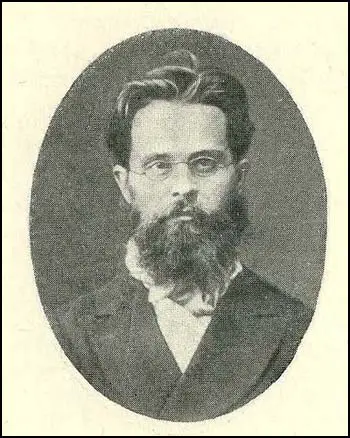

Nikolai Morozov

Nikolai Morozov, the illegitimate son of a landowner near Yaroslavl, was born on 7th July, 1854. His interest in politics started early and he was expelled from secondary school when he was accused of subversive activity.

In 1874 he moved to Zurich where he joined up with a group of radical students that included Vera Figner, Lydia Figner, Olga Liubatovich, and Sophia Bardina. Liubatovich later described meeting Morozov for the first time: "Morozov blushed like a girl. Apart from his literary work, he was one of the party's most ardent advocates of partisan revolutionary warfare - terrorist struggle - and he was always heavily laden with guns, nearly bent over from their weight. He was above average in height, with large, pensive eyes and very delicate, miniature features. His body, thin and frail, seemed underdeveloped, and his weak, high-pitched voice reinforced my image of him as a sapling that had grown up far from fresh air and open fields."

In 1876 Morozov helped to form the Land and Liberty secret society. Most of the group followed the anarchist teachings of Mikhail Bakunin and demanded that Russia's land should be handed over to the peasants and the State should be destroyed. Morozov co-edited the journal Land and Liberty with Sergei Kravchinsky. The historian, Adam Bruno Ulam, has argued: "This Party, which commemorated in its name the revolutionary grouping of the early sixties, was soon split up by quarrels about its attitude toward terror. The professed aim, the continued agitation among the peasants, grew more and more fruitless."

In October, 1879, the Land and Liberty split into two factions. The majority of members, who favoured a policy of terrorism, established the People's Will (Narodnaya Volya). Others, such as George Plekhanov formed Black Repartition, a group that rejected terrorism and supported a socialist propaganda campaign among workers and peasants. Elizabeth Kovalskaia was one of those who rejected the ideas of the People's Will: "Firmly convinced that only the people themselves could carry out a socialist revolution and that terror directed at the centre of the state (such as the People's Will advocated) would bring - at best - only a wishy-washy constitution which would in turn strengthen the Russian bourgeoisie, I joined Black Repartition, which had retained the old Land and Liberty program."

Morozov, Vera Figner, Anna Korba, Andrei Zhelyabov, Olga Liubatovich, Nikolai Morozov, Timofei Mikhailov, Lev Tikhomirov, Mikhail Frolenko, Grigory Isaev, Sophia Perovskaya, Nikolai Sablin, Ignatei Grinevitski, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov, Gesia Gelfman, Anna Yakimova, Sergei Kravchinskii, Tatiana Lebedeva and Alexander Kviatkovsky all joined the People's Will. Figner later recalled: "We divided up the printing plant and the funds - which were in fact mostly in the form of mere promises and hopes... And as our primary aim was to substitute the will of the people for the will of one individual, we chose the name Narodnaya Volya for the new Party."

Michael Burleigh, the author of Blood & Rage: A Cultural History of Terrorism (2008), has argued that the main influence on this small group was Sergi Nechayev: "The terrorist nucleus of Land and Freedom had already adopted many of Nechayev's dubious practices, including bank robberies and murdering informers. People's Will also borrowed his tactic of suggesting to the credulous that it was the tip of a much larger revolutionary organisation - the Russian Social Revolutionary Party - which in reality was non-existent. There was an imposing-sounding Executive Committee all right, but this was coterminous with the entire membership of People's Will... In fact, People's Will never had more than thirty or forty members, who would then recruit agents for specific tasks or to establish affiliate cells within sections of society deemed to have revolutionary potential."

Soon afterwards the People's Will decided to assassinate Alexander II. A directive committee was formed consisting of Andrei Zhelyabov, Timofei Mikhailov, Lev Tikhomirov, Mikhail Frolenko, Vera Figner, Sophia Perovskaya and Anna Yakimova. Zhelyabov was considered the leader of the group. However, Figner considered him to be overbearing and lacking in depth: "He had not suffered enough. For him all was hope and light." Zhelyabov had a magnetic personality and had a reputation for exerting a strong influence over women.

Zhelyabov and Perovskaya attempted to use nitroglycerine to destroy the Tsar train. However, the terrorist miscalculated and it destroyed another train instead. An attempt the blow up the Kamenny Bridge in St. Petersburg as the Tsar was passing over it was also unsuccessful. Figner blamed Zhelyabov for these failures but others in the group felt he had been unlucky rather than incompetent.

In 1880 there was strong disagreement in People's Will about the purposes of terrorism. One group that included Morozov and his wife, Olga Liubatovich, argued that the main objective was to force the government to grant democratic rights to the people of Russia. However, another faction, led by Lev Tikhomirov, who had been deeply influenced by the ideas of Sergi Nechayev, believed that it was possible for a small group of revolutionaries to gain control and then hand over its powers to the people.

Liubatovich later argued: "During the debates, the question of Jacobinism - seizing power and ruling from above, by decree - was raised. As I saw it, the Jacobin tinge that Tikhomirov gave to his program for the Executive Committee gave to his program for the Executive Committee threatened the party and the entire revolutionary movement with moral death; it was a kind of rebirth of Nechaevism, which had long since lost moral credit in the revolutionary world. It was my belief that the revolutionary idea could be a life-giving force only when it was the antithesis of all coercion - social, state, and even personal coercion, tsarist and Jacobin alike. Of course, it was possible for a narrow group of ambitious men to replace one form of coercion or authority by another. But neither the people nor educated society would follow them consciously, and only a conscious movement can impart new principles to public life."

