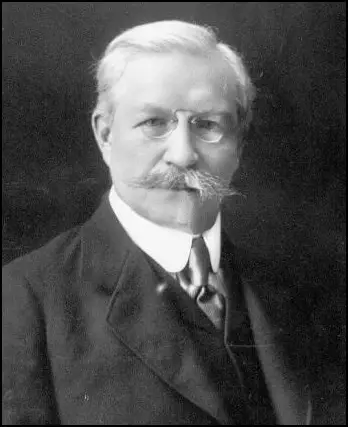

Pavel Milyukov

Pavel Milyukov, the son of an architect, was born in Moscow on 15th January, 1859. He studied history at the Moscow University but was expelled for taking part in student riots. Milyukov later returned to take his degree.

Milyukov, a specialist in Russian history, lectured at the university. Milyukov believed strongly in a democratic state and his opposition to the autocratic rule of Tsar Alexander III resulted in him being dismissed from office in 1894. His first book, Outlines of Russian Culture, appeared in 1896. His friend, Ariadna Tyrkova, explained: "The Tsar’s Government regarded P.N. Milyukov with great suspicion, and he was forbidden to lecture or to reside in university towns. He himself gradually abandoned scientific research and gave himself up to politics, preferring to make history rather than to study it."

Milyukov was arrested and spent six months in prison after making a political speech that the authorities disliked. On his release he was appointed professor of history at the University of Sofia. Milyukov remained active in politics and contributed to the radical journal, Liberation.

In 1905 Tsar Nicholas II faced a series of domestic problems that became known as the 1905 Revolution. This included Bloody Sunday, the Potemkin Mutiny and a series of strikes that led to the establishment of the St. Petersburg Soviet. Over the next few weeks over 50 of these soviets were formed all over Russia.

Sergi Witte, the new Chief Minister, advised Nicholas II to make concessions. He eventually agreed and published the October Manifesto. This granted freedom of conscience, speech, meeting and association. He also promised that in future people would not be imprisoned without trial. Finally he announced that no law would become operative without the approval of a new organization called the Duma. Milyukov now returned to Russia and established the Constitutional Democratic Party (Cadets) and represented it in the State Duma. He also drafted the Vyborg Manifesto that called for more political freedom.

During this period Russian government considered Germany to be the main threat to its territory. This was reinforced by Germany's decision to form the Triple Alliance. Under the terms of this military alliance, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy agreed to support each other if attacked by either France or Russia. In 1907 Russia joined Britain and France to form the Triple Entente.

On the outbreak of the First World War Milyukov began promoting patriotic policies of national defense, insisting his younger son volunteer for the army (he was later killed on the Eastern Front). In 1914 the Russian Army was the largest army in the world. However, Russia's poor roads and railways made the effective deployment of these soldiers difficult. By December, 1914, the army had 6,553,000 men. However, they only had 4,652,000 rifles. Untrained troops were ordered into battle without adequate arms or ammunition. In 1915 Russia suffered over 2 million casualties and lost Kurland, Lithuania and much of Belorussia. Agricultural production slumped and civilians had to endure serious food shortages.

In September 1915, Nicholas II replaced Grand Duke Nikolai as supreme commander of the Russian Army fighting on the Eastern Front. This failed to change the fortunes of the armed forces and by the end of the year there were conscription riots in several cities. Milyukov now began criticizing the government for its inefficiency.

General Alexei Brusilov, commander of the Russian Army in the South West, led an offensive against the Austro-Hungarian Army in June, 1916. Initially Brusilov achieved considerable success and in the first two weeks his forces advanced 80km and captured 200,000 prisoners. The German Army sent reinforcements to help their allies and gradually the Russians were pushed back. When the offensive was called to a halt in the autumn of 1916, the Russian Army had lost almost a million men.

