On this day on 3rd April

On this day in 1876 Mary Fildes of 74 Hamilton Street, Rochdale Road, Manchester, died. She was buried on 6 April 1876 at St Luke's Church, Cheetham, Lancashire. Mary had effects valued at "under £100". In the Index of Wills in the National Probate Calendar, her grandson, Samuel Luke Fildes was named as her "sole Executor ". When Mary Fildes died her age was registered as "87" which indicates a birth year of 1789.

Mary Pritchard, the daughter of John Pritchard of Stockport, bookkeeper, and his wife, Ann Price Prichard, was born in about 1792. As her biographer Robert Poole pointed out: "Her birthplace was later given as Cork, although there are no known family connections to explain this. Her age in 1819 was given as twenty-seven, indicating a birth date of about 1792, though later statements of her age suggest a birth date of 1789." At the age of 19 Mary married William Fildes (1789-1840), a reedmaker in Stockport, Lancashire, on 17th March, 1808. A reedmaker made weaving reeds - a reed is a comb-like device for 'beating' the weft thread into place as it is passed by the shuttle.

William and Mary lived in the Manchester cotton quarter of Ancoats. They had eight children James (1808), Samuel (1809), George (1810), Robert (1815), Sarah (1816), Thomas (1818), Henry (1819) and John (1821). Being a passionate radical she named her last three sons after Thomas Paine, Henry Hunt and John Cartwright.

In June 1819 the first Female Union was formed by Alice Kitchen in Blackburn. The next one was in Stockport. "We who form and constitute the Stockport Female Union Society, having reviewed for a considerable time past the apathy, and frequent insult of our oppressed countrymen, by those sordid and all-devouring fiends, the Borough-mongering Aristocracy, and in order to accelerate the emancipation of this suffering nation, we, do declare, that we will assist the Male Union formed in this town, with all the might and energy that we possess, and that we will adhere to the principles, etc., of the Male Union…and assist our Male friends to obtain legally, the long-lost Rights and Liberties of our country."

On 20 July 1819, Mary Fildes established the Society of Female Reformers. She became president and in the first week after its formation over 1000 members joined. The organisation's flag had the figure of Justice on it. The Society of Female Reformers met in the Union Rooms, Manchester every Tuesday evening from six to nine o'clock. It had its own flag "which showed a woman holding the scales of justice and treading the serpent of corruption underfoot."

Ruth Mather has pointed out: "Female Reform Societies emerged in north-west England in the summer of 1819... and were immediately faced with the scorn and revulsion of the conservative press and caricaturists. Female Reformers were described as devoid of morals or religion, and depicted as revolutionary harridans or sexual objects, not to be taken seriously as political actors."

Susanna Saxton, was the secretary of the Manchester Female Reformers and wrote several pamphlets on the need for parliamentary reform. The most popular was The Manchester Female Reformers Address to the Wives, Mothers, Sisters and Daughters of the Higher and Middling Classes of Society which was published on 20 July, 1819. It was later published in the Manchester Observer. Saxon argued that women's main role was to support their husbands in their struggle for universal male suffrage. They were also urged "to install into the minds of our children, a deep and rooted hatred of our corrupt and tyrannical rulers."

However, as Sarah Irving has pointed out: "In these addresses the women, whilst expressing solidarity with men and asserting their right to comment publicly on political questions, made no claim for political rights for themselves, at least publicly. Their private thoughts are more difficult to discern as, unlike the men, none of the women later published political memoirs."

In March 1819, Joseph Johnson, John Knight and James Wroe formed the Manchester Patriotic Union Society. All the leading radicals in Manchester joined the organisation. Johnson was appointed secretary and Wroe became treasurer. The main objective of this new organisation was to obtain parliamentary reform and during the summer of 1819 it was decided to invite Mary Fildes, Major John Cartwright, Henry Orator Hunt and Richard Carlile to speak at a public meeting in Manchester. The men were told that this was to be "a meeting of the county of Lancashire, than of Manchester alone. I think by good management the largest assembly may be procured that was ever seen in this country." Cartwright was unable to attend but Hunt and Carlile agreed and the meeting was arranged to take place at St. Peter's Field on 16th August.

The local magistrates were concerned that such a substantial gathering of reformers might end in a riot. The magistrates therefore decided to arrange for a large number of soldiers to be in Manchester on the day of the meeting. This included four squadrons of cavalry of the 15th Hussars (600 men), several hundred infantrymen, the Cheshire Yeomanry Cavalry (400 men), a detachment of the Royal Horse Artillery and two six-pounder guns and the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry (120 men) and all Manchester's special constables (400 men).

At about 11.00 a.m. on 16th August, 1819 William Hulton, the chairman, and nine other magistrates met at Mr. Buxton's house in Mount Street that overlooked St. Peter's Field. Although there was no trouble the magistrates became concerned by the growing size of the crowd. Estimations concerning the size of the crowd vary but Hulton came to the conclusion that there were at least 50,000 people in St. Peter's Field by midday. Hulton therefore took the decision to send Edward Clayton, the Boroughreeve and the special constables to clear a path through the crowd. The 400 special constables were therefore ordered to form two continuous lines between the hustings where the speeches were to take place, and Mr. Buxton's house where the magistrates were staying.

The main speakers at the meeting arrived at 1.20 p.m. Mary Fildes arrived with Henry 'Orator' Hunt. She sat next to the coachman, waving a handkerchief embroidered as a flag. Two other female activists, Elizabeth Gaunt and Sarah Hargreaves remained in the carriage while Fildes and Hunt climbed onto the constructed platform. The plan was for her to read out an address "as wives, mothers, daughters" declaring their support for a radical reform of parliament, ending: "may our flag never be unfurled but in the cause of peace and reform, and then may a female's curse pursue the coward who deserts the standard".

It was arranged that Mary Fildes was to present male leaders with the symbolic "cap of liberty", an emblem with Saxon as well as French connotations. Fildes also gave Hunt the "colours" of the Manchester Female Reform Society. It has been pointed out that William Cobbett patronisingly equated this action with the role of queens at jousts in blessing the participants.

At 1.30 p.m. the magistrates came to the conclusion that "the town was in great danger". Hulton therefore decided to instruct Joseph Nadin, Deputy Constable of Manchester, to arrest the other leaders of the demonstration who were now assembled on the platform. Nadin replied that this could not be done without the help of the military. Lieutenant Colonel George L'Estrange, the commander of the military forces in Manchester and Major Thomas Trafford, the commander of the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry, chose Captain Hugh Birley to carry out the order. Local eyewitnesses claimed that most of the sixty men who Birley led into St. Peter's Field were drunk. Birley later insisted that the troop's erratic behaviour was caused by the horses being afraid of the crowd. Robert Poole has argued that the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry had "vowed to capture the Manchester colours after humiliating failures at meetings elsewhere."

When Captain Hugh Birley and his men reached the hustings they attempted to arrest Mary Fildes, Henry Hunt, John Knight, Joseph Johnson, George Swift, John Saxton, John Tyas, John Moorhouse and Robert Wild. As well as the speakers and the organisers of the meeting, Birley also arrested the newspaper reporters on the hustings. John Edward Taylor reported: "A comparatively undisciplined body, led on by officers who had never had any experience in military affairs, and probably all under the influence both of personal fear and considerable political feeling of hostility, could not be expected to act either with coolness or discrimination; and accordingly, men, women, and children, constables, and Reformers, were equally exposed to their attacks."

Some reports claimed that the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry attempted to murder Mary Fildes while arresting the leaders of the demonstration. According to the record of those injured, Fildes was "much beat by Constables & leaped off the Hustings when Mr Hunt was taken, and was obliged to absent herself a fortnight to avoid imprisonment".

One eyewitness described how "Mrs. Fildes, hanging suspended by a nail which had caught her white dress, was slashed across her exposed body by one of the brave cavalry." According to Mary Fildes's own petition to the House of Commons, she was beaten to the ground by a truncheon-wielding special constable who then wrenched the embroidered handkerchief from her. Shortly afterwards she was saved from another sabre cut by the upraised truncheon of a special constable who recognized her and "in making her way through the crowd, heard with horror the shrieks and cries of the dying and the wounded".