Morozov agreed with Liubatovich: "At this point, Morozov announced that he considered himself free of any obligation to defend a program like Tikhomirov's in public. I too, declared that it was against my nature to act on the basis of compulsion; that once the Executive Committee had taken on a task - the seizure of state power - that violated my basic principles, and once it had recourse in its organizational practice to autocratic methods fraught with mutual distrust, then I, too, reclaimed my freedom of action."

In the summer of 1880 Liubatovich and Morozov left the People's Will and went to live in Geneva. While in exile Morozov wrote The Terrorist Struggle, a pamphlet that explained his views on how to achieve a democratic society in Russia. Based on ideas developed with Liubatovich, Morozov advocated the creation of a large number of small, independent terrorist groups. He argued that this approach would make it more difficult for the police to apprehend the terrorists. It would also help to prevent a small group of leaders gaining dictatorial powers after the overthrow of the Tsar.

Morozov returned to Russia in order to distribute the pamphlet. He was soon arrested and imprisoned in Suvalki. Liubatovich, who had recently given birth to their child, decided to try and rescue him. She later wrote: "By early morning, I was at Kravchinsky's. Sergei was remarkably thoughtful: he had already obtained a crib for my little girl and set it up in a clean, light room. He left me alone with the child. For a long time I stood like a statue in the middle of the room, the tired baby sleeping in my arms. Her face, pink from sleep, was peaceful and filled with the beauty of childhood. When I finally decided to lower her into the bed, she opened her eyes - large, serious, peaceful, still enveloped in sleep. I couldn't bear her gaze. Not daring to kiss her lest I wake her up. I quietly walked out of the room. I thought I'd be back; I didn't know, didn't want to believe that I was seeing my little girl for the last time. My heart was numb with grief."

Morozov was imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress and in Shlisselburg Castle. During this period he studied physics, chemistry, astronomy and history. He remained in captivity until the political amnesty that followed the 1905 Revolution. On his release he taught chemistry and astronomy at the university of St. Petersburg. In 1907 he was elected into the Duma. In 1910 he upset the authorities with his book, Songs of the Stars, and was imprisoned for another year.

Nikolai Morozov died on 30th July, 1946.

Primary Sources

(1) Olga Liubatovich first met Nikolai Morozov in 1876.

Sergei Kravchinskii came by with his close friend Nikolai Morozov, whom he introduced as "our young poet". Morozov blushed like a girl. Apart from his literary work, he was one of the party's most ardent advocates of partisan revolutionary warfare - terrorist struggle - and he was always heavily laden with guns, nearly bent over from their weight.

He was above average in height, with large, pensive eyes and very delicate, miniature features. His body, thin and frail, seemed underdeveloped, and his weak, high-pitched voice reinforced my image of him as a sapling that had grown up far from fresh air and open fields. He seemed very young to me, and unwittingly I adopted an almost patronizing manner. Strangely enough, this made us feel closer to each other.

Morozov had repudiated without regret the privileges that lesser people cling so tenaciously. Clothing himself in a course caftan and bark shoes, he travelled over nearly all of Great Russia, talking with the people and distributing revolutionary pamphlets. Inexperienced and impetuous, he ignored all precautions; he was eventually seized and turned over to the authorities by the peasants themselves.

(2) Nikolai Morozov and Olga Liubatovich left the People's Will over the issue of Jacobinism in 1880.

During the debates, the question of Jacobinism - seizing power and ruling from above, by decree - was raised. As I saw it, the Jacobin tinge that Tikhomirov gave to his program for the Executive Committee gave to his program for the Executive Committee threatened the party and the entire revolutionary movement with moral death; it was a kind of rebirth of Nechaevism, which had long since lost moral credit in the revolutionary world. It was my belief that the revolutionary idea could be a life-giving force only when it was the antithesis of all coercion - social, state, and even personal coercion, tsarist and Jacobin alike. Of course, it was possible for a narrow group of ambitious men to replace one form of coercion or authority by another. But neither the people nor educated society would follow them consciously, and only a conscious movement can impart new principles to public life.

At this point, Morozov announced that he considered himself free of any obligation to defend a program like Tikhomirov's in public. I too, declared that it was against my nature to act on the basis of compulsion; that once the Executive Committee had taken on a task - the seizure of state power - that violated my basic principles, and once it had recourse in its organizational practice to autocratic methods fraught with mutual distrust, then I, too, reclaimed my freedom of action.

(3) After the arrest of Nikolai Morozov in 1881, Olga Liubatovich returned to Russia to try and help him escape from prison. This meant that she had to leave their young baby behind with friends. The baby died of meningitis when it was six months old.

By early morning, I was at Kravchinskii's. Sergei was remarkably thoughtful: he had already obtained a crib for my little girl and set it up in a clean, light room. He left me alone with the child. For a long time I stood like a statue in the middle of the room, the tired baby sleeping in my arms. Her face, pink from sleep, was peaceful and filled with the beauty of childhood. When I finally decided to lower her into the bed, she opened her eyes - large, serious, peaceful, still enveloped in sleep. I couldn't bear her gaze. Not daring to kiss her lest I wake her up. I quietly walked out of the room. I thought I'd be back; I didn't know, didn't want to believe that I was seeing my little girl for the last time. My heart was numb with grief.