On 26th February Nicholas II ordered the Duma to close down. Members refused and they continued to meet and discuss what they should do. Michael Rodzianko, President of the Duma, sent a telegram to the Tsar suggesting that he appoint a new government led by someone who had the confidence of the people. When the Tsar did not reply, the Duma nominated a Provisional Government headed by Prince George Lvov. Milyukov was appointed Foreign Minister, Alexander Guchkov, Minister of War, Alexander Kerensky, Minister of Justice, Mikhail Tereshchenko, a beet-sugar magnate from the Ukraine, became Finance Minister, Alexander Konovalov, a munitions maker, Minister of Trade and Industry and Peter Struve, Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Soon after taking power Milyukov wrote to all Allied ambassadors describing the situation since the change of government: "Free Russia does not aim at the domination of other nations, or at occupying by force foreign territories. Its aim is not to subjugate or humiliate anyone. In referring to the "penalties and guarantees" essential to a durable peace the Provisional Government had in view reduction of armaments, the establishment of international tribunals, etc." He attempted to maintain the Russian war effort but he was severely undermined by the formation of soldiers' committee that demanded "peace without annexations or indemnities".

As Robert V. Daniels, the author of Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967) pointed out: "On the 20th April, Milyukov's note was made public, to the accompaniment of intense popular indignation. One of the Petrograd regiments, stirred up by the speeches of a mathematician who happened to be serving in the ranks, marched to the Marinsky Palace (the seat of the government at the time) to demand Milyukov's resignation." With the encouragement of the Bolsheviks, the crowds marched under the banner, "Down with the Provisional Government".

Ariadna Tyrkova, a member of the Cadets, argued: "A man of rare erudition and of an enormous power for work, Milyukov had numerous adherents and friends, but also not a few enemies. He was considered by many as a doctrinaire on account of the stubbornness of his political views, while his endeavours to effect a compromise for the sake of rallying larger circles to the opposition were blamed as opportunism. As a matter of fact almost identical accusations were showered upon him both from Right and Left. This may partly be explained by the fact that it is easier for Milyukov to grasp an idea than to deal with men, as he is not a good judge of either their psychology or their character."

On 5th May, Milyukov and Alexander Guchkov, the two most conservative members of the Provisional Government, were forced to resign. Guchkov was now replaced as Minister of War by Alexander Kerensky. He toured the Eastern Front where he made a series of emotional speeches where he appealed to the troops to continue fighting. On 18th June, Kerensky announced a new war offensive. Encouraged by the Bolsheviks, who favoured peace negotiations, there were demonstrations against Kerensky in Petrograd.

At a conference of the Constitutional Democratic Party on 22nd October, 1917, Miliukov was severely criticized. Melissa Kirschke Stockdale, the author of Paul Miliukov and the Quest for a Liberal Russia (1996) has argued that delegates "lashed out at Miliukov with unaccustomed ferocity. His travels abroad had made him poorly informed about the public mood, they charged; the patience of the people was exhausted." Miliukov defended his policies by arguing: "It will be our task not to destroy the government, which would only aid anarchy, but to instill in it a completely different content, that is, to build a genuine constitutional order. That is why, in our struggle with the government, despite everything, we must retain a sense of proportion.... To support anarchy in the name of the struggle with the government would be to risk all the political conquests we have made since 1905."

The Cadet party newspaper did not take the Bolshevik challenge seriously: "The best way to free ourselves from Bolshevism would be to entrust its leaders with the fate of the country... The first day of their final triumph would also be the first day of their quick collapse." Leon Trotsky accused Milyukov of being a supporter of General Lavr Kornilov and trying to organize a right-wing coup against the Provisional Government.

Alexander Kerensky later claimed he was in a very difficult position and described Milyukov's supporters as beings Bolsheviks of the Right: "The struggle of the revolutionary Provisional Government with the Bolsheviks of the Right and of the Left... We struggled on two fronts at the same time, and no one will ever be able to deny the undoubted connection between the Bolshevik uprising and the efforts of Reaction to overthrow the Provisional Government and drive the ship of state right onto the shore of social reaction." Kerensky argued that Milyukov was now working closely with General Lavr Kornilov and other right-wing forces to destroy the Provisional Government: "In mid-October, all Kornilov supporters, both military and civilian, were instructed to sabotage government measures to suppress the Bolshevik uprising."

On 24th October Lenin wrote a letter to the members of the Central Committee: "The situation is utterly critical. It is clearer than clear that now, already, putting off the insurrection is equivalent to its death. With all my strength I wish to convince my comrades that now everything is hanging by a hair, that on the agenda now are questions that are decided not by conferences, not by congresses (not even congresses of soviets), but exclusively by populations, by the mass, by the struggle of armed masses… No matter what may happen, this very evening, this very night, the government must be arrested, the junior officers guarding them must be disarmed, and so on… History will not forgive revolutionaries for delay, when they can win today (and probably will win today), but risk losing a great deal tomorrow, risk losing everything."