Other female reformers including Elizabeth Gaunt, Sarah Hargreaves, and Mary Waterworth were arrested, possibly in mistake for Fildes. When her handkerchief-flag was displayed that evening as a trophy in the window of a local shop, it provoked riots which led to further casualties. The heavily pregnant woman, Elizabeth Gaunt was badly beaten and later thrown into the New Bailey Prison, where she was kept in solitary confinement and physically abused.

Mary Fildes survived but at least 18 people were killed, of whom four were women. These were named as: Margaret Downes (sabred), Mary Heys (trampled by cavalry), Sarah Jones (truncheoned) and Martha Partington (crushed in a cellar). (16) Around a quarter of those injured were female; as women formed fewer than one in eight of those present, it seems that they were deliberately targeted. Two miscarriages and one premature birth were attributed to injuries on the field. (16a) Fildes, who was living at 3 Comet Street, went into hiding for a fortnight to avoid imprisonment. Eventually she was awarded 40/- (£2) by the Peterloo Relief Fund.

Mary Fildes remained an active reformer. Her name featured prominently on an address from the Manchester female reformers to William Cobbett in late 1819 and on an address to the king's estranged wife Queen Caroline in 1820 which proclaimed: "As the chiefs of a cruel and corrupt system have levelled their menaces at you, so have the drawn sabres and the fixed bayonets of their armed satellites been brandished at us".

In 1823 she received a package of leaflets giving explicit practical advice on birth control, with a request to pass them on to other married women. The anonymous sender was Francis Place and he suggested that they had originally come from Robert Carlile. According to Henry Hetherington she was arrested and charged with the distribution of pornography.

Mary Fildes was also active in the Chartist movement. In 1833 Mary Fildes visited Heywood to launch a branch of the Female Political Union of the Working Classes. In 1843 two lectures which she gave on ‘War' in Chorlton-upon-Medlock were advertised in the Northern Star. Her sons James and John Cartwright Fildes were active Chartists in Salford.

After the death of her husband she moved to Chester where she became the landlady of the Shrewsbury Arms in Frodsham Street. In 1849 she inherited four small properties in Frodsham Street, Chester, from her aunt, Mary Price; she moved there to live in one of them with her mother, Ann."

In the 1851 Mary Fildes was living with her mother Ann Brown (aged 89), and her grand-daughter Emma Fildes (aged 11), the daughter of George Fildes. In the Census returns Mary gives her place of birth as Manchester, Lancashire.

At this time her son James, a former seaman, was living in Liverpool with his Irish Catholic wife and five children, moving house repeatedly. Three other children had died in infancy, and in 1854 Mary took her eleven-year-old grandson Samuel Luke Fildes from them to live with her in Chester. His mother later wrote, "you fancied that I did not care for you but Samuel that was a mistaken notion." His son L. V. Fildes, claimed that his father was never told why he was "adopted" by his grandmother.

According to David Croal Thomson his father had died and his mother had remarried. In 1857 he began attending evening classes in art at Chester's Mechanics' Institute. Although Mary Fildes initially disapproved of her grandson studying art, she supported him financially during his studies.

On this day in 1881 members of the People's Will responsible for the assassination of Tsar Alexander II are executed. In October, 1879, the Land and Liberty group split into two factions. The majority of members, who favoured a policy of terrorism, established the People's Will (Narodnaya Volya). Others, such as George Plekhanov formed Black Repartition, a group that rejected terrorism and supported a socialist propaganda campaign among workers and peasants. Elizabeth Kovalskaia was one of those who rejected the ideas of the People's Will: "Firmly convinced that only the people themselves could carry out a socialist revolution and that terror directed at the centre of the state (such as the People's Will advocated) would bring - at best - only a wishy-washy constitution which would in turn strengthen the Russian bourgeoisie, I joined Black Repartition, which had retained the old Land and Liberty program."

Vera Figner, Anna Korba, Andrei Zhelyabov, Olga Liubatovich, Nikolai Morozov, Timofei Mikhailov, Lev Tikhomirov, Mikhail Frolenko, Grigory Isaev, Sophia Perovskaya, Nikolai Sablin, Ignatei Grinevitski, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov, Gesia Gelfman, Anna Yakimova, Sergei Kravchinskii, Tatiana Lebedeva and Alexander Kviatkovsky all joined the People's Will. Figner later recalled: "We divided up the printing plant and the funds - which were in fact mostly in the form of mere promises and hopes... And as our primary aim was to substitute the will of the people for the will of one individual, we chose the name Narodnaya Volya for the new Party."

Michael Burleigh, the author of Blood & Rage: A Cultural History of Terrorism (2008), has argued that the main influence on this small group was Sergi Nechayev: "The terrorist nucleus of Land and Freedom had already adopted many of Nechayev's dubious practices, including bank robberies and murdering informers. People's Will also borrowed his tactic of suggesting to the credulous that it was the tip of a much larger revolutionary organisation - the Russian Social Revolutionary Party - which in reality was non-existent. There was an imposing-sounding Executive Committee all right, but this was coterminous with the entire membership of People's Will... In fact, People's Will never had more than thirty or forty members, who would then recruit agents for spectific tasks or to establish affiliate cells within sections of society deemed to have revolutionary potential."

Soon afterwards the People's Will decided to assassinate Alexander II. According to the historian, Joel Carmichael: "Although this populist organization retained the same humane vocabulary - revolving around socialism, faith in the people, the overthrow of the autocracy, and democratic representation - its sole objective was, in fact, the murder of the tsar. The preparation for this demanded boundless zeal, painstaking diligence, and great personal daring. In fact, the idealism of these young assassins was perhaps the most impressive thing about the whole populist movement. Though a few populist leaders were of peasant origin, most were drawn from the intelligentsia of the upper and middle classes. The motives of the latter were quite impersonal ; one of the things that baffled the police in stamping out the movement - in which they never succeeded - was just this combination of zeal and selflessness. The actual membership of the populist societies was relatively small. But their ideas attracted wide support, even in the topmost circles of the bureaucracy and, for that matter, in the security police as well. The upper-class origins of many of the revolutionaries meant a source of funds; many idealists donated their entire fortunes to the movement."

A directive committee was formed consisting of Andrei Zhelyabov, Timofei Mikhailov, Lev Tikhomirov, Mikhail Frolenko, Vera Figner, Sophia Perovskaya and Anna Yakimova. Zhelyabov was considered the leader of the group. However, Figner considered him to be overbearing and lacking in depth: "He had not suffered enough. For him all was hope and light." Zhelyabov had a magnetic personality and had a reputation for exerting a strong influence over women.

Zhelyabov and Perovskaya attempted to use nitroglycerine to destroy the Tsar train. However, the terrorist miscalculated and it destroyed another train instead. An attempt the blow up the Kamenny Bridge in St. Petersburg as the Tsar was passing over it was also unsuccessful. Figner blamed Zhelyabov for these failures but others in the group felt he had been unlucky rather than incompetent.

In November 1879 Stefan Khalturin managed to find work as a carpenter in the Winter Palace. According to Adam Bruno Ulam, the author of Prophets and Conspirators in Pre-Revolutionary Russia (1998): "There was, incomprehensible as it seems, no security check of workman employed at the palace. Stephan Khalturin, a joiner, long sought by the police as one of the organizers of the Northern Union of Russian workers, found no difficulty in applying for and getting a job there under a false name. Conditions at the palace, judging from his reports to revolutionary friends, epitomized those of Russia itself: the outward splendor of the emperor's residence concealed utter chaos in its management: people wandered in and out, and imperial servants resplendent in livery were paid as little as fifteen rubles a month and were compelled to resort to pilfering. The working crew were allowed to sleep in a cellar apartment directly under the dining suite."

Khalturin approached George Plekhanov about the possibility of using this opportunity to kill Tsar Alexander II. He rejected the idea but did put him in touch with the People's Will who were committed to a policy of assassination. It was agreed that Khalturin should try and kill the Tsar and each day he brought packets of dynamite, supplied by Anna Yakimova and Nikolai Kibalchich, into his room and concealed it in his bedding. Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976), has argued: "His workmates regarded him as a clown and a simpleton and warned him against socialists, easily identifiable apparently for their wild eyes and provocative gestures. He worked patiently, familiarizing himself with the Tsar's every movement, and by mid-January Yakimova and Kibalchich had provided him with a hundred pounds of dynamite, which he hid under his bed."

On 17th February, 1880, Stefan Khalturin constructed a mine in the basement of the building under the dinning-room. The mine went off at half-past six at the time that the People's Will had calculated Alexander II would be having his dinner. However, his main guest, Prince Alexander of Battenburg, had arrived late and dinner was delayed and the dinning-room was empty. Alexander was unharmed but sixty-seven people were killed or badly wounded by the explosion.

This disaster resulted in a heated debate on the purposes of terrorism. One faction that included Nikolai Morozov and Olga Liubatovich, argued that the main objective was to force the government to grant democratic rights to the people of Russia. However, another faction, led by Lev Tikhomirov, believed that it was possible for a small group of revolutionaries to use terrorism in order to directly capture power. Liubatovich argued: "During the debates, the question of Jacobinism - seizing power and ruling from above, by decree - was raised. As I saw it, the Jacobin tinge that Tikhomirov gave to his program for the Executive Committee gave to his program for the Executive Committee threatened the party and the entire revolutionary movement with moral death; it was a kind of rebirth of Nechaevism, which had long since lost moral credit in the revolutionary world. It was my belief that the revolutionary idea could be a life-giving force only when it was the antithesis of all coercion - social, state, and even personal coercion, tsarist and Jacobin alike. Of course, it was possible for a narrow group of ambitious men to replace one form of coercion or authority by another. But neither the people nor educated society would follow them consciously, and only a conscious movement can impart new principles to public life." Liubatovich and Morozov left the organization and Tikomirov's views prevailed.

The People's Will contacted the Russian government and claimed they would call off the terror campaign if the Russian people were granted a constitution that provided free elections and an end to censorship. On 25th February, 1880, Alexander II announced that he was considering granting the Russian people a constitution. To show his good will a number of political prisoners were released from prison. Mikhail Loris-Melikof, the Minister of the Interior, was given the task of devising a constitution that would satisfy the reformers but at the same time preserve the powers of the autocracy. At the same time the Russian Police Department established a special section that dealt with internal security. This unit eventually became known as the Okhrana. Under the control of Loris-Melikof, undercover agents began joining political organizations that were campaigning for social reform.

In January, 1881, Mikhail Loris-Melikof presented his plans to Alexander II. They included an expansion of the powers of the Zemstvo. Under his plan, each zemstov would also have the power to send delegates to a national assembly called the Gosudarstvenny Soviet that would have the power to initiate legislation. Alexander was concerned that the plan would give too much power to the national assembly and appointed a committee to look at the scheme in more detail.

The People's Will became increasingly angry at the failure of the Russian government to announce details of the new constitution. They therefore began to make plans for another assassination attempt. Those involved in the plot included Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Vera Figner, Anna Yakimova, Grigory Isaev, Gesia Gelfman, Nikolai Sablin, Ignatei Grinevitski, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov, Mikhail Frolenko, Timofei Mikhailov, Tatiana Lebedeva and Alexander Kviatkovsky.

Kibalchich, Isaev and Yakimova were commissioned to prepare the bombs that were needed to kill the Tsar. Isaev made some technical error and a bomb went off badly damaging his right hand. Yakimova took him to hospital, where she watched over his bed to prevent him from incriminating himself in his delirium. As soon as he regained consciousness he insisted on leaving, although he was now missing three fingers of his right hand. He was unable to continue working and Yakimova now had sole responsibility for preparing the bombs.

A crisis meeting was held in which Timofei Mikhailov called for work to continue on all fronts. However, Sophia Perovskaya and Anna Yakimova argued that they should concentrate on the plans to assassinate the Tsar. Nikolai Kibalchich was heard to remark: "Have you noticed how much crueller our girls are than our men?" It was eventually agreed that Perovkaya and Yakimova were right. It was decided to form a watching party. These members had the task of noting every movement of the Tsar.

It was discovered that every Sunday the Tsar took a drive along Malaya Sadovaya Street. It was decided that this was a suitable place to attack. Yakimova was given the task of renting a flat in the street. Gesia Gelfman had a flat on Telezhnaya Street and this became the headquarters of the assassins whereas the home of Vera Figner was used as an explosives workshop.

Nikolai Kibalchich wanted to make a nitroglycerine bomb but Andrei Zhelyabov regarded it as "unreliable". Sophia Perovskaya favoured mining. Eventually it was decided that the Tsar's carriage should be mined, with hand grenades at the ready as a second strategy. If all else failed, one of the members of the assassination team should step forward and stab the Tsar with a dagger. It was Kibalchich's job to provide the hand grenades.

The Okhrana discovered that their was a plot to kill Alexander II. One of their leaders, Andrei Zhelyabov, was arrested on 28th February, 1881, but refused to provide any information on the conspiracy. He confidently told the police that nothing they could do would save the life of the Tsar. Alexander Kviatkovsky, another member of the assassination team, was arrested soon afterwards.

The conspirators decided to make their attack on 1st March, 1881. Sophia Perovskaya was worried that the Tsar would now change his route for his Sunday drive. She therefore gave the orders for bombers to he placed along the Ekaterinsky Canal. Grigory Isaev had laid a mine on Malaya Sadovaya Street and Anna Yakimova was to watch from the window of her flat and when she saw the carriage approaching give the signal to Mikhail Frolenko.

Tsar Alexander II decided to travel along the Ekaterinsky Canal. An armed Cossack sat with the coach-driver and another six Cossacks followed on horseback. Behind them came a group of police officers in sledges. Perovskaya, who was stationed at the intersection between the two routes, gave the signal to Nikolai Rysakov and Timofei Mikhailov to throw their bombs at the Tsar's carriage. The bombs missed the carriage and instead landed amongst the Cossacks. The Tsar was unhurt but insisted on getting out of the carriage to check the condition of the injured men. While he was standing with the wounded Cossacks another terrorist, Ignatei Grinevitski, threw his bomb. Alexander was killed instantly and the explosion was so great that Grinevitski also died from the bomb blast.

The terrorists quickly escaped from the scene and that evening assembled at the flat being rented by Vera Figner. She later recalled: "Everything was peaceful as I walked through the streets. But half an hour after I reached the apartment of some friends, a man appeared with the news that two crashes like cannon shots had rung out, that people were saying the sovereign had been killed, and that the oath was already being administered to the heir. I rushed outside. The streets were in turmoil: people were talking about the sovereign, about wounds, death, blood.... I rushed back to my companions. I was so overwrought that I could barely summon the strength to stammer out that the Tsar had been killed. I was sobbing; the nightmare that had weighed over Russia for so many years had been lifted. This moment was the recompense for all the brutalities and atrocities inflicted on hundreds and thousands of our people.... The dawn of the New Russia was at hand! At that solemn moment all we could think of was the happy future of our country."

The evening after the assassination the Executive Committee of the People's Will sent an open letter announcing it was willing to negotiate with the authorities: "The inevitable alternatives are revolution or a voluntary transfer of power to the people. We turn to you as a citizen and a man of honour, and we demand: (i) amnesty for all political prisoners, (ii) the summoning of a representative assembly of the whole nation". Karl Marx was one of many radicals who sent a message of support after the publication of the letter.

Nikolai Rysakov, one of the bombers was arrested at the scene of the crime. Sophia Perovskaya told her comrades: "I know Rysakov and he will say nothing." However, Rysakov was tortured by the Okhrana and was forced to give information on the other conspirators. The following day the police raided the flat being used by the terrorists. Gesia Gelfman was arrested but Nikolai Sablin committed suicide before he could be taken alive. Soon afterwards, Timofei Mikhailov, walked into the trap and was arrested.