On the evening of 24th October, orders were given for the Bolsheviks to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The following day the Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Kerensky had managed to escape from the city. The Winter Palace was defended by Cossacks, some junior army officers and the Woman's Battalion. At 9 p.m. the Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress began to open fire on the palace. Little damage was done but the action persuaded most of those defending the building to surrender. The Red Guards, led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, now entered the Winter Palace and arrested the Cabinet ministers. On 26th October, 1917, the All-Russian Congress of Soviets met and handed over power to the Soviet Council of People's Commissars.

After the Russian Revolution he advised leaders of the White Army. Following their defeat he emigrated to France, where he remained active in politics and edited the Russian-language newspaper Latest News. Several attempts were made to assassinate Milyukov. In one attempt in 1922, his friend Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, the father of famous novelist Vladimir Nabokov, was killed while with Milyukov.

Pavel Milyukov died in Aix-les-Bains on 31st March 1943.

Primary Sources

(1) Ariadna Tyrkova, From Liberty to Brest-Litovsk (1918)

All rejoiced at having got rid of mercenary, dishonest nonentities, like the Ministers Sukhomlinov or Protopopov, and were glad to see an irreproachably honest patriot, such as Prince G. Lvov always was and will be, placed at last at the head of the Russian Government. Among the members of the Government Paul Milyukov was the one who possessed the most strongly marked political individuality. He was a historian, and his works on the history of Russian culture are still looked upon as leading studies in the subject. But his academic career was soon ended. The Tsar’s Government regarded P.N. Milyukov with great suspicion, and he was forbidden to lecture or to reside in university towns. He himself gradually abandoned scientific research and gave himself up to politics, preferring to make history rather than to study it. Milyukov took an energetic part in the Constitutional movement, when it still bore a conspirative character (before the Treaty of Portsmouth), and after the first revolution in 1905 became one of the leaders of the newly formed Constitutional-Democratic (Cadet) party.

He became the leader of the opposition in the Third and Fourth Dumas, and his speeches caused far greater irritation in Government circles than did the sharper but narrowly Socialistic speeches of the extreme Left orators.

A man of rare erudition and of an enormous power for work, Milyukov had numerous adherents and friends, but also not a few enemies. He was considered by many as a doctrinaire on account of the stubbornness of his political views, while his endeavours to effect a compromise for the sake of rallying larger circles to the opposition were blamed as opportunism. As a matter of fact almost identical accusations were showered upon him both from Right and Left. This may partly be explained by the fact that it is easier for Milyukov to grasp an idea than to deal with men, as he is not a good judge of either their psychology or their character.

Not merely able but honest and courageous, he was one of the first who in the days of boundless revolutionary dreams and raptures uttered warnings against the dangers lurking on all sides, and even had the temerity to declare aloud that it would be better to settle on a constitutional monarchy, without being carried away by the idea of a republic which Russia as yet was incapable of realising.

These words, as well as his persistent and constant reminder that Russia would become free and powerful if only she, together with her Allies, succeeded in completely defeating Germany, gave Milyukov’s enemies the opportunity of raising a campaign against him from the very outset. He also added strength to the enemy’s position by emphasising in his statement of war aims that the possession of the Dardanelles was Russia’s vital need. This gave the Revolutionary Democracy occasion to clamour about Milyukov’s predatory aspirations and imperialism. During the Revolution all those to the right of him rather supported him. Those to the left feared or even hated him.

(2) Pavel Milyukov, Foreign Minister of the Provisional Government, letter sent to all Allied ambassadors (18th April, 1917)

Free Russia does not aim at the domination of other nations, or at occupying by force foreign territories. Its aim is not to subjugate or humiliate anyone. In referring to the "penalties and guarantees" essential to a durable peace the Provisional Government had in view reduction of armaments, the establishment of international tribunals, etc.

(3) Robert V. Daniels, Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967)

On the 20th April, Milyukov's note was made public, to the accompaniment of intense popular indignation. One of the Petrograd regiments, stirred up by the speeches of a mathematician who happened to be serving in the ranks, marched to the Marinsky Palace (the seat of the government at the time) to demand Milyukov's resignation.