Thousands of Cossacks were sent into St. Petersburg and roadblocks were set up, and all routes out of the city were barred. An arrest warrant was issued for Sophia Perovskaya. Her bodyguard, Tyrkov, claimed that she seemed to have "lost her mind" and refused to try and escape from the city. According to Tyrkov, her main concern was to develop a plan to rescue Andrei Zhelyabov from prison. She became depressed when on the 3rd March, the newspapers reported that Zhelyabov had claimed full responsibility for the assassination and therefore signing his own death warrant.

Perovskaya was arrested while walking along the Nevsky Prospect on 10th March. Later that month Nikolai Kibalchich, Grigory Isaev and Mikhail Frolenko were also arrested. However, other members of the conspiracy, including Vera Figner and Anna Yakimova, managed to escape from the city. Perovskaya was interrogated by Vyacheslav Plehve, the Director of the Police Department. She admitted her involvement in the assassination but refused to name any of her fellow conspirators.

V. N. Gerard later recalled "When his men came to see Kibalchich as his appointed counsel for the defense I was surprised above all by the fact that his mind was occupied with completely different things with no bearing on the present trial. He seems to be immersed in research on some aeronautic missile; he thirsted for a possibility to write down his mathematical calculations involved in the discovery. He wrote them down and submitted them to the authorities." According to Lee B. Croft, the author of Nikolai Ivanovich Kibalchich: Terrorist Rocket Pioneer (2006) in a note written in his prison cell, Kybalchych proposed a manned jet air-navigating apparatus. He examined the design of powder rocket engine, controlling the flight by changing engines angle.

The trial of Zhelyabov, Perovskaya, Kibalchich, Rysakov, Gelfman and Mikhailov, opened on 25th March, 1881. Prosecutor Muraviev read his immensely long speech that included the passage: "Cast out by men, accursed of their country, may they answer for their crimes before Almighty God! But peace and calm will be restored. Russia, humbling herself before the Will of that Providence which has led her through so sore a burning faith in her glorious future."

Prosecutor Muraviev concentrated his attack on Sophia Perovskaya: "We can imagine a political conspiracy; we can imagine that this conspiracy uses the most cruel, amazing means; we can imagine that a woman should be part of this conspiracy. But that a woman should lead a conspiracy, that she should take on herself all the details of the murder, that she should with cynical coldness place the bomb-throwers, draw a plan and show them where to stand; that a woman should have become the life and soul of this conspiracy, should stand a few steps away from the place of the crime and admire the work of her own hands - any normal feelings of morality can have no understanding of such a role for women." Perovskaya replied: "I do not deny the charges, but I and my friends are accused of brutality, immorality and contempt for public opinion. I wish to say that anyone who knows our lives and the circumstances in which we have had to work would not accuse us of either immorality or brutality."

Karl Marx followed the trial with great interest. He wrote to his daughter, Jenny Longuet: "Have you been following the trial of the assassins in St. Petersburg? They are sterling people through and through.... simple, businesslike, heroic. Shouting and doing are irreconcilable opposites... they try to teach Europe that their modus operandi is a specifically Russian and historically inevitable method about which there is no more reason to moralize - for or against - then there is about the earthquake in Chios."

Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov, Gesia Gelfman and Timofei Mikhailov were all sentenced to death. Gelfman announced she was four months pregnant and it was decided to postpone her execution. Perovskaya, as a member of the high nobility, she could appeal against her sentence, however, she refused to do this. It was claimed that Rysakov had gone insane during interrogation. Kibalchich also showed signs that he was mentally unbalanced and talked constantly about a flying machine he had invented.

On 3rd April 1881, Zhelyabov, Perovskaya, Kibalchich, Rysakov and Mikhailov were given tea and handed their black execution clothes. A placard was hung round their necks with the word "Tsaricide" on it. Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976), has pointed out: "Then the party set off. It was headed by the police carriage, followed by Zhelyabov and Rysakov. Sophia sat with Kibalchich and Mikhailov in the third tumbril. A pale wintry sun shone as the party moved slowly through the streets, already crowded with onlookers, most of them waving and shouting encouragement. High government officials and those wealthy enough to afford the tickets were sitting near to the scaffold that had been erected on Semenovsky Square. The irreplaceable Frolov, Russia's one and only executioner, fiddled drunkenly with the nooses, and Sophia and Zhelyabov were able to say a few last words to one another. The square was surrounded by twelve thousand troops and muffled drum beats sounded. Sophia and Zhelyabov kissed for the last time, then Mikhailov and Kibalchich kissed Sophia. Kibalchich was led to the gallows and hanged. Then it was Mikhailov's turn. Frolov was by now barely able to see straight and the rope broke three times under Mikhailov's weight." It was now Perovskaya's turn. "It's too tight" she told him as he struggled to tie the noose. She died straight away but Zhelyabov, whose noose had not been tight enough, died in agony.

Gesia Gelfman remained in prison. According to her friend, Olga Liubatovich: "Gesia languished under the threat of execution for five months; finally her sentence was commuted, just before she was to deliver. At the hands of the authorities, the terrible act of childbirth became a case of torture unprecedented in human history. For the delivery, they transferred her to the House of Detention. The torments suffered by poor Gesia Gelfman exceeded those dreamed up by the executioners of the Middle Ages; but Gesia didn't go mad - her constitution was too strong. The child was born live, and she was even able to nurse it." Soon after she gave birth her daughter was taken from her. Gelfman died five days later on 12th October, 1882.

Anna Yakimova, who was also pregnant, probably by Grigory Isaev, managed to escape to Kiev. She was soon arrested and she was tried alongside Isaev, Mikhail Frolenko, Tatiana Lebedeva and sixteen other party members. Although they were all found guilty, because of the international protests by Victor Hugo and other well-known figures, they were not sentenced to death. Instead they were sent to Trubetskov Dungeon. As Cathy Porter has pointed out: "Those sentenced in the Trial of the 20 were sent to the Trubetskov Dungeon, one of the most horrible of Russian prisons. Few survived the ordeal; torture and rape were everyday occurrences in the dungeons, through whose soundproofed walls little information reached the outside world.... After a year in Trubetskoy, during which most of the prisoners had died or committed suicide."

and Timofei Mikhailov being executed on 3rd April, 1881.

On this day in 1886 Barbara Ayrton Gould, the daughter of William Ayrton and Hertha Ayrton. Her half-sister was Edith Zangwill. She was educated at Notting Hill High School and University College, where she studied chemistry and physiology.

In 1906 Barbara Ayrton joined the Women Social & Political Union. In 1908 she gave up her post-graduate research in order to work full-time as an organizer for the WSPU. In November 1909 she played the part of Grace Darling in A Pageant of Great Women at the Scala Theatre, a play by Cicely Hamilton.

In July 1910, Barbara Ayrton, married Gerald Gould. A fellow socialist, Gould was a Fellow of Merton College at the University of Oxford. He was also a supporter of women's suffrage and had joined forces with Henry Nevinson, Laurence Housman, Charles Corbett, Henry Brailsford, C. E. M. Joad, Israel Zangwill, Hugh Franklin and Charles Mansell-Moullin to establish the Men's League For Women's Suffrage.

On 4th March, 1912 the WSPU organised another window-breaking demonstration. This time the target was government offices in Whitehall. According to Votes for Women: "From in front, behind, from every side it came - a hammering, crashing, splintering sound unheard in the annals of shopping... At the windows excited crowds collected, shouting, gesticulating. At the centre of each crowd stood a woman, pale, calm and silent." Over 200 suffragettes were arrested and jailed for taking part in the demonstration. This included Barbara Gould was arrested for breaking windows in Regent Street. She was remanded in Holloway Prison but was released without charge.

In October 1912, Christabel Pankhurst told Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When Emmeline and Frederick objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

Barbara Ayrton Gould also disagreed with the arson campaign and left the WSPU. On 6th February, 1914, she became one of the founding members of the United Suffragists. Other members included Gerald Gould, Evelyn Sharp, Lena Ashwell, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, John Scurr, George Lansbury, Gerald Gould, Hertha Ayrton, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Edith Zangwill, Israel Zangwill, Laurence Housman and Henry Nevinson. She was also a member of the Tax Resistance League.

In 1921 Barbara gave birth to Michael Ayrton. She was honorary secretary of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. She also remained active in the Labour Party and was a member of the national executive for over 20 years. She was also vice-chairman from 1938 to 1939 and chairman from 1939 to 1940. At the fifth attempt, she was elected to represent North Hendon in the 1945 General Election.

Barbara Ayrton Gould died on 14th October 1950.

On this day in 1894 Dora Black, the daughter of Frederick Black, a senior Civil servant, was born in London. Black held strong progressive views and believed that girls had the right to as good an education as boys. Dora responded well to her father's encouragement and won scholarships to Sutton High School and Girton College, Cambridge. At university she gained a first-class honours degree in modern languages.

Dora met Bertrand Russell in 1916 and soon afterwards he asked her to marry him. Dora's feminism involved a belief in sexual freedom and although she was willing to live with Bertrand, she rejected his proposal of marriage. Dora saw marriage as a restriction on women's liberty, and although Bertrand accepted her philosophical argument on the subject, he wanted a son and legitimate heir to the family title.

In the First World War Dora joined Russell's campaign against military conscription. After Russell was released from Brixton Prison in 1918 for his role in the struggle against the Military Service Act. Dora and Bertrand visited Russia and China together.

When they returned to England in 1921 Dora agreed to marry Bertrand Russell. After giving birth to her first child Dora became involved in the birth control movement. The 1923 Dora Russell along with Maynard Keynes, paid for the legal costs to obtain the freedom of Guy Aldred and Rose Witcop after they had been found guilty of selling pamphlets on contraception. The following year, Dora, with the support of Katharine Glasier, Susan Lawrence, Margaret Bonfield, Dorothy Jewson and H. G. Wells founded the Workers' Birth Control Group. Dora also campaigned within the Labour Party for birth-control clinics but this was rejected as they feared losing the Roman Catholic vote.

Dora Russell did a considerable amount of writing during this period. With Bertrand she wrote The Prospects of Industrial Civilization (1923) and two years later she published her book, Hypatia: Women and Knowledge. The book was severely attacked by people who disapproved of Dora's theories on sexual freedom for women.

In 1927 Dora and Bertrand Russell opened their own progressive boarding school, Beacon Hill, near Harting, West Sussex. The school reflected Bertrand's view that children should not be forced to follow a strictly academic curriculum. Other aspects of the school illustrated Dora's ideas on education. The school was run on the principle that freedom, if understood early enough, would result in maturity and self-discipline. Dora also emphasized co-operation rather than competition and believed that the best way to teach the benefits of democracy was to run the school on democratic lines. Dora's educational philosophy was expressed in her book In Defence of Children (1932).

Both Bertrand and Dora continued to have sexual relationships with other partners. This resulted in Dora having two children with the journalist, Griffin Barry. In 1935 Bertrand Russell left Dora for one of his students, Patricia Spence. When Barry returned to the United States, Dora continued to run Beacon Hill School on her own until the Second World War when she went to work for the Ministry of Information.

Dora was active in the peace movement after the war and in 1958 joined with Bertrand Russell, J. B. Priestley, Vera Brittain, Fenner Brockway, Victor Gollancz, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot to form the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). Later that year Dora organised the Women's Caravan of Peace and toured with it through much of Europe.

After retiring to Cornwall in 1962, Dora wrote Religion and the Machine Age (1982) and three volumes of autobiography, The Tamarisk Tree (1977, 1981, 1985).

Dora Russell died on 31st May, 1986.

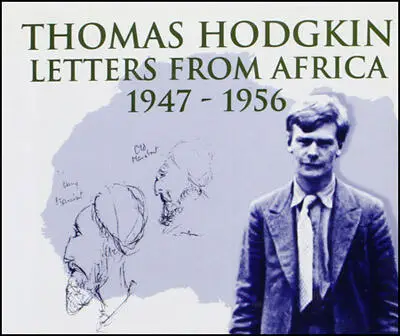

On this day in 1910 Thomas Lional Hodgkin was born. He was educated at Dragon School, Winchester College and Oxford University. After obtaining a first class degree he taught at Manchester University.

In 1934 Hodgkin joined the Colonial Office. His first post was in Palestine. This experience made him highly critical of Britain's foreign policy. He wrote: "Truly, all imperialism is fundamentally alike - imposed by force and maintained by the fear of force and from time to time by actual force." In May 1936 Hodgkin resigned because he found it "morally impossible to participate in government's repressive measures."

Hodgkin returned to England and became a school teacher in London. He wrote a pamphlet on Palestine for the Labour Monthly. Hodgkin also joined the Communist Party and took part in the campaign against the growth of Anti-Semitism organized by Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists. In 1937 he married fellow communist Dorothy Crowfoot, the Nobel Prize winning chemist.

In 1939 Hodgkin became organising tutor in the North Staffordshire district of the WEA. He worked under George Wigg who later recruited Hodgkin to help him provide adult education in the armed forces during the Second World War. Other friends during this period included Stephen Swingler and Harold Davies, who like Wigg, went on to be a Labour Party MPs. Hodgson also became the editor of the Association of Tutors in Adult Education newsletter.

After the war Hodgkin was involved in setting up adult education classes in Africa. He was also a member of the Union of Democratic Control (UDC) that at that time was led by Kingsley Martin, the editor of the New Statesman.

Now recognized as one of the world's leading experts on colonialism he taught at a variety of different university. This included the publication of Nationalism in Colonial Africa (1957) and African Political Parties (1961). In 1962 he was appointed as head of the Institute of African Studies in Ghana. Other books by Hodgkin include Vietnam: The Revolutionary Path.

Thomas Hodgkin died on 25th March 1982.

On this day in 1913 Women Social & Political Union activist Elsie Duval is arrested for "loitering with intent". She was sentenced to one month's imprisonment. After being released under the Cat and Mouse Act, she escaped with her boyfriend, Hugh Franklin, to Belgium and stayed in Brussels. She received a letter from Jessie Kenney that said: "Miss Pankhurst thinks it would be better for you to stay where you are for the time being and until you get stronger."

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Duval and Franklin now returned to England.

During the First World War she applied to work with Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray in a hospital in Claridge Hotel in Paris. The offer was rejected and on 28th September 1915 she married Hugh Franklin in the West London Synagogue. His father disinherited him for marrying out of the Jewish faith and never saw him again.

Elsie Duval became ill during the influenza epidemic and died of heart failure on 1st January 1919. It is believed that her heart had been weakened by the treatment she received in prison.

On this day in 1913 Emmeline Pankhurst is sentenced her to three years' penal servitude for procuring and inciting persons to commit acts of violence. In January 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst made a speech where she stated that it was now clear that Herbert Asquith had no intention to introduce legislation that would give women the vote. She now declared war on the government and took full responsibility for all acts of militancy. "Over the next eighteen months, the WSPU was increasingly driven underground as it engaged in destruction of property, including setting fire to pillar boxes, raising false fire alarms, arson and bombing, attacking art treasures, large-scale window smashing campaigns, the cutting of telegraph and telephone wires, and damaging golf courses".

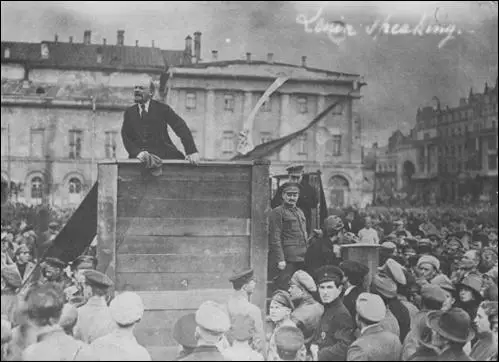

On this day in 1917 Lenin announces April Theses. When he returned to Russia, he announced what became known as the April Theses. As he left the railway station Lenin was lifted on to one of the armoured cars specially provided for the occasions. The atmosphere was electric and enthusiastic. Feodosiya Drabkina, who had been an active revolutionary for many years, was in the crowd and later remarked: "Just think, in the course of only a few days Russia had made the transition from the most brutal and cruel arbitrary rule to the freest country in the world."

In his speech Lenin attacked Bolsheviks for supporting the Provisional Government. Instead, he argued, revolutionaries should be telling the people of Russia that they should take over the control of the country. In his speech, Lenin urged the peasants to take the land from the rich landlords and the industrial workers to seize the factories. Lenin accused those Bolsheviks who were still supporting the government of Prince Georgi Lvov of betraying socialism and suggested that they should leave the party. Lenin ended his speech by telling the assembled crowd that they must "fight for the social revolution, fight to the end, till the complete victory of the proletariat".

Some of the revolutionaries in the crowd rejected Lenin's ideas. Alexander Bogdanov called out that his speech was the "delusion of a lunatic." Joseph Goldenberg, a former of the Bolshevik Central Committee, denounced the views expressed by Lenin: "Everything we have just heard is a complete repudiation of the entire Social Democratic doctrine, of the whole theory of scientific Marxism. We have just heard a clear and unequivocal declaration for anarchism. Its herald, the heir of Bakunin, is Lenin. Lenin the Marxist, Lenin the leader of our fighting Social Democratic Party, is no more. A new Lenin is born, Lenin the anarchist."

The journalist, Harold Williams rejected the idea that Lenin could play an important role in affairs: "Lenin, leader of the extreme faction of the Social Democrats, arrived here on Monday night by way of Germany. His action in accepting from the German government a passage from Switzerland through Germany arouses intense indignation here. He has come back breathing fire, and demanding the immediate and unconditional conclusions of peace, civil war against the army and government, and vengeance on Kerensky and Chkheidze, whom he describes as traitors to the cause of International Socialism. At the meeting of Social Democrats yesterday his wild rant was received in dead silence, and he was vigorously attacked, not only by the more moderate Social Democrats, but by members of his own faction. Lenin was left absolutely without supporters. The sharp repulse given to this firebrand was a healthy sign of the growth of practical sense of the Socialist wing, and the generally moderate and sensible tone of the conference of provincial workers' and soldiers' deputies was another hopeful indication of the passing of the revolutionary fever."

Albert Rhys Williams, an American visitor to Russia, disagreed with this viewpoint. Williams was convinced that the Bolsheviks would become the new rulers: "The Bolsheviks understood the people. They were strong among the more literate strata, like the sailors, and comprised largely the artisans and labourers of the cities. Sprung directly from the people's lions they spoke the people's language, shared their sorrows and thought their thoughts. They were the people. So they were trusted."

Joseph Stalin was in a difficult position. As one of the editors of Pravda, he was aware that he was being held partly responsible for what Lenin had described as "betraying socialism". Stalin had two main options open to him: he could oppose Lenin and challenge him for the leadership of the party, or he could change his mind about supporting the Provisional Government and remain loyal to Lenin. After ten days of silence, Stalin made his move. In the newspaper he wrote an article dismissing the idea of working with the Provisional Government. He condemned Alexander Kerensky and Victor Chernov as counter-revolutionaries, and urged the peasants to takeover the land for themselves.

Leon Trotsky supported Lenin's view and urged the overthrow of the Provisional Government. On the evening of 24th October, orders were given for the Bolsheviks to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The Smolny Institute became the headquarters of the revolution and was transformed into a fortress. Trotsky reported that the "chief of the machine-gun company came to tell me that his men were all on the side of the Bolsheviks".

in Petrograd in 1917. By the steps, awaiting his turn to speak, is Leon Trotsky.

On this day in 1940 Neville Chamberlain appointed Lord Beaverbrook as minister of aircraft production. Beaverbrook was a strong supporter of appeasement in the late 1930s and his newspaper praised Chamerlain and the Munich Agreement, with the Daily Express claiming on 22nd September 1938 that Britain had made no pledge to protect the frontiers of Czechoslovakia. In March 1939 he denied that Chamberlain had made any absolute guarantee to Poland, and when war broke out in September, Beaverbrook's political judgement was severely damaged.

After a meeting with Winston Churchill on 10th May, 1940, Beaverbrook threw his energy behind the war effort. Churchill let Beaverbrook remain as minister of aircraft production, knowing how good Beaverbrook was at inspiring and driving staff. Beaverbrook took over responsibility for repairs to damaged aircraft, as well as production of new planes. On 2nd August he became a member of the war cabinet.

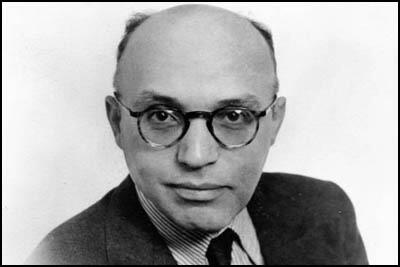

On this day in 1950 composer Kurt Weill dies. Kurt Weill was born in Dessau, Germany, on 2nd March, 1900. He studied music under Engelbert Humperdinck and Ferruccio Busoni and his early works included two symphonies.

In 1927 Weill collaborated with the writer, Bertolt Brecht to produce the musical play, Mahagonny. They then produced The Threepenny Opera (1928). Although based on The Beggar's Opera that was originally produced in 1728, Brecht added his own lyrics that illustrated his growing belief in Marxism. Weill also worked with Brecht on Happy End (1929).

Weill was a socialist and when Hitler gained power in 1933 he was forced to flee from Germany. He settled in the United States where he soon became involved in the Group Theatre in New York. Founded by Harold Clurman, Cheryl Crawford and Lee Strasberg, the Group was a pioneering attempt to create a theatre collective, a company of players trained in a unified style and dedicated to presenting contemporary plays. Others involved in the group included Elia Kazan, Stella Adler, John Garfield, Luther Adler, Will Geer, Howard Da Silva, Franchot Tone, John Randolph, Joseph Bromberg, Michael Gordon, Paul Green, Clifford Odets and Lee J. Cobb. Members of the group tended to hold left-wing political views and wanted to produce plays that dealt with important social issues.

In 1936 Harold Clurman and Cheryl Crawford of the Group Theatre commissioned Weill to write the music for Johnny Johnson, an anti-war play written by Paul Green. Over the next few years Weill wrote the music for several theatre productions including Lady in the Dark (1940), Street Scene (1946) and Lost in the Stars (1949).

Weill wrote the music for several Hollywood films including You and Me (1938), Blockade (1938), Knickerbocker Holiday (1944), Lady in the Dark (1944), Where Do We Go From Here (1945), Salute to France (1946) and One Touch of Venus (1948).

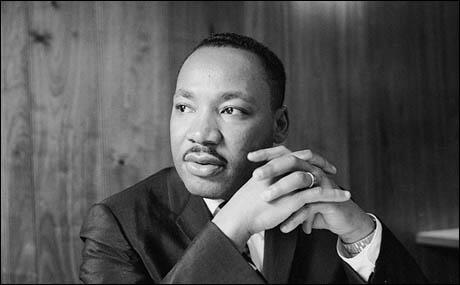

On this day in 1968 Martin Luther King makes his famous I've Been to the Mountaintop speech. In March 1968, King agreed to visit Memphis, Tennessee, in support of a strike by the city's sanitation workers.The following day, King was killed by a sniper's bullet while standing on the balcony of the motel where he was staying.

Thank you very kindly, my friends. As I listened to Ralph Abernathy in his eloquent and generous introduction and then thought about myself, I wondered who he was talking about. It’s always good to have your closest friend and associate to say something good about you, and Ralph Abernathy is the best friend that I have in the world.

I’m delighted to see each of you here tonight in spite of a storm warning. You reveal that you are determined to go on anyhow. Something is happening in Memphis, something is happening in our world. And you know, if I were standing at the beginning of time with the possibility of taking a kind of general and panoramic view of the whole of human history up to now, and the Almighty said to me, "Martin Luther King, which age would you like to live in?" I would take my mental flight by Egypt, and I would watch God’s children in their magnificent trek from the dark dungeons of Egypt through, or rather, across the Red Sea, through the wilderness, on toward the promised land. And in spite of its magnificence, I wouldn’t stop there.

I would move on by Greece, and take my mind to Mount Olympus. And I would see Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Euripides, and Aristophenes assembled around the Parthenon, and I would watch them around the Parthenon as they discussed the great and eternal issues of reality. But I wouldn’t stop there.

I would go on even to the great heyday of the Roman Empire, and I would see developments around there, through various emperors and leaders. But I wouldn’t stop there.

I would even come up to the day of the Renaissance and get a quick picture of all that the Renaissance did for the cultural and aesthetic life of man. But I wouldn’t stop there.

I would even go by the way that the man for whom I’m named had his habitat, and I would watch Martin Luther as he tacks his ninety-five theses on the door at the church of Wittenberg. But I wouldn’t stop there.

I would come on up even to 1863 and watch a vacillating president by the name of Abraham Lincoln finally come to the conclusion that he had to sign the Emancipation Proclamation. But I wouldn’t stop there.

I would even come up to the early thirties and see a man grappling with the problems of the bankruptcy of his nation, and come with an eloquent cry that "we have nothing to fear but fear itself." But I wouldn’t stop there.

Strangely enough, I would turn to the Almighty and say, "If you allow me to live just a few years in the second half of the twentieth century, I will be happy."

Now that’s a strange statement to make because the world is all messed up. The nation is sick, trouble is in the land, confusion all around. That’s a strange statement. But I know, somehow, that only when it is dark enough can you see the stars. And I see God working in this period of the twentieth century in a way that men in some strange way are responding. Something is happening in our world. The masses of people are rising up. And wherever they are assembled today, whether they are in Johannesburg, South Africa; Nairobi, Kenya; Accra, Ghana; New York City; Atlanta, Georgia; Jackson, Mississippi; or Memphis, Tennessee, the cry is always the same: "We want to be free."

And another reason that I’m happy to live in this period is that we have been forced to a point where we are going to have to grapple with the problems that men have been trying to grapple with through history, but the demands didn’t force them to do it. Survival demands that we grapple with them. Men for years now have been talking about war and peace. But now, no longer can they just talk about it. It is no longer a choice between violence and nonviolence in this world; it’s nonviolence or nonexistence. That is where we are today.

And also, in the human rights revolution, if something isn’t done and done in a hurry to bring the colored peoples of the world out of their long years of poverty, their long years of hurt and neglect, the whole world is doomed. Now, I’m just happy that God has allowed me to live in this period, to see what is unfolding. And I’m happy that he’s allowed me to be in Memphis.

I can remember, I can remember when Negroes were just going around, as Ralph has said so often, scratching where they didn’t itch and laughing when they were not tickled. But that day is all over. We mean business now and we are determined to gain our rightful place in God’s world. And that’s all this whole thing is about. We aren’t engaged in any negative protest and in any negative arguments with anybody. We are saying that we are determined to be men. We are determined to be people. We are saying, we are saying that we are God’s children. And if we are God’s children, we don’t have to live like we are forced to live.

Now, what does all of this mean in this great period of history? It means that we’ve got to stay together. We’ve got to stay together and maintain unity. You know, whenever Pharaoh wanted to prolong the period of slavery in Egypt, he had a favorite formula for doing it. What was that? He kept the slaves fighting among themselves. But whenever the slaves get together, something happens in Pharaoh’s court, and he cannot hold the slaves in slavery. When the slaves get together, that’s the beginning of getting out of slavery. Now let us maintain unity.

Secondly, let us keep the issues where they are. The issue is injustice. The issue is the refusal of Memphis to be fair and honest in its dealings with its public servants, who happen to be sanitation workers. Now, we’ve got to keep attention on that. That’s always the problem with a little violence. You know what happened the other day, and the press dealt only with the window breaking. I read the articles. They very seldom got around to mentioning the fact that one thousand three hundred sanitation workers are on strike, and that Memphis is not being fair to them, and that Mayor Loeb is in dire need of a doctor. They didn’t get around to that.

Now we’re going to march again, and we’ve got to march again , in order to put the issue where it is supposed to be and force everybody to see that there are thirteen hundred of God’s children here suffering, sometimes going hungry, going through dark and dreary nights wondering how this thing is going to come out. That’s the issue. And we’ve got to say to the nation, we know how it’s coming out. For when people get caught up with that which is right and they are willing to sacrifice for it, there is no stopping point short of victory.

We aren’t going to let any mace stop us. We are masters in our nonviolent movement in disarming police forces; they don’t know what to do. I’ve seen them so often. I remember in Birmingham, Alabama, when we were in that majestic struggle there, we would move out of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church day after day. By the hundreds we would move out, and Bull Connor would tell them to send the dogs forth, and they did come. But we just went before the dogs singing, "Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around." Bull Connor next would say, "Turn the fire hoses on." And as I said to you the other night, Bull Connor didn’t know history. He knew a kind of physics that somehow didn’t relate to the trans-physics that we knew about. And that was the fact that there was a certain kind of fire that no water could put out. And we went before the fire hoses. We had known water. If we were Baptist or some other denominations, we had been immersed. If we were Methodist and some others, we had been sprinkled. But we knew water. That couldn’t stop us.

And we just went on before the dogs and we would look at them, and we’d go on before the water hoses and we would look at it. And we’d just go on singing, "Over my head, I see freedom in the air."And then we would be thrown in the paddy wagons, and sometimes we were stacked in there like sardines in a can. And they would throw us in, and old Bull would say, "Take ’em off." And they did, and we would just go on in the paddy wagon singing, "We Shall Overcome." And every now and then we’d get in jail, and we’d see the jailers looking through the windows being moved by our prayers and being moved by our words and our songs. And there was a power there which Bull Connor couldn’t adjust to, and so we ended up transforming Bull into a steer, and we won our struggle in Birmingham.

Now we’ve got to go on in Memphis just like that. I call upon you to be with us when we go out Monday. Now about injunctions. We have an injunction and we’re going into court tomorrow morning to fight this illegal, unconstitutional injunction. All we say to America is be true to what you said on paper. If I lived in China or even Russia, or any totalitarian country, maybe I could understand some of these illegal injunctions. Maybe I could understand the denial of certain basic First Amendment privileges, because they haven’t committed themselves to that over there. But somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech. Somewhere I read of the freedom of press. Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for rights. And so just as I say we aren’t going to let any dogs or water hoses turn us around, we aren’t going to let any injunction turn us around. We are going on. We need all of you.

You know what’s beautiful to me is to see all of these ministers of the Gospel. It’s a marvelous picture. Who is it that is supposed to articulate the longings and aspirations of the people more than the preacher? Somehow the preacher must have a kind of fire shut up in his bones, and whenever injustice is around he must tell it. Somehow the preacher must be an Amos, who said, "When God speaks, who can but prophesy?" gain with Amos, "Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream." Somehow the preacher must say with Jesus, "The spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me, and he has anointed me to deal with the problems of the poor."

And I want to commend the preachers, under the leadership of these noble men: James Lawson, one who has been in this struggle for many years. He’s been to jail for struggling; he’s been kicked out of Vanderbilt University for this struggling; but he’s still going on, fighting for the rights of his people. Reverend Ralph Jackson, Billy Kiles; I could just go right down the list, but time will not permit. But I want to thank all of them, and I want you to thank them, because so often preachers aren’t concerned about anything but themselves.

And I’m always happy to see a relevant ministry. It’s all right to talk about long white robes over yonder, in all of its symbolism, but ultimately people want some suits and dresses and shoes to wear down here. It’s all right to talk about streets flowing with milk and honey, but God has commanded us to be concerned about the slums down here and his children who can’t eat three square meals a day. It’s all right to talk about the new Jerusalem, but one day God’s preacher must talk about the new New York, the new Atlanta, the new Philadelphia, the new Los Angeles, the new Memphis, Tennessee. This is what we have to do.

Now the other thing we’ll have to do is this: always anchor our external direct action with the power of economic withdrawal. Now we are poor people individually, we are poor when you compare us with white society in America. We are poor. But never stop and forget that collectively, that means all of us together, collectively we are richer than all the nations in the world, with the exception of nine. Did you ever think about that? After you leave the United States, Soviet Russia, Great Britain, West Germany, France, and I could name the others, the American Negro collectively is richer than most nations of the world. We have an annual income of more than thirty billion dollars a year, which is more than all of the exports of the United States and more than the national budget of Canada. Did you know that? That’s power right here, if we know how to pool it.

We don’t have to argue with anybody. We don’t have to curse and go around acting bad with our words. We don’t need any bricks and bottles; we don’t need any Molotov cocktails. We just need to go around to these stores, and to these massive industries in our country , and say, "God sent us by here to say to you that you’re not treating his children right. And we’ve come by here to ask you to make the first item on your agenda fair treatment where God’s children are concerned. Now, if you are not prepared to do that, we do have an agenda that we must follow. And our agenda calls for withdrawing economic support from you."

And so, as a result of this, we are asking you tonight to go out and tell your neighbors not to buy Coca-Cola in Memphis. Go by and tell them not to buy Sealtest milk. Tell them not to buy - what is the other bread? - Wonder Bread. And what is the other bread company, Jesse? Tell them not to buy Hart’s bread. As Jesse Jackson has said, up to now only the garbage men have been feeling pain, now we must kind of redistribute the pain. We are choosing these companies because they haven’t been fair in their hiring policies, and we are choosing them because they can begin the process of saying they are going to support the needs and the rights of these men who are on strike. And then they can move on downtown and tell Mayor Loeb to do what is right.

Now not only that, we’ve got to strengthen black institutions. I call upon you to take your money out of the banks downtown and deposit your money in Tri-State Bank. We want a "bank-in" movement in Memphis. Go by the savings and loan association. I’m not asking you something that we don’t do ourselves in SCLC. Judge Hooks and others will tell you that we have an account here in the savings and loan association from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. We are telling you to follow what we’re doing, put your money there. You have six or seven black insurance companies here in the city of Memphis. Take out your insurance there. We want to have an "insurance-in." Now these are some practical things that we can do. We begin the process of building a greater economic base. And at the same time, we are putting pressure where it really hurts, and I ask you to follow through here.

Now let me say as I move to my conclusion that we’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through. When we have our march, you need to be there. If it means leaving work, if it means leaving school, be there. Be concerned about your brother. You may not be on strike, but either we go up together or we go down together. Let us develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness.

One day a man came to Jesus and he wanted to raise some questions about some vital matters of life. At points he wanted to trick Jesus, and show him that he knew a little more than Jesus knew and throw him off base. Now that question could have easily ended up in a philosophical and theological debate. But Jesus immediately pulled that question from mid-air and placed it on a dangerous curve between Jerusalem and Jericho. And he talked about a certain man who fell among thieves. You remember that a Levite and a priest passed by on the other side; they didn’t stop to help him. Finally, a man of another race came by. He got down from his beast, decided not to be compassionate by proxy. But he got down with him, administered first aid, and helped the man in need. Jesus ended up saying this was the good man, this was the great man, because he had the capacity to project the "I" into the "thou," and to be concerned about his brother.

Now you know, we use our imagination a great deal to try to determine why the priest and the Levite didn’t stop. At times we say they were busy going to a church meeting, an ecclesiastical gathering, and they had to get on down to Jerusalem so they wouldn’t be late for their meeting. At other times we would speculate that there was a religious law that one who was engaged in religious ceremonials was not to touch a human body twenty-four hours before the ceremony. And every now and then we begin to wonder whether maybe they were not going down to Jerusalem, or down to Jericho, rather, to organize a Jericho Road Improvement Association. That’s a possibility. Maybe they felt that it was better to deal with the problem from the causal root, rather than to get bogged down with an individual effect.

But I’m going to tell you what my imagination tells me. It’s possible that those men were afraid. You see, the Jericho Road is a dangerous road. I remember when Mrs. King and I were first in Jerusalem. We rented a car and drove from Jerusalem down to Jericho. And as soon as we got on that road I said to my wife, "I can see why Jesus used this as the setting for his parable." It’s a winding, meandering road. It’s really conducive for ambushing. You start out in Jerusalem, which is about 1200 miles, or rather, 1200 feet above sea level. And by the time you get down to Jericho fifteen or twenty minutes later, you’re about 2200 feet below sea level. That’s a dangerous road. In the days of Jesus it came to be known as the "Bloody Pass." And you know, it’s possible that the priest and the Levite looked over that man on the ground and wondered if the robbers were still around. Or it’s possible that they felt that the man on the ground was merely faking. And he was acting like he had been robbed and hurt, in order to seize them over there, lure them there for quick and easy seizure. And so the first question that the priest asked, the first question that the Levite asked was, "If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?"

But then the Good Samaritan came by, and he reversed the question: "If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?" That’s the question before you tonight. Not, "If I stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to my job?" Not, "If I stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to all of the hours that I usually spend in my office every day and every week as a pastor?" The question is not, "If I stop to help this man in need, what will happen to me?" The question is, "If I do not stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to them?" That’s the question.

Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with a greater determination. And let us move on in these powerful days, these days of challenge, to make America what it ought to be. We have an opportunity to make America a better nation.

And I want to thank God, once more, for allowing me to be here with you. You know, several years ago I was in New York City autographing the first book that I had written. And while sitting there autographing books, a demented black woman came up. The only question I heard from her was, "Are you Martin Luther King?" And I was looking down writing and I said, "Yes."

The next minute I felt something beating on my chest. Before I knew it I had been stabbed by this demented woman. I was rushed to Harlem Hospital. It was a dark Saturday afternoon. And that blade had gone through, and the X-rays revealed that the tip of the blade was on the edge of my aorta, the main artery. And once that’s punctured you’re drowned in your own blood; that’s the end of you. It came out in The New York Times the next morning that if I had merely sneezed, I would have died.

Well, about four days later, they allowed me, after the operation, after my chest had been opened and the blade had been taken out, to move around in the wheelchair in the hospital. They allowed me to read some of the mail that came in, and from all over the states and the world kind letters came in. I read a few, but one of them I will never forget. I had received one from the president and the vice-president; I’ve forgotten what those telegrams said. I’d received a visit and a letter from the governor of New York, but I’ve forgotten what that letter said.

But there was another letter that came from a little girl, a young girl who was a student at the White Plains High School. And I looked at the letter and I’ll never forget it. It said simply, "Dear Dr. King: I am a ninth-grade student at the White Plains High School." She said, "While it should not matter, I would like to mention that I’m a white girl. I read in the paper of your misfortune and of your suffering. And I read that if you had sneezed, you would have died. And I’m simply writing you to say that I’m so happy that you didn’t sneeze."

And I want to say tonight, I want to say tonight that I, too, am happy that I didn’t sneeze. Because if I had sneezed , I wouldn’t have been around here in 1960, when students all over the South started sitting-in at lunch counters. And I knew that as they are sitting in, they were really standing up for the best in the American dream and taking the whole nation back to those great wells of democracy, which were dug deep by the founding fathers in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been around here in 1961, when we decided to take a ride for freedom and ended segregation in interstate travel.

If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been around here in 1962, when Negroes in Albany, Georgia, decided to straighten their backs up. And whenever men and women straighten their backs up, they are going somewhere, because a man can’t ride your back unless it is bent.

If I had sneezed, if I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been here in 1963, when the black people of Birmingham, Alabama, aroused the conscience of this nation and brought into being the civil rights bill.

If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have had a chance later that year, in August, to try to tell America about a dream that I had had.

If I had sneezed,I wouldn’t have been down in Selma, Alabama, to see the great movement there.

If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been in Memphis to see a community rally around those brothers and sisters who are suffering. I’m so happy that I didn’t sneeze.

And they were telling me. Now it doesn’t matter now . It really doesn’t matter what happens now. I left Atlanta this morning, and as we got started on the plane - there were six of us - the pilot said over the public address system, "We are sorry for the delay, but we have Dr. Martin Luther King on the plane. And to be sure that all of the bags were checked and to be sure that nothing would be wrong on the plane, we had to check out everything carefully. And we’ve had the plane protected and guarded all night."

And then I got into Memphis. And some began to say the threats, or talk about the threats that were out, or what would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers.

Well, I don’t know what will happen now; we’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life - longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight , that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. So I’m happy tonight; I’m not worried about anything; I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

On this day in 1971 Clara Codd died at Heatherwood Hospital, Sunninghill, Berkshire, of heart failure.